Reconstruction of the Forehead

Introduction

Reconstructive surgery of cutaneous defects of the forehead may be simple or complex. Several goals must be considered: preservation of motor function (temporal branch of facial nerve) and, if possible, sensory nerve function; maintenance of the aesthetic boundaries of the forehead, including position and symmetry of the eyebrows and the frontal and temporal hairlines; and optimal scar camouflage by placement of scars in or adjacent to the hairline, eyebrows, and relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) whenever possible. This chapter reviews the anatomy of the soft tissue cover of the forehead and the principles of reconstruction of this aesthetic region of the face. The reader is also referred to a number of well-written review articles on forehead reconstruction, from many of which this author has learned and thus improved his expertise in reconstruction of this facial region.1–7

Anatomy

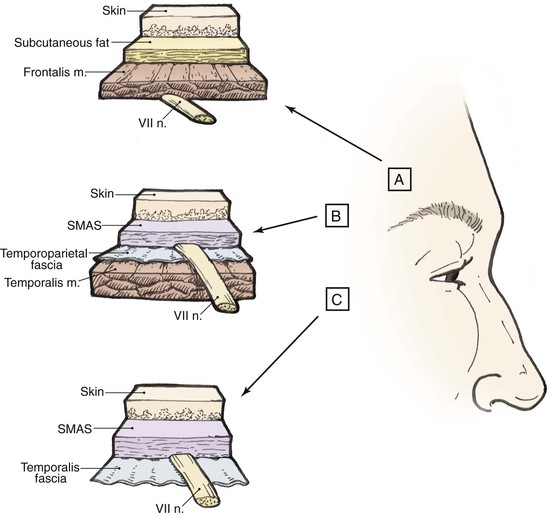

Loss of nerve function, whether motor or sensory, has great consequence to the patient. The motor nerve to the frontalis muscle is the temporal branch of the seventh cranial nerve (Fig. 21-1). This nerve innervates the entire frontalis muscle and is most at risk for injury during flap elevation, not on the forehead, but rather over the zygomatic arch and in the temporal area. The thin skin and subcutaneous tissue in these areas cause the nerve to be close to the skin surface, particularly in thin or aged individuals. Development of flaps in the temporal region may transect the nerve if the flap is not cautiously elevated. On reaching the forehead, the nerve enters the frontalis muscle from its deep surface, and inadvertent transection of the nerve is much less likely. To prevent motor nerve injury, dissection of local cutaneous flaps of the forehead should be in the subcutaneous tissue plane or below the frontalis muscle and above the periosteum of the frontal bone.

FIGURE 21-1 Pathway of temporal branch of seventh cranial nerve in relationship to subcutis, fascia, and muscle. Area C is at highest risk for nerve injury because of proximity of nerve to overlying skin. SMAS, superficial musculoaponeurotic system.

The major sensory nerves of the forehead are the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves, which run with their named arteries. After exiting their foramina in the sub-brow area, they pierce the overlying muscle and extend cephalad in the subcutaneous tissue. Transection of these nerves yields anesthesia distal to the point of injury. The anesthesia may extend posteriorly to the level of the parietal scalp. The numbness perceived by the patient is not only annoying but also potentially harmful because of loss of normal sensory feedback. To prevent sensory nerve damage in dissection of forehead cutaneous flaps, it is essential that the surgeon carefully undermine skin flaps in the superficial subcutaneous tissue plane. For larger flaps developed below the muscle, consideration should be given to placement of incisions peripheral to the path taken by these nerves.

Functional and Aesthetic Considerations

Repair of the skin incision then follows with a layered closure, preferably by intracuticular suturing techniques. A second alternative for correction of eyebrow ptosis is to perform a procedure similar to a direct eyebrow lift, but incisions are made in the midforehead, thereby camouflaging the incisions in the horizontal creases of the forehead skin. Coronal forehead lifts for correction of unilateral eyebrow ptosis are not indicated.

In the last decade, the concept of facial aesthetic regions has greatly simplified and, more important, improved the outcome of facial reconstructive procedures. Facial aesthetic regions have borders that must be maintained to ensure facial symmetry. As a rule, a given aesthetic region is covered with skin that has identical or similar characteristics throughout. If “neighborhood skin” within the same aesthetic region can be recruited to repair a skin defect, optimal aesthetic results may be obtained. The forehead facial aesthetic region is defined peripherally by the juncture lines with the frontal scalp superiorly, the temporal scalp and temple laterally, and the eyebrows and glabella inferiorly (Fig. 21-2). The forehead is somewhat different from other facial aesthetic regions in that it has both an actual and perceived boundary line. Hairstyling can play a major role in forehead visibility. Bangs or a sweeping hairstyle can be used to cover all or part of the forehead. Thus, hairstyling may be used to camouflage a large area of forehead scarring and disfigurement.

FIGURE 21-2 Forehead aesthetic region defined by junction lines with frontal scalp superiorly, temporal scalp and temple laterally, and eyebrows and glabella inferiorly. Reconstruction of forehead skin defects is facilitated by dividing aesthetic region into three units: midline (M), paramedian (P), and lateral (LT). Sources of skin for construction of local flaps for repair of forehead defects include local (L), glabella (G), and temple (T).

Reconstructive Principles

Primary repairs of forehead defects are often possible. There is great variability in the laxity and availability of excess skin on the forehead. Redundant skin is more likely in older individuals and those with sun-damaged skin. Redundant forehead skin may be present in either the horizontal or vertical axis. Skin redundancy can best be determined by pinching and spreading of the forehead skin. Deep forehead furrows may contain relatively large amounts of redundant skin. If adjacent tissue is not adequate for primary wound repair, options include borrowing skin from regional sites (including the temple, scalp, and glabella) and use of skin grafts. Although skin grafts are an easy method of repairing large defects of the forehead, they usually yield suboptimal results because of poor color and texture match with the remaining forehead skin. Split-thickness skin grafts are appropriate for patients with skin cancer who are at high risk for recurrence. The skin graft facilitates accurate surveillance of the tumor site.

