Chapter 35 Renal disease

Introduction

Chronic Kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease has increased in prevalence in the US by 20–25% from the 1988–1994 period of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey1, 2 and affects an estimated 31 million people in that country.1

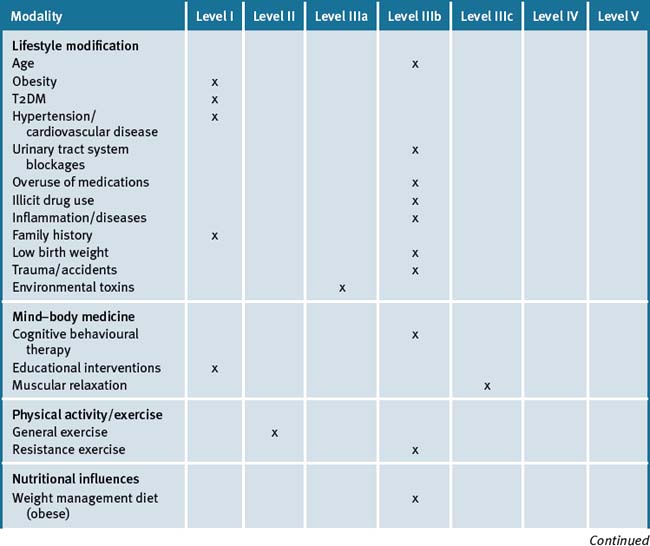

Kidney disease is defined as any one of several chronic conditions that are caused by damage to the cells of the kidney. It is a major cause of disease and death in the US and important causative factors have been identified (see Table 35.1).

Table 35.1 Key and other factors associated with kidney disease

| Age |

| Obesity∗ |

| Diabetes∗ |

| High blood pressure∗ |

| Heart disease∗ |

| Urinary tract system blockages |

| Medication: overuse or adverse reactions |

| Illicit drug abuse |

| Inflammation and/or disease processes |

| Family history of kidney failure∗ |

| Low birth weight |

| Trauma and/or accident |

| Environmental toxins |

Diabetes is the single leading cause of kidney failure in the US. Nephropathy is a condition that affects one-third or more of people who have had type 1 (juvenile) diabetes for at least 20 years. About 20–40% of people with type 2 (adult onset) diabetes also have kidney disease.3

A recent descriptive study from Germany has found that use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) is common among renal patients.4 This is consistent with other reports that have indicated that the consumption of complementary medicine products, including herbs, herbal teas, or nutritional supplements such as vitamins or minerals, has increased in the last decade.5

A high rate of complementary medicine product use has been documented for a number of different patient populations with chronic diseases, such as liver-transplant recipients,6 HIV-positive patients,7 patients with epilepsy,8 and patients with diabetes,9 and clinicians are often inadequately informed about CAM consumption by their patients.10

The prevalence and patterns of CAM utilisation among renal patients with chronic kidney diseases was recently investigated.11 The study revealed the following facts.

In addition, CAM products (e.g. herbal products, functional foods such as probiotics) and physical therapies (e.g. acupuncture) have been used in other non-chronic associated kidney diseases.12

Lifestyle and other risk factors

Obesity

Obesity is strongly associated with several major health risk factors.14 These include type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension and heart disease, which have significant causal correlations to chronic kidney disease.15 Moreover, studies have reported that Body Mass Index (BMI) was associated with an increased risk of the development of end-stage renal disease.16, 17

Diabetes

Approximately 40% of new incident dialysis patients have been diagnosed with diabetes which today is considered the most important and increasing risk factor for kidney disease.18, 19 T2DM (see Chapter 13 on diabetes) is the number 1 cause of kidney failure, responsible for more than 1 of every 3 new cases.18

High blood pressure (hypertension)

Hypertension is the second most common cause of kidney failure.20 High blood pressure puts more stress on blood vessels throughout the body, including the nephrons. Normal blood pressure is defined as less than 130/85 — and this is the considered target for persons diagnosed with diabetes, heart disease, or chronic kidney disease. Weight control, physical activity (see later in this chapter), and medications can control blood pressure — and can assist in preventing or slowing the progress from kidney disease to kidney failure.

Urinary tract system blockages

Scarring from infections or a malformed lower urinary tract system as a result of a birth defect can force urine backflow, damaging the kidneys.21 Blood clots or plaques of cholesterol that block the kidney’s blood vessels can reduce blood flow to the kidneys and also cause damage. Repeated kidney stones can block the flow of urine from the kidneys and is an additional cause of obstruction that can damage the kidneys.

Overuse of medications

A number of pharmaceutical drugs are known to cause renal failure as a side-effect.

Continued use of analgesic medications containing ibuprofen, naproxen, or acetaminophen have been linked to interstitial nephritis, that can lead to kidney failure.22 A US study suggested that ordinary use of analgesics (e.g. 1 pill per day) was not harmful in men who were not at risk for kidney disease.23 However, concomitant use of NSAIDs and dehydration (e.g. severe diarrhoea) can predispose to renal impairment and failure, especially in the elderly. Allergic reactions to, or side-effects of, antibiotics such as penicillin and vancomycin may also cause nephritis and lead to kidney damage.24 Note that adverse reactions can also occur with complementary medicines (CMs) (e.g. herbs and high-dose vitamins).

Illicit drug abuse

The illicit use of drugs involves millions of people worldwide and is associated with a variety of medical complications. Use of certain non-prescription drugs, such as heroin or cocaine, can damage the kidneys, and may lead to kidney failure and the need for dialysis.25, 26

Inflammation and/or diseases

Certain illnesses, like glomerulonephritis, can damage the kidneys and lead to chronic kidney disease.27 Moreover, persons at increased risk of kidney disease include those diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus, sickle cell anaemia, cancer, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, and congestive heart failure.28–32

Family history — surrogate marker for risk of future nephropathy

Persons are at an increased risk if they have 1 or more family members who have chronic kidney disease, are on dialysis, or have had a kidney transplant.33 Diabetes and high blood pressure can also have familial trends and present with risks for chronic kidney disease (see previous sections in this chapter).

Low birth weight

A recent systematic review has concluded that existing scientific data indicates that low birth weight is associated with subsequent risk of chronic kidney disease.34 Further well-designed population-based studies are required, though, in order to accurately assess birth weight and kidney function and important cofounders, such as maternal and socioeconomic factors.

Trauma and/or accident

Accidents/injuries,35 surgical procedures, and radio-contrast dyes used to monitor blood flow to the heart and other organs are a risk for developing contrast nephropathy due to reduced blood flow to the kidneys, causing acute kidney failure.36

Environmental toxins

The kidneys can be the target of numerous xenobiotic toxicants, including environmental chemicals.37 The kidney’s anatomical, physiological, and biochemical features make it particularly susceptible to many environmental compounds. Factors contributing to the sensitivity of the kidneys include: large blood flow; the presence of a variety of xenobiotic transporters and metabolising enzymes; and concentration of solutes during urine production.36

Glomerulonephritis is the most common cause of end-stage renal failure in most countries, and is exacerbated and may be causal by exposure to chemicals present in the workplace, the home and in the public environment. The most common nephrotoxic chemicals are hydrocarbons, present in organic solvents, glues, fuels, paints and motor exhausts. Exposure is common among painters, printers, cabinet makers, fitters and mechanics, electricians, and in the manufacturing industry.38, 39 Other compounds with nephro-toxicity potential include lead, mercury, cadmium and some pharmaceuticals (e.g. gentamycin).40–43

A recent study has demonstrated that contact with cadmium and lead increases the risk for chronic kidney disease.44 Given that these substances are widely distributed in populations at large, this study provides novel evidence of an increased risk with environmental exposure to both metals.

