Radical Prostatectomy

Introduction

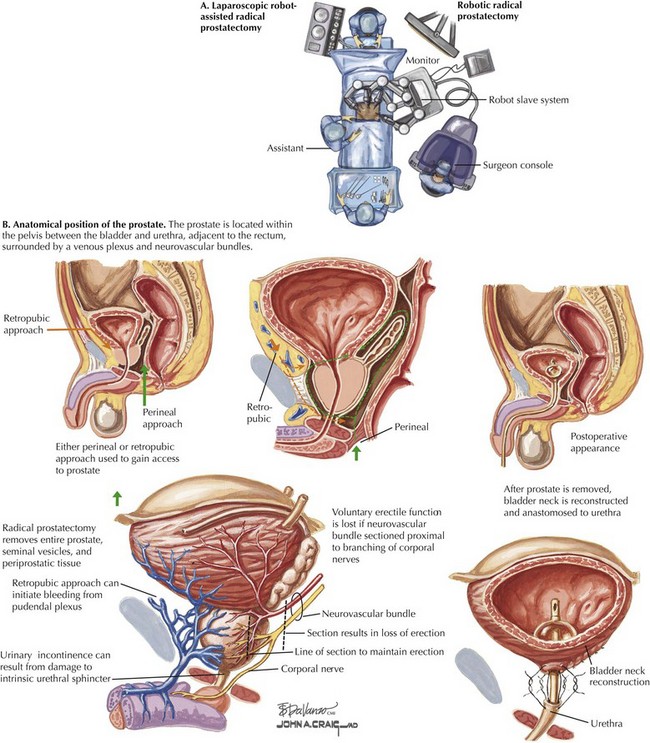

Traditionally, radical prostatectomy has been performed in the open retropubic or perineal approach. In the last decade, however, use of minimally invasive approaches has dramatically increased, particularly laparoscopic robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (Fig. 54-1, A). This approach has gained popularity because of its greater technical ease for the surgeon, especially with laparoscopic suturing, which allows for more precise suture placement during the vesicourethral anastomosis.

Prostate Cancer: Therapeutic Principles

The variation in prostate size and shape, as well as its location deep in the pelvis between the bladder and urethra and adjacent to the rectum, make surgical extirpation challenging (Fig. 54-1, B). Additionally, the prostate is surrounded by a venous plexus, and the neurovascular bundles responsible for erection run alongside the prostate. Therefore the surgical dissection required during radical prostatectomy should be performed meticulously by a surgeon with detailed knowledge of the anatomic relationships of the prostate.

Surgical Approach

Posterior Prostatic Dissection

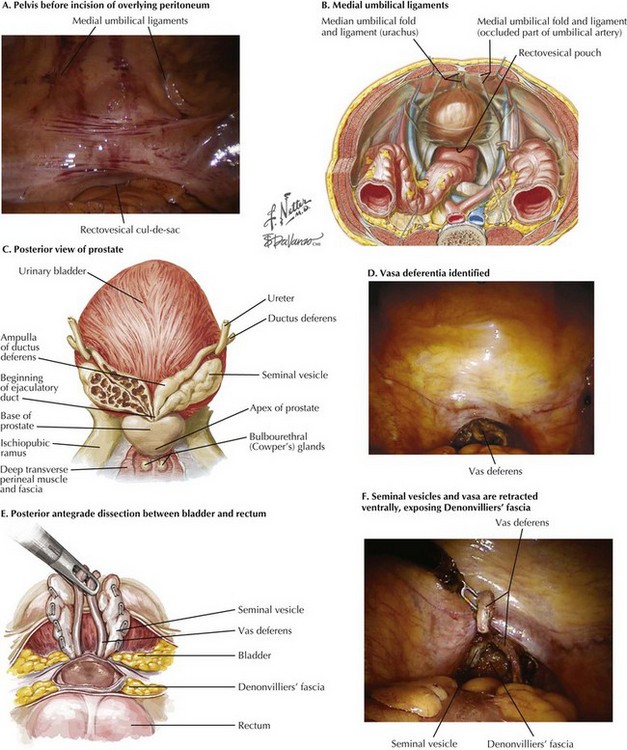

Initial inspection of the pelvis is performed to identify the relevant landmarks: the medial umbilical ligaments and the vasa deferentia. The rectovesical cul-de-sac (pouch of Douglas) is approached, and the courses of the vasa are identified through the peritoneal layer (Fig. 54-2, A-D).

