Radical Cystectomy

Surgical Approach

Bladder Mobilization

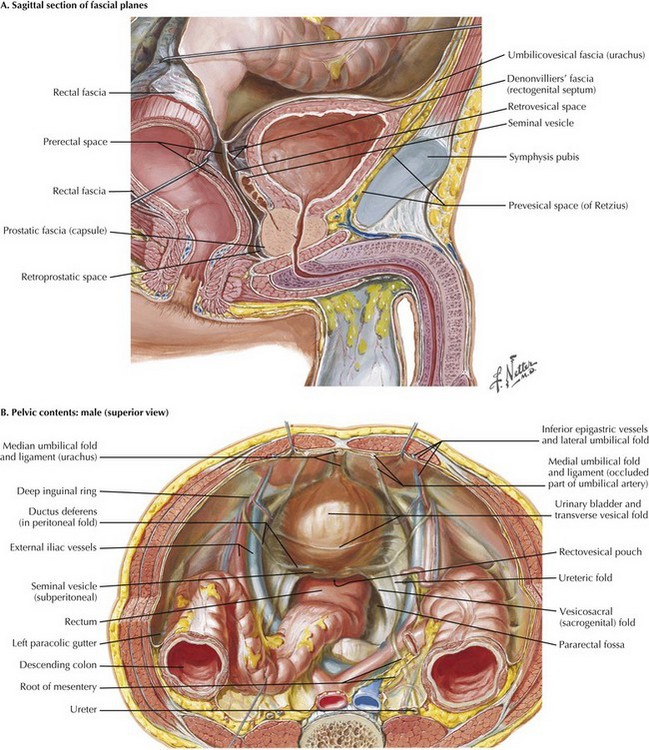

With the medial umbilical ligaments traced inferiorly and the space of Retzius open, a self-retaining retractor can be placed to facilitate exposure. Extra care is taken when applying traction on the most inferior aspect of the wound; injury to the femoral and genitofemoral nerves can result from prolonged stretch or compression. The symphysis should be visible with the retractor in place (Fig. 55-1, A).

The peritoneal wings previously left in place by developing the space of Retzius and opening the peritoneum from the umbilicus to the inguinal ring are easily seen and divided with electrocautery to the level of the vas deferens in the male patient. The vas deferens is divided with the understanding that vascular structures are associated with both vasa. The authors prefer to use ties to allow later identification of the seminal vesicles (Fig. 55-1, B).

Dissection of Ureters

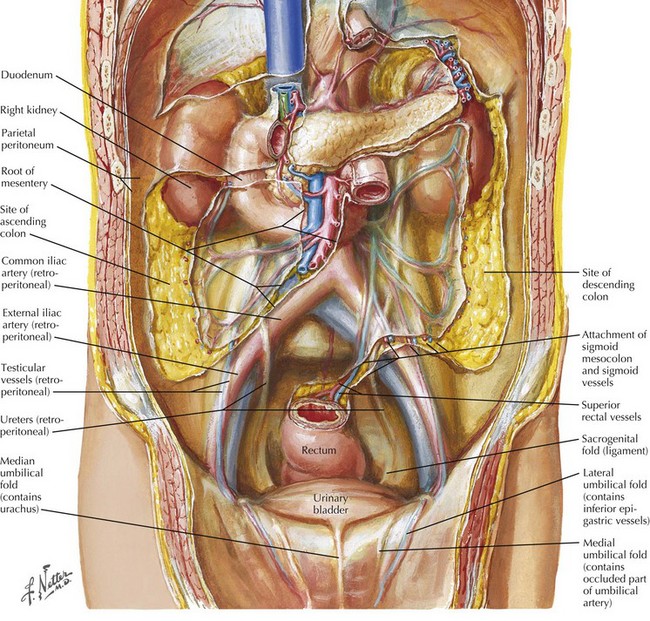

The left ureter is identified posterior to the sigmoid colon, in a position often more medial than expected. The retroperitoneal space behind the sigmoid colon at the level of the sacral promontory is opened to allow the ureter to be passed to the other side after its division. The right ureter is found by dividing the visible peritoneal fold overlying it (Fig. 55-2).

