Chapter 2 Rapport

Introduction

The first and most important objective of any client–practitioner interaction is the establishment of client rapport. Aside from facilitating communication between the practitioner and client, good rapport can also improve client assessment and the achievement of expected treatment outcomes.1 Development of this relationship requires time and skill.2 As the therapist’s contribution to rapport is often overlooked in the literature,3 the purpose of this chapter will be to inform readers of the importance of establishing a strong therapeutic relationship with their clients and to provide CAM practitioners with useful strategies to improve client rapport in clinical practice. These skills may also enable practitioners to develop more effective working relationships with other healthcare providers.4 First though, an exploration of the terms used to describe rapport will enable readers to understand the context in which this chapter is situated.

Definitions

Many terms exist that describe the bond between a client and practitioner. The terms most frequently used are ‘therapeutic alliance’, ‘therapeutic relationship’ and ‘client rapport’. By definition, a therapeutic alliance is ‘ a conscious and active collaboration between the patient and therapist’.3 Similarly, a therapeutic relationship is ‘a trusting connection and rapport established between therapist and client through collaboration, communication, therapist empathy and mutual understanding and respect’.4 Rapport is defined as a ‘harmonious relationship’.5 As each of these terms incorporate similar underlying themes, including collaboration, reciprocity, parity and growth, they are considered interchangeable.

The therapeutic alliance and other similar terms are frequently cited in the psychology literature. This may be because the concept of ‘alliance’ is an integral component of many counselling models, such as the ‘here and now’ focused counselling model,6 the lifestyle-oriented nutrition counselling model7 and the four stages of therapy process.8 The latter model suggests that therapist techniques, client involvement in care and the therapeutic alliance are inextricably linked. According to Hill,8 this means that a practitioner is unable to use techniques effectively if a client is not involved in the care and there is no alliance, that a client is not likely to be involved in the care if a therapist does not skilfully use techniques and there is no therapeutic alliance, and that alliance cannot exist without a competent clinician and a participating client. In essence, what this theory suggests is that a competent practitioner who adopts a client-centred, participative and empowering practice style is likely to develop a strong therapeutic alliance. This is a somewhat simplistic interpretation of this relationship, because like other aforementioned models, it does not take into consideration the myriad factors that affect the development of this alliance, as will be elucidated throughout this chapter.

Importance of rapport

There are many reasons why CAM practitioners should be encouraged to develop rapport with their clients. On the whole, building and maintaining rapport leads to positive client outcomes.9–14 A survey exploring the views of 129 Connecticut occupational therapists on therapeutic relationships supports this claim.4 While descriptive surveys are not the most appropriate design for evaluating causal relationships, clinical evidence is beginning to mount that validates the association between good rapport and positive client outcomes.

A cohort study involving 354 patients in a community-based non-profit drug treatment program and 223 patients from a private for-profit program found lower levels of client rapport during counselling treatment resulted in poorer treatment outcomes, including greater cocaine use and criminality.15 Likewise, studies of patients with non-chronic schizophrenia,16 depression,14,17 post-traumatic stress disorder18 and alcoholism19 show that good client rapport improves treatment outcomes.

A reason why well-established rapport may contribute to improved client outcomes may be explained by increased treatment compliance.20 In support of this statement, mothers attending a Los Angeles children’s hospital reported greater treatment compliance when highly satisfied with a physician’s attitude.21 Similarly, perioperative patients who reported a higher level of satisfaction with their care were more likely to take responsibility for their decisions.22

The positive relationship between client satisfaction and treatment compliance has also been reported among patients with chronic pain,23 dermatological disorders24 and diabetes.25 Thus, client satisfaction appears to be a strong motivator of treatment compliance and, as such, maybe fundamental to treatment success. In other words, good rapport may be responsible for improving client satisfaction and treatment compliance,26 and ameliorating client outcomes.

Even though the needs of clients are a priority in any consultation, there are also professional implications associated with building client–practitioner rapport. First, strong therapeutic relationships between clients and clinicians may improve the public’s perception of a practitioner group.4 Second, by increasing client rapport and satisfaction, the risk of litigation might be reduced. Although this claim is speculative, Eastaugh 27 and Panting28 agree that improving client trust and communication, such as that developed through good rapport, results in fewer malpractice claims. Indeed, effective communication could reduce the risk of litigation by increasing rapport and treatment compliance.10,21,29 Alternatively, since good client rapport is critical to formulating adequate diagnoses,21,30 practitioners may misdiagnose less frequently.

