Chapter 79 Regional Anesthesia for Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Is It Worth the Effort?

Regional anesthesia (RA) for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been associated with numerous benefits compared with general anesthesia (GA). Regional anesthesia can afford both dense surgical anesthesia and long-lasting, opioid-sparing, postoperative analgesia with a low rate of serious complications.1–7 Regional anesthesia techniques for THA and TKA include, either alone or in combination, central neuraxial blockade (CNB) (i.e., epidural and spinal anesthesia) and peripheral nerve blockade (PNB). For example, combined spinal-epidural is an excellent technique for THA or TKA because it combines the benefits of spinal and epidural blockade, that is, reliable rapid-onset dense surgical anesthesia provided by the intrathecal dose of local anesthetic and the flexibility to administer supplemental local anesthetic as necessary via the epidural catheter for prolonged intraoperative anesthesia or postoperative analgesia, or both. Alternatively, PNB avoids many of the unwanted adverse effects of both GA and CNB, such as hypotension, nausea and vomiting, and pruritus, and allows for targeted unilateral blockade of the operative limb providing excellent analgesia.8,9 Continuous PNB (CPNB) for TKA has gained tremendous popularity in recent years10,11 because continuous perineural infusions of dilute, long-acting local anesthetic solution via an indwelling catheter can significantly prolong postoperative analgesia compared with single-injection techniques12,13 and, importantly, can facilitate rehabilitation14–17 because opioid-related adverse effects are spared.9,18, 19

Despite the benefits of regional anesthesia for THA and TKA, many orthopedic surgeons have been reluctant to embrace regional anesthesia because of concerns of operating room delay and block failure.20 Indeed, GA affords a near 100% success rate in comparison with regional anesthesia, which carries an inherent failure rate even in experienced hands.21 GA can often be performed faster than regional anesthesia, and the technical skills needed to administer GA are easier to acquire than regional anesthesia. Furthermore, the choice of anesthetic technique—regional anesthesia versus GA—is oftentimes influenced by time constraints, the availability of a “block room,”22 skilled anesthetic personnel, and perceived liability risk.23 These obstacles have prompted many orthopedic surgeons (and anesthesiologists alike) to ask: “Is regional anesthesia worth the effort?”

