CHAPTER 20 Recognition and Treatment of Skin Lesions

Epidermal Neoplasms

Seborrheic Keratoses

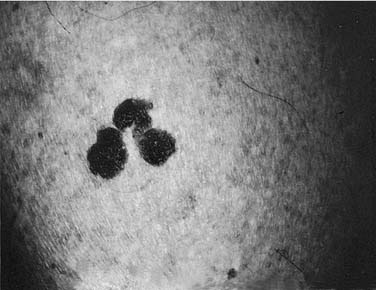

Seborrheic keratoses are common lesions, usually appearing around the fourth decade of life.1 They can be single or multiple and can occur anywhere on the body, with the exception of the palms and soles. Clinically, they are sharply demarcated and slightly raised, appearing as if they were stuck on the skin’s surface (Fig. 20-1). Many have a verrucous surface with a soft, friable consistency; however, others may have a smooth surface. Characteristically, all seborrheic keratoses show keratotic plugs on careful surface inspection. Their color is usually brownish to brown-black, although color can vary from flesh color to deep black. The color within the individual lesion is usually uniform. Lesions can measure from a few millimeters to several centimeters. When subjected to trauma, they can become irritated, thereby causing an inflammatory base and occasional bleeding. Occasionally, seborrheic keratoses are pedunculate, especially on the neck.

The etiology of seborrheic keratoses is unknown, although they may be dominantly inherited. They are benign with no malignant potential, although the appearance of hundreds in rapid “showers” may be a sign of internal malignancy; this is the much-debated Leser-Trélat sign.2 The most common tumor seen with this association is colonic adenocarcinoma. In the head and neck, the most common mistaken diagnosis is melanoma; therefore the pathologist sometimes receives a widely excised seborrheic keratosis that has been mistaken for melanoma. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy before definitive treatment should be performed.

Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra

Dermatosis papulosa nigra is a condition found in approximately 35% of black adults; its onset often occurs during adolescence. The lesions are located predominantly on the face, especially in the malar region, but they may also occur infrequently on the neck and upper trunk. They consist of small (1 to 3 mm), smooth, pigmented, stuck-on appearing, hyperkeratotic papules. Although they have the histologic appearance of a fibroma, many clinicians consider these papules to be a variant of seborrheic keratoses. The treatment of dermatosis papulosa nigra is difficult because of pigmentary problems that occur with the treatment of black skin. Options that have been tried include fine-needle electrosurgery followed by use of a small curette, shave excision, light freezing with liquid nitrogen, and dermabrasion. If the lesions are few, we prefer the first two methods. Cryosurgery can produce spotted hypopigmentation in blacks and should be avoided unless other treatment modalities are not available. Dermabrasion can be of two types: using either a 2-mm wheel or a small cone or pear diamond fraise, the lesions can be removed singly, very quickly, and easily. Dermabrasion can also result in mottled pigmentation after healing, which usually will fade with time. If the lesions are multiple and confluent, total regional dermabrasion may be the treatment of choice for the best cosmetic blend. Judicious use of ablative and pigment-specific lasers can be used to treat these lesions focally; however, meticulous technique is required to avoid pigmentary changes common to this patient population.3

Warts (Verruca Vulgaris)

Warts are common lesions caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is a deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus. Warts are traditionally classified by clinical appearance and location: verruca vulgaris (or common wart), deep hyperkeratotic palmar-plantar; superficial mosaic-type palmar-plantar; verruca plana; epidermodysplasia verruciform; and condyloma acuminatum. Classification may also be based on the genotype of papilloma virus. Hundreds of DNA genotypes have been identified, each with a distinct type-specific antigen, some of which correlate with various benign and malignant conditions.4 The most common facial warts include common warts (including filiform) and flat warts which are most commonly associated with the antigenic serotypes HPV-2 and HPV-3. Clinically, these lesions are hyperkeratotic. The filiform wart is often a pedunculate lesion occurring in isolation on the cheek, nasal tip or columella, or eyelid (Fig. 20-2). Common warts can occur anywhere on the face. Flat warts usually occur in younger patients or on the legs of women who regularly use a razor for shaving; they are small (1 to 2 mm), flat-topped, hyperkeratotic lesions, which can coalesce (Fig. 20-3).

Because the virus survives within cells at the base of the hyperplastic epithelium and within the adjacent normal-appearing skin, eradication of warts can be difficult and recurrences are common. Most common treatments involve destruction of the infected tissue. The filiform wart can be anesthetized at its base and excised with scissors, with the base being lightly curetted and fulgurated under low current; this approach affords the best chance for cure. Filiform warts often are too verrucous and hyperkeratotic to be effectively treated with cryosurgery. Common warts that are thinner can be treated effectively with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, although several treatments are usually needed. Flat warts present a difficult problem. At times, they can be effectively treated with liquid nitrogen. Perhaps the best method is to individually scrape each small wart off of the skin with a small curette, treating, when possible, all of the flat warts in an area at one time. In young children who do not tolerate surgical therapy well, one may use topical tretinoin at a concentration sufficient to produce erythema and irritation in an attempt to stimulate the body’s own immunity against the wart virus. In healthy children, avoiding treatment is often best, because the vast majority of warts spontaneously involute once the patient’s immune system recognizes the virus.5

Related to the poxvirus family is a group of viruses known as the molluscum contagiosum virus family (EM-2). An infection with one of these viruses appears clinically as a variable number of small, discrete, waxy, skin-colored, dome-shaped papillomas, 2 to 4 mm in diameter, with umbilicated centers (Fig. 20-4). Like all viral lesions, they ultimately will involute spontaneously. Histologically, they have a classic appearance of cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which are the so-called molluscum bodies. The best treatment is usually superficial cryotherapy or curettage, as is the case with common warts. Topical therapies, including imiquimod cream, liquid podophyllin, cantharidin, and more recently, injectable candidal antigens, have been successfully used for the treatment of warts and mollusca.

Actinic Keratoses

Actinic keratoses, also called solar keratoses, are precancerous lesions.6 Studies indicate that squamous cell carcinoma will develop in one or more lesions in 5% to 20% of persons with solar keratoses.7–10 They are seen on sun-exposed areas of the skin, usually in persons after the fourth decade of life. They are seen most commonly in fair-skinned individuals who get sunburned frequently. Clinically, these lesions are usually erythematous with adherent scale and show little or no infiltration (i.e., they are very superficial) (Fig. 20-5A). Often, the patient can feel the rough, adherent scale before the lesion is clinically visible. Solar keratoses can also be flesh colored or pigmented. They often do not have a sharp demarcation from surrounding skin and can spread peripherally. Occasionally these lesions develop marked hyperkeratosis, giving a clinical appearance of a cutaneous horn. On the vermillion lip, actinic keratoses are known as solar or actinic cheilitis.

Actinic keratoses lesions are best removed and not watched. The most commonly used method for removing discrete lesions is cryosurgery. Shave excision can also be performed, but it would lead to extensive scarring in areas with numerous lesions. In persons with severe sun damage to the face or with diffuse actinic keratoses, regional treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod, or retinoid creams are effective therapies for an entire region of the body such as the arms, hands, scalp, or face.11,12 Because proper use results in severe irritation, sound patient understanding and education, and physician reassurance are necessary to ensure adequate compliance. Photodynamic therapy, laser resurfacing, dermabrasion, and chemical peels are also effective field therapies.13–16

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy in humans,17,18 accounting for 75% to 80% of new cancers in the United States each year. Depending on the study cited, approximately 86% of lesions occur initially in the head and neck, with 25% of all primary lesions occurring on the nose. Approximately 96% of recurrences are in the head and neck, with 38% being on the nose. Emmett reported that 75.5% of previously untreated basal cell carcinoma found in Australia occurred in the head and neck, 8.4% on the chest and back, and 16% on the arms and legs.19 When looking at recurrent tumors, 91% occurred on the head and neck, 7.5% on the chest and back, and 1.5% on the arms and legs. Similarly, the primary tumor of metastatic basal cell carcinomas is usually found on the head and neck. However, metastasis of basal cell carcinoma is rare, with reports estimating rates of 0.0028% to 0.1%.20–22 In this discussion, we outline the epidemiology and clinical and histologic variations of basal cell carcinoma. Management of head and neck basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas are addressed in Chapter 82.

