Chapter 10 Radial Nerve

Anatomy

Radial Nerve Origin at the Brachial Plexus

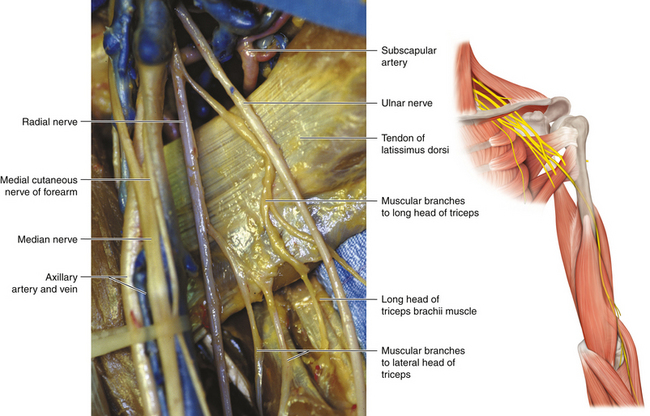

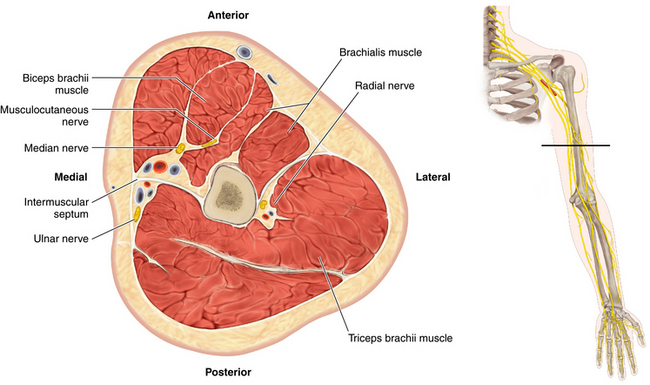

• The radial nerve is formed from the posterior divisions of the brachial plexus and is the larger of the two terminal branches of the posterior cord. Receiving contributions from the C5 to T1 spinal nerves, the radial nerve lies posterior to the third portion of the axillary artery at its origin, on the front of the subscapularis, teres major, and latissimus dorsi muscles.

• The fascicles destined for the axillary nerve and the nerve to latissimus dorsi stick to the posterior cord to varying degrees.

• The coracoid process is a reliable landmark at which the radial nerve continues as the main outflow of the posterior cord, posterior to the axillary artery.

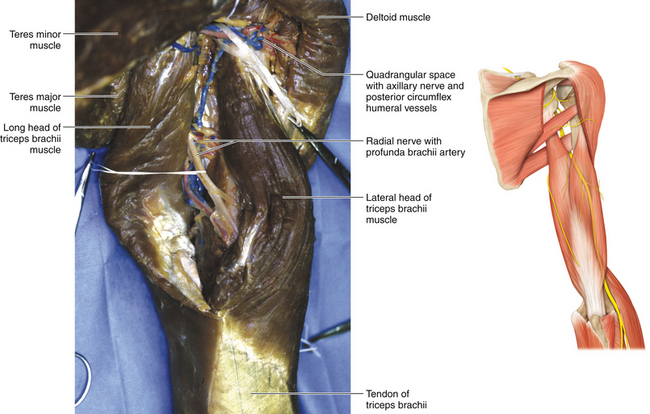

• Close to its origin, the nerve lies on the subscapularis. In its proximal course, the nerve is crossed by the subscapular artery. The size of this stubby vessel varies, and it can be retracted to display the departure of the axillary nerve. The radial nerve lies on the familiar, shiny surface of the latissimus dorsi tendon and then crosses in front of the teres major as the nerve heads, posterior to the subscapular artery, toward the upper end of the spiral groove (Figure 10-1). It courses in front of the long head of the triceps.

