Chapter 60 Rabies

Rabies has terrorized humanity since the dawn of civilization, and the menace continues. In industrialized nations where human rabies is rare, animal rabies abounds and humans are protected from infection only by vigorous animal vaccination programs, elimination of stray animals, and postexposure immunization. In developing countries, tens of thousands die each year, and over ten million endure agonizing anxiety following exposure to a possibly rabid animal.217 In the United States, approximately 23,000 persons receive postexposure prophylaxis each year.70,179 An encounter with this uniformly fatal infection, globally the most common form of viral encephalitis, leaves “a more indelible stamp of horror” than does any other disease.138

Current Status

Globally, rabies is the tenth most frequent cause of death from infectious disease.106 The actual number of deaths is unknown because reporting in the developing countries where this infection is common is unreliable. In Tanzania, the estimated incidence of human rabies mortality was 1499 a year (95% confidence interval 891 to 2238), but the average number of deaths officially recorded was 10.8.73 Most of these countries do not have laboratory facilities capable of establishing a dependable diagnosis.68 The World Health Organization (WHO) currently estimates the number of rabies deaths globally at 40,000 to 70,000 a year, although the median number of 55,000 deaths is widely accepted. That is an average of approximately one death every ten minutes.221

Some, perhaps many, human rabies infections are not diagnosed, even in nations with sophisticated medical systems. This problem was vividly dramatized in 2004 by the rabies deaths of four U.S. organ transplant recipients from a donor whose rabies infection had not been recognized.59,64 Only a few months later, three organ transplant recipients in Germany died of rabies and three others with liver and corneal transplants required postexposure prophylaxis.119 A review has suggested that rabies may be underdiagnosed in the United States because physicians see it so infrequently they do not include it in their differential diagnoses.217

In addition to being undiagnosed, rabies is probably incorrectly diagnosed with considerable frequency. Of 33,000 human rabies deaths reported worldwide in 1997, laboratory confirmation was available for less than 0.5%.68

The Rabies Virus

Rabies viruses belong to the group Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus. Seven genotypes are recognized, but genotype 1 is the only one of major significance. This genotype consists of multiple variants or lineages, each closely linked to a single mammal species such as raccoons, skunks, foxes, mongooses, or various bat species. In the 1980s these variants were distinguished with monoclonal antibodies. Subsequently, analysis of nucleotide substitutions in the rabies genome after reverse transcriptase—polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification of the viral RNA has allowed identification of the primary reservoirs for each variant, mapping the geographic distribution of variants, and identification of virus spillover into animals and humans.68,191 In addition, for the past 30 years, the source of many human infections has been identifiable in the absence of a recognizable exposure to rabid animals.

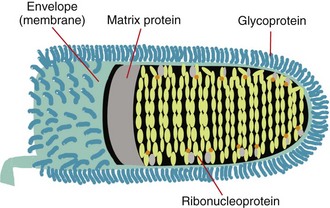

The rabies virus is bullet-shaped with one flat end and contains a single strand of RNA, which is made up of approximately 12,000 nucleotides and encodes five proteins. Three of these, the nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P, M1, or NS), and the large polymerase or transcriptase protein (L), make up the core of the virus. The other two, the matrix protein (M) and the transmembrane glycoprotein (G), form its coat.230

The external surface is studded with perpendicular aggregates of glycoprotein, the G protein that recognizes cell surface receptors and facilitates virus entry into cells.15 The 505-amino-acid G protein is composed of a 44-amino-acid internal or “cytoplasmic” portion, a 22-amino-acid hydrophobic transmembrane portion, and the large external “antigenic” portion.160,231 The complete amino acid sequences of these proteins have been determined for several fixed rabies strains.219

A lipid bilayer is closely associated with the matrix protein, and the two form a clearly defined shell for the virus. The M protein is the smallest of the rabies virus structural proteins, with only 202 amino acids,232 but makes up approximately 25% of the total virion protein. It is in close contact with the core and also interacts with the internal segment (cytoplasmic tail) of the surface G protein.

The core of the virus forms a tightly structured helix of 30 to 35 coils that extends end-to-end within the virion. The RNA genome is associated with about 1800 closely packed molecules of the 55 kDa nucleoprotein, which together are known as ribonucleoprotein (RNP). The N protein protects the genome from digestion and keeps it in a suitable configuration for transcription. Some 30 to 60 copies of the large (≈190 kDa) transcriptase-associated L protein and about 950 copies of the smaller (≈38 kDa) P or phosphoprotein are responsible for replication of the viral RNA232 (Figure 60-1).

Rabies in the United States

Incidence in Humans

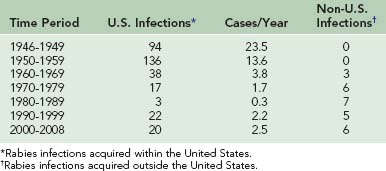

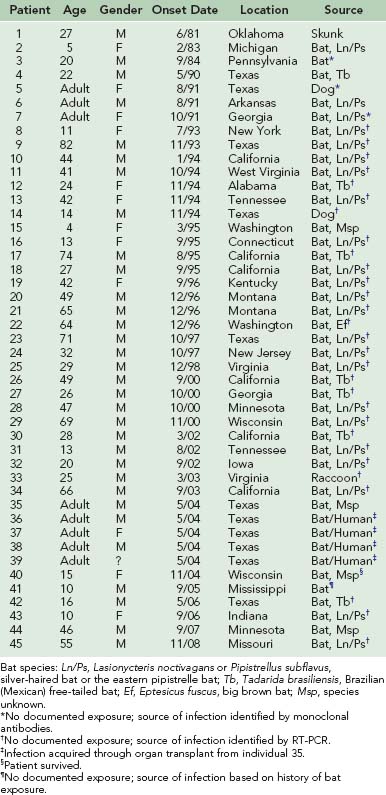

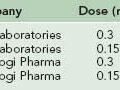

The incidence of human rabies in the United States fell dramatically from 23.5 infections per year in the late 1940s to 1.0 infection per year during the 1980s (Table 60-1). However, 27 infections were reported from 1990 through 1999, and 26 have been reported from 2000 to 2002. From 1980 to 1989, seven infections were acquired outside the United States. From 1990 to 1999, five infections were acquired outside the United States, and from 2000 to 2008, six infections were acquired in other countries.* Of the human rabies infections acquired in the United States, one originated from a skunk (1981) and two originated from dogs (1991 and 1994). The two dog infections were associated with the epizootic in coyotes that developed when rabies spread across the Rio Grande River from unvaccinated dogs in Mexico. The remaining 42 infections originated from bats. Of the 18 human rabies infections acquired outside the United States during these 28 years, 17 originated from dogs. Only an infection in 2008 in California was determined to have originated from a Mexican free-tailed bat34 (Table 60-2).

TABLE 60-2 Rabies Deaths in the United States Since 1980 From Infections Contracted Outside the Country

Although reliable rabies vaccines and antisera first became available during this 62-year period, extensive vaccination of domestic animals, particularly household pets, and elimination of unrestrained and stray animals are considered primarily responsible for the decline in the human infection rate.53,54,151 Such programs reduced the incidence of laboratory-confirmed rabies in dogs from 6949 in 1947 to 75 in 2008.30 The annual cost for these programs is over $300 million, most of which is borne by pet owners.192

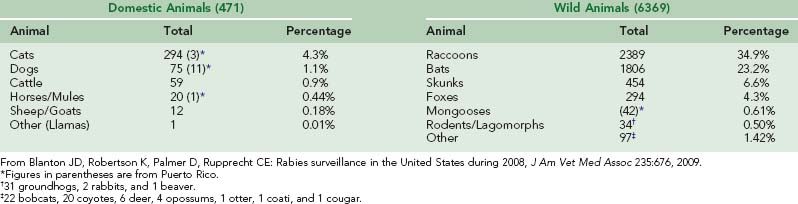

Rabies in Wild Terrestrial Animals

In the United States and Canada, a vast reservoir of rabies persists in wild animals.192 During 2008, 49 states and Puerto Rico reported 6841 rabies infections in animals, approximately 93% in wild animals and 7% in domestic animals. However, some states accept only animals responsible for a human or domestic animal incident for rabies testing; others test all submitted specimens. Furthermore, the number of rabid wild animals that die without being detected is estimated to be more than 90% of the total, so the identified infections represent only a small fraction of wild animal rabies.125

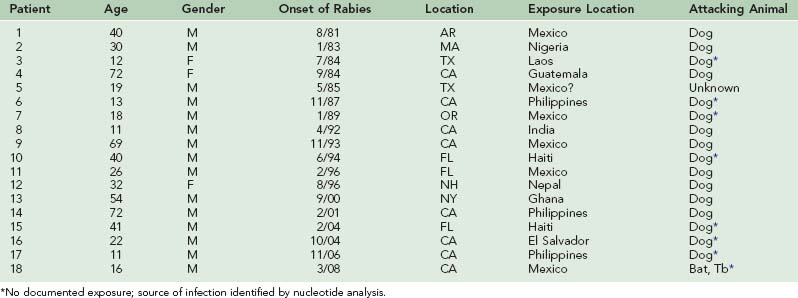

Several major rabies epizootics are currently recognized. An epizootic of rabies started in Arctic foxes in northern Canada in the late 1940s and early 1950s and swept southward in the middle and late 1950s to involve red foxes in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. The epizootic crossed the St Lawrence River in 1961, where it involved red foxes in upper New York State, although currently it appears to be limited to the adjacent Canadian provinces, which are experiencing a lower incidence of fox rabies.11,28,127 The epizootic, which moved westward to involve arctic foxes in Alaska and the Northwest Territories,190 surrounds the North Pole and may cover the largest land area of any observed outbreak28 (Figure 60-2).