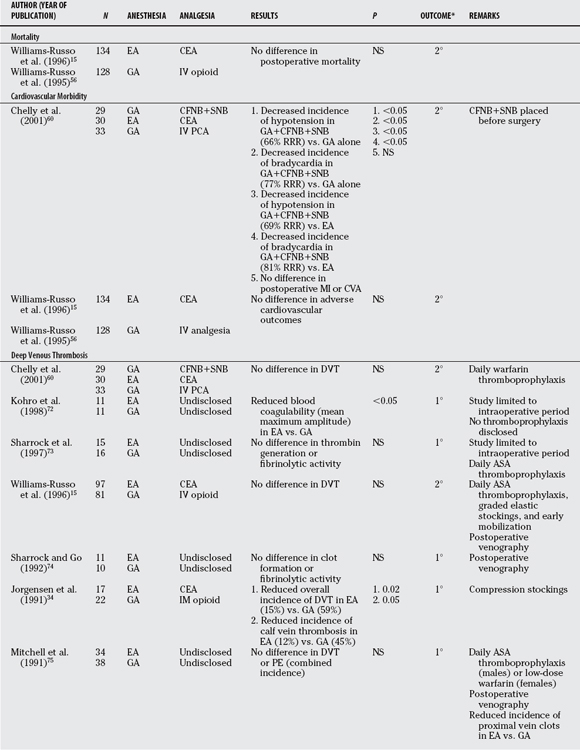

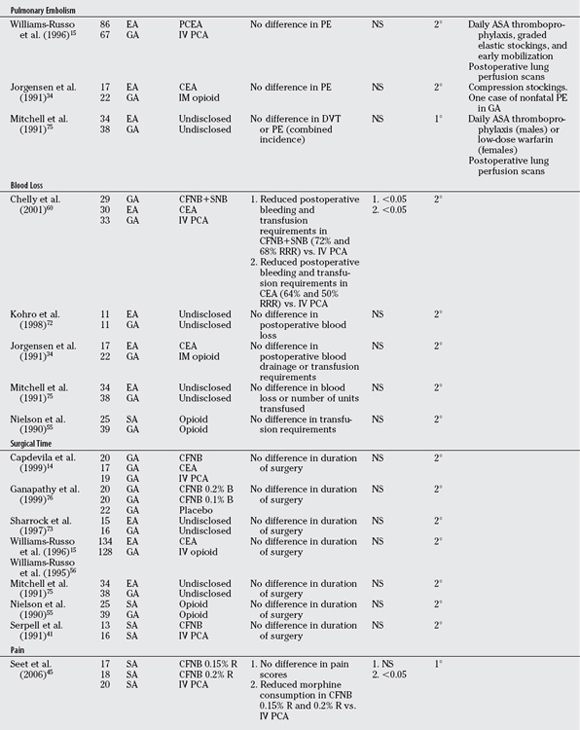

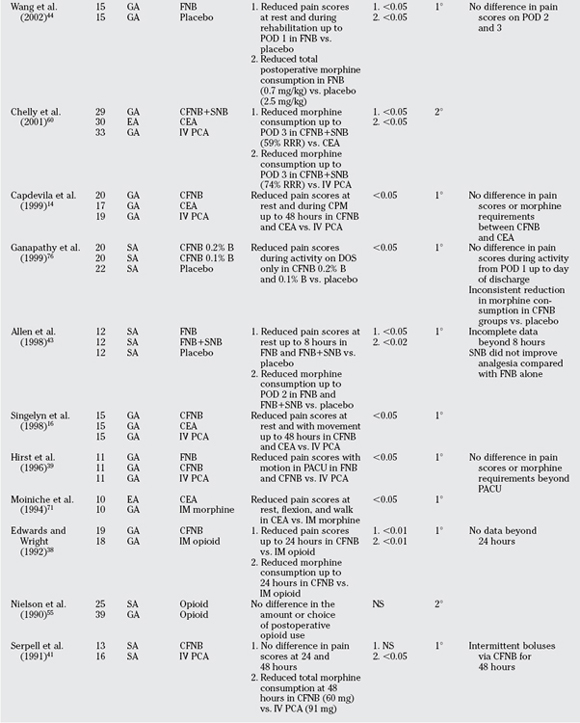

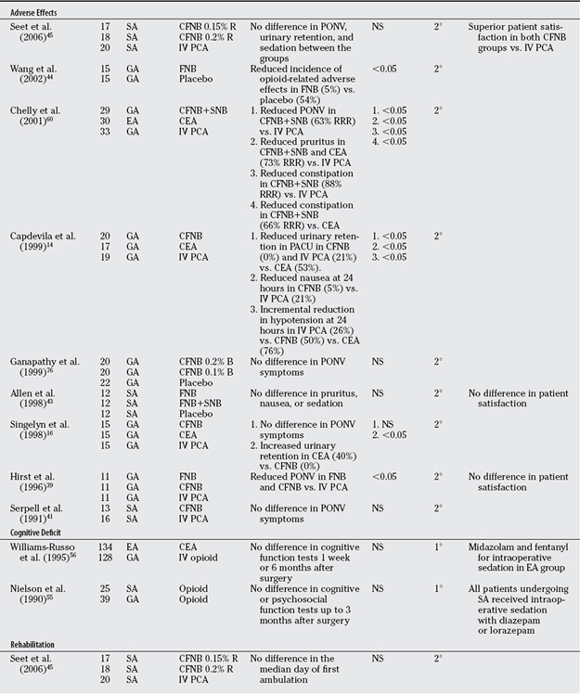

Numerous recent meta-analyses have addressed the question of regional anesthesia versus GA for major orthopedic surgery with conflicting results.24–29 Much of the source data for these meta-analyses are dated because databases such as MEDLINE capture indexed articles published as early as 1950. These older studies do not reflect advances in training, anesthetic techniques, and perioperative surgical practices, such as routine low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis and standardized clinical pathways. Moreover, meta-analyses are notoriously limited by the inclusion of studies with small sample sizes, heterogeneity between source studies, publication bias, informed censoring, and meta-analyst bias.30,31 Accordingly, results of meta-analyses oftentimes do not reflect those of corresponding large, randomized, controlled trials (RCTs).32 In this chapter, we review and summarize (Tables 79-1 and 79-2) the best contemporary data available regarding the effects of anesthetic technique, either regional anesthesia or GA, on important perioperative outcomes for patients undergoing THA or TKA. We included RCTs of adult patients who underwent regional anesthesia or GA for THA or TKA that were published in English from 1990 to July 2007. We included trials that compared a regional anesthesia technique for primary surgical anesthesia or postoperative analgesia, or both, with conventional GA for surgery and/or systemic analgesia for postoperative pain control.

