Radical Hysterectomy

Supplemental Anatomy for Radical Hysterectomy and Pelvic Lymphadenectomy

An understanding of the anatomy of the retroperitoneal space is required to initiate lymphadenectomy and exposure of the great vessels (Fig. 12–1A–C). Although the course of the ureter was covered earlier in this section, additional anatomic dissection views are needed to help the reader understand the operative steps necessary to perform radical hysterectomy (Fig. 12–2). In truth, radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy are exercises in anatomic dissection. It is therefore imperative to have precise knowledge of the retroperitoneum, particularly the relationships of the ureter to the great vessels and of the vessels to one another (Fig. 12–3A–L).

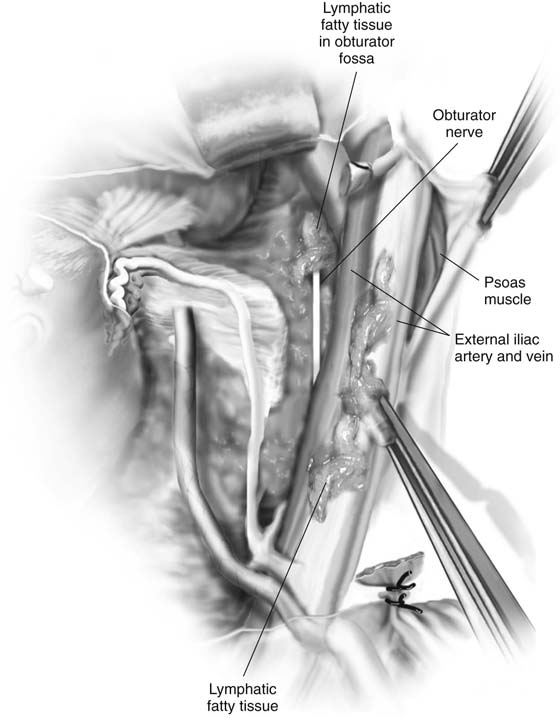

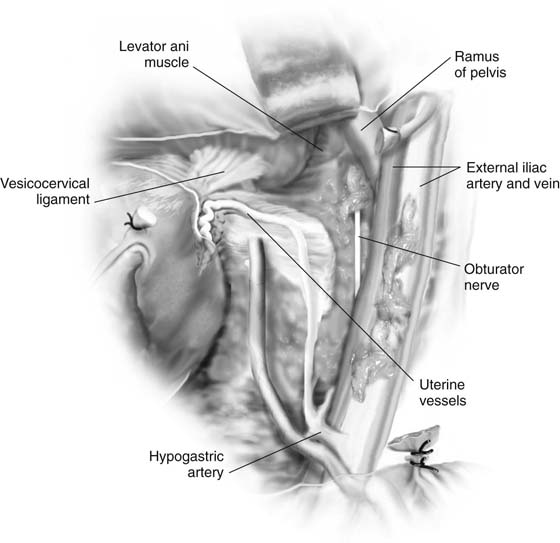

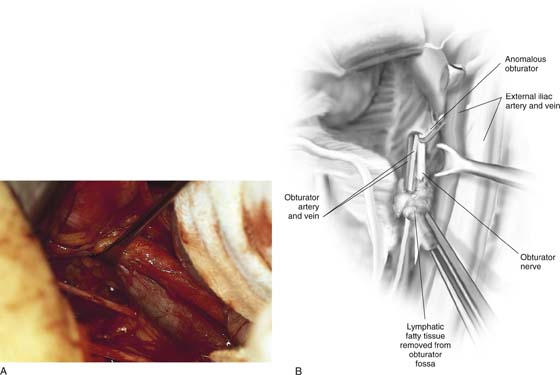

The structures most vulnerable to injury and most difficult to repair are the veins accompanying the large pelvic arteries (Fig. 12–4). The precise location of these veins and their careful retraction are crucial to the safe performance of the surgery (Fig. 12–5A, B). All of these anatomic relationships come together during the dissection of the obturator fossa (Fig. 12–6).

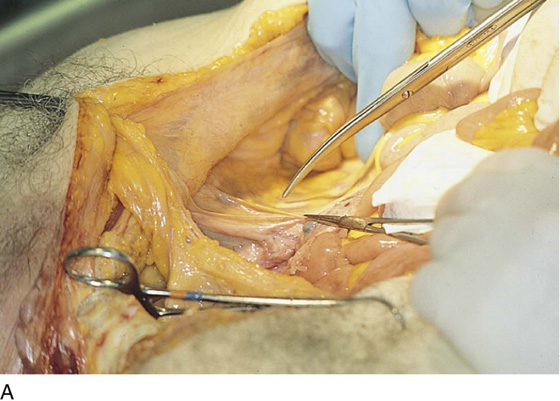

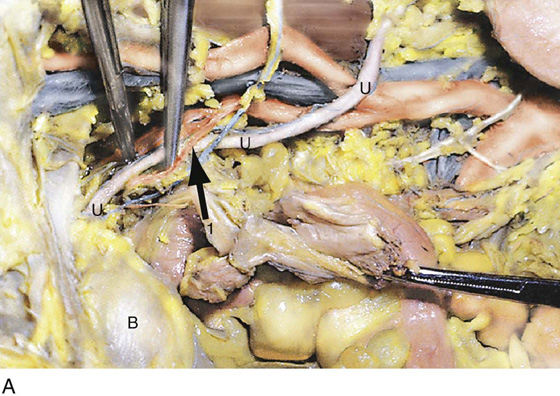

FIGURE 12–1 A. The retroperitoneum is entered by grasping the round ligament and cutting the peritoneum at the top of the broad ligament in a linear and foot-to-head direction. B. The scissors point to the belly of the psoas major muscle, which is lateral to the external iliac artery. C. The external iliac artery has now been exposed and lies above the spread tips of the scissors.