FIGURE 60-2 Rabid foxes reported in the United States in 2008.

(http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/resources/publications/2008-surveillance/foxes.html.)

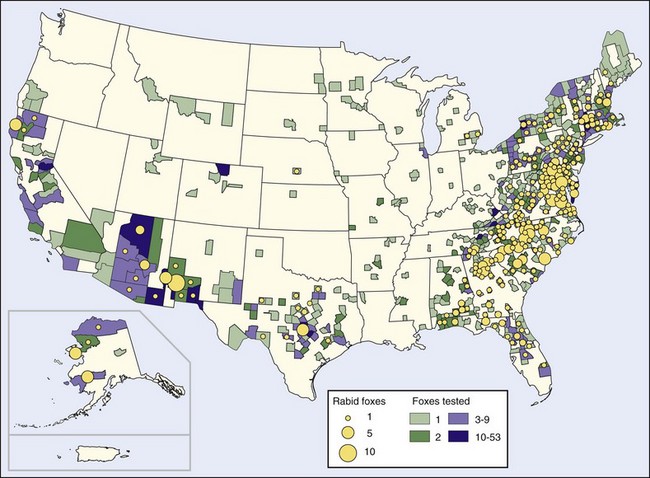

An outbreak of raccoon rabies started in central Florida in the 1940s and spread at the rate of about 40 km (25 miles) per year, reaching Georgia in the early 1960s and Alabama and South Carolina in the 1970s. In the late 1970s a second outbreak appeared on the Virginia–West Virginia border. That epizootic has now spread north to all of New England; in 1999 it crossed into Canada. It has also spread south to join with the epizootic coming north from Florida in North Carolina.46,68,69 The second outbreak developed when raccoons were translocated from Florida for restocking for hunters. Although the animal suppliers held legal permits and health certificates, inclusion of some rabid animals among the more than 3500 transported raccoons has been documented.118,229

As of 2002 more than 50,000 rabies infections in raccoons had been reported in the United States since 1975. The land mass affected by this epidemic is approximately 1 million km2 (383,000 miles2) and includes the residences of 35% of the United States human population (Figure 60-3). The raccoon epizootic is considered particularly threatening because many raccoons live in densely populated urban and suburban areas.68 However, the only known human rabies infection resulting from this epizootic occurred in 2003.47 The spread of rabies from raccoons to humans appears to have been limited in part because raccoons are large animals and their bites are obvious. To some extent, well-vaccinated dogs and other pets form a barrier between wild animals and humans. Perhaps of greatest significance is the nonaggressive behavior of rabid raccoons. In 38 rabid raccoon incidents in Florida over a 5-year period, bites were inflicted only when humans or dogs tried to kill or capture raccoons that seemed tame.226

FIGURE 60-3 Rabid raccoons reported in the United States in 2008.

(http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/resources/publications/2008-surveillance/raccoons.html.)

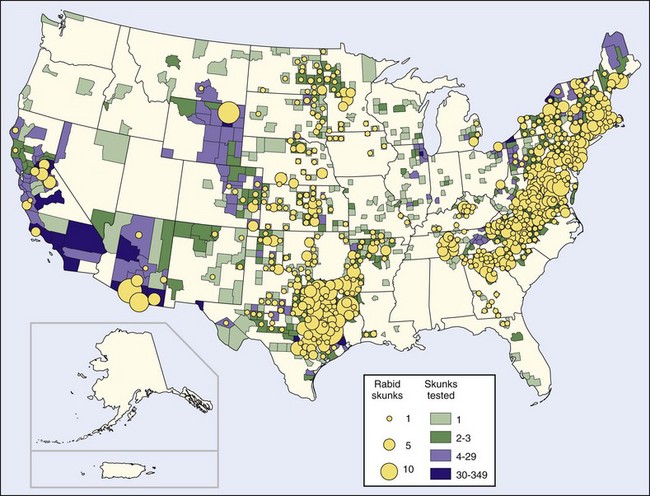

Before the raccoon epizootic, most terrestrial rabies in the United States was in skunks. Human rabies resulting from exposure to a spotted skunk in California was reported in 1826.67 Four epizootics are recognized, one of which is in the province of Quebec, Canada, and New York state and is associated with the fox epizootic in that area. A larger epizootic started in Iowa in 1955. It has spread east to Ohio, west to Montana, north to the Canadian provinces of Manitoba (1959), Saskatchewan (1963), and Alberta (1971), and south to meet with a third epizootic that originated in Texas and has spread to surrounding South Central states, particularly Oklahoma and Arkansas. The fourth epizootic in skunks is located in northern California67 (Figure 60-4).

FIGURE 60-4 Rabid skunks reported in the United States in 2008.

(http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/resources/publications/2008-surveillance/skunks.html.)

An increase in the number of rabid skunks in the East Coast states has recently occurred, but analysis of these infections indicates they result from raccoon rabies spilling over into skunks and are not indicative of a separate skunk epizootic.103

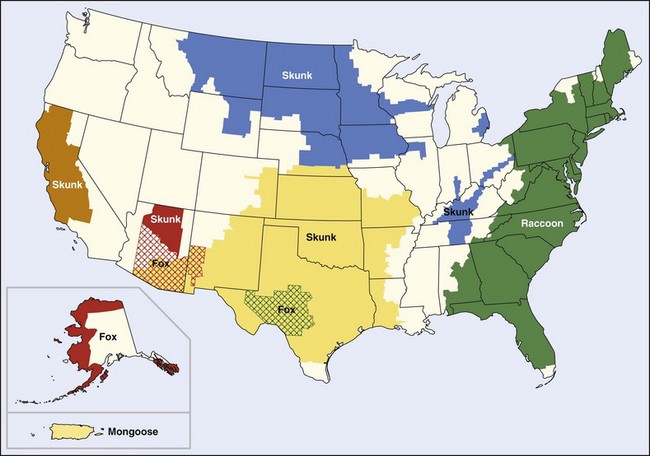

Screening of rabies virus isolates from the epizootics has disclosed five distinctive patterns. Red foxes and skunks in New York and adjacent Canada present one pattern; raccoons from the Atlantic states present a second. The skunks in the south-central states present a third, and a fourth is represented only by a small outbreak in gray foxes in Arizona. However, the fifth pattern is found in skunks from the north-central states and from California, in dogs from the Mexico border states, and in a small rabies outbreak in gray foxes in Central Texas189 (Figure 60-5).

FIGURE 60-5 Terrestrial rabies reservoirs in the United States in 2008.

(http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/location/usa/surveillance/wild_animals.html.)

Rabies in rodents is an intriguing problem. Rodents are the animals of choice for rabies virus isolation in the laboratory; yet rabies in small free-living rodents is rare. One explanation is that rodents may usually be killed rather than simply infected by the bites of rabid animals, but rodents are carrion eaters and can be infected by that source as well. In recent years the largest number of rodent rabies infections has been in large rodents such as woodchucks that have been infected by rabid raccoons. Rabid beavers have attacked and bitten humans in North Carolina. However, no transmission of rabies to humans by rodents has been documented.200

Rabies in Bats

With the exception of Antarctica, rabies in bats is global. In Canada, the United States, parts of South America, Western Europe, and Australia (where rabies in carnivores, particularly dogs and foxes, has been controlled), bats are the most prominent source of human rabies.148

Rabies was diagnosed in insectivorous bats in Brazil in the 1920s and in frugivorous bats in Trinidad during the 1930s, although the principal subject of these studies was rabies in hematophagous (“vampire”) bats that was being transmitted to humans. The first definitive diagnosis of rabies in nonhematophagous bats was made in a frugivorous bat that flew into a “chemist’s” shop in Port of Spain, Trinidad, on September 10, 1931. However, the incident that drew widespread attention to bat rabies occurred in Tampa, Florida, on June 23, 1953. The 7-year-old son of a ranch hand was looking for a baseball near some shrubbery when a lactating female yellow bat suddenly flew out of the bushes and bit the boy on the chest, remaining firmly attached until knocked off by the boy’s mother. The ranch owner had heard of rabies in vampire bats in Mexico and insisted the bat be examined for infection. Negri bodies were found in smears of the brain, and the diagnosis was confirmed by mouse inoculation of brain tissue. The boy was given postexposure treatment and did not develop an infection.17,69,219

