26 Rashes and Fever

Clinical Approach

Clinical Approach

The clinical diagnostic approach to rash and fever in the intensive care unit (ICU) depends on whether the rash and fever were community or nosocomially acquired. Community-acquired rash and fever is best approached by considering the distribution/characteristics of the rash.1–5 Rashes are visible clues to infectious or noninfectious disorders. In addition to rash and fever, often associated findings such as history, physical examination, and laboratory abnormalities are keys to the correct diagnosis.1,4,6–8

Nosocomially acquired rashes have more limited differential diagnostic possibilities.6 The clinician should determine whether the rash and fever represents the primary clinical problem or is a superimposed finding unrelated to another process—for example, ICU patients admitted for acute myocardial infarction can develop a drug rash from an antiarrhythmic medication, beta-blocker, diuretic, or sulfa-containing stool softener (Colace).1,3

Acutely ill patients with rash and fever in the ICU should have the benefit of an infectious disease consultation by an experienced infectious disease clinician.1,3 Both community and nosocomial acquired rash/fever are best diagnosed using the clinical syndromic approach; associated clinical findings, not the appearance of the rash per se, are the main determinants of arriving at the correct diagnosis.5,7

Community-Acquired Rash and Fever

Patients admitted to the ICU from the community with rash/fever are best approached by the type/distribution of the rash.2 The degree of fever relative to the pulse rate, and fever pattern are also important diagnostic considerations.3,9

