Chapter 13 Rehabilitation of Primary and Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions

CLINICAL CONCEPTS

The two anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) postoperative rehabilitation protocols described in this chapter consist of a careful incorporation of exercise concepts supported by the scientific data presented in Chapter 12, Scientific Basis of Rehabilitation after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Autogenous Reconstruction. The protocols are evaluation-based; that is, progression through the program is based on continual evaluation using the principles of anatomy, physiology, biomechanics, and surgery 2–5,7,14–17 and understanding that the overall goals of the reconstruction and rehabilitation are to

Regain normal knee stability (<3 mm of increased anteroposterior [AP] displacement on knee arthrometer testing, negative or trace pivot shift).

Regain normal knee stability (<3 mm of increased anteroposterior [AP] displacement on knee arthrometer testing, negative or trace pivot shift). Regain normal proprioception, balance, coordination, and neuromuscular control for desired activities.

Regain normal proprioception, balance, coordination, and neuromuscular control for desired activities. Concomitant major operative procedures including meniscal repair, ligament reconstruction, patellofemoral realignment, articular cartilage restorative procedure, and osteotomy.

Concomitant major operative procedures including meniscal repair, ligament reconstruction, patellofemoral realignment, articular cartilage restorative procedure, and osteotomy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or arthroscopic evidence of major bone bruising or articular cartilage damage.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or arthroscopic evidence of major bone bruising or articular cartilage damage.

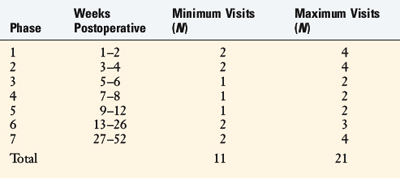

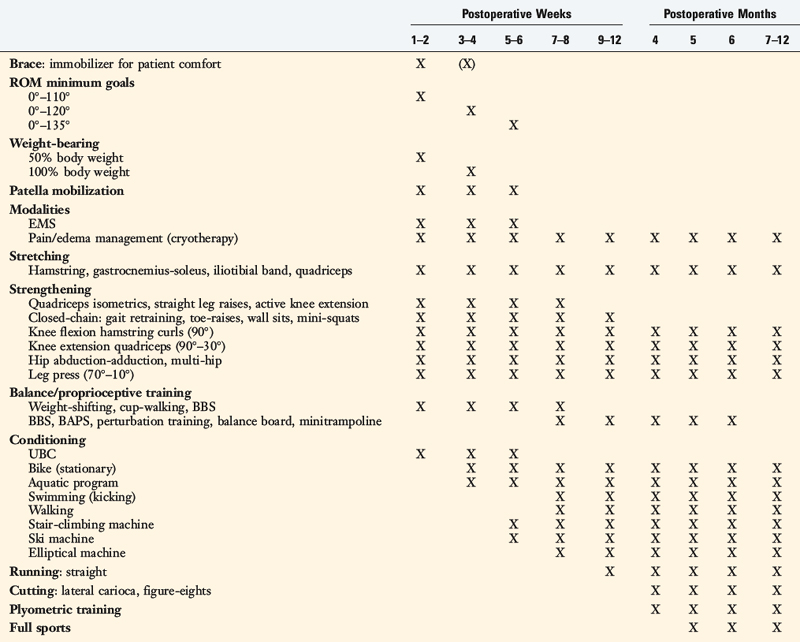

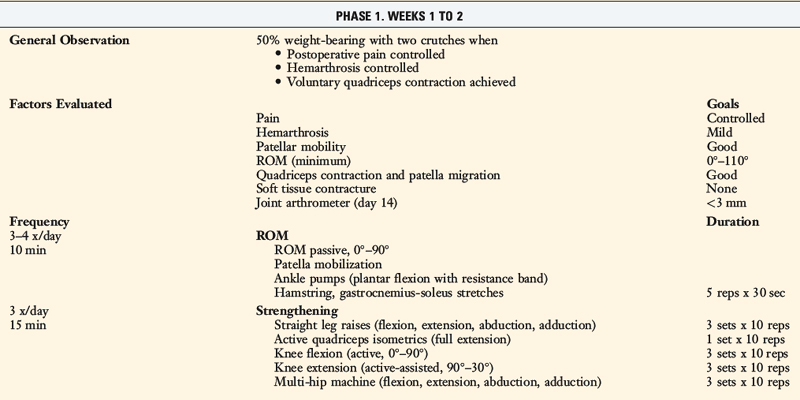

Specific criteria are evaluated throughout both rehabilitation programs to determine whether the patient is ready to progress from one phase to the next. Both protocols incorporate a home self- management program, along with an estimated number of formal physical therapy visits (Table 13-1). For most patients, 11 to 21 postoperative visits are expected to produce a desirable result. A few more supervised sessions may be required between the 6th and the 12th postoperative month for patients who undergo advanced training to return to strenuous activities. A specific neuromuscular-retraining program (Sportsmetrics) is advocated for all patients returning to high-risk activities, discussed in Chapter 19, Decreasing the Risk of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes. For all patients, the following signs are continually monitored postoperatively: joint swelling, pain, gait pattern, knee moion, patellar mobility, muscle strength, flexibility, and AP displacement. Any individual who experiences difficulty progressing through the protocol or who develops a complication is expected to require additional supervision in the formal clinic setting.

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL FOR PRIMARY ACL B-PT-B AUTOGENOUS RECONSTRUCTION: EARLY RETURN TO STRENUOUS ACTIVITIES

Modalities

In the immediate postoperative period (1–3 days), knee effusion must be controlled to avoid the quadriceps inhibition phenomenon. Electrogalvanic stimulation or high-voltage electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) may be used to augment the ice, compression, and elevation program to control swelling. This treatment uses the concept of like charges repelling. The effusion or swelling has a negative electrical charge, so using the negative electrodes at the knee and the positive (dispersive) electrode on either the low back or the opposite thigh will assist the body in removing the fluid from the joint to be reabsorbed. The treatment duration is approximately 30 minutes, the intensity is set to patient tolerance, and the treatment frequency is three to six times per day. Once the joint effusion is controlled, functional EMS is begun for muscle reeducation and quadriceps facilitation (Table 13-2).

