Chapter 12 Rationale and indications for surgical treatment

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) and snoring are collectively referred to as sleep-related breathing disorders (SRBD). Although the specific etiology is unknown, SRBD involves repeated partial or complete obstructions of the upper airway during sleep. The obstructions can be due to anatomical or central neural abnormalities. Loss of airway patency may cause sleep fragmentation and subsequent neurocognitive derangements, such as excessive daytime sleepiness.1 The objective of surgical treatment is to alleviate this obstruction and the associated cardiovascular and neurobehavioral sequelae by increasing airway patency.

Tracheotomy was the first therapeutic modality employed to treat OSAS. Although effective, tracheotomy is not readily accepted by most patients due to its morbidity. Sullivan et al. reported the application of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to maintain upper airway patency as an alternative to tracheotomy.2 Because of its efficacy, CPAP is usually the first-line treatment for OSAS.3 Yet, a subset of patients struggle to accept or comply with CPAP therapy.4 Thus, those patients who cannot tolerate medical therapy may be candidates for surgery.

Recognizing that multiple levels of airway obstruction exist in OSAS is essential to achieve a cure. Consequently, the surgical armamentarium has evolved to create techniques which address the specific anatomical sites of obstruction. The surgeon must be willing to treat all levels of obstruction in an organized and safe manner. Therefore, we developed a two-phase surgical protocol (Powell–Riley protocol) to target the specific anatomical sites of obstruction (nasal cavity/nasopharynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx). This protocol was created to minimize surgical interventions and avoid unnecessary surgery, while alleviating SRBD.5,6

2 RATIONALE FOR SURGICAL TREATMENT

The rationale for surgical treatment of the upper airway is to eliminate or minimize the neurocognitive and pathophysiologic derangements associated with OSAS. These neurocognitive derangements are the result of sleep fragmentation and hypoxemia. Patients with excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) may experience emotional, social and economic problems.7 Furthermore, uncontrollable fatigue may predispose a patient to automobile or occupational accidents.8 Morbidity is seen from the associated sequelae of these pathophysiologic derangements such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias and cerebrovascular disease.9,10 Thus, reducing the Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) by 50% is no longer deemed acceptable. Rather, the goal is to treat to cure (elimination of hypoxemia and normalization of respiratory events). Ultimately, the surgeon’s objective is to achieve outcomes that are equivalent to those of CPAP management. Ideally, surgical intervention seeks to improve the quality of life, enhance longevity and reduce the risk of medical morbidity.

3 SURGICAL INDICATIONS

The indications for surgery are listed in Table 12.1. For patients whose AHI is less than 20, surgical treatments may still be an option. Surgery is considered appropriate if these patients have associated EDS which results in impaired cognition or comorbidities as recognized by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (including hypertension, stroke and ischemic heart disease). Consideration may be given to obtaining a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) or the maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT) to determine other etiologies of EDS for those patients whose symptoms are not obviated with CPAP therapy or for those whose symptoms of fatigue seem out of proportion to the severity of their apnea. In this subgroup of patients, surgery is unlikely to be beneficial. Other factors exist which could predict poor surgical outcomes and consequently render a patient to be an unsuitable candidate for surgery.11 These factors are detailed in Table 12.2.

*Surgery may be indicated with an AHI <20 if accompanied by excessive daytime fatigue.

From Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Surgical management of sleep-disordered breathing. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005, pp. 1081–97.

Table 12.2 Contraindications for surgery

From Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Surgical management of sleep-disordered breathing. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005, pp. 1081–97.