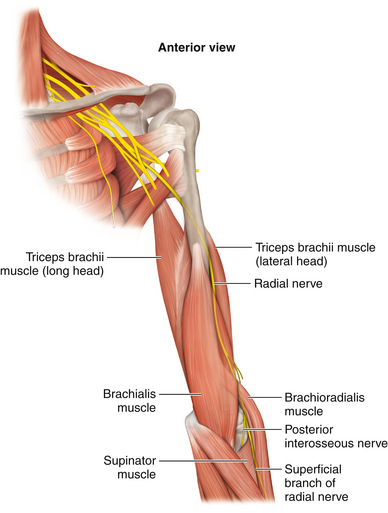

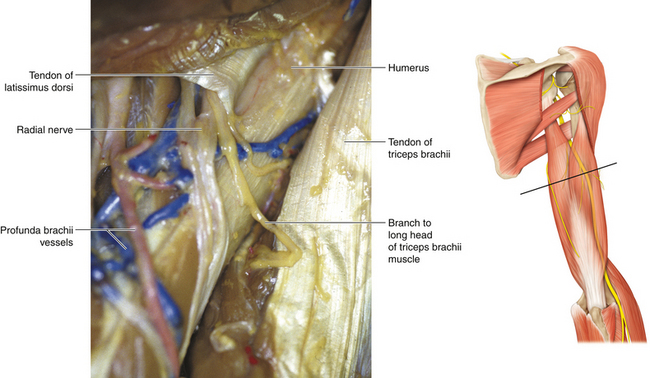

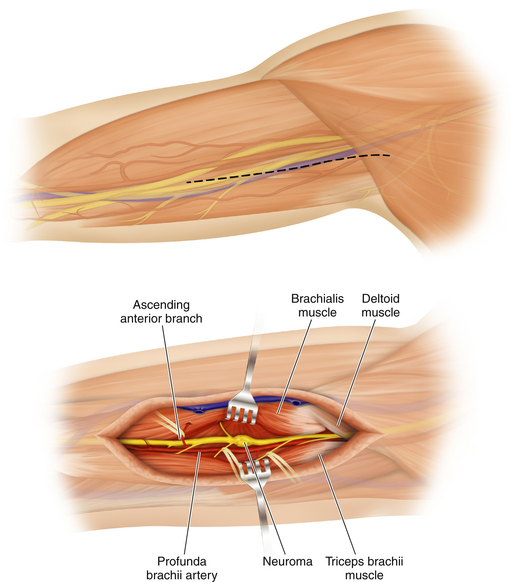

• Also near its origin, the radial nerve gives off a variable number of branches to the triceps. Proximally, the nerve lies behind the brachial artery and in front of the triceps muscle; it deviates from the brachial artery at the point where the nerve winds around the posterior aspect of the humerus from the medial to the lateral side of the arm. The radial nerve passes with the profunda brachii artery through a triangular space bounded by the humerus laterally, the long head of triceps medially, and the teres major superiorly (Figure 10-2).

