Chapter 25 Rehabilitation of Medial Ligament Injuries

CLINICAL CONCEPTS

Medial ligament injuries are among the most frequently treated problems of the knee joint. Whereas isolated superficial medial collateral ligament (SMCL) ruptures are common, concomitant damage to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) occurs in many cases, especially in young and active patients.1–4,9 The majority of isolated acute injuries that involve damage to the SMCL alone, or to the SMCL and posteromedial capsule (PMC), do not require surgery. Patients who have medial ligament tears classified as first degree (tear involving a few fibers), second degree (partial tear, no instability, ≤3 mm of increased medial joint opening), or third degree (complete rupture) who demonstrate either a mild to moderate increase in medial joint opening at 30° of flexion and no increase at 0° do not require acute medial ligament reconstruction. These knees are treated with the conservative rehabilitation program, and if concomitant injury exists to other ligaments, the decision of whether to reconstruct those structures is based on the extent of the injury, patient goals, and other issues addressed for the ACL in Chapter 7, Anterior Cruciate Ligament Primary and Revision Reconstruction: Diagnosis, Operative Techniques, and Clinical Outcomes, the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) in Chapter 21, Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Diagnosis, Operative Techniques, and Clinical Outcomes, and the posterolateral ligament structures in Chapter 22, Posterolateral Ligament Injuries: Diagnosis, Operative Techniques, and Clinical Outcomes.

An acute third-degree injury consisting of gross major disruption of all of the medial structures (SMCL, deep medial collateral ligament, meniscus attachments, PMC, posterior oblique ligament [POL], and semimembranosus attachments), either alone or in combination with cruciate ligament tears, often require surgical intervention. In these knees, large increases in medial joint opening are present at 30° of flexion, and at least 5 mm of increased medial joint opening exists at 0°. In addition, repair of medial meniscus attachments is indicated to retain meniscus function. Chronic deficiency of the medial ligament structures that causes partial giving-way during athletic activities may require reconstruction. In these knees, partial or complete ACL deficiency is frequently noted. The indications for medial ligament surgery and the appropriate candidates are discussed in detail in Chapter 24, Medial and Posteromedial Ligament Injuries: Diagnosis, Operative Techniques, and Clinical Outcomes.

CONSERVATIVE TREATMENT OF MEDIAL LIGAMENT INJURIES

The goals of rehabilitation of medial ligament injuries are to

Provide appropriate protection initially after the injury to allow the disrupted medial ligament structures to “stick-down” and heal with the least amount of residual ligament elongation or abnormal medial joint opening.

Provide appropriate protection initially after the injury to allow the disrupted medial ligament structures to “stick-down” and heal with the least amount of residual ligament elongation or abnormal medial joint opening. Regain normal proprioception, balance, coordination, and neuromuscular control for desired activities.

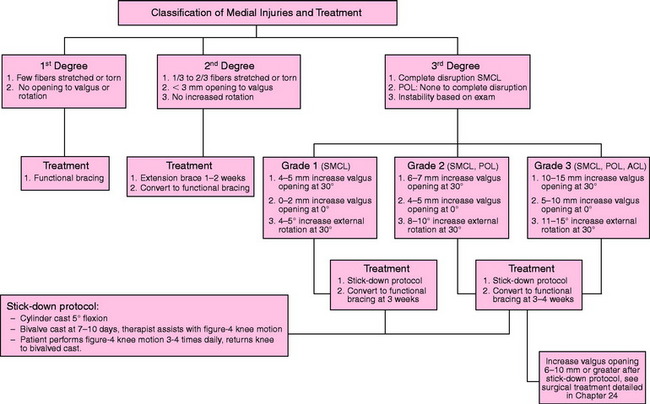

Regain normal proprioception, balance, coordination, and neuromuscular control for desired activities.The treatment rationale for patients with acute medial ligament ruptures is shown in Figure 25-1. The algorithm is divided into three major sections based on the extent of injury to the SMCL and PMC/POL. The first- and second-degree injuries are treated initially with a functional brace, weight-bearing as tolerated, and the rehabilitation program summarized in Tables 25-1 and 25-2. Some second-degree injuries may have considerable medial pain and swelling, and in these cases, an extension brace and assistive ambulatory devices are used for the initial 1 to 2 weeks after the injury. The type of functional brace varies from a medial/lateral hinge elastic type to a long-leg postoperative brace in select cases in which more support is required.