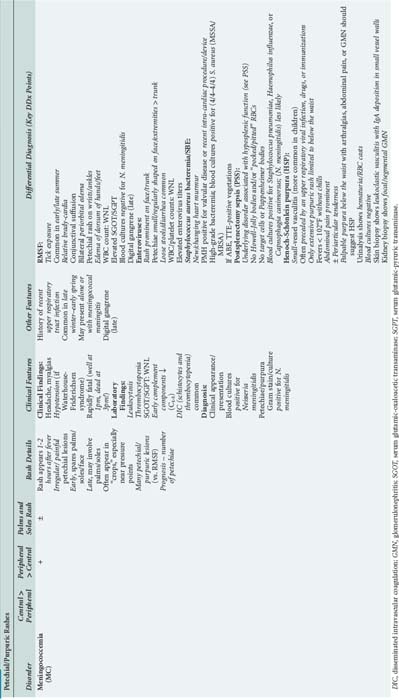

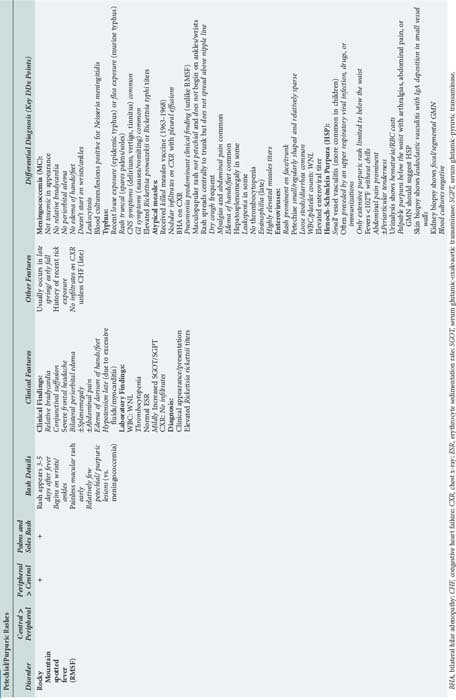

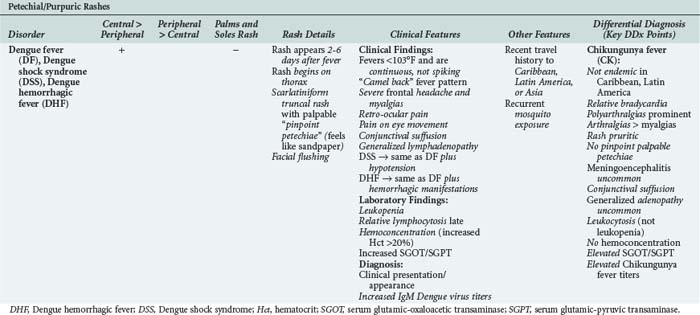

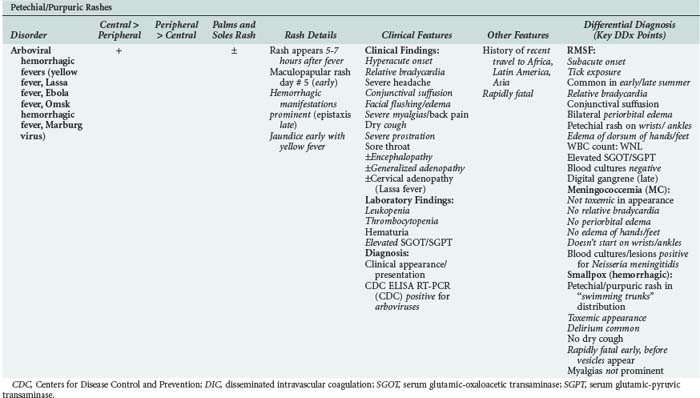

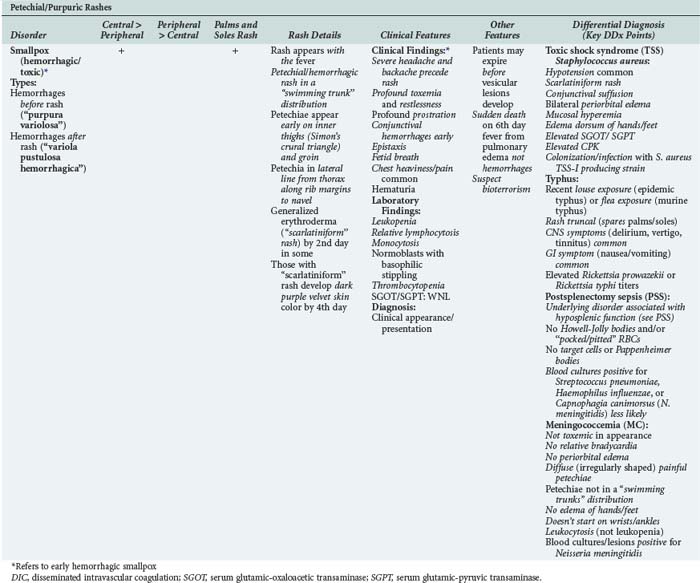

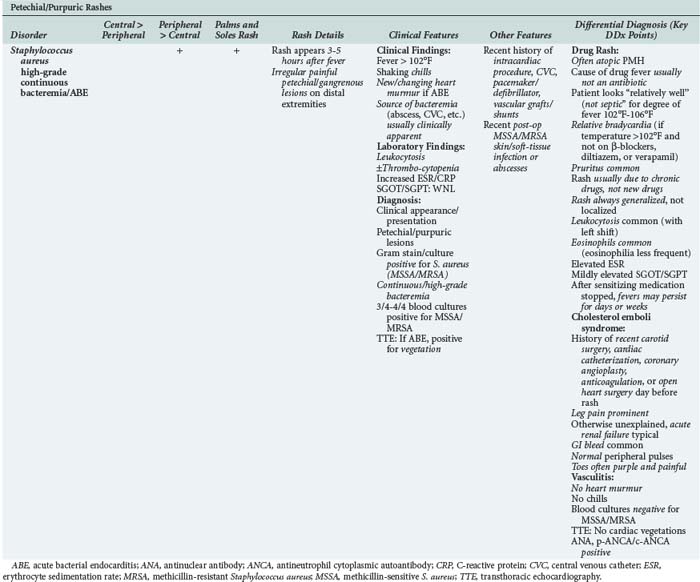

Petechial/Purpuric Rashes and Fever

While petechial/purpuric rashes are common causes of community-acquired rash/fever, petechiae can accompany a variety of systemic infections as well as a variety of noninfectious disorders.10–12 Rash/fever are often potentially life-threatening (e.g., meningococcemia [MC] with or without meningitis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever [RMSF], dengue fever [DF], and arboviral hemorrhagic fevers), and patients should have the benefit of a diagnostic evaluation by an experienced infectious disease consultant.1,4,10,11

The two most common infectious diseases presenting with a petechial/purpuric rash are MC and RMSF. RMSF should be suspected with a recent tick exposure history and/or a characteristic location/distribution of the rash. Importantly, RMSF is the only infectious exanthem that begins on the wrists and/or ankles.13–15 In contrast, the rash of MC is asymmetrical with irregularly shaped painful petechial/purpuric lesions.1,8,11