Because the practitioner is predominantly responsible for developing and maintaining client rapport,31 the following section will highlight some useful strategies that clinicians can use to strengthen therapeutic relations and improve client outcomes.

Factors that facilitate and constrain client rapport

The clinician’s behaviour and communication style can have significant impact on the practitioner–client relationship. Therapists who are warm, friendly (p = 0.01), affirming and understanding (p = 0.05) demonstrate greater rapport with their clients than those who do not manifest these qualities.32 These attributes may also increase client compliance21 and improve treatment outcomes.33 Another essential ingredient in the development of rapport is time.

Consultation time

Developing client rapport within the first few minutes of a consultation builds client trust34 and minimises defensive attitudes by blurring the transition from small talk to formal assessment.21,35 Constraints on practitioner time, such as escalating workloads, costs, and organisational and political pressures diminish the opportunity for practitioners to build a strong rapport with their clients.4,36

Evidence from a recent survey of 186 outpatients attending a Japanese psychiatric clinic lends support to the postulated relationship between consultation time and rapport. The study found session concentration (or session duration divided by session frequency) to be positively correlated with patient satisfaction of physician communication style (p<0.05). Higher levels of patient satisfaction also predicted lower levels of depression and anxiety. The authors concluded that communication satisfaction, which was predicted by consultation duration and frequency, was indicative of a good therapeutic relationship.37 The correlation between increased consultation duration and improved physician communication is consistent with findings from an earlier study of general practitioners.38

Because time constraints are likely to have a negative impact on client outcomes,4 adequate consultation time is as important as effective communication skills. Thus, practitioners of professions that necessitate longer consultations, such as CAM, may have the capacity to establish greater rapport with their clients than practitioners constrained by time. For clinicians whose time is scarce, strategies such as providing a quiet environment, actively listening, avoiding interruptions and displaying non-hurried actions31 may portray to the client that the practitioner has time to listen, which may in turn facilitate greater disclosure of client concerns. Even though these strategies may assist in developing rapport between practitioner and adult clients, children may require a more distinctive approach.

In a study of 64 3.5-year-old children, the effects of practitioner–child interaction on the establishment of rapport were investigated.39 Children left alone in a playroom remained with a stranger longer when the stranger greeted the child quickly but interacted with the child for a greater period of time. Conversely, children who were approached gradually but only interacted with the individual for a brief period of time were also less likely to leave the playroom. Unlike adults, too much time spent trying to establish rapport with a child may inversely affect the establishment of this relationship.

Consultation style

A collaborative consultation style is also essential to building rapport.3,20 Such an approach may empower the individual to participate in their own care and enable the client to grow.5,40 Clinicians adopting a technical or parental role as opposed to a collaborative role may compromise client rapport, respect, compliance and treatment outcomes by invoking negative client attitudes.36 Hence, a relationship in which the practitioner takes control and in which the client follows orders is neither conducive to client growth nor the development of good rapport.

The delivery of a collaborative consultation style requires CAM practitioners to adopt a client-centred approach, develop mutually agreed upon goals with the client41 and involve the client’s family and/or significant others in the consultation.4 A critical first step to achieving these outcomes is understanding how a clinician’s interview style can impede or foster collaborative consultation, particularly a practitioner’s phrasing of questions and statements. This is exemplified in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Questions or phrases that hinder or facilitate client–practitioner collaboration

| Hindering (paternal) phrases | Facilitating (collaborative) phrases |

|---|---|

| What can I do for you? | What are your concerns? |

| How can I help you? | What brought you here today? |

| What you should concentrate on is … | What condition concerns/affects you the most? |

| What you need to do is … | What we could do is … |

| I am going to prescribe for you … you will need to… | These are the different treatment approaches we could take … do you have any thoughts or preferences about these? |

| I do not want you to …I want you to … | If we could work together on reducing or increasing … this may help us to … |

By adopting a collaborative approach, practitioners also ensure that a client’s right to make decisions about the choice of treatment is retained and respected. This, together with informed consent, is not only crucial to the delivery of ethical care, but is also conducive to establishing good client–practitioner rapport. Equally important is the need for effective communication.