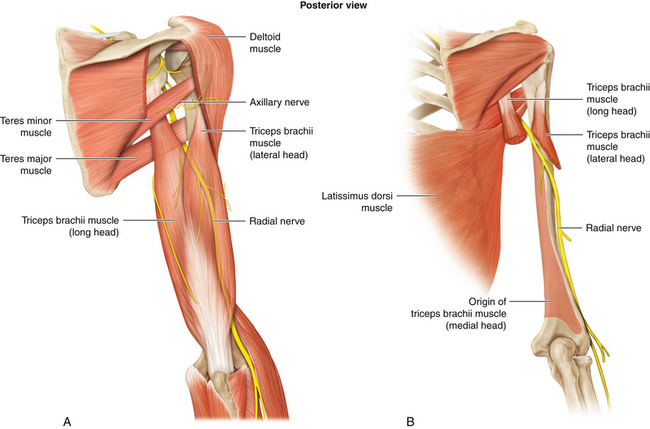

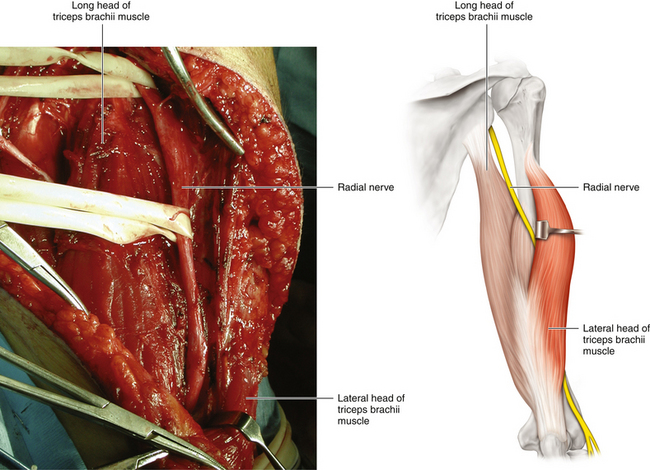

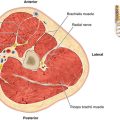

• At the posterior aspect of the humerus, the radial nerve lies in the spiral groove, deep to the long head of the triceps and between the lateral and medial heads. This is the point at which it has the fewest number of fascicles (approximately four or five) in its entire course (Figures 10-3 and 10-4).

• The anatomy (and confusing nomenclature) of the triceps should be clearly understood. The origin of the medial head borders the medial extent of the spiral groove of the humerus. When viewed from behind, the lateral and long heads of the triceps lie side by side, covering the radial nerve, its accompanying profunda brachii artery, and the medial head of the triceps.

• All three heads of the triceps are supplied by the radial nerve, and the surgeon should be aware that these motor branches may leave the radial nerve proximally, as well as in the nerve’s course around the humerus. The anconeus is supplied by a long branch of the radial nerve in the spiral groove. Electromyography of this small muscle may help determine the exact point of pathology along the course of the radial nerve.

• Throughout its course in the spiral groove, the radial nerve is accompanied by the profunda brachii artery.

• The nerve then runs through the lateral intermuscular septum to gain the flexor compartment of the distal arm (Figure 10-5).

Radial Nerve at the Elbow

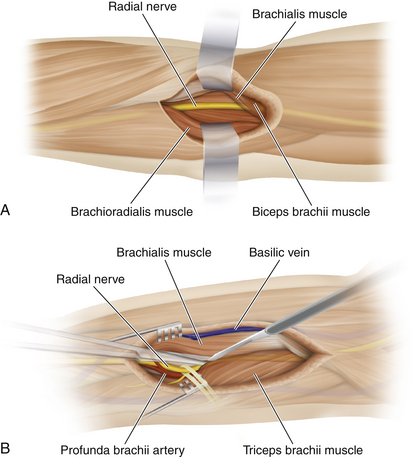

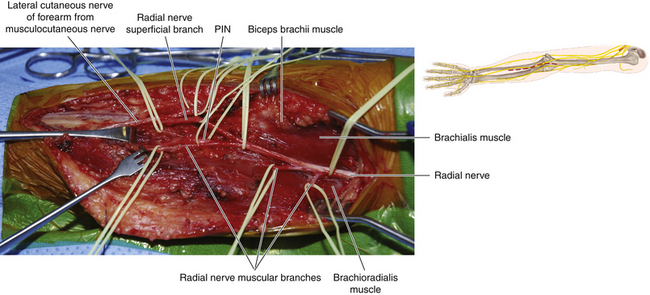

• Lying first in the groove between brachialis and brachioradialis, the radial nerve then descends between the brachialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus to pass in front of the lateral epicondyle into the forearm. The radial nerve gives branches to the brachialis from its medial aspect. The brachialis receives dual innervation from the musculocutaneous nerve and the radial nerve.

• The radial nerve supplies the brachioradialis and the extensors carpii radialis longus and brevis. Muscular branches to the brachioradialis are given off 2 to 3 cm proximal to the elbow.

• When viewed from the front, the radial nerve is easily found lateral to the humerus. The surgeon’s thumb displaces the brachioradialis laterally while the brachialis is displaced medially with the other thumb. The radial nerve will be found at the bottom of this trough (Figure 10-6).

• In patients who are not obese, the radial nerve can be rolled against the humerus as it exits the spiral groove (see Figure 10-5).

