Chapter 27 Recurrent urinary tract infection

AETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is by simplest definition an infection that affects any part of the urinary tract, including the kidneys, ureters, bladder and urethra. Most infections will involve the lower tract, which includes the urethra and the bladder. UTIs are most commonly caused by the organism Escherichia coli.1 Infections typically develop when bacteria or viruses enter the urinary system through the urethra. Once inside the bladder, the bacteria begin multiplying until their numbers are large enough to cause infectious symptoms (usually more than 100,000 organisms per mL in a midstream urine sample). Infections may cause swelling of the urethra (urethritis), bladder (cystitis), epididymis (epididymitis) or one or both testicles (orchitis).1 Females are far more likely to present with UTIs than males, as the female urethra is closer to the anus (and its bacterial load) than the male urethra. Most UTIs are classified as ‘uncomplicated’, being caused by a transient infection of a single strain of proliferative bacteria.2 Other cases, however, are classed as ‘complicated’ and are caused by urinary tract dysfunction or disease, or via an overarching medical condition such as diabetes. In the latter case concern exists in regard to potential renal damage; medical referral is advised.

Common symptoms associated with UTI include urgency to urinate, a burning sensation during micturition, haematuria, cloudy or foul (or otherwise abnormal) smelling urine, and frequently passing small amounts of urine.1,3 Symptoms suggestive of urethritis include a burning sensation during micturition and, in men, penile discharge. Symptoms suggestive of cystitis may include pelvic pressure, lower abdominal pain and painful and frequent urination.1,3 Symptoms suggestive of epididymitis in men include scrotal pain; tenderness in the testes and groin; painful intercourse, ejaculation and urination; and orchitis.1,3

Screening of asymptomatic women has shown that approximately 5% will have some form of UTI, 11% of women will experience UTI in any given year and 50% of women will experience symptoms of cystitis at some stage in their life.4,5 All males who present with a UTI should be referred for investigation to exclude any underlying abnormality such as prostatitis. The differential diagnoses of vaginitis or vulvovaginal infections (such as Candida spp.) are also often associated with vaginal discharge.1

RISK FACTORS

Sexual intercourse frequency is the strongest risk factor for UTIs in younger populations.1 Exposure to spermicide and new sexual partners are additive risk factors.6 Diabetes is also a risk factor for UTIs, particularly for complicated UTIs, and women who require medical management for this condition will run roughly twice the risk of developing a UTI than non-diabetic women.7 Low levels of oestrogen can dramatically change the microflora from one dominated by Lactobacillus to one dominated by E. coli, therefore increasing the risk of UTI (it should be noted that this may be of clinical relevance only in postmenopausal women).8

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Conventional treatment of UTIs relies on antibiotic therapy, and in most cases of uncomplicated infection can be managed easily, with antibiotic treatment expected to cure 80–90% of uncomplicated UTIs.5 Optimal treatment also includes adjuvant recommendations such as increasing fluid intake, encouraging complete bladder emptying and urinary alkalinisation for severe dysuria.5 Simple analgesics such as paracetamol are recommended for pain. Recurrent UTIs are usually defined as three or more UTIs in a 12-month period, and in these women a larger focus on preventive treatment is advised, even as far as prophylactic antibiotic use after sexual intercourse.5

