Relief of Cervical Stenosis

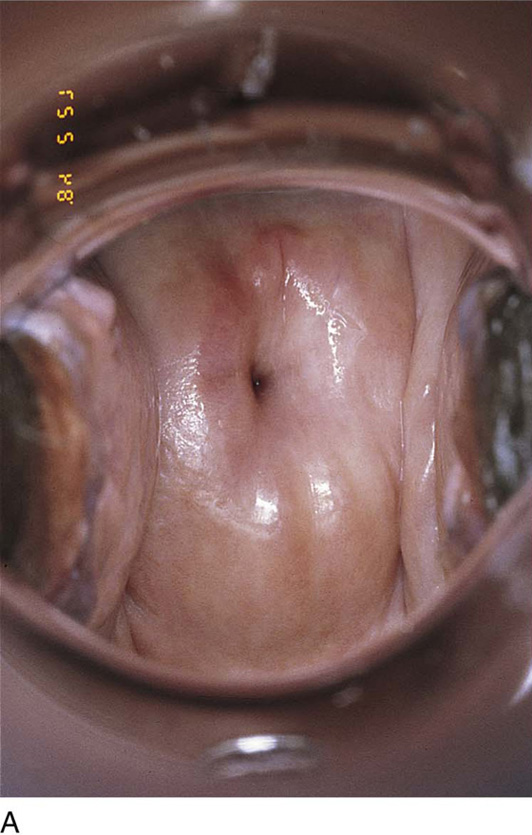

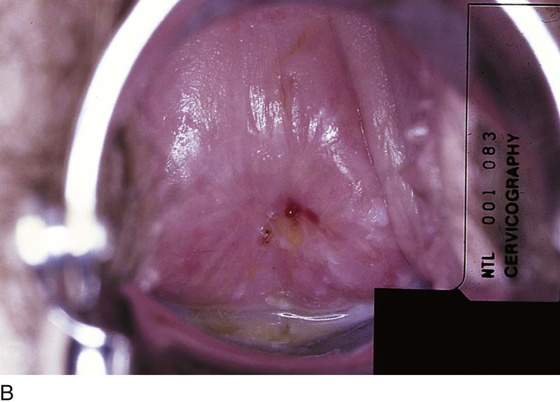

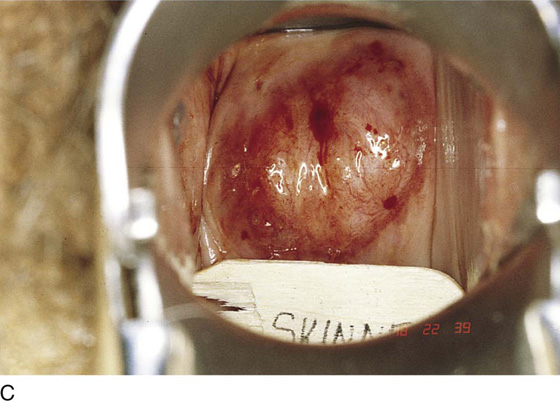

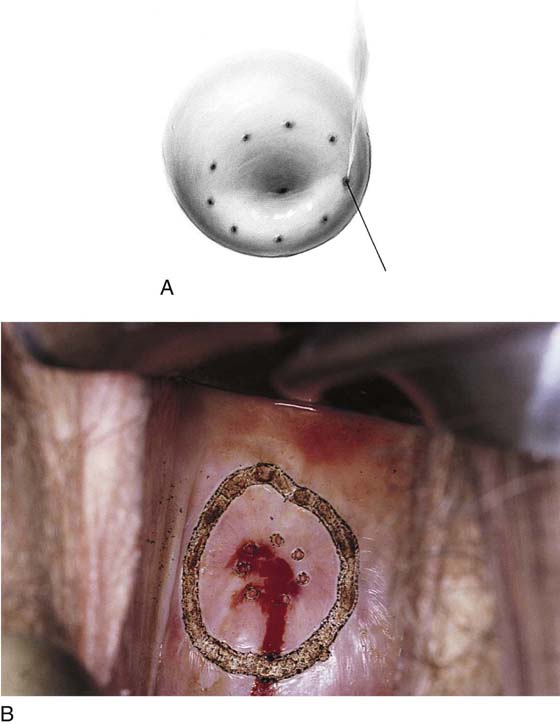

Cervical stenosis is defined as a scarred endocervical canal measuring 1 mm or less in diameter. The stenosis ranges from mild at 2 mm to a pinhole opening of less than 0.5 mm (Fig. 48–1A through C). On occasion, the opening to the shrunken canal is marked only with a dimple. The cause of this problem is basically a quantitative reduction in cervical mucous glands secondary to obstetric trauma, sharp conization, electrosurgery, laser surgery, cryosurgery, or amputation. Dilatation and curettage, traumatic endocervical aspiration, and endocervical curettage more often lead to mild narrowing at the external os or adhesions rather than to true stenosis of the canal.

The diagnosis is made colposcopically and by the insertion of a small probe (Baby Hegar dilator) that measures 2 mm on one end and 1 mm on the other (Fig. 48–2). If required, a smaller lacrimal probe may be inserted into the canal with the intent to pass it along the canal’s axis into the endometrial cavity.