Origin of the Posterior Interosseous Nerve

• Note carefully the origin of the ulnar head of the supinator. The muscle fibers wrap around the posterior aspect of the proximal radius and, after embracing the lateral aspect of the proximal radius, are inserted between the anterior and posterior oblique lines of the radius. The superficial head of the supinator is derived from the distal humerus.

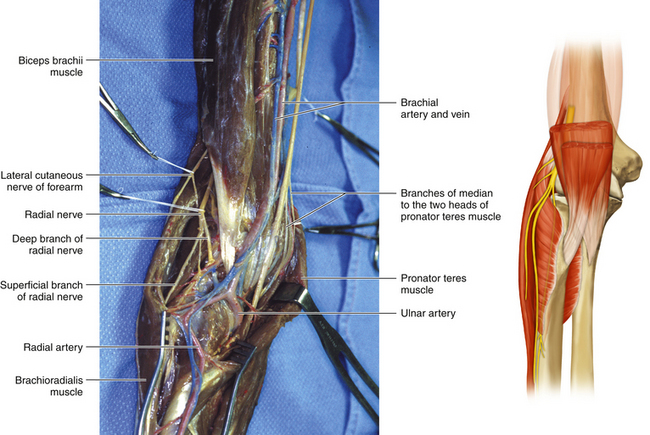

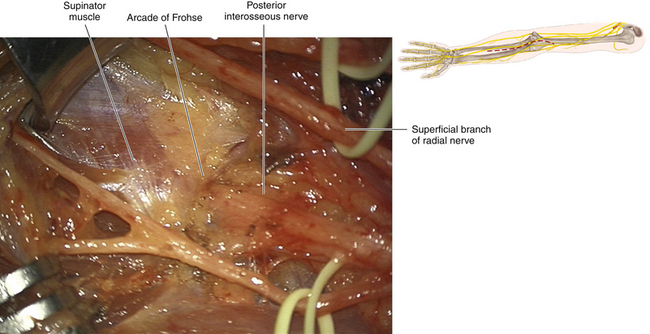

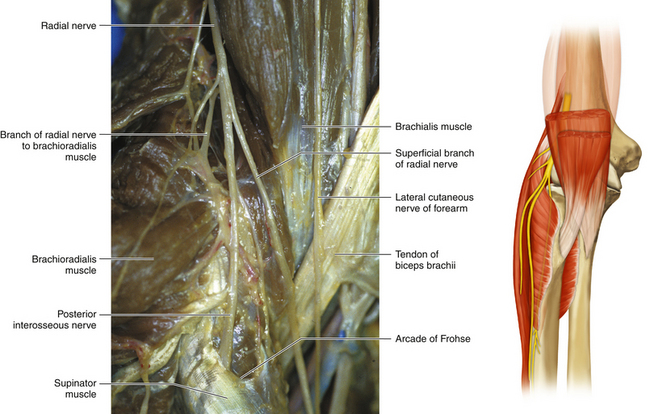

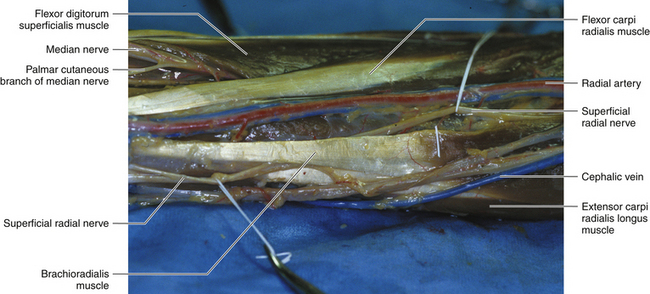

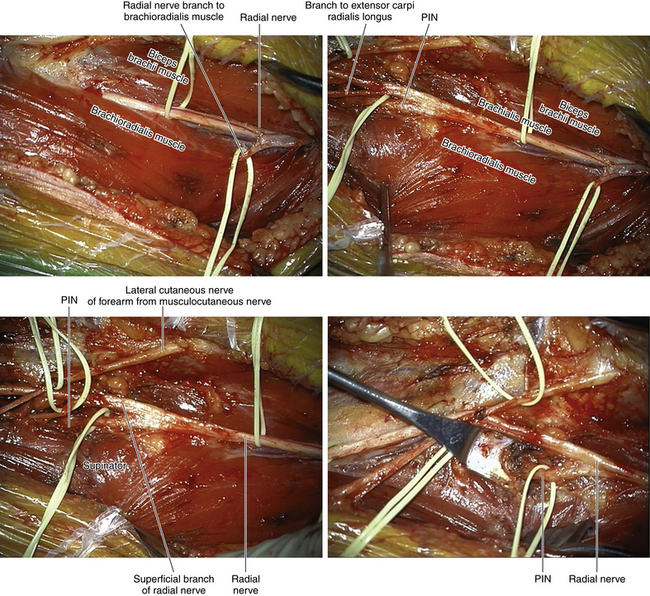

• The radial nerve divides into two terminal branches: the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN), which is the deep branch of the radial nerve, and the superficial sensory radial nerve (Figures 10-7 and 10-8).

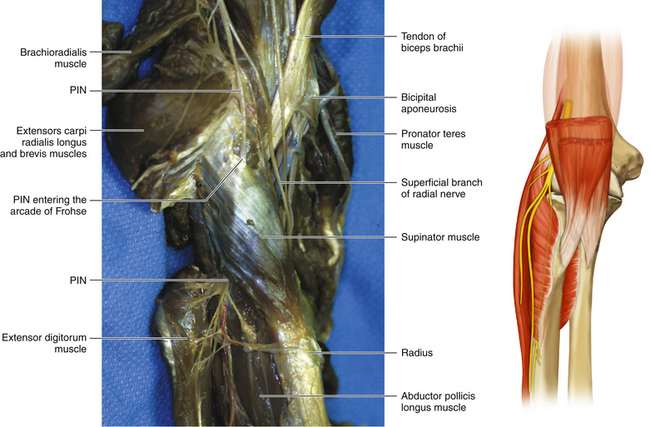

• The PIN passes between the superficial and deep laminae of the supinator muscle. The supinator has two heads of origin. The superficial (humeral) head has an upper border of variable consistency (muscular, fibrous, or tendinous—the arcade of Frohse). A number of small arterial branches are found at the point where the nerve enters the tunnel between the two heads of the supinator.

• Whereas the branch of the radial nerve to the brachioradialis characteristically leaves the radial nerve from its lateral side, the motor branches to extensors carpii radialis longus and brevis may leave the radial nerve, the PIN, or the superficial sensory radial nerve (or combinations thereof). The motor branches to the supinator may arise proximal to the arcade of Frohse (Figure 10-9) or in the PIN’s course between the two layers of supinator.