Basal cell carcinoma, which is more common in men than in women, is seen most frequently in individuals between 40 and 60 years of age. With the aging of the sunbathing generation, however, basal cell carcinomas are occurring with increasing frequency in younger people. Scandinavians and people of Celtic extraction (particularly Irish), who frequently have Fitzpatrick skin type I or type II (sunburn easily), appear to be more prone to basal cell carcinoma than those with more darkly pigmented skin. Although uncommon in blacks, predilection for occurrence on the head and neck is the same as in whites.23 Exposure to sunlight—primarily to the rays in the ultraviolet B spectrum—is the primary risk factor for basal cell carcinoma; this has been shown experimentally and reproduced clinically. The tumor is more common as one approaches the equator and at high altitudes. Basal cell carcinomas occur most commonly on the head and neck areas, with the nasal tip and the nasal ala being the most common; the cheeks and the forehead are the next most common. The left side of the body is more common than on the right, perhaps because of selective sun exposure in individuals whose occupation preferentially exposes the left side (i.e., driving).

Although sun exposure is the primary etiologic agent of basal cell carcinoma, other risk factors include genetics, occupation,24 immunosuppression, ionizing radiation, and the presence of scars. Farmers, sailors, and fishermen, because of their heavy occupationally actinic exposure, have a higher than average incidence of skin cancer. The most common genetic syndromes include nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum.25 The former is an autosomal dominant condition in which basal cell carcinomas arise on any area of the body, with the predilection being toward sun-exposed sites, beginning at an early age and continuing throughout life. These patients also have skeletal abnormalities, including bifid ribs, jaw cysts, frontal bossing, and calcified falx cerebri. Xeroderma pigmentosum is an autosomal recessive disease caused by a defect in DNA repair that leads to the development of basal cell carcinoma and other cutaneous malignancies in response to sun exposure and other carcinogens in childhood and early adulthood.

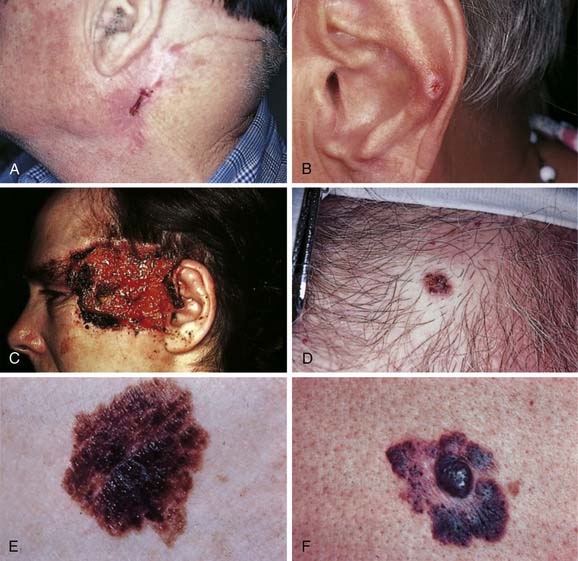

To the trained and observant eye, the clinical recognition of basal cell carcinoma is not difficult. Typically, lesions are nodular with a smooth, raised, translucent or “pearly” border with prominent telangiectasia (see Fig. 20-5D).26 In addition, they may ulcerate and form a crust (see Fig. 20-5C). A typical history involves a pimple-like lesion that bleeds and does not heal. Pruritus is a common early symptom. Basal cell carcinoma may be pigmented (see Fig. 20-5E) yet maintain the clinical features of pearly, translucent borders and telangiectasia. Superficial multicentric basal cell carcinomas are flat and pink with differing, intercommunicating extensions of tumor that may be either scaly or with raised borders.

Other forms of basal cell carcinoma are clinically more subtle, histologically more aggressive, and more difficult to treat. Approximately 20% of primary basal cell carcinomas demonstrate infiltrative growth patterns with significant subclinical disease and high rates of recurrence.27–29 Importantly, many primary tumors demonstrate histologic heterogeneity with subclinical extension.30 Morpheaform basal cell carcinomas (see Fig. 20-5F) present as yellowish plaques, which develop telangiectasia, may ulcerate, and may have a sclerotic or scarlike appearance. The margins are often indistinct. Histologically, this tumor extends subclinical, finger-like projections intradermally, which make complete excision difficult. This tumor has a scarlike, stromal matrix that gives it a fibrous, sclerotic appearance and nature.

Recurrent basal cell carcinomas (Fig. 20-6A) present with varying clinical appearance, depending on the type of initial treatment. It may appear at the edge of a skin graft, within a scar created by electrosurgery, under a scar created by cryosurgery, or as a nodule developing within a suture line. Recurrent basal cell carcinomas are often nodular and accompanied by a morpheaform or sclerotic histologic picture in the deeper portions of the tumor. This picture may represent an aggressive histologic de-differentiation of the tumor, a factor that may partially account for its clinically aggressive behavior and resistance to treatment. The majority of recurrent basal cell carcinomas demonstrate infiltrative patterns in the original tumor; aggressive behavior may be predicted by careful evaluation of histologic features.31

Chondrodermatitis nodularis helicis (see Fig. 20-6B) is an inflammatory disease of underlying helical cartilage that can mimic and be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma. The condition usually results from chronic trauma on the most protuberant portion of the ear. Surgery is the treatment of choice.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common skin cancer and accounts for 10% to 20% of all cutaneous malignancies. Because of their tendency to recur and metastasize, squamous cell carcinomas carry the highest mortality of nonmelanoma skin cancers and account for the majority of deaths due to skin cancer in adults older than 85 years.32 The development of squamous cell carcinoma is multifactorial and involves both environmental and genetic factors. Risk factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma include fair skin; chronic cumulative sun exposure; history of previous skin cancer; age older than 50 years; smoking; chronic inflammatory, infectious, or scarring skin lesions; chemical carcinogens; PUVA; HPV infection; and various genodermatoses. Similar to basal cell carcinomas, the most important factor is ultraviolet radiation. Fair-skinned individuals with longstanding chronic sun exposure, especially those close to the equator and at high altitudes, are at greatest risk. Men are affected two to three times more than women, and multiple cutaneous carcinomas are common.

Whereas the majority of squamous cell carcinomas may be cured if diagnosed and treated early, some behave aggressively with high rates of metastasis. Risk factors associated with high rates of recurrence and metastasis include chronically sun exposed skin, scarred areas in non–sun-exposed skin, tumors greater than 2.0 cm in diameter, recurrent tumors, chronic immunosuppression, poor histologic differentiation, depth of invasion, and perineural involvement.33,34 The true risk of recurrence or metastasis for each variable is unknown; however, associations are clearly established. Clinically, squamous cell carcinomas can be separated into actinically induced and those that arise de novo on non–sun-exposed skin. The former are the more common and are associated with a low incidence of metastasis (<1% in most series). Some studies suggest that de novo lesions have a higher metastatic potential; approximately 2% to 6%. The mucosal variant of the squamous cell carcinoma, seen clinically as carcinoma of the lip, has a metastatic potential of up to 13.7%; therefore these distinctions are important in prognosis.35 The worst prognostic indicator is perineural invasion, which has been shown to metastasize in 47.3% of cases.

Squamous cell carcinoma may present clinically in several ways.36 Thick, scaling, hyperkeratotic plaques may present on the exposed surface of the body, in particular the ear, lip, or nose (see Fig. 20-6C). Lesions may change slowly over a period of time. If the crust is removed, the base is often ulcerated and has a rolled margin. Lesions may also present as a persistent ulcer, particularly in an old scar, or as a superficial multifocal change in generally sun-damaged skin. The latter is often the most difficult lesion to diagnose, requiring several biopsies at different points. Occasionally, a squamous cell carcinoma will become a vegetative nodular lesion; this lesion often has a cystic feel and can ulcerate and progressively enlarge. Often these exophytic lesions have not invaded deeply. They all have a tendency to ulcerate and become more erosive in appearance than a basal cell carcinoma. As with basal cell carcinoma, they can become pigmented (see Fig. 20-6D) and often appear similar clinically to keratoacanthomas, especially when the latter are in the growth phase. However, these lesions usually grow more slowly than keratoacanthomas, thereby allowing for distinction on clinical as well as histologic grounds. When this occurs, biopsy is always indicated. The treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is discussed in depth in another chapter.