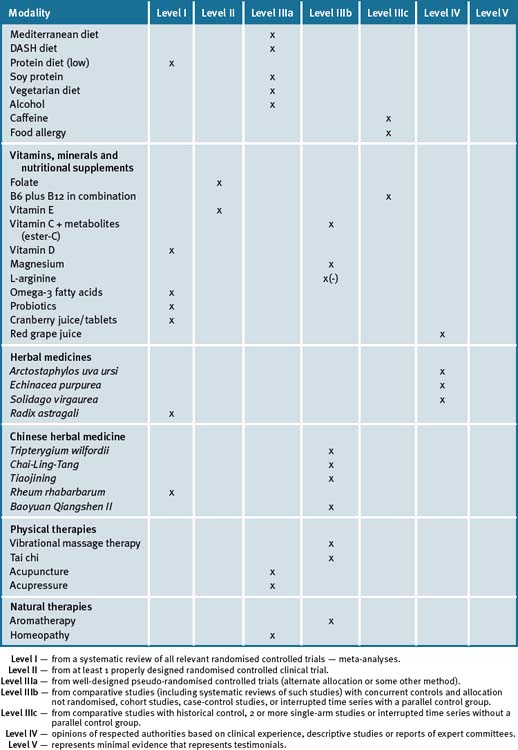

Mind–body medicine

Research shows that regular use of stress management techniques (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapies) can significantly influence those chronic disease conditions that can have adverse health effects on kidney function such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), T2DM and hypertension (see Chapters 10, 13 and 19, respectively).

Muscular relaxation

Progressive muscle relaxation training was investigated in 46 patients who had been treated with dialysis.45 The study demonstrated that progressive muscle relaxation training for dialysis patients helped decrease state- and trait-anxiety levels and had a positive impact on the QOL of these patients.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Three small trials have reported benefit with CBT for patients undergoing haemodialysis.46, 47, 48 The first study assessed the influence of CBT on chronic haemodialysis patients’ ability for self-care and to achieve fluid intake-related behavioural objectives.44

In a further study with an RCT design, enhancing adherence to haemodialysis fluid restrictions was investigated in a group of 56 participants receiving haemodialysis from 4 renal outpatient settings.46 The study showed that applying group-based CBT (4 weeks duration) was feasible and effective in enhancing adherence to haemodialysis fluid restrictions.

Another study, with a nurse-delivered haemodialysis patient education program incorporating CBT compared to a standard patient education program on patients’ salt intake and weight gain, found that both programs were shown to be effective, but CBT had a longer effect (12 weeks versus 8 weeks).47

Patients with end-stage renal disease often are diagnosed with depression49 and sleep disorders50 which have been linked to increased mortality. A recent randomised controlled pilot trial with 24 peritoneal dialysis patients reported that CBT may be effective for improving the quality of sleep and decreasing fatigue and inflammatory cytokine levels in these patients. CBT was concluded to be an effective non-pharmacological therapy for peritoneal dialysis patients with sleep disturbances.51

Educational interventions

A systematic review of randomised clinical trials was recently conducted from studies that included patients diagnosed with any of the following stages of chronic kidney disease such as early pre-dialysis and dialysis.52 Twenty-two studies were identified involving a wide range of multi-component interventions with variable aims and outcomes depending on the area of kidney disease care. Eighteen studies provided significant results for analysis. The majority of studies aimed to improve diet and/or fluid concordance in dialysis patients and involved short- and medium-term follow-up. A single major long-term study was a 20-year follow-up of a pre-dialysis educational intervention that showed increased survival rates. This review concluded that multi-component structured educational interventions were effective in pre-dialysis and dialysis care, but the quality of many studies was suboptimal.52 Further, effectively framed and developed educational interventions for implementation and evaluation are required. The study also concluded that this strategy could lead to possible prevention or delay in the progression of kidney disease.

Physical activity/exercise

Exercise can help keep people strong, flexible and better prepared to handle life stressors and illnesses.53 This is important for patients with kidney disease because, for example, independent of the course of kidney disease, physical fitness decreases continuously with the progression of chronic renal disease.54 Hence, people with kidney disease, both early and late stage, can benefit from participation in appropriate physical activity programs55 given that life expectancy in haemodialysis patients is reduced fourfold on average versus healthy age-matched individuals.56

End-stage renal disease patients present many cardiovascular complications and suffer from impaired exercise capacity. A number of studies have investigated exercise programs for patients with renal disease and found beneficial morphological, functional and psychosocial effects in end-stage renal disease patients on haemodialysis.57, 58, 59

One study noted that intense exercise training improved left ventricular systolic function at rest in haemodialysis patients. Moreover, it was reported that both intense and moderate physical training led to enhanced cardiac performance during supine sub-maximal exercise.55 An additional study compared the effects of 3 modes of exercise training on aerobic capacity and aimed to identify the most favourable, efficient and preferable to patients on haemodialysis with regard to functional improvements and participation rate in the programs.56 Fifty-eight volunteer participants were screened for low-risk status and selected from the dialysis population. The 48 patients who completed the study protocol were randomly assigned either to 1 of the 3 training groups or to a control group. These results showed that intense exercise training on non-dialysis days was the most effective way of training, whereas exercise during haemodialysis was also effective and preferable.56 An additional study by the same research group showed that haemodialysis patients can adhere to long-term physical training programs on the non-dialysis days, as well as during haemodialysis, with considerable improvements in physical fitness and health. Also, although training out of haemodialysis seemed to result in better outcomes, the dropout rate was higher.57

A more recent study investigated a total of 50 patients with chronic kidney disease (stage 5) on haemodialysis and 35 healthy individuals who served as controls. The 50 chronic kidney disease patients were divided into 2 groups — the haemodialysis group consisted of 31 patients who received usual care without any physical activity during the haemodialysis sessions, while the haemodialysis/physical activity group included 19 patients who followed a program of physical exercise for 6 months.60 The study established that exercise training during haemodialysis exerted a beneficial effect on the levels of the vasoactive eicosanoid hormone-like substances in patients on haemodialysis.60

A recent single centre prospective study whose objective was to examine the relationship between visceral and somatic protein stores and physical activity in individuals with end-stage renal disease showed that the association between somatic protein and visceral protein stores is weak in patients with chronic kidney disease. Whereas increased levels of physical activity and total daily protein intake were associated with higher lean body mass in patients with chronic kidney disease, higher adiposity was associated with higher C-reactive protein and lower albumin values.61

Furthermore, an additional study with the objective of determining whether 24 weeks resistance training during haemodialysis could improve exercise capacity, muscle strength, physical functioning and health-related QOL compared to a low-intensity aerobic program was investigated in 27 patients recruited from 2 haemodialysis clinics.62 It was concluded that resistance training during haemodialysis significantly improved patient’s physical functioning.

A recent review presented empirical evidence that intradialytic exercise can mitigate primary independent risk factors for early mortality in end-stage renal disease, hence, reducing the progression of skeletal muscle wasting, improving systemic inflammation, cardiovascular function and dialysis adequacy.63 The review concludes that intradialytic cycling and/or progressive resistance training can alleviate primary independent risk factors for early mortality in end-stage renal disease.

Clinical trials have further supported the benefits gained with resistance training exercise by end-stage renal disease patients on haemodialysis.64, 65 The first study which was a single-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of an exercise intervention in haemodialysis patients administered erythropoietin. The intervention consisted of progressive resisted isotonic quadriceps and hamstrings exercises and training on a cycle ergometer 3 times weekly for 12 weeks. The results showed that the exercise program improved physical impairment measures, but had no effect on symptoms or health-related QOL.62 The second randomised study was designed to determine whether anabolic steroid administration and resistance exercise training combined induced anabolic effects among patients who were receiving maintenance haemodialysis.63 This study found that patients who exercised increased their strength in a training-specific fashion, and exercise was associated with a significant improvement in self-reported physical functioning as compared with non-exercising groups. Nandrolone decanoate and resistance exercise combined produced anabolic effects among patients who were on haemodialysis.

Moreover it should be noted that as of 2008 there have been over 50 reports, including several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that have evaluated the effects of intradialytic exercise in end-stage kidney disease.61

Nutritional influences

Diets and nutritional practices have significant multiple health-related risk factors with ramifications that, if prolonged, can lead to kidney disease.66 An example of such a multiple health-related risk factor is obesity and its related risks (see Chapters 10, cardiovascular disease; 13, diabetes; and 19, hypertension).