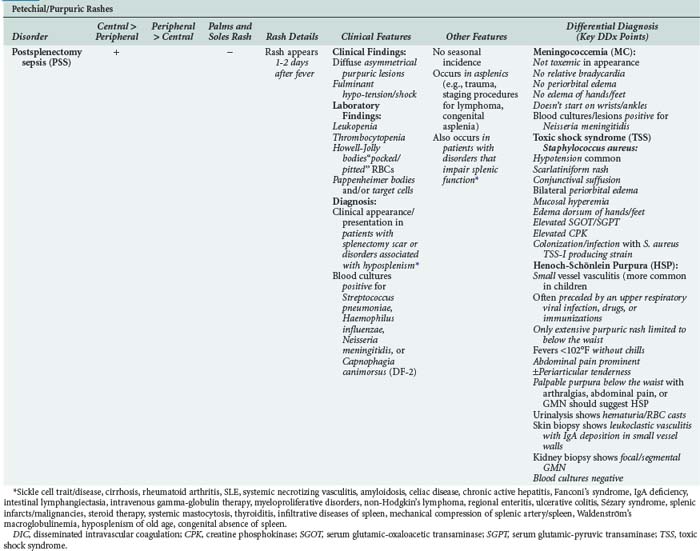

Post-splenectomy sepsis (PSS) can resemble meningococcemia but only occurs in patients with impaired/absent splenic function.1,4,11 Clinicians should be familiar with the disorders associated with diminished splenic function. A key clinical clue to impaired splenic function is the presence of Howell-Jolly bodies or “pocked/pitted” red blood cells in the peripheral smear. The number of Howell-Jolly bodies or “pocked/pitted” RBCs is inversely proportional to splenic function.1,8

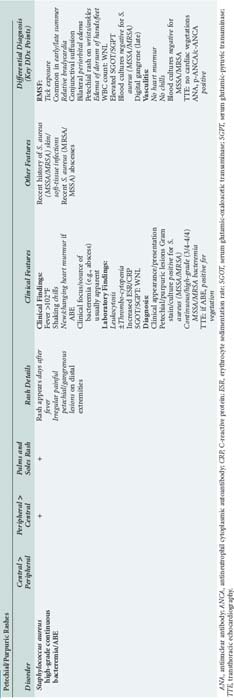

High-grade/continuous Staphylococcus aureus bacteremias (methicillin sensitive/methicillin resistant [MSSA/MRSA]) from abscesses or acute bacterial endocarditis (ABE) are often accompanied by splinter hemorrhages and petechial/purpuric rashes on the distal extremities.1,10,11