Flaps for Forehead Reconstruction

Advancement is the most common design of flaps used for forehead reconstruction. Among the main benefits of advancement flaps are maintaining a natural contour of the forehead, facilitating optimal scar placement in horizontal forehead creases, and usually providing an adequate source of skin for reconstruction. The two major disadvantages of advancement flaps are the requirement for extensive undermining for larger flaps and the need for multiple incisions. Multiple designs for advancement flaps are possible, including unilateral, bilateral, subcutaneous tissue pedicle, and A-T and O-T repairs. Bilateral advancement flaps often take the form of an H-plasty if two parallel incisions are made to create the flaps. If single incisions are used, repair assumes the form of a T-plasty (see discussion in Chapter 6).

Conceptually dividing the aesthetic region of the forehead into three aesthetic units greatly simplifies the thought process and decision-making used for flap selection. The forehead can topographically be divided into the following units: midline; paramedian, extending over the convexity of the forehead from midline to the midpupillary line; and lateral forehead, extending from the midpupillary line to the juncture with the temple (see Fig. 21-2).

Midline Forehead Reconstruction

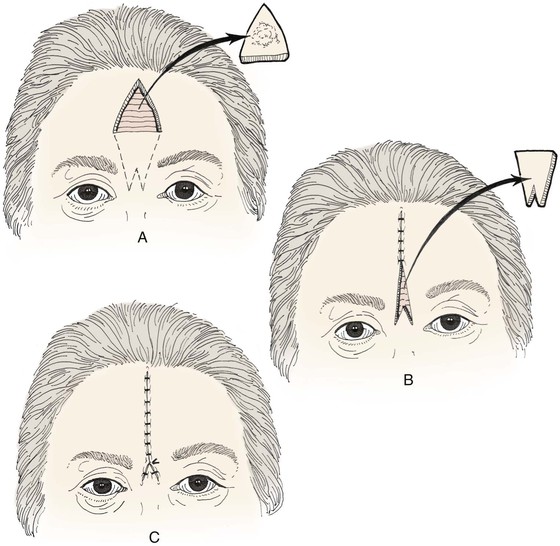

Midline or centrally located cutaneous defects of the forehead can often be closed in a transverse orientation if their vertical height is not too great. Although tissue availability may be sufficient, the medial eyebrows, functioning almost like a free margin, may be elevated to an unacceptable height. For vertically oriented midline or near-midline defects, primary wound closure oriented with the long axis of the wound is often optimal (Fig. 21-3). The linear axis of the closure can be vertically oriented with an expectant acceptable aesthetic result. This approach takes advantage of the anterior extension of the galea and the lack of midline frontalis muscle, which probably accounts for the acceptable scar when wound repair in this area is vertically oriented. Whether primary wound closure is in a vertical or horizontal orientation, advancement of wound margins causes the development of standing cutaneous deformities. These deformities may be excised by a W-plasty or M-plasty when feasible (Figs. 21-4 and 21-5).

FIGURE 21-3 A-D, Preoperative and 3.5-month postoperative views. A 3.5 × 4-cm cutaneous defect of central forehead repaired by bilateral advancement of remaining forehead skin. Patient had previous right paramedian forehead flap to reconstruct nose. No revision surgery performed. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

FIGURE 21-4 A-C, Excision of forehead tumor and W-plasty designed to allow both midline wound closure and camouflage of scars in glabellar creases.

FIGURE 21-5 A, A 3 × 2.5-cm skin defect of central forehead. Primary wound closure planned. Inferior W-plasty and superior M-plasty designed for excision of standing cutaneous deformities. B, Wound closed. Superior standing cutaneous deformity excised in straight line instead of M-plasty. C, Postoperative result at 9 months. No revision surgery performed. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

Vertically oriented primary wound closure of midline cutaneous forehead defects allows extensive undermining beneath the fascia of the frontalis muscle without compromise of motor or sensory nerve function. Although wound closure in a vertical orientation often creates unobtrusive scars, a noticeable drawback is the medial displacement of both eyebrows. Depending on eyebrow visibility, hair density, color, and aesthetic concerns of the patient, medial displacement of the eyebrows may or may not be acceptable and should be discussed with the patient preoperatively. Medial displacement of the eyebrows is a particular dilemma when the defect is in the glabella. Smaller defects (≤2 cm) in this area of the forehead may be repaired with V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled advancement flaps recruiting skin from the central forehead immediately superior to the defect. This has the great advantage of not distorting the relationship of the medial eyebrows by maintaining their natural anatomic position (Fig. 21-6).

FIGURE 21-6 A, A 2 × 2.2-cm cutaneous defect of glabella. V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled advancement flap designed for repair. B, C, Flap incised and in place. This approach prevents medial displacement of eyebrows. D, E, Preoperative and 7-year postoperative views. No revision surgery performed. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

Primary repair of large central forehead defects can be facilitated by intraoperative expansion of scalp and forehead skin (Fig. 21-7). This technique has enabled the author to recruit 1 to 2 cm of additional skin beyond that achievable by wide undermining. A 30-mL Foley catheter is tunneled beneath the frontalis muscle beyond the supraorbital nerve to the lateral forehead and temple regions. The balloon of the catheter is inflated until the skin blanches and is maintained at that volume for 3 minutes and then decompressed for 3 minutes. This cycle is repeated two additional times, with each expansion yielding additional tissue stretch. The stretched tissue gained with intraoperative expansion is often sufficient to close midline defects, which otherwise could not be repaired by primary approximation.