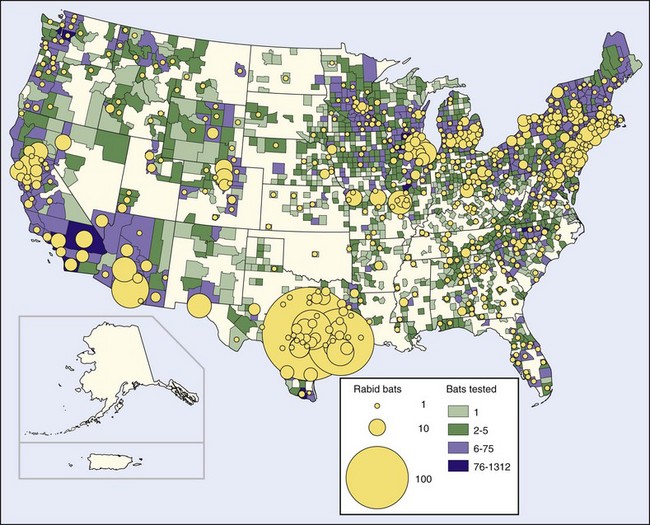

The publicity given this event led to many more bats being submitted for rabies examination. Subsequently, rabies has been found in bats in every state except Hawaii, as well as in eight Canadian provinces.17,165 In 2008, bat rabies was reported from all 48 of the continental states and the District of Columbia54 (Figure 60-6). The estimated incidence of rabies in bats in the United States is 0.5% to 1.0%; the incidence in bats that appear ill or injured is much higher, 7% to 50%.17,201

FIGURE 60-6 Rabid bats reported in the United States in 2008.

(http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/resources/publications/2008-surveillance/bats.html.)

Rabies virus variants from bats are species specific rather than geographically specific189 and are distinctly different from those of terrestrial animals in the same locations, including the major terrestrial epizootics. Clearly, little exchange of infection between bats and terrestrial animals takes place, although occasional animals infected with rabies virus strains typical of bats are found. Many large areas of the United States, particularly the Pacific Northwest and New England (prior to the raccoon epizootic), report rabies in bats but in no other species. Even though cats and foxes catch and eat bats, only 3 of 136 cat and fox rabies isolates over a 2-year period were antigenically similar to bat rabies strains.17,79,189

Approximately 70% of human rabies infections and 75% of cryptic rabies deaths in the United States have been caused by the variant associated with silver-haired and the eastern pipistrelle bats, which are reclusive animals rarely found around human habitation. Infections by variants associated with bats that frequent human dwellings are much less common. Infections in other animals by this variant are also disproportionately very high. These bats are small and their bites are difficult to detect. However, in comparison with other rabies virus variants, the variant associated with these two bats replicates better in fibroblasts and epithelial cells, and replicates better at the low temperature of 34° C (93.2° F). These features indicate this variant is better able to replicate in the peripheral tissues involved by most bites.140

Rabies in Domestic Animals

Since rabies in dogs has been controlled, rabies infections in cats have outnumbered infections in dogs (295 to 75 in 2008).30 A major problem in vaccinating cats is establishing ownership. Farmers value cats for rodent control but do not recognize them as property. Cats wander from farm to farm and contact wild animals with rabies. Capturing feral cats so they can be vaccinated is difficult.42 Rabies is not rare in other domestic animals, including cattle, horses, mules, sheep, and goats (Table 60-4).

Sources of Human Infection

In the late 1940s and 1950s most human rabies in the United States resulted from bites by dogs or cats. Of 146 infections in the years 1946 to 1961 for which a source of exposure could be identified, dogs were responsible for 120 and cats for 9 (88.4%). Foxes (7), skunks (5), and bats (5) were responsible for the rest.53 However, after rabies in domestic animals was controlled, human rabies resulting from bites by pets disappeared. Since 1966, all but 2 of the 19 human rabies infections resulting from exposures to rabid dogs were acquired outside of the United States.53,62,151

Before 1965, the CDC had recorded no human rabies occurring within the United States that had been acquired outside the country.151 However, since then the number of infections acquired outside the United States has been significant: 3 of 15 (20%) between 1965 and 1970, 6 of 23 (26%) in the 1970s, 7 of 10 (70%) in the 1980s, and 18 of the 63 cases (29%) since 1980. Lack of knowledge about the risk for rabies in developing countries has led some travelers to disregard animal encounters and not obtain rabies immunoprophylaxis, but some of these infections have been in children who did not inform their parents of the animal contact.

Until the 1980s, identifying the source of a number of human rabies infections in the United States was impossible. For many infected persons no animal exposure incident—even an opportunity for animal exposure—could be identified. An infectious source could not be found for 84 of 230 (35%) human rabies infections occurring in the United States between 1946 and 1961,151 or for 6 of 38 (16%) human infections between 1960 and 1970.52

Only since the 1980s has monoclonal antibody typing or RT-PCR nucleotide analysis allowed the source of human rabies infections to be determined when no animal exposure incident could be identified.17,79,189 However, such studies have made it unmistakably clear that bats are now the major source of human rabies in the United States.

Of the 45 human rabies infections acquired within the United States since 1980, 42 are attributed to bats. A study of human rabies of bat origin in the United States and Canada from 1950 through 2007 identified 56 infections, of which 22 (39%) reported a bite, 9 (16%) had a direct contact but no bite, 6 (11%) found one or more bats in their homes (two in the room in which they slept), and 19 (34%) had no history of a bat contact.76

How the infection is transmitted has been uncertain. In 1956 and 1959, two men died of rabies after exploring Frio Cave near Uvalde, Texas. The walls and ceiling of that cave hold astonishing numbers of bats—300 to 400 per square foot. Neither man had been bitten, and the infections were attributed to aerosol transmission of the rabies virus. Subsequently, when experimental animals of various species were placed in the cave in cages that only allowed the virus to be transmitted as an aerosol, a significant percentage developed rabies.74,75 Additionally, aerosol transmission of rabies to humans has occurred at least twice in laboratories.24,228 The CDC recommends rabies vaccination for spelunkers.56

However, nursery caves such as Frio Cave contain an astounding number of bats. Saliva and urine constantly rain down on anyone entering the cave, and the blanket of guano on the floor ranges from several inches to several feet in thickness. In Frio Cave air circulation is so poor that the bats warm the cave, the air is humidified by their respiration, and the concentration of ammonia from their urine is so high that the cave usually cannot be entered without respirators.74 Similar infections in other caves have not been reported.

Unrecognized bites appear to be the source of infection for most individuals who have had no recognized bat encounters. Bat teeth are so small and sharp that a bite may not be felt. Even the recognized bites are not particularly painful, although at least one of the individuals known to have been bitten was intoxicated with ethanol at the time.98 For centuries, South American vampire bats have been reported to bite sleeping victims without awakening them.

Limiting human rabies of bat origin is best addressed by informing the public of the risk.165 Reducing the bat population is not an acceptable approach. Significant population reduction would be difficult and, if achieved, would be an ecologic disaster because bats play such a major role in insect control (Table 60-3).

The CDC and other institutions now advocate the following measures:

Rabies in Other Countries

Epidemiology

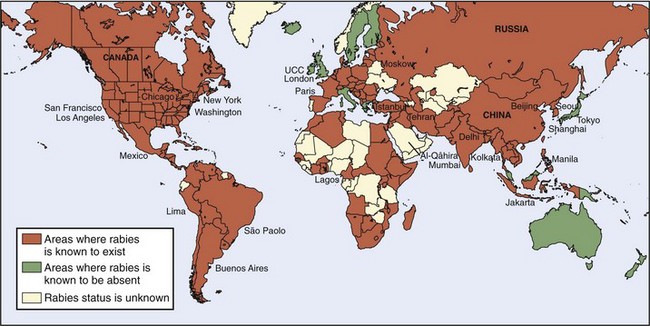

Rabies is found throughout the world, and although more common in tropical or temperate climates, is by no means limited to those areas. Arctic foxes with rabies have been found in Alaska, Northern Canada, Greenland, Norway’s Svalbard Islands, and much of Siberia. An epizootic in the Thule district of Greenland in 1958 and 1959 resulted in death from rabies of 50% of the sled dogs in that area. More than 1000 dogs in the Egedesminde district died in another epizootic in 1959 and 1960. For reasons that are not known, transmission of rabies to humans is rare in these areas, even though exposures are common.75 Perhaps the rabies variant is more infective for foxes and dogs.

Rabies is not found in a few areas of the world, all of which are landmasses or peninsulas isolated by water. Rabies does not occur in Hawaii (the only state in the United States in which rabies is not found), some of the Caribbean islands, Pacific Oceania (including Australia [although Australian bat lyssavirus is found there] and New Zealand), or Antartica.101,147 The two human genotype 1 rabies infections that have occurred in Australia are thought to have been acquired outside that country24,58,101 (Figure 60-7).

(Modified from http://www.nathnac.org/pro/factsjeets/rabies.htm, and http://www.ktl.fi/portal/sip,o/julkaisut/oppaat_ja_kirjat/matkailijan_terveysopas_old/4_matkailijoiden_rokotukset/1415.)

