Chapter 54 Rare Diffuse Interstitial Lung Diseases

Rare Cystic Lung Diseases

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

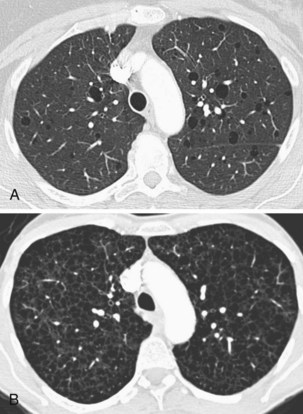

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a cystic lung disease that affects almost exclusively women and has a prevalence of approximately 5 women per 1 million of most populations. LAM may occur sporadically or as part of the autosomal dominant genetic disorder, tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). In both forms the lungs and lymphatics are infiltrated by LAM cells, an abnormal cell clone harboring biallelic inactivating mutations in the genes associated with TSC, either TSC-1 or more often TSC-2. LAM cells accumulate and cause progressive cystic destruction of the lungs, probably by the elaboration of proteolytic enzymes (Figure 54-1). LAM cells form small nodular clumps associated with lymphatic endothelial cells, which in turn form lymphatic channels that allow LAM cells to disseminate throughout the body. LAM cells also infiltrate the axial lymphatics and form the smooth muscle elements of angiomyolipoma, a rare tumor of the perivascular epithelioid cell family, present in up to 40% of women with sporadic LAM and almost all patients with TSC-LAM.

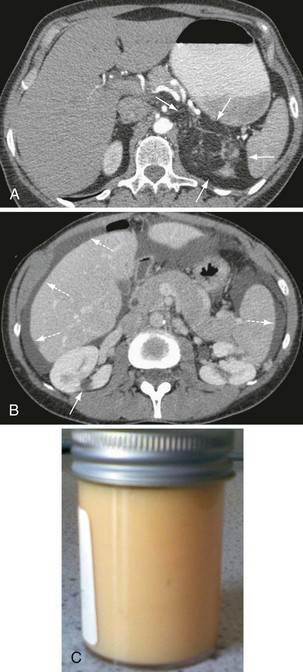

Other, extrapulmonary manifestations are related to lymphatic obstruction and include lymphadenopathy in up to 30% of patients and lymphangioleiomyomas, cystic lymphatic swellings usually in the abdomen, pelvis, or retroperitoneum occurring in up to 20% of patients (Figure 54-2). Thoracic and abdominal chylous collections are present in up to 10% of patients. LAM is also associated with a higher prevalence of meningioma than the general population. Cystic lung destruction results in recurrent pneumothorax and progressive airflow obstruction, with an average decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 120 mL per year (normal, ~27 mL/yr). However, the clinical course of patients with LAM varies, with some remaining stable for many years. At present, no features definitively predict which patients will develop progressive disease; however, onset at a younger age, presentation with breathlessness, and poor lung function at presentation suggest more aggressive disease.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