Weight loss management of obese patients is crucial.14, 15, 16

Mediterranean diet

Traditional diets among Mediterranean cultures (Mediterranean diet) are characterised by the abundance of natural whole foods, especially fruits and vegetables, along with olive oil, fish, and nuts. The diet includes moderate amounts of wine and is low in saturated fat.67

A study reported that adhering to a Mediterranean diet provides for a healthier and nutritional hypolipidemic approach in renal transplant recipients.68 This study reported that this diet led to a significant reduction in total cholesterol levels by 10%, triglycerides by 6.5%, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-cholesterol) by 10.4% and the ratio of LDL-cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol) decreased by 10%, while HDL-cholesterol levels remained unchanged. This provided a reduction instead of an increase in the number of participants with hypercholesterolemia, permitting the selection of individual candidates for further pharmacological treatment by carefully evaluating risk–benefit costs. Recently it was reported that the Mediterranean diet was found to be ideal for post-transplantation patients without serious pathologic dyslipidemia.69 Moreover, it was concluded that in the case of patients with substantial dyslipidemia, appropriate pharmacologic treatment lowering proatherosclerotic lipid levels should be used in combination with the Mediterranean diet.

A further benefit that has been attributed to the Mediterranean diet for patients with kidney disease is that the diet, being rich in seafood and vegetables, was associated with less interdialytic weight gain compared with a diet rich in protein and carbohydrates.70

Given that T2DM is a risk factor for developing kidney disease, recently it has been reported that adherence to a Mediterranean diet may delay the use of antihyperglycemic drug therapy in patients with newly diagnosed T2DM, thereby extending an additional benefit to the kidneys.71

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet

The association between obesity, hypertension and nephrolithiasis has been recently reviewed.72 The review concluded that adopting a lower sodium diet with increased fruits and vegetables and low-fat dairy products (e.g. as stipulated in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet) may be useful for the prevention of both kidney stones and hypertension. It was also suggested that in those patients in whom dietary modification and weight loss was ineffective, thiazide diuretics are likely to improve blood pressure control and decrease calciuria.

Diet plays an important role in the pathogenesis of kidney stones. A recent report has prospectively examined the relationship between a DASH-style diet and incident kidney stones in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (n = 45 821 men; 18-year follow-up), Nurses Health Study I (n = 94 108 older women; 18-year follow-up), and Nurses Health Study II (n = 101 837 younger women; 14-year follow-up). Consumption of a DASH-style diet was found to be associated with a marked decrease in kidney stone risk.73

It is interesting to note that the DASH diet has been reported to not increase albumin excretion rates despite a 3% increase in energy from the consumed protein.74

Protein diet

Low protein diets are commonly prescribed for patients with idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis.

A recent Cochrane review of 10 studies from over 40 studies with a total of 2000 patients were analysed, of which 1002 had received reduced protein intake and 998 a higher protein intake.75 The review concluded that studies investigating protein intake reductions in patients with chronic kidney disease reduced the occurrence of renal death by 32% as compared with those studies with patients on higher or on unrestricted protein intake. Also, the study concluded that the optimal level of protein intake could not be confirmed from these data. An earlier Cochrane review investigating protein intake in children with chronic renal failure found that reducing protein intake did not appear to have a significant impact in delaying the progression to end-stage kidney disease in children.76

A recent study compared the effect of very low protein diet supplemented with keto-analogs of essential amino acids (dose of 0.35g/kg/day), low protein diet (dose of 0.60g/kg/day), and free diet on blood pressure in patients with chronic kidney disease stages 4 and 5.77 It was shown that in moderate to advanced chronic kidney disease, a very low protein diet had antihypertensive effects that were likely due to a reduction of salt intake, type of proteins, and keto-analog supplementation, independent of actual protein intake.

Results of several case-control studies suggest that high consumption of meat (all meat, red meat, or processed meat) is associated with an increased risk of renal cell cancer. Recently a pooled analysis of 13 prospective studies was conducted that included 530 469 women and 244 483 men and had follow-up times of up to 7–20 years to examine associations between meat, fat, and protein intakes and the risk of renal cell cancer.78 The study concluded that consumption of fat and protein or their subtypes, such as red meat, processed meat, poultry and seafood, were not associated with risk of renal cell cancer.

In a prospective, stratified, multi-centre randomised trial, 191 children aged 2–18 years, who were diagnosed with chronic renal failure from 25 paediatric nephrology centres across Europe, were included in the study. This study was designed to determine whether a low-protein diet could slow disease progression.79 Patients were divided into 3 groups according to their primary renal disease, and then stratified based on whether their disease was progressive or non-progressive. There was random assignment to the control and diet groups. Protein intake in the diet group was 0.8 to 1.1g/kg/day, with adjustments made for age. There were no protein intake restrictions in the control group. The study continued in all patients for 2 years, and 112 of the participants agreed to continue for an additional year. There were realistic rates of compliance (66%), and no statistically significant differences in the decline of creatinine clearance were found. Furthermore no adverse effects were reported, including no adverse effects on growth from a protein-restricted diet. This study suggests that there is little value in protein restriction in paediatric chronic renal failure.

Vegetarian diet and fluid intake

A diet that is reduced in saturated fat and cholesterol, and that emphasises fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy products, dietary and soluble fibre, whole grains and protein from plant sources is advantageous for health.80

A recent epidemiological case-control study has highlighted the importance of the role of specific foods or nutrients on cancer development, in particular renal cell cancer.81 This study has reported a significant direct trend in risk for bread (highest versus the lowest intake quintile), and a modest excess of risk was observed for pasta and rice, and milk and yoghurt. Poultry, processed meat and vegetables were inversely associated with renal cell cancer risk. No relation was found for coffee and tea, soups, eggs, red meat, fish, cheese, pulses, potatoes, fruits, desserts and sugars. The results of this study provide additional clues on dietary correlates for renal cell cancer and in particular indicate that a diet rich in refined cereals and poor in vegetables may have an adverse role on renal cell cancer. It is interesting to note that subsequent to this, a study tested whether an underlying intolerance of bread ingredients was responsible for the adverse influence of bread on renal cell cancer.82 This study reported that serum levels of IgG against Saccharomyces cerevisiae may well predict survival in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. The data reported in this study suggested that it was not cereals but baker’s yeast, the critical component of bread, that may cause immune deviation and impaired immune surveillance in predisposed patients with renal cell cancer.

Approximately 80% of kidney stones contain calcium, and the majority of calcium stones consist primarily of calcium oxalate.83 Small increases in urinary oxalate can have a major effect on calcium oxalate crystal formation and higher levels of urinary oxalate are a major risk factor for the formation of calcium oxalate kidney stones.79

An RCT investigated nephrolithiasis by randomly assigning 99 participants who had calcium oxalate stones for the first time to a low animal protein, high fibre diet that contained approximately 56–64g/day of protein, 75mg/day of purine (primarily from animal protein and legumes), one-quarter cup of wheat bran supplement, and fruits and vegetables.84 After adjustment for possible confounders of age, gender, education and baseline protein and fluid consumption the study showed that the relative risk of a recurrent stone in the intervention group was 5.6 compared with the control group. It was concluded that following a low animal protein, high fibre, high fluid diet had no advantage over advice to increase fluid intake alone.

Dietary oxalate and kidney stone risk is centred on the contribution of oxalate intake to urinary oxalate excretion. A recent study that investigated the intake of oxalate and the risk for nephrolithiasis found that the relative risks for participants who consumed 8 or more servings of spinach per month compared with fewer than 1 serving per month were 1.30 for men and 1.34 for older women.85

Foods high in oxalic acids include rhubarb, spinach, beans, eggplant, garlic, cauliflower, broccoli and carrots. Fluids high in oxalic acids include cranberry juice, orange juice, black tea and cocoa. Reducing the intake of these foods and/or fluids in patients with renal impairment and/or those with a tendency to oxalate calcium may help.86

For secondary prevention of nephrolithiasis a recent Cochrane review that determined efficacy and safety of diet, fluid, or supplement interventions found that high fluid intake decreased risk of recurrent nephrolithiasis. The review also found that reduced soft drink intake lowered risk in patients with high baseline soft drink consumption.87 (See also ‘Water intake’ later this chapter.)

Along a related trend of enquiry, a prospective study that examined the relationship between fructose intake and incident kidney stones in the Nurses Health Study I (93 730 older women), the Nurses Health Study II (101 824 younger women), and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (45 984 men) concluded that the multivariate relative risks of kidney stones significantly increased for participants in the highest compared to the lowest quintile of total-fructose intake for all 3 study groups. Moreover, free-fructose intake was also associated with increased risk. Non-fructose carbohydrates were not associated with increased risk in any cohort. The study clearly suggested that fructose intake was an independent risk associated with incident kidney stones.88

A small study with 10 patients investigated dietary sodium supplementation in stone-forming patients with hypocitraturia.89 The results demonstrated that dietary sodium supplementation increased voided urine volume and decreased the relative risk super-saturation ratio for calcium oxalate stones in patients with a history of hypocitraturic calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis.