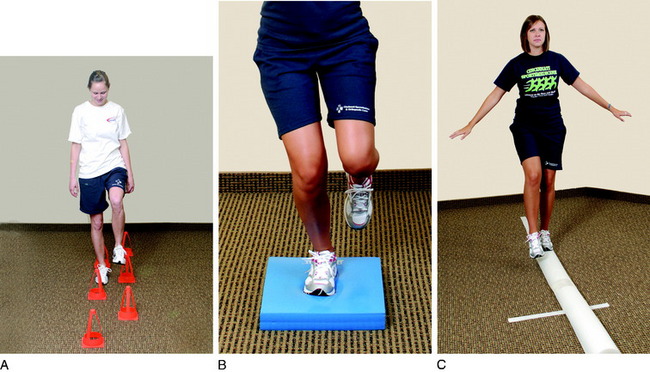

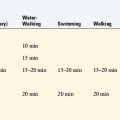

Table 25-1 Conservative Management of First-Degree Medial Ligament Injuries

ROM, range of motion.

Table 25-2 Conservative Management of Second-Degree Medial Ligament Injuries

ROM, range of motion.

Third-Degree Injuries: Weeks 1 to 3

At 7 to 10 days, the cylinder cast is split into an anterior and a posterior shell (Fig. 25-2) to permit the patient to begin passive range of motion (ROM) exercises, which are initially assisted by the therapist. The cast is used for an additional 2 weeks to allow for early stick-down of the medial ligament structures. The patient is allowed to bear 25% of her or his body weight as long as the cast is in place. ROM exercises are initiated in a figure-four position from 0° to 90° in order to avoid valgus and external rotation loads on the healing ligaments (Fig. 25-3). A 4-inch tubular stocking is double-wrapped around the foot and ankle to allow the patient under her or his own power to flex the knee. This protected ROM program is performed three to four times a day for 10 to 15 minutes per session. Quadriceps strengthening exercises including isometrics and flexion straight leg raises are emphasized. TheraBand resistance for plantar flexion is used to maintain gastrocnemius tone. Ice, compression, and elevation are used for pain and swelling control.

Critical Points CONSERVATIVE TREATMENT OF MEDIAL LIGAMENT INJURIES

Third-Degree Injuries: Weeks 4 to 6

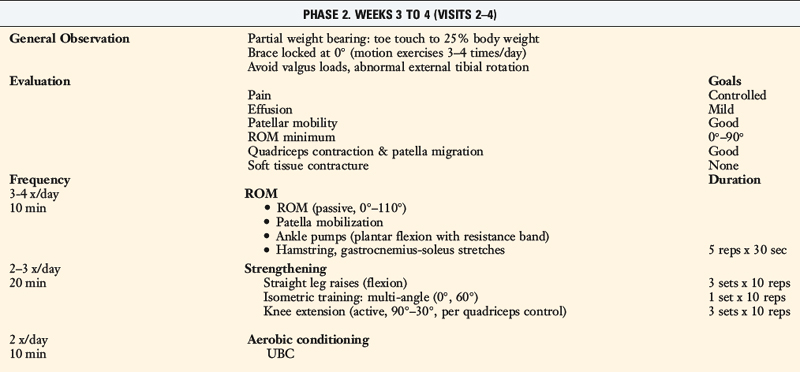

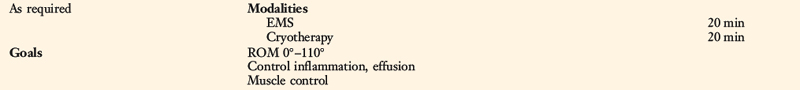

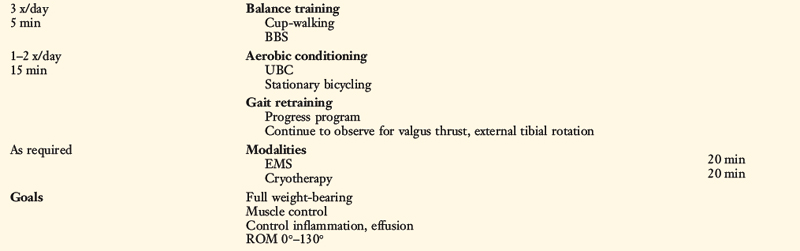

Emphasis during this time period focuses on ligament protection during gait and exercise. The progression of exercise allows knee motion to be restored within normal limits. Muscle strengthening includes both closed-chain and table exercises (straight leg raises). Emphasis is placed on hip and core control plus progression of quadriceps strengthening (Table 25-3).