Communication skills

CAM practitioners choosing to develop good rapport with their clients will need to possess skills that facilitate effective communication. Skills such as listening and responding are fundamental to the exchange of information, as are open questioning, reflecting, paraphrasing and summarising.41 Effective communication and optimal client–practitioner interaction also require the clinician to identify and respect individual differences in gender, developmental stages, cognitive ability, values, beliefs, priorities, culture, social circumstance and health literacy.4,34 The latter is particularly pertinent, as physician explanations of conditions and processes of care are often in language that is too technical or in other ways not tailored to the individual with poor health literacy,42 which can result in a lack of understanding and, consequently, poor treatment compliance. Thus, it is important that CAM practitioners adapt their language to the needs of the client, and to ensure that they do not speak in language that is too technical for people with poor health literacy. Likewise, practitioners should avoid oversimplifying information for people with good health literacy, such as health professionals and people well versed in their disease, as this could be perceived as condescending and may act as a potential barrier to the establishment of rapport. Other strategies that foster communication between clinician and client are listed in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2 Practitioner strategies and behaviours that improve client trust, communication and rapport

| Maintain | an open posture attentiveness a collaborative relationship client comfort confidentiality and trust enthusiasm eye contact interest in client concerns objectivity. |

| Avoid | an authoritarian demeanour interruptions jargon and technical language passing judgement. |

| Be | altruistic confident dependable empathetic empowering engaging and interactive flexible friendly genuine honest open minded reassuring and supportive respectful of client wishes and needs sensitive sincere warm. |

| Use | open-ended questions rationales for procedures, treatments and decisions. |

Effective communication is particularly reliant on the establishment of client trust. It is through trust and respect that a practitioner can enhance communication and facilitate the development of rapport.40,43 However, client trust is not a skill that can be acquired, but an attribute that must be developed. Practitioners who are clinically competent, consistent, honest and committed to the client44 may accelerate the development of this trust and, in turn, improve client communication, rapport and clinical outcomes.

Awareness of the signs of increasing or worsening rapport may enable practitioners to better evaluate the strength of this relationship. Signs of growing rapport may be manifested in an increased flow of conversation, the disclosure of sensitive information, relaxed body language, increased eye contact, and improvements in listening and responding. Poor client rapport may present as long periods of silence, sudden withdrawal of conversation,45 lack of eye contact, brief responses and defensive body language.

Clinical environment

Music therapy, for instance, has been shown, albeit modestly, to reduce pain intensity levels,46 elevate mood47 and reduce anxiety.48 Exposure to music therapy has also been reported by most patients receiving postanaesthesia care to be a pleasant to very pleasant experience, with a favourable attitude towards music therapy being positively correlated with the degree of relaxation and satisfaction (p<0.05). Despite insufficient data on the effect of music therapy on patients within non-hospital environments being available, it is likely that exposure to music within the clinical setting will improve client comfort, mood and satisfaction to some degree, and thus hasten the development of client rapport. The provision of ambient music in clinic waiting areas, in conjunction with other noise control measures such as soundproofing of walls and doors, may also help to preserve client confidentiality and privacy. Therefore, whether it is for ethical, legal or clinical reasons, there appears to be some merit in adopting this approach.

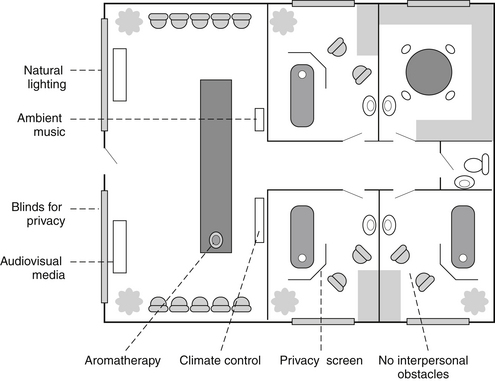

Other measures that may improve client satisfaction and mood and thus help to foster rapport include shortened waiting times (p = 0.005), increased exposure to educational interventions (p<0.001),49 and aromatherapy, particularly the presence of diffused orange essential oil in the waiting room.50 Ambient room temperature is another important consideration; undesirable room temperature may adversely affect client comfort, exacerbate specific symptoms and/or affect the accuracy of clinical assessments, such as capillary perfusion.51 An example of a clinical environment that fosters client–practitioner rapport is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