Great Britain had been free of rabies since an extensive dog confinement and vaccination program in 1903, although concern about reintroduction of rabies was raised by the Channel Tunnel and the reduction of border controls between members of the European Community.69,202 A 55-year-old Scotsman with a fatal infection in 2002 was the first locally acquired lyssavirus infection on that island in 100 years, but the virus was not of genotype 1.94

Rabies has been endemic in Japan since the 10th century. However, following World War II, members of the U.S. Army Veterinary Corps determined that no reservoir of rabies existed in the wild animal populations of Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines—perhaps in part because wild animals were hunted for food during the war. Extensive campaigns to eliminate stray dogs (which in some areas of Japan reduced the canine population by 70% to 80%) and to vaccinate those remaining succeeded in eradicating the infection from Japan and Taiwan. Endogenously acquired rabies has not occurred in those islands since the late 1950s.5,191

The success of canine rabies eradication programs depends on the society in which the programs are initiated. Such programs achieve little success in nations that are predominantly Hindu or Buddhist, because the people do not support elimination of animals that have no apparent owner. They often put out food for stray dogs. In contrast, Malaysia, a peninsula that is predominantly Muslim, has been largely free of rabies since the early 1950s.25

Elimination of stray dogs must be combined with vaccination programs. Dogs that are eliminated because they cannot be associated with human ownership are quickly replaced. The annual turnover of the dog population in developing countries has been found to range between 30% and 40%.31

Vaccination of domestic animals for rabies is limited largely to industrialized nations. In many developing countries, vaccination of animals is considered unaffordable and rabies control resources are expended on postexposure immunoprophylaxis of humans. Even though rabies immunoprophylaxis is administered to 800 to 900 persons per million inhabitants annually in such countries, the human death rate from rabies is still high, an average of nearly five deaths for each 1 million population annually.32 In the United States that death rate would result in approximately 1500 rabies deaths a year.

In the 1990s the Institute’s postexposure rabies clinic treated about 18,000 patients with new animal bites each year—an average of almost 50 new patients a day! Furthermore, these patients were only 28% of the estimated 64,000 Thais who receive postexposure therapy annually, many of whom were residents of rural or remote portions of the country and were treated by local physicians.224 However, the number of human deaths from rabies in Thailand declined from about 400 a year in the 1970s to 70 in 1999, even though dog rabies has not been controlled.68

Other developing nations have similar rabies problems. WHO agencies have estimated that 87 countries and territories with a total population of about 2.4 billion people are afflicted with endemic canine rabies.32

Sources of Human Infection

Although domestic animals are rarely the sources of human rabies in the United States and other developed countries, in developing countries the vast majority of human rabies—99% by some estimates—is the result of exposure to rabid dogs.33,69,213,219 In Thailand, although rabies has been found in an array of exotic tropical animals, including tigers and leopards, between 1979 and 1985, 90.6% of human infections resulted from dog bites and an additional 6% followed unknown events. The remaining 3.6% followed cat attacks.181

Other animals, particularly bats, transmit rabies. Hematophagous, or “vampire,” bats are a major source of animal and human rabies in South and Central America, the only areas where such bats are found. Their range extends between northern Mexico and northern Argentina—basically between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn—and fossils indicate vampire bats have inhabited those areas for 2.5 million years.93 These animals consume 20 to 25 mL of blood at a feeding, and although cattle are their preferred food source, a study in Colima, Mexico, found human blood in the stomachs of 15.7% of 70 vampire bats.13

Human rabies of vampire bat origin was first recognized in 1929 in Trinidad when Negri bodies were found in the brains of 17 individuals, mostly school-age children, who died with acute ascending paralysis. Subsequently, small epidemics have been recognized almost every year in that country. Interestingly, almost all of the rabies transmitted by vampire bats in Latin America is paralytic in type rather than furious.215

Human rabies resulting from vampire bat bites has been reported almost every year from Mexico, but was first reported from South America in 1953 when 9 of 43 diamond miners who slept outdoors died of a mysterious illness. Autopsies of five of the miners disclosed rabies. In an outbreak in two rural communities in the Amazon Jungle of Peru during the first four months of 1990, 29 of 636 residents (4.6%) died after a rapidly progressive illness characterized by hydrophobia, fever, and headache. Rabies virus was isolated from the brain of the only individual on whom necropsy was possible. Of the 29 victims, 96% had a history of bat bites, although bats also had bitten 22% of unaffected community members.6

Human infection is not the only major problem resulting from rabies transmitted by vampire bats in Central and South America. Migrating epizootics of vampire-bat–transmitted bovine paralytic rabies kill thousands of animals annually; the estimated cost in 1980 was $500 million.6,68 Efforts to control these epizootics have included vaccination of cattle and attempts to limit the vampire bat population by administering anticoagulants, usually warfarin.

It is interesting to note that meat is often consumed from cattle slaughtered at the first, virtually pathognomic sign of disease, paralysis of the hindquarters. Even normal appearing animals may have infected brains. Four of 1000 (0.4%) apparently healthy cattle selected at random at the Mexico City slaughterhouse of Ferrería were found to be infected by rabies when investigated with fluorescent antibody staining and animal inoculation of brain tissue. However, no cases of human rabies from this source have been reported.13 Human rabies has resulted from consumption of brain tissue from a rabid dog and a rabid cat in Vietnam.218

Mongooses are the major source of rabies in South Africa and in some Caribbean Islands such as Puerto Rico.14,88 The yellow mongoose is the main reservoir of rabies in South Africa.219 The small Indian mongoose, imported many years ago in an effort to control rodents,107 is an important reservoir and vector of rabies in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Grenada, Haiti, and Puerto Rico.219 In Grenada, from 1968 to 1984, mongooses accounted for 787 (73%) of 1078 cases of animal rabies on the island. Of 208 human exposures requiring antirabies therapy, mongooses were responsible for 119 (57%). The possibility of eliminating the animals by hunting or trapping appears remote in view of the island’s topography and the animal’s skill at adapting to its surroundings. However, mongooses take oral baits, so oral vaccination appears feasible if an appropriate vaccine can be identified.133 About 20% to 40% of mongooses have naturally acquired antirabies antibodies, possibly from having survived infection.82

At the Canadian International Water and Energy Consultants (CIWEC) Clinic in Kathmandu, Nepal, 51 travelers required immunoprophylaxis following rabies exposure during a 2-year period. Although 36 of these encounters were with dogs, 10 were with monkeys at Swayambhunath, the “Monkey Temple,” a Buddhist shrine popular with tourists. The bites were inflicted when monkeys leaped for food carried by visitors.185

Human-to-human transmission of rabies is rare. Eight documented infections were in individuals who received corneal transplants (two from the same person) from individuals whose neuroparalytic disorder was not recognized as rabies.57,92,111 In 1996, Fekadu and colleagues reported two apparent instances of human-to-human rabies transmission in Ethiopia. A 41-year-old woman, who died of rabies 33 days after her 5-year-old son died of the same infection, had been bitten on a finger by her son. Another 5-year-old boy, who developed rabies 33 days after his mother died of that infection, had been repeatedly kissed on his mouth by his mother, apparently passing infected saliva to him. However, these infections were not confirmed by laboratory studies.90

The donor’s lungs were transplanted to a male who died of intraoperative complications. The liver and one kidney were transplanted to males, and one kidney was transplanted to a female, all of whom died of rabies 27, 37, and 39 days later. The fourth victim had a liver transplant from another donor, but a segment of iliac artery from the first (rabid) donor was inserted during the procedure. This recipient died of rabies approximately one month after the transplant.59,64

In the same year, three German individuals who had received a lung, a kidney, and a kidney/pancreas transplant from the same individual died of rabies. When the cause of their deaths was recognized, three additional transplant recipients who had received a liver and two corneas were given postexposure prophylaxis and survived. The corneas were removed. The donor had been scratched by a dog while visiting India and had not received postexposure therapy. The nature of her disease was not recognized until the three transplant recipients died.119

One case of human rabies appears attributable to transplacental infection. However, a number of mothers dying of rabies encephalitis have given birth to healthy babies, presumably because the virus travels through nerves—viremia has never been documented—and cannot reach the placenta or fetus.91,111

Features of Human Rabies

Mortality

Rabies in humans, once it has become clinically apparent, is uniformly fatal. No other infection is so lethal or progresses so rapidly. In the 1970s intensive support allowed three humans with clinical rabies to survive.61,105,159 Three rabies survivors have been reported subsequently. The first five infections were vaccination failures, and four of the five survivors had severe residual neurologic deficits, severe enough to be fatal 34 months later in one person.2,136 The rabies virus was not cultured from any of these patients and at least one may have had a reaction to neural-derived vaccine rather than an actual infection.117

