52 Rectus Sheath Block

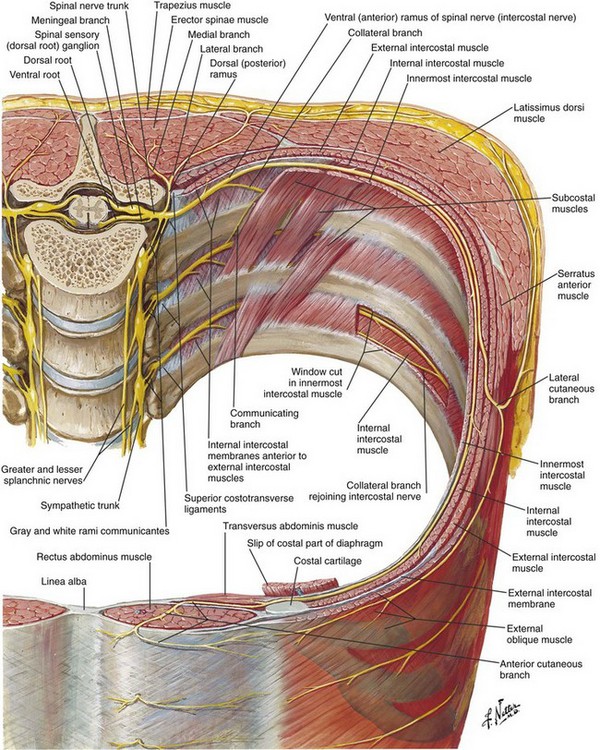

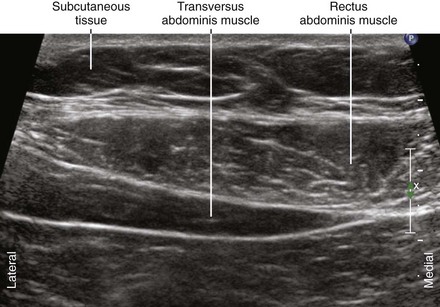

The rectus abdominis is a vertical muscle of the anterior abdominal wall. The muscle is divided into compartments by the midline linea alba, paramedian linea semilunaris, and transverse fibrous bands.1 Muscles of the lateral abdominal wall (the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis) become aponeurotic as they approach the midline. The rectus sheath consists of the rectus abdominis muscles surrounded by these aponeuroses.

Above the arcuate line, the transversalis fascia and the aponeuroses separate the rectus abdominis muscle from the abdominal cavity. Caudal to the arcuate line, the rectus abdominis muscle is in direct contact with the transversalis fascia. In this location, all three of the lateral abdominal wall muscles (external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus) have their aponeuroses pass anterior to the rectus abdominis muscle.2

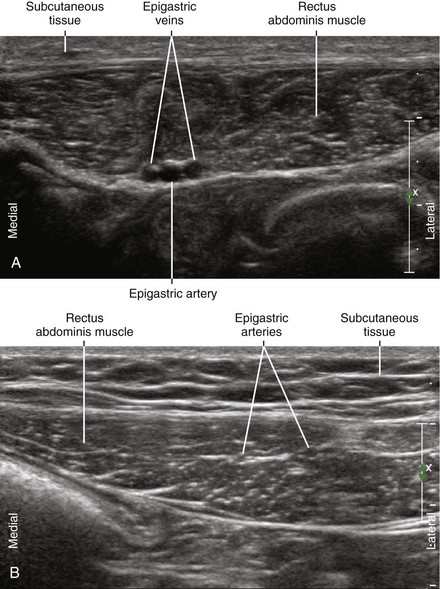

Anterior cutaneous branches of the intercostal nerves enter the rectus sheath from the posterior and lateral sides.3 Epigastric arteries and veins are sometimes identified within the rectus sheath. The anterior intercostal nerves can run alongside these vessels before rising to the surface through the rectus abdominis muscle. The nerves of the rectus sheath are too small to be directly imaged with ultrasound.

Rectus sheath block is useful as part of a combined anesthetic technique for outpatients.4,5 The usual indication for this block is to provide pain relief after repair of umbilical or incisional hernias. It provides an excellent alternative to straight general anesthesia or epidural blocks for surgical procedures around the midline of the abdominal wall.