FIGURE 12–2 Orientation view of the uterus in situ with a ligature placed into the fundus for traction.

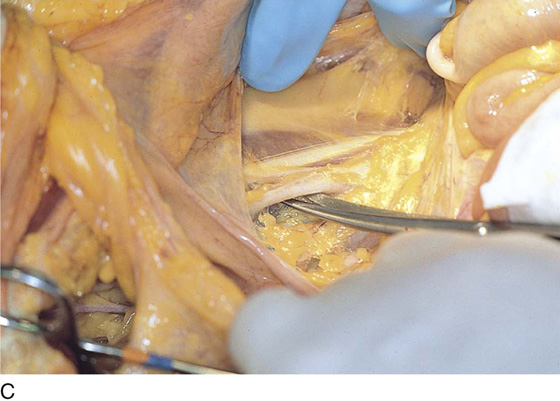

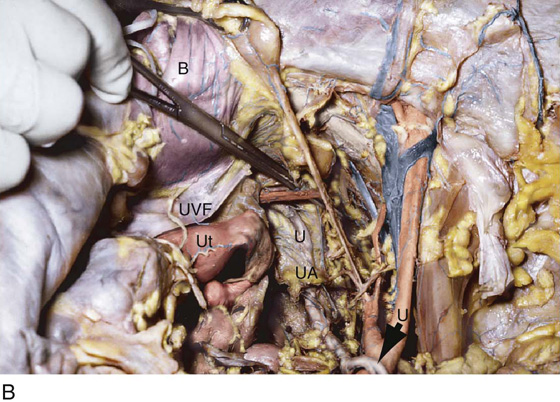

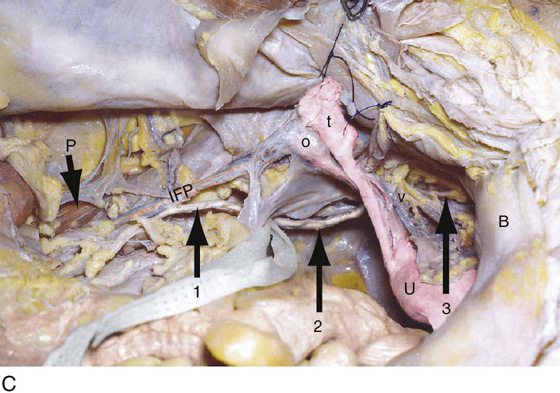

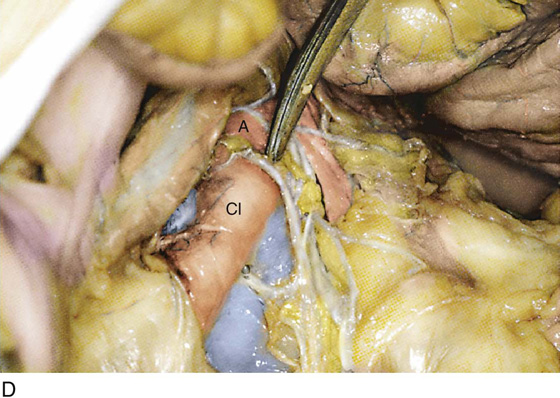

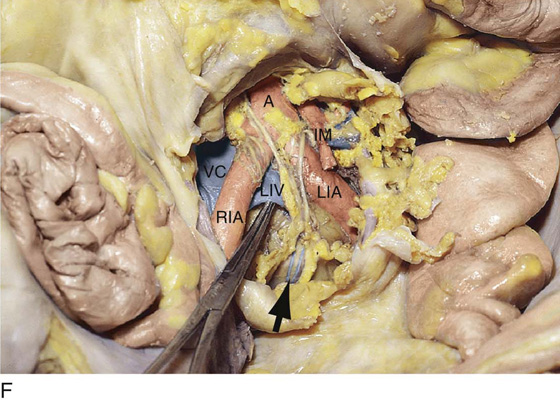

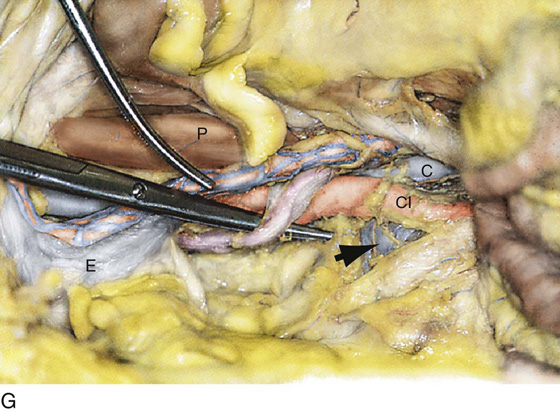

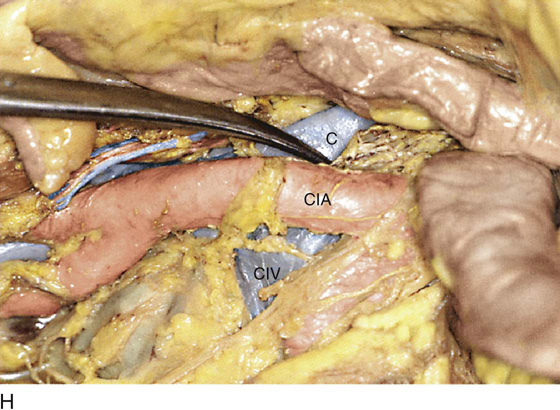

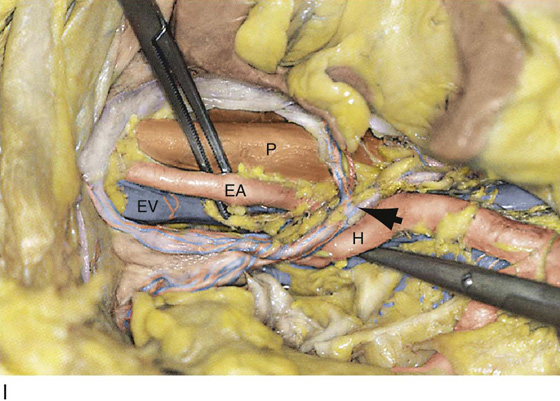

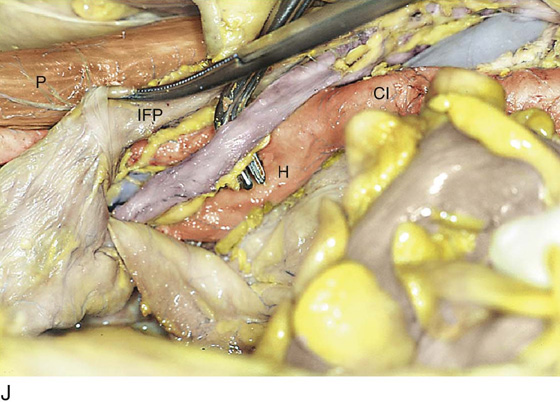

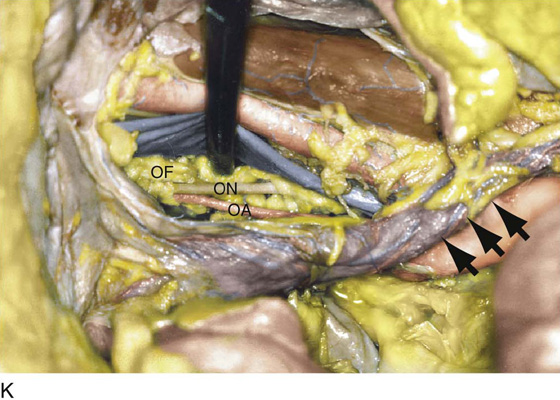

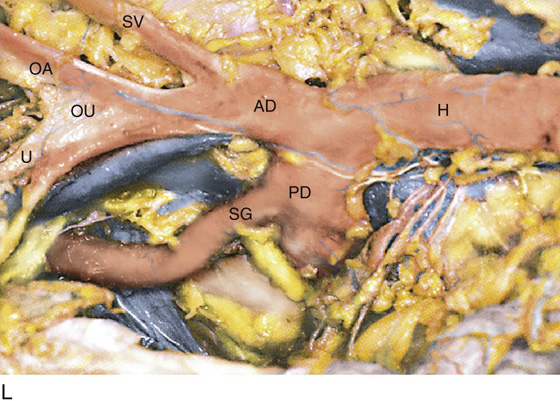

FIGURE 12–3 A. The entire course of the right ureter is shown here. U, ureter; 1, uterine artery; B, bladder (view from left side). B. The entire course of the right ureter viewed from overhead. Ut, uterus; U, ureter; B, bladder; UVF, uterovesical fold; UA, feeding vessel to ureter. The clamp points to the uterine artery. C. The entire course of the left ureter is shown. U, uterus; arrows 1, 2, and 3 point to the ureter; IFP, infundibulopelvic ligament; O, ovary; t, tube; B, bladder; P, psoas major muscle; V, uterine vessels. D. The scissors point to the aorta (A) and fibers of the hypogastric nerve plexus. CI, common iliac artery. E. The large vessels within the retroperitoneal space are well visualized in this photograph. The iliac veins and vena cava are also shown. A, aorta; M, inferior mesenteric artery; CI, common iliac artery; U, ureter; P, psoas major muscle. F. The presacral space