The simplest therapeutic measure is directed at gently and gradually dilating the canal. It is advised to start with the Baby Hegar dilator and continue the dilatation with tapered Pratt dilators. This procedure should be repeated weekly in the office setting for 4 weeks. The patient should be checked and, if necessary, redilated monthly for 6 months. This method is useful for mild stenosis but is generally ineffective in more severe cases.

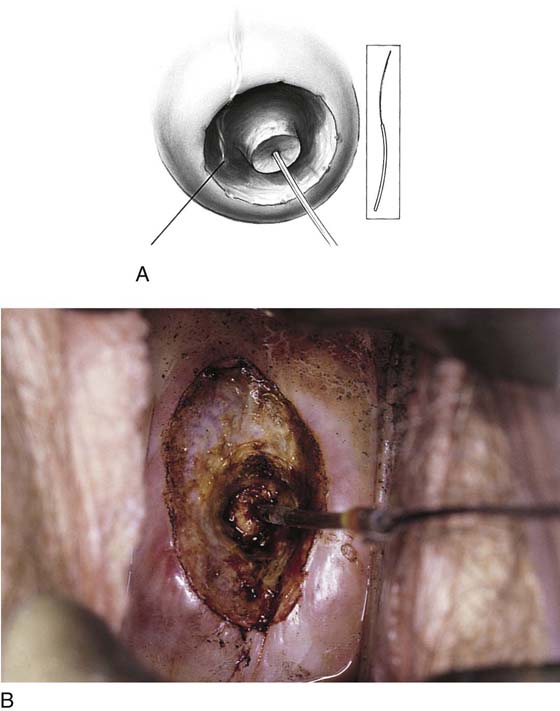

Severe stenosis can be relieved by removing the fibrotic tissue, finding viable glandular cells, exteriorizing them, and finally enlarging the canal. This technique requires a precision microsurgical procedure, which can and should be done by means of a superpulse-capable carbon dioxide (CO2) laser coupled to the operating microscope via a micromanipulator. Small beam diameters (1 mm) must be used..