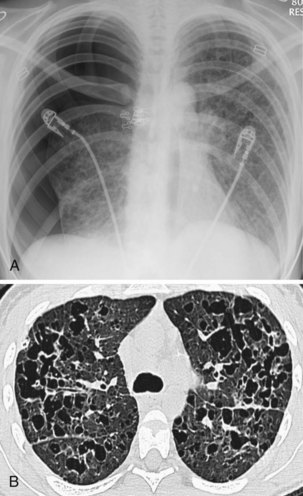

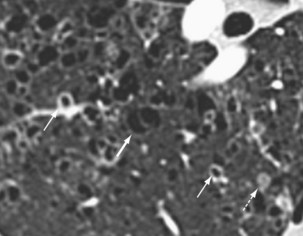

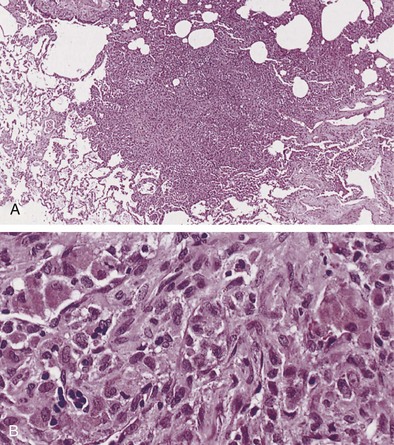

Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically affects individuals between 20 and 40 years of age, almost all of whom are current or recent smokers. The infiltrating Langerhans cell clone expresses the surface protein CD1a and has a characteristic appearance on electron microscopy with Birbeck inclusion granules (Figure 54-3). LCH may coexist with areas of desquamative interstitial pneumonitis, another smoking-related entity characterized by activation of macrophages. Similar to LAM, LCH is of variable severity, with approximately one quarter of LCH patients detected by imaging being asymptomatic. Pneumothorax is the presenting feature in about 20% of patients; the rest present with cough, dyspnea, or weight loss. The chest x-ray film is abnormal in most patients, showing reticular shadowing with midzone and upper-zone predominance (Figure 54-4). The CT scan shows a mixture of nodules, cavitating nodules, and cysts, often with thick, irregular walls forming bizarre shapes (Figure 54-5); characteristically, the bases of the lungs are relatively spared. As the disease progresses, the cysts tend to amalgamate, and nodules become less common. The diagnosis is usually suspected by the combination of these imaging appearances in younger smokers. Absolute confirmation often requires a surgical biopsy (Figure 54-6). However, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid with greater than 5% Langerhans cells identified by CD1a positivity, often with increased macrophages and eosinophils, is supportive and can be diagnostic in the correct clinical context.

Birt-Hogg-DubE syndrome

Birt-Hogg-Dube (BHD) syndrome was first described as the association of fibrofolliculomas, acrocordons, and trichodiscomas; benign skin-colored papules and skin tags of adult onset; presence of lung cysts; and a predisposition to renal cancer. It is now realized that BHD syndrome may be entirely restricted to the lungs, without cutaneous manifestations, and is caused by either germline or somatic mutations in the folliculin (FLCN) gene, a tumor suppressor of unknown function. Patients with pulmonary disease develop lung cysts predominantly in the central and lower zones of the lungs, characteristically around the heart (Figure 54-7). The cysts are 0.2 to 7 cm in size, have thin walls, are often ovoid in shape, and occasionally are multiseptated. The cyst walls have disrupted elastic fibers and are infiltrated by macrophages.

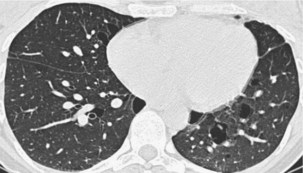

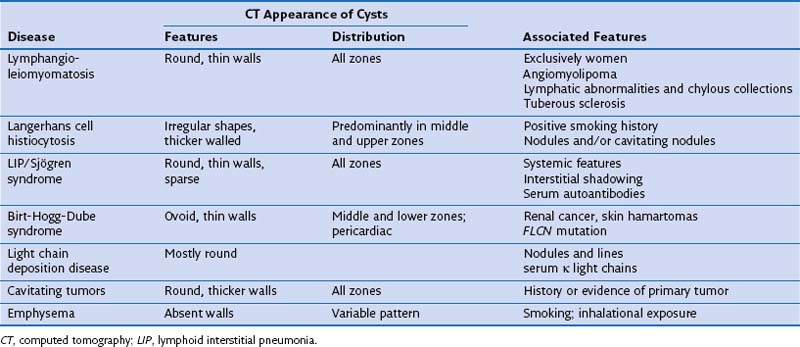

Evaluation of Patients with Cystic Lung Diseases

Diagnosis in patients with cystic lung disease can be difficult. Although imaging and associated features usually suggest the most likely diagnosis, imaging alone is not generally diagnostic (Table 54-1). Suspicion of LAM should be followed by abdominal CT, which will show extrapulmonary manifestations in two thirds of patients; LCH by BAL and CD1a staining, and BHD by FLCN mutation analysis and renal/skin evaluation. Nonspecific or mixed appearances can be evaluated by autoantibody screening, serum κ/λ light chain ratio and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology. Surgical biopsy may be required but can be avoided in many cases. Because many of these diseases have genetic implications for the patient and family, and specific treatments and clinical trials are available, a definitive diagnosis is often necessary.