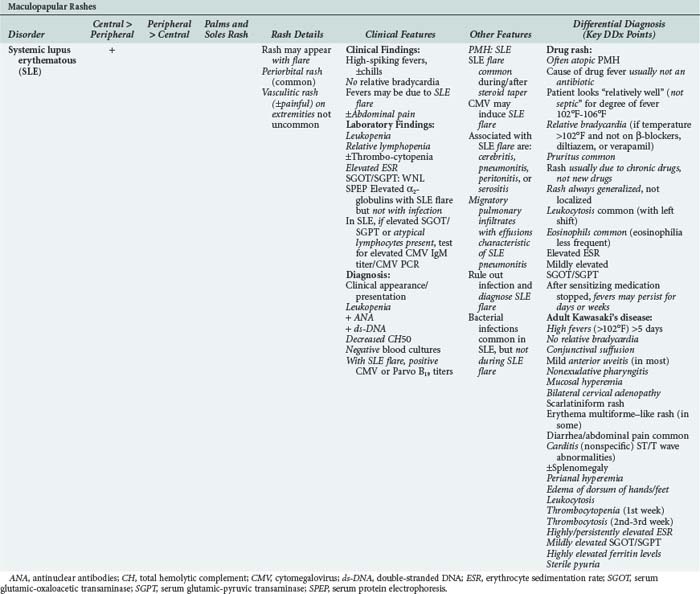

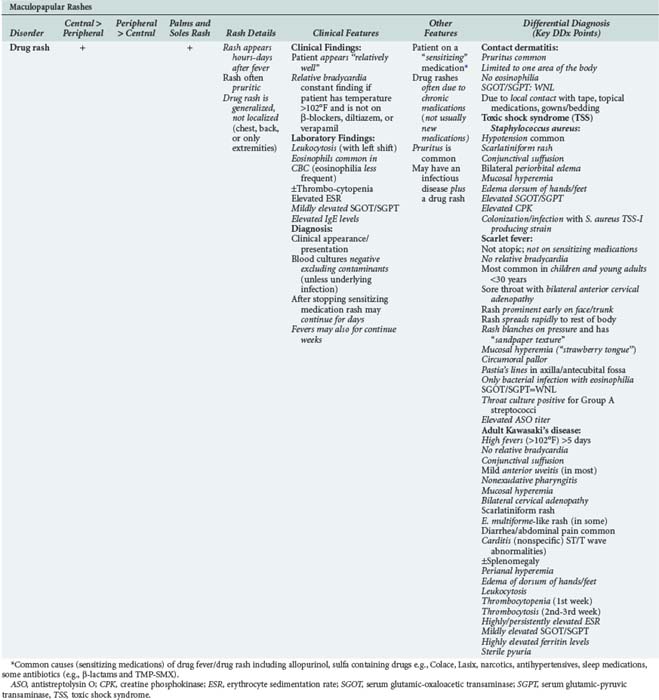

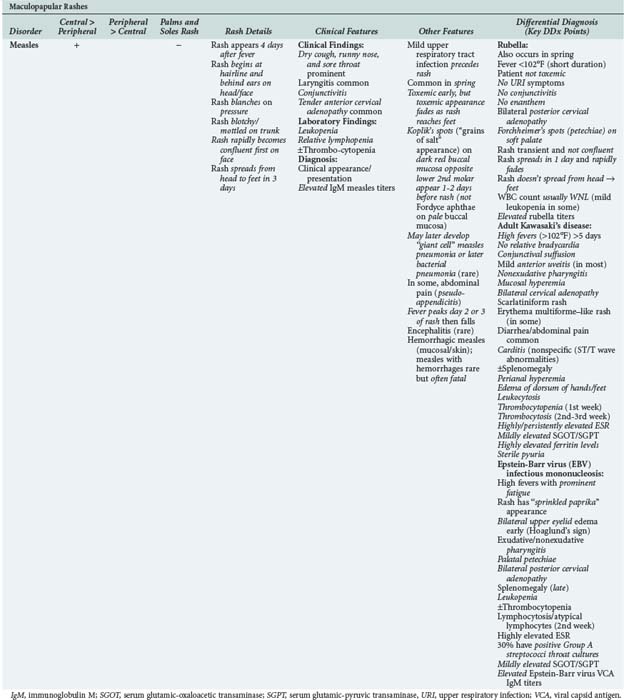

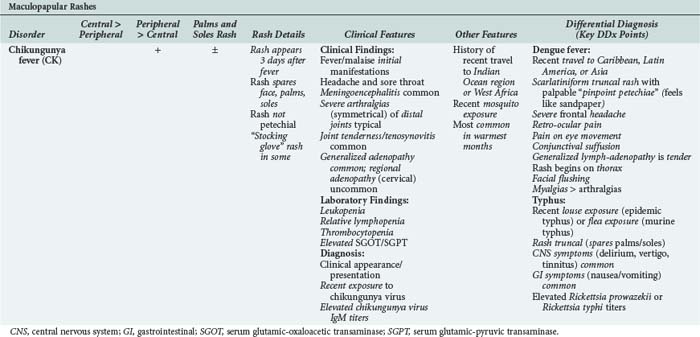

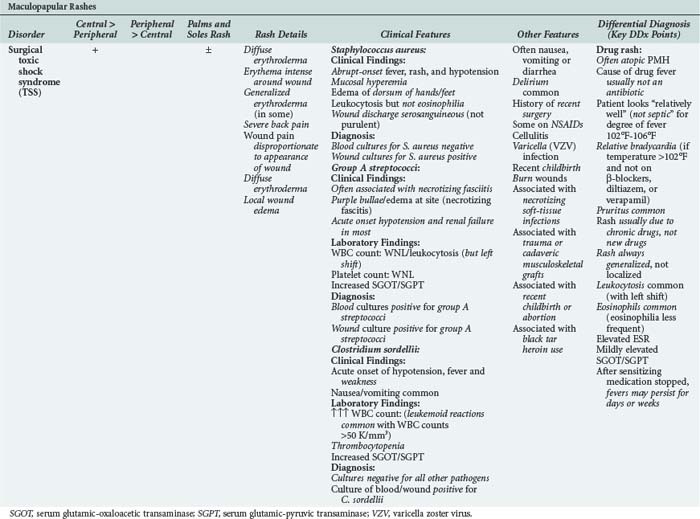

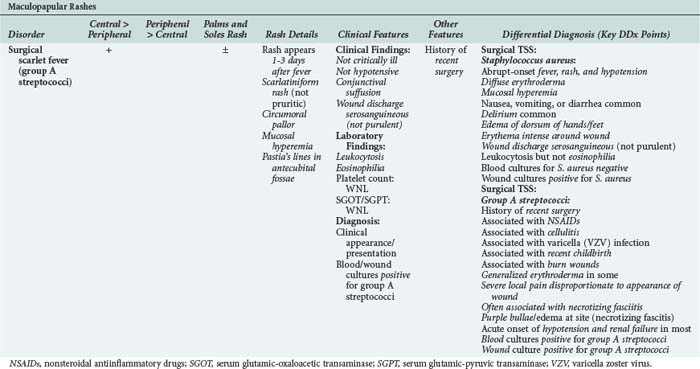

Maculopapular Rashes and Fever

The most common maculopapular rashes/fever associated with serious systemic diseases are toxic shock syndrome (TSS) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE flares can mimic infectious diseases.1,4,11 Thus, SLE pneumonitis can mimic community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), and SLE cerebritis can mimic acute bacterial meningitis (ABM). Laboratory studies can differentiate an SLE flare in the absence of infection from an SLE flare with infection. Typically, SLE flares without infection are accompanied by leukopenia, decreased complement levels, and elevated α1/α2 globulins on serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP).1,8