Coma was induced with ketamine and midazolam, she was intubated and maintained on a ventilator, and received intravenous ribavirin and amantadine. Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic, but it is also an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist, and the NMDA receptor has been speculated to be one of the rabies virus receptors. Later she also was given benzodiazepines and supplemental barbiturates. She recovered slowly, was removed from isolation on the 31st day, and was discharged from the hospital on the 76th day. Attempts to isolate the rabies virus, detect viral antigens, or identify rabies RNA in two skin biopsies and nine salivary specimens were uniformly unsuccessful. Five months after her initial hospitalization, she was alert and communicative, but had choreoathetosis, dysarthria, and an unsteady gait. Twenty-five months after hospitalization, she continued to have fluctuating dysarthria and gait difficulties, as well as an intermittent sensation of cold feet. She had no difficulties with activities of daily living, including driving. In high school, she took college-level courses in English, physics, and calculus, scored above average on a national college achievement test, graduated in 2007, and planned to attend a local college. She had no problems with peer relations or mood disorders.62,113,227

At the time, hope was held that this therapy might be a breakthrough in the treatment of clinical rabies. However, a number of individuals have subsequently been treated by the same protocol, and none survived.29,110,136

Testing for evidence of 30 other causative agents of encephalitis or aseptic meningitis was uniformly negative. Her illness has been classified as presumptive abortive human rabies.60 Other than the 15-year-old girl from Wisconsin and the 17-year-old from Texas who received only a single dose of vaccine, no person who has not been vaccinated has survived clinically evident rabies. (Subclinical human infections probably occur, as discussed later.) The clinical phase of rabies encephalitis rarely lasts more than a few days to a few weeks, and infected persons are severely incapacitated.3,92 The catastrophe of rabies is compounded by the young ages of many of its victims; 40% to 50% are 15 years old or younger.92

Incubation Period

For many years, some human rabies infections have been thought to follow prolonged incubation periods. In 1987, a 13-year-old boy who had immigrated from the Philippine Islands 6 years earlier died with rabies determined by nucleotide analysis to be of Philippine dog origin. He had not been out of the United States since he arrived.49 The second documented Australian rabies patient, a 10-year-old girl of Vietnamese origin, had experienced no identifiable animal contact since she had left North Vietnam 6 years and 4 months earlier. She had spent some time in Hong Kong, and the virus responsible for her death was of an immunotype found in China, although the brain tissue was partially decomposed and nucleotide sequencing was limited.24,101,120 Joshi and Regmi have reported an individual who had an apparent incubation period of 1100 days (3 years).123 The first documented patient with rabies reported in Australia, a 10-year-old boy who died in 1987, probably resulted from a monkey bite inflicted in northern India 16 months earlier.58 An 18-year-old Mexican man who died in Oregon in 1989 was infected with rabies virus of a strain to which he could not have been exposed for at least 10 months, although no history of any type of exposure could be obtained.52 Even longer incubation periods of 10 years and  years have been reported, but these occurred in areas where rabies is endemic and a second exposure in the intervening period could not be ruled out.189

years have been reported, but these occurred in areas where rabies is endemic and a second exposure in the intervening period could not be ruled out.189

Confirmation of such prolonged incubation periods was achieved in three immigrants into the United States from the Philippines, Laos, and Mexico. Nucleotide analysis disclosed rabies viral amino acid compositions essentially identical to the patterns from rabies viruses isolated from dogs in their native countries and unlike rabies viruses found in the United States. These individuals had been in the United States for 6 years, 4 years, and 11 months before the onset of clinical disease.189,192

In 2004, a 22-year-old man from El Salvador who had been in Los Angeles for 15 months died of rabies that, by nucleotide analysis, was typical of rabies viruses found in dogs in El Salvador and unlike viruses found in the United States.126

Almost 99% of human rabies infections clinically manifest in less than 1 year, typically 2 to 12 weeks.15,24,92 The median incubation period in the United States for persons diagnosed between 1960 and 1990 was 24 days for those 15 years old and younger, but 43.5 days in people older than 15. Fixed (laboratory) strains of virus tend to produce shorter incubation periods than do wild or “street” strains. In 1960 in Brazil, 60 people were injected with vaccine that had been inadequately inactivated. Sixteen developed rabies, and the incubation periods ranged from 4 to 16 days.92

The size of the viral inoculum clearly influences the incubation period. Experimental animals injected with large numbers of viruses develop clinical infections significantly faster than do those receiving small inocula. Small inocula resulted in greater central nervous system histologic damage and more widespread infection outside the central nervous system, particularly in salivary glands.87

Pathogenesis of Central Nervous System Infection

Immediately after a bite (or investigational injection), rabies virus can be identified at the site with fluorescent antibodies and remains near the wound or injection site for hours to weeks, depending on the animal species. Viral antigen can be demonstrated in muscle, and viral particles budding into the sarcoplasmic reticulum and from the sarcolemma have been demonstrated by electron microscopy.67 The virus appears to enter both motor and sensory nerves, probably through motor endplates and neuromuscular spindles.12,177

Passage of the virus through peripheral nerves was demonstrated in 1887 when rats80 and rabbits81 were protected from rabies following injections of the virus in their hind legs by sectioning the sciatic nerve. After entry into peripheral nerves, the virus travels at a rate of about 5 to 10 mm per hour to neuronal cell bodies such as dorsal root ganglia.15,67 Replication can begin at this site, and prolonged ensconcement at this site has been suggested as one explanation for prolonged incubation periods.177

Upon reaching the CNS, the virus is widely disseminated with extreme rapidity, almost simultaneously with entry, but the manner in which the virus disseminates throughout the CNS is not known. Viremia has not been documented. Plasma membrane budding from infected to uninfected neurons and dissemination through intercellular spaces or cerebrospinal fluid have been suggested. Clusters of viral particles at neuromuscular junctions, reduction of viral infectivity by nicotinic acetylcholine receptor competitors, and other data suggest that the virus recognizes cholinergic binding sites and perhaps enters peripheral and central nerve fibers through those sites. The large numbers of muscle cholinergic binding sites in foxes, which are exquisitely sensitive to rabies, and the small number of such sites in opossums, which are highly resistant to rabies, support this hypothesis and possibly explain the mechanism of sensitivity or resistance.15 The glycoprotein that coats the viral particle is a major determinant of neuroinvasiveness, and alteration of this protein can markedly alter the kinetics of CNS viral spread.12

Viruses can be isolated from cerebrospinal fluid—a significant antibody concentration in this fluid is considered diagnostic of CNS rabies infection—and spread by this route could be quite fast.183 Additionally, rabies virions have been identified in intercellular spaces in the CNS by electron microscopy. Rabies antigen can be found in essentially all parts of the CNS and, although limited mostly to neurons, can also be found in oligodendrocytes.115

The rabies virus can infect a wide variety of cells in culture; no explanation for its localization to neurons in vivo has been found.124

After wide CNS involvement, the virus passes centrifugally through neural axoplasm to a wide variety of tissues, including salivary glands, corneas, and skin of the head and neck, sites at which identification of the virus may aid in the diagnosis of clinical illnesses. The route of spread to the periphery was demonstrated over 90 years ago, when Bartarelli sectioned nerves to salivary glands and found that the glands subsequently did not contain rabies virus.22 Even within the salivary gland, the virus appears to spread by neural networks and not between adjacent epithelial cells.67

An element of immunopathology is produced by disseminated rabies infection. Among persons exposed to rabies, those immunized with early vaccines who subsequently developed infections did so more rapidly than did unvaccinated individuals, a phenomenon termed “early death.” Experimental confirmation of this feature has been achieved by injecting mice with a lethal quantity of rabies virus and immunosuppressing a portion of them. The immunosuppressed animals survived 20% to 25% longer than unsuppressed animals, but their survivals were shortened to those of the control animals when they were injected with antirabies antibody. Additionally, cytolytic T cells appear to be a significant component of the protective response to rabies virus. Avirulent strains of rabies virus induce rabies specific cytolytic T cells, but virulent strains do not.145

Pathologic alterations in the CNS infected by rabies are surprisingly mild, unless supportive care has kept the patient alive for several weeks, which allows much more extensive, necrotic lesions to develop.165,177 Leptomeningeal congestion is the only grossly visible change typically found. Mild edema may be present if the patient has been hypoxic. Pressure grooves are rare. The meninges may be cloudy if severely inflamed.155

Typical histologic features are perivascular cuffing by mononuclear inflammatory cells, microscopic collections of reactive glial cells known as Babes nodules (named for the man who first described them in 18927), and areas of neuronal degeneration and neuronophagia. Some leptomeningeal inflammation is usually present. Spongiform degeneration similar to that found in prion diseases has been described in animals, particularly in skunks.67

Van Gehuchten and Nelis described a striking proliferation of the capsular cells surrounding ganglionic neurons that pushed these cells apart and separated them by a dense cellular layer. The neurons also contained degenerative changes. Subsequent studies have found the Van Gehuchten–Nelis changes to be present in almost everyone dying with rabies—and to be a much more consistent and reliable diagnostic feature than are viral inclusions.204,205

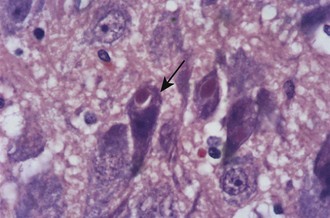

Negri bodies are the best-known histologic feature of rabies and were the first viral inclusions to be found (Figure 60-8). Negri described these cytoplasmic inclusions in 1903 and considered them parasites that caused the disease.146 Entirely independently, Bosc described identical inclusions in two separate papers published the same year, but he is rarely recognized.34,35 Negri bodies are eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions. Some contain a small, basophilic inner body, or innerkörperchen, and are known as lyssa bodies. They are found almost entirely within neurons; although most common in Ammon’s horn and Purkinje cells of the cerebellum, they may be seen in any part of the central nervous system, particularly in humans. Inclusions may be seen in other tissues, such as the salivary gland, skin, cornea, and pancreas, as well, but are not seen in the ependyma and choroid plexus.

