Chapter 17 Reconstructive anatomy

There is a device by which students can become comfortable with the anatomy of regions. It is the discipline of reconstructive anatomy. Instead of scrambling through jumbled memories of names and the shape of structures, students can use a step-wise approach to organise the recall of facts. This chapter outlines such an approach, and it predicates the next chapter (Ch. 18) on radiographic anatomy.

The lumbar spine

It is the lateral view of this column that introduces the next level of detail. The vertebrae are stacked in a curved fashion, forming the lumbar lordosis (Fig. 17.1) A feature of reference in this column is that, most often, the third lumbar vertebra is the most horizontal. Higher vertebrae tilt forwards and upwards; lower vertebrae tilt forwards and downwards. Students able to invoke detail will recall that the average L1–S1 lordosis angle is about 70°, which dictates how curved the lordosis should be.

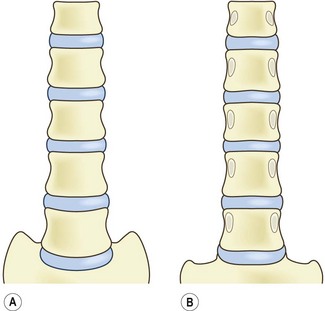

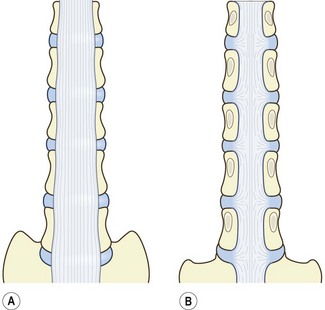

In an anterior view, there is nothing remarkable about this column. The vertebral bodies appear as rectangles, separated by their discs (Fig. 17.2A). Similarly, in a posterior view the column of vertebral bodies is unremarkable. The one new feature is that the posterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies are marked by the origin of the pedicles (Fig. 17.2B).

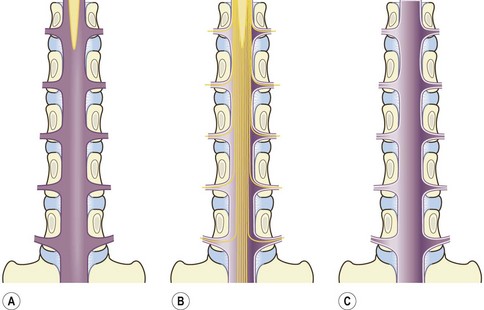

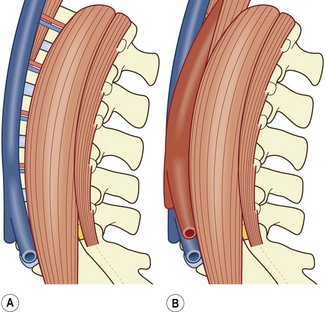

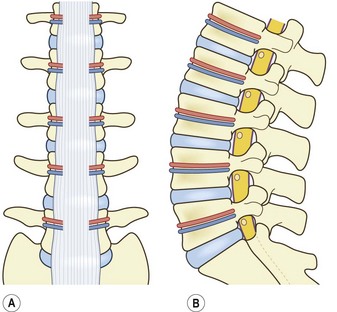

The next layer of reconstruction, in the anterior view, introduces the anterior longitudinal ligament (Fig. 17.3A). Correspondingly, in the posterior view, the posterior longitudinal ligament is introduced (Fig. 17.3B).

Figure 17.3 The lumbar vertebral bodies and their discs, onto which the longitudinal ligaments have been added (cf. Fig. 17.2). (A) Anterior longitudinal ligament. (B) Posterior longitudinal ligament.

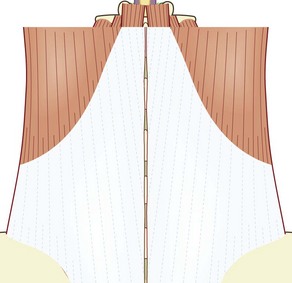

For the time being, the reconstruction focuses on what lies behind the vertebral bodies. This introduces the dural sac, lying in the vertebral canal, and containing the caudal end of the spinal cord, which terminates opposite the L1–2 level (Fig. 17.4A). Hanging from the spinal cord are the nerve roots forming the cauda equina and the lumbar nerve roots passing around the pedicles to their intervertebral foramina (Fig. 17.4B). Eventually, these are enclosed by the posterior half of the dural sac (Fig. 17.4C).

