R

R on T phenomenon. Arises when the R wave of a ventricular ectopic beat falls on the T wave of the preceding beat. At the middle of the T wave, the myocardium is partly depolarised and partly repolarised, and thus vulnerable to establishment of re-entrant and circulatory conduction, leading to VF or VT.

R wave. First upward deflection of the QRS complex of the ECG (see Fig. 59b; Electrocardiography). Tends to increase in size from V1 to V6, with an accompanying reduction in size of S wave across these leads. Loss of this ‘R wave progression’, with a sudden increase in R wave size in V5 or V6, may indicate old anterior MI. In V1–6, at least one normally exceeds 8 mm, but none exceeds 27 mm.

Rabeprazole sodium. Proton pump inhibitor; actions and effects are similar to those of omeprazole.

Rabies. Infection caused by a lyssavirus of the rhabdovirus family, eradicated from Britain in 1902; however, occasional cases thought to have originated outside the UK have occurred in animals, e.g. dogs and bats. Fewer than 5 cases occur annually in Europe and the USA. Spread mainly via domestic dogs and cats, but also by foxes, bats and other wildlife. Transmitted via infected saliva penetrating broken skin or intact mucosa; the virus replicates in local muscle then migrates proximally along peripheral nerves to dorsal root ganglia and the CNS, eventually causing lethal encephalitis. Incubation period is usually 20–90 days in humans, but may be 4 days to several years.

Radford nomogram. Diagram showing the relationship between tidal volume, patient’s weight and respiratory frequency. Used to aid appropriate selection of ventilator settings for children and adults. Now rarely used.

Radial artery. Terminal branch of the brachial artery. Arises in the antecubital fossa, level with the radial neck, and runs distally on the tendons and muscles attached to the radius (biceps tendon, supinator, pronator teres, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus). Lies deep to brachioradialis muscle in the upper forearm, but subcutaneous in the lower forearm and easily palpable, especially over the distal quarter of the radius. Runs deep to abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons at the radial styloid, entering the anatomical snuffbox. Then enters the palm between the first and second metacarpals, forming the deep palmar arch. Branches include a superficial palmar branch (enters the palm superficial to the flexor retinaculum), which supplies the muscles of the thenar eminence before anastomosing with the superficial palmar arch. At the wrist, it is a common site for palpation of the pulse and for arterial cannulation.

Radial nerve (C5–T1). Terminal branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. Descends in the posterior upper arm, passing laterally behind the middle of the humerus in the radial groove. Crosses the antecubital fossa anterior to the elbow joint, between brachialis and brachioradialis. Descends under brachioradialis lateral to the radial artery in the forearm, passing posteriorly proximal to the wrist to end on the dorsum of the hand as digital branches.

axillary: to deltoid, teres minor and skin of the posteromedial upper arm.

axillary: to deltoid, teres minor and skin of the posteromedial upper arm.

– to triceps, brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus.

See also, Brachial plexus block; Elbow, nerve blocks; Wrist, nerve blocks

Radiation. Emission of energy in the form of waves or particles. Includes emission of electromagnetic waves (e.g. light), most of which is non-ionising (does not have sufficient energy to overcome electron binding energy). Ionising radiation may result in displacement of electrons in organic material with the potential for tissue damage, and includes:

γ-rays and X-rays: electromagnetic waves emitted from (γ-rays) or outside (X-rays) the nuclei of excited atoms. Have extremely high penetration of matter and thus pose a health hazard requiring radiation safety precautions. γ-Rays are used in radiotherapy and imaging, and X-rays in imaging.

γ-rays and X-rays: electromagnetic waves emitted from (γ-rays) or outside (X-rays) the nuclei of excited atoms. Have extremely high penetration of matter and thus pose a health hazard requiring radiation safety precautions. γ-Rays are used in radiotherapy and imaging, and X-rays in imaging.