Other Rare Diffuse Lung Diseases

Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis

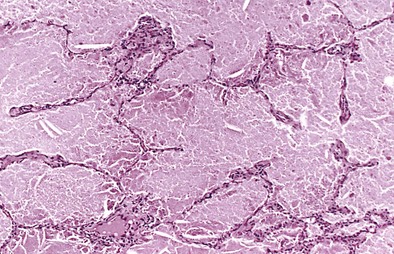

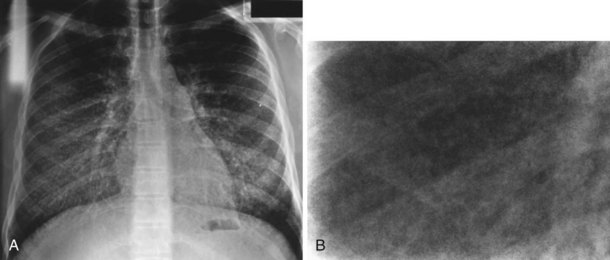

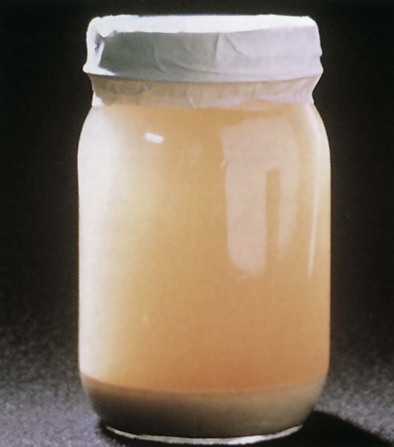

Chest radiography demonstrates consolidation with thickened intralobular septae (Figure 54-8). In a third of cases the changes are asymmetric or unilateral. The pattern is variable and in 50% of PAP patients may be perihilar, resembling the “bat wing” appearance seen in pulmonary edema. The CT appearance of air space shadowing in a geographic pattern with interlobular septal thickening is described as a “crazy paving” pattern (Figure 54-9). This appearance is not specific for PAP and may also be seen in cardiogenic pulmonary edema, bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, alveolar hemorrhage, sarcoidosis, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, nonspecific organizing pneumonia, exogenous lipoid pneumonia, and drug-induced lung diseases. Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of a compatible clinical history and typical radiology and a milky appearance on BAL fluid containing periodic acid–Schiff–positive granular material (Figure 54-10). Open-lung biopsy, although rarely essential, shows accumulation of lipoprotein in the alveolar spaces (Figure 54-11). Nonspecific increase in serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) may also be seen. Lung function is generally restrictive with decreased gas transfer. Anti-GM-CSF antibody titers also show promise as a diagnostic test in both serum and BAL fluid.

Figure 54-10 Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid with classic milky appearance from patient with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis.

Pulmonary Alveolar Microlithiasis

Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of a distinctive calcified micronodular “sandstorm” appearance seen on chest radiography with mid/lower-zone predominance, often obliterating the mediastinal and diaphragmatic contour (Figure 54-12). CT scanning, particularly in advanced disease, demonstrates calcified interlobular septa, pleura, and bronchovascular bundles; perilobular microliths; and often ground-glass attenuation, areas of consolidation, and subpleural cysts. Lung biopsy reveals characteristic lamellar intraalveolar microliths. Mutations in SLC34A2, a gene encoding a sodium-dependent phosphate transporter, highly expressed by alveolar type II cells have been identified in most patients, possibly leading to the aberrant accumulation of calcium phosphate in alveolar spaces.

Pulmonary Manifestations of Rare Systemic Diseases

Allen TC, Chevez-Barrios P, Shetlar DJ, Cagle PT. Pulmonary and ophthalmic involvement with Erdheim-Chester disease: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1428–1431.

Colombat M, Stern M, Groussard O, et al. Pulmonary cystic disorder related to light chain deposition disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:777–780.

Duchateau F, Dechambre S, Coche E. Imaging of pulmonary manifestations in subtype B of Niemann-Pick disease. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:1059–1061.

Eng CM, Germain DP, Banikazemi M, et al. Fabry disease: guidelines for the evaluation and management of multi-organ system involvement. Gent Med. 2006;8:539–548.

Goitein O, Elstein D, Abrahamov A, et al. Lung involvement and enzyme replacement therapy in Gaucher’s disease. QJM. 2001;94:407–415.

Huqun IzumiS, Miyazawa H, et al. Mutations in the SLC34A2 gene are associated with pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:263–268.

Johnson SR. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:1056–1065.

Johnson SR, Cordier JF, Lazor R, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:14–26.

Kamin W. Diagnosis and management of respiratory involvement in Hunter syndrome. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2008;97:57–60.

Lachmann HJ, Hawkins PN. Amyloidosis and the lung. Chronic Respir Dis. 2006;3:203–214.

Pierson DM, Ionescu D, Qing G, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: a case report and review. Respiration. 2006;73:382–395.

Toro JR, Pautler SE, Stewart L, et al. Lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax, and genetic associations in 89 families with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1044–1053.

Trapnell BC, Whitsett JA, Nakata K. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2527–2539.

Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR, et al. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:484–490.