FIGURE 21-7 A, A 5 × 4-cm skin defect. B, Planned tunnel marked extending below frontalis muscle and lateral to supraorbital nerve (SO). Tunnel used to place intraoperative tissue expander for purpose of expanding skin of lateral forehead and temple. C, Foley catheter in place and balloon expanded. D, One week after primary closure of defect with W-plasty.

When intraoperative skin expansion does not provide adequate tissue for primary repair, the use of bilateral rotation flaps is an excellent method of reconstructing sizable upper midforehead cutaneous defects (Fig. 21-8). Flaps are designed so that they are based inferolaterally, and incisions to create the flaps are positioned along the anterior hairline whenever possible to assist with scar camouflage. Repair of midline cutaneous defects with rotation flaps may be accomplished by unilateral or bilateral flaps. Bilateral flaps are best to maintain symmetry because of some lowering of the hairline, which tends to result from closure of the flap donor site. Large flaps should be dissected in the subfascial plane and require transection of sensory nerves extending peripheral to incisions necessary to create the flap. This in turn results in numbness of the anterior scalp. The patient should be informed of this expected outcome preoperatively.

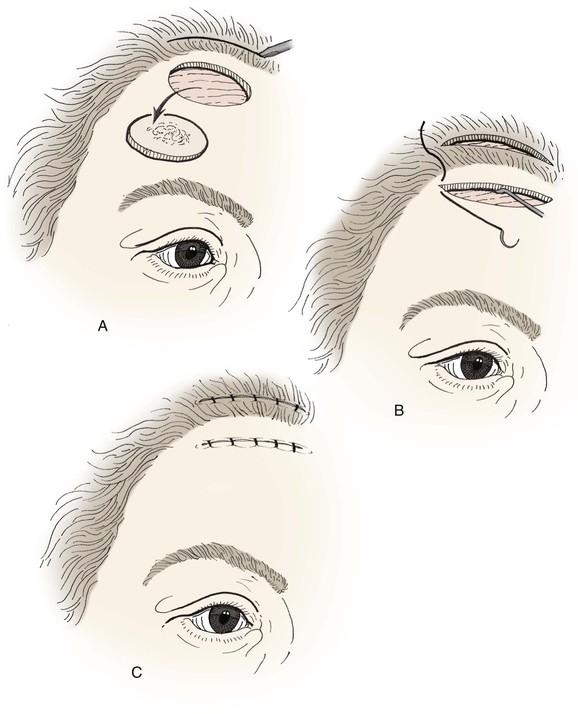

Paramedian Forehead Reconstruction

The degree of bossing of an individual’s forehead is variable, but as a rule, the area from the midline to the midpupillary line tends to be convex. I have labeled this area the paramedian forehead aesthetic unit (see Fig. 21-2). There are fewer good options for repair of cutaneous defects of this portion of the forehead compared with the central part of the forehead. The RSTLs are horizontal in the forehead, and they are the ideal location for placement of incisions. When possible, primary wound closure is best accomplished with a horizontally oriented layered repair to allow maximal scar camouflage (Fig. 21-9). Horizontally oriented primary wound repair is restricted by the vertical height of the defect and thus the degree of eyebrow elevation resulting from wound closure. Eyebrow elevation, in turn, is related to the degree of forehead skin and scalp redundancy and mobility. Eyebrow elevation from horizontally oriented wound repair is also influenced by the size and position of the cutaneous defect. When large defects (more than 3 cm in vertical height) are closed primarily in a horizontally oriented axis, the result is often excessive eyebrow elevation. Defects near the hairline closed in a horizontal orientation have less propensity to elevate the eyebrow compared with defects of similar size located more inferiorly in the proximity of the eyebrow (Fig. 21-10).

FIGURE 21-9 A, A 2.5 × 1.5-cm skin defect of paramedian aesthetic unit of forehead. Horizontally oriented primary wound closure planned with W-plasties designed for excision of standing cutaneous deformities. B, Postoperative result at 6 months. No revision surgery performed. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

FIGURE 21-10 A, A 3.5 × 2-cm cutaneous defect of paramedian forehead. B, C, Wound repaired primarily. D, Postoperative result at 5 years. Excessive elevation of eyebrow is not observed. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

For defects of the paramedian forehead aesthetic unit near the anterior hairline, a bipedicle advancement flap can be useful for repair (Fig. 21-11). An incision is made in the hair-bearing scalp parallel to the superior border of the defect and is carried full thickness through the galea. The bipedicle flap is undermined in all directions and advanced inferiorly to close the forehead defect. The degree of inferior advancement of the flap is dependent on the length of the scalp incision and the position of the defect. The longer the releasing incision, the greater is the mobility of the flap. The secondary defect created behind the frontal hairline can usually be closed by additional undermining below the galea, posterior to the scalp incision. The bipedicle advancement flap is well vascularized and provides a hidden donor site scar but does result in some lowering of the hairline. The larger the defect in the vertical dimension, the greater will be the inferior displacement of the anterior hairline and the greater will be the difficulty in closing the donor site of the flap.

FIGURE 21-11 A, Excision of upper forehead tumor. Incision to create bipedicle advancement flap is full thickness to periosteum posterior to hairline and parallel to long axis of defect. B, C, Advancement of bipedicle flap and closure of defect. Donor defect closed primarily after posterior scalp undermining.