KEY TREATMENT PROTOCOLS

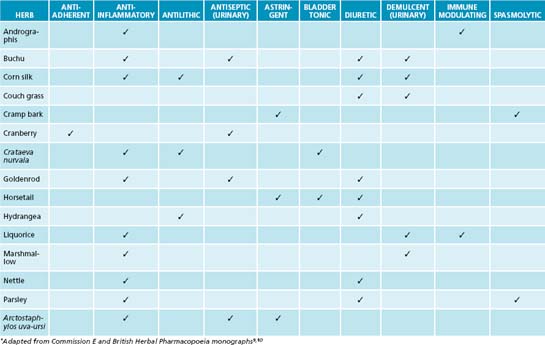

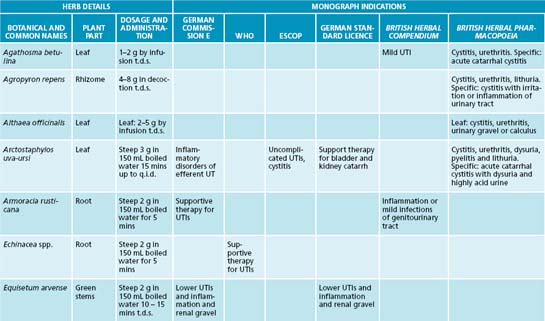

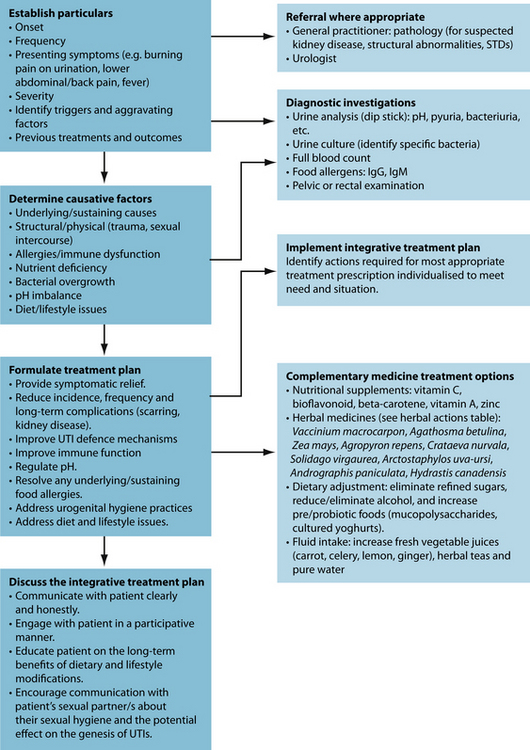

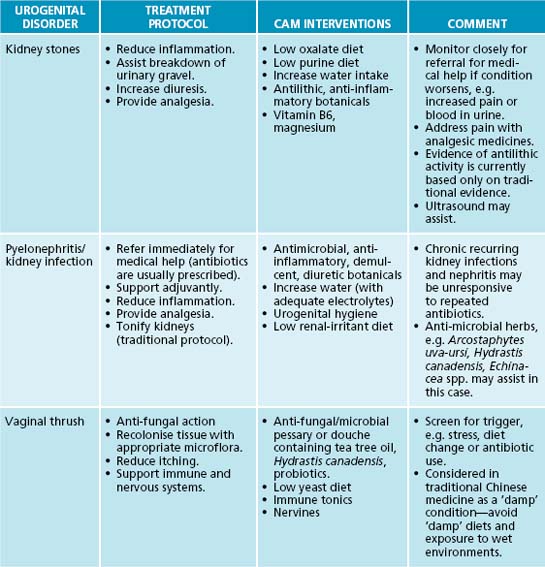

The primary naturopathic treatment goals for UTIs are to initially combat the urinary pathogen and ameliorate symptoms such as pain and fever. Long-term treatment protocols are to enhance the patient’s immune function to appropriately remove and resist infection, remove possible irritants, restore urinary tract microflora, prevent bacteria from adhering to the mucosal wall of the bladder, and promote preventive behaviours. Herbal medicine has a strong tradition of use in genitourinary conditions (see Table 27.1), although many herbal medicines’ mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy have yet to be validated.

Antimicrobial activity

Encouraging healthy bacterial balance may be achieved by preventing dysbiosis and promoting healthy gastrointestinal bacteria populations. As most infections are the result of E. coli from the digestive tract, promoting a diet that favours healthy microflora ratios may be beneficial in reducing the incidence of UTI. A Finnish study, for example, found that women who consumed fermented dairy products containing probiotic strains had a reduced risk of developing UTI.11 The consumption of fresh juices, particularly berry juices, was also associated with decreased risk of developing UTI. Clinical investigation of women who are predisposed to recurrent UTI has also uncovered reduced beneficial microflora populations even during times of non-infection.12,13

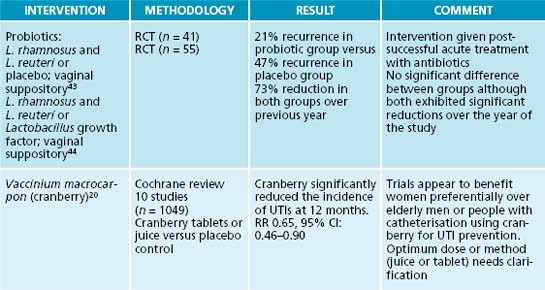

Although it is known that pathogenic urogenital flora proliferate at the time of infection, attempts to restore balance with probiotic supplements to reduce UTI show mixed results.14 Specific strains of probiotics can be beneficial for preventing recurrent UTIs in women and generally have a good safety profile. Lactobacillus rhamnosus and L. reuteri either intravaginally or orally are most effective, while L. casei shirota and L. crispatus showed efficacy in some studies; L. rhamnosus does not seem as effective.15,16 Controversy still surrounds the use of probiotics for UTI prophylaxis due to limited and mixed evidence. As with all instances in using specific probiotic strains for specific therapeutic effects, care needs to be taken to identify the appropriate strain (see Chapter 3 on irritable bowel syndrome for more discussion on suitable probiotic strains for specific conditions).