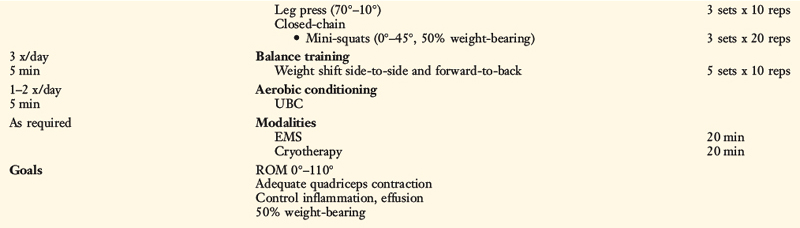

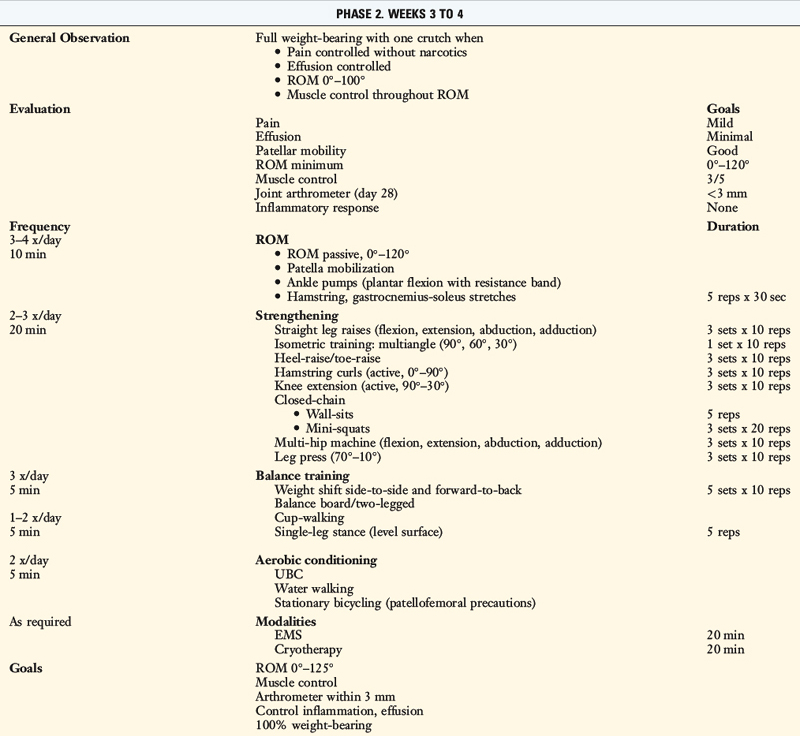

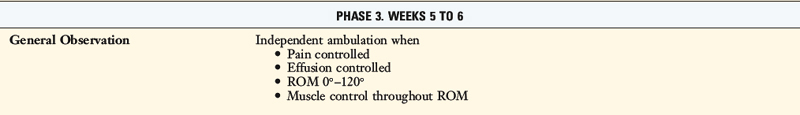

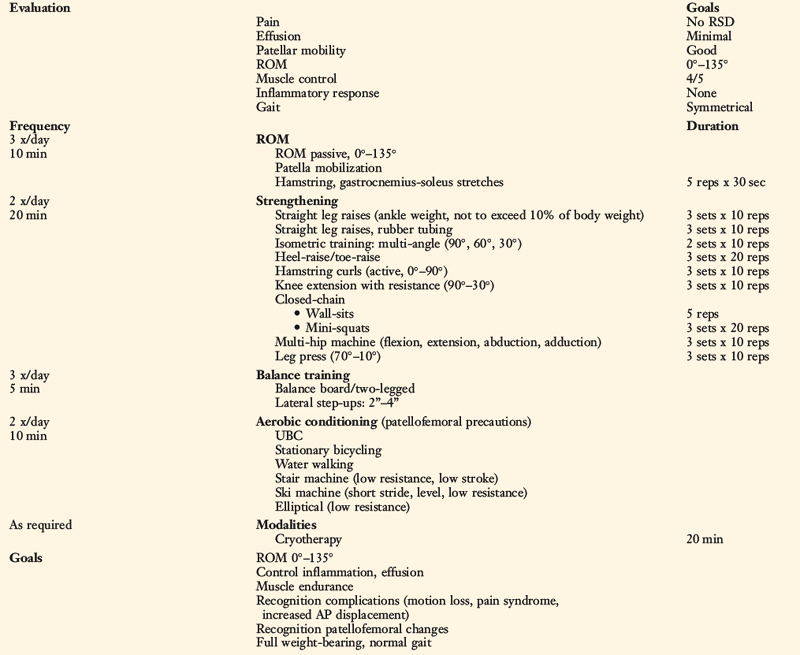

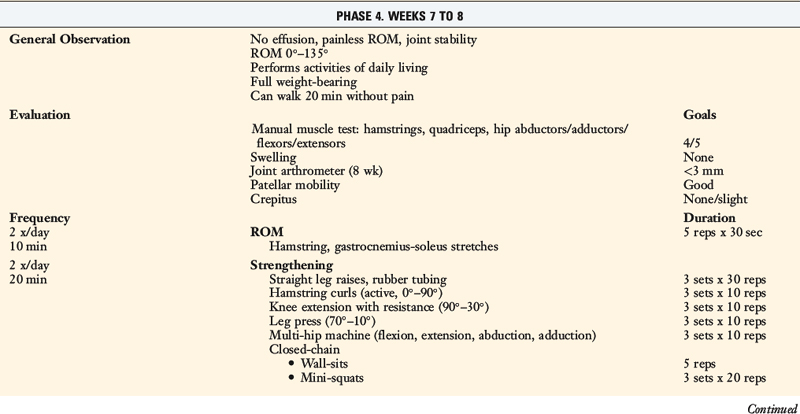

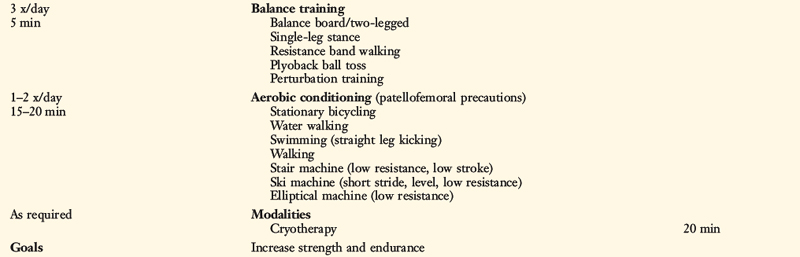

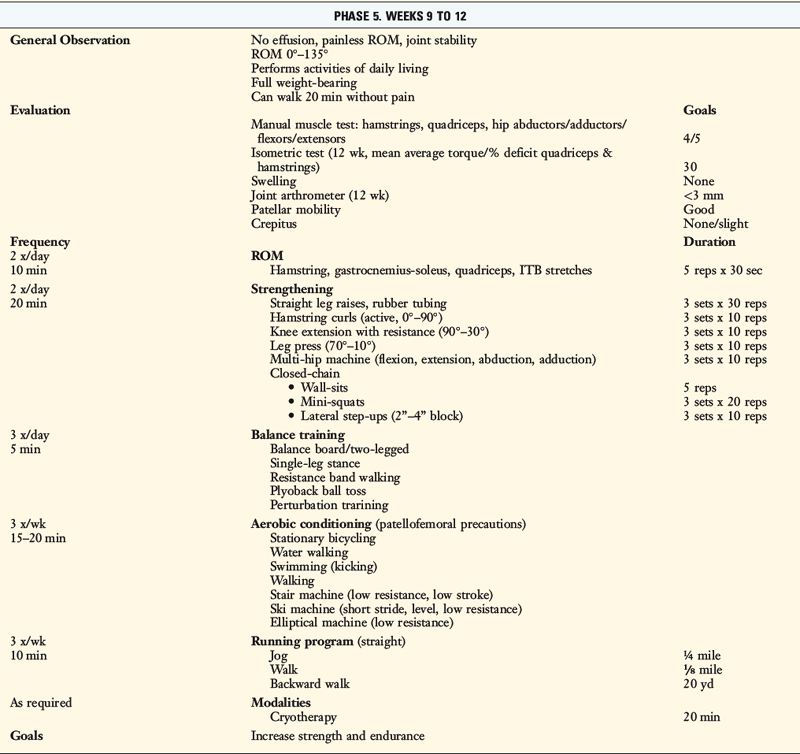

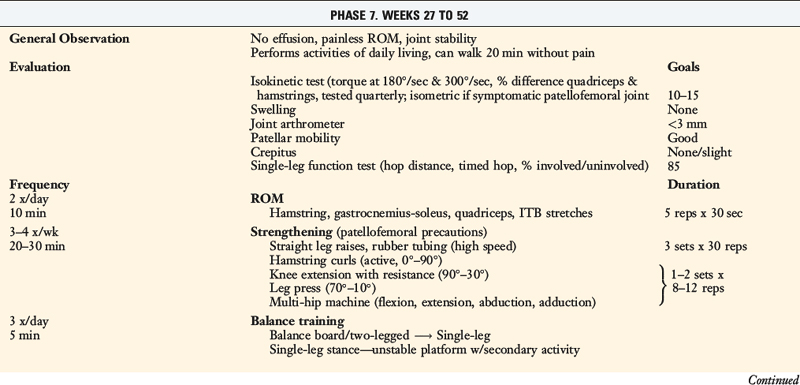

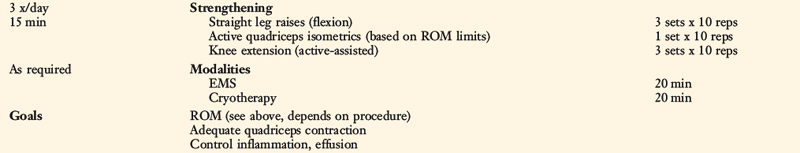

TABLE 13-2 Cincinnati Sportsmedicine and Orthopaedic Center Rehabilitation Protocol for Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Early Return to Strenuous Activities

Postoperative Bracing

Range of Knee Motion

Patellar mobilization: all four planes, done with motion exercises.

Partial weight-bearing immediately, full by 3–4 wk.

Flexibility: Hamstring, gastrocnemius-soleus, quadriceps, iliotibial band.

Strengthening

Balance, Proprioception

Running, Agility

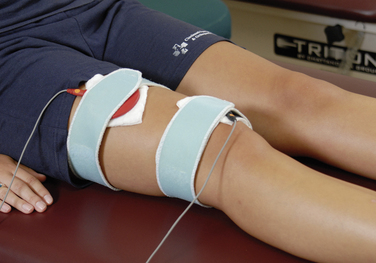

The use of EMS to facilitate and enhance an adequate quadriceps contraction is based on the evaluation of quadriceps and vastus medialis oblique (VMO) muscle tone. One electrode is placed over the VMO and the second electrode is placed on the central to lateral aspect of the upper third of the quadriceps muscle belly (Fig. 13-1). The treatment duration is 20 minutes. The patient actively contracts the quadriceps muscle simultaneously with the machine’s stimulation. A portable EMS machine for home use may be required in individuals whose muscle rating is poor. EMS is continued until the muscle grade is rated as good.

Biofeedback therapy also has an important role in facilitating an adequate quadriceps muscle contraction early postoperatively. The surface electrode is placed over the selected muscle component to provide positive feedback to the patient and clinician regarding the quality of active or voluntary quadriceps contraction (Fig. 13-2). Biofeedback is also useful in enhancing hamstring relaxation if the patient experiences difficulty achieving full knee extension secondary to knee pain or muscle spasm. The electrode is placed over the belly of the hamstring muscle while the patient performs range of motion (ROM) exercises.

The most widely used modality after ACL reconstruction is cryotherapy, which is begun in the recovery room after surgery. Cost of various cryotherapy options and patient compliance are two major factors in the successful control of postoperative pain and swelling. The standard method of cold therapy is an ice bag or commercial cold pack, which is kept in the freezer until required. Empirically, patients prefer motorized cooler units (Fig. 13-3). These units maintain a constant temperature and circulation of ice water through a pad, which provides excellent pain control. Gravity flow units are also effective; however, temperature maintenance is more difficult with these devices than with the motorized cooler units. The temperature can be controlled by using gravity to backflow and drain the water, refilling the cuff with fresh ice water as required. Cryotherapy is used for 20 minutes at a time from three times a day to every waking hour depending upon the extent of pain and swelling. In some cases, the treatment time is extended owing to the thickness of the buffer used between the skin and the device. The motorized units contain a thermostat, which is helpful when cold therapy is used for an extended