Exposure to ionising radiation is kept to a minimum with appropriate storage and handling of radioisotopes, minimal use of X-rays and appropriate use of shielding. Formal training is required for those performing or directing radiology procedures.

Radiography in intensive care. Increasingly used as the range and quality of techniques and equipment available increase. Consultation with radiologists aids the proper selection and interpretation of many imaging techniques. In most cases, the use of mobile equipment results in less than optimal results but may be acceptable given the difficulty of transporting critically ill patients from the ICU; subtle changes between sequential films may be misleading if this is not taken into account. Investigations include CXR, ultrasound and CT and MRI scanning; bedside CT scanners are now available but MRI requires transport to the imaging department. Radioisotope scanning usually requires transfer from the ICU.

Practical considerations include the requirement for sedation and adequate monitoring during transport or the procedure itself, the interference of the procedure with background therapy including the requirement for moving the patient (e.g. to place films underneath), and the potentially adverse effects of radiological contrast media.

Radioisotope scanning. Use of radioisotopes to label certain parts of the body in order to investigate organ function, either directly or attached to circulating cells. Includes the following:

assessment of blood flow: cerebral blood flow, renal blood flow, lung perfusion scans (e.g. combined with ventilation scans in suspected PE).

assessment of blood flow: cerebral blood flow, renal blood flow, lung perfusion scans (e.g. combined with ventilation scans in suspected PE).

localisation of lesions: PE, bone metastases/infection/fracture, intra-abdominal sepsis.

localisation of lesions: PE, bone metastases/infection/fracture, intra-abdominal sepsis.

The radiation contained within the body after scanning is negligible, posing no risk to staff.

Radioisotopes. Isotopes of elements that undergo disintegration; i.e. the nucleus emits α, β or γ radiation either spontaneously or following a collision. Used clinically as labels to determine fluid compartments, blood flow, pulmonary  distribution and sites of infection. Technetium-99 m and xenon-133 are often suitable because they are easy to use and their half-lives are short. Also used to label metabolically active substances which are taken up by certain tissues, allowing imaging of the tissue concerned, e.g. fibrinogen labelled with iodine-123 accumulates in a clot and may be used to detect DVT. Therapeutic use includes radiotherapy.

distribution and sites of infection. Technetium-99 m and xenon-133 are often suitable because they are easy to use and their half-lives are short. Also used to label metabolically active substances which are taken up by certain tissues, allowing imaging of the tissue concerned, e.g. fibrinogen labelled with iodine-123 accumulates in a clot and may be used to detect DVT. Therapeutic use includes radiotherapy.

Radiological contrast media. Contain large molecules that absorb X-rays (e.g. barium [enteral] or iodine [enteral or iv]) or have paramagnetic properties (e.g. gadolinium) for MRI scanning. Adverse reactions may follow iv injection:

related to high osmolality (up to 7× that of plasma):

related to high osmolality (up to 7× that of plasma):

– initial hypervolaemia followed by osmotic diuresis and hypovolaemia.

– damage to red blood cells and vascular endothelium.

– reactions range from mild symptoms to cardiovascular collapse and death.

– adverse reactions are most likely to be due to direct histamine release or complement activation. ‘True’ anaphylaxis is not thought to occur.

direct toxicity: myocardial depression and systemic vasodilatation.

direct toxicity: myocardial depression and systemic vasodilatation.

Thus initial hypertension may be followed by prolonged hypotension. Renal failure may result from cardiovascular changes plus direct toxicity.

Incidence of reactions and renal failure is decreased by using low osmolar, non-ionic media. Other measures to prevent renal injury include adequate hydration and administration of N-acetylcysteine. Resuscitation equipment and drugs must always be available.

Radiology, anaesthesia for. Most radiological procedures require neither general anaesthesia nor sedation. Anaesthesia may be required for the very young, confused or agitated patients and those with movement disorders. Procedures include CT scanning, MRI, angiography and invasive procedures, e.g. embolisation of vascular lesions in neuroradiology.