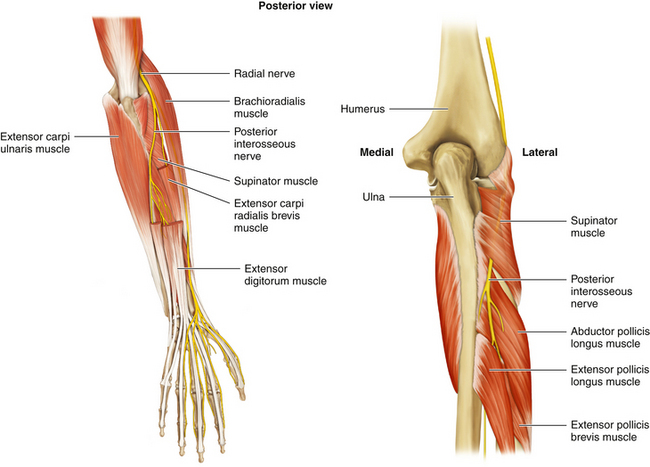

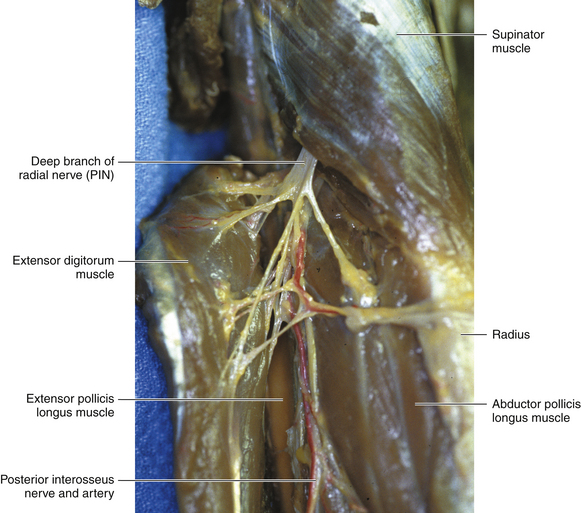

• The nerve exits the supinator tunnel and comes to lie between the superficial and deep extensor muscles on the posterior aspect of the forearm. Characteristically, the nerve breaks into numerous fine branches at this point to supply those individual muscles (Figure 10-10).

• One major component supplies the more superficial layer of muscles (extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, and extensor carpi ulnaris) and the second innervates the deeper muscles (abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus and brevis, and extensor indicis) (Figures 10-11 and 10-12).

The Superficial Sensory Radial Nerve

• The superficial sensory radial nerve (SSR) is a direct continuation of the radial nerve. The SSR is easily identified in the forearm as it descends under the edge of the brachioradialis.

• The SSR runs distally under cover of the medial border of the brachioradialis. A few inches proximal to the radial styloid, the terminal sensory branches turn backward under the brachioradialis tendon of insertion and cross the long extensors of the thumb (against which they can be palpated) (Figure 10-13).

• The distal branches of the SSR run posterior to the scaphoid bone. They cross the anatomical snuffbox and supply a variable area of skin over the dorsum of the hand, the area not supplied by the ulnar and median nerves.

Surgery of the Radial Nerve

Skin Incision

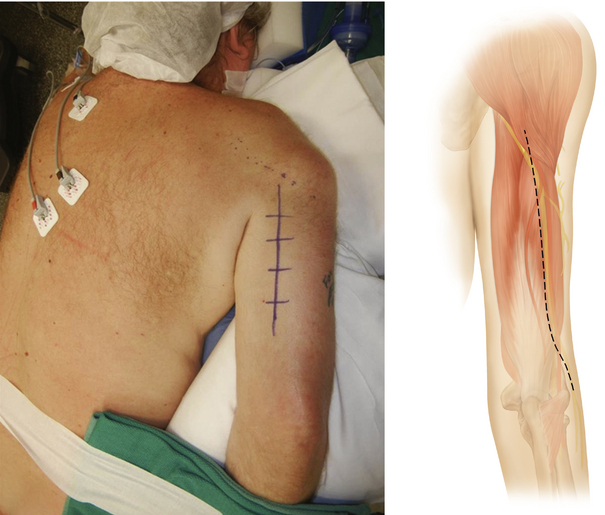

• The nerve is approached in the upper arm through a skin incision over the course of the nerve (Figure 10-14). The nerve must be distinguished from the median and ulnar nerves. It is the most posterior of the three and makes its way toward the upper end of the spiral groove. (The humerus is palpable and acts as a guide.)

• The nerve is approached from the posterior aspect by an incision that parts the long and lateral heads of the triceps (Figures 10-15 and 10-16).

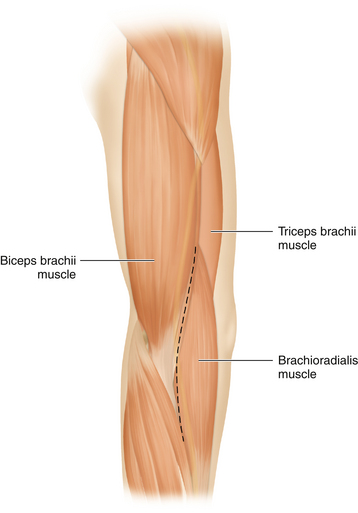

• The nerve is approached in the lateral distal arm by an incision in the space between the brachialis and brachioradialis (Figure 10-17).