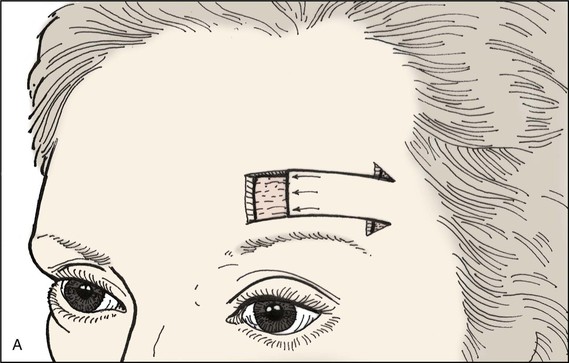

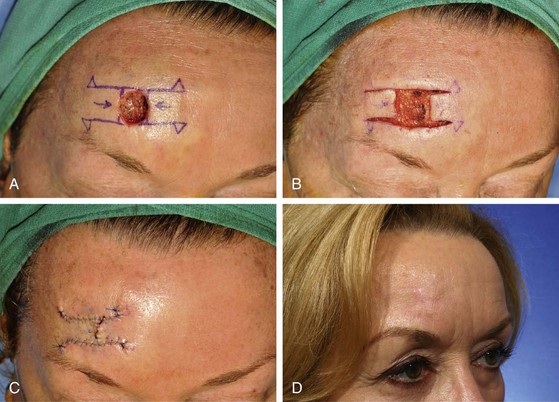

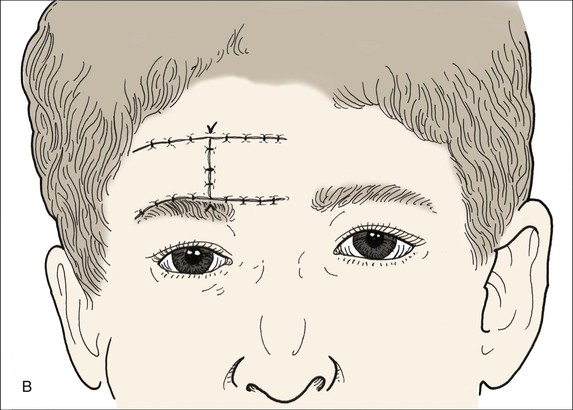

When skin defects of the paramedian forehead are too large for primary repair or have a lengthy vertical component, an advancement flap is usually the preferred method of closure. Incisions are made horizontally, extending laterally from the superior and inferior aspects of the defect. The incisions are limited in length to create a flap with an approximate 4 : 1 ratio of length to width (Fig. 21-12). Most flaps, if they are not subjected to significant wound closure tension, are dissected in the superficial subcutaneous tissue plane. Dissection is in the subdermal plane superficial to the neurovascular bundles while avoiding excess thinning of the flap. The borders of the defect are squared, and standing cutaneous deformities are removed on either side of the flap’s base (see Fig. 21-12). The deformities that develop from advancement can be removed anywhere along the length of the flap so that the scar resulting from excision can be positioned, when possible, in natural skin creases. A particularly good location for placement of the excisions is in glabellar creases (Fig. 21-13). Cutaneous flaps advanced from the lateral forehead and temple skin, where tissue elasticity is greater, may not require removal of standing cutaneous deformities if the rule of halves is used to close the donor site. In such instances, gathering of tissue occurs along the longer border of the wound, and this is remedied by adjustment of the level of suture placement to essentially “sew out” the difference in length between the long and short borders of the wound (see discussion in Chapter 7). Despite this adjustment in suturing, a significant step-off between the surfaces of the flap and the adjacent forehead skin is usually present because of the tautness of the flap. However, even at 1 week postoperatively, this discrepancy is dramatically lessened. A helpful maneuver to camouflage scars is to make the flap slightly wider than necessary if there are nearby natural skin creases in which to hide the incisions.

FIGURE 21-12 A, B, Forehead defect closed by unipedicle advancement flap from lateral forehead skin. Standing cutaneous deformities excised at base of flap.

FIGURE 21-13 A, A 3 × 3-cm paramedian lower forehead cutaneous defect in a 55-year-old man. Unilateral advancement flap marked for wound closure. W-plasty within glabellar creases facilitates removal of standing cutaneous deformity. B, Postoperative result at 3 months. Scar camouflage achieved by placement of incisions in natural horizontal and vertical creases of forehead.