treatment time. Vasopneumatic devices offer another option for cold therapy. The Game Ready device (Game Ready, Berkeley, CA) allows the clinician to set the temperature and, as well, one of four different compression levels depending on patient tolerance. Although this is primarily a clinical treatment tool, it may be used at home as well. Cryotherapy is typically done after exercise or when required for pain and swelling control and is maintained throughout the entire postoperative rehabilitation protocol.

Postoperative Bracing

The use of postoperative braces after ACL reconstruction represents a controversial area. Screening patients for personality type, pain tolerance, and program compliance may provide insight into the individual who will require brace protection postoperatively. The primary indication for the use of a brace is protection of the patient during weight-bearing in the event of a fall and to initiate early, more comfortable weight-bearing during the first few postoperative weeks. The brace should be rigid in nature and the knee held initially at 0° (Fig. 13-4). The brace is opened based on the protocol to allow normal knee flexion during ambulation. Periodic evaluation of the brace and its position on the leg must be done to ensure maximal benefit is achieved. The authors do not routinely prescribe a derotation or functional knee brace upon return to full activities after ACL reconstruction for patients in this protocol.

Range of Knee Motion

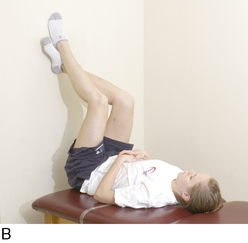

The goal in the 1st postoperative week is to obtain a ROM of 0° to 90°. A continuous passive motion machine is not required or routinely used by the authors. Patients perform passive and active ROM exercises in a seated position for 10 minutes a session, approximately four to six times per day (Fig. 13-5).

Full passive knee extension must be obtained immediately to avoid excessive scarring in the intercondylar notch and posterior capsular tissues. If the patient has difficulty regaining at least 0° by the 7th postoperative day, he or she begins an overpressure program. The foot and ankle are propped on a towel or other device to elevate the hamstrings and gastrocnemius that allows the knee to drop into full extension (Fig. 13-6A). This position is maintained for 10 minutes and repeated four to six times per day. A 10-pound weight may be added to the distal thigh and knee to provide overpressure to stretch the posterior capsule. Full knee extension should be obtained by the 2nd postoperative week. If this is not accomplished, or if the clinician notes a firm end feel, then an extension board (see Fig. 13-6B) or additional weight of 15 to 20 pounds is used six times a day. If this is still not effective, a drop-out cast (see Fig. 13-6C) is implemented for 24 to 36 hours for continuous extension overpressure. The goal is to obtain 0° to 2° to 3° of hyperextension, which is in the normal knee motion limit. In patients with physiologic bilateral knee hyperextension, the authors recommend the gradual return of 3° to 5° of hyperextension in the reconstructed knee to more closely resemble the amount of hyperextension present in the contralateral knee. However, the authors do not recommend that the patient regain more than 5° of hyperextension owing to potentially deleterious forces that may be placed on the healing graft.