Third-Degree Injuries: Weeks 7 to 9

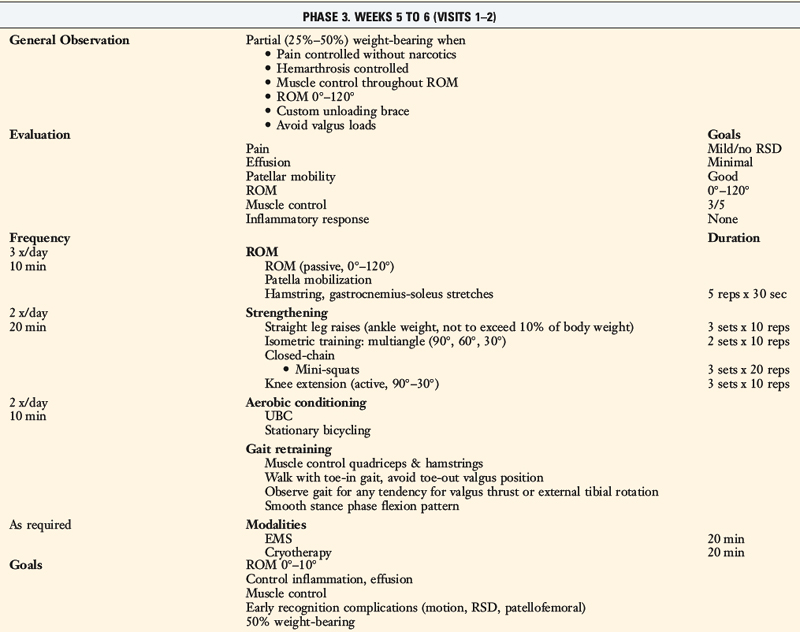

If a long-leg brace was used in the previous phase, a functional brace is now initiated. Patients who already have a functional brace maintain its usage for ambulation. Gait and ROM should be normal or nearly normal, with restoration to normal as soon as possible. Pain and swelling should be within normal limits. Emphasis during this phase of treatment is on returning lower extremity strength to normal and to begin cross-training for cardiovascular endurance. Balance and proprioception exercises are also important components of this phase (see Chapter 13, Rehabilitation of Primary and Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions).

Third-Degree Injuries: Weeks 10 to 12

The focus of this final phase is on return to activity. By this time period, gait, ROM, activities of daily living, and symptoms should be within normal limits. The exercise progression advocates return of isokinetic muscle strength parameters within 70% and 90% for straight-ahead running and more strenuous turning/cutting drills, respectively. The cross-training program is advanced to a full running program that then allows for sports-specific training. Distance and direction-specific running and agility drills are incorporated. Heavy strength training occurs on opposite days of the running program. Injury prevention and neuromuscular retraining programs include jump-training activities with emphasis on technique, position, alignment, and repetition as discussed in detail in Chapter 19, Decreasing the Risk of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Female Athletes. Isokinetic testing is performed, with the goal of achieving a 90% bilateral comparison for quadriceps and hamstrings torque–to–body weight ratios (corrected for age and gender), and a hamstring-to-quadriceps ratio of 60% at 120°/sec. Patients continue brace use for activity only. Follow-up treatment is based on the need for symptom control and/or functional progression for unrestricted return to activity.

Concomitant Cruciate Ligament Injuries

Patients who have a concomitant PCL rupture and medial ligament rupture also undergo the initial stick-down program with a posterior calf pad to prevent posterior tibial subluxation. The cast is used for 4 weeks, followed with a long-leg brace with a posterior pad, which is used for 4 weeks. Then, weight-bearing, range of knee motion, and quadriceps exercises are progressed. Figure-four ROM exercises with an anterior drawer support allow for protection of both ligaments. The initial knee motion goal is 0° to 90°, which is then gradually progressed to full 6 weeks after cast wear. Full weight-bearing is permitted after 6 weeks, with emphasis on quadriceps control. Hamstrings contractions are not allowed for the initial 6 weeks and are then permitted in the active mode only for an additional 6 weeks. The patient’s gait, knee motion, quadriceps control, and symptoms should be back to normal limits in order to consider surgical intervention. Knee injuries with combined third-degree medial ligament ruptures and PCL ruptures often require operative repair; the postoperative course is described in Chapter 23, Rehabilitation of Posterior Cruciate Ligament and Posterolateral Reconstructive Procedures.