In cases where rapport fails to develop, practitioners may need to critically reflect on their techniques, the environment and the client to isolate the factors that impede the growth of client rapport. The CAM practitioner may also choose to utilise the strategies listed in Table 2.2 to facilitate the development of this relationship.1–5,10,20,26,30,34,41,43,52

Summary

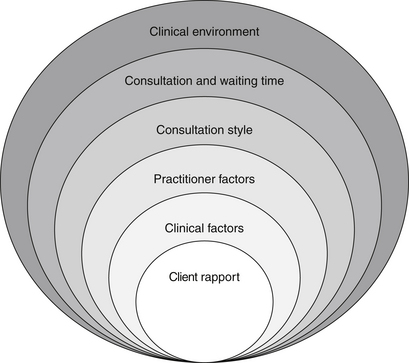

The development of client–practitioner rapport and the subsequent production of positive client outcomes are dependent on trust, effective communication skills, the clinical environment, practitioner behaviour, consultation style and time. As illustrated in Figure 2.2, these elements can be conceptualised as layers, ranging from intrinsic client-related factors, to more extrinsic environmental factors. By adopting the techniques identified in this chapter, practitioners may significantly improve client health and wellbeing, as well as the efficiency of CAM services. Rapport has widespread implications for the client, the practitioner, the community and the healthcare system, although further research is still needed to evaluate the effect rapport has on the outcomes of CAM interventions. While the initial stages of the clinical consultation are critical to building client rapport, the development of this relationship continues throughout the entire consultation process, particularly during the second stage of DeFCAM – the clinical assessment.

Learning activities

1. DeLaune S.C., Ladner P.K. Fundamentals of nursing: standards and practice, 3rd ed. Albany: Delmar Cengage Learning; 2006.

2. Kennedy M. In doc we trust: building rapport with young patients takes time and skill. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2000;99(2):33-36.

3. Ackerman S.J., Hilsenroth M.J. A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(1):1-33.

4. Cole M.B., McLean V. Therapeutic relationships re-defined. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2003;19(2):33-56.

5. Spink L.M. Six steps to patient rapport. AD Nurse. 1987;2(2):21-23.

6. Weaver J. ‘Here and now’ focussed counselling: a model for nurses. Contemporary Nurse. 2002;13(2–3):239-248.

7. Horacek T.M., Salomon J.E., Nelsen E.K. Evaluation of dietetic students’ and interns’ application of a lifestyle-oriented nutrition-counseling model. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;68:113-120.

8. Hill C. Therapist techniques, client involvement, and the therapeutic relationship: inextricably intertwined in the therapy process. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice. Training. 2005;42(4):431-442.

9. Martin D.J., Garske J.P., Davis M.K. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):438-450.

10. Mejo S.L. Communication as it affects the therapeutic alliance. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 1989;1(1):20-22.

11. Karver M.S., et al. Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: The evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:50-65.

12. Paley G., Lawton D. Evidence-based practice: accounting for the importance of the therapeutic relationship in the UK National Health Service therapy provision. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2001;1(1):12-17.

13. Shirk S.R., Karver M. Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):452-464.

14. Zuroff D.C., Blatt S.J. The therapeutic relationship in the brief treatment of depression: contributions to clinical improvement and enhanced adaptive capacities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(1):130-140.

15. Joe G.W., et al. Relationships between counselling rapport and drug abuse treatment outcomes. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(9):1223-1229.

16. Frank A.F., Gunderson J.G. The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia. Relationship to course and outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47(3):228-236.

17. Krupnick J.L., et al. The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: findings in the national institute of mental health treatment of depression collaborative research program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(3):532-539.

18. Cloitre M., Stovall-McClough K.C., Chemtob C.M. Therapeutic alliance, negative mood regulation, and treatment outcome in child abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):411-416.