is exposed. The arrow points to the middle sacral vessels. The clamp elevates the left internal iliac vein (LIV). A, aorta; RIA, right common iliac artery; LIA, left common iliac artery; IM, inferior mesenteric artery; VC, vena cava. G. The right ureter is elevated by the scissors. The clamp points to the ovarian vessels. The arrow points to the left common iliac vein. CI, common iliac artery (right); C, inferior vena cava; E, external iliac vein; P, psoas major muscle. H. Detail at presacral space. CIA, common iliac artery (right); CIV, common iliac vein (left); C, vena cava. I. The arrow points to the right ureter and the infundibulopelvic ligament. H, hypogastric artery; EV, external iliac vein; EA, external iliac artery; P, psoas major muscle. J. The ureter above the right-angle clamp has been separated from the ovarian vessels (infundibulopelvic ligament [IFP]). P, psoas major muscle; H, hypogastric artery; CI, common iliac artery. K. The arrows point to the right ureter. The clamp elevates the right external iliac vein to expose the obturator fossa (OF), the obturator nerve (ON), and the obturator artery (OA). L. Detailed dissection of the hypogastric artery (H) shows the anterior division (AD), the posterior division (PD), the common trunk with the obliterated umbilical and superior vesical artery (OU, SV), the obturator artery (OA), and the uterine artery (U). The superior gluteal artery (SG) branches from the posterior division (PD).