POSTOPERATIVE REHABILITATION OF MEDIAL LIGAMENT REPAIRS/RECONSTRUCTIONS

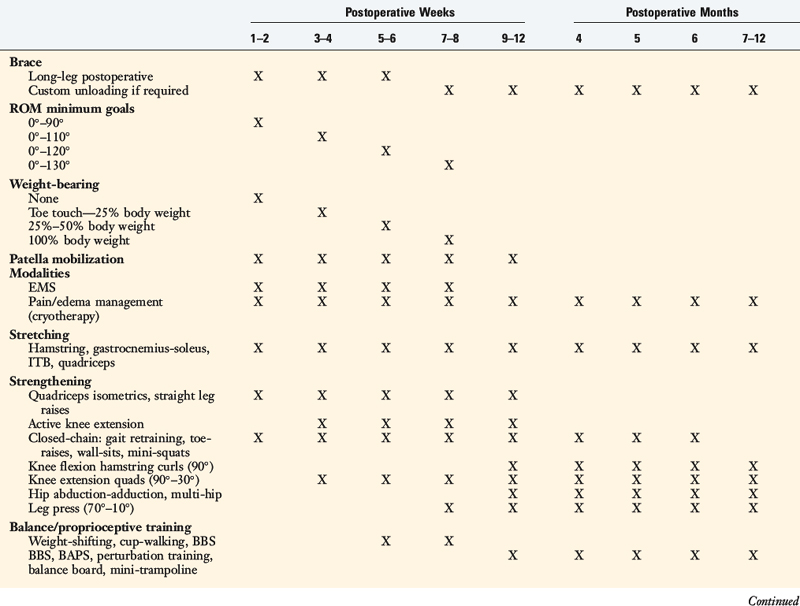

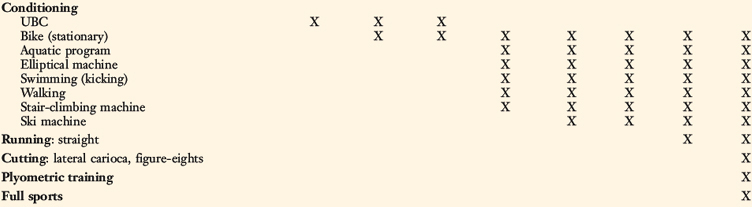

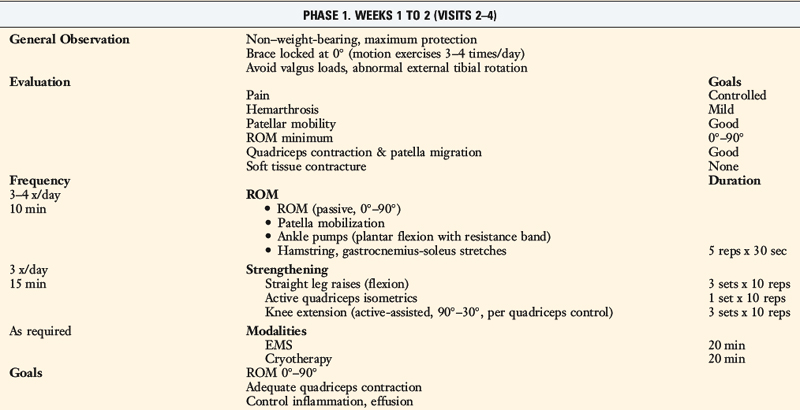

The surgical treatment of acute third-degree medial ligament ruptures involves anatomic repair to restore continuity and function, including repair of the medial meniscus attachments. Knees with chronic deficiency of the medial ligament ruptures often require a graft reconstruction using a semitendinosus-gracilis autograft or allograft, discussed in Chapter 24, Medial and Posteromedial Ligament Injuries: Diagnosis, Operative Techniques, and Clinical Outcomes. The operative procedure is designed to provide sufficient tensile strength to the reconstructed medial tissues to allow immediate knee motion and restore early limb function. The goal is to provide 4 weeks of maximum protection, using a long-leg postoperative brace. After this period, the rehabilitation program progresses, as soft tissue healing provides sufficient strength for ambulatory activities.