The appearance of the inclusion bodies varies in different animal species, and uninfected animals such as cats commonly contain cytoplasmic inclusions that easily could be confused with rabies bodies.195

By electron microscopy, three types of bodies have been identified: one composed of a granular matrix of viral protein and typical virus particles, a second composed of matrix and tubular structures, and a third composed of matrix alone. Invaginations of cytoplasm into the inclusion give rise to the innerkörperchen, indicating that Negri bodies and lyssa bodies are both diagnostic of rabies.155

Clinical Features

“Although the clinical features of classical rabies are said to be too well known to require description, few clinicians practicing outside the tropical endemic zone have ever seen the disease, and the rare cases presenting in Europe and North America are often misdiagnosed.”215

Pain, paresthesias, or symptoms such as burning, itching, or numbness at the site of the bite or in the bitten limb are the most common early symptoms. Paresthesias may result from proliferation of rabies virus in the spinal cord at the level at which the nerves enter from the bite site.92 In Thailand, this initial symptom often takes the form of severe itching that can lead to frenzied scratching and extensive excoriations.215 This symptom is so well known among the Thai people, and animal bites are so common in that country, that any cause of itching or dysesthesia, even contact dermatitis, can lead to anxiety months to years after an animal exposure.224

Systemic symptoms usually develop later and are largely nonspecific. Local symptoms may not appear at all. One-third or less of all patients initially have symptoms that suggest the etiology of their infection to physicians who do not commonly encounter the disease. Complaints include malaise, chills, fever, or fatigue. Symptoms that suggest an upper respiratory infection are common and include sore throat, cough, and dyspnea. Gastrointestinal symptoms include anorexia, dysphagia, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Headache, vertigo, irritability, or anxiety and apprehension suggest CNS involvement. However, even advanced rabies often has nonspecific features.53,151 Hypoventilation and hypoxia are common during the prodrome and early acute neurologic phase, and the cause is not understood. Cardiac involvement is common and is manifested by tachycardia out of proportion to the fever; hypotension, congestive failure, or even cardiac arrest may ensue.92

Two clinical forms of human rabies are recognized. The furious, encephalitic, or agitated form that is associated with periodic episodes of hyperactivity, restlessness, or agitation is considered most typical. This form of rabies is characterized by periodic opisthotonic spasms or convulsions, particularly in response to tactile, auditory, visual, or olfactory stimuli (aerophobia and hydrophobia). Episodes of disorientation, sometimes with hallucinations or violent behavior, often alternate with periods of lucidity, which can be particularly horrifying because the patient recognizes the nature of his or her illness. The terror associated with hydrophobia has been labeled “powerful but indescribable.” Episodes of priapism, increased libido, insomnia, nightmares, and depression may suggest a psychiatric disorder. Patients maintained with supportive therapy progressively deteriorate, become comatose, lose peripheral nerve function, lose brainstem function, and die.92,215

Hydrophobia has been described in only 32% of recent U.S. patients,92 although one recent U.S. rabies victim, an 11-year-old boy, was so afraid of water he would not even take a bath.50 Experienced observers in Thailand have described hydrophobia as a violent, jerky contraction of the diaphragm and accessory muscles of inspiration that is triggered by attempts to swallow liquids and by other stimuli. Usually it is not associated with neck or throat pain or with laryngopharyngeal spasms. It has been likened to respiratory myoclonus (Leeuwenhoek’s disease). When patients lapse into coma, hydrophobia is typically converted into cluster breathing with long apneic periods.215

The variability of the clinical manifestations of rabies may result from heterogeneity in wild or “street” rabies viral populations (as contrasted with “fixed” viral strains maintained in laboratories), even in the viruses infecting a single animal. Rabies viruses isolated from a boy who died after being bitten by a fox and propagated by intracerebral inoculation of white mice produced three distinctly different forms of disease in the mice.102

The second clinical form of rabies, the paralytic, dumb, or Guillain-Barré–like form, is characterized by progressive paralysis without an initial furious phase. Even though the paralytic form of the disease does not appear to be as familiar to some health care providers, 20% to 30% of human rabies victims present in this manner.3,224 Other animals also have furious or dumb rabies presentations.148 Paralytic rabies is more common after rabid vampire bat bites, in persons injected with fixed virus strains, and in persons who have received postexposure vaccination.92 Distinction from Guillain-Barré syndrome may be difficult, although individuals with that disorder usually do not have urinary incontinence, which is common in rabies-infected persons.116

Individual case reports make clear that every patient is different. The most common misdiagnoses are psychiatric or laryngopharyngeal disorders.116 Physicians at QSMI, who have vast clinical experience, consider inspiratory spasms to be the most reliable clinical sign of rabies, particularly in comatose patients, regardless of whether the disease was initially furious or paralytic. Such respirations also have been described as rapid, irregular, or jerky, termed apneustic.

In addition, most of the QSMI patients have myoedema, particularly in the region of the chest, deltoid muscles, and thighs.219,224 However, this phenomenon, a brief, unpropagated, localized muscle contraction that appears in response to percussion with a tendon hammer, has not been confirmed as an important sign of paralytic rabies.116

Because the signs and symptoms are so nonspecific and often are rather mild at onset, many patients with rabies are not hospitalized the first time they are seen by a physician. (Two patients who died in the United States, one between 1960 and 1980 [the year of death was not stated] and the second in 2008, were never hospitalized.32) When admitted, most patients have a fever, which may be mild, but commonly is above 39.4° C (103° F). Of the 38 individuals who died of rabies in the United States between 1960 and 1980, 24 (63%) had difficulty swallowing, but only one-half of those had definite hydrophobia or aerophobia; 27 (72%) manifested excitement or agitation, 24 (63%) had paralysis or weakness, and 12 (32%) had hypersalivation. Dysesthesias at the exposure site were described by 19 (79%) of the 24 individuals who had an identifiable bite or similar exposure.3

Of the 28 patients diagnosed before death, 26 had a history of an animal exposure. Only four of eight patients diagnosed after death had this history. All 12 patients with hydrophobia were diagnosed before death.3

The duration of illness for patients not given supportive care averages 7.3 days and ranges from 2 to 23 days. For patients who are given supportive care, the average duration of illness is 25.3 days, with a range of 7 to 133 days.3,195

“The following [therapeutic] measures have … been tried in clinical rabies, but without any evidence of effectiveness: administration of vidarabine; multisite intradermal vaccination with cell-culture vaccine; administration of α-interferon and rabies immunoglobulin by intravenous as well as intrathecal routes; and administration of anti-thymocyte globulin, high doses of steroids, inosine pranobex, ribavirin and the antibody-binding fragment of immunoglobulin G.”219 In a recent review of the management of rabies in humans, a combination of some specific therapies was suggested. The authors point out that essentially no individuals with clinical rabies survive, and the best therapy often is palliative.117

Subclinical Rabies

Although clinical rabies in humans is a uniformly lethal infection with only six (perhaps seven) recognized exceptions, subclinical infections probably occur. Low titers of rabies virus neutralizing antibodies have been found in Canadian Inuit hunters and their wives, as well as in unimmunized students and faculty members of a veterinary medical school.116 In Nigeria, 28.6% of 158 healthy humans who had no history of exposure to rabies or of any antirabies prophylaxis were found to have serum-neutralizing antibodies against rabies. (Antibodies against Mokola virus [genotype 3] and Lagos bat virus [genotype 2] also were found in 7.5% and 2.5% of these individuals.) The investigators suggested that these individuals had been infected, but the infection had been halted before the virus had entered nerves. An attenuated strain of rabies virus also has been suggested as the cause of such antibodies, but an as-yet-unidentified virus of the Lyssa group, or even some other cross-reacting infectious agent, could be responsible.150 Among 48 family members of Peruvians who died following rabid vampire bat bites in 1990, seven had antirabies antibody levels that ranged from 0.14 to 0.66 international units. These antibodies could not be related to exposure to bats, exposure to other animals, or to other epidemiologic events.6

Some animals, including dogs, have significant amounts of nonspecific virus-neutralizing antibodies in their sera. Up to 20% of raccoons in Virginia and Florida180,229 and 20% to 40% of mongooses on Grenada have antirabies antibodies, which may be evidence of nonfatal infections.82 Up to 80% of bats in crowded nurseries may have rabies antibodies.17 The only finding considered diagnostic of prior rabies infection is antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid.85,86