4 PATIENT SELECTION

Proper screening and selection of patients for surgery is vital to achieve successful outcomes and to minimize postoperative complications. Because daytime fatigue has numerous etiologies, such as periodic limb movement disorder and narcolepsy, a complete sleep history must be obtained. Furthermore, the preoperative evaluation requires a comprehensive medical history, head and neck examination, polysomnography (PSG), fiberoptic nasopharyngolaryngo-scopy and lateral cephalometric analysis. A thorough review of these data will identify probable sites of obstruction and direct a safe, organized surgical protocol.11

A complete physical exam with vital signs, weight and neck circumference should be performed on every patient. Specific attention is focused in the regions of the head and neck that have been well described as potential sites of upper airway obstruction, such as the nose, palate and base of tongue. Nasal obstruction, which can occur as a result of septal deviation, turbinate hypertrophy, alar collapse orsinonasal masses, can be identified on anterior rhino-scopy. The oral cavity should be examined for periodontal disease and dental occlusion. Examination of the oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal regions includes a description of the palate, lateral pharyngeal walls, tonsils and tongue base. Mallampati and Friedman have proposed standardized grading systems to describe the degree of obstruction caused by these structures.12,13

The lateral cephalogram allows measurement of the length of the soft palate, posterior airway space, hyoid position and skeletal proportions. It is the most cost-effective radiographic study of the bony facial skeleton and soft tissues of the upper airway. Studies have shown the cephalogram to be valid in assessing obstruction, and in fact, it compares favorably to three-dimensional volumetric computed tomographic scans of the upper airway.14 Since the cephalogram is not performed while the patient is sleeping, the degree of obstruction may be underestimated. Therefore, the results of this imaging test should be correlated with the fiberoptic examination.

Preoperative CPAP can alleviate the issues associated with sleep deprivation and may reduce the risk of postobstructive pulmonary edema. Consequently, all patients who are tolerant of CPAP are encouraged to use this modality for at least 2 weeks prior to surgery. In 1988, Powell et al. recommended the use of preoperative CPAP for all patients who have a Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI) greater than 40 and an oxygen desaturation of 80% or less. According to this protocol, the surgeon must consider insertion of a temporary tracheotomy for those patients with a RDI greater than 60 and/or a SaO2 less than 70% who are intolerant of CPAP therapy.15

5 POWELL–RILEY TWO-PHASE SURGICAL PROTOCOL

This protocol has two distinct phases which direct treatment towards the specific sites of obstruction during sleep. The procedures included in each phase are listed in Table 12.3. The rationale for the protocol is to limit unnecessary surgery (Table 12.4). This approach limits postoperative complications, pain and hospital stay. Furthermore, the surgeon’s main objective is to treat to cure. Since it is difficult to predict outcomes, all patients are counseled on the possibility of needing both phases of surgery in order to achieve a cure (Table 12.5). Conservative surgery (phase I) is recommended initially with the plan to re-evaluate the patient with a postoperative PSG in three to four months. Patients have a reasonable expectation to be cured by phase I surgery alone. If incompletely treated, those patients are prepared for phase II surgery. However, there are instances when phase II surgery may be the appropriate initial procedure. A non-obese patient with marked mandibular deficiency and a normal palate may be most appropriately treated with phase II surgery.6

| Phase I |

| Nasal surgery (septoplasty, turbinate reduction, nasal valve grafting) |

| Tonsillectomy |

| Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) or uvulopalatal flap (UPF) |

| Mandibular osteotomy with genioglossus advancement |

| Hyoid myotomy and suspension |

| Temperature-controlled radiofrequency (TCRF)*-turbinates, palate, tongue base |

| Phase II |

| Maxillomandibular advancement osteotomy (MMO) |

| Temperature-controlled radiofrequency (TCRF)*-tongue base |

*TCRF is typically used as an adjunctive treatment. Select patients may choose TCRF as primary treatment.

From Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Surgical management of sleep-disordered breathing. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005, pp. 1081–97.

Table 12.4 Rationales for Powell–Riley surgical protocol

From Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Surgical management of sleep-disordered breathing. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005, pp. 1081–97.

Table 12.5 Definition of surgical responders

*A reduction of the AHI by 50% or more is considered a cure if the preoperative AHI is less than 20.

From Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Surgical management of sleep-disordered breathing. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, eds. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005, pp. 1081–97.