Pelvic Lymphadenectomy

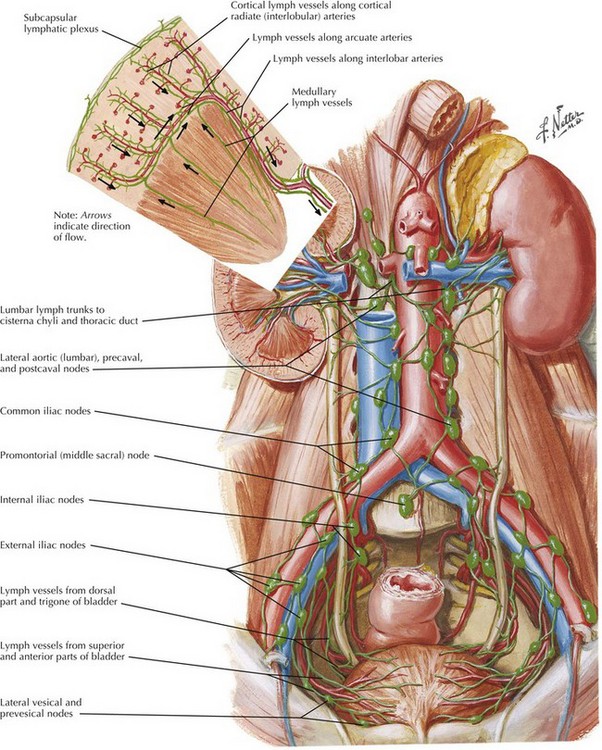

Limits of the lymphadenectomy are often variable depending on extent of disease. It has been demonstrated that 25 to 30 nodes should be resected to determine nodal status, and that this can be curative in some cases of micrometastatic nodal disease. The most limited dissection should at least include all fibroadipose and lymphatic tissue between the external iliac artery laterally, the internal iliac artery medially, the crossing of the ureter at the common iliac artery cranially, the circumflex iliac vein or inguinal ligament of Cooper caudally, and the obturator nerve inferiorly. More extensive dissection can extend to the genitofemoral nerve laterally and the bifurcation of the aorta cranially or even to the inferior mesenteric artery (Fig. 55-3).

Pedicle Dissection

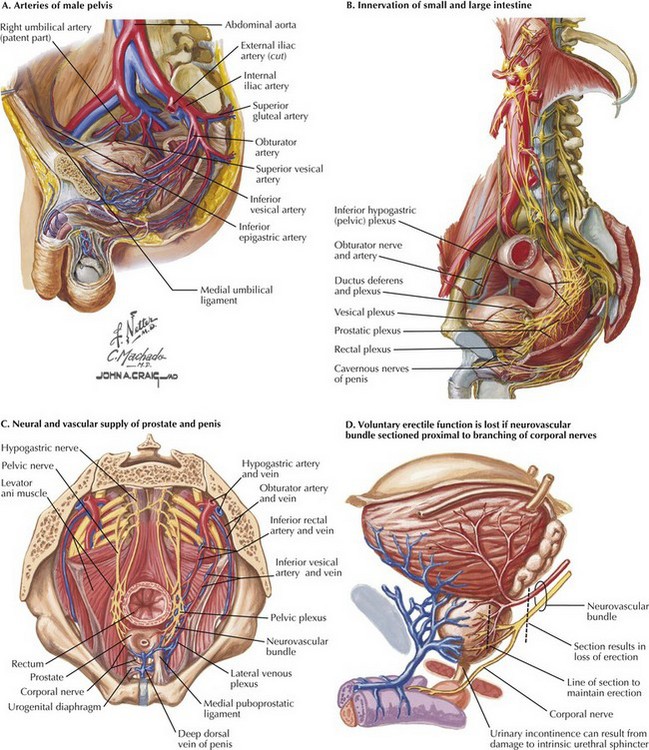

Knowledge of vascular anatomy is the key to successful dissection of the lateral and posterior pedicles of the bladder. With the internal iliac artery already exposed and the vas deferens divided, the superior vesical artery, the first anterior branch of the internal iliac artery, can be safely ligated near its branching from the internal iliac artery (Fig. 55-4, A).