The isoquinoline alkaloid berberine from Hydrastis canadensis, Coptis chinensis and Berberis vulgaris has a strong effect in treating UTIs due to bacteriostatic activity.17 Its effects have been confirmed against a number of bacteria including Staphylococcus spp., E. coli and Streptococcus spp.18 Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, rich in the phenolic constituent arbutin, also provides strong antimicrobial activity and has preliminary clinical evidence.19 Clinical studies using these botanicals are now required to confirm this activity in humans.

Inhibition of bacteria adhering to bladder wall

A key protocol in treating UTIs is to reduce bacterial proliferation in the bladder and their adherence to the bladder wall. In addition to increasing diuresis and providing an antimicrobial and bacteriostatic action, interventions that interfere with bacterial adherence will be of benefit. A key lifestyle measure in reducing bacterial colonisation and adherence on bladder tissue is complete urination after sexual intercourse. The main phytotherapy studied for this action is Vaccinium macrocarpon (cranberry), and its cousins blueberry and bilberry. In vitro and animal studies have demonstrated that cranberry consumption inhibits the binding of bacterial strains such as E. coli to uroepithelial cells.17,19 It appears that the anthocyanidins are responsible for this activity. A Cochrane review and meta-analysis revealed that cranberry or cranberry and lingonberry significantly reduced people’s chances of developing UTIs over a 12-month period.20 It was concluded that cranberry juice or tablets may preferentially benefit women with chronic recurring UTIs compared with elderly men or people with bladder infections due to catheterisation.

A botanical with traditional use in UTIs is Juniperus spp. This medicinal plant may provide an anti-UTI effect via bacteriostatic, diuretic and anti-adhesion effects, but to date no human clinical trials substantiate this.19 It should be noted that a common misconception exists about Juniperus spp. and nephrotoxicity. Close evaluation of the literature reveals that a review of the evidence does not support this effect, and that previous case studies may be based on adulteration of the juniper oil.19 As mentioned previously, the isoquinoline alkaloid berberine has a potential effect in treating UTIs due to bacteriostatic action; this constituent also has demonstrated anti-adhesion activity against a number of bacteria including Staphylococcus spp., E. coli and Streptococcus spp.18,17 The nutrient D-mannose may also provide anti-adhesion activity against bacteria such as E. coli. This simple sugar has been shown to bind to uroepithelial cells to which bacteria normally adhere, thereby interfering with colonisation.17 While a promising intervention it should noted that current evidence is based on in vitro and animal studies.

Enhancement of diuresis

The most obvious way to increase diuresis is by use of aquaretics: agents that increase water excretion via effects on glomerular filtration as opposed to affecting electrolyte control with diuretics.19 Water and herbal teas related to treatment are the preferable methods of increasing liquid intake. Although most botanicals used for this effect are regarded as being aquaretic, there have been some studies on the diuretic effects of certain herbs that are noted to be potentially beneficial in conditions like oedema and hypertension.19 Reference is particularly made in this instance to the herb Taraxacum officinale where the leaf especially has demonstrated diuretic affects due in part to potassium content.21 An added benefit for use of T. officinale in diuresis is that potassium levels are compensated for the loss of this mineral in urine output.22 The first human study to evaluate the diuretic effects of this herb showed promise for its use as a diuretic.23 The pilot study used fresh leaf hydroethanolic extract of T. officinale (8 mL t.d.s.) in 17 participants to investigate whether an increased urinary frequency and volume would result (compared to prerecorded baseline measurements). Results revealed a significant increase in the frequency of urination in the 5-hour period after the first dose. There was also a significant increase in the excretion ratio in the 5-hour period after the second dose of extract. The third dose, however, failed to significantly alter any of the measured parameters. For more detail on the use of T. officinale as a diuretic, refer to Chapter 10 on hypertension.

Reduction of inflammation and pain

Symptomatic relief of pain and inflammation is also important in treating UTIs. The use of herbal anti-inflammatories and demulcents are specifically indicated and are highly recommended (see the detailed lists in Tables 27.1 and 27.4). Further details on treating pain and inflammation may be found in Chapter 28 on autoimmunity, Chapter 22 on osteoarthritis and Chapter 37 on pain management.