TSS can occur in any patient colonized/infected with a TSS-1-producing strain of S. aureus. TSS may not come to mind when there are no overt signs of clinical infection (e.g., staphylococcal colonization of the nares). TSS also may be due to group A streptococci or Clostridium sordelli.2,4,11

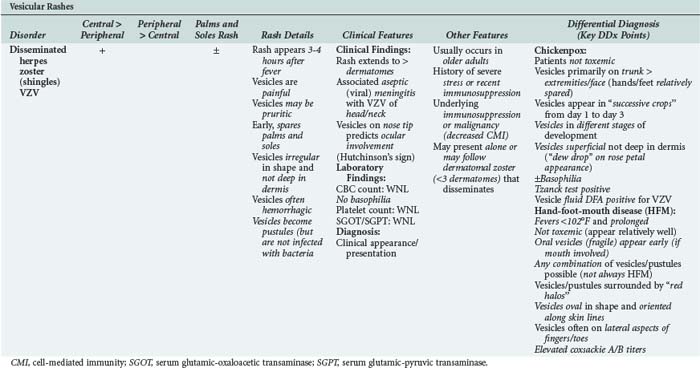

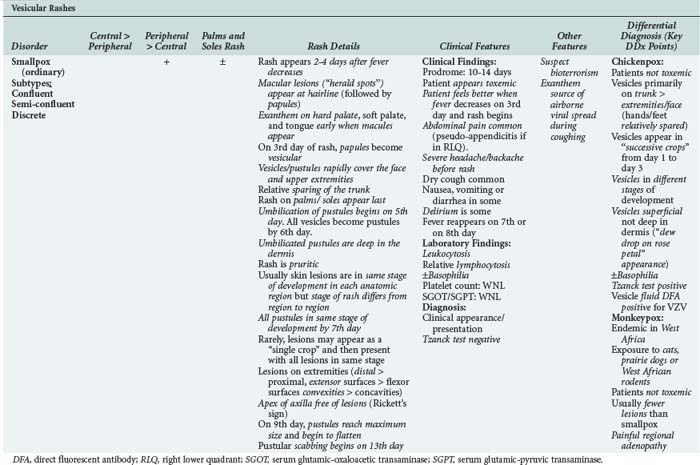

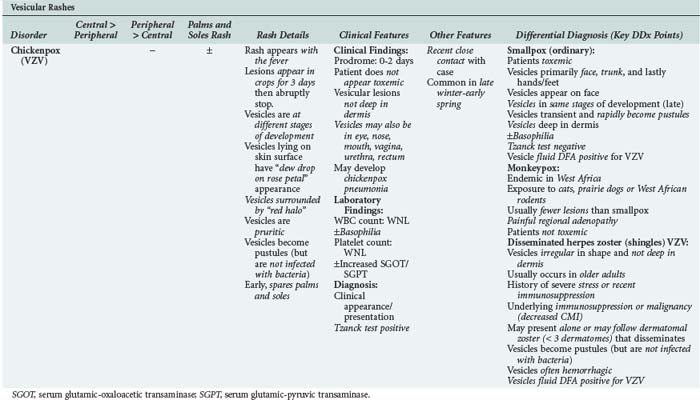

Vesicular/Bullous Rashes and Fever

Vesicular eruptions limit the diagnostic possibilities to chickenpox or herpes zoster (shingles) due to varicella zoster virus (VZV). Herpes zoster may be localized (dermatomal) or disseminated.5–7 Before the appearance of the vesicular rash/fever, dermatomal herpes zoster, depending on dermatomal distribution, can be a difficult diagnostic problem, mimicking many disorders.6 Herpes zoster involving the head and/or neck may be associated with VZV meningitis/encephalitis. Disseminated shingles can resemble chickenpox, but patients with herpes zoster have a prior history of chickenpox.1,4,11