Even clinical rabies is not always fatal in animals. Pasteur observed that some dogs recovered from early symptoms of rabies and subsequently could not be infected by rabies virus injections.153 Recoveries from infections that produced paralysis have been described in two dogs;89 recovery from clinical rabies has also been described in mice, donkeys, bats,13 and pigs.16

Undiagnosed Rabies

Clearly, many rabies infections are not diagnosed in developing countries. The possibility that in industrialized countries a number of human rabies infections are not diagnosed and the true incidence of this infection is higher than reported is suggested by several considerations. The clinical manifestations usually are nonspecific, and many infections are diagnosed late in the course of their illness as the result of testing for any identifiable cause of encephalitis, or subsequently by autopsy examination of the central nervous system. Of the 38 human rabies infections in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, 8 (21%) were diagnosed after death. Subsequently, the percentage of infections diagnosed postmortem has been higher.52,217

In recent years in the United States, most individuals with rabies have no recognized exposure to potentially infective animals, yet an account of animal exposure often is the only stimulus for laboratory identification of rabies as the cause of the encephalitis.52

The significance of undiagnosed human rabies is uncertain. When the diagnosis is made, members of the patient’s family and all health care personnel who have had a significant exposure to the patient are given postexposure immunoprophylaxis. However, human-to-human transmission of rabies has been reported only following tissue or organ transplantation, except in two individuals in Ethiopia.90

Laboratory Diagnosis of Rabies

Currently available techniques for a definitive laboratory diagnosis of rabies usually are nondiagnostic in the early days of infection and become useful only a week or more after the onset of illness. The diagnosis of rabies should be confirmed as early as possible so that the number of persons exposed to the infection can be limited and therapy for those exposed can be initiated promptly. In industrialized nations, the number of persons exposed to a hospitalized rabies patient can number in the hundreds.163,200

If rabies is suspected, a complete set of samples should be collected for testing by all currently available diagnostic procedures. Consultation is available from the CDC 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and should be obtained (877-554-4625; http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/). However, samples taken antemortem cannot definitively rule out rabies. If infection is seriously suspected, repeated sampling is needed.200 Samples can be transported overnight to the CDC or to state laboratories.

Brain biopsies should not be routinely performed because human rabies is so rare in industrialized countries and no effective treatment is available. If a biopsy is performed to rule out another condition, it can also be examined for rabies.200

Rabies virus often can be isolated from body fluids, particularly saliva and cerebrospinal fluid. The murine neuroblastoma cells used for isolation of rabies are more susceptible to that virus than any other cell line tested, and culture on such cells can usually provide a diagnosis within 24 hours. Mouse inoculation may take 15 to 30 days, although the time can be shortened by sacrificing mice starting 5 days after inoculation and examining the brains with fluorescent antibodies.195,219 In industrialized nations, facilities for such studies can be found in local, state, and national public health laboratories. In developing countries, they often are unavailable.

Rabies in Attacking Animals

Before 1903, the diagnosis of rabies in attacking animals was based entirely on the clinical features of the disease or on the presence of unusual material in the stomach of an animal that evidenced bizarre behavior. The dog that attacked Joseph Meister, the first recipient of Pasteur’s antirabies vaccine, was diagnosed as rabid because it had hay, straw, and wood in its stomach.8 In that year, Negri and Bosch described the typical neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, and for many years the laboratory diagnosis of rabies in animals depended on the detection of such bodies. However, only 60% to 80% of infected animals have identifiable inclusions.199 Typical inclusion bodies are scarce in Arctic foxes, for instance.75

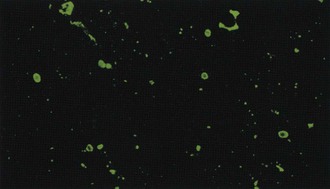

Immunofluorescent detection of rabies antigen in smears of cerebral tissues, which was introduced in 1958 and became widely used in the early 1960s,99 is far more reliable in experienced hands (Figure 60-9). Comprehensive analyses of the performance on survey examinations established that in major U.S. public health laboratories, the sensitivity of fluorescent antibody examination is nearly 100%. Fluorescent antibodies are used to identify rabies antigen in tissue culture (see later) because the rabies virus produces few cytopathogenic changes.

The major shortcoming of the procedure is its reduced sensitivity for rabies antigen in decomposed brain tissue. Some investigators have concluded that failure to identify rabies antigen with fluorescent antibodies in partially decomposed brain tissue cannot justify withholding postexposure therapy for exposed individuals.199

A procedure to confirm negative diagnoses is essential. Rabies diagnosis by intracerebral mouse inoculation was introduced in 1935 and demonstrated that only 85% to 95% of rabies infections could be identified by examination for inclusion bodies alone.193 Eventually, most laboratories, even those in developing countries, adopted adult or suckling mouse inoculation. Tissue-culture inoculation began with inoculation of chick embryo cells in 1942.195 Currently, tissue-culture isolation on mouse neuroblastoma cells is used, is far faster, and is also the most sensitive technique for confirming negative immunofluorescence examination results, at least in laboratories with suitable facilities and appropriate personnel.36,174,195 The rabies virus does not produce cytopathic changes in tissue culture, and fluorescent labeled antibodies must be used to diagnose the infection.

Postexposure Rabies Therapy

Postexposure treatment for humans consists of reducing the viral inoculum by cleansing the wound as thoroughly as possible, administering antiserum to help control viral reduplication and spread (passive immunization), and administering rabies vaccine to establish immunity to the virus before signs of infection appear (active immunization). “Rabies vaccination is a race between the active immunity induced by vaccination and the natural course of infection.”208

Identifying Exposure

Nonbite exposure consists of contamination of cutaneous wounds—including scratches, abrasions, and weeping skin rashes—with saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, or brain tissue from a rabid animal. If the material is dry, it is considered noninfectious.37 Contamination with urine from a rabid animal or person is not considered an exposure, even though rabies viruses have been isolated from kidneys and urine. A laboratory technician cut by a broken specimen container was given postexposure therapy.68

Exposure of medical personnel or family members caring for patients with rabies is a significant problem. High-risk contact is defined as a percutaneous (through needlestick or open wound) or mucous membrane contact with saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, or brain tissue. Such contact is considered essentially the same as bite and nonbite exposures to rabid animals. Individuals who have had a high-risk contact should receive postexposure immunoprophylaxis. However, routine infection isolation procedures, including respiratory precautions, minimize the risk for medical personnel caring for patients with rabies.37

In areas where canine rabies is not enzootic, which includes all of the United States except for the area along the border with Mexico (particularly southern Texas), a healthy domestic dog or cat that bites a person should be confined and observed for 10 days, particularly if the animal has been previously vaccinated. A veterinarian should evaluate any illness during confinement. If rabies is suspected, the animal should be humanely killed and its head should be shipped to a qualified laboratory.56 The head must be refrigerated during shipping. Examinations for rabies cannot be reliably performed on decomposed brain tissues.200

Such confinement and observation were judged safe for exposures to ferrets in 1998. Scientific evidence that the same quarantine period would be adequate for wolf hybrids does not exist, because studies of pathogenesis and virus shedding have not been performed. Hybrids that bite humans should be euthanized immediately, and their heads should be shipped to reliable laboratories.148

The significance of the laboratory’s qualifications was emphasized by the death from rabies of a U.S. citizen in 1981 after he was bitten by a dog in Mexico. The dog’s head was shipped to a Mexican laboratory, where it was examined with Sellers’ stain instead of a fluorescent antibody technique. Because no evidence of rabies was found with this less-sensitive technique, he was not given postexposure therapy.152 In a Thai investigation, 13 of 404 rabid animals diagnosed with fluorescent antibodies did not have Negri bodies identifiable with Sellers’ stain.187

Any stray or unwanted animal should be killed immediately and its head submitted for rabies examination. Euthanasia does not have to be delayed for further development of the infection in an attacking animal for a reliable diagnosis to be made.200

No one in the United States has died of rabies when the attacking dog or cat has been healthy after 10 days of observation.189 However, dogs injected with an Ethiopian strain of rabies virus excreted virus in the saliva up to 13 days before signs of disease were observed,88 and dogs that have recovered from experimental rabies excrete virus in saliva for as long as 6 months after recovery.91

If an attacking dog or cat is rabid or is suspected to be rabid, postexposure therapy should be initiated at once. However, a reliable determination of the presence or absence of rabies in animals can usually be completed in less than 1 day.200 If the dog or cat escapes and is not suspected to be rabid, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends that local public health officials be consulted.56

In a study of postexposure therapy practices in the emergency departments of a number of university hospitals from all parts of the United States, the most frequent inappropriate administration of therapy was for animals that could be observed for 10 days. The most common failure to administer postexposure therapy was for animals that could not be observed. The investigators emphasized that physicians often failed to use the expert consultative services available 24 hours a day from their local health departments or the CDC.141