Suggested Technique

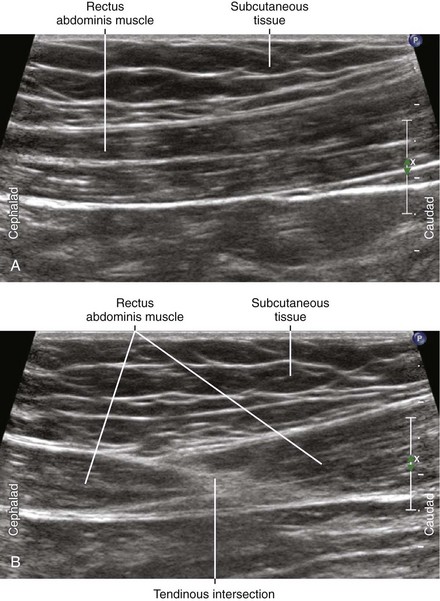

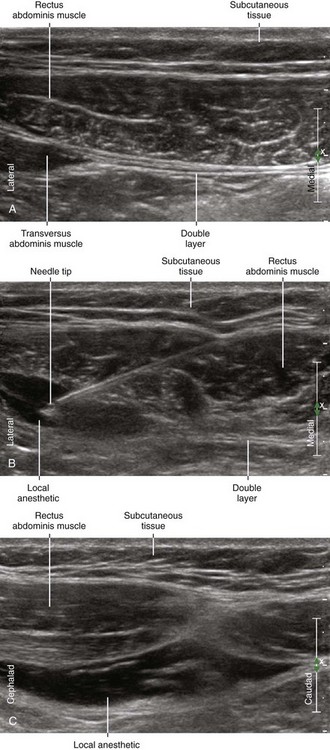

Because of the compartmental nature of the rectus abdominis muscle, two or four injections are usually performed for periumbilical surgery (right and left sides, and sometimes above and below the umbilicus). About 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic is injected per side per compartment in adult patients. Because the tendinous inscriptions of the muscles are not complete posteriorly,6 some communication between compartments is possible. If local anesthetic is observed to distribute between compartments, no further injection is necessary.

In one study, 21% of rectus sheath injections guided by traditional loss-of-resistance techniques were intraperitoneal.7 These intraperitoneal injections were detected by ultrasound imaging after initial needle placement. Although no complications were observed in this study, intraperitoneal injections are not clinically effective and presumably place patients at risk for injury.

Key Points

| Rectus Sheath Block | The Essentials |

|---|---|

| Anatomy | The nerves of the rectus sheath enter the posterolateral side of the RA. |

| The TA lies under the lateral aspect of the RA in the supraumbilical region. | |

| Epigastric arteries and veins usually lie deep within the midportion of the RA. | |

