Problem 11 Reflux in a 35-year-old man

The patient has already tried increasing the dosage of his PPI, but to no effect.

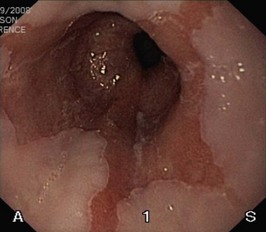

You are concerned by his anaemia and arrange for him to undergo an urgent upper GI endoscopy. (Remember, in iron deficient anaemia, if the upper GI endoscopy is normal, a colonoscopy may be indicated.) The view in Figure 11.1 shows the lower oesophagus.

Answers

A.1 Dyspepsia or reflux disease.

Several methods have been developed to test for the presence of H. pylori.

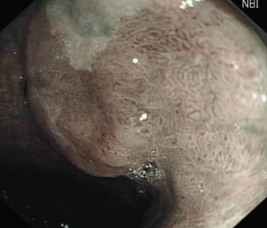

A.10 Without further treatment the nodular lesion will likely progress to invasive carcinoma. Further management is therefore concerned with removing the diseased area. In this scenario, this could involve either a local resection or undertaking an oesophagectomy. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) allows localized removal of the abnormal area (Figure 11.2). Saline or adrenaline is injected into the submucosal layer to elevate the abnormal mucosal segment. A suction cap is then applied and cautery is used to remove the abnormal nodule. The specimen is sent for histological evaluation to ensure complete resection. This option is favourable in terms of morbidity and potential mortality that is associated with oesophagectomy. However, in some patients the option of oesophagectomy may be preferred if there are multiple areas of high-grade dysplasia, there is invasion into the submucosa on the EMR specimen, or the suspicion of invasive carcinoma with nodal involvement is high.

Revision Points

Issues to Consider

Grant A.M., Wileman S.M., Ramsay C.R., et al. Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: UK collaborative randomised trial, and the REFLUX Trial Group. British Medical Journal, 337. 2008: a2664.

, www.asge.org. The website of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy includes guidelines on Barrett’s oesophagus and the management of the patient with dysphagia

, www.bsg.org.uk. The website of the British Society of Gastroenterology, including guideline for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s columnar-lined oesophagus

, www.gerd.com. A pharmaceutical company sponsored website covering all aspects of reflux disease

, www.nice.org.uk. Guideline for the management of dyspepsia, 2004

, www.sign.ac.uk. Guideline 87 – Management of oesophageal and gastric cancer, 2006