• Main anaesthetic considerations:

remote location, often cramped conditions, with poor lighting.

remote location, often cramped conditions, with poor lighting.

old or incomplete anaesthetic/monitoring equipment.

old or incomplete anaesthetic/monitoring equipment.

Preoperative assessment and preparation should be as for any anaesthetic procedure.

Radiotherapy. Use of ionising radiation to treat neoplasms. May involve:

implantation of internal sources (brachytherapy), e.g. in gynaecological or CNS tumours.

implantation of internal sources (brachytherapy), e.g. in gynaecological or CNS tumours.

administration of radioactive radioisotopes, e.g. iodine-131 in hyperthyroidism, phosphorus-32 in polycythaemia.

administration of radioactive radioisotopes, e.g. iodine-131 in hyperthyroidism, phosphorus-32 in polycythaemia.

general condition of the patient: features of malignancy, site and nature of the neoplasm and drug therapy. Haematological abnormalities are common.

general condition of the patient: features of malignancy, site and nature of the neoplasm and drug therapy. Haematological abnormalities are common.

Techniques used include sedation or general anaesthesia using TIVA with propofol, or intermittent boluses of ketamine (especially in children).

McFadyen JG, Pelly N, Orr RJ (2011). Curr Opin Anaesthesiol; 24: 433–8

Randomisation. Technique for allocating subjects (e.g. patients to treatment groups in clinical trials) that reduces allocation bias when samples are compared. Ensures that factors such as age, sex and weight are randomly distributed amongst the groups; i.e. any difference in these factors is due to chance alone.

Ranitidine hydrochloride. H2 receptor antagonist; better absorbed and more potent than cimetidine, with fewer side effects. Does not inhibit hepatic enzymes or interfere with metabolism of other drugs. Oral bioavailability is about 50%. Plasma levels peak within 15 min of im injection and 2–3 h after oral administration; effect lasts about 8 h. Half-life is about 2 h. Undergoes hepatic metabolism and is excreted via urine, hence the dose is reduced in renal failure.

• Dosage:

150–300 mg orally bd. For prophylaxis against aspiration pneumonitis, 150 mg orally qds (e.g. in labour), or 2 h preoperatively (preferably preceded by 150 mg the night before).

150–300 mg orally bd. For prophylaxis against aspiration pneumonitis, 150 mg orally qds (e.g. in labour), or 2 h preoperatively (preferably preceded by 150 mg the night before).

• Side effects: blood dyscrasias, impaired liver function and confusion; all are rare.

Ranking, see Statistical tests

Rapacuronium bromide. Non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking drug, introduced in the USA in 1999 and withdrawn in 2001 just before its introduction in the UK, because of reports of fatal bronchospasm. Chemically related to vecuronium, it causes rapid onset of neuromuscular blockade (tracheal intubation possible within 60 s) with fast recovery (6–30 min depending on dosage) and was thus suggested as an alternative to suxamethonium.

Rapid opioid detoxification. Technique for treating opioid addiction by precipitating withdrawal using opioid receptor antagonists, e.g. naloxone or naltrexone, supposedly reducing relapse rates compared with conventional management. Ultra-rapid opioid detoxification refers to administration of general anaesthesia or heavy sedation for prolonged periods to reduce awareness or recall of unpleasant withdrawal symptoms whilst the opioid antagonists are given. The technique is controversial (especially the ultra-rapid form) since deaths have occurred and supportive evidence for its efficacy is poor.

Rapid sequence induction, see Induction, rapid sequence

Rate–pressure product (RPP). Product of heart rate and systolic BP, used as an indicator of myocardial workload and O2 consumption. It has been suggested that RPP should be maintained below 15 000 in patients with ischaemic heart disease during anaesthesia. Its usefulness has been questioned, since a proportional increase in rate may increase myocardial O2 demand more than the same increase in BP. A pressure–rate quotient (MAP/rate) of < 1 has been suggested as being a better predictor of myocardial ischaemia.