Keratoacanthoma is a rapidly growing tumor that presents as an exophytic dome-shaped nodule with central keratin on sun-damaged skin (see Fig. 20-5B). The categorization of keratoacanthoma has been controversial, but it is now thought to be a variant of squamous cell carcinoma. There are some unique features that distinguish it clinically from the common type of squamous cell carcinoma. Keratoacanthomas are characterized by a rapid proliferative phase followed by plateau, then involution. Not all keratoacanthomas, however, involute, and predicting which ones will is difficult. The involution phase can sometimes take up to 1 year. Two rare clinical forms of keratoacanthomas deserve mention. The giant keratoacanthoma can reach 5 cm or more and can cause the destruction of underlying tissues. Eruptive keratoacanthomas often present as many hundreds of characteristic papules that measure 2 to 3 mm in diameter. Metastatic keratoacanthomas have been reported, however, and may represent typical squamous cell carcinoma. Keratoacanthomas can be difficult to treat. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice for most keratoacanthomas, with Mohs micrographic surgery reserved for facial lesions. Because of the involution potential of keratoacanthomas, cytotoxic agents can be used to induce involution. We favor methotrexate at a dose of 12.5 to 25 mg/mL, with approximately 0.5 to 1 mL injected into the lesion at 3- to 4-week intervals. Although complete involution may not occur, it may allow for easier surgical management by reducing the size of the tumor.

Melanocytic Neoplasms

The melanocyte is the pigment-producing cell of the epidermis. However, many tumors of this cell line, which is embryologically from the neural crest, occur in the dermis either by migration or because crest cells fail to reach the epidermis during embryogenesis. The most common of these tumors are nevocellular nevi and melanoma. A wide spectrum of melanocytic nevi and pigmented skin lesions exist, many of which appear similar and can be confused with melanoma.37 This section discusses the clinical manifestations of nevocellular nevi and other melanocytic neoplasms. The presentation, behavior, and treatment of melanoma are discussed elsewhere.

Junctional Nevus

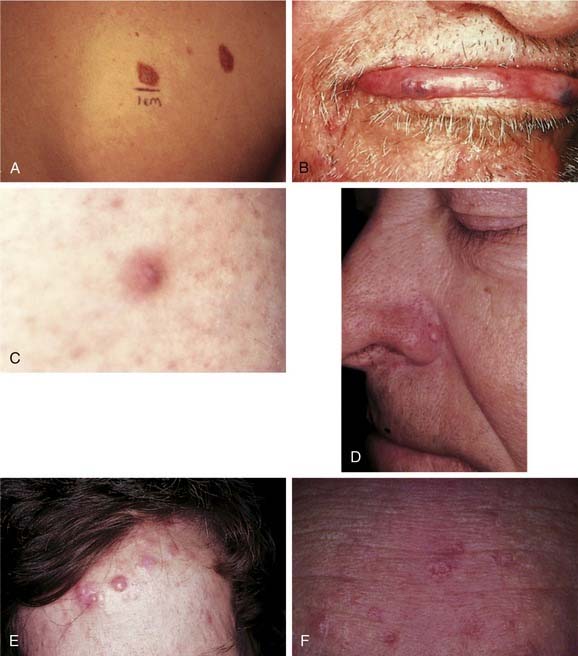

Junctional nevi are tan to brownish macules (flat lesions) of uniform color and smooth border (Fig. 20-7B). Dots of black pigment may be present, but, unlike with melanoma, the normal skin markings are preserved. Lesions vary from a few millimeters to a centimeter or more in diameter. The melanocytes or nevus cells are located at the junction of the epidermis and the dermis (dermoepidermal junction). The lesion can occur anywhere on the body and is the nevus most commonly mistaken for melanoma. When in doubt, one should perform a biopsy of the lesion. Junctional nevi occur anytime after birth and are the common moles found in children before puberty. Their importance lies in their ability to develop into malignant melanoma, although this rarely occurs before puberty. Most junctional nevi remain benign throughout life and can evolve over time into either compound or intradermal nevi. Treatment of these nevi is often dictated by suspicion of melanoma or cosmetic reasons, and usually includes a shave in noncosmetic areas or a fusiform excision with closure in cosmetically important areas. Melanocytes are cold sensitive, and strictly junctional nevi can be removed with deep cryotherapy.

Intradermal Nevus

Intradermal nevi are common mature moles of adults, occurring anywhere on the body but rarely on the palms and soles. It is most common on the scalp or face in adults, varying in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. It may be flat and smooth or raised and warty, pigmented or nonpigmented, sessile or pedunculate (see Fig. 20-7C). It often contains coarse hairs, reflecting the depth within the dermis of the nevus cells. It is benign and rarely becomes malignant. By definition, all of the nevus cells occur within the dermis. This mole is best treated by shave excision when it is pedunculate and hairless. When it is on the head or neck and contains hair, it is necessary to excise this mole using either the punch excision technique or routine excision to remove the complete depth of the hair follicles within the nevus.

Blue Nevus

Blue nevi present as dark blue or black hairless flat or raised lesions that are usually less than 0.5 cm in diameter, indurated, and palpable. The overlying epidermis is remarkably smooth and the outline regular (see Fig. 20-7D). Blue nevi most commonly occur on the head and neck, the dorsa of the hands and feet, and the buttocks. They are more common in women than men and usually undergo very little change after their initial presentation. The treatment of these lesions is excision or observation. The excision must be deep, because the pigment often extends deep into the subcutaneous fat, thereby resulting in the deep blue color of the lesion. Malignant transformation of blue nevi is rare; however, tumors demonstrate highly aggressive behavior, thus these lesions must be carefully evaluated histologically.38,39

Halo Nevus

The halo nevus is a phenomenon usually associated with a junctional nevus in children or adolescents. Most commonly found on the back, it is often a benign-looking brown papular lesion in the center of a well-circumscribed pale white circle of depigmented skin (see Fig. 20-7E). This appearance reflects the body’s rejection of the nevus cells, because an inflammatory response ensues in which the melanocytes of the nevus and those of the immediately surrounding epidermis are destroyed.40 Often, when left alone, these nevi disappear.

Spitz Nevus

Spitz nevus is also known as a juvenile melanoma or a compound melanocytoma. These rapidly growing pigmented lesions occur principally in children, although they can occur in adults. They are usually less than 1 cm in size and are pink or red, or occasionally brown or black. A Spitz nevus may be soft or hard, but is usually dome-shaped and can be either sessile or pedunculated. It can occur anywhere on the body and is often difficult to diagnose clinically. Its main importance is its histologic resemblance to melanoma, with even experienced pathologists having difficulty distinguishing between the two.41 Very few of these nevi, however, progress to malignancy. Treatment of a Spitz nevus is the same as that for an intradermal or compound nevus.