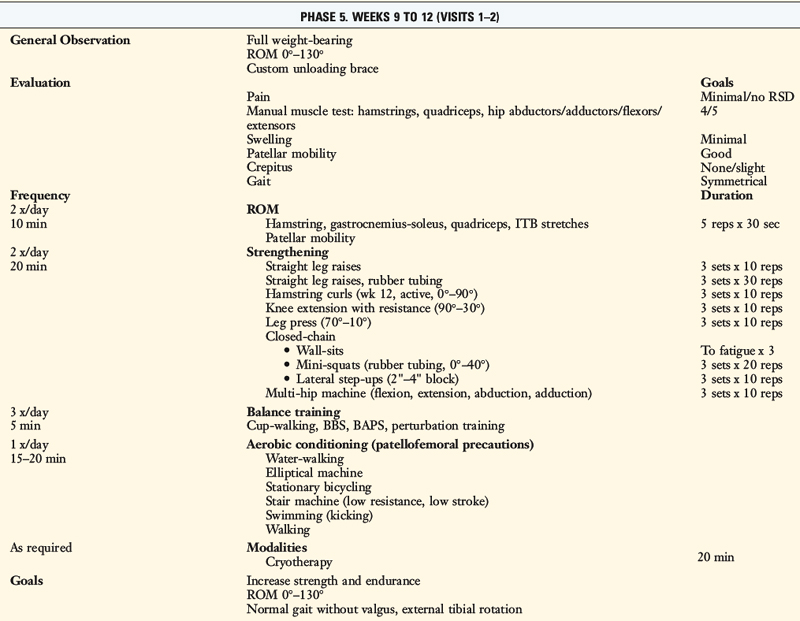

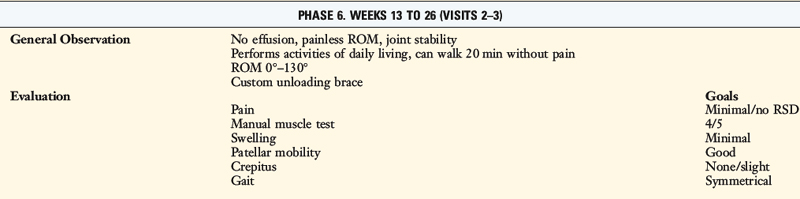

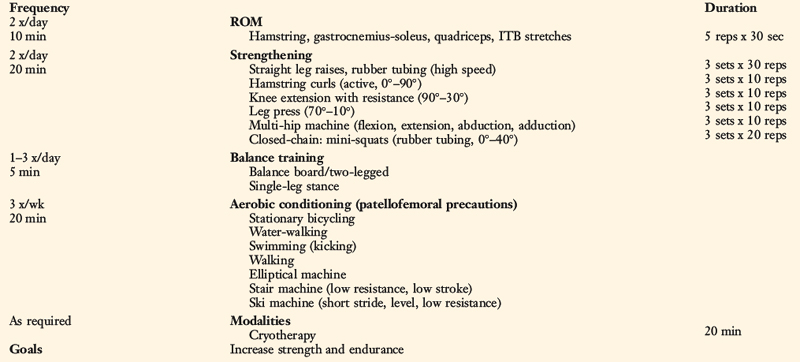

The postoperative protocol (see Table 25-3) is divided into seven phases according to the time period postoperatively (e.g., phase I comprises postoperative wk 1–2). Each phase has four main categories that describe the factors evaluated by the therapist and exercises performed by the patient:

Critical Points POSTOPERATIVE REHABILITATION OF MEDIAL LIGAMENT REPAIRS/RECONSTRUCTIONS

Range of Knee Motion

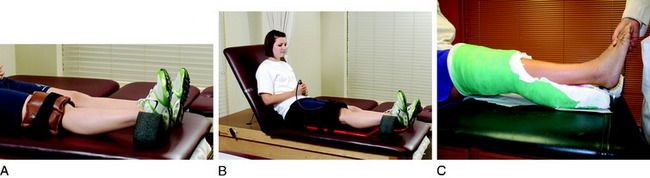

The goal in the 1st postoperative week is to obtain 0° to 90°. A continuous passive motion machine is not required. Patients perform passive and active ROM exercises in a seated position for 10 minutes a session, approximately four to six times per day. Initially, the therapist performs this exercise by applying a mild amount of varus and internal tibial rotation stress during flexion to unload the medial compartment (Fig. 25-4). Full passive knee extension must be obtained immediately to avoid excessive scarring in the intercondylar notch and posterior capsular tissues. It is important to note that patients undergoing SMCL repair or reconstruction are at an increased risk for developing a knee motion problem postoperatively.5 Supervision and close monitoring of the patient’s progress by the therapist is essential to avoid a potential arthrofibrotic response. If the patient has difficulty regaining at least 0° by the 7th postoperative day, an overpressure program is begun as described in detail in Chapter 13, Rehabilitation of Primary and Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction, and 41, Prevention and Treatment of Knee Arthrosis. Overpressure exercises and modalities include hanging weight, extension board, and a drop-out cast (Fig. 25-5).