The seminal vesicles and vasa are retracted ventrally, exposing Denonvilliers’ fascia (Fig. 54-2, E and F). This fascia is incised sharply just dorsal to the base of the prostate. This approach allows entry into a plane containing perirectal fat, and the surgeon can then carefully dissect the prostate off of the rectum in an antegrade direction to the prostatic apex.

Development of Space of Retzius

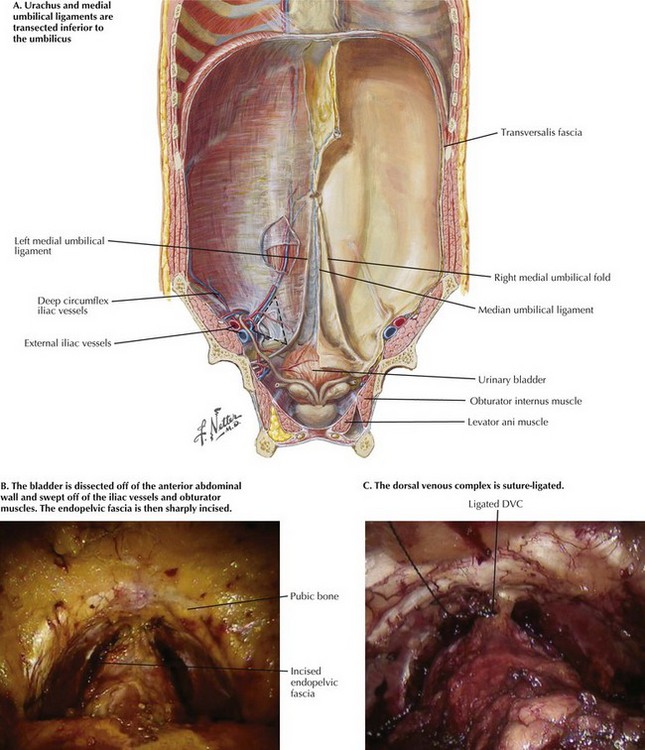

The urachus and medial umbilical ligaments are transected with electrocautery just inferior to the umbilicus (Fig. 54-3). The bladder is carefully dissected off of the anterior abdominal wall just deep to the posterior rectus sheath and transversalis fascia. The lateral limits of the dissection are the lateral borders of the medial umbilical ligaments.

Bladder Neck Dissection

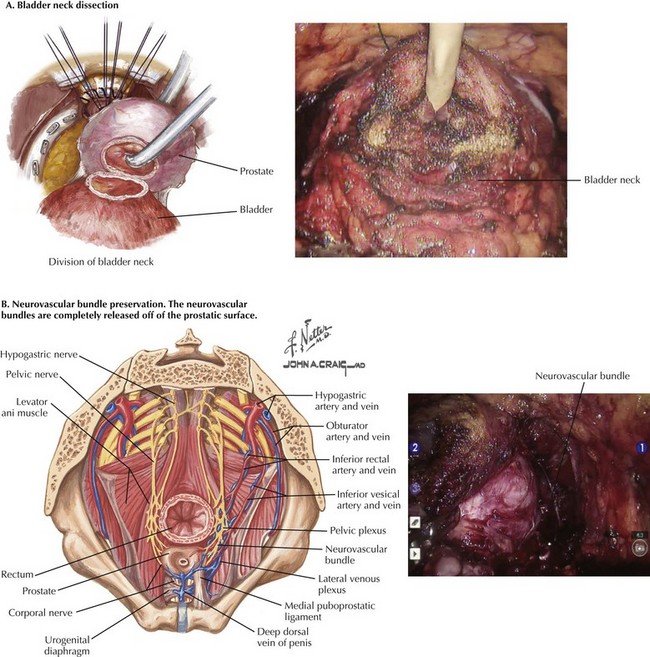

The contour of the prostate, the pliability of the tissues, and the balloon from the urethral catheter are used to identify the bladder neck just proximal to the base of the prostate. Electrocautery is then used to dissect the anterior, lateral, then posterior bladder neck off of the base of the prostate (Fig. 54-4, A).

Neurovascular Bundle Preservation

Release of the neurovascular bundles can be performed at this point in the procedure, or after control of the vascular pedicles to the prostate (Fig. 54-4, B). The levator fascia is sharply incised over the anterolateral prostate, preserving the underlying prostatic fascia. This incision is carried distal beyond the prostatic apex, and proximal to the vascular pedicles.