6 RATIONALE FOR SURGICAL PROCEDURES

6.1 NASAL RECONSTRUCTION

Nasal obstruction is often encountered in the form of septaldeviation, turbinate hypertrophy or nasal valve incompetence. The rationale of surgery is to maintain nasal airway patency and minimize mouth breathing. Mouth opening causes a posterior displacement of the tongue into the hypopharyngeal airway with narrowing of the airway. Surgery may consist of septoplasty, turbinate reduction or alar grafting. While nasal reconstruction is unlikely to cure OSAS, it can improve quality of life and potentially reduce the severity of this syndrome. Furthermore, treating the nasal airway may improve a patient’s tolerance of nasal CPAP.

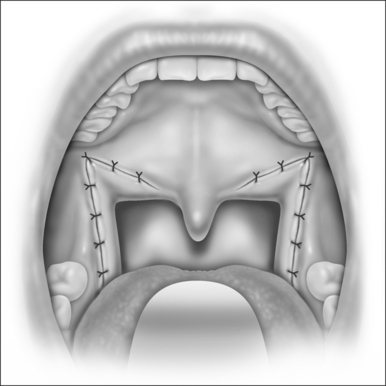

6.2 UVULOPALATOPHARYNGOPLASTY (UPPP)/UVULOPALATAL FLAP (UPF)

The rationale of UPPP is to reposition the redundant soft tissues of the palate and lateral pharyngeal walls. Collapse of the oropharyngeal airway is well documented in patients with SRBD. UPPP is an excellent technique to treat isolated retropalatal obstruction. However, there is often a stigma associated with this procedure due to its intense postoperative pain and variable success rates. Sher et al. documented that UPPP had a cure rate of 39%.16 Unrecognized hypopharyngeal obstruction is thought to be the primary reason for such a high failure rate. If UPPP is performed on patients with obstruction localized to the palate or combined with procedures directed towards other sites of obstruction, the results can be much more gratifying.

The indications and rationale for the UPF are the same as UPPP. The technique was developed to reduce the risk of velopharyngeal insufficiency by using a potentially reversible flap that could be ‘taken down’ if complications arose. Additionally, the UPF is associated with less postoperative pain, as compared to UPPP. The UPF is contraindicated in patients with long and thick palates. In these patients, the flap will be too bulky and could result in a negative outcome.17

6.3 MANDIBULAR OSTEOTOMY WITH GENIOGLOSSUS ADVANCEMENT

The rationale of genioglossus advancement (GA) is to limit the posterior displacement of the tongue into the hypopharyngeal airway during sleep. The genial tubercle, genioglossus muscle and tongue base are advanced anteriorly by creating a rectangular osteotomy in the mandible as described by Riley et al.18 GA is a conservative technique that does not change dental occlusion or jaw position. However, a limitation of this surgery is that no additional room is created for the tongue, in contrast to maxillomandibular advancement.

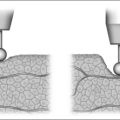

6.4 HYOID MYOTOMY WITH SUSPENSION

The genioglossus, geniohyoid and middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles insert on the hyoid bone. These muscles are vital to maintain the integrity of the hypopharyngeal airway. Thus, the rationale of hyoid suspension is to alleviate hypopharyngeal obstruction by advancing the hyoid complex in an anterior direction. Hyoid suspension may be performed as an isolated procedure or in combination with GA to treat tongue base obstruction.19

6.5 MAXILLOMANDIBULAR ADVANCEMENT OSTEOTOMY (MMO)

MMO is considered phase II treatment and is the only surgery which creates more space for the tongue in the oral cavity. The rationale for MMO is to ameliorate refractory hypopharyngeal obstruction by expanding the skeletal facial framework of the maxilla and mandible. This surgical technique combines a Le Fort I osteotomy and a mandibular sagittal split osteotomy. While the efficacy of MMO has been clearly demonstrated, we typically reserve this surgery for patients who are incompletely treated with phase Isurgery to prevent unnecessary procedures. Furthermore, the success rate of MMO appears to increase when phase I procedures are included in the treatment plan.20,21

7 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

The postoperative management of OSA patients can be challenging. Proper planning and foresight can reduce the incidence of complications. Our two-phase protocol includes a risk management strategy to ensure patient safety.22 Maintaining the integrity of the airway remains the overriding principle of this protocol.