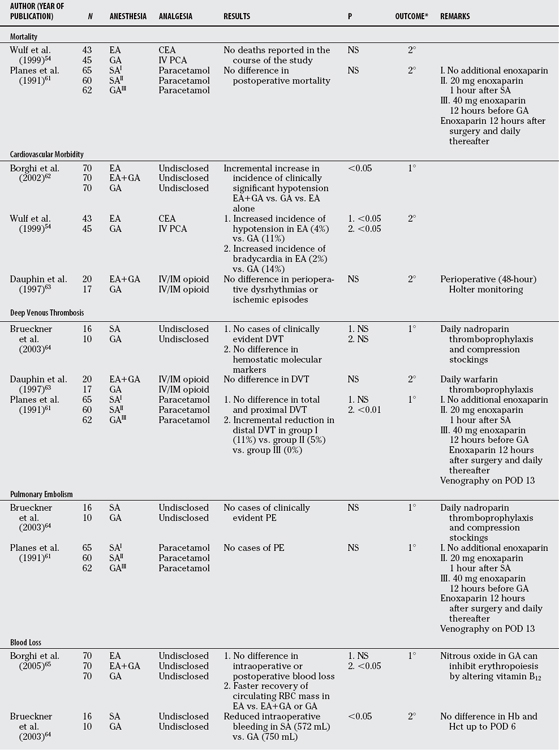

TABLE 79-1 Perioperative Outcomes after Regional Anesthesia versus General Anesthesia for Total Hip Arthroplasty