An early study investigated a vegetarian soy diet and its effects on hyperlipidemia in a prospective cross-over trial of 20 participants, aged 17–71 years (mean age 41 years) with nephrotic syndrome.90 Following a 2-month baseline period in which the patients consumed their usual diets, the participants were changed to the vegetarian soy diet for 2 months, after which they resumed their usual diet for a further 2-month washout period. The vegetarian soy diet was rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids and fibre, low in fat and protein, and free of cholesterol.

Given that changes in dietary protein consumption have important roles in the prevention and management of several forms of kidney disease, a recent review has hypothesised that perhaps by substituting soy protein for animal protein, this could decrease hyperfiltration in diabetic patients and, hence, may significantly reduce urine albumin excretion and improve renal function.93

Recently it was shown in a large prospective cohort study (375 851 participants recruited in EPIC centres of 8 countries) that total consumption of fruits and vegetables was not related to risk of renal cell cancer.94

Alcohol

An early review has reported that alcohol over-consumption has multiple effects on kidney function as well as on water, electrolyte and acid-base homeostasis.95 Increased blood pressure was demonstrated in men above 80g and in women above 40g ethanol consumption daily. In contrast, young adults consuming only 10–20g/day had lower blood pressure than the abstinent group, indicating a J-curve relationship. This is consistent with a decreased risk for coronary heart disease associated with regular consumption of small alcohol amounts. In fact, a large prospective cohort study (US Physicians Health Study) has reported that in apparently healthy men, alcohol consumption was not associated with an increased risk of renal dysfunction. Instead, the data suggested an inverse relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of renal dysfunction.96 The study reported that men who had 7 or more drinks of wine per week had a 30% lower risk of raised creatinine levels.96

Further investigations into the relationships between wine consumption and kidney disease have been limited. A recent review has reported that there is convincing evidence of a beneficial effect of controlled wine consumption in patients with renal disease.97 The evidence is built around the fact that long-term alcohol abuse has been associated with many renal alterations in humans. In experimental studies wine polyphenols enhance kidney antioxidant defences, exert protective effects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury, and inhibit apoptosis of mesangial cells. Controlled clinical trials are, however, needed to confirm the hypothesis.

The mechanisms responsible for the association between alcohol over-consumption and post-infectious glomerulonephritis remain unclear. Moreover, the severe alcohol abuse that was reported to predispose to acute renal failure appeared to be associated with general catabolic effects.89

Water intake

A report from the University of Sydney presented at the Australian and New Zealand Nephrology meeting in 2005, detailed a study that people who drank approximately 3 litres of water per day halved their risk for chronic kidney disease.98 This report needs to be verified with further studies. The study also reported that those individuals who had a higher intake of fibre (42.3g/day) also appeared to have a reduced risk for chronic kidney disease with a reduction in risk by 34%.

Coffee

It is an established fact that caffeine has a diuretic effect. Various studies have demonstrated that in healthy volunteers the acute administration of caffeine, or drinks containing it, causes a short-term increase in diuresis with a concomitant excretion of substances such as sodium, potassium, chlorides, magnesium, and calcium.99, 100, 101

Whether caffeine reduces or increases the risk for kidney stones is contentious. In the most recent study from 2004, Massey and Sutton102 demonstrated that caffeine consumption at a dose of 6mg/kg of lean mass after 14 hours of fasting in 39 volunteers caused an increase in the excretion of calcium, magnesium and citrate, with an increase in the Tiselius index for calcium oxalate stones formation from 2.4 to 3.1 in those participants with a history of calcium lithiasis and from 1.7 to 2.5 in those participants without this history. In general, the consumption of coffee seemed to increase, albeit modestly, the risk of forming calcium oxalate stones. A report in a less recent study demonstrated that the administration of caffeine in healthy young women caused an increased urinary loss of calcium and magnesium, with a significant reduction in the reabsorption percentage after its consumption whereas other parameters, such as creatinine clearance, were not modified.103

Studies on the effects of caffeine in participating patients with nephropathy or chronic renal failure, and in those on dialysis, are scarce and therefore no conclusive information can be provided. It should be noted though that studies on patient populations have shown that the consumption of caffeine during dialysis might become a useful semi-pharmacologic option for the prevention and treatment of symptomatic intradialytic hypotension.102, 103 Also it is now a strong consensus that chronic caffeine consumption does not contribute to restless leg syndrome, one of the most frequently observed disturbances of patients on haemodialysis.106, 107

Hence, from a detailed review of the current literature there are significant conflicting opinions and research data regarding the extremes of the diuretic, prolithiasic and toxic effects of caffeine.101

Nutritional supplements

Vitamins and minerals

There is limited evidence for the use of multivitamin/mineral preparations for kidney disease. Given that a decline in renal function is related directly to cardiovascular mortality, the administration of vitamins and or minerals that could benefit cardiovascular health may also be useful for maintaining kidney function.110

Folate

A cross-over RCT of 23 children/teenagers with chronic renal failure, aged 7–17 years, was conducted, whereby each participant received 8 weeks of 5mg/m2 folic acid per day and 8 weeks of placebo, separated by a washout period of 8 weeks.111 There was a significant decrease in homocysteine levels during the folic acid phase from 10.3 mol/L to 8.6 mol/L with an insignificant rise in LDL lag times during the folic acid period. Based on a significantly improved flow mediated vessel diameter in the folic acid group, the study concluded that an 8-week regimen of folic acid could improve endothelial function. Because of the inconclusive folic acid supplementation studies in adults, the authors have speculated that this positive finding might be related to timing of treatment, in that atherosclerosis in children is at an earlier stage of its natural history.111 Although folic acid is extremely safe, studies with clinically relevant outcomes are required before folate supplementation can be recommended for routine use in children with chronic renal failure.

Vitamin D

Single vitamin studies have concentrated on reducing the risk for adverse events such as in those patients with chronic kidney disease who have significant abnormalities of bone remodelling and mineral homeostasis and are at increased risk of fracture. A recent systematic study reviewed the scientific evidence of RCTs that reported the use of bisphosphonates, vitamin D sterols, calcitonin, and hormone replacement therapy to treat bone disease following kidney transplantation.112 The review found that treatment with a bisphosphonate or vitamin D sterol or calcitonin after kidney transplantation may protect against immunosuppression-induced reductions in bone mineral density and prevent fracture.

Vitamin C

The role of vitamin C in kidney oxalate urolithiasis remains a risk according to recent studies,113 particularly in those predisposed to forming kidney stones.114 A recent double-blind cross-over RCT investigated the effects of 2 different vitamin C formulations and found that vitamin C with metabolites (ester-C) significantly reduced urine oxalate levels compared to ascorbic acid.115 This study requires further evaluation with respect to inhibiting oxalate kidney stone formation.

Vitamin E/B6/B12

The Antioxidant Therapy In Chronic Renal Insufficiency (ATIC) Study showed that a multi-step treatment strategy improved carotid intima-media thickness, endothelial function, and microalbuminuria in patients with stages 2–4 chronic kidney disease. Recently an RCT116 investigated a sequential treatment consisting of pravastatin 40mg/day; after 6 months, vitamin E 300mg/day; and after another 6 months, homocysteine-lowering therapy (folic acid, 5mg/day; pyridoxine, 100mg/day; and vitamin B12, 1mg/day, all in 1 tablet) were added and continued for another year. This regimen was compared to placebo. It was concluded that analysis of separate treatment effects suggested that vitamin E significantly decreased plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) — an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (linked to greater CVD risk in patients with chronic kidney failure). Levels were reduced by 4% in the treatment group compared with the placebo group.