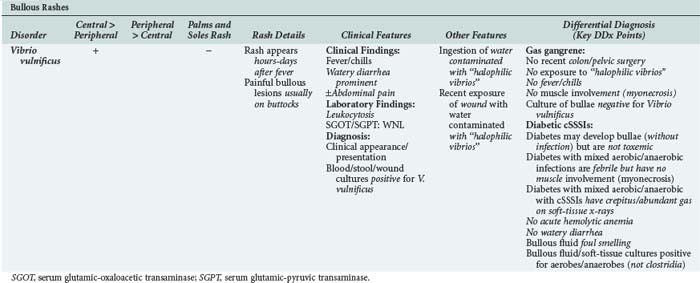

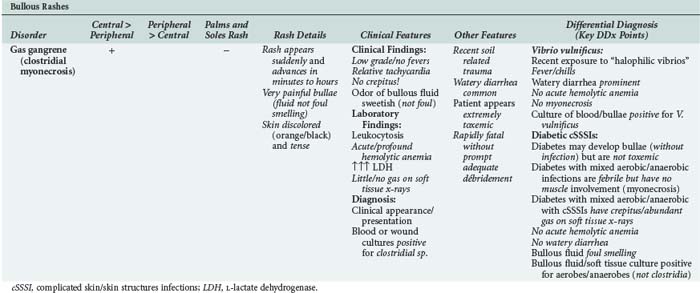

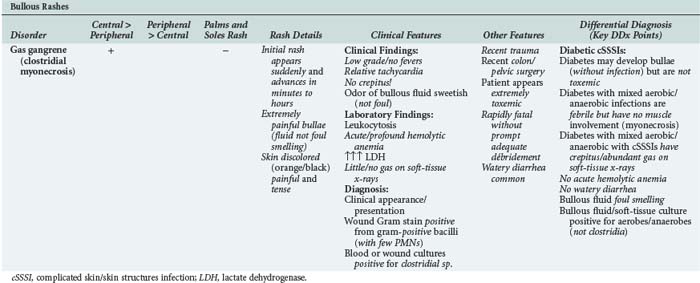

Community-acquired bullous lesions in the ICU may be due to S. aureus soft-tissue infection, Vibrio vulnificus, or gas gangrene (clostridial myonecrosis). Except when due to S. aureus, all the causes of bullae/fever are painful and tense and accompanied by diarrhea. Clostridial myonecrosis, (i.e., gas gangrene) may be present after a crush injury or trauma. The commonest cause of bullae/fever is S. aureus cellulitis/pyoderma.10–12

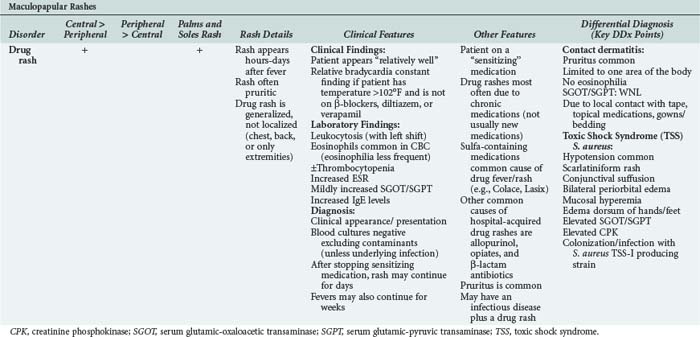

The differential diagnostic features of community-acquired rash/fever are presented in tabular form in Tables 26-1 to 26-16.1–19

Nosocomial-Acquired Rash and Fever

Petechial/Purpuric Rashes and Fever

Staphylococcal bacteremia (high-grade/continuous) is usually related to an intravascular/interventional procedure/device.1,3 Staphylococcal bacteremias or ABE present initially with petechial/purpuric lesions that later can become hemorrhagic and/or gangrenous. The diagnosis is suggested by the peripheral location of the irregular painful petechial/purpuric lesions in the setting of high-grade and/or continuous staphylococcal bacteremia.1,4,11

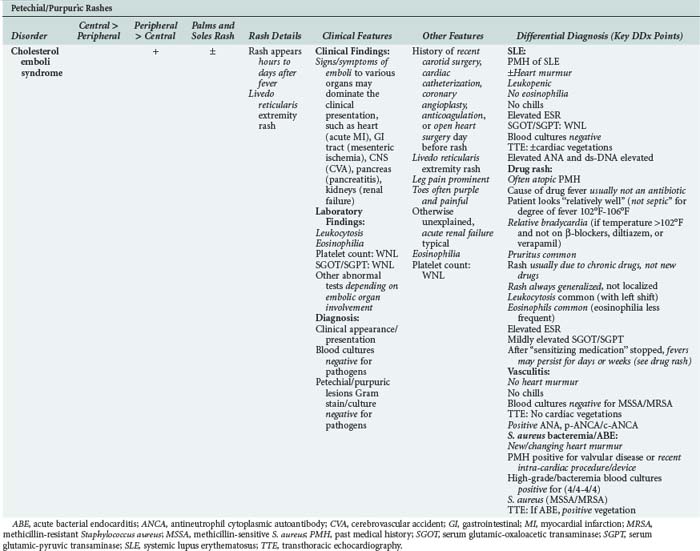

An underrecognized but important cause of nosocomial rash/fever is cholesterol emboli syndrome (CES).20 Cholesterol emboli may be released into the systemic circulation during or following cardiovascular procedures. CES presents as a petechial/purpuric rash with a livedo reticularis–like appearance.1,8 The rash occurs on the trunk and/or extremities and may be accompanied by signs of cholesterol emboli to other organs such as the heart (myocardial infarction), pancreas (acute pancreatitis), kidneys (acute renal failure), or central nervous system (stroke). Excluding drug rash/fever, cholesterol emboli syndrome is the only acute rash in the ICU associated with peripheral eosinophilia.8,20