FIGURE 12–4 The peritoneum has been opened over the terminus of the abdominal aorta (clamp). Both right and left common iliac arteries are clearly seen. The large vein is the left common iliac vein.

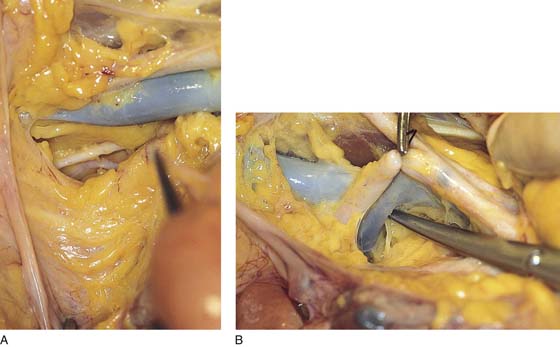

FIGURE 12–5 A. The external iliac artery and vein (blue) cross above the obturator fossa. Removal of some fat and lymph nodes partially exposes the obturator nerve (white) and the obturator artery (pink). B. The anterior division of the hypogastric artery has been ligated. A clamp elevates the hypogastric artery to expose the hypogastric vein. The tip of the scissors is just beneath the junction of the hypogastric and external iliac veins.

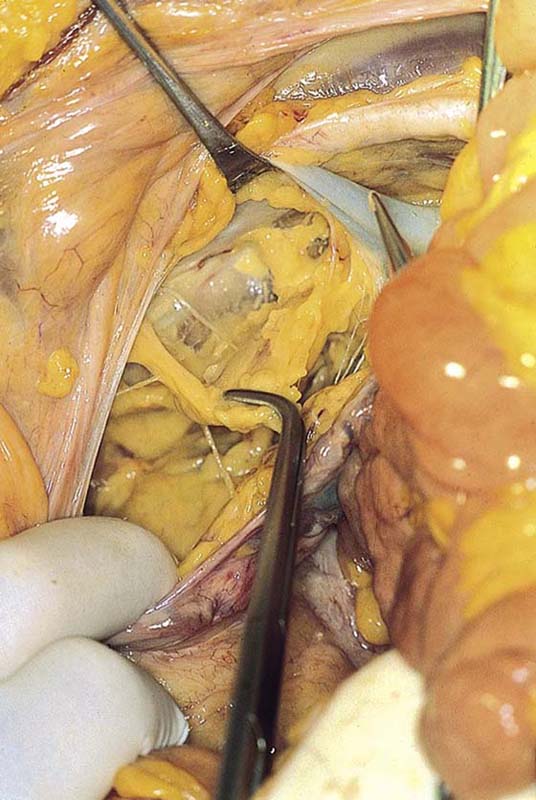

FIGURE 12–6 A vein retractor elevates the external iliac vein. The lymph node–bearing fat is being dissected from the obturator fossa with the clamp. The obturator internus muscle is visible behind the fat.

Radical Hysterectomy and Pelvic Lymphadenectomy

Radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy differ from simple abdominal hysterectomy in two major aspects.

First, the parametria are widely excised, as is the vagina. This requires the ureter to be dissected free for its entire course within the pelvis to the point where the ureter enters the bladder. Additionally, the bladder and the rectum must be separated from the vagina for a distance of 2 to 5 cm below the level of the cervicovaginal junction. Second, the tissues containing fat and lymph nodes are dissected and excised from the external iliac vessels, the obturator fossa, the internal iliac vessels, and the common iliac vessels to the level of the aorta. On occasion, the nodal dissection may expand upward around the aorta to the level of the renal arteries.

The operation is essentially an anatomic exercise.

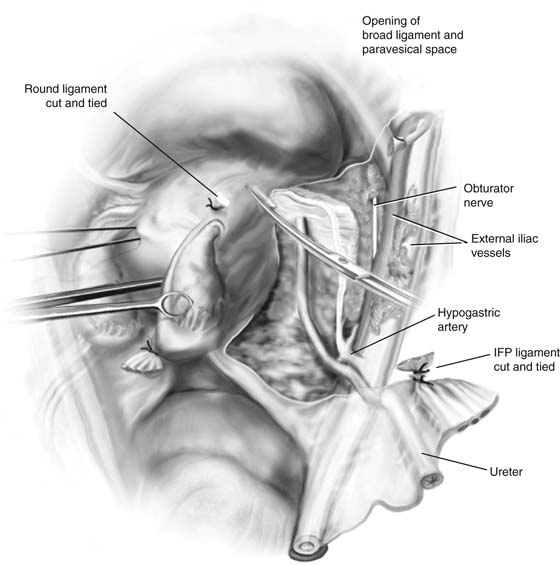

As with simple abdominal hysterectomy (described in Chapter 11), the round ligaments are clamped and divided, and a bladder flap is developed on either side. The top of the broad ligament is incised in a cranial direction. The infundibulopelvic ligament is clamped, transsected, and doubly suture-ligated. If the ovaries are to be saved, the utero-ovarian ligament is clamped, divided, and doubly suture-ligated (Fig. 12–7).