A study that investigated dietary supplementation of red grape juice, a source of polyphenols, and vitamin E on neutrophil NADPH-oxidase activity and other cardiovascular risk factors in haemodialysis patients found that the regular ingestion of concentrated red grape juice by haemodialysis patients reduced neutrophil NADPH-oxidase activity and plasma concentrations of oxidised LDL and inflammatory biomarkers to a greater extent than does that of vitamin E.117 This effect of red grape juice consumption may favour a reduction in cardiovascular risk and assist kidney function. The re-regulation of cellular metabolism by polyphenolic compounds may constitute a biologically plausible rescue mechanism of metabolism in patients with chronic kidney disease. Moreover, it has also been recently shown that gamma tocopherol and DHA were well-tolerated and reduced selected biomarkers of inflammation in haemodialysis patients thereby reducing the risk of cardiovascular complications in this patient population.118 Larger trials are required though for further evaluation. Also, on assessing clinical trials utilising vitamin E it is important to distinguish if the supplement and/or compound being investigated is alpha tocopherol or mixed alpha and gamma tocopherols or gamma tocopherol alone.

Magnesium

Magnesium is an essential mineral for optimal metabolic function. Studies that have demonstrated the promising effectiveness include results such as lowering the risk of metabolic syndrome and improving glucose and insulin metabolism,119 which may have an intimate association with the development of progressive renal failure. Furthermore, because the kidneys have a very large capacity for magnesium excretion, hypermagnesemia usually occurs in the setting of renal insufficiency as well as excessive magnesium intake. It has been documented that body excretion of magnesium can be enhanced by use of saline diuresis, furosemide, or dialysis, depending on the clinical situation.120 Magnesium has been implicated in diverse consequences, both beneficial and deleterious, in patients with chronic renal failure and dialysis.121 Hence, there is a requisite for prudent supplementation with magnesium for renal patients.

A recent review has reported that there is biologically plausible data available for the role of magnesium in end-stage renal disease and its possible favourable therapeutic application in these patients.122 The benefit of magnesium supplementation has been recently reported in a study with haemodialysis patients.123 Although further studies are required this study reported that magnesium could play an important protective role in the progression of atherosclerosis by protecting carotid intima media thickness in patients on dialysis.

A recent pilot study and an RCT have investigated magnesium for the control of serum phosphate.124, 125 The pilot study, investigating outpatients on haemodialysis, concluded that magnesium carbonate was generally well tolerated and was effective in controlling serum phosphorus while reducing elemental calcium ingestion. The RCT used 46 stable haemodialysis patients who were randomly allocated to receive either magnesium carbonate (n = 25) or calcium carbonate (n = 21) for 6 months. The study showed that magnesium carbonate administered for a period of 6 months was an effective and inexpensive agent to control serum phosphate levels in haemodialysis patients. It was further concluded that the administration of magnesium carbonate in combination with a low dialysate magnesium concentration avoided the risk of severe hypermagnesemia.125

Dietary factors have also been investigated as risks for the development of kidney stones. A large prospective cohort study reported that the association between calcium intake and kidney stone formation varied with age. Magnesium intake decreased and total vitamin C intake seemed to increase the risk of symptomatic nephrolithiasis.126 Given that age and body size affect the relationship between diet and kidney stones, dietary recommendations for stone prevention should be customised to the individual patient.

A recent double-blind, RCT studied 20 normo-calciuric participants randomised to either placebo or potassium-magnesium citrate (42 mEq potassium, 21 mEq magnesium, 63 mEq citrate/day) before and during 5 weeks of strict bed rest.127

Other supplements

L-arginine (amino acid supplement)

The same research group conducted a second cross-over RCT of 21 children/teenagers aged 7–17 years with chronic renal failure and previously documented endothelial dysfunction to determine the effect of dietary supplementation with oral L-arginine on the response of the endothelium to shear stress.128 Each child was given a 4-week regimen of 2.5 g/m2 or 5 g/m2 of oral L-arginine 3 times/day, and then a regimen of placebo after a 4-week washout period. A significant rise in levels of plasma L-arginine after the treatment phase was recorded, however, there was no significant improvement in endothelial function and, therefore, dietary supplementation with L-arginine was deemed not useful in the treatment of children with chronic renal failure.128

Omega-3 fatty acids (fish oils)

A significant body of research exists on the therapeutic use of omega-3 fatty acids for adults suffering from immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy.129 Recently omega-3 supplementation was reported to be significantly associated with the improvement of both renal vascular function and tubule function.130

A meta-analysis conducted in 1997 of 5 RCTs (n = 202) with fish oil reported that although the mean difference was not statistically significant there was a 75% probability of at least a small beneficial effect of supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids.131 Also, a sub-analysis on 3 of the studies indicated that omega-3 treatment may be more beneficial to more highly proteinuric patients. There was considerable heterogeneity among the 5 studies, including severity of disease, dosing, treatment duration, and length of follow-up, hence additional longer-term research with larger sample sizes is necessary.

The largest study that was included in the meta-analysis was a multi-centre double-blind RCT of 106 adults with IgA nephropathy.132 The test group (n = 55) received 12g/day of fish oil for 2 years, and the control group (n = 51) received placebo. There was a significant difference between the 2 groups with respect to the primary end point, a 50% or more increase in serum creatinine. The study concluded that 2 years of fish oil may significantly slow the rate of decline in renal function. No adverse events were reported, however, some participants in the treatment group complained of an unpleasant aftertaste after consuming the fish oil capsules. The same research group conducted a further study to assess the long-term outcome of the patients enrolled in this trial, with a mean follow-up time of 6.4 years.133 After the study, the placebo group had been un-blinded and was free to take fish oil. Seventeen patients from the original study switched to fish oil. In the long-term follow-up study, the study found that patients in the original treatment group were still at significantly less risk of reaching the primary end point than the patients in the original placebo group — including those who had switched to fish oil after the trial’s completion. Hence, commencing fish oil therapy early appears to offer patients the best clinical outcome.

Since the initial meta-analysis was published, 2 additional trials have been conducted.132, 133 One of these RCTs compared the effect of low-dose versus high-dose omega-3 fatty acid consumption in 73 patients with severe IgA nephropathy.134 For 2 years, the low-dose group (n = 37) received 1.88g of eicosapentanoic acid (EPA) and 1.47g of docosahexanoic acid (DHA) daily. The high-dose group (n = 36) received 3.76g of EPA and 2.94g of DHA daily. Using a 50% or more increase in serum creatinine as the primary end point, the study demonstrated that both dosage regimens were similarly effective in slowing the rate of decline in renal function. Additional research is required to determine the optimal dosage of fish oil to be prescribed, however, on current evidence fish oil supplementation is effective.

A second and more recent RCT with 28 adults diagnosed with IgA nephropathy assessed the effect of a low-dose regimen of omega-3 fatty acids.135 The test group (n = 14) received 0.85 g of EPA and 0.57 g of DHA twice/day for 4 years. Although the study indicated that the control group of participants (n = 14) was treated symptomatically, no treatment was specified. In both groups, hypertension was treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers, and/or calcium channel blockers. At the end of the study, significantly fewer participants in the test group had a 50% or more increase in their serum creatinine than in the control group. No adverse events were reported. The study suggested that the effect of fish oil may be dose dependent — with higher doses being more beneficial at preventing decline in renal function.

Recent studies indicate that the effect of a purified preparation of omega-3 fatty acids on proteinuria in patients with IgA nephropathy was dose dependent and was associated with a dose-dependent effect of the FAs on plasma phospholipid EPA and DHA levels.136

A recent meta-analysis137 that consisted of 17 trials with 626 participants investigated participants in the trials with a single underlying diagnosis such as IgA nephropathy (n = 5), diabetes (n = 7), or lupus nephritis (n = 1). The dose of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs) ranged from 0.7 to 5.1g/day, and the median follow-up was 9 months. The study concluded that omega-3 LCPUFAs supplementation reduced urine protein excretion but not the decline in glomerular filtration rate.137

A recent RCT investigating the combined treatment of proteinuric IgA nephropathy with renin-angiotensin system blockers and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) reported efficacy with PUFAs.138 This study tested the effect of a 6-month course of PUFA (3g/day) in a group of 30 patients with biopsy-proven IgA neuropathy and proteinuria already treated with renin-angiotensin system blockers randomised to receive PUFA supplementation or to continue their standard therapy. The study reported reduction of proteinuria was 72.9% in the PUFA group and 11.3% in the renin-angiotensin system blockers group. A reduction of ≥ 50% of baseline proteinuria was achieved in 80% of PUFA patients and 20% of renin-angiotensin system blockers patients. Erythrocyturia was significantly lower in the PUFA group. No significant changes in renal function, blood pressure and triglycerides were observed.