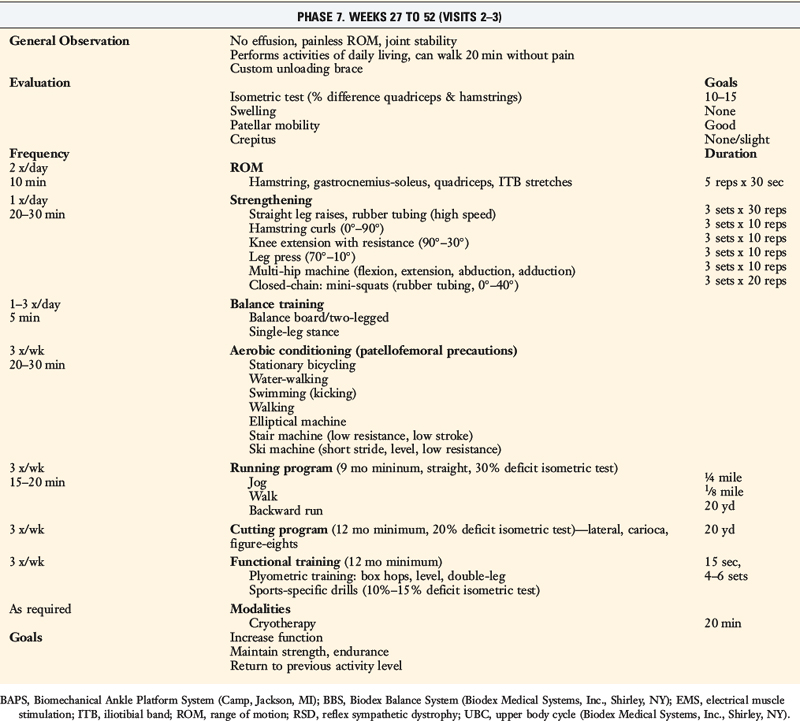

Figure 25-5 Extension overpressure exercises. A, Hanging weight. B, Extension board. C, Drop-out cast.

Knee flexion is gradually increased to 130° by the 7th to 8th postoperative week. Passive knee flexion exercises are performed initially in the figure-four position. Other methods to assist in achieving flexion include chair-rolling, wall-slides, commercial devices (Fig. 25-6), and passive quadriceps stretching exercises.

Patellar Mobilization

Maintaining normal patellar mobility is critical to regain a normal range of knee motion. The loss of patellar mobility is often associated with arthrofibrosis and, in extreme cases, the development of patella infera.6–8 Patellar glides are performed beginning the 1st postoperative day in all four planes (superior, inferior, medial, and lateral) with sustained pressure applied to the appropriate patellar border for at least 10 seconds (Fig. 25-7). This exercise is performed for 5 minutes before ROM exercises. Caution is warranted if an extensor lag is detected, because this may be associated with poor superior migration of the patella, indicating the need for additional emphasis on this exercise. Patellar mobilization is performed for approximately 12 weeks postoperatively.

Strengthening

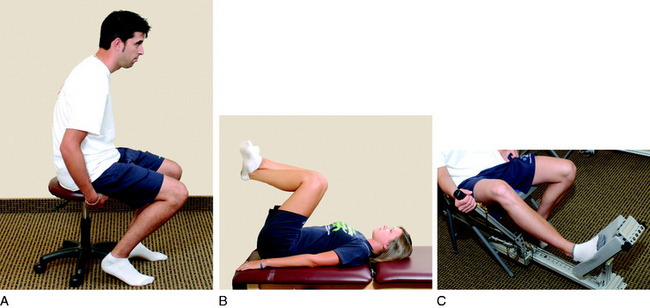

Closed kinetic chain exercises are begun when partial weight-bearing of at least 50% is tolerated. Patients are instructed to avoid valgus loading during these exercises. These activities initially consist of mini-squats from 0° to 45°, toe-raises, and wall-sits. During the wall-sitting exercise, the patient may squeeze a ball between the distal thighs, inducing a hip adduction contraction and a stronger VMO contraction, or hold dumbbell weights in his or her hands to increase body weight (Fig. 25-8). The patient can also shift his or her body weight over the involved side to stimulate a single-leg contraction. The wall-sitting position should be held to a maximum burning of the quadriceps and repeated. This is an excellent exercise to mimic a stationary leg-press, achieve quadriceps muscle fiber recruitment, and induce muscle fatigue to build strength.

