22 Rectal/perianal mass and colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cause of cancer mortality in most developed countries. Screening and early endoscopic intervention form the crux of management strategy.

Rectal or Perianal Mass

There are three ways a patient with a perianal or rectal mass may present:

The causes of a lump in the rectum are listed in Box 22.1.

History

Establish when the lump was first recognised and whether it has changed over time. An intermittent nature suggests that the lump relates to prolapse of a lesion from the rectum (e.g. haemorrhoids or rectal prolapse). Determine if the lump could be manually reduced when the lump is external to the anus. Haemorrhoids are a classic example of a potentially reducible lump, but the differential diagnosis includes rectal prolapse and hypertrophied anal papilla. An acute time course favours conditions such as thrombosed internal or external haemorrhoids. Tenderness suggests an infective process such as an ischiorectal abscess (Chapter 12).

Another key symptom is rectal bleeding. Never ignore rectal bleeding and never assume it has a benign cause; bleeding should raise the suspicion of colorectal cancer. Ask about a family history of gastrointestinal disease and, in particular, colon cancer or polyps. Less commonly, a solitary rectal ulcer secondary to prolapse of the rectum can cause bleeding and tenesmus. The passage of mucus may occur with benign or malignant tumours as well as ulceration. Systemic symptoms such as weight loss (e.g. with malignancy) or fever (e.g. with an abscess) may also help point towards the correct diagnosis. A history of menstrual bleeding associated with a tender lump may suggest a perineal endometrial deposit that rarely occurs.

Physical examination

Inspection

Careful inspection is crucial (see Chapter 12) but, importantly, one must expect to find an abnormality. Place the patient in the left lateral position with the buttocks well over the edge of the couch. Part the buttocks, looking for perianal skin tags, which may be associated with pruritus due to suboptimal hygiene. These are usually haemorrhoidal remnants, but they can occasionally be an indicator of a systemic process such as Crohn’s disease (Chapter 15). A perianal haematoma may be visible, which is usually small (under 1 cm). Rectal prolapse can occur at any age; suspect this if the anus is patulous or gaping. Ask the patient to strain; perineal descent may be seen and sometimes rectal prolapse (circumferential folds of red mucosa) may be demonstrated.

Sigmoidoscopy and proctoscopy

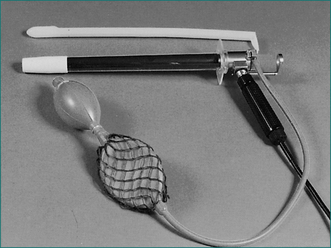

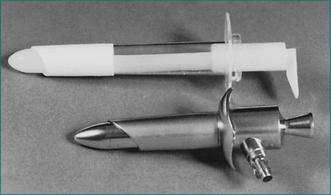

The examination is most commonly performed with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position. In some centres, particularly those equipped with specialised tables, the examination is performed with the patient in the jack-knife position resting on the knees. Usually, adequate clinical information can be achieved without rectal preparation. When the rectum is totally loaded, it can be cleared by inserting an enema; full mechanical bowel preparation is not needed for this examination. Most patients will be anxious about proctoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. They need not see the instrument (Figs 22.1 and 22.2). The examiner needs to reassure the patient, pointing out that the diameter of the instrument is less than the diameter of a large stool and that the examination will be discontinued if there is excessive discomfort.

Tumours of the Colon and Rectum

History

The classic right-sided colon cancer is soft, protuberant and located where the lumen is large and the contents semisolid; anaemia is therefore more likely than obstruction. The classic left-sided colon cancer is annular, stenosing and located where the lumen is narrow and contents are firm; consequently, obstruction is more likely (Fig 22.3). Cancers may form a fistula into the bladder or elsewhere. Advanced cancers may be asymptomatic, while a very early caecal cancer may occasionally present with appendicitis, having obstructed the appendiceal opening.

Rarely, infective endocarditis caused by Streptococcus bovis or Clostridium septicus is the first manifestation of colon cancer.

Physical examination

The rectum may be evaluated with a rigid ‘sigmoidoscope’—a misnomer in that the sigmoid is not adequately seen with this 30-cm instrument. Full evaluation of the colon is necessary with a colonoscopy to identify any tumours (Fig 22.3) and to rule out synchronous cancers. The bowel must be prepared (emptied of all stool) to see the wall clearly. Colonoscopy has the advantage of allowing biopsies and/or therapeutic intervention, and the disadvantage that it can cause rare bowel perforation.