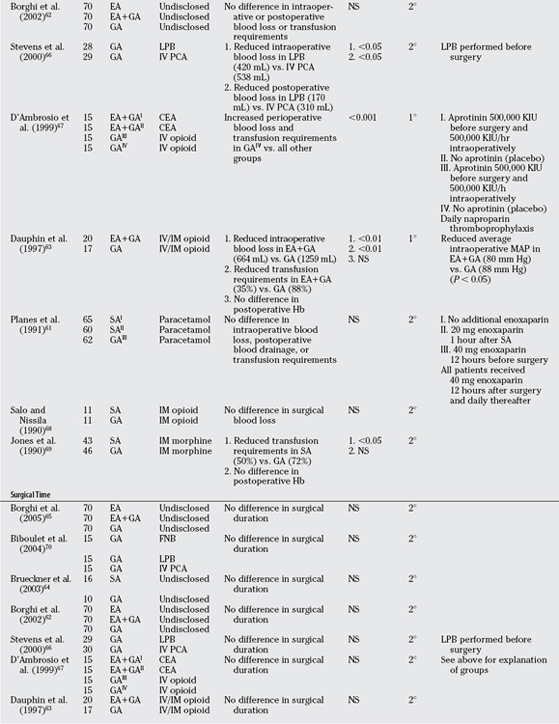

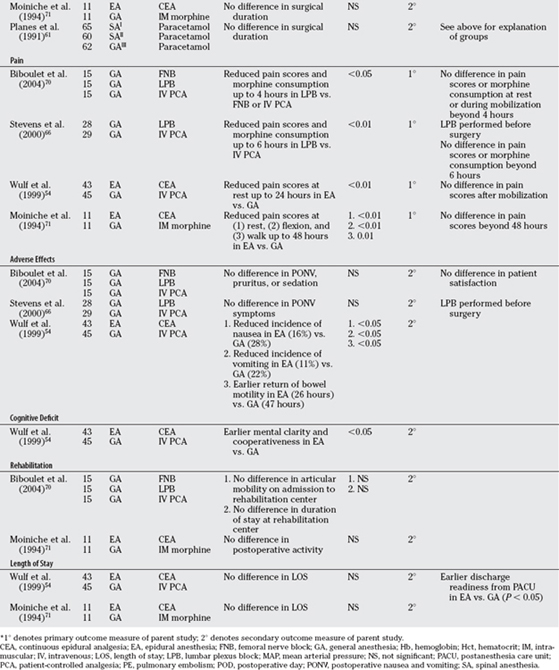

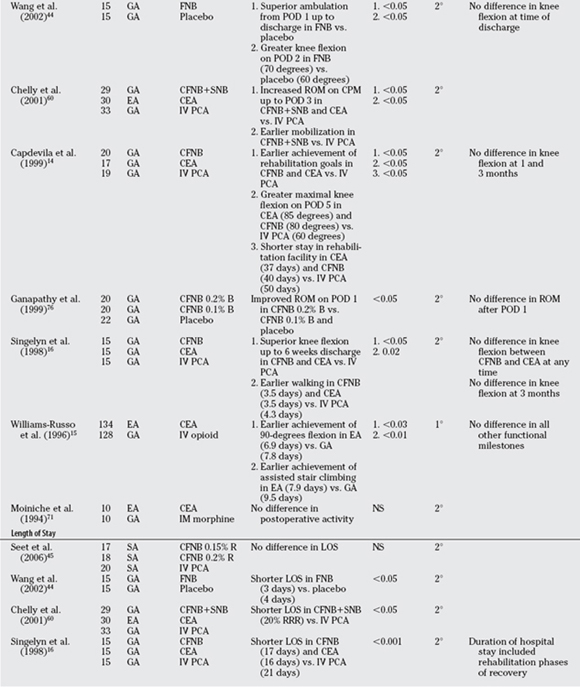

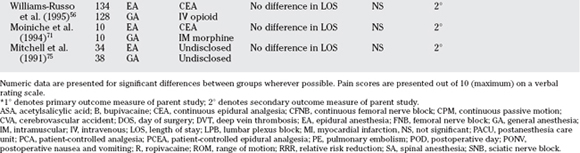

TABLE 79-2 Perioperative Outcomes after Regional Anesthesia versus General Anesthesia for Total Knee Arthroplasty

MORTALITY

No contemporary RCTs are designed primarily to assess differences in mortality after regional anesthesia versus GA for THA or TKA. Because death is such a rare occurrence in modern anesthetic practice, prohibitively large numbers of patients would be required for study to determine the effects of anesthetic technique on patient mortality. In a widely cited meta-analysis of 141 clinical trials (almost 10,000 patients in total) comparing CNB or GA for a variety of surgery types (mostly orthopedic), Rodgers and colleagues25 found that overall mortality was reduced by one third (odds ratio [OR], 0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54–0.90) in patients allocated to CNB. Furthermore, Rodgers and colleagues25 demonstrated that overall mortality was reduced regardless of whether neuraxial blockade was continued after surgery.25 For epidural analgesia after THA, Wu and colleagues26 similarly found no reduction in mortality compared with systemic analgesia after reviewing a random sample of 23,136 patients from a national Medicare claims database between 1994 and 1999. It may be that any observed reduction in mortality conferred by regional anesthesia is due to the surgical anesthetic rather than postoperative analgesia.

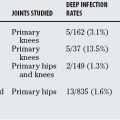

DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS AND PULMONARY EMBOLISM

It has long been thought that CNB can decrease the incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) rates by enhancing lower extremity venous blood flow,33 and perhaps “washing out” the thrombogenic load accumulated during surgery. In addition, epidural analgesia and CPNB each facilitate postoperative rehabilitation after THA and TKA,14–16 which may indirectly prevent DVT formation. Mauermann and colleagues28 reported a meta-analysis of 10 studies examining the incidences of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients randomized to CNB or GA for THA. The pooled data revealed a significantly lower risk for DVT (OR, 0.27; 95% CI, 0.17–0.42) and PE (OR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.12–0.56) for patients who received CNB in comparison with those who received GA.

Importantly, among the 10 RCTs included in Mauermann and colleagues’28 meta-analysis, 8 were carried out before 1990 when routine thromboprophylaxis was not commonplace. In only 1 of these 10 trials did patients receive heparin thromboprophylaxis. However, after the introduction of routine thromboprophylaxis, there appears to be no significant difference in the incidence of DVT and PE for patients undergoing THA (see Table 79-1). For TKA, only two studies21,34 currently reviewed showed a decreased incidence of DVT in favor of regional anesthesia, and these without chemical thromboprophylaxis. Furthermore, none of the TKA studies indicated that the incidence of PE is affected by anesthetic technique (see Table 79-2). It therefore remains questionable whether regional anesthesia offers any additive effect in reducing DVT and PE when used in combination with modern routine thromboprophylaxis.

BLOOD LOSS

In a meta-analysis investigating the effects of CNB on surgical blood loss, Joanne Guay35 found that CNB for THA significantly reduced the likelihood of transfusion by three fourths (OR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.11–0.53). Peripheral vasodilation most likely accounts for any observed blood-sparing effects of CNB for THA. By contrast, however, we found conflicting results in the contemporary literature for intraoperative bleeding and transfusion requirements in patients receiving regional anesthesia either alone or in combination with GA for THA (see Table 79-1). For TKA, the contemporary literature demonstrates no significant difference in intraoperative blood loss with regional anesthesia compared with GA, and this lack of effect is most likely due to the use of an intraoperative tourniquet.

