59 Renal Neoplasms

Etiology and Pathogenesis

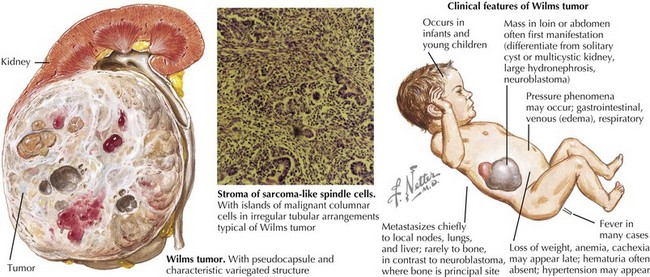

Wilms’ Tumor

Wilms’ tumor accounts for the majority (85%) of pediatric renal tumors with 500 new cases per year in the United States (Figure 59-1). The more aggressive anaplastic histologic subtype of Wilms’ makes up about 8% of all pediatric renal tumors. The mean age at presentation is 3 to 4 years for unilateral disease, and the majority of patients are younger than 10 years old at diagnosis. Patients with bilateral disease account for 5% of all Wilms’ cases and present younger than those for unilateral disease at 2 to 2.5 years of age.

Clinical Presentation

Evaluation and Management

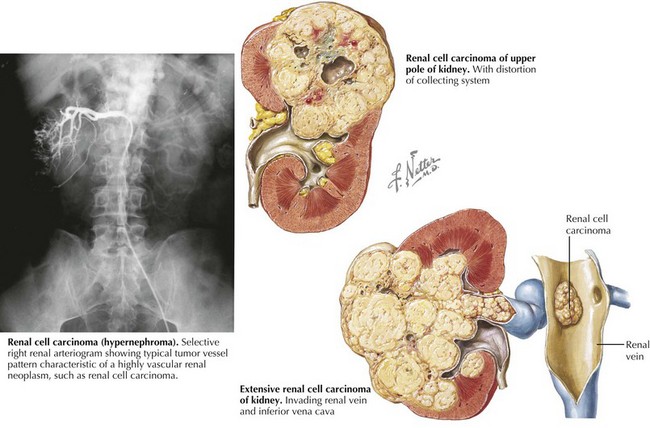

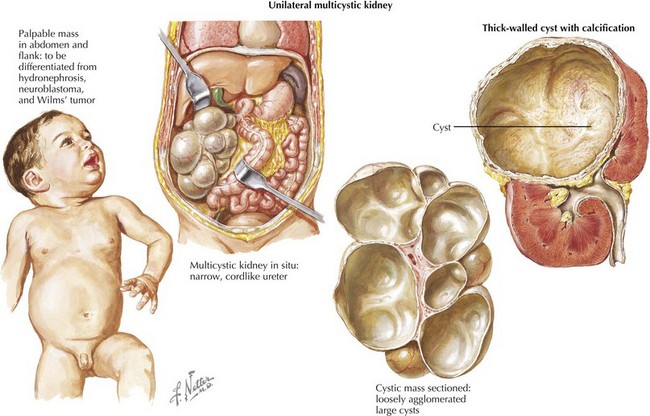

Radiologic evaluation usually begins with abdominal ultrasonography to help determine the site of origin and whether the mass is cystic or solid. If a tumor arising from the kidney is identified, higher resolution imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended as well as imaging evaluation for metastatic disease (see for specific tumors below). Because of the propensity for Wilms’ tumor and other more aggressive renal tumors to spread into the renal vessels and extend into the inferior vena cava (often into the right atrium, deemed “tumor thrombus”), it is essential to image the renal and large vessels with Doppler to assess extent of venous obstruction. Vascular invasion of tumor can affect the surgical approach, staging, and management decisions (Figure 59-2).The differential diagnosis for a patient with a renal mass is given in Box 59-1. One element of the differential diagnosis is shown in Figure 59-3 .

Tumor-Specific Evaluations and Management

Argani P, Perlman EJ, Breslow NE, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney: a review of 351 cases from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group Pathology Center. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:4-18.

Beckwith JB. Nephrogenic rests and the pathogenesis of Wilms tumor: developmental and clinical considerations. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:268-273.

Bernstein L, Linet M, Smith MA, Olshan AF, the National Cancer Institute. Renal Tumors. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/publications/childhood/renal.pdf

Dome JS, Perlman EJ, Ritchey ML, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. ed 5. Philadelphia, Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2006:905-932.

Geller JI, Dome JS. Local lymph node involvement does not predict poor outcome in pediatric renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:1575-1583.

Hartman DJ, MacLennan GT. Wilms tumor. J Urol. 2005;173:2147.

Huff V. Wilms tumor genetics: a new, UnX-pected twist to the story. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:105-107.

Kaste SC, Dome JS, Babyn PS, et al. Wilms tumor: prognostic factors, staging, therapy and late effects. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:2-17.

Lowe LH, Isuani BH, Heller RM, et al. Pediatric renal masses: Wilms tumor and beyond. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1585-1603.

Perlman EJ, Faria P, Soares A, et al. Hyperplastic perilobar nephroblastomatosis: long-term survival of 52 patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46:203-221.