FIGURE 13-6 Overpressure program for extension. A, Hanging weight exercise. B, Extension board. C, Drop-out cast.

Knee flexion is gradually increased to 120° by the 3rd to 4th postoperative week and 135° by the 5th to 6th postoperative week. Passive knee flexion exercises are performed initially in the traditional seated position, using the opposite lower extremity to provide overpressure. Other methods to assist in achieving flexion greater than 90° include chair rolling (Fig. 13-7A), wall slides (see Fig. 13-7B and C), knee flexion devices (see Fig. 13-7D), and passive quadriceps stretching exercises. Patients who have difficulty achieving 90° by the 4th week require a gentle ranging of the knee under anesthesia (not a forceful manipulation) as described in Chapter 41, Prevention and Treatment of Knee Arthrofibrosis.

Patellar Mobilization

Maintaining normal patellar mobility is critical to regain a normal range of knee motion. The loss of patellar mobility is often associated with arthrofibrosis and, in extreme cases, the development of patella infera.18–20 Patellar glides are performed beginning the 1st postoperative day in all four planes (superior, inferior, medial, and lateral) with sustained pressure applied to the appropriate patellar border for at least 10 seconds (Fig. 13-8). This exercise is performed for 5 minutes before ROM exercises. Caution is warranted if an extensor lag is detected, because this may be associated with poor superior migration of the patella, indicating the need for additional emphasis on this exercise. Patellar mobilization is performed for approximately 6 weeks postoperatively.

Flexibility

Hamstring and gastrocnemius-soleus flexibility exercises are begun the 1st day after ACL reconstruction. A sustained static stretch is held for 30 seconds and repeated five times. The most common hamstring stretch is the modified hurdler stretch (Fig. 13-9), and the most common gastrocnemius-soleus stretch is the towel pull (Fig. 13-10). These exercises help control pain owing to the reflex response created in the hamstrings when the knee is kept in the flexed position. As well, the towel-pulling exercise can help lessen discomfort in the calf, Achilles tendon, and ankle. These stretches represent critical components of the knee extension ROM program, because the ability to relax these two muscle groups is imperative to achieve full passive knee extension.

Quadriceps (Fig. 13-11) and iliotibial band (Fig. 13-12) flexibility exercises are performed to assist in achieving full knee flexion and controlling lateral hip and thigh tightness. A complete evaluation of the lower extremity will reveal deficit areas in flexibility that should be corrected. When designing a flexibility program, the therapist should take into account the particular sport or activity the patient wishes to return to as well as the position or physical requirements of that activity. Flexibility is incorporated in the maintenance program the patient performs once discharged.

Strengthening

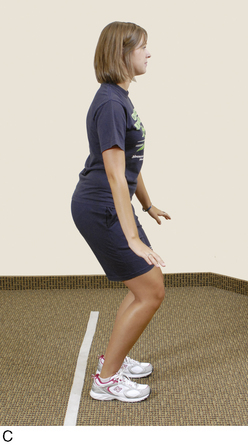

Closed kinetic chain exercises are initiated the 1st postoperative week. Mini-squats from 0° to 45° (Fig. 13-13A) are begun when tolerated by the patient. Initially, the patient’s body weight is used as resistance and gradually, TheraBand (see Fig. 13-13B) or surgical tubing is employed as a resistance mechanism. Quick, smooth, rhythmic squats are performed to a high-set/high-repetition cadence to promote muscle fatigue. Hip position is important to monitor in order to promote a quadriceps contraction.

FIGURE 13-13 Minisquats from 0° to 45° using the patient’s body weight (A) and TheraBand (B) for increased resistance.

Toe-raises for gastrocnemius-/soleus strengthening and wall-sitting isometrics for quadriceps control are begun the 2nd postoperative week. The goal of wall-sitting is to improve quadriceps contraction by performing the exercise to muscle exhaustion (Fig. 13-14A). If anterior knee pain is experienced, it may be decreased by either altering the knee flexion angle of the sit or subtly changing the toe-out/toe-in angle by no more than 10°. The exercise may also be modified to produce greater challenge to the quadriceps. The patient may voluntarily set the quadriceps muscle once she or he reaches the maximum knee flexion angle, which is typically between 30° and 45°. This contraction and knee flexion position are held until muscle fatigue occurs and the exercise is repeated three to five times. The patient may squeeze a ball between the distal thighs, inducing a hip adduction contraction and a stronger VMO contraction (see Fig. 13-14B). In a third variation, the patient holds dumbbell weights in the hands to increase body weight, which promotes an even stronger quadriceps contraction (see Fig. 13-14C). Finally, the patient can shift the body weight over the involved side to stimulate a single-leg contraction. This exercise is promoted as an excellent one for the patient to perform at home four to six times a day to achieve quadriceps fatigue in a safe knee flexion angle that does not induce an abnormal anterior tibial translation.

Lateral step-ups are begun when the patient has achieved full weight-bearing (Fig. 13-15). The height of the step is gradually increased based on patient tolerance.

Hamstring curls are begun with Velcro ankle weights within the first few weeks and eventually advanced to weight machines (Fig. 13-16). Weight machines are advantageous owing to the muscle isolation obtained as the machine provides stability to the knee joint. The patient exercises the involved limb alone as well as both limbs together. If the lightest amount of weight on the machine is too heavy to be lifted by the involved limb alone, the exercise may be performed as an eccentric contraction in which the patient lifts the weight with both legs and lowers the weight with the involved side. Eccentric contractions may also be used in the advanced stages of strength training. Hamstring strength is critical to the overall success of the rehabilitation program because of the role that this musculature plays in the dynamic stabilization of the knee joint. Weight training is used throughout the advanced program and continues in the return-to-activity and maintenance phases of rehabilitation.

