Chapter 20 RECTAL BLEEDING AND HAEMORRHOIDS

RECTAL BLEEDING

Causes

Bleeding per rectum can originate from the stomach, duodenum, small intestine, colon or anorectum (Table 20.1). The diagnosis of colorectal neoplasia should be entertained in most cases: 1 in 20 patients over the age of 45 years of age who present with new onset rectal bleeding have colon cancer. The colour of the blood may indicate the source of the bleeding but the rate of bleeding needs to be taken into account. Haematochezia is the passage of bright red blood per rectum and usually indicates bleeding from the distal colon, rectum or anal canal. Dark red blood mixed in with bowel motions usually originates from the small intestine or proximal colon. Melaena, the passage of black tarry stools with characteristic odour, occurs with bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

| Region | Causes |

|---|---|

| Anorectum |

Other symptoms are useful to help localise the site of bleeding. Epigastric pain, heartburn and haematemesis or melaena are symptoms associated with bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract. Significant weight loss is associated with malignancy and inflammatory bowel disease. Change in bowel habit, tenesmus (feeling of incomplete evacuation) and blood mixed in with faeces are consistent with colonic pathology. Bloody diarrhoea indicates the possibility of colitis. Bright red rectal bleeding not mixed with faeces, blood on the toilet paper and anal pain or discharge are symptoms more indicative of an anorectal source. Personal and family history of colonic polyps, cancer and inflammatory bowel disease are important to elicit.

Management

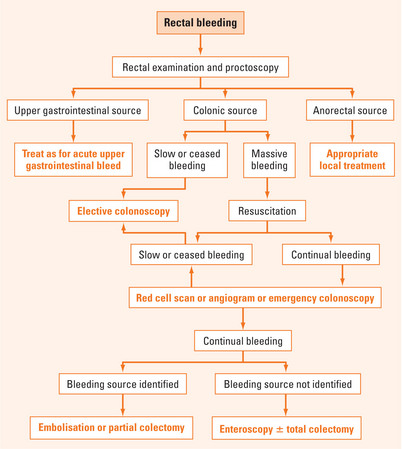

Management of rectal bleeding is shown in Figure 20.1. Initial management involves assessment and resuscitation. Any clotting abnormalities and other medical conditions should be corrected and optimised. Any evidence that the bleeding may be coming from the upper gastrointestinal tract should be looked for.

Bleeding stops spontaneously in most cases. Intervention is required for continual bleeding. Colonoscopy (after rapid cleansing in 12 hours), radiolabelled red cell scan, selective mesenteric angiography and computed tomographic angiography can be used to identify the site of bleeding. Red cell scan and angiography can localise the site of bleeding if it is faster than 0.5–1 mL/minute. Colonoscopic intervention or angiographic embolisation can be used to stop bleeding if an active site is identified. A Meckel’s scan (99Tc pertechnetate) can be useful in younger patients to exclude a bleeding Meckel’s diverticulum from ectopic gastric mucosa.

In cases where preoperative localising information is available via a red cell scan or angiographic embolisation is unsuccessful, partial colectomy can be performed. However if the patient remains haemodynamically unstable despite resuscitation and if preoperative localising studies have not been performed, total colectomy may be required as a last resort. On-table gastroscopy and colonoscopy should be considered if the site of bleeding is in doubt. Intraoperative enteroscopy may be required if there are any concerns that the site of bleeding is from the small intestine.

HAEMORRHOIDS

The dentate line separates internal haemorrhoids from external haemorrhoids. Thrombosis of external haemorrhoids (otherwise called perianal haematomas) most commonly occurs from repeated trauma to the anal verge associated with a diarrhoeal illness. If a patient presents early, the best treatment is evacuation of the clot after infiltration with local anaesthesia. If the presentation is delayed for more than five days, then conservative management with analgesia is sufficient because most of the pain would have abated by then. Patients may be left with a residual anal skin tag.

Treatment

Drug treatment of haemorrhoids

The prime objective of drug treatment is to control acute symptoms such as bleeding so that definitive treatment can be scheduled at a more convenient time. There are a number of drugs that are used in the treatment of symptomatic haemorrhoids (Table 20.2).

| Type | Action |

| Flavonoids | Improve venous tone and lymphatic drainage, reduce capillary hyperpermeability |

| Ginkgo | Increase venous tone and vessel wall resistance, decrease permeability, encourage venous blood return |

| Heparin sulfate | Normalisation of hyperaemia and mucoid secretions |

| Calcium dobesilate | Opposes breakdown of collagen, reduces blood hyperviscosity improving flow |

| Local application (nitrates, local anaesthetic preparations) | Nitrates reduce anal spasm via nitric oxide action. Local anaesthetic/corticosteroid/antibacterial combinations reduce pain and bleeding |

| Herbal and other extracts | Standardised blood leech extract reduces inflammation. Horse chestnut seed extract (aescin) fosters normal venous tone, improves venous flow, and is antiinflammatory. Other traditional remedies have astringent antiseptic, antiinflammatory and laxative properties |

Interventional treatment

Injection sclerotherapy and rubber band ligation are the two most common interventional treatment options for first- and second-degree haemorrhoids (Table 20.3). Injection sclerotherapy with phenol in almond oil causes fibrosis of the haemorrhoid at the submucosal level. Rubber band ligation involves ligation of haemorrhoidal tissue above the dentate line resulting in ischaemia of the banded tissue, with subsequent sloughing of the tissue in 7–10 days. A major secondary bleed can occur at this time if a large vessel is at the base of this banded tissue. The best treatment is to tamponade the bleeding site by insertion of a 50 mL balloon on an indwelling catheter and application of mild traction. Other complications include vasovagal syncope, pain and, rarely, sepsis. Rubber band ligation has been found to be more effective than sclerotherapy in a meta-analysis. Infrared coagulation and electrocautery cause tissue destruction and submucosal fibrosis.

| Type | Action |

| Injection sclerotherapy | Fibrosis at submucosal level |

| Rubber band ligation | Strangulation of haemorrhoids above dentate line and subsequent sloughing |

| Infrared coagulation, cryotherapy, and electrocautery | Tissue destruction and fibrosis at submucosal level |

| Haemorrhoidectomy | Excision of haemorrhoids with preservation of sphincters and skin/mucosal bridges |

| Stapled haemorrhoidopexy | Excision and stapling of circumferential rectal mucosal cuff above haemorrhoids to elevate prolapse and interrupt blood supply |

| Other treatment: HAL (haemorrhoidal artery ligation) | Ligate haemorrhoidal vessels with ultrasound guidance |

SUMMARY

The site and cause of bleeding can be identified by appropriate investigations. Common causes of massive rectal bleeding include colonic diverticular disease and angiodysplasia. Ischaemic colitis should be considered if the patient presents with abdominal pain, fever and rectal bleeding.

Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt G, Heels-Ansdell D, et al. Laxatives for the treatment of hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2005. CD004649

Brandt LJ. Bloody diarrhea in an elderly patient. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:157-163.

du Toit J, Hamilton W, Barraclough K. Risk in primary care of colorectal cancer from new onset bleeding: 10 year prospective study. Brit Med J. 2006;333:69-70.

Farrell JJ, Friedman LS. Review article: the management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1281-1298.

Hewett PJ, Maddern GJ. Haemorrhoids: evidence? ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:679-680.

Misra MC, Imlitemsu. Drug treatment of haemorrhoids. Drugs. 2005;65(11):1481-1491.