Preventive measures

Clinicians are advised to provide lifestyle advice to assist in UTI prevention (see Table 27.2). A key consideration is to advise that the patient communicate to their sexual partner/s about the potential influence their sexual hygiene may have on the genesis of a UTI. To effectively prevent UTIs, the sexual partner is advised to adopt the same lifestyle advice as the patient being treated (especially males) as they may be the prime source of recurrent infection. Although studies on fluid intake and susceptibility to UTI appear inconclusive, adequate hydration is important and may improve the results of interventional treatment.25 Supporting healthy immune function is also an important preventive measure. One small trial has found that 100 mg of vitamin C reduced the incidence of UTI in pregnant women.26 A recent meta-analysis noted, however, that vitamin C may be of little use as an acidifying agent lowering urinary pH.27 The

Table 27.2 Lifestyle factors useful in the prevention of UTIs28,29,11

| Hydration and urination |

Medicinal teas

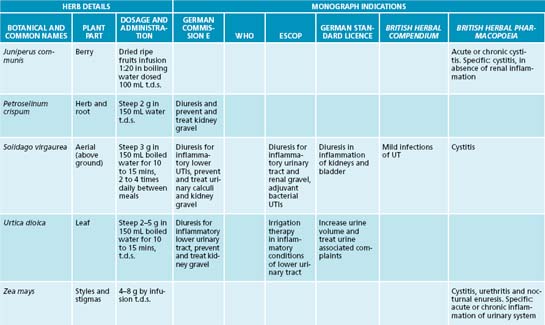

One potentially beneficial CAM intervention in the treatment of UTIs is the use of medicinal teas, which, in addition to providing antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, demulcent or diuretic activity, also increase the amount of water consumed. As Reinard Ludewig (1989)40 espoused, ‘persons who prefer their daily coffee, cocoa, or tea to caffeine tablets are unknowingly accepting and enjoying the pleasure of gentle-acting phytomedicines’. Traditional herbal pharmacopoeias advocate the use of medicinal herbal teas (infusions and decoctions) for the treatment of UTIs, to promote diuresis, disinfect the urine and prevent the formation of renal gravel and stones (see Table 27.3).40

Writings in The American Eclectic Materia Medica and Therapeutics (1863) reflected the practice of the day, declaring without doubt that ‘infusion and decoction are the most eligible forms of administering such vegetable remedies’ as they ‘yield either a part or all of their virtues to water infusion’. They reiterated that, although much ‘tea’ was laughed at, ‘this practice has proven eminently successful’ and the added advantage was ‘that the patient will receive sufficient [liquid], a matter that is of the first importance in the treatment of many diseases’.41

Teas, as aqueous preparations, are efficient in extracting water-soluble plant chemicals, in particular essential oils, and the presence of saponins enhances the bioavailability of other, less-soluble compounds.38 Furthermore, therapeutic infusions have added benefits not gleaned from herbal liquid extracts and solid dose forms. The ritual of preparing a herbal tea, savouring the aroma and slowly sipping, to ultimately experience the

soothing, warm sensation that, at some level, brings relaxation to an otherwise stressed individual, has added therapeutic value.

There are important considerations in the selection of herbs to create a balanced blend that is both therapeutic and palatable. Weiss instructs that every formulation requires three components: (1) the basic remedy (the remedium cardinal), (2) an adjuvant to enhance or complement the action of the basic remedy, and (3) a ‘corrigent’ to improve palatability and compliance.42 Preparation instructions also need to be communicated well as the method used has the potential to impede or potentiate the therapeutic benefits of an herbal tea. Herbal parts containing volatile oils (for example, in delicate leaves and seeds) should be gently infused in hot water in an enclosed vessel (teapot) so as not to damage or lose these therapeutic plant compounds. Chemical compounds contained in harder bark or root components may need to be ‘drawn out’ in boiling water for 10 to 15 minutes. Furthermore, dosage instructions will potentiate the curative properties attributed to both the preparation and the ingestion practices of taking tea. Unless otherwise indicated, 1 or 2 teaspoons of tea are used per cup (150 mL) of hot water, of which 2 to 3 cups are to be taken daily on an empty stomach to aid absorption, preferably drunk on rising, mid-afternoon and before bed.42