Reactance. Portion of impedance to flow of an alternating current not due to resistance; e.g. due to capacitance or inductance. Given the symbol X, and measured in ohms.

Rebreathing techniques, see Carbon dioxide measurement

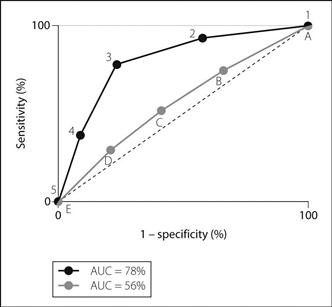

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Curves drawn to indicate the usefulness of a predictive test, originally derived from analysis of radar signals between the World Wars (i.e. did a deflection represent a real signal or just random noise; and if the former, with what degree of certainty?). For the test to be analysed (e.g. the usefulness of ASA physical status to predict mortality after anaesthesia), each cut-off level is examined in turn, and sensitivity and specificity calculated for it. Thus, for example, an ASA grade of 1 has high sensitivity (all deaths have an ASA grade of 1 or above) but low specificity (most patients with a grade of 1 or above do not die). For an ASA grade of 2, sensitivity is a little lower (some patients who die have a grade of 1, and will not be predicted by a grade of 2) whilst specificity is higher, although still poor (a grade of 2 is better at predicting death than a grade of 1, although most patients achieving 2 or above still do not die). The process continues until grade 5, which has low sensitivity (few of the deaths have a grade of 5) but high specificity (most patients who are graded 5 do, by definition, die). Sensitivity is plotted against (1 – specificity) and a curve obtained (Fig. 133); the area under the curve (AUC) represents the usefulness of the test: a perfect test includes 100% of the available area and one where prediction is no better than chance, 50%.

ROC curves may be drawn using continuous (e.g. C-reactive protein to predict infection), ordinal (e.g. ASA system) or nominal (e.g. presence of different features on the ECG to diagnose MI) scales. They may also be drawn for different tests in the same plot, allowing comparison between the tests. They also allow selection of the best cut-off to use clinically, usually the uppermost and most left-hand part of the curve, being the best compromise between sensitivity and specificity. They are increasingly used to analyse the usefulness of tests or scoring systems in anaesthesia and intensive care, including difficult tracheal intubation and other outcomes.

Receptor theory. States that receptors are specific proteins or lipoproteins located on cell membranes or within cells that interact selectively with extracellular compounds (agonists) to initiate biochemical events within cells. The structures of the agonist and receptor determine the selectivity and quantitative response. Drugs that interact with the receptor and inhibit the effect of an agonist are antagonists. Degree of binding to receptors is affinity; ability to produce a response is intrinsic activity.

Interaction of drug and receptor may resemble Michaelis–Menten kinetics. Covalent, ionic and hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces may be involved.

• Different types of receptor:

ligand-gated ion channels: direct opening of membrane pores allowing passage of ions (e.g. Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl−) across the membrane, e.g. nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Typically fast responses (< 1 ms).

ligand-gated ion channels: direct opening of membrane pores allowing passage of ions (e.g. Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl−) across the membrane, e.g. nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Typically fast responses (< 1 ms).

G protein-coupled receptors: binding to the receptor causes a change in the guanine binding properties of the neighbouring G protein, which then leads to the intracellular response, e.g. adrenergic receptors. Typically of the order of many milliseconds to seconds.