DURATION OF SURGERY

Mauermann and colleagues’28 meta-analysis demonstrated a modest, but significant, decrease in surgical time with CNB compared with GA for THA. This difference may be a reflection of the reduction in bleeding afforded by CNB and, by extension, a “drier” operative field. Among the studies currently reviewed, the duration of surgery was not influenced by the type of anesthetic for THA or TKA (see Tables 79-1 and 79-2). However, none of these studies considered the total operating room time that includes anesthetic intervention. Endless efforts to improve operating room efficiency have spawned modifications of how anesthetic services are delivered, such as the introduction of a “block room” or anesthesia induction room where regional techniques are performed before operating room entry. These models have been shown to reduce the anesthesia-related operating room time when compared with GA22,36 and may prove cost-saving in the future.37

PAIN

Choi and colleagues’24 meta-analysis examines the efficacy of postoperative lumbar epidural analgesia compared with systemic analgesia after THA or TKA. These authors hesitantly conclude that epidural analgesia affords superior pain relief for up to 6 hours after surgery compared with conventional systemic analgesia. One important limitation of this meta-analysis is that all patients, whether THA or TKA, were analyzed in aggregate despite important differences between these surgical procedures, especially concerning the severity of postoperative pain.

Our review identified only four recently published RCTs that investigated regional anesthesia versus systemic analgesia for THA (see Table 79-1). It appears that the analgesic benefit of regional anesthesia is short-lived and does not confer extended benefit once the local anesthetic recedes or the infusion ceased. However, in one THA study, there was a significant reduction in morphine consumption beyond the expected duration of action of the local anesthetic, possibly suggesting a pre-emptive analgesic effect of regional anesthesia. For TKA, epidural analgesia, single-injection femoral nerve block (FNB), and continuous catheter-based FNB can each improve postoperative pain control compared with systemic analgesia (see Table 79-2).14,15,38–45 Only one study included a comparison of single-injection FNB with continuous catheter-based FNB (CFNB) for postoperative analgesia after TKA and showed little additional benefit by the placement of a catheter as opposed to the single-injection technique,39 but this finding has since been countered.13,17 Furthermore, a study comparing CFNB with intravenous (IV) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) for TKA revealed an opioid-sparing effect, which is a surrogate marker of pain relief, and better patient satisfaction scores favoring CFNB to IV PCA, despite no significant differences in reported pain scores between the groups.45 Lastly, whether sciatic afferents (i.e., posterior aspect of the knee) contribute significan-tly to pain after TKA remains a subject of controversy.43,46–48

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Opioid-related adverse effects, especially nausea and vomiting, are of primary concern to patients49 and can delay discharge from hospital.50 In many published studies examining regional anesthesia versus GA, including most examined herein, significant differences in opioid-related adverse effects were observed in favor of regional anesthesia. Unfortunately, however, opioid-related adverse effects are almost never designated as primary outcome measures. Reported “significant” differences in secondary outcomes must be interpreted with caution because the parent studies are often inadequately powered to detect such differences.51 For example, in Seet and colleagues’45 RCT, there was a significant opioid-sparing effect in patients receiving regional anesthesia compared with IV PCA, but no significant difference in opioid-related adverse effects such as PONV and sedation.45 For this reason, each listed outcome in Tables 79-1 and 79-2 is identified as the primary or secondary outcome measure of the corresponding parent study.

COGNITIVE DEFICIT

It has long been suggested that regional anesthesia allows for rapid recovery of cognitive function after surgery compared with GA.52,53 In our review of the contemporary literature, we found only one recent RCT that reported cognitive performance after regional anesthesia versus GA for THA with results in favor of regional anesthesia (see Table 79-1).54 By contrast, two robust studies demonstrated no difference in short- and long-term cognitive function between regional anesthesia and GA for patients with TKA (see Table 79-2), but IV sedation was administered to the regional anesthesia groups, which can introduce bias.55,56

REHABILITATION AND LENGTH OF STAY

Regional anesthesia can significantly hasten postoperative rehabilitation and shorten length of stay in hospital after TKA, but not after THA (see Tables 79-1 and 79-2). This difference is likely because the severity of pain decreases rapidly after THA in comparison with TKA, where pain can often be severe, and exacerbates with physical therapy. Epidural analgesia and CFNB for TKA can each significantly improve rehabilitation and help to attain milestones earlier than IV PCA.8 CFNB is generally preferred over epidural analgesia because important unwanted effects such as bilateral blockade, hypotension, bradycardia, and nausea and vomiting are avoided,14,16, 57 whereas the patient’s anticoagulation status is less of a concern.58,59 A shorter length of stay in hospital has consistently been demonstrated in patients receiving CFNB or FNB for pain relief after TKA.16,44, 60 Remarkably, the early rehabilitation achievements facilitated by regional anesthesia for TKA can translate into shorter patient stays in rehabilitation centers after discharge from hospital.14