• In the forearm the nerve is exposed on the flexor and extensor aspects, usually through two separate incisions, although a single skin incision can be fashioned to allow access to both the flexor and extensor compartments.

• These various incisions may either be joined or used separately; for example, it is common practice to expose the proximal radial nerve medially and the distal nerve laterally, and then work from both sides to expose the nerve at the point of pathology, posterior to the humerus.

Arm Surgery

• Isolated injuries of the proximal radial nerve are repaired using standard peripheral nerve surgical technique.

• A common problem, however, is a nerve injury at the level of the posterior humerus. In this situation the radial nerve is followed to the spiral groove, where the surgeon’s fingertip then encounters scar, callus, plate, or screw, depending on the circumstances.

• The nerve is then exposed in the distal arm, lateral to the humerus. The nerve is usually displayed by retracting the brachialis and brachioradialis and finding the nerve at the bottom of that trough. If a problem is still encountered, the superficial sensory radial nerve is easily displayed by dissecting the medial border of the brachioradialis in the proximal forearm. This reveals the sensory nerve, and it can be followed up proximally to the main nerve.

• It is essential that motor branches to the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles be respected during these maneuvers (Figure 10-18).

• The surgeon’s fingertips, from the lateral and medial exposures, should meet at the area of pathology. The nerve is then stimulated. If no response is obtained in the first target muscle (brachioradialis), nerve action potential recordings are made with stimulating and recording electrodes on either side of the humerus.

• In the absence of electrophysiological evidence, the proximal nerve is cut through viable tissue as close as possible to the area of pathology, as is the distal nerve.

• A tunnel is then created deep to the biceps, so that the distal stump can be brought through the tunnel in an attempt to directly oppose the distal and proximal stumps on the medial side of the arm. If this is impossible (usually the case), grafts are utilized. The grafts should be positioned in front of the humerus before any suturing, or else previous suture lines may be disrupted by the subsequent passage of additional grafts.

Posterior Interosseous Nerve

• After the medial border of the brachialis is cleared, the radial nerve is exposed in the distal arm and the SSR is displayed in the proximal forearm. The surgeon then gently tents both nerves upward and works toward the center from either end; the PIN will be found running away from the surgeon to the upper border of the superficial head of the supinator (Figure 10-19).

• The nerve typically gives off supinator branches proximal to where the nerve disappears between the two heads of the supinator. These must be guarded. Characteristically, there are several small arterial branches; these should be divided to allow an absolutely clear view of the nerve at the entrapment site. The superficial head of supinator is then divided while protecting the underlying PIN and its branches. An instrument is then passed along the course of the nerve; the tip of that instrument will be seen tenting up the skin on the posterior aspect of the forearm.

• Using this guidance, a vertical incision is made over the course of the PIN and the superficial extensors are parted to reveal the terminal branches of the PIN. If the pathology is PIN entrapment, the entire superficial head of the supinator is divided, using anterior and posterior incisions.

• If there is irreparable pathology, grafts are utilized. Difficulty may be encountered in defining a distal stump where the nerve exits the supinator. Characteristically, many fine branches arise as individual motor branches for the various muscles in the extensor compartment. The surgeon should therefore be at pains to preserve, if at all possible, either the main trunk of the nerve or one of the two main branches, because it is very difficult to bring grafts through to the fine individual muscle branches.

• If grafts are required, they should be placed between the proximal and distal stumps before any suturing is commenced, so that nothing disturbs either the proximal or distal suture lines once they are completed.

• If the radial nerve injury is in the distal arm proximal to the PIN takeoff, the SSR is separated away in the distal stump so that all regenerating motor fibers are captured by the PIN and do not stray into the SSR.

SSR

• The radial nerve terminates by dividing into the SSR and PIN. In about half of patients, the branches to the extensor carpi radialis (ECR) leave the radial nerve just before its bifurcation into the SSR and PIN; in the other half, this branch to the ECR forms from the proximal portion of the SSR.

• The SSR takes a more superficial course than the PIN and lies beneath the brachioradialis, running down the radial side of the forearm (it is a useful donor nerve, in appropriate cases).