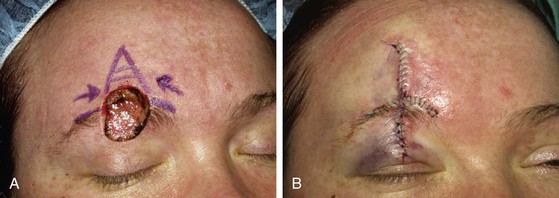

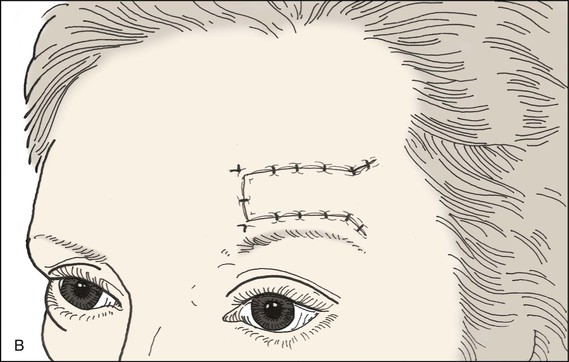

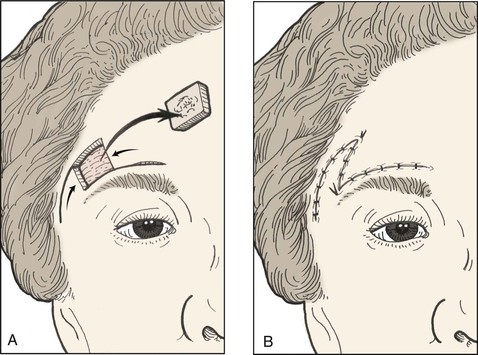

For larger paramedian forehead defects, bilateral advancement flaps are useful for repair (Fig. 21-14). Figure 21-15 demonstrates the use of two advancement flaps to reconstruct a cutaneous forehead defect. Note that residual skin immediately above the eyebrow is removed to develop a laterally based flap with an inferior incision positioned along the border of the eyebrow. The lateral flap is typically longer than the medial flap because of the increased elasticity of lateral forehead skin, which facilitates a greater degree of advancement (Fig. 21-16). Rectangular advancement flaps, whether single or bilateral, are perfect for repair of paramedian forehead defects because of their ability to mobilize adjacent skin, to minimize vertical incisions, to use RSTLs for scar camouflage, and to remove standing cutaneous deformities from a lateral location often in or parallel to crow’s-feet wrinkles (Fig. 21-17).

FIGURE 21-14 A, A 1.5 × 1.5-cm cutaneous defect of forehead. Bilateral advancement flaps (H-plasty) designed for repair. Standing cutaneous deformities marked for excision at base of designed flaps. B, C, Flaps dissected and apposed. Standing cutaneous deformities excised. D, Postoperative result at 6 months. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

FIGURE 21-15 A, B, Tumor excised superior to eyebrow and closed with bilateral advancement flaps (H-plasty). Note additional tissue resection below tumor to allow placement of inferior scar along border of eyebrow.

FIGURE 21-16 A, A 1.5 × 1.4-cm cutaneous defect of forehead. Bilateral advancement flaps (H-plasty) designed for repair. Laterally based flap designed longer than medially based flap because of greater skin elasticity laterally. B, Wound repaired. C, D, Preoperative and 3-month postoperative views. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

FIGURE 21-17 A, A 1 × 1-cm melanoma in situ marked for excision. Bilateral advancement flaps (H-plasty) designed for wound repair after excision. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformities (SCD) marked for excision. B, C, Flaps are dissected in subdermal plane. D, Flaps apposed. Standing cutaneous deformities excised. E, F, Postoperative result at 3 months. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

Most cutaneous defects of the paramedian forehead can be repaired primarily in a horizontal orientation or reconstructed with horizontally oriented unilateral or bilateral advancement flaps. Attempts should be made to avoid vertical, curvilinear, and oblique incisions because they result in scars that are not in RSTLs. This means that vertically oriented primary wound repair and the use of rotation and transposition flaps are to be avoided as a rule. However, these alternatives may be necessary when adjacent scarring from past surgical procedures has limited the ability to use horizontally oriented advancement flaps (Fig. 21-18). Whenever possible, incisions should be positioned in the hairline or along the border of an eyebrow.

FIGURE 21-18 A, A 3 × 2.8-cm paramedian forehead skin defect in a 55-year-old man. Planned incisions marked for laterally and medially based advancement flaps with slight curvilinear borders to parallel forehead creases. Although flaps have some pivotal (rotation design) movement, majority of tissue movement is by advancement. Size of defect and limitations of skin elasticity necessitated modification in design of advancement flaps. B, Flaps in place. C, Postoperative result at 6 weeks.

Lateral Forehead Reconstruction

The lateral forehead aesthetic unit begins at the level of the midpupillary line and extends to the lateral eyebrow, where it joins with the skin of the temple (see Fig. 21-2). Unique to this area is the transition in topography from the convexity of the paramedian forehead to a flat lateral forehead and then slightly concave temple. These surface features along with greater elasticity of lateral forehead and temple skin compared with central forehead skin provide a greater number of reconstructive alternatives. Primary wound closure is often possible with the orientation of the repair parallel to RSTLs (Fig. 21-19). On the lateral forehead, the transverse forehead wrinkles become curvilinear, arch downward, and present excellent locations for placement of incisions. Some individuals have exaggerated transverse skin creases in this area, making them even better for scar camouflage. If creases are not apparent, the patient may better define the location of creases by squinting and elevation of the eyebrow. Primary wound closure of cutaneous defects located at the junction of the lateral forehead and temple may be oriented horizontally so that scars rest in the RSTLs of the crow’s-feet wrinkles (Fig. 21-20).

FIGURE 21-19 A, A 1 × 1-cm skin defect of lateral forehead. Horizontally oriented primary wound closure planned with W-plasties designed for excision of standing cutaneous deformities. B, Postoperative result at 1 week. C, Postoperative result at 4 months. No revision surgery performed. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

FIGURE 21-20 A, A 4 × 3-cm cutaneous defect of temple. Primary wound repair planned. B, Wound repaired. Standing cutaneous deformities removed parallel to crow’s-feet wrinkles. C, D, Preoperative view showing basal cell carcinoma of temple and 1-month postoperative result. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