SUMMARY

In modern anesthetic practice, both GA and regional anesthesia can be reliably performed for THA and TKA with high success and few major complications. Contemporary evidence strongly suggests that regional anesthesia techniques, especially PNB, can provide superior early postoperative analgesia and decrease opioid consumption compared with traditional systemic analgesia after THA or TKA. Accordingly, fair evidence has been reported to suggest that regional anesthesia minimizes opioid-related adverse effects. For TKA, the analgesic benefits of regional anesthesia can afford superior rehabilitation or earlier hospital discharge, but the same is not true for THA. By contrast, regional anesthesia techniques may reduce blood loss and transfusion requirements after THA, but not TKA. Finally, in the current environment of routine thromboprophylaxis and standardized clinical pathways, regional anesthesia techniques do not appear to decrease the incidence of DVT and PE, preserve cognitive function, or reduce the duration of surgery compared with GA for THA or TKA. Table 79-3 provides a summary of recommendations based on leveis of evidence for primary outcome measures.77,78

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | (REFERENCES) |

|---|---|---|

| When compared with GA: | THA | TKA |

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; GA, general anesthesia; PE, pulmonary embolism; RA, regional anesthesia; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

1 Aromaa U, Lahdensuu M, Cozanitis DA. Severe complications associated with epidural and spinal anaesthesias in Finland 1987-1993. A study based on patient insurance claims. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:445-452.

2 Auroy Y, Narchi P, Messiah A, et al. Serious complications related to regional anesthesia: Results of a prospective survey in France. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:479-486.

3 Borgeat A, Ekatodramis G, Kalberer F, Benz C. Acute and nonacute complications associated with interscalene block and shoulder surgery: A prospective study. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:875-880.

4 Fanelli G, Casati A, Garancini P, Torri G. Nerve stimulator and multiple injection technique for upper and lower limb blockade: Failure rate, patient acceptance, and neurologic complications. Study Group on Regional Anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:847-852.

5 Moen V, Dahlgren N, Irestedt L. Severe neurological complications after central neuraxial blockades in Sweden 1990-1999. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:950-959.

6 Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L, et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1274-1280.

7 Brull R, McCartney CJ, Chan VW, El Beheiry H. Neurological complications after regional anesthesia: Contemporary estimates of risk. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:965-974.

8 Davies AF, Segar EP, Murdoch J, et al. Epidural infusion or combined femoral and sciatic nerve blocks as perioperative analgesia for knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93:368-374.

9 Zaric D, Boysen K, Christiansen C, et al. A comparison of epidural analgesia with combined continuous femoral-sciatic nerve blocks after total knee replacement. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1240-1246.

10 Hebl JR, Kopp SL, Ali MH, et al. A comprehensive anesthesia protocol that emphasizes peripheral nerve blockade for total knee and total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(suppl 2):63-70.

11 Pagnano MW, Hebl J, Horlocker T. Assuring a painless total hip arthroplasty: A multimodal approach emphasizing peripheral nerve blocks. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:80-84.

12 Boezaart AP. Perineural infusion of local anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:872-880.

13 Salinas FV, Liu SS, Mulroy MF. The effect of single-injection femoral nerve block versus continuous femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty on hospital length of stay and long-term functional recovery within an established clinical pathway. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1234-1239.

14 Capdevila X, Barthelet Y, Biboulet P, et al. Effects of perioperative analgesic technique on the surgical outcome and duration of rehabilitation after major knee surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:8-15.

15 Williams-Russo P, Sharrock NE, Haas SB, et al. Randomized trial of epidural versus general anesthesia: Outcomes after primary total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996:199-208.

16 Singelyn FJ, Deyaert M, Joris D, et al. Effects of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, continuous epidural analgesia, and continuous three-in-one block on postoperative pain and knee rehabilitation after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:88-92.

17 Watson MW, Mitra D, McLintock TC, Grant SA. Continuous versus single-injection lumbar plexus blocks: Comparison of the effects on morphine use and early recovery after total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:541-547.

18 Richman JM, Liu SS, Courpas G, et al. Does continuous peripheral nerve block provide superior pain control to opioids? A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:248-257.

19 Brull R, Sharrock NE. Anesthesia for knee surgery. In: Insall JN, Scott WN, editors. Surgery of the Knee. 4th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2006:1064-1073.

20 Oldman M, McCartney CJ, Leung A, et al. A survey of orthopedic surgeons’ attitudes and knowledge regarding regional anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1486-1490.