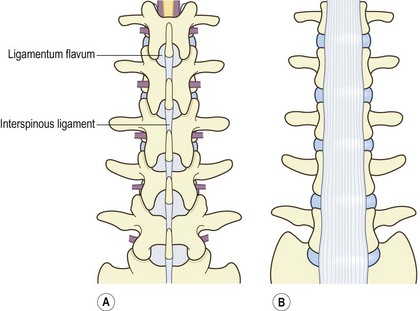

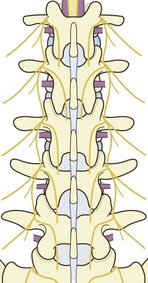

The vertebral canal is then covered by the posterior elements of the lumbar vertebral column (Fig. 17.5A). They consist of the laminae and zygapophysial joints, the transverse processes and the spinous processes. The laminae are joined by the ligamentum flavum, while the spinous processes are joined by the interspinous ligaments. At this stage of the reconstruction, the anterior view has changed little. The transverse processes are the only posterior elements evident in an anterior view. They are seen projecting laterally behind the vertebral bodies (Fig. 17.5B).

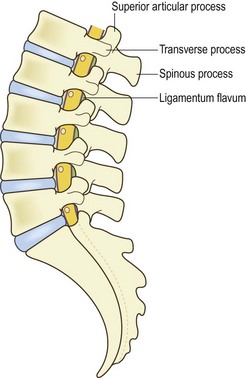

A lateral view of this stage of reconstruction shows the posterior elements projecting behind the vertebral bodies, and enclosing the dural sac; the lumbar spinal nerves lie below the pedicles in their intervertebral foramina (Fig. 17.6). In a lateral view, the superior articular processes cover the inferior articular processes of the vertebra above. So, the inferior articular processes are not evident. At typical lumbar levels, the transverse processes project towards the viewer, from the posterior end of the pedicles; but the transverse process of L5 has a large root, which expands across the lateral surface of the L5 pedicle and onto the L5 vertebral body. The boundaries of the intervertebral foramina are the pedicles above and below, the vertebral body and intervertebral disc anteriorly, and the ligamentum flavum and zygapophysial joints posteriorly.

Around the waists of the vertebral bodies run the lumbar arteries and lumbar veins. In an anterior view, their origins and terminals await connection to the aorta and inferior vena cava; but their trunks disappear posteriorly around the vertebral bodies (Fig. 17.7A). In a lateral view, these vessels cross the vertebral body, heading towards the intervertebral foramina and posterior elements (Fig. 17.7B).

Figure 17.7 The lumbar spine, to which the lumbar arteries and veins have been added. (A) Anterior view. (B) Lateral view. (cf. Figs 17.5B and 17.6.)

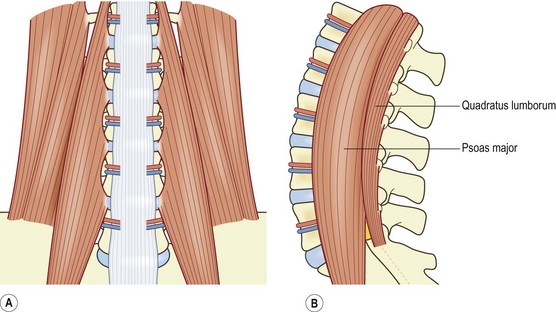

These vessels are covered by the muscles that flank the vertebral bodies, and lie anterior to the plane of the transverse processes. In an anterior view, the quadratus lumborum covers the outer ends of the transverse processes; and the psoas major covers the roots of the transverse processes and the lateral surfaces of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs (Fig. 17.8A). The quadratus lumborum is broad but flat and thin. The psoas major is narrow in the upper lumbar spine but broadens progressively caudally, as more fibres are added to it, and becomes relatively massive at lower lumbar levels. As the psoas enlarges, it bulges over the quadratus lumborum. In a lateral view, the psoas major covers the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs, while the quadratus lumborum is seen in profile, as a narrow flat plane of muscle covering the tips of the transverse processes (Fig. 17.8B).

Figure 17.8 The lumbar spine, to which the quadratus lumborum and psoas major have been added (cf. Fig. 17.7). (A) anterior view. (B) lateral view.