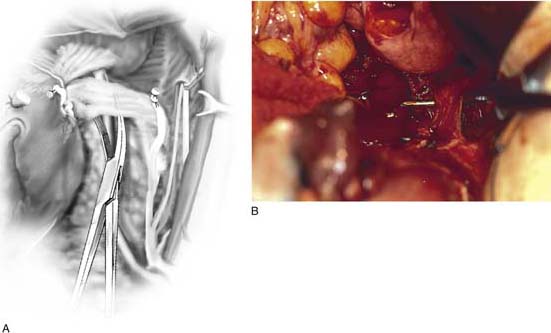

At this point, the peritoneum on the lateral aspect of the broad ligament is dissected further laterally to expose the psoas major muscle. The external iliac artery is then identified and cleared of fat, as is the external iliac vein (Figs. 12–8 and 12–9). During the course of the dissection, the ureter is identified and dissected free at the point where it crosses the common iliac artery to enter the pelvis (Fig. 12–10). The ureter is located posterior to (beneath) the ovarian vascular complex. As the external iliac node dissection proceeds toward the iliac bifurcation, the internal iliac artery is identified and cleared of fat (Fig. 12–11). Care is taken to protect the thin-walled external and internal iliac veins.

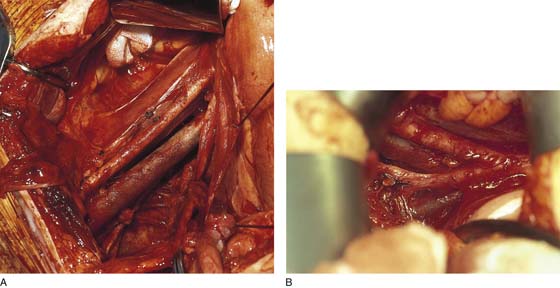

A vein retractor is placed under the external iliac vein and the vein is gently elevated (Fig. 12–12). This exposes the obturator fossa, which is filled with fat and lymph nodes (Fig. 12–13). The fat is dissected out of the fossa, and the obturator nerve and artery are cleaned of fat and lymph tissue (Fig. 12–14). The dissection is carried laterally until the fascia of the obturator internus muscle is reached (Fig. 12–15). Great care must be taken to not tear or otherwise injure the tributaries of the internal iliac veins because they bleed profusely and are very difficult to secure. When the obturator dissection is finished, the operator turns attention to the common iliac node dissection (Fig. 12–16). Again, great care must be taken to not injure the left common iliac vein.

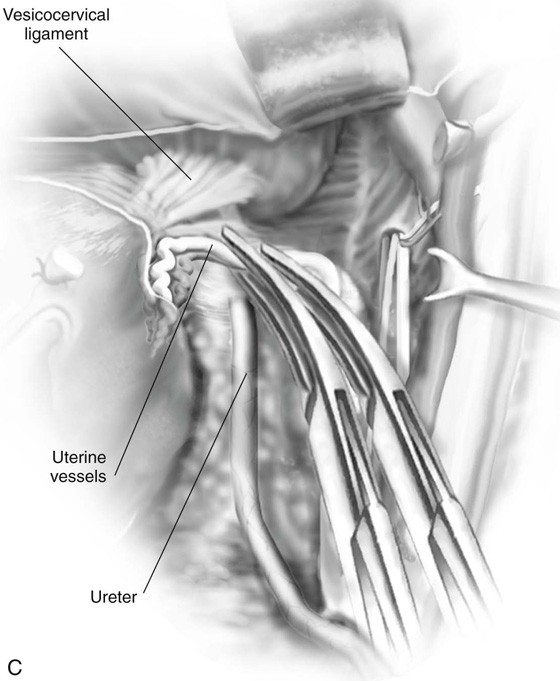

Next, the ureter is dissected inferiorly, with the encompassing fibrofatty tissue removed and medially reflected to be removed with the uterus. The uterine arteries and veins are clamped far laterally, just distal to their origin from the anterior division of the hypogastric artery. If the hypogastric artery is to be clamped, this should be done distal to the origin(s) of the superior and inferior gluteal arteries (Fig. 12–17A–D).

FIGURE 12–7 The round ligament has been clamped, cut, and suture-ligated. The top of the broad ligament has been opened. The psoas muscle under external iliac artery and fat (FAT), external iliac vessels, and ureter have been identified. The upper portion of the paravesical space has been entered lateral to the superior vesical artery. IFP, infundibulopelvic.

FIGURE 12–8 Fat and lymph nodes have been dissected from the external iliac artery and vein. The obturator nerve has been partially exposed.

FIGURE 12–9 In the background is the large, blue external iliac vein. The lymph node–bearing fat is grasped with a ring pick-up, while the surgeon sharply dissects the fatty tissue from the vessels.

FIGURE 12–10 The ureter is dissected inferiorly into the pelvis to the level of the point where the uterine artery crosses over it.

FIGURE 12–11 Medial to the ureter and posterior and inferior to the external iliac artery lies the internal iliac (hypogastric) artery. Nodes and fat are cleared from this vessel.

FIGURE 12–12 Nodal tissue is extracted from the hypogastric artery and vein. The ureter is noted slightly inferior (below) and medial. The vein retractor is seen to the left and above the yellow electrosurgical pencil. The retractor gently elevates the slate blue external iliac vein.

FIGURE 12–13 Fat and nodes are now pulled from the obturator fossa. This is done by gently teasing the tissue from the space using ring pick-ups. The external iliac vein is retracted upward by means of gentle traction on a vein retractor.