INTEGRATIVE MEDICAL CONSIDERATIONS

There are important medical implications associated with UTIs. UTIs elevate the risk of pyelonephritis and are associated with impaired renal function and end-stage renal disease.1 It is therefore imperative that anyone presenting with an UTI with suspected kidney disease should be referred to a general practitioner for assessment with possible further referral to an urologist (see Table 27.4 for other common urinary conditions).30

Conventional treatment of UTIs with antibiotics along with a high recurrence rate of UTIs, especially among young women, has led to issues of antibiotic resistance. Various authors have reported on antibiotic resistance and its implications for the long-term use of antibiotics for the effective management of urinary tract and kidney infections.31,32,33,34 One case-control study concluded that exposure to antibiotics is a strong risk factor for a resistant E. coli UTI.35 An integrative approach using various herbal and nutritional therapeutics to support and resolve UTIs may provide promise. A Norwegian study found that acupuncture reduced the UTI rate by around half in women who had a history of recurrent UTIs.36 However, treatment needs to be individualised based on the diagnosis and prescription of trained practitioners. Acupuncture also seems to result in improved quality of life of women with recurrent UTIs.37

Prescription

The herbal treatment is designed to promote UTI defence mechanisms by:

Vaccinium macrocarpon, Echinacea angustifolia and Hydrastis canadensis provide antiadhesive (bacterial), immune-enhancing and antimicrobial activity, respectively. The use of the botanical as a medicinal tea (detailed below) will not only increase urine volume and diuresis, but it will also provide soothing demulcent effects and further enhance the anti-inflammatory and antiseptic actions of the herbal prescription. The herbal tea is advised to be taken at a different time to the Hydrastis canadensis tablets as the tannins from peppermint and bearberry may bind with the berberine alkaloids. Although peppermint is spasmolytic and antimicrobial in action,9 the main purpose for it being included in the tea blend is to enhance flavour (taste).

Herbal prescription

| Vaccinium macrocarpon tablets 3 g |

| Dose: 2 tablets t.d.s. |

| Echinacea angustifolia (standardised for alkylamides) tablets 1 g |

| Dose: 2 tablets t.d.s. |

| Hydrastis canadensis (standardised for berberine) tablets 1 g |

| Dose: 1 tablet t.d.s. |

| Herbal tea: buchu, corn silk, goldenrod, bearberry, marshmallow, peppermint |

| 1 cup t.d.s. on empty stomach on rising, mid-afternoon and before bed (prepare in teapot fresh each morning for use throughout the day). See the herb tea blend preparation box below for further instructions. |

Dietary and lifestyle advice

Recommendations are made (as in Table 27.2) to further reduce susceptibility to and incidence of UTIs and to promote general wellbeing and healthy immune function. Dietary advice may include reducing or eliminating intake of refined sugar and alcohol, and increase pre- and probiotic foods (mucopolysaccharides and cultured yoghurts).

HERBAL TEA BLEND

| Herb/herb part | g per week |

|---|---|

| Buchu leaves | 20 |

| Corn silk styles and stigmas | 20 |

| Goldenrod aerial parts | 10 |

| Bearberry leaves | 15 |

| Marshmallow root | 15 |

| Peppermint leaves | 20 |

| Total | 100 g |

Increased fluid intake, using fresh vegetable juices (for example, a blend of celery, carrot, lemon and ginger), herbal teas and pure water, is also advised. Urogenital hygiene practices—pre- and postcoital hygiene and increased urination—are also recommended.

Expected outcomes and follow-up protocols

KEY POINTS

Barrons R., Tassone D. Use of Lactobacillus probiotics for bacterial genitourinary infections in women: a review. Clin Ther. 2008;30:453-468.

Head K. Natural approaches to prevention and treatment of infections of the lower urinary tract. Altern Med Rev. 2008;13:227-244.

Jepson R., Craig J. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (23):2008. CD001321

Yarnell E.. Botanical medicines for the urinary tract. World J Urol. 2002;20:285-293.

1. Wein A.J., et al. Campbell-Walsh Urology, 9th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

2. Boon, et al. Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine, 20th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

3. Kumar P., Clark M. Clinical medicine, 5th edn. London: W.B. Saunders; 2002.

4. Foxman B., et al. Urinary tract infection: self reported incidence and associated costs. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:509-515.

5. Murtagh J. General practice. Sydney: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

6. Scholes D., et al. Risk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection in young women. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1177-1182.

7. Boyko E., et al. Diabetes and the risk of acute urinary tract infection among postmenopausal women. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1778-1783.

8. Stamm W. Estrogens and urinary-tract infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:623-624.

9. Blumenthal M., et al. Herbal medicine expanded Commission E monographs. Newton: Integrative Medicine Communications; 2000.