Investigation

Diagnosis is made on the basis of history, physical examination and special investigation (Table 22.1).

Table 22.1 Preoperative assessment of patients with colorectal carcinoma

| Investigation | Comment |

|---|---|

| Blood count, electrolytes, creatinine and liver function tests | Results probably will be normal; useful base-line assessment if major surgery planned |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) |

Note: Intravenous pyelogram, abdominal ultrasound and MRI may be indicated in special circumstances.

Preoperative investigations should include a full blood count, electrolyte tests and liver function tests. Baseline carcinoembryonic antigen can be sought to aid follow-up, although the benefit of this is controversial (Ch 17). A chest x‑ray examination may detect metastatic disease. If advanced disease is suspected, computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen may be useful; surgery may still be needed for palliation.

Colorectal cancer

Aetiology

Inflammatory bowel disease (particularly longstanding ulcerative colitis of more than 8 years) leads to an increased incidence of colon cancer (Ch 14).

Familial adenomatous polyposis: classic and attenuated

FAP is caused by an inherited autosomal-dominant gene located on chromosome 5q. Polyps usually appear in the second decade of life. Patients usually have no symptoms until colon cancer develops. More than 95% of patients will have polyps on sigmoidoscopy by the age of 30 years, so the condition can usually be diagnosed by sigmoidoscopy in adults. The number of polyps in a colectomy specimen of a patient with FAP averages approximately 1000. Colorectal cancer inevitably occurs in patients with FAP by the age of 50 years, approximately 10–15 years after the first onset of polyps. Where a mutation in APC is identified in the proband, predictive testing can be done on other family members to identify individuals at risk. Those found negative for the family-specific APC mutation do not require screening beyond that offered to individuals with average risk.

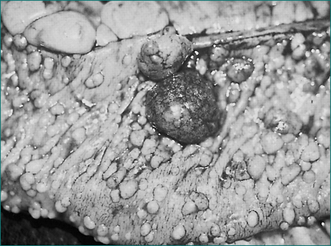

The presence on sigmoidoscopy of more than 100 polyps that are adenomas histologically establishes the diagnosis (Fig 22.4). Such patients should be referred to a centre of expertise because it can be difficult to detect cancer early in these cases.

Surgical management is the only acceptable approach unless there are other contraindications.

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

Polyps and the polyp-cancer sequence

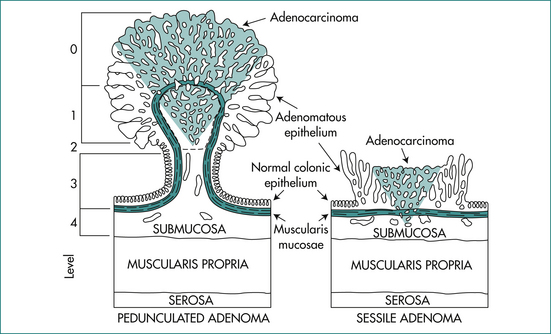

The neoplastic lesion is ‘superficial’ if it is an adenomatous polyp with absence of invasion in the lamina propria, or if it is an early carcinoma with invasion of the lamina propria but the depth of penetration was limited to the submucosa in the colon. Superficiality relates to the potential for complete cure after endoscopic mucosal resection.

Laterally spreading tumours refer to flat lesions over 10 mm in diameter.

Malignant risk in a polyp depend-on the size, microscopic architecture and site of the polyp (Table 22.2). The risks are greater with increase in size, villous architecture, and rectal site.

Table 22.2 Risk of invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas

| Parameter | Proportion of polyps with carcinoma (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Size (mm) | ≤ 5 | 0 |

| 6–15 | 2 | |

| 16–25 | 20 | |

| 26–36 | 40 | |

| ≥ 37 | > 60 | |

| Architecture | Tubular | 4 |

| Tubulovillous/villous | 30 | |

| Site | Right colon | 6 |

| Left colon | 8 | |

| Rectum | 23 |

Modified from Nusko G, Mansmann U, Altendorf HA, et al. Risk of invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas assessed by size and site. Int J Colorectal Dis 1997; 12:267–271