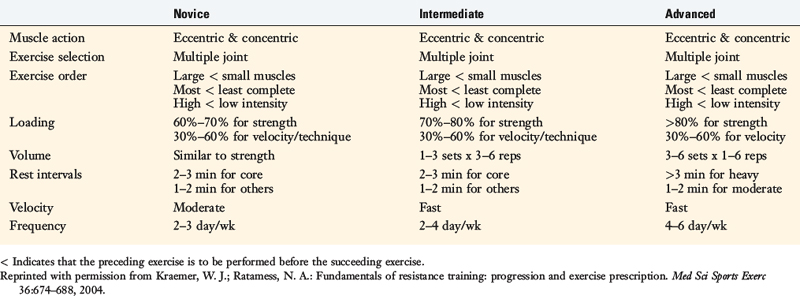

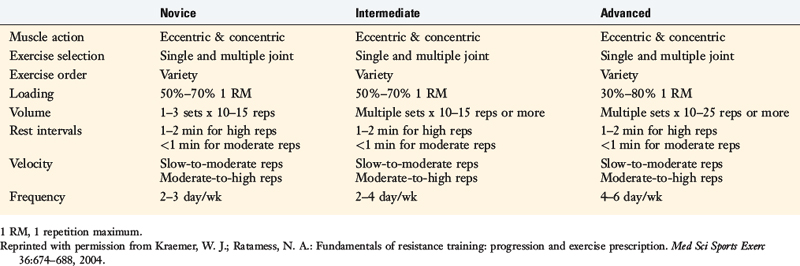

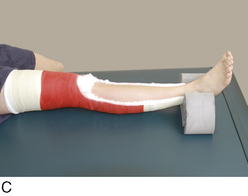

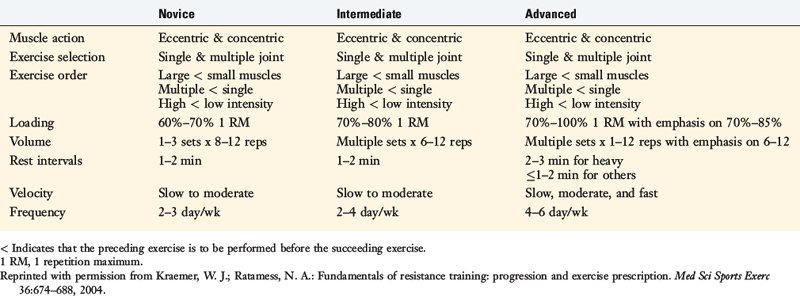

A full lower extremity–strengthening program is critical for early and long-term success of the rehabilitation program. Other muscle groups included in this routine are the hip abductors, hip adductors, hip flexors, and hip extensors. These muscle groups can be exercised on either a multi-hip or cable system machine (Fig. 13-17) or a hip abductor-adductor machine. Gastrocnemius-soleus strength is a key component for both early ambulation and the running program. In addition, upper extremity and core strengthening are important for a safe and effective return to work or sports. Sport and position specificity are taken into account when devising the strengthening program to maximize its benefits. Kraemer and Ratamess6 provided the recommendations for progression of muscle strength, hypertrophy, power, and endurance training according to the American College of Sports Medicine1 (Tables 13-3 to 13-6). Specific strengthening and sports-specific timing drills are beyond the scope of this chapter; however, the therapist should work with the patient and appropriate coaches to determine the individual patient’s program.

TABLE 13-3 American College of Sports Medicine Recommendations for Progression during Strength Training

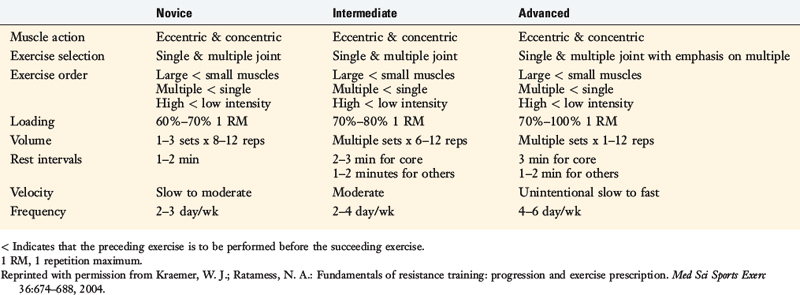

TABLE 13-4 American College of Sports Medicine Recommendations for Progression during Hypertrophy Training

Balance, Proprioceptive, and Perturbation Training

Cup-walking is begun when the patient achieves full weight-bearing (Fig. 13-18) to promote symmetry between the surgical and the uninvolved limbs. This exercise helps develop hip and knee flexion and quadriceps control during midstance of gait to prevent knee hyperextension. In addition, cup-walking controls hip and pelvic motion during midstance, gastrocnemius-soleus activity during push-off, and excessive hip hiking. These components of gait control are critical in the early phases of rehabilitation to decrease forces on the healing graft.

Double- and single-leg balance exercises in the stance position are beneficial early postoperatively. During the single-leg exercise, the foot is pointed straight ahead, the knee flexed 20° to 30°, the arms extended outward to horizontal, and the torso positioned upright with the shoulders above the hips and the hips above the ankles (Fig. 13-19A). The objective is to remain in this position until balance is disturbed. A minitrampoline or unstable platform may be used to make this exercise more challenging, because these devices promote greater dynamic limb control than that required to stand on a stable surface (see Fig. 13-19B). To provide a greater challenge, patients may assume the single-leg stance position and throw/catch a weighted ball against an inverted minitrampoline (Fig. 13-20) until fatigue occurs.

FIGURE 13-19 Single-leg balance exercise performed first on a stable surface (A) and then on an unstable surface (B).

Perturbation-training techniques are initiated at approximately the 7th to 8th postoperative week during balance exercises. The therapist stands behind the patient and disrupts her or his body posture and position periodically to enhance dynamic knee stability. The techniques involve either direct contact with the patient (Fig. 13-21A) or disruption of the platform the patient is standing on (see Fig. 13-21B).

Half foam rolls are also used in this time period as part of the gait-retraining and balance program (Fig. 13-22). This exercise helps the patient develop balance and dynamic muscular control required to maintain an upright position and be able to walk from one end of the roll to the other. A center of balance, limb symmetry, quadriceps control in midstance, and postural positioning are benefits developed through this type of training. Use of the Biomechanical Ankle Platform System (Camp, Jackson, MI) in double-leg and single-leg stance is another effective balance and proprioceptive exercise (Fig. 13-23).

FIGURE 13-23 The Biomechanical Ankle Platform System (Camp, Jackson, MI) is used in double-leg and single-leg stance.

The use of more expensive devices adds another dimension to the proprioception program, because certain units objectively attempt to document balance and dynamic control. Two of the more common units include balance systems from Biodex (Fig. 13-24) (Biodex Medical Systems, Inc., Shirley, NY) and Neurocom (Neurocom, Clackamas, OR).

Plyometric Training

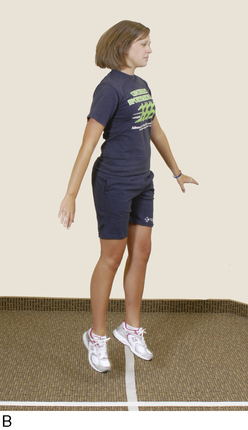

During the various jumps, the patient is instructed to keep the body weight on the balls of the feet and to jump and land with the knees flexed and shoulder-width apart to avoid knee hyperextension and an overall valgus lower limb position (Fig. 13-25). The patient should understand that the exercises are reaction and agility drills and, although speed is emphasized, correct body posture must be maintained throughout the drills.

The first exercise is level-surface box-hopping using both legs. A four-square grid of four equally sized boxes is created with tape on the floor. The patient is instructed to first hop from box 1 to box 3 (front-to-back; Fig. 13-26), and then from box 1 to box 2 (side-to-side; Fig. 13-27). The second level incorporates both of these directions into one sequence and also includes hopping in both right and left directions (e.g., box 1 to box 2 to box 4 to box 2 to box 1). Level three progresses to diagonal hops (Fig. 13-28), and level four includes pivot hops in 90° and 180° directions (Fig. 13-29). Once the patient can perform level four double-leg hops, the same exercises are done on a single leg. The next phase incorporates vertical box hops.