Congenital Nevi

Congenital nevi are usually present at birth; however, in some lesions pigmentation may occur gradually over the first few years of life. In addition to being aesthetically disfiguring, congenital nevi may be associated with a risk of melanoma, neurocutaneous melanocytosis, or malignant tumor, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, among others. Whether this malignant potential is due to the increased number of melanocytes or to some inherited premalignant tendency in the cells themselves is not clear. Congenital nevi are classified according to size with those less than 1.5 cm being small, 1.5 to 20 cm being medium, greater than 20 cm being large, and greater than 50 cm being giant. The precise risk for development of melanoma associated with congenital nevi is difficult to establish; however, risk clearly correlates with size, with the greatest risk being associated with giant congenital nevi. The risk of cutaneous or extracutaneous melanoma associated with small congenital nevi is estimated at 0% to 4.9% and generally occurs at or after puberty. The risk is 4.5% to 10% in large congenital nevi and usually occurs before puberty in this group.42,43 Histologic evaluation of changes within congenital nevi should be evaluated by a dermatopathologist experienced in the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Individuals with large congenital nevi are also at risk for development of neurocutaneous melanosis in which proliferation of leptomeningeal melanocytes may be associated with neurologic disease, structural malformations, and malignant degeneration. Giant axial lesions and those with greater than 20 satellite lesions are at greatest risk.44 The prognosis for patients with symptomatic neurologic disease is poor. Approximately half of patients with neurocutaneous melanosis develop central nervous system melanoma.45

The management of congenital nevi should be individualized based upon nevus size, thickness, location, risk for development of melanoma and other associated conditions, psychological impact, and effects of therapy on the patient and family. Treatment options include surgical excision, dermabrasion, chemical peels, laser therapy, and observation. The timing and choice of therapy should take into consideration the medical, cosmetic, and psychological factors.46,47

Dysplastic Nevus

Dysplastic nevus syndrome, described by Clark and colleagues, is also known as the B-K mole syndrome.48 It consists of the association of familial malignant melanoma, which often occurs in multiple lesions, with “dysplastic nevi” in both the melanoma patient and many of his or her relatives. Dysplastic nevi are usually larger than ordinary melanocytic nevi, ranging from 5 to 15 mm; they present with an irregular border and a haphazard mixture of colors: tan, brown, black, and pink. Centrally, there is often a small, palpable component (Fig. 20-8A). Dysplastic nevi are located on either exposed or nonexposed skin and form throughout adult life, unlike typical nevi that form in earlier years and tend to fade in later years. The idea that a dysplastic nevus may transform itself into a malignant melanoma remains controversial.49

Solar Lentigo

Solar lentigo, also known as actinic lentigo, are keratinocytic pigmented macules that commonly present on the sun-exposed skin of the head and neck.50 They commonly occur as multiple lesions and have been referred to as lentigo senilis. The lesions rarely occur before the fifth decade of life, they slowly increase in size and number, and they form in more than 90% of whites who are older than 70 years old, most commonly on the dorsa of the hands and on the face. They are not infiltrative, and they possess a uniform dark brown color and an irregular outline. Varying in size from minute to greater than 2 cm, they may coalesce to form larger lesions. Malignant degeneration does not occur. These lesions may resemble seborrheic keratoses in clinical appearance, and both conditions are referred to in lay terms as “liver spots.” Solar lentigo, however, are less hyperkeratotic than seborrheic keratoses and have no areas of follicular prominence. It is important to distinguish solar lentigo from melanoma in situ, which may also present as dark brown macules on sun-damaged skin of the head and neck. Solar lentigo can be easily treated with pigment-specific lasers, intense pulsed light devices, cryotherapy, topical retinoids, or chemical peels such as trichloroacetic acid.

Nevus Sebaceus

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn is a common benign congenital lesion that presents as a pebbly, flesh-colored, hairless, well-demarcated lesion of the scalp (see Fig. 20-7F) and other areas of the head and neck. The size varies from 0.5 cm to several centimeters. Off the scalp, the lesion can be linear, closely resembling a linear epidermal nevus. Histologically, these tumors evolve in three discrete stages of growth. In the first few months of life, the sebaceous glands in the lesion are well developed. Thereafter, through childhood, the sebaceous glands are underdeveloped and therefore greatly reduced in size and number; in this phase, the diagnosis may be missed. At puberty, the lesions assume a diagnostic appearance, which is histologically characterized by the presence of large numbers of mature or nearly mature sebaceous glands and by papillomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis. During puberty, various benign and malignant epidermal and adenexal tumors develop in nevus sebaceous. Ten percent to 30% of lesions develop neoplasms during adulthood, usually between the fourth and seventh decades. The most common benign neoplasms include trichoblastoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Of primary importance is the occurrence of basal cell carcinoma in 5% to 7% of sebaceous nevi; numerous other malignant neoplasms have been reported, including squamous cell carcinoma, sebaceous carcinoma, ductal carcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma.51–55 Treatment of nevus sebaceus is complete surgical excision. Complete excision before puberty as a preventive measure had been previously advocated; however, more recently this recommendation has been called into question due to the low incidence of malignant lesions and the ability to identify such changes clinically.56,57 Others have proposed observation with excision of selected lesions, however many prefer excision for aesthetic reasons.58

Cysts

Pilar Cysts

Pilar cysts, which are also known as trichilemmal cysts or wens, are also true cysts; they are clinically indistinguishable from epidermal cysts. The tendency to form such cysts appears to be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. The lining of the cyst differentiates in a manner analogous to that of the outer root sheath of the hair follicle; this fact allows for its differentiation from epidermal cysts. Most pilar cysts occur on the scalp, and they are uncommon before puberty. Multiple cysts are often present. If a pilar cyst ruptures or becomes infected, considerable pain and scarring may result. As with epidermal cysts, the best treatment is complete surgical excision. Proliferating pilar tumors are uncommon tumors thought to originate from pilar cysts and have the potential for malignant transformation. Although these lesions are uncommon, they may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality and must be excised completely.59,60

Dermoid Cysts

Dermoid cysts are rare tumors that are frequently present at birth. They may measure up to 4 cm in diameter, although they are generally less than 2 cm. They may occur anywhere, but they are most common on the face, particularly in the area of the lateral eyebrow, the orbit, and the nose. Dermoid cysts appear to result from the inclusion of embryonic epidermis within embryonal fusion planes. Histologically, these cysts are lined by an epithelium that resembles normal epidermis. They can be differentiated from epidermal cysts by their attachment to adnexal structures, which include hair, sebaceous glands, eccrine glands, and apocrine glands.61 Treatment is by surgical excision. If a dermoid cyst is located over the nasal root, however, care must be taken, because this tumor may be confused with a nasal glioma.62

Steatocystoma Multiplex

Steatocystoma multiplex, an uncommon condition, is often familial, demonstrating an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance. Although lesions can be discovered at any age, they most commonly occur shortly after puberty. The condition presents as multiple 1- to 2-cm cysts, generally located intradermally. They are most commonly found on the anterior chest, but they are also found on the face, forehead, ears, eyelids, and scalp. When punctured, these lesions exude a yellowish, oily fluid and, occasionally, hairs. On histologic examination, these cysts contain a highly corrugated wall of epithelial cells. Embedded within the wall are multiple sebaceous gland lobules, which may be partially responsible for the contents of the cyst. The mode of keratinization of the epithelial lining appears to resemble that of the outer root sheath, and indeed invaginations are often present within the cyst wall that appear similar to hair follicles. Infection with pain and subsequent scarring is a major problem associated with this condition. Treatment is disappointing because of the large number of lesions present, although individual lesions can easily be excised. On the face, cosmetically acceptable improvement has been reported with excision, CO2 laser, dermabrasion, and oral retinoids.63–66

Milia

Milia are small (usually 1 to 2 mm) cysts that differ histologically from epidermal cysts only in their small size. Clinically, they are whitish, smooth globules, most commonly seen on the face. They may arise spontaneously, but they are also frequently present as a result of trauma such as dermabrasion or burns or as a result of bullous diseases. When they arise after trauma or disease as a result of the occlusion of the pilosebaceous unit, they represent a retention cyst. Treatment is the same whether milia arise spontaneously or secondarily and is necessary only for cosmetic reasons; the lesion can easily be shelled out with a hypodermic needle or a comedo extractor. Because they may occasionally number in the hundreds, this treatment can be a considerably tedious chore.67

Mucous Cysts

Mucous cysts are pseudocysts, because no true lining is present; they are also called mucous retention cysts or mucoceles. These lesions are usually located on the mucous surface of the lower lip and are asymptomatic. They are generally less than 1 cm in diameter and, if superficial, may appear slightly bluish and translucent. They appear to be the result of traumatic rupture of the ducts of minor salivary glands. With leakage of the contents into the tissue, an inflammatory process ensues, with the resultant formation of granulation tissues surrounding the cystic space. Mucous cysts may resolve spontaneously or can otherwise be treated by the intralesional injection of low-dose triamcinolone (2.5 mg/mL), excision, or marsupialization.68

Vascular Neoplasms

Cutaneous neoplasms of vascular origin are common and have a variety of presentations. They may be true proliferative tumors, or they may be ectatic vascular malformations present in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. Differentiation may be toward blood vessels, lymph vessels, or both. These lesions may be congenital or arise later in life. Most vascular anomalies are benign. However, they may cause serious psychological or physical problems (because of impingement on important anatomic structures), and, importantly, they may be markers of more serious underlying diseases or syndromes. Vascular anomalies are generally classified as tumors and malformations.69–71 Vascular tumors are characterized by abnormal endothelial proliferation and include infantile hemangioma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, tufted angioma, and pyogenic granuloma. Vascular malformations include lesions with anomalous vessels without an increase in cellular turnover and are further classified according to the predominant vessel type (capillary, venous, arteriovenous, lymphatic). These lesions present at birth and are present throughout life.

