Chapter 30 Rehabilitation of Meniscus Repair and Transplantation Procedures

CLINICAL CONCEPTS

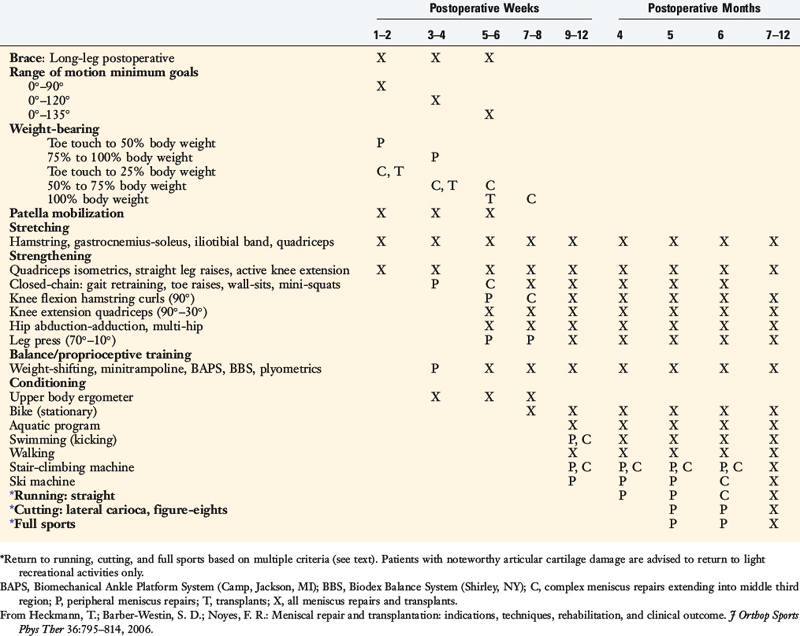

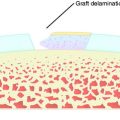

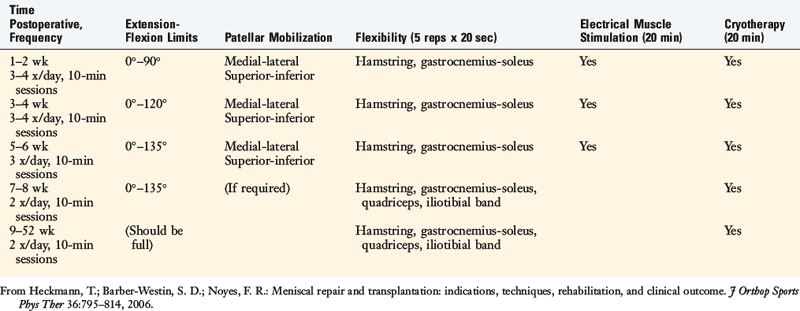

The postoperative program for meniscus repair and transplantation is shown in Table 30-1. The initial goal is to prevent excessive weight-bearing, because high compressive and shear forces can disrupt healing meniscus repair sites (especially radial repairs) and transplants. Variations are built into the protocol according to the type, location, and size of the meniscus repair and whether concomitant procedures (such as ligament reconstructions) are performed. The surgeon has the responsibility to inform the physical therapy team of details regarding the type of tear and the repair that was performed. Meniscus repairs with all-inside fixators have inferior holding strength, and commonly, only a few sutures are used. These repairs require more protection to allow for healing during the first 6 postoperative weeks. Inside-out meniscus repair techniques involve multiple vertical divergent sutures (see Chapter 28, Meniscus Tears: Diagnosis, Operative Techniques, and Clinical Outcomes) and have superior holding strength.

Clinicians should be aware that meniscus repairs located in the periphery (outer third region) heal rapidly, whereas complex repairs that extend into the central third region tend to heal more slowly and require greater caution. In addition, modifications to the postoperative exercise program may be required if noteworthy articular cartilage deterioration is found during the arthroscopic procedure. This rehabilitation program has been used at the authors’ institution in hundreds of meniscus transplant and repair recipients, and the results of clinical investigations3–5,7 demonstrate its safety and effectiveness in restoring normal knee motion, muscle, and gait characteristics.

IMMEDIATE POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Important early postoperative signs for the therapist to monitor include effusion, pain, gait, knee flexion and extension, patellar mobility, strength and control of the lower extremity, lower extremity flexibility, and tibiofemoral symptoms indicative of a meniscal tear (Table 30-2).