FIGURE 13-26 A–C, Initial plyometric training, jumping front-to-back on a level surface using both legs.

FIGURE 13-27 A–C, Initial plyometric training, jumping side-to-side on a level surface using both legs.

The authors recommend that patients complete a course of Sportsmetrics training to reduce the risk of a noncontact reinjury before return to strenuous athletics. This training program teaches athletes to control the upper body, trunk, and lower body position; lower the center of gravity by increasing hip and knee flexion during activities; and develop muscular strength and techniques to land with decreased ground reaction forces. In addition, athletes are instructed to pre-position the body and lower extremity prior to initial ground contact in order to obtain the position of greatest knee joint stability and stiffness. The program consists of a dynamic warm-up, plyometric jump training, strengthening exercises, aerobic conditioning, agility, and risk-awareness training. The training is conducted three times a week on alternating days for 6 weeks and is described in detail in Chapter 19, Decreasing the Risk of ACL Injuries in Female Athletes.

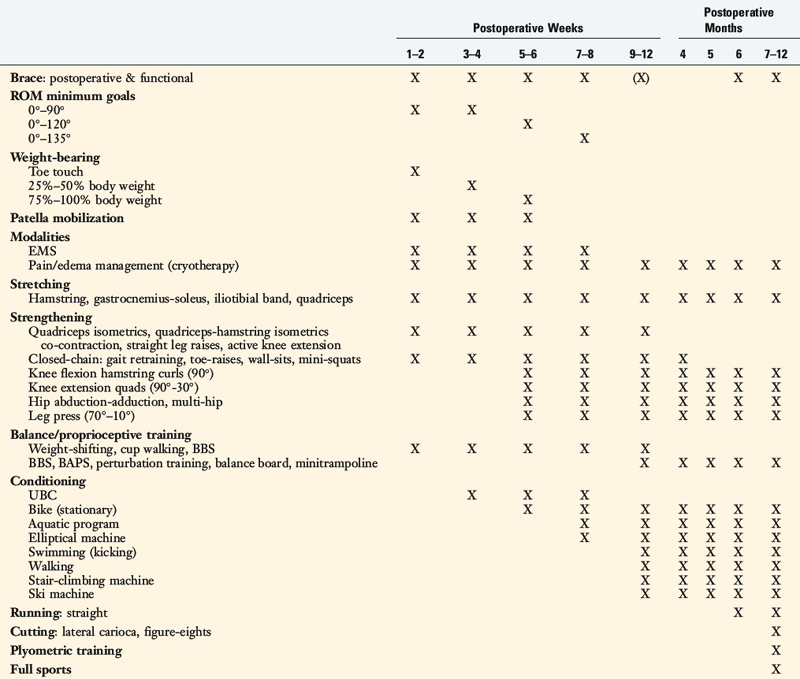

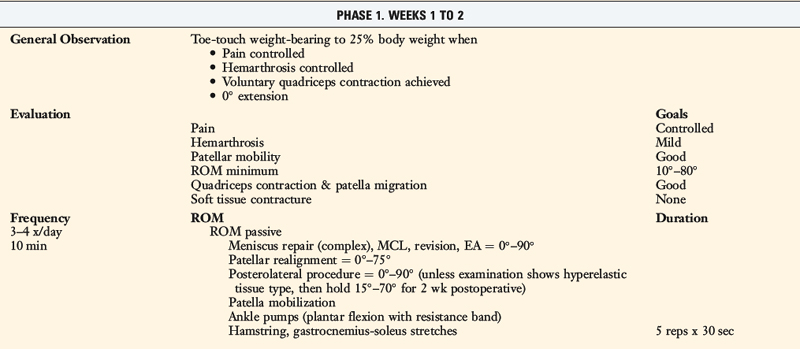

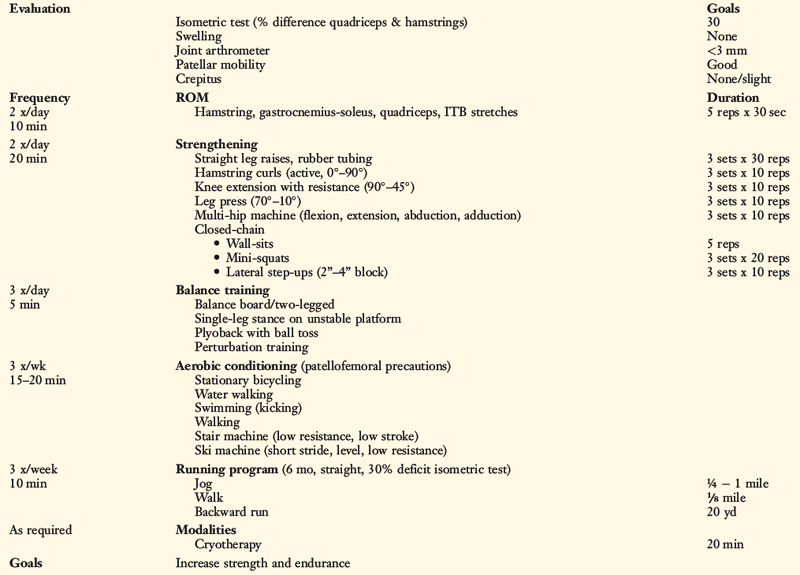

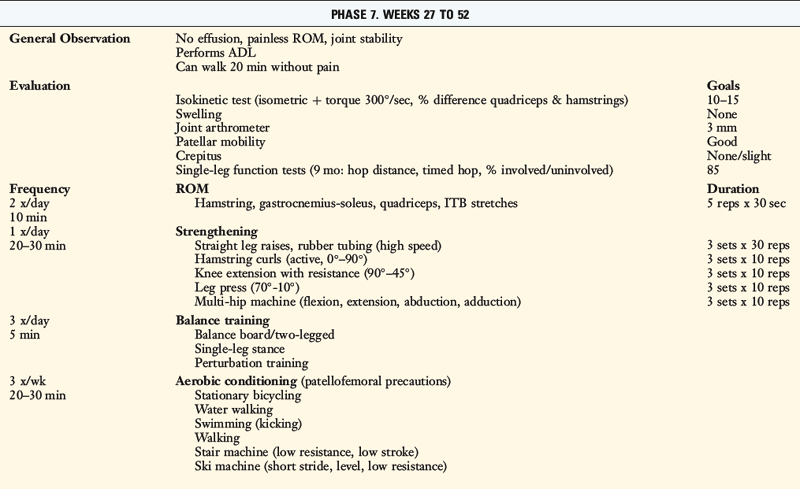

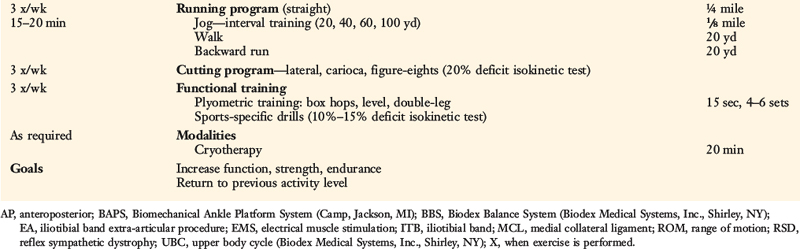

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL WITH DELAYED PARAMETERS FOR REVISION ACL RECONSTRUCTION, ALLOGRAFTS, AND COMPLEX KNEES

