Problem 19 Rectal bleeding in a 45-year-old woman

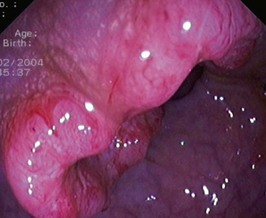

You explain to the patient that while the bleeding is most likely to be due to her haemorrhoids, a complete investigation of the large bowel is indicated. You arrange a colonoscopy. A lesion is found (Figure 19.1).

The patient wants to know if any of her children are at risk for developing this cancer.

You explain to the patient that the risk to her children is slightly greater than it would be for the general population. Table 19.1 shows the risks.

Table 19.1 Risk factors in colorectal cancer

| Family History | Risk |

|---|---|

| Up to 2 fold | |

| 3 to 6 fold | |

| 1 in 2 lifetime |

The son has heard that ‘polyps in the bowel usually turn to cancer’.

The patient remains in good health and is kept under regular surveillance.

Answers

A.4 As part of the work-up, the following investigations are required:

A.7 The aim of any cancer follow-up programme is threefold and is to detect:

Surveillance Strategies

In this instance no particular risk factors can be identified but the young age and right-sided tumour raise the issue of HNPCC. MSI (microsatellite instability) and immunohistochemistry testing and if positive subsequent assessment of the tumour for germline mutations in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes may reveal a strong possibility of HNPCC. These assessments are generally only done when patients meet one of the Amsterdam criteria/Bethesda guidelines. Approximately 10–15% of sporadic colorectal cancers will be MSI positive. The patient should be counselled that her children would be at increased risk over the general population. Use of the chart indicated in the text (Table 19.1) can be helpful.

A.9 On the assumption that the son has no digestive tract symptoms (particularly rectal bleeding), then nothing needs to be done until he is 35 (i.e. 10 years earlier than his mother’s diagnosis). The following guidelines should be applied. These recommendations for screening of first-degree relatives of patients with colorectal cancer follow the NH and MRC guidelines (Table 19.2).

| Screening Guidelines | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Category 1 |

Revision Points

Issues to Consider

, National Health and Medical Research Council, Canberra (2005) Guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer (CRC).

, www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/colon-and-rectal. Information about colon and rectal cancer treatment, prevention, genetics, causes, screening, statistics

, www.gastrolab.net. Endoscopic images presented in an MCQ fashion

, www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/colorectalcancer.html. Patient-oriented tutorial available via interactive link