When taken in recommended doses, fish oils have been reported to be extremely safe for adults.139 It should also be noted that oral daily amounts exceeding 10g of fish oil or 3g of DHA plus EPA may lead to an increased risk of bleeding. Based on the known safety and efficacy data that currently exists, there is promising evidence to warrant the inclusion of fish oil supplementation in the treatment of adult IgA nephropathy. Potential use in children warrants further investigations though.

Probiotics

A pilot study has assessed the effect of probiotics on oxaluria in 6 adults with idiopathic calcium oxalate urolithiasis and hyperoxaluria.140 The 6 patients received a daily dose of 8 × 1011 colony-forming units (CFU) of a freeze-dried lactic acid bacteria preparation for 4 weeks. There was a significant reduction in 24-hour oxalate excretion in all 6 patients compared to baseline. The mean reduction in oxaluria was 30g/day. The reduced levels persisted for at least 1 month after treatment was ceased.

Clinical trials increasingly provide a plausible biological and scientific basis for the use of probiotics in medicinal practice including urology. A recent review concluded that dietary measures and novel probiotic therapy are promising adjuncts for preventing recurrent nephrolithiasis.141

Integrative medicine approaches for treating urinary tract infections (UTIs) have included the use of probiotics and cranberry juice.142, 143 (For more information on cranberry juice see the next section).

An early study investigated infection recurrence in 41 adult women with acute lower UTIs. The participants were randomly treated for 3 days with pharmaceuticals and showed an infection eradication rate of 100% with norfloxacin and in 95% with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. UTI recurred in 29% of patients treated with norfloxacin and in 41% of those treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Post drug therapy random-isation to vaginal administration of suppositories (L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. fermentum B-24) or placebo (skim-milk suppositories) resulted in a recurrence rate of UTI of only 21%, while in patients given the placebo the recurrence rate was 47%.144

A later study145 by this same research group investigated the effects of suppositories containing the same Lactobacillus species as the previous study versus suppositories containing Lactobacillus growth factor (to enhance growth of already existing Lactobacilli). Fifty-five women (mean age 34; ≥4 UTIs in past 12 months) were randomly selected to Lactobacillus or growth factor suppositories once weekly for 12 months. At the end of 12 months both groups exhibited a 73% lower incidence of UTIs than in the 12 months prior to study onset with 1.6 per patient and 1.3 per patient in the Lactobacillus and growth factor groups, respectively.

In a small pilot study, 9 women with recurrent UTIs (≥2 in the past 12 months) used a L. crispatus vaginal suppository every other night for 1 year. Infection rates were significantly reduced from 5.0±1.6 in the year prior to treatment to 1.3±1.2 during the year of treatment.146

Some studies with probiotic suppositories for UTI prevention have not reported a benefit.147 In an RCT, 47 women (≥3 UTIs in the previous 12 months) who were assigned to L. rhamnosus or L. casei or placebo suppositories twice weekly for 26 weeks reported no significant difference on the incidence of monthly UTI between the treatment and placebo groups.

In another RCT, 30 women with a median UTI incidence of 3 in the previous 12 months were randomised to receive L. crispatus suppositories or placebo suppositories once daily for 5 days and followed for 6 months.148 The study showed that L. crispatus CTV-05 can be given as a vaginal suppository with minimal side-effects to healthy women with a history of recurrent UTI. No severe negative effects were reported, although 7 women in the treatment group only experienced asymptomatic pyuria.

In a small study of 10 adult women, L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. fermentum RC-14 was orally administered twice daily for 14 days and resulted in bacterial recovery from vaginal tissue within 1 week of commencing supplementation.149 In 6 cases of asymptomatic or intermediate bacterial vaginosis it was reported to be resolved within 1 week of therapy.

In addition, oral probiotic supplements have been shown to benefit paediatric populations. In a multi-centre RCT in 12 neonatal intensive care units, 585 pre-term newborns were randomised to oral L. rhamnosus GG (n = 295) or placebo (n = 290) once daily until discharge. Incidence of UTIs in the Lactobacillus group was 3.4% compared to 5.8% in the placebo group — clinically relevant, however not statistically significant.150 A cautionary note should be added when supplementing neonates with probiotics, as they appear to carry a higher risk of serious complications such as sepsis.

In a case report, a girl of 6 years of age with no urinary tract anatomical abnormalities experienced 3 consecutive UTIs — once a month for 3 months.151 The patient was treated with increasingly potent antibiotic regimens — the last 2 which spread to the kidneys. After the third episode and antibiotic treatment, urine was negative for E. coli but faeces was positive for a uropathogenic strain of E. coli. The patient was commenced on L. acidophilus DDS-1 twice daily for 1 month, followed by once daily for 5 months. After 2 months, the stool was negative for the pathogenic strain of E. coli. During probiotic treatment the patient had no UTI recurrence. It is of interest that when the probiotics were ceased the patient experienced a UTI within 2 weeks — caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae.151

Recent reviews have reported that despite enhanced cure rates in some studies and the evidence from the available studies that suggests that probiotics can be beneficial for preventing recurrent UTIs in women with a good safety profile,152 concerns about product stability and limited documentation of strain-specific effects prevent strong recommendations being made for the use of Lactobacillus-containing probiotics in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis.153, 154 The results of studies employing Lactobacilli for the prophylaxis of UTI remain contentious due largely to the small sample sizes investigated in the clinical trials, however this should not be misinterpreted as no evidence.

It should be noted that the best management approach to preventing recurrent UTIs, other than appropriate hygiene, is to support the immune system (see Chapter 20).

Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon)

A US survey of 117 caregivers of children being treated at a paediatric nephrology clinic reported that 29% of the parents administered cranberry products to their children for therapeutic purposes.155 Recurrent UTI was reported by 15% of the survey parents as a problem, and the use of cranberry products was 65% among children with recurrent UTI versus 23% among children with other renal problems.

A recent meta-analysis156 of 10 trials using the Cochrane criteria for inclusion summarised the cranberry trials. Of the 10 trials, 5 were cross-over and 5 were parallel group studies. Cranberry juice was used in 7 trials, while tablets were used in 4 (one trial used both). The conclusions reached were that cranberry juice significantly reduced the incidence of UTIs over a 12-month period. It seems to be most effective in women with recurrent infections than for the elderly (both genders); individuals with neurogenic bladder do not appear to derive much benefit from cranberry juice.

Recent additional systematic reviews report on clinical trials investigating the use of cranberry for UTIs.157, 158 The findings of the first Cochrane collaboration supported the potential use of cranberry products in the prophylaxis of recurrent UTIs in young and middle-aged women. However, the authors also noted that the heterogeneity of clinical study designs and the lack of consensus regarding the dosage regimen and formulation to use cranberry products made recommendations difficult to advise.157

At the same time, in a further review for the Cochrane collaboration, the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics for the prevention of recurrent UTI in children remained unclear because of the underpowered and sub-optimally designed trials.158 However, the review concluded that the studies suggested that any benefit was likely to be small, and clinical significance may be limited. The trials of complementary interventions (vitamin A, probiotics, cranberry, nasturtium and horseradish) generally gave favourable results but were not conclusive. Hence, it was further concluded that children and their families who utilise these supplements should be aware that further infections are possible despite their use.158

Herbal medicines

Herbal Western medicines have a long historical use for the treatment of pathologies of the kidneys and the urinary tract.159 Examples of herbal medicines with traditional use in uncomplicated UTIs are:

However, clinical trials as to their efficacy and safety are largely absent.

It is important to note that herbal medicines that can help with CVD, T2DM and hypertension may also indirectly assist with renal function (see Chapters 10, 13 and 19, respectively).