This protocol incorporates delays in return of full weight-bearing and knee flexion; initiation of certain strengthening, conditioning, running, and agility drills; and return to unrestricted activities (Table 13-7) for knees undergoing ACL revision,13 allograft reconstruction,8 major concomitant operative procedures, or that have noteworthy articular cartilage damage.10,11 Toe-touch-only weight-bearing is allowed for the first 2 postoperative weeks. The amount of weight patients are allowed after this time depends on the concomitant operative procedures performed as well as evaluation of postoperative pain and swelling, quadriceps muscle control, and ROM. The majority of patients are weaned from crutch support between the 6th and the 8th postoperative week.

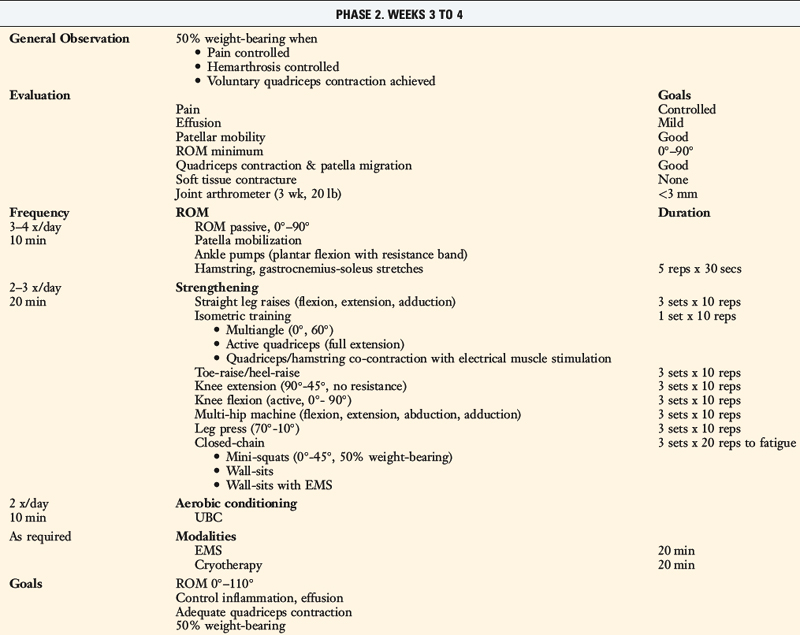

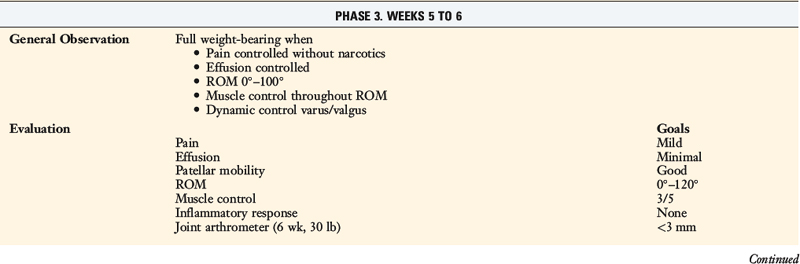

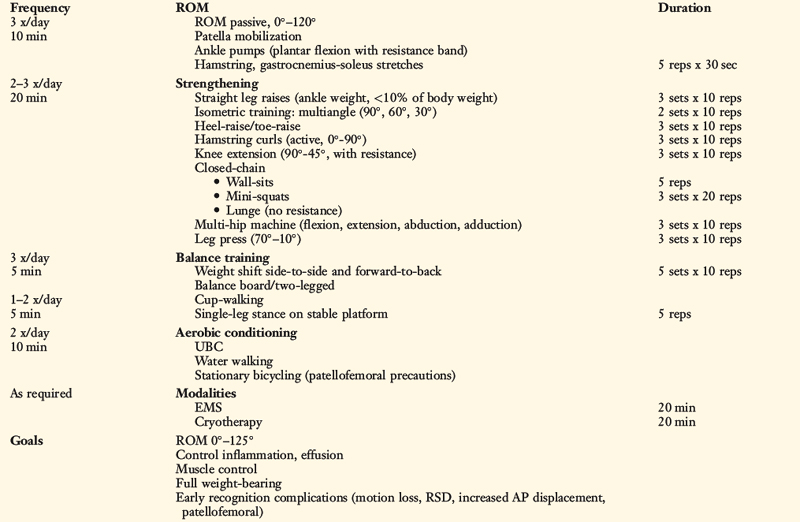

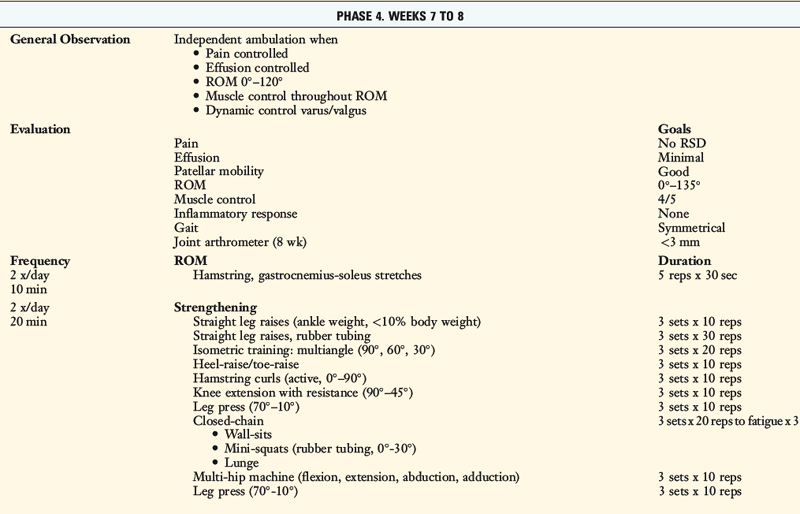

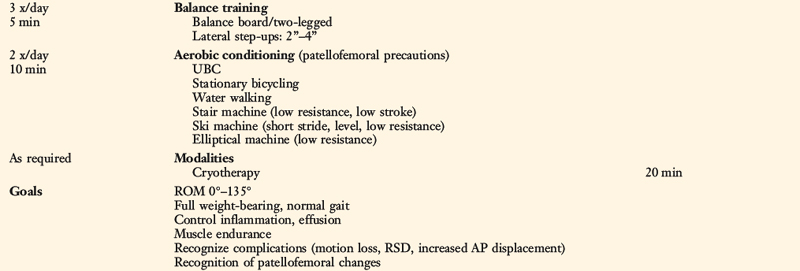

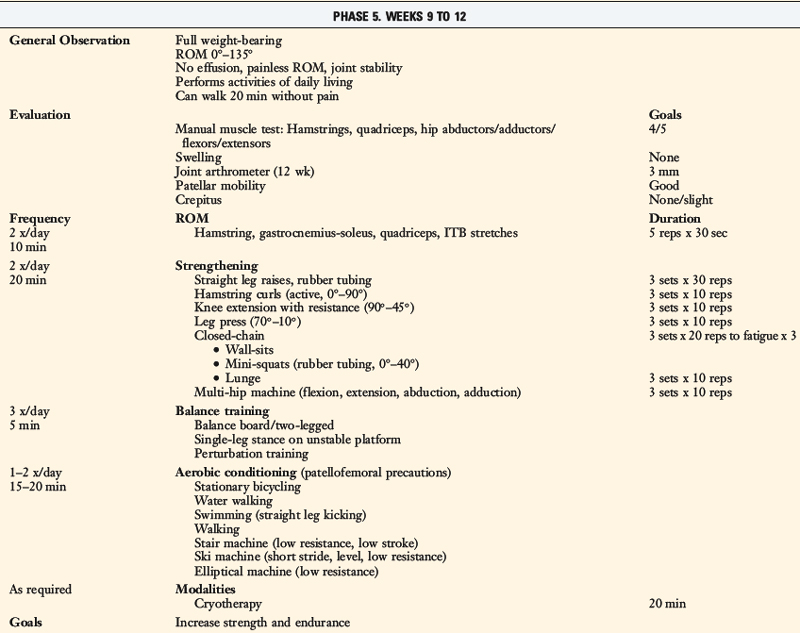

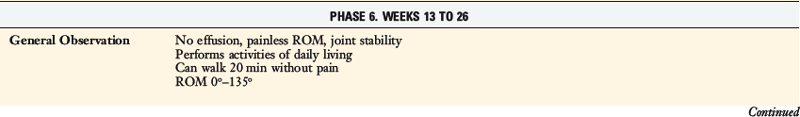

TABLE 13-7 Cincinnati Sportsmedicine and Orthopaedic Center Rehabilitation Protocol for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Revision Knees, Allografts, and Complex Knees

Allowance of knee flexion of at least 135° is delayed according to the concomitant procedure performed. Knees that undergo a posterolateral reconstructive procedure are placed into a bivalved long-leg cast for the first 4 weeks12 (see Chapter 23, Rehabilitation of PCL and Posterolateral Reconstructive Procedures). The patient removes the cast to perform ROM exercises several times a day and is instructed to reach 0° of extension but to avoid hyperextension. Patients who undergo a concomitant proximal patellar realignment are allowed 0° to 75° for the first 2 postoperative weeks. Flexion is slowly advanced to 135° by the 8th week. Knee flexion is also initially limited in knees that undergo a concomitant posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction9 (see Chapter 23, Rehabilitation of PCL and Posterolateral Reconstructive Procedures) and/or complex meniscus repair21 (see Chapter 30, Rehabilitation of Meniscus Repair and Transplantation Procedures).

Modifications in strengthening, conditioning, and strenuous training are based on the concomitant procedures performed. Return to activity is delayed until at least the 6th postoperative month to allow for healing of all repaired and reconstructed tissues and return of joint and muscle function. It is the authors’ opinion that allografts have a delay in maturation compared with autografts (see Chapter 5, Biology of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Graft Healing) and that the resultant time constraints postoperatively in terms of release to full activity are empirical at present. Evaluation is a key component to allow initiation of the functional program, which includes the assessment of symptoms and examination of knee motion, muscle strength, and ligament stability. The sum of the evaluation, not just one parameter, should determine return to function. In patients following this protocol, return to full activity is not usually expected to occur until the 9th to 12th month postoperative. It should also be noted that return to full activity does not guarantee return to preinjury activity levels. Consideration of use of a derotation or functional brace includes patients who have undergone ACL revision or multiligament reconstruction or who demonstrate an increase in AP displacement of 3 mm or more postoperatively compared with the contralateral limb. In addition, patients who are apprehensive about returning to strenuous activities or who experience a subjective sensation of instability are candidates for functional bracing.

1 American College of Sports Medicine. Position stand: progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:364-380.