Infantile Hemangiomas

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign soft tissue tumor of childhood, occurring in approximately 10% of children. The incidence is greater in females than males and is increased in premature infants. Infantile hemangiomas are uniquely characterized by rapid proliferation during the first months of life followed by slow involution over several years. While most are of little significance, some have the potential for serious complication. The pathogenesis is not known, although positive staining for GLUT-1 (erythrocyte-type glucose transporter protein), which is normally expressed in endothelial cells of placenta, has suggested origination or transplantation from placental cells, although this has not been proven.72

Historically the term hemangioma has been used to describe a variety of vascular anomalies, which led to much diagnostic confusion. The recent identification of specific immunohistochemical markers that distinguish infantile hemangiomas from other vascular malformations has allowed for classification based on biologic markers. The term infantile hemangioma is used exclusively to describe lesions with this distinct presentation and clinical behavior; older terms such as cavernous hemangioma and strawberry angioma have been abandoned.73

Although most hemangiomas are small and innocuous, a minority may present serious medical and psychological complications and may be associated with structural anomalies and neurocutaneous syndromes. The visible presence of hemangiomas and concerns for permanent disfigurement can lead to significant psychosocial stress that can be life altering for the child and family. Nasal tip lesions may distort the nasal anatomy and lead to significant deformity. Hemangiomas in the periorbital area may obstruct the visual axis or compress the orbit, leading to amblyopia and permanent visual loss. Lesions on the oral mucosa and perineum have a propensity for ulceration and bleeding during the rapid growth phase. Hemangiomas in the “beard area” may be associated with airway compromise. A small number of hemangiomas involve a large area of segmental distribution within developmental subunits. Segmental hemangiomas may have associated structural abnormalities with a high risk of serious complications. PHACES syndrome is a constellation of structural anomalies, including posterior fossa malformation, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta, eye abnormalities, and sternal defects that are associated with segmental hemangiomas.74,75

The heterogeneity of presentation of infantile hemangiomas and the potential risk of serious complications introduces complexity to the management of these lesions.76 The majority of hemangiomas involute spontaneously with little consequence, thus treatment is primarily that of “active nonintervention,” which involves close observation during the proliferative phase and familial education and support. Treatment with pulsed dye lasers may be helpful for ulcerated lesions, but has been less useful for deeper lesions. Recent advances in laser therapy using combinations of visible and near infrared wavelengths, however, may have additional benefits for the treatment of hemangiomas. Lesions that threaten to impinge upon important anatomic structures, especially the eye or the respiratory tract, require treatment with systemic corticosteroids. Recalcitrant, life-threatening hemangiomas that are resistant to steroid therapy may require interferon-α 2a or 2b or vincristine chemotherapy, which may have significant adverse side effects. Surgical excision with purse-string closure has been demonstrated to be a valuable intervention for many lesions, particularly those on the face, at all stages of hemangioma development.77

Pyogenic Granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma are common acquired vascular lesions of the skin and mucous membranes. They are most common in children and young adults, or during pregnancy, but may occur at all ages. The pathogenesis is unknown. Pyogenic granuloma most commonly occur at sites of trauma on the distal extremities and the face, and occasionally gingival mucosa, but may present on any part of the body. Histologically, the appearance is that of a polypoid, lobulated mass of newly formed capillary blood vessels surrounded by an edematous stroma.78 Clinically, pyogenic granuloma present as dark red pedunculated nodules often with a surrounding collarette of scale at the base. Pyogenic granuloma are prone to ulceration and bleeding, which often brings the patient to medical attention. Because of their rapid and exuberant growth, these lesions are sometimes mistaken for a malignancy. The differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, metastatic carcinoma, bacillary angiomatosis, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Occasionally, the lesion spontaneously resolves. Lesions associated with pregnancy frequently involute after delivery; most often, however, the lesion must be treated surgically. This treatment is easily accomplished by surgical excision or curettage with electrodesiccation.

Port Wine Stain

Port wine stains may indicate more serious underlying disease associated with several congenital syndromes.71 Sturge-Weber syndrome (leptomeningeal nevus flammeus) is a port wine stain located along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve and angiomas within the meninges, with progressive calcification in these areas. Abnormalities associated with this condition include intractable seizures, developmental delay, and ocular abnormalities such as glaucoma. Increased incidence of Sturge-Weber syndrome is associated with involvement in the distribution of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve, bilateral involvement, and upper and lower eyelid involvement. Klippel-Trénaunay-Parkes-Weber syndrome (osteohypertrophic nevus flammeus) is characterized by hypertrophy of the soft tissues and bones of the lower extremity accompanied by a venous varicosity and an overlying port wine stain.

Telangiectasia

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber Syndrome)

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is a dominantly inherited condition that affects blood vessels throughout the body.79 It is characterized by ectatic vessels of the skin, mucous membranes, and viscera. Often the presenting symptom is spontaneous epistaxis, which may begin during early childhood but more likely appears at puberty or during adult life. Telangiectasia generally begin around and after puberty. The superficial telangiectasia assumes three morphologic forms; the most common lesions are punctate, but they may also be linear or spider-like. The mucous membranes are almost always involved, with lesions occurring on the lips, oral and nasal mucous membranes, nasopharynx, and throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The lesions may ulcerate and frequently bleed. The condition is associated with pulmonary, cerebral, and hepatic arteriovenous malformations. Bleeding may occur from any of the vascular lesions throughout the body and may be fatal. The diagnosis is generally made when the combination of frequent hemorrhagic episodes, vascular ectasias, and a family history is recognized. Genetic testing is available for prenatal diagnosis. Importantly, because catastrophic hemorrhage can occur in children with clinically silent disease, screening imaging for cerebral and pulmonary arteriomalformations is indicated in children who have a family history. Treatment is aimed at control of specific hemorrhages and of anemia, if it arises. Individual cutaneous lesions may be treated by electrocauterization and photocoagulation.

Venous Lake

Venous lakes present as deep blue, cutaneous nodules that occur most frequently on the face, lips, and ears of elderly patients (see Fig. 20-8B). Sometimes called senile angiomas, they are composed of dilated thick- and thin-walled, otherwise normal-appearing vessels. The lesions may thrombose and involute, but frequently they persist. They are of no significance other than a cosmetic nuisance and may be treated with vascular-specific lasers.

Fibroadnexal Tumors

Acrochordon

Acrochordon (skin tag, fibroepithelial papilloma) are extremely common lesions, occurring most often during middle to late life. They are flesh-colored, pedunculate tumors that are generally up to about 2 mm in diameter. They are soft and most commonly occur in flexural regions such as the axillae, the sides of the neck, inframammary areas, and the upper eyelids. The lesions are composed of mostly loose fibrous tissue (similar to that of the superficial dermis), and they are covered by a thin epidermis. No adnexal structures are present. The lesions are easily removed by simple sharp-scissors excision or light electrodesiccation.79

Keloids and Hypertrophic Scars

Keloids and hypertrophic scars are uncontrolled proliferative responses to trauma by the fibrous tissue of the dermis.80 Hypertrophic scar is a thickened scar that does not extend beyond the margins of the original injury, whereas a keloid is an exuberant growth extending beyond the borders of the initial scar. Keloids are most commonly seen in blacks. The epithelium overlying the tumor is frequently thinned and shiny, and the tumor may be tender and pruritic. The areas of predilection for keloids include the sternal area, the shoulders, and the upper back; they are also frequently seen on the earlobes after ear piercing and on the face. These tumors may be flat or extremely protuberant, dome shaped, or bosselated. They are most common in the second and third decades of life, becoming less common with age. Histologically, they present with distinctive keloidal collagen. Hypertrophic scars usually occur on sites of increased skin movement and tension; there is no racial predilection. Treatment of keloid and hypertrophic scars is challenging. Excision of these tumors generally has resulted in regrowth. Some success has resulted from radiation therapy, pressure, cryotherapy, injection of high-potency corticosteroids, interferon and fluorouracil, topical silicone dressings, and pulsed-dye laser treatment. Simple surgical excision is usually followed by recurrence unless adjunct therapies are used.