FIGURE 12–14 A and B. The obturator nerve is in clear view. Note the ureter at the lower margin of the picture. Its course parallels the obturator fossa structures with the exception that the obturator nerves and vessels assume a somewhat elevated course as they leave the pelvis via the obturator foramen. The ureter, on the other hand, descends deeper into the pelvis, vectoring toward the bladder base.

FIGURE 12–15 A. The node dissection of the obturator fossa is complete, as is the dissection of the external iliacs. Beneath the external iliac vein and deeply lateral is the obturator internus muscle. B. The internal iliac (hypogastric) artery and vein have been cleaned of fat and lymph nodes. Note the location of the vein (hypogastric).

FIGURE 12–16 The common, external iliac, and internal iliac arteries and veins have been dissected. The obturator nerve marks the dissected obturator fossa. The ureter is visible at the lower margin of the figure.

FIGURE 12–17 A. The posterior division of the hypogastric artery has been exposed. B. The origin of the uterine artery from the anterior division of the hypogastric artery is isolated above the tonsil clamp. C. The uterine artery is clamped lateral to the pelvic ureter. D. The uterine artery is cut and doubly ligated. The veins are typically ligated with the artery but may be separately clamped, divided, and tied.

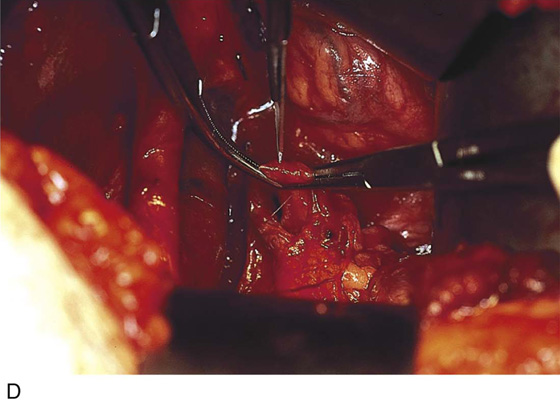

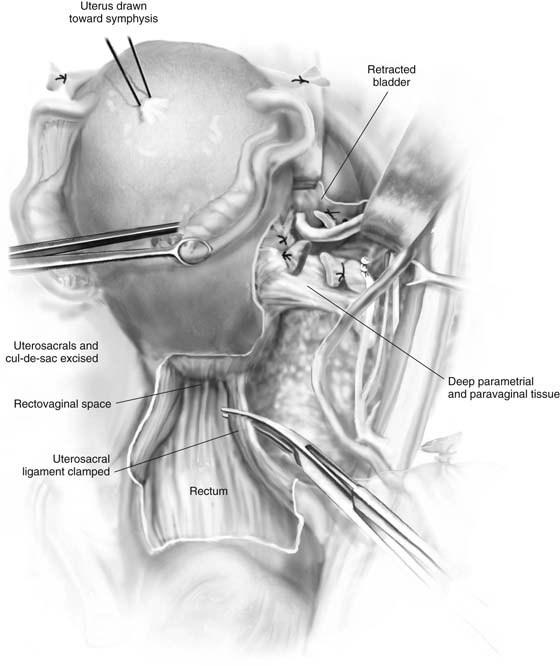

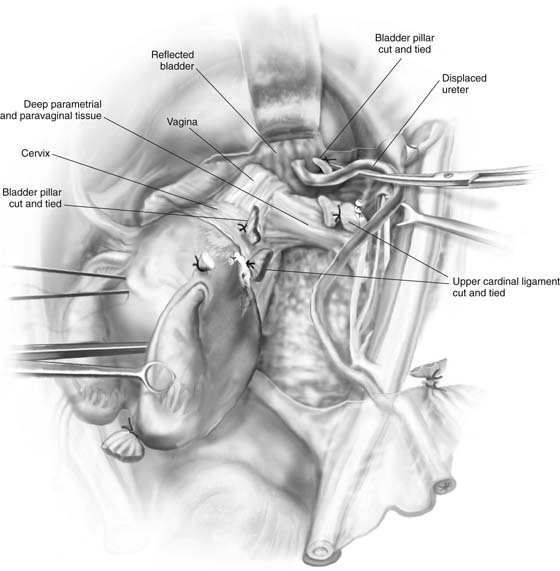

At this point, the ureter is entering its tunnel through the cardinal ligament just cephalad to where it enters the wall of the bladder (Fig. 12–18A, B). The tunnel is unroofed by means of right-angle and tonsil clamps and Metzenbaum scissors (Fig. 12–19A–C). The pedicles are secured with 3-0 Vicryl suture ligatures (Fig. 12–20A). The ureter is now free of the parametria (Fig. 12–20B). Next, the bladder pillars are identified, cut, and secured (Fig. 12–21). The vesicouterine space is dissected downward well below the uterine cervix.

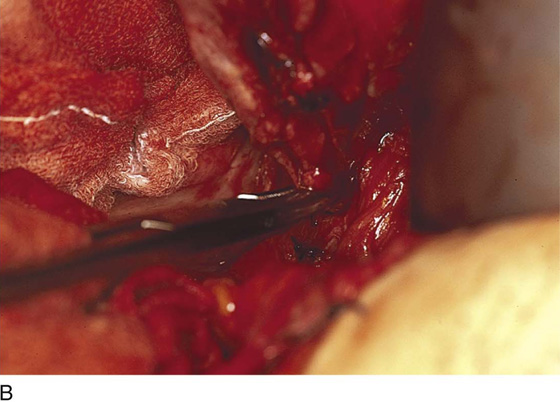

The peritoneum between the uterosacral ligaments is divided and the rectouterine space is developed and dissected downward below the cervix. The uterosacral ligaments are cut and suture-ligated (Fig. 12–22).