21 Nielsen KC, Steele SM. Outcome after regional anaesthesia in the ambulatory setting—is it really worth it? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002;16:145-157.

22 Armstrong KP, Cherry RA. Brachial plexus anesthesia compared to general anesthesia when a block room is available. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:41-44.

23 Katz J. A survey of anesthetic choice among anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 1973;52:373-375.

24 Choi PT, Bhandari M, Scott J, Douketis J. Epidural analgesia for pain relief following hip or knee replacement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD003071.

25 Rodgers A, Walker N, Schug S, et al. Reduction of postoperative mortality and morbidity with epidural or spinal anaesthesia: Results from overview of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:1493.

26 Wu CL, Hurley RW, Anderson GF, et al. Effect of postoperative epidural analgesia on morbidity and mortality following surgery in medicare patients. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:525-533.

27 Block BM, Liu SS, Rowlingson AJ, et al. Efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;290:2455-2463.

28 Mauermann WJ, Shilling AM, Zuo Z. A comparison of neuraxial block versus general anesthesia for elective total hip replacement: A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1018-1025.

29 Urwin SC, Parker MJ, Griffiths R. General versus regional anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:450-455.

30 Higgins MS, Stiff JL. Pitfalls in performing meta-analysis: I. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:405.

31 McKenzie PJ. Pitfalls in performing meta-analysis: II. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:406-408.

32 LeLorier J, Gregoire G, Benhaddad A, et al. Discrepancies between meta-analyses and subsequent large randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:536-542.

33 Modig J, Malmberg P, Karlstrom G. Effect of epidural versus general anaesthesia on calf blood flow. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1980;24:305-309.

34 Jorgensen LN, Rasmussen LS, Nielsen PT, et al. Antithrombotic efficacy of continuous extradural analgesia after knee replacement. Br J Anaesth. 1991;66:8-12.

35 Guay J. The effect of neuraxial blocks on surgical blood loss and blood transfusion requirements: A meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:124-128.

36 Williams BA, Kentor ML, Williams JP, et al. Process analysis in outpatient knee surgery: Effects of regional and general anesthesia on anesthesia-controlled time. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:529-538.

37 Williams BA, Kentor ML, Vogt MT, et al. Economics of nerve block pain management after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Potential hospital cost savings via associated postanesthesia care unit bypass and same-day discharge. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:697-706.

38 Edwards ND, Wright EM. Continuous low-dose 3-in-1 nerve blockade for postoperative pain relief after total knee replacement. Anesth Analg. 1992;75:265-267.

39 Hirst GC, Lang SA, Dust WN, et al. Femoral nerve block. Single injection versus continuous infusion for total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth. 1996;21:292-297.

40 Raj PP, Knarr DC, Vigdorth E, et al. Comparison of continuous epidural infusion of a local anesthetic and administration of systemic narcotics in the management of pain after total knee replacement surgery. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:401-406.

41 Serpell MG, Millar FA, Thomson MF. Comparison of lumbar plexus block versus conventional opioid analgesia after total knee replacement. Anaesthesia. 1991;46:275-277.

42 Weller R, Rosenblum M, Conard P, Gross JB. Comparison of epidural and patient-controlled intravenous morphine following joint replacement surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:582-586.

43 Allen HW, Liu SS, Ware PD, et al. Peripheral nerve blocks improve analgesia after total knee replacement surgery. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:93-97.

44 Wang H, Boctor B, Verner J. The effect of single-injection femoral nerve block on rehabilitation and length of hospital stay after total knee replacement. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:139-144.

45 Seet E, Leong WL, Yeo AS, Fook-Chong S. Effectiveness of 3-in-1 continuous femoral block of differing concentrations compared to patient controlled intravenous morphine for post total knee arthroplasty analgesia and knee rehabilitation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34:25-30.

46 Pham DC, Gautheron E, Guilley J, et al. The value of adding sciatic block to continuous femoral block for analgesia after total knee replacement. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:128-133.

47 Cook P, Stevens J, Gaudron C. Comparing the effects of femoral nerve block versus femoral and sciatic nerve block on pain and opiate consumption after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:583-586.

48 Morin AM, Kratz CD, Eberhart LH, et al. Postoperative analgesia and functional recovery after total-knee replacement: Comparison of a continuous posterior lumbar plexus (psoas compartment) block, a continuous femoral nerve block, and the combination of a continuous femoral and sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:434-445.

49 Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:652-658.

50 Pavlin DJ, Rapp SE, Polissar NL, et al. Factors affecting discharge time in adult outpatients. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:816-826.

51 Mariano ER, Ilfeld BM, Neal JM. “Going fishing”-the practice of reporting secondary outcomes as separate studies. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:183-185.