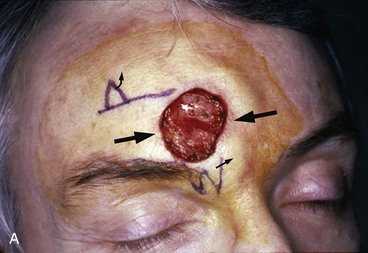

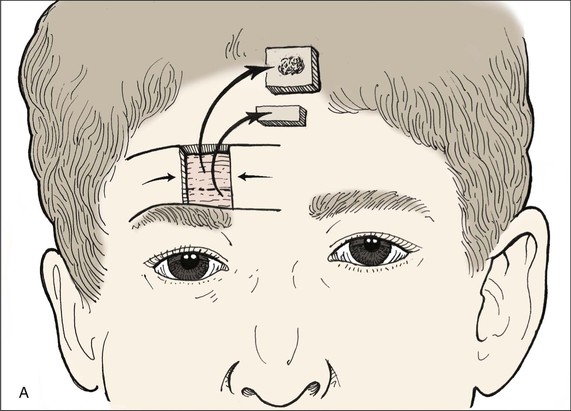

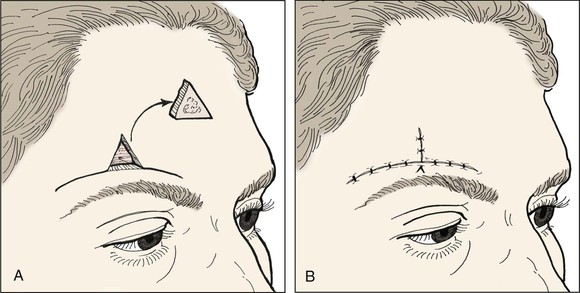

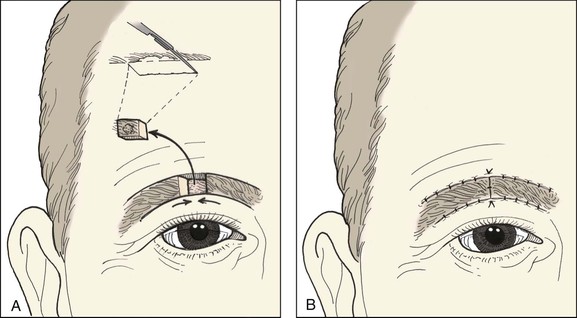

Reconstructive options for repair of skin defects of the lateral forehead often include single or bilateral rectangular advancement flaps. A variation of bilateral advancement flaps effective for repair of skin defects immediately adjacent to the eyebrow in the lateral and paramedian forehead aesthetic units is the O-T or A-T repair. These techniques are discussed in detail in Chapter 9. The technique consists of making horizontal incisions on opposite sides of the base of the defect in RSTLs or along the superior border of the eyebrow (Fig. 21-21). This technique uses two small modified advancement flaps and allows scar camouflage of all but the central vertical closure line. The advancement flaps are modified by using only one incision to create each flap rather than two incisions. Although the primary movement of the flaps is by advancement, some limited pivotal movement also occurs. Burow triangles can be resected adjacent to the eyebrows, or standing cutaneous deformities may be eliminated by the rule of halves.

FIGURE 21-21 A, B, A-T closure of lateral forehead defect with use of transverse forehead creases for scar camouflage.

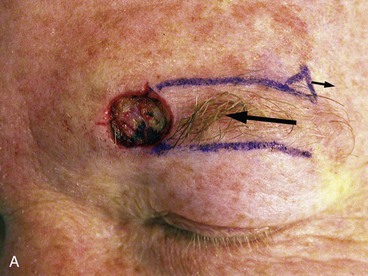

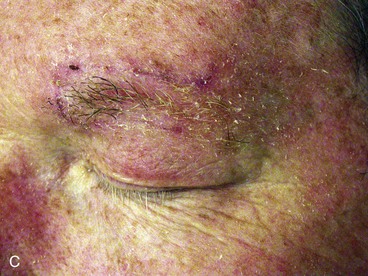

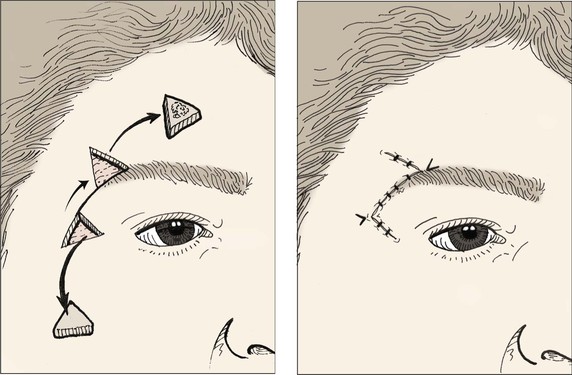

Smaller (≤1.5 cm) cutaneous defects of the lateral forehead skin can often be repaired with an A-T repair with the use of only one flap and one incision (Figs. 21-22 and 21-23). A Burow triangle is removed at the lateral aspect of the eyebrow or farther laterally in the crow’s-feet. The single unilateral incision required to create the flap provides exposure for flap elevation and also is sufficient for flap advancement into the defect. When the defect is located near the eyebrow, enlargement of the wound to the border of the eyebrow allows camouflage of the incision along the superior margin of the lateral eyebrow.

FIGURE 21-22 Advancement flap for repair of lateral forehead skin defect adjacent to eyebrow. Standing cutaneous deformity at base of advancement flap removed from lateral crow’s-feet.

FIGURE 21-23 A, A 1.6 × 1.6-cm lateral forehead skin defect in a 37-year-old man. Advancement flap using single incision designed for repair. Triangles denote locations where standing cutaneous deformity can be removed for maximum scar camouflage. B, Wound closure hiding excision of Burow triangle in lateral eyebrow line and incision to create flap in curvilinear lateral forehead crease. C, Postoperative result at 7 months.