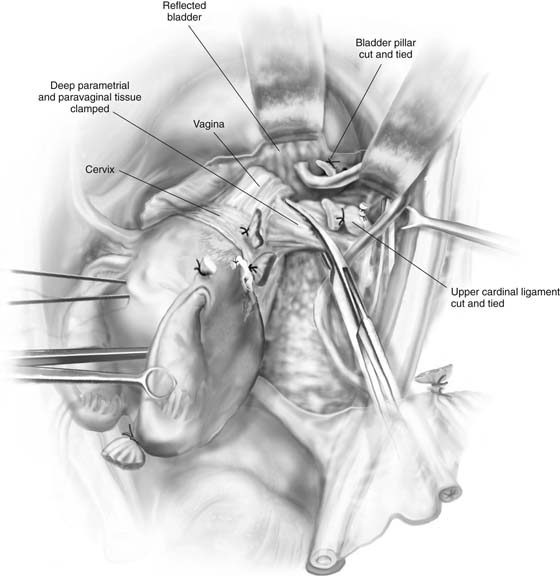

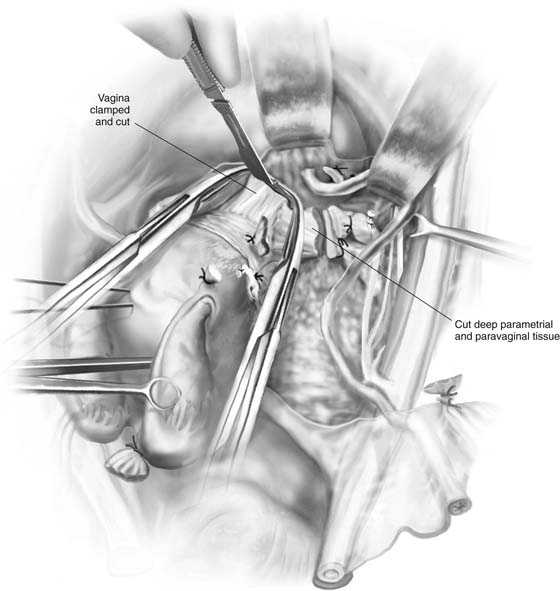

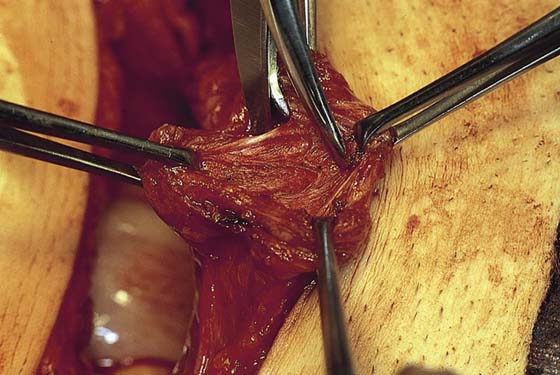

The lower cardinal ligament, deep parametrial (paravaginal) fat, and fascia are clamped and cut medial to the ureter (Fig. 12–23). The vagina is clamped approximately 4 cm below the cervix, and the specimen is removed (Figs. 12–24 through 12–26). The anterior and posterior peritonei are closed with 3-0 Vicryl. The retroperitoneum is drained (Fig. 12–27). A suprapubic catheter is placed and the abdomen closed by means of the Smead-Jones technique or a suitable substitute (Figs. 12–28 through 12–31).

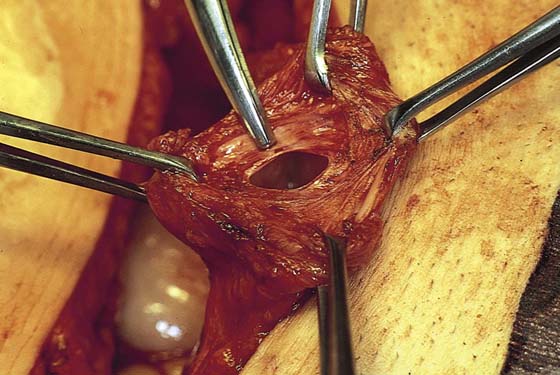

FIGURE 12–18 A. The ureter is dissected to the level of the cardinal ligament. At this point, the ureter penetrates the cardinal ligament in its short course to the bladder. The “tunnel” is dissected by inserting a right-angle clamp between the ureter and the roof of the tunnel (cardinal ligament). B. The roof of the ureteral tunnel is stretched with tonsil clamps before the edges of this tissue are clamped.

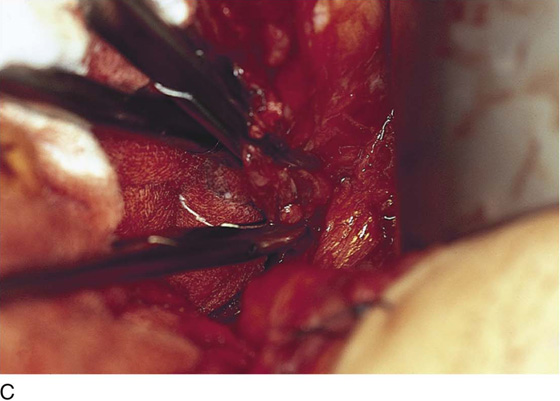

FIGURE 12–19 A. When the ureter is clearly freed from the roof of the tunnel, the ligament margins above the ureter are clamped with tonsil clamps. B. A tonsil clamp is placed at the lateral edge of the tunnel before it is cut. C. The tunnel is being cut with Metzenbaum scissors. A knife can be used if the ureter is covered by the closed right-angle clamp.