52 Sharrock NE, Fischer G, Goss S, et al. The early recovery of cognitive function after total-hip replacement under hypotensive epidural anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:123-127.

53 Tzabar Y, Asbury AJ, Millar K. Cognitive failures after general anaesthesia for day-case surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:194-197.

54 Wulf H, Biscoping J, Beland B, et al. Ropivacaine epidural anesthesia and analgesia versus general anesthesia and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine in the perioperative management of hip replacement. Ropivacaine Hip Replacement Multicenter Study Group. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:111-116.

55 Nielson WR, Gelb AW, Casey JE, et al. Long-term cognitive and social sequelae of general versus regional anesthesia during arthroplasty in the elderly. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:1103-1109.

56 Williams-Russo P, Sharrock NE, Mattis S, et al. Cognitive effects after epidural vs general anesthesia in older adults. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1995;274:44-50.

57 Barrington MJ, Olive D, Low K, et al. Continuous femoral nerve blockade or epidural analgesia after total knee replacement: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1824-1829.

58 Hantler C, Despotis GJ, Sinha R, Chelly JE. Guidelines and alternatives for neuraxial anesthesia and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in major orthopedic surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:1004-1016.

59 Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Benzon H, et al. Regional anesthesia in the anticoagulated patient: Defining the risks (the second ASRA Consensus Conference on Neuraxial Anesthesia and Anticoagulation). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:172-197.

60 Chelly JE, Greger J, Gebhard R, et al. Continuous femoral blocks improve recovery and outcome of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:436-445.

61 Planes A, Vochelle N, Fagola M, et al. Prevention of deep vein thrombosis after total hip replacement. The effect of low-molecular-weight heparin with spinal and general anaesthesia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:418-422.

62 Borghi B, Casati A, Iuorio S, et al. Frequency of hypotension and bradycardia during general anesthesia, epidural anesthesia, or integrated epidural-general anesthesia for total hip replacement. J Clin Anesth. 2002;14:102-106.

63 Dauphin A, Raymer KE, Stanton EB, Fuller HD. Comparison of general anesthesia with and without lumbar epidural for total hip arthroplasty: Effects of epidural block on hip arthroplasty. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:200-203.

64 Brueckner S, Reinke U, Roth-Isigkeit A, et al. Comparison of general and spinal anesthesia and their influence on hemostatic markers in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. J Clin Anesth. 2003;15:433-440.

65 Borghi B, Casati A, Iuorio S, et al. Effect of different anesthesia techniques on red blood cell endogenous recovery in hip arthroplasty. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:96-101.

66 Stevens RD, Van Gessel E, Flory N, et al. Lumbar plexus block reduces pain and blood loss associated with total hip arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:115-121.

67 D’Ambrosio A, Borghi B, Damato A, et al. Reducing perioperative blood loss in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Int J Artif Organs. 1999;22:47-51.

68 Salo M, Nissila M. Cell-mediated and humoral immune responses to total hip replacement under spinal or general anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34:241-248.

69 Jones MJ, Piggott SE, Vaughan RS, et al. Cognitive and functional competence after anaesthesia in patients aged over 60: Controlled trial of general and regional anaesthesia for elective hip or knee replacement. BMJ. 1990;300:1683-1687.

70 Biboulet P, Morau D, Aubas P, et al. Postoperative analgesia after total-hip arthroplasty: Comparison of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine and single injection of femoral nerve or psoas compartment block. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:102-109.

71 Moiniche S, Hjortso NC, Hansen BL, et al. The effect of balanced analgesia on early convalescence after major orthopaedic surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994;38:328-335.

72 Kohro S, Yamakage M, Arakawa J, et al. Surgical/tourniquet pain accelerates blood coagulability but not fibrinolysis. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:460-463.

73 Sharrock NE, Go G, Williams-Russo P, et al. Comparison of extradural and general anaesthesia on the fibrinolytic response to total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:29-34.

74 Sharrock NE, Go G. Fibrinolytic activity following total knee arthroplasty under epidural or general anesthesia. Reg Anesth. 1992;17:94.

75 Mitchell D, Friedman RJ, Baker JDIII, et al. Prevention of thromboembolic disease following total knee arthroplasty. Epidural versus general anesthesia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991:109-112.

76 Ganapathy S, Wasserman RA, Watson JT, et al. Modified continuous femoral three-in-one block for postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1197-1202.

77 Wright JG, Swiontkowski MF, Heckman JD. Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1-3.

78 Wright JG. A practical guide to assigning levels of evidence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1128-1130.