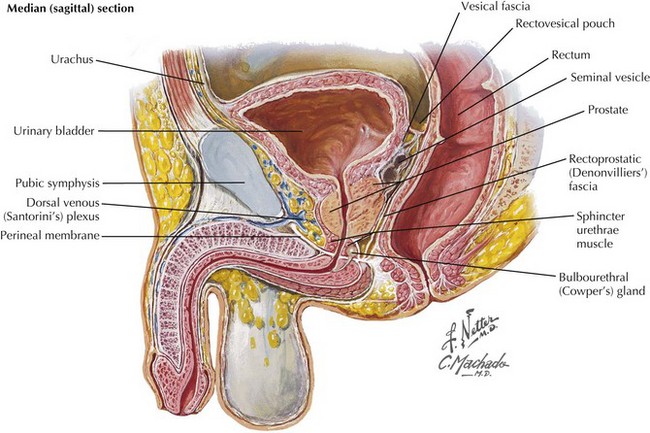

The space posterior to the prostate is developed caudally as close to the prostatic apex as possible. Here the surgeon may choose to continue with either nerve-sparing or non–nerve-sparing technique. Care should be taken to avoid damaging any of the autonomic nerves from the pelvic plexuses, because these nerves innervate the urinary sphincters and will play an important role in postoperative continence if an orthotopic urinary diversion is constructed (Fig. 55-4, B).

To preserve the autonomic plexus, an incision should be made between the lateral pelvic fascia and Denonvilliers’ fascia to find the neurovascular bundles that lie posterolaterally along the prostate (Fig. 55-4, C and D).

Urethral Ligation

Continuing caudally from the previously developed space of Retzius, the space anterior to the prostate is first opened, and the prostate is separated from its anterior attachments to the pubis. The endopelvic fascia and puboprostatic ligaments are exposed anteriorly, and the endopelvic fascia is opened, revealing the muscular attachments of the levator muscles to the prostate. With the endopelvic fascia open bilaterally, the anterior prostatic fascia, the extension of the endopelvic fascia over the prostate, can be suture-ligated. The dorsal venous complex (Santorini’s plexus) is located within this fascia (Fig. 55-5).

Anterior Pelvic Exenteration

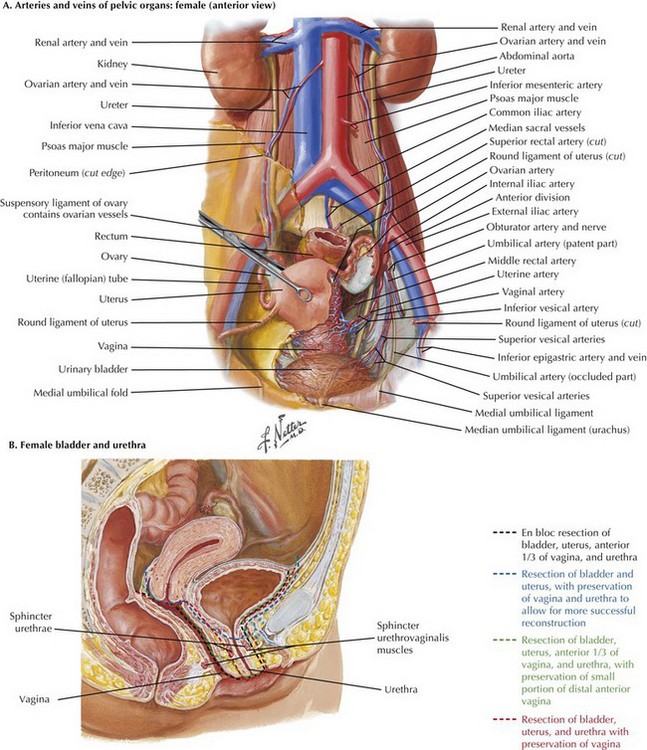

First, the ovarian vessels and infundibulopelvic ligaments are ligated, which allows for better exposure because the intestines can be packed upward into the abdomen away from the pelvis. The ureters are traced to the vascular supply of the uterus. The uterine vessels are suture-ligated at their origin from the internal iliac vessels to mobilize and expose the ureters to the ureterovesical junction, where they are ligated (Fig. 55-6, A).