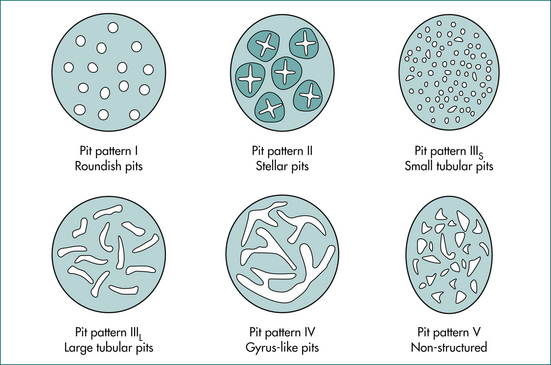

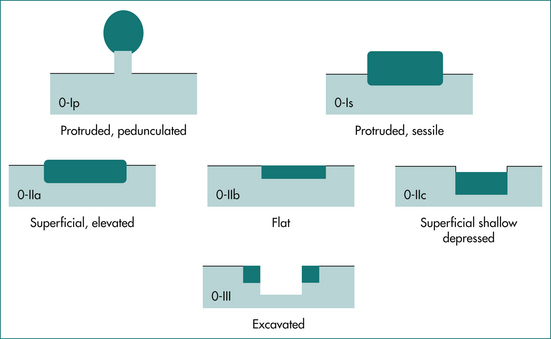

The malignant risk of a polyp may be identified by its endoscopic appearance. Advances in endoscopic technology with zoom, narrow band imaging and high-definition white-light imaging have allowed further morphological assessment of the polyp using the Kudo pit pattern (Fig 22.6) and the Paris classification (Fig 22.7) in defining those polyps likely to have submucosal invasion. Together with differentiation into granular (polyps with nodules on the surface) and non-granular (polyps with a smooth surface) subtypes, the endoscopist is able to determine whether or not a polyp would be suitable for endoscopic mucosal resection (Table 22.3).

Figure 22.6 Kudo pit pattern.

From Kudo S, Hirota S, Nakajima T, et al. Colorectal tumours and pit pattern. J Clin Pathol 1994; 47:880–885.

Figure 22.7 Paris grading.

From Paris Workshop Participants. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 58(suppl 6):S3–S43, with permission.

Table 22.3 Risk of malignancy in polyps

| Classification | SMI (%) | M (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Granular | 7 | |

| Non-granular | 14 | |

| Paris grade | ||

| 0–Is | 7 | |

| 0–IIa | 3 | |

| 0–IIc or IIa+c | 46 | |

| Pit pattern | ||

| I–II | 0 | 0 |

| IIIL | 0 | 4 |

| IIIS | 4 | 9 |

| IV | 4 | 18 |

| V | 34 | 35 |

SMI = submucosal invasion; M = intramucosal cancer.

Adapted from Uraoka T, Saito Y, Matsuda T, et al. Endoscopic indications for endoscopic mucosal resection of laterally spreading tumours in the colorectum. Gut 2006; 55(11):1592-1597; Kudo et al. Pit pattern in colorectal neoplasia: endoscopy magnifying view. Endoscopy 2001; 33(4):367-373.

There is no consensus on these criteria, but these patients are quite distinct because of the frequency, distribution and often large size of the hyperplastic polyps. These polyps may arise in patients with a family history of colorectal cancer, are often large and are found in the right colon. Due to the risk of developing right-sided colorectal cancer, these patients should have a follow-up colonoscopy at a relatively short interval (1–2 years) and have the polyps removed endoscopically.

Staging of colorectal cancer

Historically, the Dukes’ classification is best known and still widely used for colorectal cancer:

However, this classification is based solely on the pathologist’s examination of the resected surgical specimen. The presence of residual tumour at the completion of operation after resection of the primary is a powerful prognostic factor that influences long-term survival, but it is not recognised in the traditional Dukes’ classification. Another approach to staging is the TNM classification (Table 22.4).

| Stage grouping | |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Tis N0 M |

| Stage 1 | Tis 1–2 N0 M0 |

Based on Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6th edn. New York: Springer Verlag; 2002, with permission.