The final stage of reconstruction of the anterior region of the lumbar spine involves placing the great vessels. In the upper lumbar region, the aorta and inferior vena cava are related to the crura of the diaphragm. The left crus attaches to the vertebral column, in a tapering fashion, as far down as the L3 vertebra. The right crus is shorter, reaching only as far as L2 (Fig. 17.9A). With the crura placed, it is a convenient time to introduce the lumbar sympathetic trunks. These issue from the crura and run caudally along the medial border of the psoas major (Fig. 17.9A).

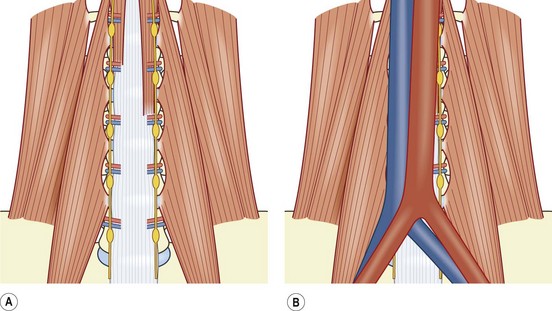

Figure 17.9 An anterior view of the lumbar spine, to which the prevertebral structures have been added (cf. Fig. 17.8). (A) The left crus and right crus have been added, together with the left and right lumbar sympathetic trunks and their ganglia. (B) The inferior vena cava and abdominal aorta have been added.

The inferior vena cava is formed by the convergence of the common iliac veins in front of the L5 vertebra (Fig. 17.9B). It then ascends across the right-hand side of the lumbar vertebral column. At the L1 level, it is pushed forwards by the right crus, so that it can penetrate the central tendon of the diaphragm to reach the heart (Fig. 17.10A). The abdominal aorta starts between the left and right crura, and descends across the left-hand side of the lumbar vertebral column (Fig. 17.9B). It terminates in front of the L4 vertebra by dividing into the common iliac arteries (Figs. 17.9B, 17.10B). As a result of this arrangement, the vascular relations of the lumbar vertebrae differ. At L1, both the inferior vena cava and aorta are present, but the inferior vena cava is being pushed forwards by the right crus. At L2, both great vessels are present, but the inferior vena cava is closer to the vertebral column as the right crus tapers. At L3, the crura have both dissipated, and the two great vessels lie directly in front of the vertebral column. At L4, the inferior vena cava persists, but the aorta divides. Therefore, three vessels lie in front of L4: the inferior vena cava and the two common iliac arteries. At L5, the inferior vena cava is formed. Therefore, four vessels lie in front of L5: the two common iliac arteries and the two common iliac veins.

The branches of the lumbar dorsal rami lie in the deepest layer of the posterior compartment (Fig. 17.11), and enter their respective muscles through their deep aspects. The medial branches enter the multifidus, the intermediate branches enter longissimus thoracis pars lumborum and the lateral branches enter iliocostalis lumborum.

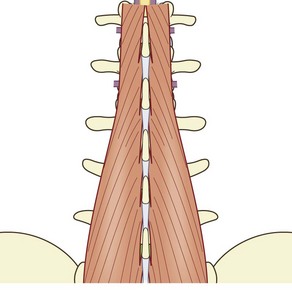

In the upper lumbar region, the multifidus is restricted to the region behind the laminae, but from L3 caudally the muscle expands to assume its insertions into the posterior surface of the sacrum (Fig. 17.12). As a result, it is virtually the only muscle present in the lumbosacral region.

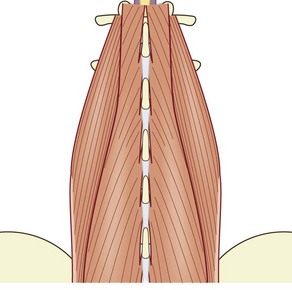

The longissimus thoracis pars lumborum flanks the multifidus. It arises from the lumbar intermuscular aponeurosis, which is anchored to the medial aspect of the posterior segment of the ilium. The muscle fibres insert into the region around the accessory processes of the lumbar transverse processes (Fig. 17.13).

Figure 17.13 A posterior view of the lumbar spine to which the longissimus thoracis pars lumborum and the lumbar intermuscular aponeurosis have been added (cf. Fig. 17.12).