Drug rashes are drug hypersensitivity reactions with rash/fever. Most patients who develop drug rashes do so after receiving new medications in the hospital, but some develop drug rash/fever years after being on sensitizing chronic medications. Drug rashes are generalized, maculopapular/petechial, and may be pruritic. Fever is usually present and may be high (>102°F); it is regularly accompanied by relative bradycardia.8,9 Mild increases of serum transaminase levels and eosinophiles in the blood smear are common findings.8 The clinical difficulty with drug rash/fever is distinguishing it from underlying medical disorders. Even after discontinuing the sensitizing drug, rash/fever may take days/weeks to resolve.1,3,4,9

Maculopapular Rashes and Fever

Maculopapular rash due to surgical TSS is uncommon. Typical surgical TSS occurs from wound infection several days after surgery. A key clinical clue is that drainage from the wound is serosanguineous rather than purulent.5,7,11,12

Vesicular/Bullous Rashes and Fever

Particularly following distant extremity trauma or distal abdominal surgery, gas gangrene should be considered in the differential diagnosis.3,6 In patients with gas gangrene (i.e., clostridial myonecrosis), the vesicular/bullous eruptions spread rapidly (over minutes/hours). The skin near the bullous lesions is tense and extremely tender, and the fluid in the lesions is not foul smelling. Patients with gas gangrene are afebrile or have only a low-grade fever, but these patients often have watery diarrhea.1,3 A key clinical clue to gas gangrene is rapidly progressive hemolytic anemia due to lysis of red blood cells by clostridial lethicinases.1,4,11 On physical examination, gas in tissues is not clinically detectable or obvious and is not a feature of gas gangrene. On computed tomography (CT) scan, small gas bubbles may be visible along muscle planes.1,3 Large collections of gas in the soft tissues on imaging studies should suggest a mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection by nonclostridial gas-producing organisms. Mixed aerobic-anaerobic soft-tissue infections are most common in diabetics and do not involve muscle (myonecrosis).1,3,10

Fever is usually prominent with mixed aerobic/anaerobic soft-tissue infections, but clostridial gas gangrene characteristically is associated with little or no fever. The differential diagnosis of nosocomial rashes/fever is presented in Tables 26-17 to 26-22.1,4,10,11

The diagnostic approach to rash/fever depends on correctly correlating the location/characteristic of the rash with associated non-dermatologic features such as physical examination findings or laboratory findings, or both, to arrive at a clinical syndromic diagnosis (Tables 26-23 and 26-24).1–20

TABLE 26-23 Differential Diagnostic Clinical Features of Fever and Rash in the ICU

| Infectious Causes | Noninfectious Causes | |

|---|---|---|

| Rash with Shock | TSS MC PSS Overwhelming Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia/ABE Arboviral hemorrhagic fevers Hemorrhagic smallpox Vibrio vulnificus Gas gangrene Dengue fever |

SLE (on steroids) |

| Rash with Mental Changes | RMSF MC (with meningitis) S. aureus ABE (with CNS bleeding) Chikungunya fever Typhus |

SLE |

| Rash with Conjunctival Suffusion | RMSF Dengue fever Arboviral hemorrhagic fevers TSS |

Adult Kawasaki’s disease |

| Rash with Relative Bradycardia | RMSF Typhus Dengue fever Typhoid Arboviral hemorrhagic fevers |

Drug rash |

| Rash with Abdominal Pain | V. vulnificus Gas gangrene Clostridium sordelli Scarlet Fever |

Cholesterol emboli syndrome SLE |

| Rash on Palms and Soles | RMSF TSS Chickenpox Smallpox Monkeypox Scarlet fever |

Drug rash |

| Rash with Diarrhea | V. vulnificus Gas gangrene TSS Dengue fever Arboviral hemorrhagic fevers |

None |

| Rash with Edema of Dorsum of Hands/Feet | RMSF TSS |

Adult Kawasaki’s disease |

| Rash with Bullae | V. vulnificus S. aureus cSSSI Gas gangrene |

None |

| Rash with Heart Murmur | ABE | SLE |

| Rash with Gangrene of Nose Tip | S. aureus ABE | SLE Vasculitis |

| Rash with CVA | Cholesterol emboli syndrome S. aureus ABE |

None |

| Rash with Splenomegaly | RMSF Typhus |

SLE Adult Kawasaki’s disease |

| Rash with Deafness | RMSF Typhus Meningococcal meningitis |

None |

| Rash with Hepato splenomegaly | RMSF Typhus |

Atypical measles |

| Rash with Hepatomegaly | Typhus | None |

ABE, acute bacterial endocarditis; cSSSI, complicated skin/skin structure infection; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DF, dengue fever; MC, meningococcemia; PSS, postsplenectomy sepsis; RMSF, Rocky Mountain spotted fever; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TSS, toxic shock syndrome.