Treatment

Polyps are usually excised endoscopically and examined histologically. If cancer is found in the polyp, further surgical resection of that segment of bowel may be indicated. However, a resection may not be necessary if there are:

The Haggitt’s level of invasion (Fig 22.8, Table 22.5) is a useful guide in considering further management for a malignant polyp after endoscopic resection, as it has been validated to determine prognosis in surgical series. Stages 0, 1, 2 and 3 do not require surgery. On the other hand, surgery would be recommended for stage 4. By definition, submucosal invasion in a sessile polyp would require surgery. However, it has been suggested that superficial submucosal invasion (under 300 mm) in such sessile polyps might also be considered low in risk.

| Haggitt level | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Intramucosal high grade dysplasia |

| 1 | Carcinoma invading the head of the polyp above the junction of the adenoma and the stalk |

| 2 | Carcinoma invading the neck of the polyp at the junction between the adenoma and the stalk |

| 3 | Carcinoma invading any other part of the polyp |

| 4 | Invasion into the submucosa of the bowel wall below the stalk in the pedunculated polyp and in the submucosa of the sessile polyp |

Obviously, comorbidity of the patient should be taken into account in the management algorithm.

Surgical treatment aims to remove the tumour with a margin of normal bowel in continuity with draining lymph nodes and blood vessels. Restoration of intestinal continuity is usually possible. In the case of low rectal cancer requiring an abdominoperineal resection, an end colostomy would result. Patients who had laparoscopically assisted colectomy have a similar survival rate to those who had open colectomy at 4 years follow-up. Laparoscopically assisted colectomy also produced better clinical outcomes, such as early recovery, less pain and reduced length of stay. It is believed that there will be reduced incidence of small bowel obstruction and incisional hernia in the long term.

Colorectal cancer screening

Guidelines frequently change and depend on the risk category, as follows:

younger than the age of first diagnosis of colorectal cancer in the family, whichever comes first (the ‘10-year rule’). Sigmoidoscopy plus double-contrast barium enema 5-yearly is an acceptable alternative to colonoscopy if the latter is unavailable, but colonoscopy is considered the ‘gold standard’. CT colonography 5-yearly is an alternative.

Anal Canal Cancer

Anal canal cancer is more commonly seen in women, although carcinoma of the anal margin is more common in men (Fig 22.9). Together, these are rare tumours constituting only 3–4% of anorectal malignancies. There is a strong association between anal canal cancer and sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV infection and condyloma acuminata caused by the human papilloma virus.

Anal canal cancer arises at or above the dentate line from transitional zone epithelium, the remnant of the cloacal membrane of early embryonic growth. However, this zone is not fixed in its relationship to other common landmarks. It may extend in the adult for a variable distance over the anal columns into the lower rectum, and it is composed of a variety of epithelia, including stratified squamous non-keratinised, stratified columnar or cuboidal and simple columnar epithelium. This partly explains the confusion that exists in the histological classification of this tumour.

Key Points

Fuchs C.S., Giovannucci E.L., Colditz G.A., et al. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1669-1674.

Gastroenterological Society of Australia [GESA]. Early detection, screening and surveillance for bowel cancer: an update for clinicians, 3rd edn. Sydney: Digestive Health Foundation; 2006.

Goldberg R.M., Meropol N.J., Tabernero J. Accomplishments in 2008 in the treatment of advanced metastatic colorectal cancer. Gastroint Cancer Re. 2009;3(suppl 2):S23-S27.

Hyman N.H., Anderson P., Blasyk H. Hyperplastic polyposis and the risk of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:2101-2104.

Jass J.R., Burt R., Hamilton S.R., Aaltonen L.A. Hyperplastic polyposis. WHO international classification of tumors. 3rd edn. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989. 135–136

Jasperson K.W., Tuohy T.M., Neklason D.W., et al. Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2044-2058.

Kapiteijn E., Marijnen C.A.M., Nagtegaal I.D., et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638-646.

Kudo S., Hirota S., Nakajima T., et al. Colorectal tumours and pit pattern. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:880-885.

Lynch H.T., de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:919-932.

Mandel J.S., Bond J.H., Church T.R., et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365-1371.

Mitchell P.J., Haboubi N.Y. The malignant adenoma: when to operate and when to watch. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1563-1569.

Moser L., Ritz J., Hinkelbein W., et al. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemoradiation or radiotherapy in rectal cancer—a review focusing on open questions. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:227-236.

Nelson H., Sargent D.J., Wieand H.S., et al. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050-2059.

Paris Workshop Participants. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(Suppl):S3-S43.

Schippinger W., Samonigg H., Schaberi-Moser R., et al. A prospective randomised phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with stage II colon cancer. Brit J Can. 2009;97:1021-1027.

Tanaka T. Colorectal carcinogenesis: review of human and experimental animal studies. J Carcinogenesis. 2009;8:1-19.