Although airway edema is expected in the postoperative period, every effort must be made to limit swelling. This can be achieved intraoperatively by judicious fluid replacement and meticulous hemostasis. Antihypertensives are administered to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) between 80 and 100 mm Hg. All patients receive 24 hours of intravenous corticosteroid treatment unless medically contraindicated. Furthermore, we strongly encourage patients to use their CPAP immediately after surgery to reduce airway edema.15 When stable, the patients are transferred to the ward.

Antibiotics are administered for 7 days. Fiberoptic evaluation is performed on all patients prior to discharge to ensure a patent airway. Pain is managed at home with hydrocodone and acetaminophen elixir. Requirements for discharge include reasonable pain control, adequate oral intake and a patent airway.22

8 SUCCESS RATE

Clinical response to phase I surgery ranges from 42% to 75%.20,23,24 Our data demonstrate that approximately 60% of all patients are cured with phase I surgery.20 Factors that predict a less successful outcome include a mean RDI greater than 60, oxygen desaturation below 70%, mandibular deficiency (sella nasion point B <75°) and morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] &33 kg/m2).

However, it is imprudent to forego phase I surgery in these patients, since a reasonable percentage may not need more aggressive surgery.20

Patients who are incompletely treated by phase I surgery have persistent hypopharyngeal obstruction. Phase II surgery (MMO) would then be offered to those patients. Maxillomandibular advancement osteotomy has documented success rates &90%.20

1. Schwab RJ, Kuna ST, Remmers JE. Anatomy and physiology of upper airway obstruction. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine. 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:983-1000.

2. Sullivan CE, Issa FG, Berthon-Jones M, et al. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981;1:862-865.

3. Ballestar E, Badia JR, Hernandez L, et al. Evidence of the effectiveness of CPAP in the treatment of sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(5 Pt 1):495-501.

4. Sin DD, Mayers I, Man GC, et al. Long-term compliance rates of CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based study. Chest. 2002;121:430-435.

5. Riley R, Powell N, Guilleminault C, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a surgical protocol for dynamic upper airway reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:742-747.

6. Powell NB, Riley RW. A surgical protocol for sleep disordered breathing. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Ann. 1995;7:345-356.

7. Bonnet MH. The effect of sleep disruption on performance, sleep and mood. Sleep. 1985;8:11-19.

8. Powell NB, Schechtman KB, Riley RW, et al. Sleepy driving: accidents and injury. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:217-227.

9. Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, et al. SDB and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19-25.

10. Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034-2041.

11. Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C. Surgical management of sleep-disordered breathing. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine. 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:1081-1097.

12. Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985;32:429-434.

13. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Joseph NJ. Staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a guide to appropriate treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:454-459.

14. Riley R, Powell N, Guilleminault C. Cephalometric roentgenograms and computerized tomographic scans in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1986;9:514-515.

15. Powell N, Riley R, Guilleminault C, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure, and surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;99:362-369.

16. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

17. Powell NB, Riley RW, Guilleminault C, et al. A reversible uvulopalatal flap for snoring and obstructive sleep. Sleep. 1996;19:593-599.

18. Riley R, Powell N, Guilleminault C. Inferior sagittal osteotomy of the mandible with hyoid myotomy-suspension: a new procedure for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:589-593.

19. Riley R, Powell N, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea and the hyoid: a revised surgical procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:717-721.

20. Riley R, Powell N, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:117-125.

21. Hochban W, Brandenburg U, Hermann PJ. Surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea by maxillomandibular advancement. Sleep. 1994;17:624-629.

22. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea surgery: risk management and complications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:648-652.

23. Johnson NT, Chinn J. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and inferior sagittal mandibular osteotomy with genioglossus advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1994;105:278-283.

24. Lee N, Givens C, Wilson J, et al. Staged surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 35 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:382-385.