In the United States, any exposure to a skunk, raccoon, bat, fox, or other carnivore, including bears and cougars, should be considered a rabies exposure. Treatment should be initiated immediately, except when the exposure has occurred in a part of the continental United States known to be free of rabies and the results of immunofluorescent testing are to be available within 48 hours. If the animal is captured, it should be killed and its head shipped to a qualified laboratory immediately. The signs of rabies in wild animals, including wolf hybrids, are not consistent enough or sufficiently well known for a 10-day observation period to reliably determine whether the animal was rabid.56

Small rodents (squirrels, hamsters, guinea pigs, gerbils, chipmunks, rats, and mice) and rabbits are rarely found to be infected with rabies and have not been known to produce rabies in humans. ACIP recommends that local health officials be consulted following a bite by a rodent or rabbit.56

Initial Wound Management

Immediate and thorough cleansing of bite wounds with soapy water to reduce the viral inoculum is an essential and highly effective component of postexposure therapy. Fishbein, former Chief of the Viral and Rickettsial Zoonoses Branch of the CDC, has stated, “Local treatment is perhaps the single most effective means of preventing rabies.” He also has said, “In some groups exposed to a single rabid animal and many laboratory investigations, local wound care alone has been found to be as or more important than vaccine alone.”92 Vodopija has declared, “Washing the wound with soap and water or with other substances that are lethal to rabies virus may be crucial for survival, irrespective of subsequent immunization.”210 Fangtao, who has had extensive experience with rabies in China, asserts, “The protective effect of each (wound care, immune globulin, and vaccine) should be considered equivalent.”83 Neglect of the wound or inadequate wound care has resulted in rabies in individuals who received ideal immunotherapy.24,56

Many experimental studies have shown that the duration of the incubation period following rabies exposure is inversely proportional to the size of the viral inoculum—a large inoculum produces generalized infection in a much shorter time than does a small inoculum.67 If rabies vaccine is to induce immunity before infection appears, it must have sufficient time. Following a severe rabies exposure, such as a bite about the head or neck, or multiple bites, a major reduction in the number of virus organisms introduced may be essential to allow time for immunization.

In experimental studies, the best results have been obtained by thoroughly cleaning the wound with soap and water and then irrigating it with a virucidal agent such as povidone–iodine or a 1% solution of benzalkonium chloride (Zephiran). Soap neutralizes benzalkonium chloride and must be completely rinsed from the wound before it is irrigated with the detergent. With deep wounds, only virucidal substances, such as benzalkonium chloride or povidone–iodine, have been found to be effective. If neither of these agents is available, 70% alcohol (ethanol) or iodine, either tincture or aqueous solution, can be instilled in the wound. The best cleansing agent that can be obtained immediately must be used.37,219 If these measures are painful, which is often the case when they are carried out with appropriate vigor, the area can be anesthetized with a local anesthetic.

This vital procedure is often neglected, particularly in developing countries. In a study of 250 patients with rabies seen at the Sassoon Hospital in Pune, India (the eighth-largest city in India with a population over 3.5 million), the wound had been washed with soap and water for only nine patients.184

Appropriate measures to prevent bacterial infection, including antibiotics if indicated, and tetanus prophylaxis should also be instituted.37,173 The WHO Expert Committee and others recommend that bites not be sutured.37,43,56,219

Rabies Immune Globulin

Although proposed and investigated by Babes and colleagues over a century ago,9 the benefit of hyperimmune serum immediately after rabies exposure was established only about 55 years ago. The most dramatic study was initiated by Koprowski and carried out in Iran in 1954. Twenty-nine persons were bitten by a single rabid wolf. Thirteen individuals with bites about the head were treated with antiserum and neurally derived vaccine; only one died. Five individuals with similar bites received vaccine alone; three died.19,20,22

Similar results were demonstrated in China with a much more effective cell-culture vaccine by Lin and associates, who suggested that immune serum might be effective because it stops virus from entering susceptible cells (nerves).84 The need for immune serum with human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV) has been demonstrated by the death from rabies in a 29-year-old female U.S. citizen in Rwanda who received prompt therapy with HDCV but not with hyperimmune serum.77

Measurements of the antibody response to earlier rabies vaccines demonstrated that immune serum reacted with the vaccine and limited the antibody response in the first 7 to 10 days of administration. These data were considered evidence of passive immunity that was essential for early control of the rabies virus, particularly when the viral inoculum was large and the incubation period before the development of clinical rabies was likely to be short.19 However, with contemporary cell-culture vaccines that have a concentration of 2.5 international units/mL, such inhibition of the serum-neutralizing antibody response is not seen.210

The only rabies immune globulin licensed for use in the United States is human rabies immune globulin (HRIG), which is prepared by cold ethanol fractionation from plasma from hyperimmunized human donors and is virtually free of significant side effects.225

When immune serum is given, it is usually of equine origin, which costs only about 10% as much as does HRIG.223 However, contemporary highly purified equine rabies immune globulin (ERIG) is not associated with the 15% to 46% incidence of serum sickness typical of older equine antirabies serum.43 In 3575 individuals treated at the QSMI, ERIG from Pasteur Vaccins of France, Sclavo of Italy, and the Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute produced allergic reactions in 0.87%, 3.58%, and 6.19% of the recipients, respectively. The reactions were uniformly mild and lasted less than a week with appropriate therapy. Only 9 of the 66 patients with reactions required steroid therapy; the remainder were satisfactorily treated with analgesics and antihistamines. ERIG is also produced in developing countries, but the purification procedures and potency criteria have not been published, and these products may be associated with a higher incidence of adverse reactions.

At QSMI, an initial intradermal injection of horse serum is administered, and individuals who present with sensitivity are treated with HRIG. One 17-year-old male did not react to the intradermal injection, but with subsequent injections he had an anaphylactic reaction that was successfully treated with epinephrine, hydrocortisone, and chlorpheniramine.223,225

Equine F(ab′)2 fragment rabies immunoglobulin is also used. In a study of 7660 patients in the Philippines, of 151 patients with laboratory-confirmed exposure, two died of rabies: a 4-year-old girl who had multiple deep lacerations on the nape, neck, and shoulders, and an 8-year-old boy who only received postexposure prophylaxis on the day of exposure. Local adverse reactions were documented in 35 individuals (0.46%); systemic adverse reactions were documented in 104 individuals (1.36%). Only two subjects had documented local adverse reactions within 30 minutes of immunization, and 11 individuals with systemic adverse reactions were documented to be having possible allergic reactions.162

Currently, all agencies recommend injection of as much immune globulin as possible around the bite site.219,225 For bites on the fingers and similar locations where only a limited amount of globulin can be injected locally, the remainder should be injected intramuscularly.37 For individuals with multiple bites, which is common with rabid dog attacks in developing countries, the immune globulin may have to be diluted with saline to achieve uniform injections. The syringe used to inject immune globulin must not be used to inject vaccine, which would be inactivated by residual antiserum.

Rabies Vaccines

Louis Pasteur revolutionized rabies therapy—and all of medicine—on July 7, 1885, when he began administering rabies vaccine to Joseph Meister, a 9-year-old boy who had been bitten 14 times by a dog that was killed and diagnosed as rabid because its stomach contained hay, straw, and fragments of wood.209,211 Although the rabies diagnosis in this animal may be suspect, and the boy may not have developed a clinical infection, Pasteur in 1886 observed only a single failure in a series of 688 treatments, many of whom must have been exposed to rabid animals and would have been expected to die without therapy.7 Meister’s only employment as an adult was as a security guard for the Pasteur Institute.193

Pasteur’s first rabies vaccine was produced from rabid rabbit spinal cords that were allowed to dry to attenuate the virus. After 15 days, the cords were noninfectious, so the first injections were made with 14-day-old spinal cords, and subsequent injections were made with cords that had been dried for shorter times.197,208 Roux and Callmette demonstrated that desiccated rabbit spinal cords retained appropriate virulence when preserved in glycerin, which greatly facilitated the production and storage of such vaccine.44,171 Although other vaccines were soon developed, the Pasteur rabbit spinal cord vaccine was administered at the Pasteur Institute of Paris as recently as 1953.208

Subsequently, similar vaccines have been prepared in brain tissues from various animals, particularly goats and sheep, containing virus killed with formaldehyde, phenol, or β-propiolactone.108,197 These preparations are collectively known as Semple or neural tissue vaccines, and Semple’s introduction of such vaccines in 1911 was a significant advance. In 1955, Fuenzalida and Palacios in Chile introduced the use of suckling mice less than 3 days old for the preparation of neurally derived vaccines. Such animals have little cerebral myelin and are thought to yield a product that contains less myelin basic protein. Currently, animals no older than 1 day are used. In Thailand, this vaccine has been found to be as poorly immunogenic and to be associated with as many side effects as are other similar vaccines,95,219,224 but other investigators have found the incidence of neural reactions to be lower.209 At the present time, neural tissue vaccines are still employed for a large percentage of all postexposure rabies therapy worldwide because they are inexpensive. Of 50 million doses of rabies vaccine administered worldwide each year, 20 million are still neural tissue vaccines.39