TABLE 26-24 Differential Diagnostic Laboratory Features of Fever and Rash in the ICU

| Infectious Causes | Noninfectious Causes | |

|---|---|---|

| Rash with Elevated SGOT/SGPT | RMSF PSS Arboviral hemorrhagic fevers TSS Dengue fever |

Drug rash Adult Kawasaki’s disease |

| Rash with Relative Lymphopenia | RMSF Chikungunya fever Dengue fever |

SLE Adult Kawasaki’s disease |

| Rash with Leukocytosis | RMSF ABE (Staphylococcus aureus) MC Chikungunya fever |

Drug rash |

| Rash with Eosinophilia | Scarlet fever | Cholesterol emboli syndrome Drug rash |

| Rash with Leukopenia | TSS PSS Dengue fever Smallpox Arboviral hemorrhagic fevers |

SLE Atypical measles |

| Rash with Generalized Adenopathy | Arboviral hemorrhagic fevers Dengue fever Scarlet fever Measles Rubella |

SLE Adult Still’s disease |

ABE, acute bacterial endocarditis; DF, dengue fever; MC, meningococcemia; RMSF, Rocky Mountain spotted fever; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TSS, toxic shock syndrome.

Cunha BA, editor. Infectious diseases in critical care medicine, 3rd ed, New York: Informa, 2010.

Cunha BA. The diagnostic approach to rash and fever in the critical care unit. Crit Care Clin. 1998;8:35-54.

The classic clinical syndromic approach for clinicians for rash and fever encountered in the ICU.

Schlossberg D. Fever and rash. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996;10:101-110.

Classic review on the clinical approach to rash and fever.

Schneiderman PI, Grossman ME, editors. A clinician’s guide to dermatologic differential diagnosis. New York: Informa, 2006.

Lopez FA, Sanders CV. Rash and fever. In: Cunha BA, editor. Educational review manual in infectious disease. 4th ed. New York: Castle Connolly; 2009:15-72.

Cunha CB. Differential diagnosis in infectious diseases. In Cunha BA, editor: Antibiotic essentials, 9th ed, Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett, 2010.

1 Cunha BA, editor. Infectious Diseases in Critical Care Medicine, 3rd ed, New York: Informa, 2010.

2 Cherry JD. Contemporary infectious exanthems. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:199-207.

3 Cunha BA. The diagnostic approach to rash and fever in the critical care unit. Crit Care Clin. 1998;8:35-54.

4 Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious Diseases, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2004.

5 Schlossberg D. Fever and Rash. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996;10:101-110.

6 Schneiderman PI, Grossman ME, editors. A Clinician’s Guide to Dermatologic Differential Diagnosis. New York: Informa, 2006.

7 Lopez FA, Sanders CV. Rash and fever. In: Cunha BA, editor. Educational Review Manual in Infectious Disease. 4th ed. New York: Castle Connolly; 2009:15-72.

8 Cunha CB. Differential Diagnosis in Infectious Diseases. In Cunha BA, editor: Antibiotic Essentials, 9th ed, Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett, 2010.

9 Cunha BA. The clinical significance of fever patterns. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996;10:33-44.

10 Sanders CV. Approach to the diagnosis of the patient with fever and rash. In: Sanders CV, Nesbit LTJr, editors. The Skin and Infection: A Color Atlas and Text. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

11 Schlossberg D, editor. Clinical Infectious Disease. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

12 Shulman JA, Schlossberg D. Handbook for Differential Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases. New York: Appleton Century Crofts; 1980.

13 Cunha BA, editor. Tickborne Infectious Diseases: Diagnosis and Management. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2000.

14 Myers SA, Sexton DJ. Dermatologic manifestations of arthropod-borne diseases. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1994;8:689-712.

15 Palmer SR, Soulsby L, Simpson DIH. Zoonoses. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1998. 1995, p. 296-305

16 Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens, & Practice. vol 1. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999.

17 Cook GC, Zumla A. Manson’s Tropical Diseases, 22nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2009.

18 Strickland GT. Fever in the returned traveler. Med Clin North Am. 1992;76:1375-1392.

19 Wilson ME. A World Guide to Infections. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1991.

20 Lazar J, Marzo KM, Bonoan JT, Cunha BA. Cholesterol emboli syndrome following cardiac catheterization. Heart Lung. 2002;42:452-454.