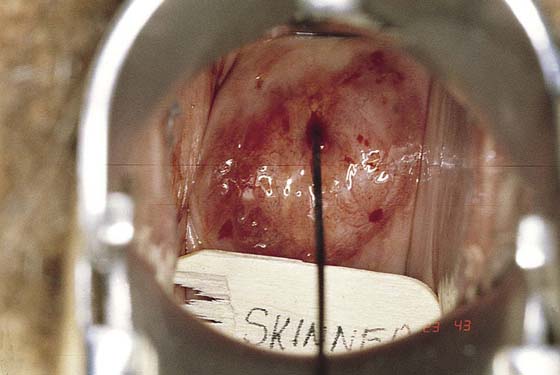

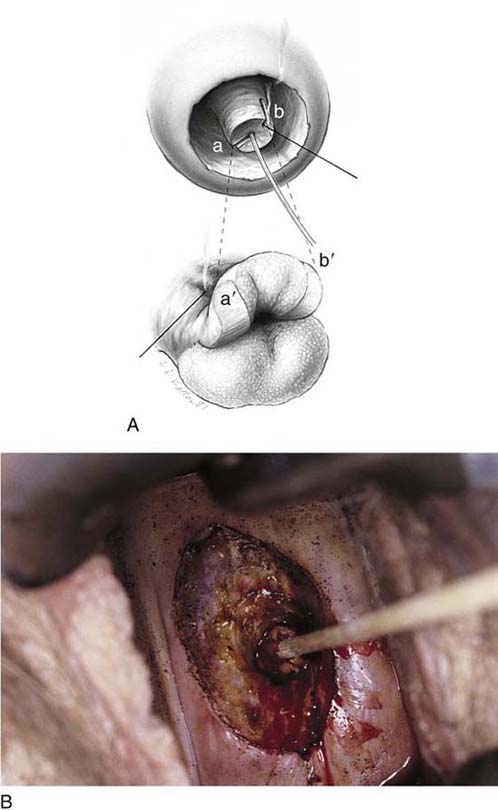

If a canal opening can be seen when the colposcope is used for magnification, a small probe can be inserted and gently advanced through the endocervical canal. Next, a 1 : 100 dilute vasopressin solution is injected into the cervix. The laser is set at 10 to 12 W ultrapulse, and trace spots are placed around the canal (Fig. 48–3A, B). The scar tissue around the canal is then vaporized layer by layer until orange-red endocervical mucosa is seen (Fig. 48–4). At this point, the endocervical canal is split by two radial cuts made from the center of the canal (probe) to its peripheral margin (Figs. 48–5A, B and 48–6A). A moist cotton-tipped applicator may be inserted through the canal and into the lower corpus of the uterus (Fig. 48–6B). Next, laser power is reduced to 5 to 10 W, and the beam is fired at the submucosal margin of the endocervical mucosa, thereby causing it to evert (see Fig. 48–6A). The field is irrigated with warm saline to expunge the carbonized, devitalized tissue.

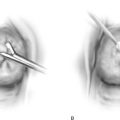

Postoperatively, the patient is placed on the equivalent of 5 mg of conjugated estrogen (Premarin) per day for 30 days (Fig. 48–7).

FIGURE 48–1 A. This cervix has been coned. The length has diminished by 30%, and the canal is moderately stenotic. B. Severe stenosis. The external os is located at the spot where a drop of blood is seen. C. Very severe stenosis. A pinhead opening is located centrally in this cervix.

FIGURE 48–2 A Baby Hegar dilator is inserted in an attempt to enlarge the small opening in the cervical canal.

FIGURE 48–3 A. Following the injection of vasopressin, a superpulse laser is used to fire several trace spots into the cervix in preparation for reconstruction of the endocervical canal. B. The trace spots are connected 3 to 5 mm circumferential to the central stenotic opening of the cervical canal. The goal of this phase of the surgery is to vaporize the surrounding dense scar tissue to release the canal.

FIGURE 48–4 The peripheral scar tissue has been vaporized. Flexible tissue beneath the scar can be seen and palpated.

FIGURE 48–5 A. The Baby Hegar dilator is again inserted into the cervical canal. B. Once the canal has been released from the surrounding scar tissue, a greater degree of dilatation can be realized. Note that the 2-mm end of the dilator can now be accommodated.

FIGURE 48–6 A. Red endocervical mucosa can now be recognized. The laser beam is tightly focused, and the canal is opened from the 1 o’clock position to 7 o’clock. The laser spot is then enlarged to 2 mm, and power is reduced to 5 to 10 W and is played directly behind the endocervical mucosa, resulting in eversion of the mucosa. B. A moist cotton-tipped applicator can be inserted through the now-enlarged canal.

FIGURE 48–7 Six weeks postoperatively, a nonstenotic endocervical canal is visible.