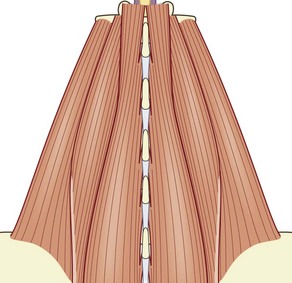

The iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum completes the three major posterior lumbar back muscles. Rising from the iliac crest, it inserts into the distal ends of the upper four lumbar transverse processes (Fig. 17.14).

Figure 17.14 A posterior view of the lumbar spine to which the iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum has been added (cf. Fig. 17.13).

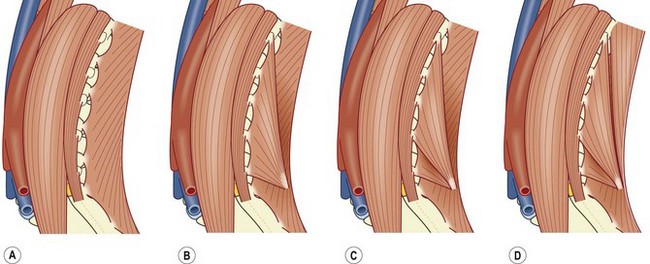

When the three posterior back muscles are viewed from a lateral perspective, certain features become apparent. The multifidus is the most medial of the three muscles. It lies behind the depth of the articular processes and lamina. Its fibres largely run dorsally and cephalad, and are evident throughout the lumbar region (Fig. 17.15A).

The lumbar fibres of the longissimus thoracic run ventrally and cephalad, i.e. contrary to the direction of the fibres of the multifidus muscle (Fig. 17.15B). Furthermore, these fibres fill only the ventral-caudal half of the posterior lumbar region, leaving a space vacant in the dorsal-cephalad half. A similar appearance arises upon the addition of the lumbar fibres of iliocostalis lumborum (Fig. 17.15C). Its fibres, too, run ventrally and cephalad, filling the ventral-caudal half of the region, and leaving vacant the dorsal-cephalad half.

The vacant dorsal-cephalad corner is filled by the lower, thoracic fibres of longissimus thoracis and iliocostalis lumborum (Fig. 17.15D). These fibres arise from the ventral surface of the erector spinae aponeurosis and so, complete the posterior lumbar region when that aponeurosis is finally added to the region. In posterior view, the erector spinae aponeurosis covers all the foregoing muscles, and completes the posterior surface of the lumbar region (Fig. 17.16).

Synopsis

Thus, starting with the column of vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs:

• Anteriorly, we expect to encounter: the anterior longitudinal ligament, the crura of the diaphragm and the aorta and inferior vena cava.

• Laterally, we expect to encounter: the lumbar arteries and veins, covered by the psoas major, which is flanked by the quadratus lumborum.

• Posteriorly, we expect to encounter: the dural sac and its contents, enclosed by the posterior elements of the lumbar vertebra, which in turn are covered by the branches of the dorsal rami, which innervate the three major, posterior back muscles.

• The anterior longitudinal ligament is found throughout the lumbar region.

• The crura occur only at upper lumbar levels, as far as L2 for the right crus, and L3 for the left crus.

• The aorta starts between the two crura, and ends at L4.

• The inferior vena cava starts at L5, and is pushed forwards by the right crus.

• The lumbar arteries and veins are clamped against the vertebral bodies by the psoas major.

• The psoas major is narrow at upper lumbar levels but expands to be massive at lower lumbar levels.

• The quadratus lumborum is broad but flat, and is found only above L5, because it arises from the iliolumbar ligament and transverse process of L5.

• The dural sac contains the spinal cord, cauda equina, and lumbar nerve roots.

• The lumbar nerve roots curve around the inferomedial margins of the pedicles, taking a sleeve of dura mater with them.

• The posterior elements are the pedicles, transverse processes, superior and inferior articular processes, and the spinous processes.

• The boundaries of the intervertebral foramina are the vertebral body and disc, the two pedicles, and the ligamentum flavum and zygapophysial joint.

• The multifidus covers the laminae of the lumbar vertebrae, but expands to cover the back of the sacrum.

• The longissimus thoracis pars lumborum is centred over the lumbar accessory processes and proximal transverse processes.

• The iliocostalis lumborum pars lumborum, aims for the tips of the lumbar transverse processes cephalad of L5.