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

Complete surgical resection of the tumor is the treatment of choice. Lower recurrence rates have been demonstrated by Mohs micrographic surgery with microscopic margin control, providing a distinct advantage over wide local excision.81 Head and neck lesions tend to have high recurrence rates, and may particularly benefit from the use of Mohs surgery techniques. Some success has been demonstrated with pretreatment of advanced and metastatic DFSP with imatinib mesylate, a selective inhibitor of PDGFB kinases, before Mohs surgery, suggesting it may have a primary role in the treatment of DFSP in future.82

Atypical Fibroxanthoma

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a low-grade malignant spindle-cell tumor that most commonly occurs on the sun-exposed areas of the elderly. They are believed to be of fibrohistiocytic origin and to be a superficial variant of a malignant fibrous histiocytoma.83 The lesion is a pink to translucent nodule, generally 1 to 2 cm in diameter. Ulceration is not uncommon. Clinically these tumors may be mistaken for several different types of malignancies, including basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, and melanomas. The risk of metastasis is low, although local and distant metastases have been reported. Histologically, these lesions have a bizarre appearance, with large and atypical epithelioid and spindle cells, and multinucleate giant cells. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Accumulating data suggest lower recurrence rates with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Neurofibromas

Neurofibromas are soft, dome-shaped, flesh-colored lesions that may be located anywhere on the body; they may vary greatly in size, from quite small to large pedunculate lesions. Neurofibromas are derived from the Schwann cells of cutaneous nerves.84 On histologic examination, they present as nonencapsulated, loose, spindeloid tumors. Solitary lesions may be easily excised. These tumors may be indicative of the genetic neurofibromatosis syndrome, which may be associated with severe neurologic problems as well as a risk of malignant degeneration of the tumor. When a neurofibroma is found, a careful search for other manifestations, which include café-au-lait spots and axillary freckling as well as a family history, should be carried out to rule out the syndrome.

Angiofibroma

Angiofibroma (adenoma sebaceum) is present as part of the genetic syndrome tuberous sclerosis. The autosomal dominant syndrome has variable expressivity; the finding of even one angiofibroma requires genetic counseling, because the patient may pass on a much more severe form of the disease to offspring.85 Angiofibromas present as small dome-shaped papules, 2 to 3 mm in diameter, that are flesh colored or reddish brown. They are most commonly present on the sides of the nose and the medial cheeks. The original name is a misnomer, because, on histologic examination, no sebaceous components are noted. The tumors are composed mostly of fibrous tissue and have an angioid component. Laser therapy with a 532-nm KTP laser has been shown to be effective treatment with long remission periods, although new lesions develop with time.

Fibrous Papule

The fibrous papule is a common lesion, generally occurring on the nose—especially the alae—in older persons (see Fig. 20-8D). However, it can also be seen on the medial cheeks. These lesions present as small, 0.5-cm, dome-shaped, flesh-colored papules. Although they are rather common, some confusion persists regarding their origin and histologic nature.86 They have been regarded as perifollicular fibromas, involuting melanocytic nevi, angiofibromas, or simply the result of trauma, such as folliculitis or excoriating pimples. Histologically, the lesion presents as a papule that is composed of numerous spindle-shaped and stellate cells, with occasional multinucleate cells present. Once the lesions have grown, they are generally quite stable and may be present for years; they may be treated by excision or curettage and electrodesiccation. They are of no significance unless related to tuberous sclerosis.

Trichoepithelioma

A trichoepithelioma is an uncommon entity that most often presents as small rounded nodules on the cheeks, eyelids, and nose. It appears to be dominantly inherited; however, pedigrees indicate a greater preponderance of affected females. The lesions are skin-colored to slightly pink and gradually increase, with time, in both number and size. A few telangiectatic vessels may be present, and there may be a slightly translucent quality to the lesions, which may lead to confusion with basal cell carcinoma; however, the lesions rarely ulcerate. If ulceration does occur, basal cell carcinoma should be considered. The histologic appearance of these lesions also closely resembles basal cell carcinoma, and distinguishing between the two is often difficult.87 There are basophilic cells similar to those seen in basal cell carcinoma. The cells are arranged in masses, which may have fully keratinized centers. Occasionally the presence of a solitary lesion makes differentiation from basal cell carcinoma somewhat more difficult, and, unless definite differentiation toward hairlike structures is present, the tumor should be treated as a carcinoma. When multiple lesions are present, treatment is difficult because of the large number of tumors. Some success has been obtained with dermabrasion or laser resurfacing of the entire affected area.

Cylindroma

Cylindromas are slow-growing appendageal tumors derived from follicular epithelium. They may assume apocrine phenotype and usually present as solitary pink to red dermal nodules on the head, neck, and scalp. They present predominantly in older women with a 9:1 female-to-male ratio. The presence of multiple cylindromas is associated with the Brooke-Spiegler syndrome,88 in which an autosomal dominantly inherited mutation in the CYLD tumor suppressor gene leads to the development of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and spiradenomas primarily located on the head and neck.89,90 Multiple cylindromas may literally cover the scalp, resulting in a syndrome called “turban tumors” (see Fig. 20-8E). Individual tumors can reach 2 to 3 cm in diameter. Histologically, these tumors are composed of nests of darkly staining epithelial cells surrounded by a narrow band of hyaline material. The solitary lesion must be differentiated from basal cell carcinoma. Surgical excision is the only treatment. When large areas of the scalp are involved, this may be quite difficult and may require grafting. Although usually benign, cylindromas may undergo malignant transformation with subsequent local invasion and metastatic disease.

Hidrocystoma

A hidrocystoma may be either eccrine or apocrine in origin.91 In either case, the tumor usually presents as a solitary lesion and is most frequently seen on the face, especially around the eyelids. The lesion consists of translucent nodules with a firm, cystic consistency. The eccrine hidrocystoma is generally from 1 to 3 mm in diameter, whereas the apocrine hidrocystoma may attain a diameter of 1 cm. Both may have a bluish hue. The two types are distinguishable by histologic criteria. Microscopic examination reveals differing cellular detail and secretion patterns for the two types. In either case, treatment is excision.

Syringoma

Syringomas are benign tumors that originate from the eccrine sweat gland duct; they appear more often in women than in men.92 Syringomas are most commonly located on the face, with the lower eyelids being the most common site. They generally occur in adolescence or early adulthood and may be eruptive or occur in crops. They present as small 1- to 5-mm papules that are usually flesh colored but may be slightly translucent or yellowish. They may resemble trichoepitheliomas, but their location and histology help differentiate them. Histologically, these tumors appear as small nests of cystic ductal structures or as solid epithelial strands, many of which may have a characteristic tail-like projection. They are not associated with underlying abnormality. They do not tend to involute, however, and may present a cosmetic problem when located on the face. They can be treated with a pulsed ablative laser (CO2 or erbium) or with light electrocoagulation using a fine epilating needle.

Sebaceous Hyperplasia

Sebaceous hyperplasia occurs mainly on the face, particularly the forehead, and represents benign enlargement of the normal sebaceous gland (see Fig. 20-8F). It is frequently called senile sebaceous hyperplasia, because it is usually seen in older persons.93 One or hundreds of lesions may be present. They may be from 2 to 5 mm in diameter, and there is usually a central umbilication. These lesions are soft and yellowish and must be differentiated from basal cell carcinoma. Histologically, they present as hyperplastic sebaceous lobules that are otherwise normal in appearance. They are only a cosmetic problem; solitary lesions can be easily treated with a shave excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, or cryosurgery. When the lesions are numerous, surgical excision is not warranted. Therapy with systemic 13-cis retinoic acid has also been described.