Bladder Mobilization

The authors’ preference is to spare the anterior vaginal wall when the disease appears confined to the bladder or when cystectomy is being performed for benign disease. If vaginal sparing is not possible, on entering the vagina anteriorly, the surgeon can divide the lateral bladder pedicles en bloc with the anterior wall of the vagina, using thermal dissectors or suture ligation (Fig. 55-6, B). Staples and clips should be avoided in this situation because these objects may migrate into the vagina postoperatively.

Vagina-Sparing Technique

Alternatively, if the vagina is to be spared fully, or in cases of limited disease and previous hysterectomy, the space between the anterior vagina and the posterior bladder wall is developed, taking care to dissect closely to the anterior vaginal wall. If hysterectomy is required, a circumferential incision of the vagina close to the vaginal apex allows for removal of the cervix and uterus. Closure of the vagina depends on the method of urethrectomy described below (Fig. 55-6, B).

Urethrectomy

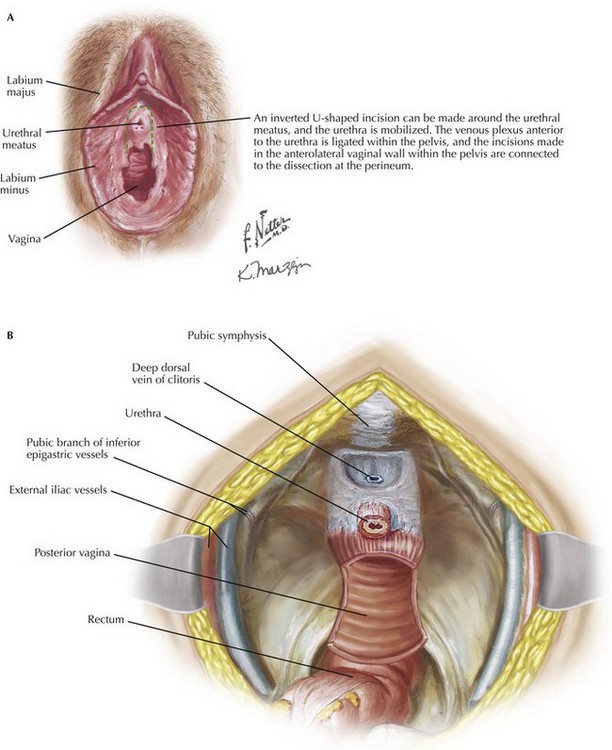

The labia are retracted laterally to expose the urethra. If vagina-sparing techniques are not used, a U-shaped incision can be made from the top of the introitus surrounding the anterior vaginal wall and carried around the urethra (Fig. 55-7, A). Within the pelvis, the pubourethral suspensory ligaments, corresponding to the puboprostatic ligaments in men, are ligated to release the bladder and urethra. The dorsal vein complex superior to the urethra is isolated and ligated. Any other periurethral attachments are released circumferentially and passed in continuity through the vaginal incision in to the pelvis.

Alternatively, a circular incision can be made around the urethra. The portion of the anterior vagina below the bladder neck is left in the pelvis to support the reconstruction of the vagina. The urethra is sharply dissected off the anterior vaginal wall and, after ligation of all other periurethral attachments, passed in to the pelvis (see Fig. 55-6, B).

Vaginal Reconstruction

When the anterior wall of the vagina is removed, vaginal reconstruction is necessary. Classically, and the authors’ preference, is to fold the posterior wall of the vagina toward the apex as a flap for coverage of the introital defect (Fig. 55-7, B). The reconstruction is completed with an absorbable suture, typically 2-0 Vicryl or its equivalent. This maneuver obligatorily shortens the vagina.

Chang, SS. Radical cystectomy. In: Smith J, Howards SS, Preminger GM, Hinman F, eds. Hinman’s atlas of urologic surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders-Elsevier, 2012.

Gakis, G, Efstathiou, J, Lerner, SP, et al. Radical cystectomy and bladder preservation for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol. 2012.

Ghonheim, MA. Radical cystectomy in men. In: Graham SD, Keane TE, eds. Glenn’s urologic surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

Weizer, AZ, Lee, CT. Radical cystectomy in women. In: Graham SD, Keane TE, eds. Glenn’s urologic surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2009.