Problem 30 Recurrent collapse in a 56-year-old truck driver

A 56-year-old truck driver presents to the emergency department with a 6-month history of recurrent episodes of loss of consciousness. He has had four episodes in total and his most recent event occurred while he was driving his vehicle. Luckily he was not seriously injured. You are the attending doctor in the emergency department and are assessing him.

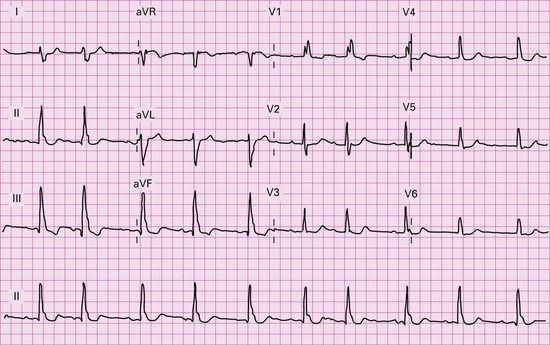

Physical examination is essentially unremarkable with no abnormal cardiovascular findings and a normal neurological exam. The only positive finding is that of centripetal obesity consistent with the patient’s elevated body mass index. You request an ECG in light of the normal physical examination (Figure 30.1).

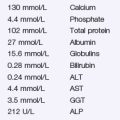

The patient went on to have a 24-hour ambulatory cardiac monitor. He had several episodes of syncope during this time. Figure 30.2 shows the electrocardiogram during the events.

Answers

Revision Points