2 Barber-Westin S.D., Noyes F.R. The effect of rehabilitation and return to activity on anterior-posterior knee displacements after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:264-270.

3 Barber-Westin S.D., Noyes F.R., Heckmann T.P., Shaffer B.L. The effect of exercise and rehabilitation on anterior-posterior knee displacements after anterior cruciate ligament autograft reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:84-93.

4 DeMaio M., Mangine R.E., Noyes F.R., Barber S.D. Advanced muscle training after ACL reconstruction: weeks 6 to 52. Orthopedics. 1992;15:757-767.

5 DeMaio M., Noyes F.R., Mangine R.E. Principles for aggressive rehabilitation after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Orthopedics. 1992;15:385-392.

6 Kraemer W.J., Ratamess N.A. Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:674-688.

7 Mangine R.E., Noyes F.R., DeMaio M. Minimal protection program: advanced weight bearing and range of motion after ACL reconstruction—weeks 1 to 5. Orthopedics. 1992;15:504-515.

8 Noyes F.R., Barber S.D., Mangine R.E. Bone–patellar ligament–bone and fascia lata allografts for reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1125-1136.

9 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S. Posterior cruciate ligament replacement with a two-strand quadriceps tendon–patellar bone autograft and a tibial inlay technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1241-1252.

10 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft in patients with articular cartilage damage. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:626-634.

11 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Arthroscopic-assisted allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients with symptomatic arthrosis. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:24-32.

12 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Posterolateral knee reconstruction with an anatomical bone–patellar tendon–bone reconstruction of the fibular collateral ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:259-273.

13 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Revision anterior cruciate surgery with use of bone–patellar tendon–bone autogenous grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1131-1143.

14 Noyes F.R., Berrios-Torres S., Barber-Westin S.D., Heckmann T.P. Prevention of permanent arthrofibrosis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction alone or combined with associated procedures: a prospective study in 443 knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:196-206.

15 Noyes F.R., DeMaio M., Mangine R.E. Evaluation-based protocols: a new approach to rehabilitation. Orthopedics. 1991;14:1383-1385.

16 Noyes F.R., Mangine R.E., Barber S. Early knee motion after open and arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:149-160.

17 Noyes F.R., Mangine R.E., Barber S.D. The early treatment of motion complications after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop. 1992;277:217-228.

18 Noyes F.R., Wojtys E.M. The early recognition, diagnosis and treatment of the patella infera syndrome. In: Tullos H.S., editor. Instructional Course Lectures. Rosemont, IL: AAOS; 1991:233-247.

19 Noyes F.R., Wojtys E.M., Marshall M.T. The early diagnosis and treatment of developmental patella infera syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1991;265:241-252.

20 Paulos L.E., Rosenberg T.D., Drawbert J., et al. Infrapatellar contracture syndrome. An unrecognized cause of knee stiffness with patella entrapment and patella infera. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:331-341.

21 Rubman M.H., Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Arthroscopic repair of meniscal tears that extend into the avascular zone. A review of 198 single and complex tears. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:87-95.