Balance, Proprioceptive, and Perturbation Training

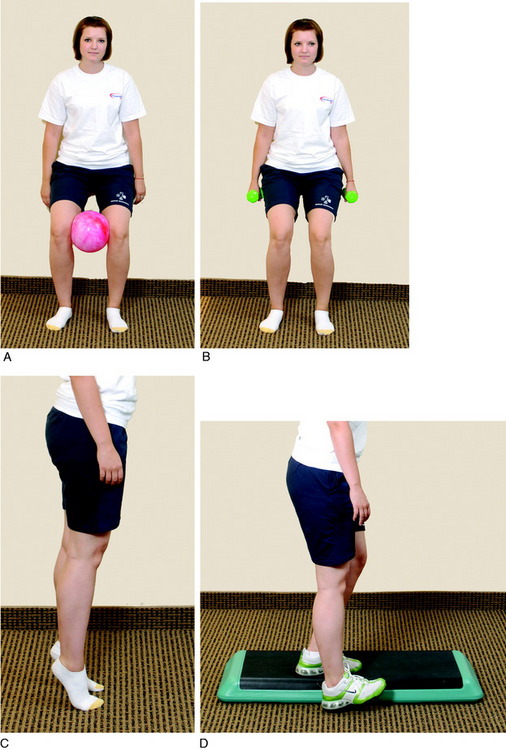

Balance and proprioceptive training are initiated when the patient achieves 50% weight-bearing. Initially, the patient stands and shifts weight from side-to-side and front-to-back. This activity promotes confidence in the leg’s ability to withstand the pressures of weight-bearing and initiates the stimulus to knee joint position sense. Cup walking is begun when the patient achieves full weight-bearing to promote symmetry between the surgical and the uninvolved limbs (Fig. 25-9).

Running and Agility Program

The running program is based on the patient’s athletic goals, particularly the position or physical requirements of the activity, and is described in detail in Chapter 13, Rehabilitation of Primary and Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions. The program is performed three times per week, on opposite days of the strength program. Because the running program may not reach aerobic levels initially, a cross-training program is used to facilitate cardiovascular fitness. The cross-training program is performed on the same day as the strength workout.

Plyometric Training

During the various jumps, the patient is instructed to keep his or her body weight on the balls of the feet. He or she should jump and land with the knees flexed and shoulder-width apart to avoid knee hyperextension and an overall valgus lower limb position. The patient should understand that the exercises are reaction and agility drills, and although speed is emphasized, correct body posture must be maintained throughout the drills. This program is described in detail in Chapter 13, Rehabilitation of Primary Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions.

1 Deibert M.C., Aronsson D.D., Johnson R.J., et al. Skiing injuries in children, adolescents, and adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:25-32.

2 Fetto J.F., Marshall J.L. Medial collateral ligament injuries of the knee: a rationale for treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;132:206-218.

3 Halinen J., Lindahl J., Hirvensalo E., Santavirta S. Operative and nonoperative treatments of medial collateral ligament rupture with early anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective randomized study. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1134-1140.

4 Najibi S., Albright J.P. The use of knee braces, part 1: prophylactic knee braces in contact sports. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:602-611.

5 Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. The treatment of acute combined ruptures of the anterior cruciate and medial ligaments of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:380-389.

6 Noyes F.R., Wojtys E.M. The early recognition, diagnosis and treatment of the patella infera syndrome. In: Tullos H.S., editor. Instructional Course Lectures. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; 1991:233-247.

7 Noyes F.R., Wojtys E.M., Marshall M.T. The early diagnosis and treatment of developmental patella infera syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1991;265:241-252.

8 Paulos L.E., Rosenberg T.D., Drawbert J., et al. Infrapatellar contracture syndrome. An unrecognized cause of knee stiffness with patella entrapment and patella infera. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:331-341.

9 Peterson L., Junge A., Chomiak J., et al. Incidence of football injuries and complaints in different age groups and skill-level groups. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(5 suppl):S51-S57.