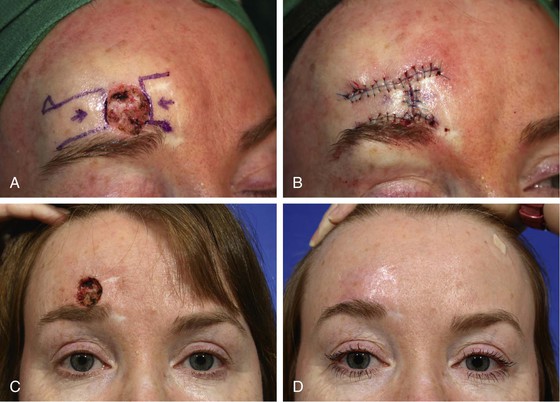

Rotation flaps designed in a number of configurations are often effective in reconstruction of lateral forehead cutaneous defects. In particular, a unilateral rotation flap based inferiorly and laterally and designed so that its curvilinear incision is along the margins of the anterior hairline is an excellent method to reconstruct sizable lateral forehead skin defects that are in proximity to the hairline (Fig. 21-24). Skin excess on the long side of the wound can be sewn out by the rule of halves, or an equalizing Burow triangle can be removed in the hair-bearing skin, which provides excellent scar camouflage. If some of the temporal hair tuft has been lost, the curvilinear incision can be designed upward into the scalp as far as necessary to advance hair into the reconstructed area. The standing cutaneous deformity that forms medially and inferiorly at the pivotal point can be excised sometimes by an M-plasty to prevent excision of portions of the eyebrow or upper eyelid skin.

FIGURE 21-24 A, A 2.4 × 2.1-cm superior lateral forehead skin defect in a 42-year-old man. B, Design of inferiorly based rotation flap with triangular or W-plasty excision of standing cutaneous deformity. C, Wound closed.

O-Z repair of a forehead defect consists of a combination of either two rotation flaps or one rotation flap and one advancement flap. The two-flap technique is useful for repair of defects of the lateral forehead skin. Use of two opposing flaps reduces the size of the flaps necessary for wound repair and recruits skin from two separate areas of the forehead, thus minimizing wound closure tension (Fig. 21-25). The oblique scar that results from wound repair may be acceptable in individuals who have prominent curvature to their lateral forehead creases. In contrast, this method of wound repair is less desirable for forehead defects of the paramedian aesthetic unit because the horizontal creases in this region of the forehead tend not to be curvilinear.

FIGURE 21-25 A, B, Lateral forehead defect repaired with lateral rotation and medial advancement flaps. Portion of scar resulting from wound repair has oblique orientation.

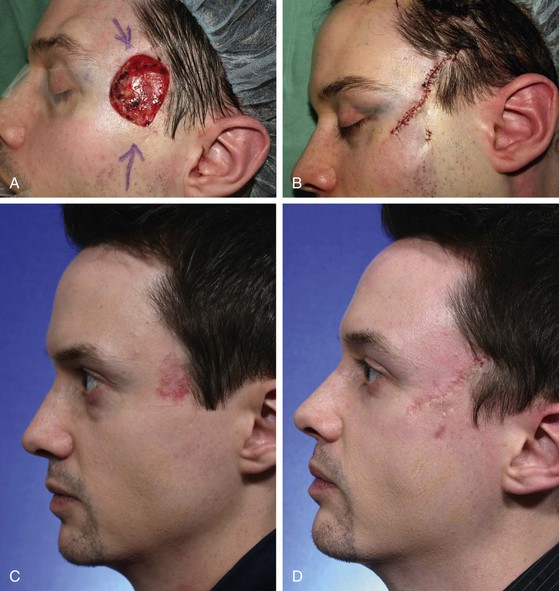

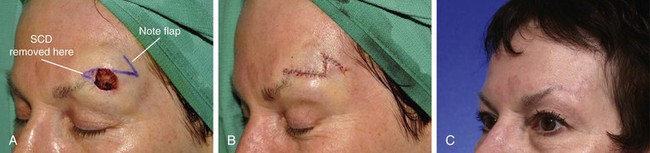

Transposition flaps are commonly used to reconstruct skin defects of the lateral forehead region, taking advantage of the relatively lax skin of the temple. A number of flap designs may be used, including 60° or 30° angled flaps (Fig. 21-26) based superiorly or inferiorly and two transposition flaps of similar or different angles participating in shared wound closure (Fig. 21-27). The scars that result from multiple angulated incisions tend not to be noticeable on the concave surface of the lateral forehead. Although transposition flaps in general are not usually indicated for repair of most forehead cutaneous defects, such flaps can be useful in transferring the entire remaining aesthetic unit of the forehead, especially in the case of the lateral aesthetic unit. An example is shown in Figure 21-28, in which the remaining lateral aesthetic unit was transposed inferiorly to repair a 6 × 5-cm skin defect of the inferior lateral forehead skin and eyebrow. Incisions for the flap were made along the anterior temporal hairline. The donor defect, located at the hairline, was repaired with a single large rotation scalp flap, which enabled a reasonable restoration of the temporal hairline and complete closure of the donor site of the transposition flap.

FIGURE 21-26 A, A 1.3 × 1.2-cm skin defect. The 60° transposition flap designed for repair. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) marked for excision along superior border of eyebrow. B, Wound repaired. C, Postoperative result at 5 months. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

FIGURE 21-27 A, A 2.5 × 2.1-cm lateral forehead skin defect in a 74-year-old man. Two alternative rhombic transposition flaps designed for repair. B, Same defect with 30° angled transposition flap and M-plasty designed. C, Closure accomplished with 30° angled transposition flap. D, Postoperative result at 3 weeks.