Xanthelasma

Xanthelasmas present on or close to the eyelids as soft, yellowish, irregular papules. They usually appear in middle age and can affect either sex, and they are not often associated with xanthomas elsewhere on the body. Frequently, they are an isolated finding and do not always signify elevated serum triglyceride levels, although each patient should be examined for the existence of such a systemic problem.94 Histologically, these lesions present as an accumulation of xanthoma cells, which are lipid-laden histiocytes. Treatment is the application of 50% to 65% trichloroacetic acid, light cautery, or excision.

Lipoma

Lipomas are single or multiple benign tumors composed of adipose tissue. They are soft and may be lobulated or rounded and cystic in nature, and they are generally freely movable. Except in rare syndromes, lipomas are nontender. They generally occur on the trunk, but they may also occur on the neck or any other part of the body. Histologically, they present as proliferations of normal-appearing fat cells that may be surrounded by a thin connective-tissue capsule. Single lesions present only cosmetic problems, and they are generally easily excised. Despite attaining sizes of more than 1 inch in diameter, they may often be expressed through a small, 4-mm punch hole.95

Treatment Methods and Biopsy Techniques

Excisional Surgery

The shave biopsy is one of the most commonly performed procedures for cutaneous lesions.96,97 It is a rapid means of removing tissue either as part of therapy or to establish diagnoses. A shave can be performed using various techniques, with the depth of the shave depending on the angle of the blade as it enters the skin. Usually a No. 15 or No. 10 Bard-Parker blade is used. One should remember that the sharpest point of the No. 15 blade is the rounded tip, whereas the No. 10 has its sharpest edge along the belly of the blade. The shave should be performed using the sharpest portion of the blade. One of the sharpest blades is the Gillette Blue Blade; it is excellent for shaving lesions. A blade breaker or hemostat can break the Blue Blade into any size or shape desired. The blade can then be held between the thumb and forefinger and flexed, thereby allowing for the performance of a superficial shave in which the blade sculpts along the contour of the surface being excised (e.g., the ala of the nose or the helix of the ear). Hemostasis can then be achieved with aluminum chloride. Monsel’s solution (ferric subsulfate) should be avoided on the face or cosmetic areas because of the ability of macrophages to phagocytose the iron, thereby causing a tattoo.

Laser Surgery

The use of lasers in surgery and medicine has rapidly advanced in recent decades and continues to play an important role in the treatment of many cutaneous neoplasms on the head and neck. Innovations in optical technology have allowed for improved therapeutic efficacy and safety and the ability to treat patients with an increasing number of medical and aesthetic indications. Advances in visible and near infrared lasers and broadband light sources, including the development of longer pulse durations, broader spectrums, and combined wavelengths, continue to improve the treatment of numerous benign vascular and pigmented lesions. Far infrared lasers including CO2 and erbium:YAG lasers remain a useful tool for the safe and effective treatment of numerous benign epidermal lesions, and can be the treatment of choice for some premalignant epidermal lesions, including actinic keratoses and actinic chelitis.98,99 They may have a role in the treatment of some in situ carcinomas, although they may be less suitable without the evaluation of tissue margins. The basic principles of laser surgery are discussed in detail in Chapter 3; specific use of lasers used to treat vascular lesions is discussed in Chapter 201.

Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:979.

Anwar J, Wrone DA, Kimyai-Asadi A, et al. The development of actinic keratosis into invasive squamous cell carcinoma: evidence and evolving classification schemes. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:189-196.

Emmett AJ. Surgical analysis and biological behaviour of 2277 basal cell carcinomas. Aust N Z J Surg. 1990;60:855-863.

Farvolden D, Sweeney SM, Wiss K. Lumps and bumps in neonates and infants. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:104-116.

Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;5:353-370.

Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations. Part II: associated syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:541-564.

Glogau RG. The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:S23-S24.

Haggstrom AN, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:S50-S52.

Huether MJ, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of spindle cell tumors of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:656-659.

Johnson TM, Rowe DE, Nelson BR, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin (excluding lip and oral mucosa). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(3 Pt 2):467-484.

Jones MS, Maloney ME, Billingsley EM. The heterogenous nature of in vivo basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:881-884.

Kauvar A, Hruza G. Principles and Practices in Cutaneous Laser Surgery. Boca Raton, FL: Informa Healthcare; 2005.

Leffell DJ, Brown MD. Manual of Skin Surgery: A Practical Guide to Dermatologic Procedures. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1997.

McArthur GA. Molecular targeting of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a new approach to a surgical disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:557-562.

Miller DL, Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States: incidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(5 Pt 1):774.

Mulliken JB, Rogers GF, Marler JJ. Circular excision of hemangioma and purse-string closure: the smallest possible scar. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1544-1554.

Robinson JK. Fundamentals of skin biopsy. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1986.

Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CLJr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip: implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976-990.

Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D. Basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2262-2269.

Schaffer JV, Bolognia JL. The clinical spectrum of pigmented lesions. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27:391.

Tromberg J, Bauer B, Benvenuto-Andrade C, et al. Congenital melanocytic nevi needing treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:136-150.

Tyring SK. Human papillomavirus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and host immune response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1 Pt 2):S18-26.

von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1043-1060.

Walling HW, Fosko SW, Geraminejad PA, et al. Aggressive basal cell carcinoma: presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:389-402.

Weinstock MA. Death from skin cancer among the elderly: epidemiological patterns. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1207-1209.

1. Zimmerman MC. Seborrheic keratoses. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:586.

2. Schwartz RA. Sign of Leser-Trélat. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:88.

3. Lupo MP. Dermatosis papulosis nigra: treatment options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:29-30.

4. Tyring SK. Human papillomavirus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and host immune response. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(1 Pt 2):S18-26.

5. Sterling JC, Handfield-Jones S, Hudson PM. Guidelines for the management of cutaneous warts. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:4.

6. Callen JP, Bickers DR, Moy RL. Actinic keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:650.

7. Glogau RG. The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:S23-4.

8. Berhane T, Halliday GM, Cooke B, et al. Inflammation is associated with progression of actinic keratoses to squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:810-815.

9. Anwar J, Wrone DA, Kimyai-Asadi A, et al. The development of actinic keratosis into invasive squamous cell carcinoma: evidence and evolving classification schemes. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:189-196.

10. Satchell Ac, Barnetson R, Halliday G. Cutaneous biology: increased Fas ligand expression by T cells and tumour cells in the progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. B J Dermatol. 2004;151:42-49.

11. Gold MH, Nestor MS. Current treatments of actinic keratosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(Suppl 2):17-25.

12. Hadley G, Derry S, Moore RA. Imiquimod for actinic keratosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(6):1251-1255.

13. Fien SM, Oseroff AR. Photodynamic therapy for non-melanoma skin cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:531-540.

14. Iyer S, Friedli A, Bowes L, et al. Full face laser resurfacing: therapy and prophylaxis for actinic keratoses and non-melanoma skin cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;34:114-119.

15. Stanley RJ, Roenigk RK. Actinic cheilitis: treatment with the carbon dioxide laser. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:230-235.

16. Coleman WP3rd, Yarborough JM, Mandy SH. Dermabrasion for prophylaxis and treatment of actinic keratoses. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:17-21.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Skin Cancer Prevention and Education Initiative Fact Sheet. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/pdf/0607_skin_fs.pdf

18. Miller DL, Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States: incidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(5 Pt 1):774.

19. Emmett AJ. Surgical analysis and biological behaviour of 2277 basal cell carcinomas. Aust N Z J Surg. 1990;60:855-863.

20. von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1043-1060.

21. Malone JP, Fedok FG, Belchis DA, et al. Basal cell carcinoma metastatic to the parotid: report of a new case and review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000;79:511-515.

22. Robinson JK, Dahiya M. Basal cell carcinoma with pulmonary and lymph node metastasis causing death. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:643-648.

23. Mora RG, Burris R. Cancer of the skin in blacks: a review of 128 patients with basal-cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;15:1436-1438.

24. Warshawsky D, Barkley W, Bingham E. Factors affecting carcinogenic potential of mixtures. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1993;20:376-382.