TABLE 30-2 Postoperative Signs and Symptoms Requiring Prompt Treatment

| Postoperative Sign and/or Symptom | Treatment Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Continued pain in the medial or lateral tibiofemoral compartment of the meniscus repair or transplant | Physician examination, assess need for refixation or re-repair |

| Tibiofemoral compartment clicking, or a subjective sensation by the patient of “something being loose” within the tibiofemoral joint | Physician examination, assess need for refixation or re-repair |

| Failure to meet knee extension and flexion goals (see text) | Overpressure program, early gentle manipulation under anesthesia if 0°–135° not met by 6 wk postoperatively |

| Decreased patellar mobility (indicative of early arthrofibrosis) | Aggressive knee flexion, extension overpressure program, or gentle manipulation under anesthesia to regain full ROM and normal patellar mobility |

| Decrease in voluntary quadriceps contraction and muscle tone, advancing muscle atrophy | Aggressive quadriceps muscle strengthening program, EMS |

| Persistent joint effusion, joint inflammation | Aspiration, rule out infection, close physician observation |

EMS, electrical muscle stimulation; ROM, range of knee motion.

From Heckmann, T.; Barber-Westin, S. D.; Noyes, F. R.: Meniscal repair and transplantation: Indications, techniques, rehabilitation, and clinical outcome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 36:795–814, 2006.

Patients present to physical therapy on the 1st day after surgery on bilateral axillary crutches in a postoperative dressing with a long-leg brace locked in full extension. The postoperative bandage and dressing are changed to allow the application of thigh-high compression stockings and a compression bandage. Early control of postoperative effusion is essential for pain management and early quadriceps reeducation. In addition to compression, cryotherapy is critical in this time period. Patients receive a commercial cooling unit, which is used six to eight times daily at home. In the clinic, the use of various cryotherapy machines provide compression simultaneously with the cold program (Fig. 30-1).

Patients are instructed to maintain lower limb elevation as frequently as possible during the 1st week. A portable neuromuscular electric stimulator may be helpful for quadriceps reeducation and pain management (Fig. 30-2). These devices are used six times per day, 15 minutes per session, until the patient displays an excellent voluntary quadriceps contraction.

The patient’s initial response to surgery and progression during the first 2 weeks sets the tone for the initial phases of the rehabilitation program. Common postoperative complications include excessive pain or swelling, quadriceps shutdown or loss of voluntary isometric contraction, range of motion (ROM) limitations, and saphenous nerve irritations for medial repairs. It is important to monitor patient complaints of posteromedial or infrapatellar burning, posteromedial tenderness along the distal pes anserine tendons, tenderness of Hunter’s canal along the medial thigh, hypersensitivity to light pressure, or hypersensitivity to temperature change. These abnormal symptoms or signs occur in early cases of complex regional pain syndrome (see Chapter 43, Diagnosis and Treatment of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome) and require immediate treatment.

BRACE AND CRUTCH SUPPORT

Critical Points BRACE AND CRUTCH SUPPORT

Brace Used 6 Wk in Complex Meniscus Repairs and Transplants

Brace not required in simple meniscus repairs in periphery (outer third region).

Crutch support for 4 wk postoperative. Patients weaned when normal gait demonstrated.

Crutches with partial weight-bearing are recommended for the first 4 wk in all cases.

Weight-bearing is gradually progressed as shown in Table 30-1, and patients are encouraged to use a normal gait that avoids a locked knee and assumes normal flexion throughout the gait cycle.

Crutches with partial weight-bearing are recommended for the first 4 weeks in all cases. Weight-bearing is gradually progressed as shown in Table 30-1, and patients are encouraged to use a normal gait that avoids a locked knee and assumes normal flexion throughout the gait cycle. Patients who had a repair of a radial meniscus tear are kept non–weight-bearing for 4 weeks to protect the repair site.

RANGE OF KNEE MOTION AND FLEXIBILITY

Passive knee flexion and passive and active/active-assisted knee extension exercises are begun the 1st day postoperatively. Active knee flexion is limited to avoid hamstring strain to the posteromedial joint. ROM exercises are performed in the seated position initially from 0° to 90°. Flexion is gradually advanced to 120° by the 3rd to 4th week and 135° by the 5th to 6th week (Table 30-3). Patients who had extensive repairs may be required to limit ROM to 0° to 90° for the first 2 weeks. Knee motion exercises are performed three to four times daily until normal motion is achieved. Hyperextension is avoided in individuals who have had anterior horn meniscus repairs.