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

Often many of the RCTs on TCMs have been conducted in China and the results are not readily available to clinicians in Western countries. We have identified a number of RCTs and a meta-analysis that have evaluated TCMs of herbal extracts in children with nephrotic syndrome.160–163 Tripterygium wilfordii glycosides have been demonstrated to have immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects.158

In the first RCT the study analysed the response of 80 children between the ages of 1 and 13 to Tripterygium wilfordii glycosides plus prednisone (n = 39) versus the control treatment of cyclophosphamide plus prednisone (n = 41) for the treatment of relapsing primary nephrotic syndrome. Gradual reduction in prednisone doses were administered to both groups over 12–18 months. The TCM group was given 1mg/kg of Tripterygium wilfordii glycosides orally 2–3 times/day over a period of 3 months. Also, cyclophosphamide (10mg/kg/day) was given to the control group by intermittent intravenous pulse over 3–6 months. After a follow-up period of 3–7 years (mean 4.9 years). No significant difference between the relapse rates in the 2 groups was reported. The study concluded that a combination of prednisone and Tripterygium wilfordii glycosides is as effective as prednisone plus cyclophosphamide, although methodologically these were not equivalent. Less adverse events (i.e. GI upset, alopecia) were reported by the investigational group than in the control group.

The second RCT tested the efficacy of an oral liquid preparation of a combination of 10 Chinese medicinal plants (Chai-Ling-Tang) on 69 children between 5–12 years of age with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome.159 The test group (n = 37) was given decreasing doses of prednisone until they had protein-free urine for 3 weeks. This group was also given consistent doses of Chai-Ling-Tang for 1.5 years. The control group (n = 32) was treated with tapering doses of prednisone, along with 2.5mg/kg/day of cyclophosphamide for 8 weeks. Both groups were followed-up for at least 2 years. The results showed that with respect to relapse rate, time to absence of proteinuria, amount of prednisone intake, and side-effects there was no improvement in the comparative treatment group. There was, though, a trend to improvement in these measures for the TCM arm of the study. Furthermore, it was suggested that the TCM could serve as a substitute for patients who do not respond to or have severe adverse events from taking cyclophosphamide. Further research on the TCM efficacy and safety are warranted.

The third RCT investigated whether tiaojining, a combination product of 6 principle Chinese medicinal herbs, reduced the risk of infection in 660 children with nephrotic syndrome.160 The participating children ranged from 1–13 years of age. The experimental group was treated with tiaojining 3 times/day plus baseline treatment (prednisone) for 8 weeks. The control group received prednisone alone for 8 weeks. The study concluded that tiaojining was effective in the prophylaxis of infection in nephritic children. No adverse events were reported. As methodological quality was weak, further clinical studies are needed.

A systematic review of 14 RCTs (n = 524) was conducted to determine the effect of Radix astragali combined with conventional treatment for nephrotic syndrome, including prednisone and cyclophosphamide, on nephrotic adults.161 The meta-analysis showed that Radix astragali could enhance the therapeutic effect of the conventional therapies and also reduce the recurrence of primary nephrotic syndrome. Also, compared with the participants who received only conventional treatment, those receiving the investigational product/treatment had reduced 24-hour proteinuria, increased plasma levels of albumin, and reduced levels of total cholesterol. Only 1 of the included articles indicated that there were no adverse events reported. Therefore, additional studies are required to fully understand possible adverse outcomes. Dosage varied among the trials investigated from 1–4g of dried root orally 3 times/day, or a full dropper of tincture orally 2 or 3 times/day.

A systematic review of 18 randomised and quasi-randomised trials (n = 1322) was conducted to evaluate the use of rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum) in chronic renal failure patients.164 The included trials assessed rhubarb versus conventional medicine, as well as rhubarb versus TCM herbs. Rhubarb was found to be significantly more effective in treating chronic renal failure than conventional medicine alone. There was no significant difference between the efficacy of rhubarb and that of other traditional Chinese herbs in the treatment of chronic renal failure. The review concluded that rhubarb was effective in reducing the symptoms of chronic renal failure. The small participant numbers made it difficult to conclude whether rhubarb can slow or stop the long-term progression of the disease. Half the included articles reported that no adverse effects were found.162

It was concluded that rhubarb was likely to be safe when used for short periods (i.e. less than 8 days) and in low doses, but cramps and diarrhoea have been reported. Chronic use of rhubarb can lead to numerous adverse effects, including electrolyte depletion, oedema, colic, atonic colon, and hyperaldosteronism. Rhubarb leaves contain oxalic acid and are considered toxic if ingested. Patients with renal disorders should be monitored closely when using rhubarb, due to potential electrolyte disturbances.165 Dosing information for children is unavailable.

TCM in the treatment of chronic renal failure was studied in 248 adult participants aged 20–65 years.166 For 12 months, the TCM group (n = 120) was given conventional drugs (including prednisone and furosemide) in combination with 5 decoctions of traditional Chinese herbs to treat the primary disease. These herbs were specifically targeted to supplement the kidneys, as per by TCM assumptions, to invigorate blood flow. Patients were dosed and treated individually, based on their specific characteristics. Patients in the control group (n = 128) were treated with only conventional medicine for the 12-month period. Although both groups improved, significant differences were found in improved symptoms and in creatinine clearance between the 2 groups. Adverse events were not documented in this study, and safety was unknown. The study findings require further detailed research.

In a small trial, 40 patients with chronic renal failure were randomly divided into 2 groups. The trial investigated Baoyuan Qiangshen II tablet (TCM) group and essential amino acid added capoten group. The study reported improved kidney function.167 Additional clinical studies by the same research group from China further investigated the Baoyuan Qiangshen II tablet preparation. Sixty patients with chronic renal failure were divided into 2 groups randomly; the tested group treated with Baoyuan Qiangshen II tablet combined with Lotensin and the control group treated with an essential amino acid combined with Lotensin.168 It was concluded that the test treatment was significantly better than the control and that it could significantly alleviate tubular interstitial injury thereby improving renal function and enhancing the effective rate in treating chronic renal failure.

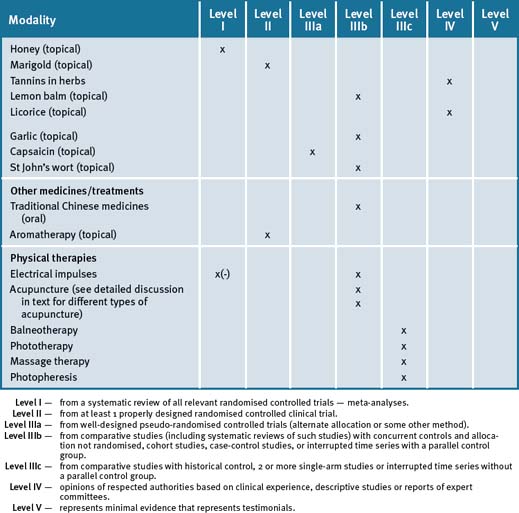

Physical therapies

Vibrational massage therapy

An early study that evaluated the use of vibrational massage therapy after extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy in 103 adults with lower caliceal stones showed benefit.169 The test group (n = 51) received shockwave lithotripsy and 20–25 minute sessions of vibrational massage therapy in 2-day intervals for 2 weeks, whereas the control group (n = 52) received shockwave lithotripsy alone. The results showed that the stone-free rates in the test and control groups were 80% and 60%, respectively. There was a significantly higher rate of stone recurrence in the control group than in the experimental group. The mean time to calculus recurrence was 16 months in the test group versus 11.4 months in the control group. There were more reports of renal colic in the control group. Additional complications, such as pyelonephritis and fever, were reported equally in both groups. Additional studies for further efficacy are warranted.

Tai chi

Tai chi is a potent intervention that improves balance, upper- and lower-body muscular strength and endurance, and upper- and lower-body flexibility. A study has found that tai chi exercise programs support current public health initiatives to reduce disability from chronic health conditions and enhance physical function in older adults.170 Moreover, a recent review has reported that tai chi exercises may reduce blood pressure and serve as a practical, non-pharmacologic adjunct to conventional hypertension management.171 This cumulative data strongly supports the use of tai chi for patients diagnosed with end-stage kidney disease.