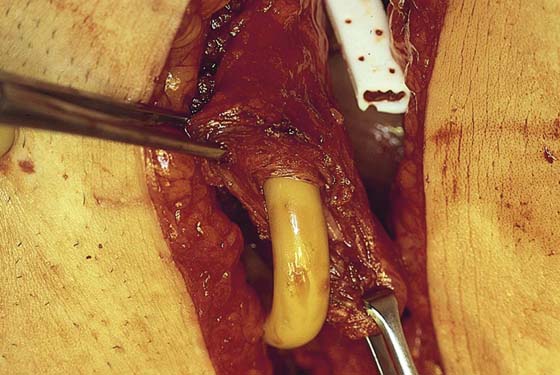

FIGURE 12–20 A. The cut edges of the cardinal ligament are suture-ligated with 0 Vicryl, and the ureter is freed from the posterior bed of the ligament. B. The ureter is entirely free and mobile as it makes its way under the bladder pillar to enter the urinary bladder.

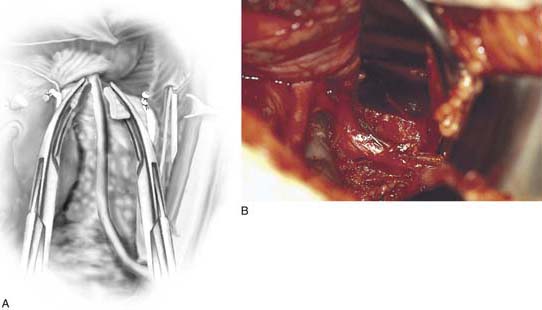

FIGURE 12–21 The bladder pillar has been divided. Each portion will be suture-ligated with 0 Vicryl.

FIGURE 12–22 The uterosacral ligaments are clamped. The peritoneum between the two uterosacral ligaments is cut, and the rectovaginal space is dissected. The uterosacral ligaments are cut, and the stumps are suture-ligated with 0 Vicryl.

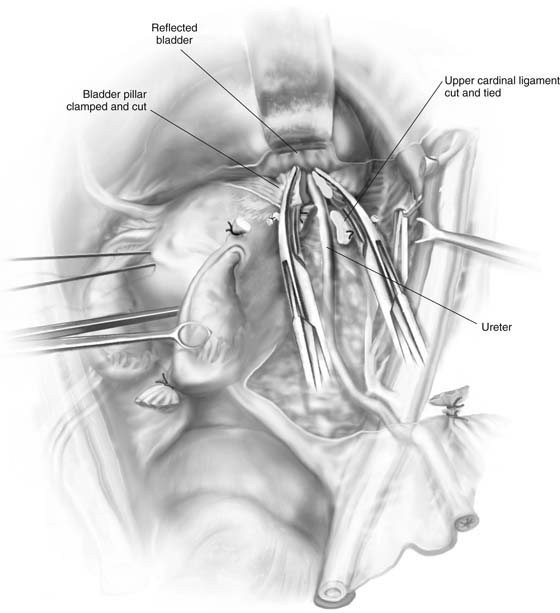

FIGURE 12–23 The lateral parametrial tissue is located below the cervix and is attached to the lateral walls of the vagina. The ureter is retracted to permit the surgeon to expose this tissue.

FIGURE 12–24 A long, curved Zeppelin clamp grasps the tissue. Long Mayo scissors are utilized to cut the tissue medial to the applied clamp. The final clamp will be placed across the vagina.

FIGURE 12–25 Zeppelin clamps are placed across the vagina approximately 4 cm inferior to (below) the fornices. The vaginal attachment is severed, and the uterus, together with the attached parametria, is removed.

FIGURE 12–26 The bladder dome is grasped and a small cystotomy is created.

FIGURE 12–27 Through this small opening, a Foley (suprapubic) catheter will be introduced.

FIGURE 12–28 The catheter is secured by a purse-string suture. The upper edge of the incision shows the tip of the drain, which is placed retroperitoneally before the peritoneum is closed.

FIGURE 12–29 The abdominal incision is closed. The suprapubic catheter and Jackson-Pratt drains are brought out via separate stab wounds.

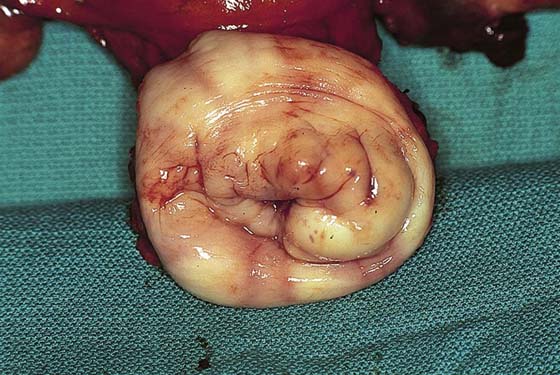

FIGURE 12–30 The excised specimen includes parametria, paravaginal tissue, and an adequate vaginal margin of tissue.

FIGURE 12–31 The cervix and attached 4-cm vaginal cuff.

Michael S. Baggish

Michael S. Baggish