TABLE 30-3 Range of Motion, Flexibility, and Modality Usage after Meniscus Repair and Transplantation

If 0° to 90° of knee motion is not easily achieved by the end of the 1st postoperative week, the patient may be at risk for a knee motion complication. Individuals who develop such a limitation are placed into a specific treatment program previously described in detail.2,6 Overpressure exercises are usually successful in achieving the last few degrees of extension if initiated within the first few weeks after surgery. The patient props the foot and ankle on a towel to elevate the hamstrings and gastrocnemius, which allows the knee to drop into full extension. A 10-pound weight may be added to the distal thigh and knee to stretch the posterior capsule (Fig. 30-3). This program is done for 10 minutes at a time, six to eight times per day.

Flexion exercises are performed in the seated position, using the opposite lower extremity to provide overpressure (Fig. 30-4). Chair-rolling, wall-sliding, passive quadriceps stretching, and ROM devices such as the ERMI Knee Flexionator (ERMI, Atlanta, GA) are also helpful in regaining full knee flexion. It is important that no squatting exercises are performed for at least 4 months, because this places large tensile forces on posterior meniscus repairs and transplants.

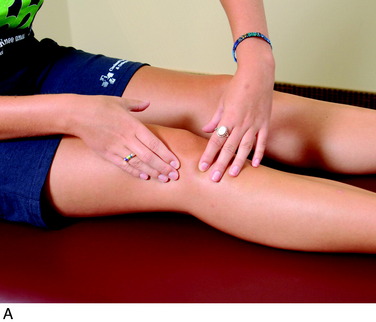

ROM exercises are accompanied by patellar mobilization (in the superior, inferior, medial, and lateral directions), which is paramount to achieve full knee motion (Fig. 30-5). Flexibility exercises, beginning with hamstring and gastrocnemius-soleus, are begun the 1st day postoperatively and are done three times per day. Quadriceps and iliotibial band flexibility exercises are incorporated at 7 to 8 weeks postoperative. Sustained static stretching is performed, with the stretch held for 30 seconds and repeated five times.

BALANCE AND PROPRIOCEPTIVE TRAINING

Balance and proprioception exercises are initiated when patients achieve partial weight-bearing, typically the 1st week after surgery. Crutches are used for support during these exercises until full weight-bearing is allowed. Initially, patients perform weight-shifting from side-to-side and front-to-back. Then, cup-walking is encouraged to develop symmetry between the surgical and the contralateral limbs, hip and knee flexion, quadriceps control during midstance, hip and pelvic control during midstance, and adequate gastrocnemius-soleus control during push-off (Fig. 30-6).

Many devices are available to assist with balance and gait retraining, including Styrofoam half rolls and whole rolls, and the Biomechanical Ankle Platform System (BAPS, Camp, Jackson, MI). Patients walk (unassisted) on Styrofoam half rolls to develop a center of balance, quadriceps control in midstance, and postural positioning. The BAPS board is used in double-leg and single-leg stance to promote proprioception. More sophisticated devices are also available (Fig. 30-7), including Biodex’s Balance System (Biodex Corporation, Shirley, NY) and Neurocom’s Balance System (Neurocom, Clackamas, OR). These devices provide visual feedback to assist with a variety of balance activities.