| Tendinous intersections divide adjacent rectus sheath compartments. | |

| These tendons are thought to be incomplete posteriorly. | |

| This should allow communication between adjacent compartments. | |

| Positioning | Supine |

| Operator | Standing on the side of the patient |

| Display | Across the table |

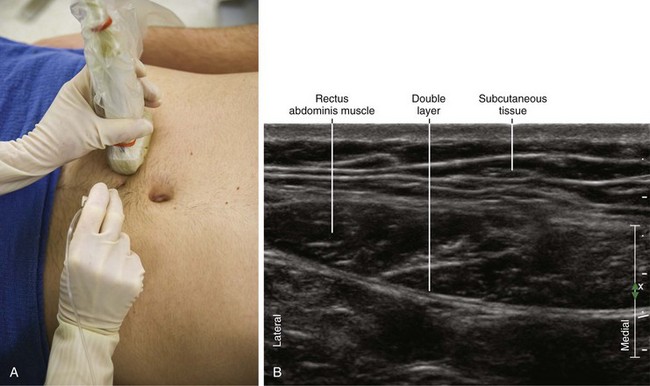

| Transducer | High-frequency linear, 38- to 50-mm footprint |

| Initial depth setting | 35 to 50 mm |

| Needle | 20 to 21 gauge, 70 to 90 mm in length |

| Anatomic location | Begin by scanning the RA in transverse view. |

| Slide transducer to midway between the tendinous intersections. | |

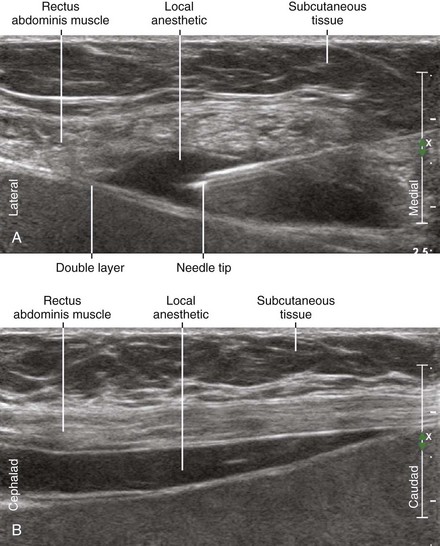

| Approach | Transverse view of RA, in-plane from lateral to medial. |

| Aim for the posterolateral corner of the RA. | |

| Place the needle tip between the RA and underlying fascial double layer. | |

| If necessary, scratch the needle tip against the fascial double layer. | |

| Bilateral injections are necessary for midline anesthesia. | |

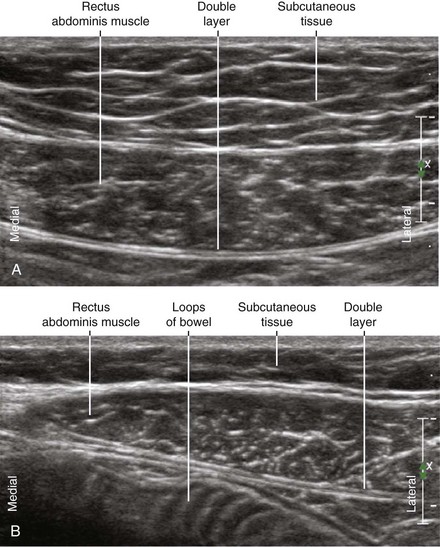

| Sonographic assessment | Desire side-to-side (medial-lateral) distribution over the double layer. |

| “Swimming pool” or “smile” shaped appearance of distribution between RA and double layer. | |

| Desire cephalocaudad distribution between adjacent compartments. | |

| The “handlebar mustache” appearance of the longitudinal distribution between compartments. | |

| Anatomic variation | Position of epigastric arteries and TA varies. |

RA, Rectus abdominis muscle; TA, transversus abdominis muscle.

Clinical Pearls

• The extent to which the abdominal wall muscles underlie the lateral corner of the rectus abdominis muscle is variable. In some cases there is no underlying muscle to separate the rectus from the abdominal cavity.

• The needle tip should be scratched against the double layer but not actually puncture it so as to place the tip between the rectus muscle and the double layer.

• A few milliliters of local anesthetic can be injected as the needle is removed to cover the path of nerves through the rectus muscle.

• The best way to perform rectus sheath blocks is to inject forward on one side and back for the contralateral side. In this fashion the ultrasound display screen and operator remain in one position for bilateral injections.

• The fibers of the rectus abdominis course in a parallel direction, with the muscle divided by transverse tendinous intersections.

• The nerves of the rectus sheath are too small (100 µ diameter) to be directly imaged with ultrasound.3 Therefore, ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block relies on injecting between the rectus abdominis muscle and the underlying double layer of fascia at the point where the nerves are known to enter the rectus sheath.

• The rectus abdominis muscle is slightly narrower near its ends at the xiphoid process and pubic bone. The rectus sheath narrows at its cephalad and caudad ends as the linea semilunaris tapers toward the midline.

1 Ali QM. Sonographic anatomy of the rectus sheath: an indication for new terminology and implications for rectus flaps. Surg Radiol Anat. 1993;15:349–353.

2 Monkhouse WS, Khalique A. Variations in the composition of the human rectus sheath: a study of the anterior abdominal wall. J Anat. 1986;145:61–66.

3 Rozen WM, Tran TM, Ashton MW, et al. Refining the course of the thoracolumbar nerves: a new understanding of the innervation of the anterior abdominal wall. Clin Anat. 2008;21:325–333.

4 Willschke H, Bösenberg A, Marhofer P, et al. Ultrasonography-guided rectus sheath block in paediatric anaesthesia: a new approach to an old technique. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:244–249.

5 Sandeman DJ, Dilley AV. Ultrasound-guided rectus sheath block and catheter placement. Aust N Z J Surg. 2008;78:621–623.

6 Connell D, Ali K, Javid M, et al. Sonography and MRI of rectus abdominis muscle strain in elite tennis players. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1457–1461.

7 Dolan J, Lucie P, Geary T, et al. The rectus sheath block: accuracy of local anesthetic placement by trainee anesthesiologists using loss of resistance or ultrasound guidance. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:247–250.