FIGURE 21-28 A, B, A 6 × 5-cm full-thickness skin and muscle defect of lateral forehead and temple. C, Full-thickness transposition flap designed to repair defect. Incision for flap made along anterior hairline. D, Large rotation scalp flap used to close donor defect of transposition flap. E, F, Postoperative result at 9 months. No revision surgery performed. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

Eyebrow Reconstruction

The challenges of eyebrow reconstruction are obvious. The goals are to maintain an acceptable position and continuity of the eyebrow. Reconstructive considerations may vary somewhat between men and women because women can pencil in the eyebrow with makeup, eliminating the need for what otherwise might require a complex reconstruction. Small tumors can often be resected from the eyebrow and layered primary wound closure performed in a vertical orientation, maintaining eyebrow continuity. Horizontal closure of eyebrow wounds results in a reduction of the width of the eyebrow, which often is quite noticeable and is not recommended. With vertically oriented primary wound closure, extension of the repair above and below the eyebrow results in scars that are perpendicular to RSTLs and may produce suboptimal results. This can be prevented by repair of intrabrow defects with bilateral rectangular advancement flaps (H-plasty) similar to those described for defects elsewhere on the forehead. The upper and lower incisions to create the flaps are hidden along the inferior and superior eyebrow margins (Figs. 21-29 and 21-30). Incisions for unilateral or bilateral advancement flaps incorporating segments of the eyebrow must be made parallel to the hair shafts (see Fig. 21-29A). This will minimize transection of hair bulbs and subsequent problems with either alopecia or ingrown hairs. Small to medium (<3 cm) cutaneous defects of the eyebrow that extend superiorly to the forehead skin and inferiorly to the upper eyelid skin are best repaired primarily by bilateral advancement or with a T-plasty closure (Fig. 21-31).

FIGURE 21-29 A, B, Bilateral advancement flaps used to repair intrabrow defect. Inset, Proper orientation of incisions parallel to hair shafts to prevent injury to hair bulbs.

Large Cutaneous Defects

Cutaneous defects of the forehead that are too large to close with local flaps may be repaired with a full-thickness skin graft as a preliminary step toward reconstruction. After complete healing of the skin graft, prolonged tissue expansion of the forehead skin adjacent to the graft can be performed in anticipation of removal of the skin graft and repair of the resulting skin defect with an expanded advancement flap. This technique is discussed in detail in Chapter 25. Another alternative is to perform serial excisions of the skin graft with primary wound closure to repair the cutaneous defect left by excising a portion of the skin graft. This requires wide undermining of the entire forehead skin in the subgaleal plane. Sizable cutaneous defects of the forehead can be repaired in this fashion without the use of a permanent skin graft. Depending on the size of the skin defect, two or three serial excisions of the skin graft and advancement of adjacent forehead skin are required. These procedures are performed at 4- to 6-month intervals (Fig. 21-32).

FIGURE 21-32 A, A 6 × 7-cm cutaneous defect of forehead and upper eyelid. B, First-stage reconstruction consisted of full-thickness skin graft of upper eyelid defect and partial closure of forehead wound by bilateral advancement of wound margins. Gauze stent secures skin graft in place. C, Six-month result after first surgical stage. D, Immediately after second surgical stage in which skin graft and forehead scar were excised and the wound was repaired primarily by advancement of wound margins. E, Six months after second surgical stage. (Courtesy of Shan R. Baker, MD.)

Complications

The surgeon must balance patient variables, such as a history of smoking or diabetes, with personal surgical experience to decide when excessive wound closure tension is present. The consequence of misjudgment is a compromised blood supply to the skin with either superficial epidermal or deeper dermal tissue loss. As a rule, these complications are uncommon, particularly when large flaps are designed in an effort to mobilize adequate forehead skin. However, many flaps used for forehead reconstruction of cutaneous defects are elevated in the subcutaneous tissue plane, which increases the potential for bleeding and impaired vascularity. Inspection and then reinspection to ensure a dry field are indicated before wound closure. Despite the reduced vascularity of some flaps and the potential for bleeding, wound infection is not more frequent for repair of skin defects of the forehead compared with other sites on the face.

Alopecia of the eyebrow or scalp hair can result from two causes. The first is improper angulation of incisions causing transection of the hair bulbs during flap elevation. The second is undermining of hair-bearing skin in a plane that is too superficial. This results in injury of the hair bulbs and subsequent alopecia. Neither of these problems should occur when surgeries are conducted by experienced surgeons. Ingrown hairs are often observed after reconstruction of the scalp and, to a lesser degree, of the eyebrow. Despite proper surgical technique, the healing wound and resultant scar may entrap hairs along the incision line and cause both ingrown hairs and milia. Sutures placed by chance into follicular structures may also lead to the formation of sinus tracks with small cysts in the incision line.

Summary

Reconstruction of cutaneous defects of the forehead is not just a matter of wound closure. The reconstructive surgeon must maintain or reestablish the normal aesthetic boundaries of the region while preserving motor and sensory nerve function and maximally camouflaging surgical scars. The surgeon must have a thorough knowledge of the anatomy and function of this region of the face and must understand the principles of soft tissue transfer and movement so that the optimum reconstructive procedure is selected.

References

1. Dzubow, LM. Forehead. In: Dzubow LM, ed. Facial flaps: biomechanics and regional application. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange, 1990.

2. Jackson, IT. Forehead reconstruction. In: Jackson IT, ed. Local flaps in head and neck reconstruction. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1985.

3. Salasche, SJ, Berstein, G, Senkarik, M. Forehead and temple. In: Salasche SJ, Bernstein M, eds. Surgical anatomy of the skin. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange, 1988.

4. Siegle, RJ. Forehead reconstruction. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1991; 17:200.

5. Tromovitch, TA, Stegman, SJ, Glogau, RG. Forehead. In: Tromovitch TA, Stegman SJ, Glogau RG, eds. Flaps and grafts of dermatologic surgery. Chicago: Mosby–Year Book, 1989.

6. Greenbaum, SS, Greenbaum, GH. Intraoperative tissue expansion using a Foley catheter following excision of a basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990; 16:45.

7. Zitelli, JA. Wound healing by secondary intention: a cosmetic appraisal. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990; 16:401.