STRENGTHENING

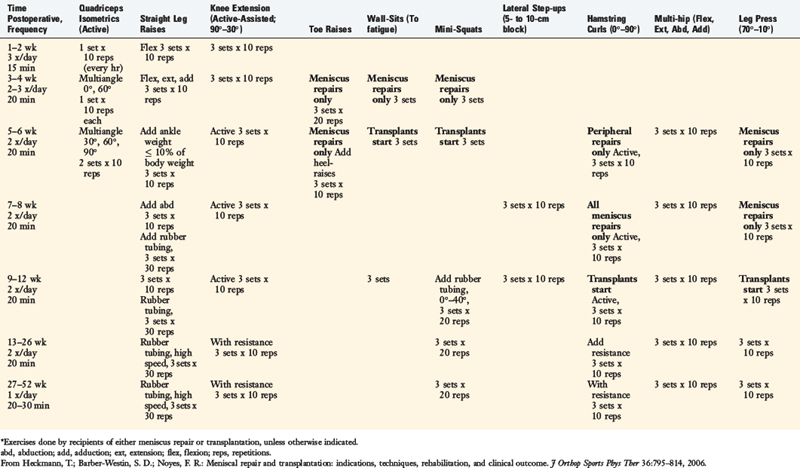

The strengthening program is begun on the 1st day postoperative with quadriceps isometrics, straight leg raises (Fig. 30-8), and active-assisted knee extension from 90° to 30° (Table 30-4). Initially, straight leg raises are performed in the flexion plane only. The patient must achieve a sufficient quadriceps contraction to eliminate an extensor lag before adding straight leg raises in the other three planes (abduction, adduction, and extension). These exercises are performed as three to five sets of 10 repetitions, and this set/repetition rule allows for systematic progression of ankle weights as tolerated.

At weeks 3 to 4, closed kinetic chain weight-bearing exercises are begun. Toe-raises for gastrocnemius-soleus strengthening, wall-sits, and mini-squats for quadriceps strengthening are added when patients are 50% weight-bearing. Wall-sits (Fig. 30-9) and mini-squats (Fig. 30-10) are begun at 5 to 6 weeks postoperative after meniscal transplantation. These activities should be limited from 0° to 60° of flexion to protect the posterior horn of the meniscus.

Open kinetic chain non–weight-bearing exercises are begun 5 to 6 weeks postoperative (see Table 30-4). Knee extension progressive resistive exercises (PREs) are initiated from 90° to 30° to protect the patellofemoral joint.1 By keeping the quadriceps exercises in this protected ROM, minimal forces will be placed along peripheral and midsubstance repair sites. Progression from ankle weights to machines occurs as the patient progresses the amount of weight in the exercise program. Quadriceps control is critical to the program progression.

CONDITIONING

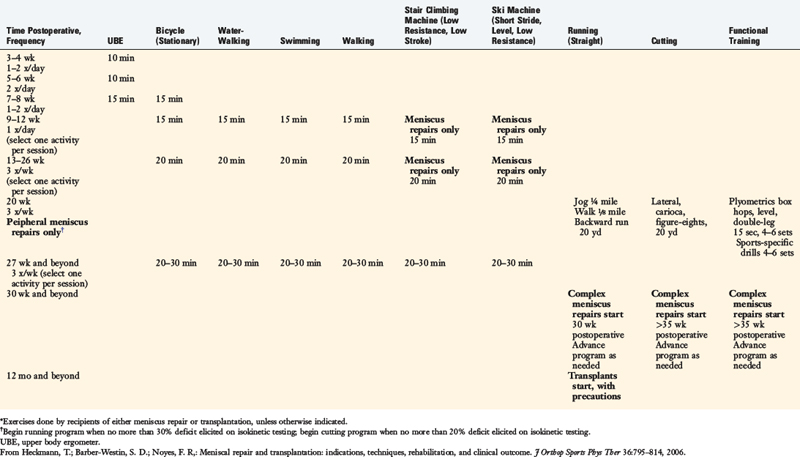

A cardiovascular program may be begun as early as 2 to 4 weeks postoperatively if the patient has access to an upper body ergometer (Table 30-5). Stationary bicycling is begun 7 to 8 weeks postoperative. The seat height is adjusted to its highest level based on patient body size, and a low-resistance level is used. A recumbent bicycle may be substituted in patients who have damage to the patellofemoral joint articular cartilage or anterior knee pain.

PLYOMETRIC TRAINING

1 Grood E.S., Suntay W.J., Noyes F.R., Butler D.L. Biomechanics of the knee-extension exercise. Effect of cutting the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:725-734.

2 Heckmann T.P., Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Autogeneic and allogeneic anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation. In: Ellenbecker T.S., editor. Knee Ligament Rehabilitation. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:132-150.

3 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Arthroscopic repair of meniscal tears extending into the avascular zone in patients younger than twenty years of age. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:589-600.

4 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Arthroscopic repair of meniscus tears extending into the avascular zone with or without anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients 40 years of age and older. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:822-829.

5 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D., Rankin M. Meniscal transplantation in symptomatic patients less than fifty years old. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1392-1404.

6 Noyes F.R., Berrios-Torres S., Barber-Westin S.D., Heckmann T.P. Prevention of permanent arthrofibrosis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction alone or combined with associated procedures: a prospective study in 443 knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:196-206.

7 Rubman M.H., Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Arthroscopic repair of meniscal tears that extend into the avascular zone. A review of 198 single and complex tears. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:87-95.