19. Connors G.J., et al. The therapeutic alliance and its relationship to alcoholism treatment participation and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(4):588-598.

20. Crellin K. Communication briefs. Nursing Management. 1999;30(1):49.

21. Jarratt L., Nord W. Establishing patient rapport and communication. South Dakota Journal of Medicine. 1985;38(1):19-23.

22. Larsson U.S., et al. Patient involvement in decision-making in surgical and orthopaedic practice: effects of outcome of operation and care process on patients’ perception of their involvement in the decision-making process. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 1992;6(2):87-96.

23. Hirsch A.T., et al. Patient satisfaction with treatment for chronic pain: predictors and relationship to compliance. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2005;21(4):302-310.

24. Renzi C., et al. Association of dissatisfaction with care and psychiatric morbidity with poor treatment compliance. Archives of Dermatology. 2002;138(3):337-342.

25. Alazri M.H., Neal R.D. The association between satisfaction with services provided in primary care and outcomes in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 2003;20(6):486-490.

26. O’Connor G.T., Gaylor M.S., Nelson E.C. Health counselling: building patient rapport. Physician Assistant. 1985;9(3):154-155.

27. Eastaugh S.R. Reducing litigation costs through better patient communication. The Physician Executive. 2004;30(3):36-38.

28. Panting G. How to avoid being sued in clinical practice. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2004;80(941):165-168.

29. Davis C.M. Patient practitioner interaction: An experiential manual for developing the art of health care, 4th ed. Thorofare: SLACK Incorporated; 2006.

30. Franke J. Communication tune-up: forty tips to improve rapport with your patients. Texas Medicine. 1996;92(3):36-42.

31. Purtilo R., Haddad A. Health professional and patient interaction, 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

32. Najavits L.M., Strupp H.H. Differences in the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapists: a process-outcome study. Psychotherapy. 1994;31(1):114-123.

33. Williams D.D.R., Garner J. The case against ‘the evidence’: a different perspective on evidence-based medicine. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:8-12.

34. Harkreader H., Hogan M.A., Thobaben M. Fundamentals of nursing: caring and clinical judgement, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2007.

35. Gumenick N.R. Classical five-element acupuncture. Acupuncture Today. 4(2), 2003.

36. Crepeau E.B., Cohn E.S., Schell B.A.B. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

37. Igarashi H., et al. Consultation frequency and perceived consultation time in a Japanese psychiatric clinic: their relationship with patient consultation satisfaction and depression and anxiety. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2008;62(2):129-134.

38. Roland M.O., et al. The ‘five minute’ consultation: effect of time constraint on verbal communication. British Medical Journal. 1986;292(6524):874-876.

39. Donate-Bartfield E., Passman R.H. Establishing rapport with preschool-age children: implications for practitioners. Children’s Health Care. 2000;29(3):179-188.

40. Fox V. Therapeutic alliance. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2002;26(2):203-204.

41. MacDonald P. Developing a therapeutic relationship. Practice Nurse. 2003;26(6):56-59.

42. Schillinger D., et al. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2004;52:315-323.

43. Myers D.G. Psychology, 8th ed. New York: Worth Publishers; 2006.

44. Usherwood T. Understanding the consultation: evidence, theory and practice. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1999.

45. Latey P. Placebo: a study of persuasion and rapport. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2000;4(2):123-136.

46. Cepeda M.S., et al. Music for pain relief. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, issue. 2, 2006.

47. Maratos A.S., et al. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, issue. 1, 2008.

48. Evans D. Music as an intervention for hospital patients: a systematic review. Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Nursing and Midwifery. 2001:1-58.

49. Oermann M.H. Effects of educational intervention in waiting room on patient satisfaction. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2003;26(2):150-158.

50. Lehrner J., et al. Ambient odor of orange in a dental office reduces anxiety and improves mood in female patients. Physiology and Behaviour. 2000;71(1–2):83-86.

51. Gorelick M.H., Shaw K.N., Baker M.D. Effect of ambient temperature on capillary refill in healthy children. Pediatrics. 1993;92(5):699-702.

52. Ramjan L.M. Nurses and the ‘therapeutic relationship’: caring for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;45(5):495-503.