A pilot study evaluated the effect of a tai chi based exercise training program on the QOL in a group of 9 patients on peritoneal dialysis.172 The major finding of this study was that 3 months of tai chi exercise training significantly improved the mental health dimension score in 6 patients on peritoneal dialysis.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a complex therapeutic modality that has been used to treat a variety of diseases and pathological conditions. Acupuncture has become increasingly popular as a therapy for pain and several chronic disorders, including kidney disease, that are difficult to manage with conventional treatments. Acupuncture and acupuncture-like somatic nerve stimulation have been reported in different kidney diseases and several complications related to them.173

An extensive portion of the recent scientific literature that has been published on acupuncture for the treatment of renal diseases has originated from China, such as RCTs and reviews.174–179 The studies have comprised RCTs on early interventions to treat kidney problems as well as to ameliorate symptoms associated with kidney diseases. A review of the literature between 1982 and 2007 has concluded that acupuncture and moxibustion can increase human immunity, reduce urinary protein, improve renal function, antagonise the side-effects of glucocorticoid hormones and that medication combined with acupuncture-moxibustion has the advantages of convenience, lower costs, safety and with no adverse effects.177

A randomised trial to evaluate the effect of acupuncture compared to a conventional analgesic in the treatment of 38 adult males with renal colic from urolithiasis was found to be effective.180 The severity of renal colic was assessed before treatment and 30 minutes following treatment. The mean pain scores were not significantly different between groups prior to treatment. The experimental group (n = 22) received acupuncture treatment, and the active control group (n = 16) received an intramuscular injection of avafortan (analgesic/antispasmodic). There was no significant difference in the reduction in mean pain score between the 2 groups. However, acupuncture had a significantly faster analgesic onset. There were no adverse effects with the acupuncture group.

An RCT was recently completed that investigated the efficacy of acupuncture in 68 adults with uremic pruritis.181 Patients in the test group (n = 34) were treated with acupuncture in 30-minute sessions twice a week for 4 weeks while receiving haemodialysis. For comparisons the control group (n = 34) was treated with 4mg of Chlor-Trimeton 3 times daily and a topical dermatitis ointment 3 times daily for 2 weeks along with haemodialysis. Patients were then observed for the alleviation of pruritus. The effective rate was 95% in the acupuncture group, significantly higher than the effective rate of 70.6% in the control group. Sixteen patients in the acupuncture group maintained this improvement for 3 months and 18 patients for 1 month. Conversely, in the control group, all cases experienced recurrence of uremic pruritus immediately once treatment was ceased.181 Given that safety data for acupuncture is high, some clinicians may want to consider including acupuncture for patients with uremic pruritus.

Acupressure

An additional RCT study investigated the effects of acupressure in 60 adults with uremic pruritus.182 Acupressure is part of TCM and involves pressing and/or massaging various acupuncture points on the body. The treatment group (n = 30) received acupressure in 15–20 minute sessions 3 times per week for 5 weeks either immediately before or after dialysis. Conversely the control group (n = 30) did not receive any treatment other than dialysis. Frequency, intensity, and localisation of pruritus as well as its effects on the patient’s QOL were used to assess the efficacy of acupressure on pruritus. There were significant differences in mean pruritus scores between the 2 groups after 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 18 weeks — with the acupressure group having significantly lower scores. The report concluded that acupressure was thought to be even safer than acupuncture, as it avoids needle insertion. Acupressure is a further modality for clinicians to consider for patients with pruritus.

A double-blinded RCT has reported that adult patients receiving acupressure along with conventional care returned a better quality of sleep and QOL than those not receiving any acupressure.183 Ninety-eight patients experiencing sleep disturbances were randomly assigned to an acupressure group (n = 35), a placebo group (n = 32), or a control group (n = 31). The acupressure group received acupoint massage during haemodialysis 3 times a week for 4 weeks. The placebo group received sham acupressure, which involved massage on non-acupoints which were of similar frequency and duration as the acupressure group, whereas the control group received only standard care. Data was collected at baseline and at 1 week post-treatment. After treatment, sleep quality and QOL scores were significantly more improved in the acupressure group than in the control group. Interestingly, sham acupressure also had similar improvements.183

A further RCT assessed the effect of a combined acupressure/massage regimen on fatigue and depression in 58 end-stage renal disease patients receiving haemodialysis.184 Patients were randomly assigned to either the acupressure group (n = 28) or the control group (n = 30). The acupressure group received 12 minutes of acupressure plus 3 minutes of lower limb massage 3 times a week during dialysis for 4 weeks. The control group received only routine care during dialysis. After the 4-week study period, there were significant differences in the perceived fatigue and feelings of depression (for depression this was borderline significant) between the 2 groups. This study shows promise, though further studies are warranted.

Aromatherapy

The effects of aromatherapy combined with massage was investigated in a small trial of 29 patients aged 26–65 years with uremic pruritis.185 The test group (n = 13) received aromatherapy with massage 3 times per week for 1 month, along with haemodialysis. Lavender oil and tea tree oil were used in the aromatherapy group. The control group (n = 16) received only haemodialysis during the study period. Frequency, severity, and location of pruritus were assessed and pre-test scores were not significantly different between the groups. Following the treatment period the pruritus scores were significantly lower in the test group versus the control group.

Homeopathy

A small double-blinded RCT186 assessed the effect of individualised homeopathic treatments on 28 adults (19 completed the study) with uremic pruritus who were on haemodialysis. Those in the test group received a homeopathic treatment, whereas those in the control group were given a placebo. The study had a 60-day follow-up period after starting treatment. In total, 40 homeopathic medications were prescribed, with each patient in the test group receiving more than 1 throughout the course of the study. Although there was a significant decrease in pruritus scores in the treatment group, the difference in post-treatment scores was not significant between the 2 groups at the end of the study.186 The study methodology was weak.

Conclusion

As a final thought, a recent systematic review has investigated health-related QOL factors as predictors of mortality in end-stage renal disease.187 This study overwhelmingly concluded that health-related QOL factors predict mortality in end-stage renal disease. The physical domains and nutritional biomarkers are those factors that were most closely associated with the highest health-related QOL.

Clinical tips handout for patients — renal disease

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

Rest and stress management

4 Environment

5 Dietary changes

6 Physical therapies

The following physical therapies may help (see text for further detail):

Aromatherapy may help relieve uremic pruritis (itchy skin) from kidney disease.

7 Supplements

Fish oils

Vitamins and minerals

Vitamin B group, especially B6 and B12

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol 1000IU)

Doctors should check blood levels and suggest supplementation if levels are low.

Natural vitamin E

Magnesium carbonate

Cranberry juice

1 US Renal Data System. USRDS 2008 Annual Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health; 2008. http://www.usrds.org/default.asp (accessed June 2009)

2 Coresh J., Selvin E., Stevens L.A., et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2038-2047.

3 Rabkin R. Diabetic nephropathy. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5(2):1-11.

4 Nowack R., Ballé C., Birnkammer F., et al. Complementary and alternative medications consumed by renal patients in southern Germany. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19(3):211-219.

5 Tindle H.A., Davis R.B., Phillips R.S., Eisenberg D.M. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults:1997-2002. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11:42-49.

6 Neff G.W., O’Brien C., Montalbano M., et al. Consumption of dietary supplements in a liver transplant population. Liver Transplant. 2004;10:881-885.

7 Liu J.P., Manheimer E., Yang M. Herbal medicines for treating HIV infection and AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3. CD003937. 2005.

8 Chen L.C., Chen Y.F., Yang L.L., Chou M.H., Lin M.F. Drug utilization pattern of antiepileptic drugs and traditional Chinese medicines in a general hospital in Taiwan—a pharmaco-epidemiologic study. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25:125-129.

9 Yeh G.Y., Eisenberg M.M., Davis R.B., Phillips R.S. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among persons with diabetes mellitus: results of a national survey. Am J Pub Health. 2000;92:1648-1652.

10 Tilburt J.C., Miller F.G. Responding to medical pluralism in practice: a principled ethical approach. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(5):489-494.

11 Burrowes J.D., van Houten G. Use of alternative medicine by patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2005;12:312-325.

12 Markell M.S. Potential benefits of complementary medicine modalities in patients with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2005;12(3):292-299.

13 Zhou X.J., Rakheja D., Yu X., et al. The aging kidney. Kidney Int. 2008;74(6):710-720.

14 Mokdad A.H., Ford E.S., Bowman B.A., et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors 2001. JAMA. 2003;289(1):76-79.

15 Poirier P., Giles T.D., Bray G.A., et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association scientific statement on obesity and heart disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113(6):898-918.

16 Iseki K., Ikemiya Y., Kinjo K., et al. Body mass index and the risk of development of end-stage renal disease in a screened cohort. Kidney Int. 2004;65(5):1870-1876.