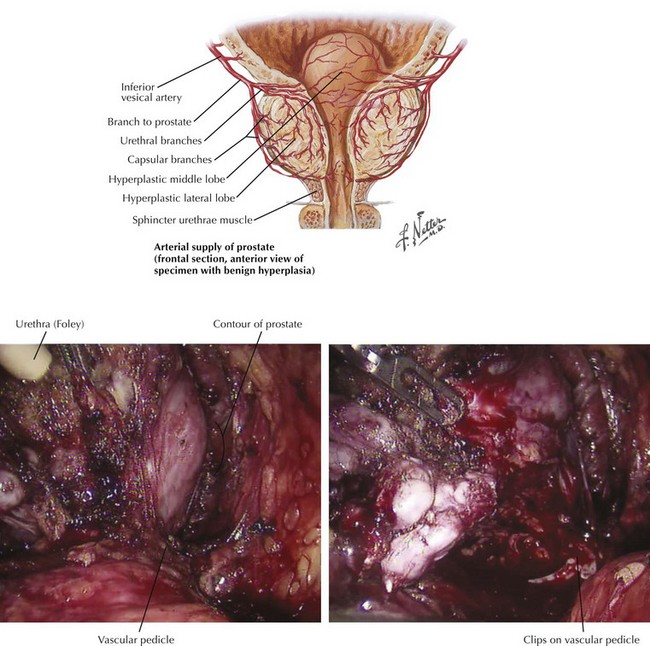

Prostatic Pedicle Ligation and Division of Deep Dorsal Venous Plexus

The base of the prostate is left attached by the vascular pedicles (Fig. 54-5). The seminal vesicles and vasa are retracted anteriorly and contralaterally, defining the prostatic pedicles at the 5 and 7 o’clock positions. The pedicles are then clipped or suture-ligated and transected sharply.

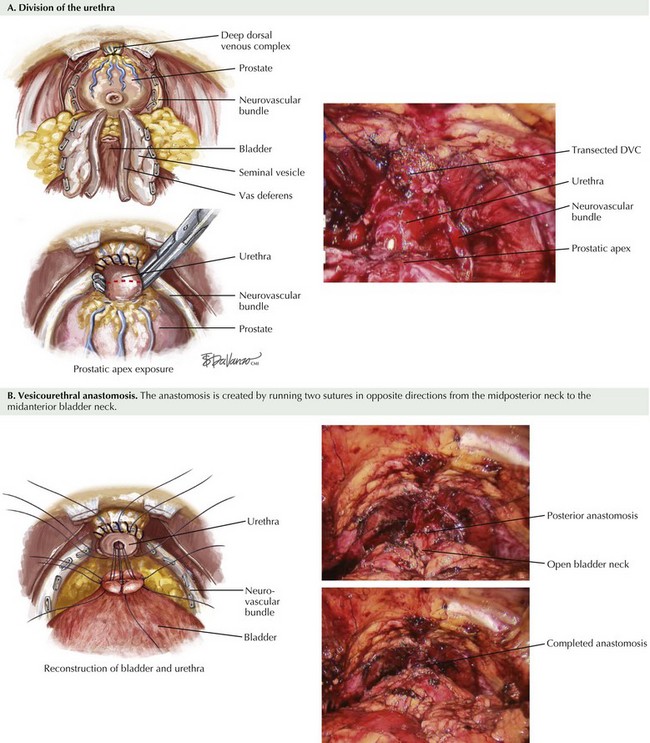

Division of Urethra

The apex of the prostate is further defined with careful dissection around the urethra (Fig. 54-6, A). Inspection is done to confirm the neurovascular bundles are dissected off of the prostatic apex to ensure that the bundles will not be inadvertently transected during urethral division. The anterior urethra is then divided sharply just distal to the prostate apex.

Vesicourethral Anastomosis

The vesicourethral anastomosis is created by running two sutures in opposite directions from the midposterior to the midanterior bladder neck (Fig. 54-6, B). Adequate apposition of the posterior bladder neck is needed to avoid postoperative urine leaks, because this is the area of greatest tension.

Bill-Axelson, A, Holmberg, L, Ruutu, M, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1708.

Ficarra, V, Novara, G, Artibani, W, et al. Retropubic, laparoscopic, and robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and cumulative analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1037.

Hu, JC, Gu, X, Lipsitz, SR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive vs open radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2009;302:1557.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. www.nccn.org, 2010.

Young, HH. The early diagnosis and radical sure of carcinoma of the prostate. Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull. 1905;16:315.