Reflexes

What is reflex testing?

Reflex testing, commonly referred to as a tendon jerk, involves evaluating the response of the phasic component of the stretch reflex pathway (S2.13). The test is referred to as a tendon reflex because a sharp stretch applied to the tendon by the therapist produces a corresponding stretch in most or all of the stretch receptors (muscle spindles) within the muscle itself. The result is temporal summation of the excitatory action potentials (S2.6) at the alpha motor neuron, which leads to a muscle contraction.

Why do I need to assess reflexes?

Assessing reflexes can give the therapist important information related to:

Reflexic properties of the muscle

Hyper-reflexia

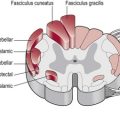

A brisk response to testing is termed an exaggerated reflex or hyper-reflexia and is one of the positive signs of spasticity (S3.21). Hyper-reflexia is considered to be a consequence of reduced descending inhibition from the cerebral cortex and in particular is associated with damage to the cortico-reticulospinal pathway (Rathore et al. 2002). The presentation of hyper-reflexia therefore implies a lesion of the central nervous system (CNS) and is cause for concern in disorders where CNS damage would not be initially suspected.

Hypo-reflexia

A diminished response to testing is termed hypo-reflexia and may be observed in pathologies affecting either the central or peripheral nervous system. More specifically it can relate to a lesion of one or more components of the reflex arc, the modulating descending systems or the muscle itself (Kandel et al. 2000).

How do I assess reflexes?

Tendon jerk

Therapist

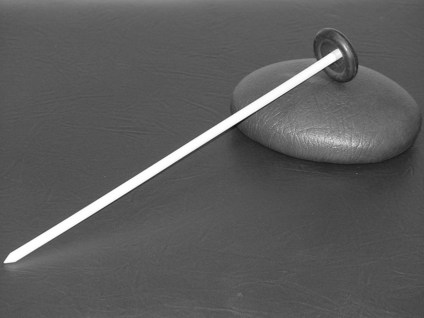

1. Reflexes are assessed using a reflex hammer (Fig. 22.1).

Figure 22.1 The reflex hammer.

2. Palpate the tendon to be tested to establish the point of contact for the reflex hammer.

3. The hammer is held loosely with the handle uppermost allowing momentum to swing the hammer freely.

4. The head of the hammer is then used gently to apply a stretch to the tendon of the relevant muscle.

a. The patient’s arm should be flexed at the elbow with the palm down

Figure 22.2 Tendon jerk testing for biceps.

b. Place a thumb or finger firmly on the biceps tendon

a. Support the upper arm in a position of 90° abduction. Then let the patient’s forearm hang free

Figure 22.3 Tendon jerk testing for triceps.

b. Strike the triceps tendon above the elbow with the hammer

Quadriceps (L2, L3, L5) (Fig. 22.4)

a. Have the patient sit or lie down with the knee relaxed and flexed

Figure 22.4 Tendon jerk testing for quadriceps femoris.

Does the muscle being tested respond at all? Yes, the neural pathway and muscle are intact for the spinal root levels indicated. For example, an appropriate response from biceps indicates that levels C5,6 are intact. If there is no response, then a lesion involving the neural pathway at the same levels should be suspected.

How does the muscle respond? A response greater than 2 indicates hyper-reflexia and therefore it may be wise to look for other signs of spasticity (e.g. hypertonia). A diminished response indicates hypo-reflexia.

Plantar response (Babinski sign) (Fig. 22.6)

Therapist

1. Using the end of a reflex hammer

2. Draw the end upwards along the lateral border of the foot

3. At the base of the 5th toe move medially across the ball of the foot (Fig. 22.6)

4. This is performed in a continuous movement and at a fairly quick speed

5. Note the movement of the toes

6. A normal response is flexion (withdrawal). Extension of the big toe with fanning of the other toes is abnormal. This is referred to as a positive Babinski sign and is indicative of a lesion of the central nervous system.

Analysis

It is important to remember that the findings from reflex testing need to be considered alongside other assessment findings. For example, in pathologies affecting the peripheral nervous system analysis should be in conjunction with results from the assessments of myotomes (S3.31) and dermatomes (S3.24). In pathologies affecting the central nervous system analysis may be in conjunction with findings related to the assessment of muscle tone (S3.21).

References and Further Reading

Kandel, ER, Schwartz, JH, Jessell, TM. Principles of neural science, ed 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

Petty, NJ. Neuromusculoskeletal examination and assessment: a handbook for therapists. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

Rathore, SS, Hinn, AR, Cooper, LS, et al. Characterization of incident stroke signs and symptoms: findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Stroke. 2002; 33:2718–2721.