25. Gailani MR, Bale AE. Acquired and inherited basal cell carcinomas and the patched gene. Adv Dermatol. 1999;14:261.

26. Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D. Basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2262-2269.

27. Maloney ME. Histology of basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:545.

28. Walling HW, Fosko SW, Geraminejad PA, et al. Aggressive basal cell carcinoma: presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:389-402.

29. Hendrix JDJr, Parlette HL. Micronodular basal cell carcinoma: a deceptive histologic subtype with frequent clinically undetected tumor extension. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:295-298.

30. Jones MS, Maloney ME, Billingsley EM. The heterogenous nature of in vivo basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:881-884.

31. Lang PGJr, Maize JC. Histologic evolution of recurrent basal cell carcinoma and treatment implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:186-196.

32. Weinstock MA. Death from skin cancer among the elderly: epidemiological patterns. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1207-1209.

33. Johnson TM, Rowe DE, Nelson BR, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin (excluding lip and oral mucosa). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(3 Pt 2):467-484.

34. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CLJr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip: implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(6):976-990.

35. Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CLJr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976-990.

36. Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:979.

37. Schaffer JV, Bolognia JL. The clinical spectrum of pigmented lesions. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27:391.

38. Goldenhersh MA, Savin RC, Barnhill RL, et al. Malignant blue nevus: case report and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:712-722.

39. Granter SR, McKee PH, Calonje E, et al. Melanoma associated with blue nevus and melanoma mimicking cellular blue nevus: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases on the spectrum of so-called ‘malignant blue nevus’. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:316-323.

40. Zeff RA, Freitag A, Grin CM, et al. The immune response in halo nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:620-624.

41. Casso EM, Grin-Jorgensen CM, Grant-Kels JM. Spitz nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 Pt 1):901.

42. Watt AJ, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Risk of melanoma arising in large congenital melanocytic nevi: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1968-1974.

43. Krengel S, Hauschild A, Schäfer T. Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1-8.

44. Marghoob AA, Dusza S, Oliveria S, et al. Number of satellite nevi as a correlate for neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:171-175.

45. Makkar HS, Frieden IJ. Neurocutaneous melanosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2004;23:138-144.

46. Tromberg J, Bauer B, Benvenuto-Andrade C, et al. Congenital melanocytic nevi needing treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:136-150.

47. Marghoob AA, Borrego JP, Halpern AC. Congenital melanocytic nevi: treatment modalities and management options. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2003;22:21-32.

48. Elder DE, Goldman LI, Greene MH, et al. Dysplastic nevus syndrome: a phenotypic association of sporadic cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1980;46(8):1787-1794.

49. Ackerman AB, Mihara I. Dysplasia, dysplastic melanocytes, dysplastic nevi, the dysplastic nevus syndrome, and the relation between dysplastic nevi and malignant melanomas. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:87-91.

50. Ber Rahman S, Bhawan J. Lentigo. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:229.

51. Arshad AR, Azman WS, Kreetharan A. Solitary sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn complicated by squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2007.

52. Kantrow SM, Ivan D, Williams MD, et al. Metastasizing adenocarcinoma and multiple neoplastic proliferations arising in a nevus sebaceus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:462-466.

53. Kazakov DV, Calonje E, Zelger B, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma arising in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathological study of five cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:242-248.

54. Premalata CS, Kumar RV, Malathi M, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma, trichoblastoma, and syringocystadenoma papilliferum arising from nevus sebaceus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:306-308.

55. Miller CJ, Ioffreda MD, Billingsley EM. Sebaceous carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, trichoadenoma, trichoblastoma, and syringocystadenoma papilliferum arising within a nevus sebaceus. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1546-1549.

56. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of a series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:108-118.

57. Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:263-268.

58. Chun K, Vazquez M, Sanchez JL. Nevus sebaceus: clinical outcome and considerations for prophylactic excision. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:538.

59. Carlin MC, Bailin PL, Bergfeld WF. Enlarging, painful scalp nodule: proliferating trichilemmal tumor. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:936.

60. Satyaprakash AK, Sheehan DJ, Sangüeza OP. Proliferating trichilemmal tumors: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1102-1108.

61. Bonavolonta G, Tranfa F, de Conciliis C, Strianese D. Dermoid cysts: 16-year survey. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;11:187.

62. Farvolden D, Sweeney SM, Wiss K. Lumps and bumps in neonates and infants. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:104-116.

63. Schmook T, Burg G, Hafner J. Surgical pearl: mini-incisions for the extraction of steatocystoma multiplex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:1041-1042.

64. Apaydin R, Bilen N, Bayramgürler D, et al. Steatocystoma multiplex suppurativum: oral isotretinoin treatment combined with cryotherapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:98-100.

65. Keefe M, Leppard BJ, Royle G. Successful treatment of steatocystoma multiplex by simple surgery. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:41-44.

66. Lee SJ, Choe YS, Park BC, et al. The vein hook successfully used for eradication of steatocystoma multiplex. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:82-84.

67. Samlaska CP, Benson PM. Milia en plaque. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:311.

68. Tran TA, Parlette HL3rd. Surgical pearl: removal of a large labial mucocele. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(5 Pt 1):760.

69. Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. Vascular tumors and vascular malformations (new issues). Adv Dermatol. 1997;13:375.

70. Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;5:353-370.

71. Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations. Part II: associated syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:541-564.

72. North PE, Waner M, Mizeracki A, et al. A unique microvascular phenotype shared by juvenile hemangiomas and human placenta. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:559-570.

73. Haggstrom AN, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:S50-S52.

74. Frieden IJ, Reese V, Cohen D. PHACE syndrome. The association of posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:307-311.

75. Metry DW, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. A prospective study of PHACE syndrome in infantile hemangiomas: demographic features, clinical findings, and complications. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:975-986.

76. Frieden IJ, Eichenfield LF, Esterly NB, et al. Guidelines of care for hemangiomas of infancy. American Academy of Dermatology Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:631.

77. Mulliken JB, Rogers GF, Marler JJ. Circular excision of hemangioma and purse-string closure: the smallest possible scar. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1544-1554.

78. Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267.

79. Eads TJ, Chuang TY, Fabré VC, et al. The utility of submitting fibroepithelial polyps for histological examination. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1459-1462.

80. Berman B, Bieley HC. Keloids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:117.

81. Huether MJ, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of spindle cell tumors of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:656-659.

82. McArthur GA. Molecular targeting of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a new approach to a surgical disease. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:557-562.

83. Winkelmann RK, Peters MS. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a study with antibody to S-100 protein. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:753.

84. Requena L, Sangueza OP. Benign neoplasms with neural differentiation: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:75.

85. McGrae JDJr, Hashimoto K. Unilateral facial angiofibromas—a segmental form of tuberous sclerosis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:727.

86. Nemeth AJ, Penneys NS, Bernstein HB. Fibrous papule: a tumor of fibrohistiocytic cells that contain factor XIIIa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:1102.

87. Johnson SC, Bennett RG. Occurrence of basal cell carcinoma among multiple trichoepitheliomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(2 Pt 2):322.

88. Brooke HG. Epithelioma adenoides cysticum. Br J Dermatol. 1892;4:269-287.

89. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

90. Massoumi R, Paus R. Cylindromatosis and the CYLD gene: new lessons on the molecular principles of epithelial growth control. Bioessays. 2007;29:1203-1214.

91. Masri-Fridling GD, Elgart ML. Eccrine hidrocystomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(5 Pt 1):780.

92. Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460.

93. Sehgal VN, Bajaj P, Jain S. Sebaceous hyperplasia in youngsters. J Dermatol. 1999;26:619.

94. Bergman R. The pathogenesis and clinical significance of xanthelasma palpebrarum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(2 Pt 1):236.

95. Hardin FF. A simple technique for removing lipomas. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:316.

96. Robinson JK. Fundamentals of Skin Biopsy. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1986.

97. Leffell DJ, Brown MD. Manual of Skin Surgery: A Practical Guide to Dermatologic Procedures. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1997.

98. Kauvar A, Hruza G. Principles and Practices in Cutaneous Laser Surgery. Boca Raton, FL: Informa Healthcare; 2005.

99. Goldberg D. Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology Series: Lasers and Lights. Vol 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006.