• At the junction of its middle and distal thirds, the SSR leaves the cover of the tendons and runs toward the anatomical snuffbox formed by the tendons of extensor pollicis longus and abductor pollicis longus.

• The SSR branches supply sensation to the skin on the dorsum of the thumb and back of the hand.

Posterior Approach to the Radial Nerve

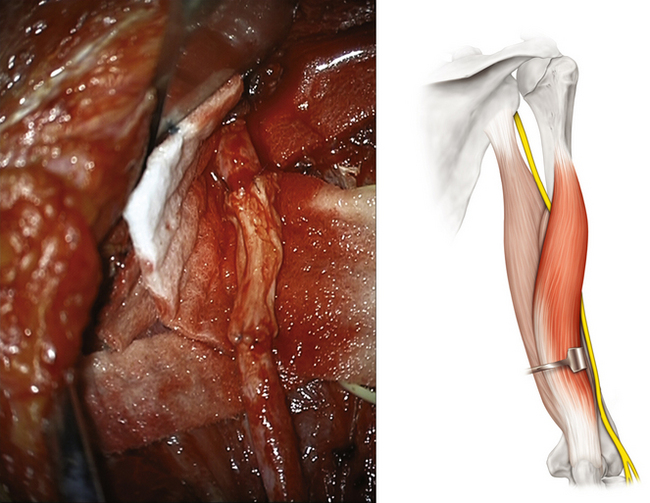

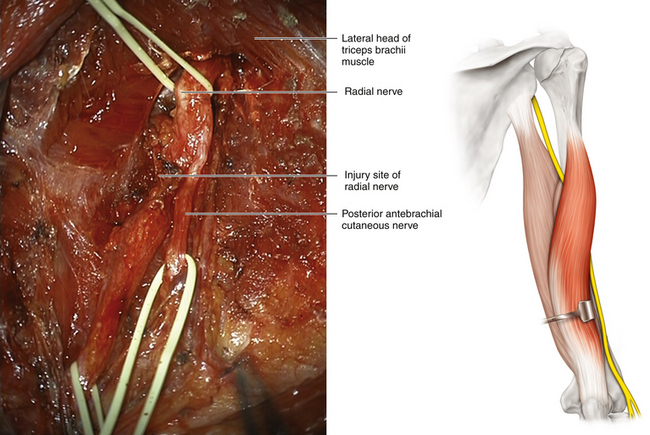

• There are times when it is advantageous to expose the arm-level radial nerve from a posterior approach.

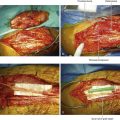

• The disadvantage of this approach is that access to the proximal and distal radial nerve is limited; therefore, the surgeon should be certain as to the exact site of nerve injury and that it can be appropriately exposed from behind, primarily in its course behind the humerus but also when the nerve is lateral to the bone (Figures 10-20 and 10-21). An understanding of the posterior view of the shoulder and humerus is necessary for this approach.

• The junction of the lateral and long heads of the triceps posteriorly is an important landmark for the posterior approach to the radial nerve. By splitting these two heads, the nerve is seen in its direct relationship with the posterior aspect of the humerus. As the plane between the long and lateral heads is widened, the radial nerve is seen posterior to the humerus.

• The nerve is seen at first between the long and medial heads of the triceps and later between the lateral and medial heads of the triceps.

Figure 10-20 The proximal and distal nerve have been dissected on either side of a focal radial nerve injury.

Skin Incision

• The skin incision should be centered between two of the triceps heads. The incision usually begins at the lower and posterior border of the deltoid and extends down the middle of the posterior aspect of the arm and toward the olecranon process.

• This incision provides some exposure of the radial nerve proximal to, through, and below the spiral groove (Figure 10-22).

• The incision is deepened between the triceps muscle masses, and their intermuscular septum is divided to expose the radial nerve at a deeper level. A retractor is helpful in displacing the deltoid muscle proximally.

• Proximally, triceps branches can be seen leaving the nerve before it enters the region of the spiral groove.