10. British Herbal Medicine Association Scientific Committee. British herbal pharmacopoeia. Bournemouth: British Herbal Medicine Association; 1983.

11 Kontiokari T., et al. Dietary factors protecting women from urinary tract infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:600-604.

12. Gupta K., et al. Inverse association of H2O2-producing lactobacilli and vaginal Escherichia coli colonization in women with recurrent urinary tract infections. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:446-450.

13. Kirjavainen P., et al. Abnormal immunological profile and vaginal microbiota in women prone to urinary tract infections. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:29-36.

14. Reid G. Probiotic agents to protect the urogenital tract against infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:437S-443S.

15. Barrons R., Tassone D. Use of Lactobacillus probiotics for bacterial genitourinary infections in women: a review. Clin Ther. 2008;30:453-468.

16. Reid G. Probiotic lactobacilli for urogenital health in women. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:S234-S236.

17. Head K. Natural approaches to prevention and treatment of infections of the lower urinary tract. Altern Med Rev. 2008;13:227-244.

18. Scazzocchio F., et al. Antibacterial activity of Hydrastis canadensis extract and its major isolated alkaloids. Planta Med. 2001;67:561-564.

19. Yarnell E. Botanical medicines for the urinary tract. World J Urol. 2002;20:285-293.

20. Jepson R.G., et al. Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2004. CD001321

21 Hook I., et al. Evaluation of dandelion for diuretic activity and variation of potassium content. Int J Pharmacog. 1993;31(1):29-34.

22. Schütz K., et al. Taraxacum—a review on its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:313-323.

23. Clare B.A., et al. The diuretic effect in human subjects of an extract of Taraxacum officinale folium over a single day. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(8):929-934.

24. Wyman J.F., et al. Practical aspects of lifestyle modifications and behavioural interventions in the treatment of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(8):1177-1191.

25. Beetz R. Mild dehydration: a risk factor of urinary tract infection. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:S52-S58.

26. Ochoa-Brust G., et al. Daily intake of 100 mg ascorbic acid as urinary tract infection prophylactic agent during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:783-787.

27. Masson P., et al. Meta-analyses in prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23:355-385.

28. Foxman B., Frerichs R. Epidemiology of urinary tract infection: II. Diet, clothing, and urination habits. Am J Public Health. 1985;75(11):1314-1317.

29. Foxman B., Chi J. Health behavior and urinary tract infection in college-aged women. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(4):329-337.

30. Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Dis Mon. 2003;49:53-70.

31 Foxman B., et al. Antibiotic resistance and pyelonephritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:281-283.

32. Karlowsky J.A., et al. Fluoroquinolone-resistant urinary isolate of Escherichia coli from outpatients are frequently multidrug resistant: results from the North American Urinary Tract Infection Collaborative Alliance-Quinolone Resistance Study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(6):2251-2254.

33. McNulty C.A.M., et al. Clinical relevance of laboratory-reported antibiotic resistance in acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:1000-1008.

34. Mazzulli T. Resistance trends in urinary tract pathogens and impact on management. J Urol. 2002;168:1720-1722.

35. Hillier S., et al. Prior antibiotics and risk of antibiotic-resistant community-acquired urinary tract infection: a case-control study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:92-99.

36. Alraek T., et al. Acupuncture treatment in the prevention of uncomplicated recurrent lower urinary tract infections in adult women. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1609-1611.

37. Alraek T., Baerheim A. An empty and happy feeling in the bladder … : health changes experienced by women after acupuncture for recurrent cystitis. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:219-223.

38. Mills S., Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

39. Grases F., et al. Urolithiasis and phytotherapy. Int Urol Nephrol. 1994;26:507-511.

40. Cited in Schulz V., et al. Rational phytotherapy a physicians’ guide to herbal medicine. Berlin: Springer; 2001.

41 Bergner P. Tinctures vs teas. Medical Herbalism. 2001;10(4):3.

42. Weiss R. Herbal medicine. Gothenburg: Ab Arcanum and Beaconsfield: Beaconsfield Publishers; 1985.

43. Reid G., et al. Influence of three day antimicrobial therapy and Lactobacillus vaginal suppositories on recurrence of urinary tract infections. Clin Ther. 1992;14:11-16.

44. Reid G., et al. Installation of Lactobacillus and stimulation of indigenous organisms to prevent recurrence of urinary tract infections. Microecol Ther. 1995;23:32-45.