G protein-coupled receptors: binding to the receptor causes a change in the guanine binding properties of the neighbouring G protein, which then leads to the intracellular response, e.g. adrenergic receptors. Typically of the order of many milliseconds to seconds.

ligand-activated tyrosine kinases: binding at the cell surface causes activation of tyrosine kinase at the inner surface of the cell, which catalyses phosphorylation of target proteins via ATP, e.g. insulin receptors. Typically minutes to hours.

ligand-activated tyrosine kinases: binding at the cell surface causes activation of tyrosine kinase at the inner surface of the cell, which catalyses phosphorylation of target proteins via ATP, e.g. insulin receptors. Typically minutes to hours.

nuclear receptors: the lipid-soluble agonist passes through the cell membrane to interact with the receptor, leading to alteration of DNA transcription, e.g. corticosteroid and thyroid hormones. Typically up to several hours.

nuclear receptors: the lipid-soluble agonist passes through the cell membrane to interact with the receptor, leading to alteration of DNA transcription, e.g. corticosteroid and thyroid hormones. Typically up to several hours.

Recommended International Non-proprietary Names (rINNs), see Explanatory Notes at the beginning of this book

Record-keeping. The first anaesthetic chart was devised by Codman and Cushing in 1894 at the Massachusetts General Hospital, for recording of respiration and pulse rate. BP charting was included in 1901 at Cushing’s insistence. FIO2 was included by McKesson in 1911.

Careful record-keeping is now recognised as essential to chart preoperative risk factors, the perioperative course of anaesthesia and postoperative events/instructions. It is particularly useful when taking over another anaesthetist’s anaesthetic, and for providing information to those administering anaesthesia subsequently. Similarly, ICU records should chart physiological data, therapy and instructions relating to the stay of any patient in an ICU. Record-keeping is also important for teaching, research and audit, and is extremely important in medicolegal aspects of anaesthesia. Although tending to include similar information, anaesthetic and intensive care charts are not standardised nationally, although this has been suggested.

Automated anaesthetic record systems are increasingly used, sometimes incorporated into anaesthetic machines or ICU monitoring systems. They provide accurate, legible and complete documents for data acquisition and subsequent scrutiny. Data from monitoring devices are incorporated with information provided by the anaesthetist/intensive care staff (e.g. drug or other interventions), although lack of familiarity with keyboards or computers may be a hindrance.

Postoperative recovery and progress may be recorded on separate charts, or on the anaesthetic chart.

Recovery from anaesthesia. Period from the end of surgery to when the patient is alert and physiologically stable. Definition is difficult because some drowsiness may persist for many hours. Recovery testing is used for more precise investigation. Time to recovery depends on the patient’s condition, drugs given, their doses, and the patient’s ability to eliminate them. For inhalational anaesthetic agents, similar considerations as for uptake are involved, plus length of operation and degree of redistribution to fat. Thus blood gas solubility is the most important factor initially, but more potent agents (e.g. isoflurane) are more extensively bound to fat after prolonged anaesthesia than less potent ones, e.g. desflurane. For iv anaesthetic agents, initial recovery is due to drug redistribution from vessel-rich to vessel-intermediate tissues; subsequent course is related to the rate of clearance from the body. Thus propofol characteristically results in rapid clear-headed emergence, whereas thiopental is more likely to produce drowsiness lasting several hours, especially after repeated dosage. Recommendations for provision of recovery care (Association of Anaesthetists):

designated recovery rooms or areas should be used.

designated recovery rooms or areas should be used.

during transfer to the recovery area O2 should be administered, and appropriate monitoring performed.

during transfer to the recovery area O2 should be administered, and appropriate monitoring performed.

O2 should be administered at least until awake.

O2 should be administered at least until awake.

there should be criteria for discharge, including full consciousness, clear airway, respiratory and cardiovascular stability, adequate postoperative analgesia and control of PONV, stable temperature and prescription of postoperative drugs, including O2 and iv fluids as appropriate. There should be adequate handover during discharge from the recovery area.

there should be criteria for discharge, including full consciousness, clear airway, respiratory and cardiovascular stability, adequate postoperative analgesia and control of PONV, stable temperature and prescription of postoperative drugs, including O2 and iv fluids as appropriate. There should be adequate handover during discharge from the recovery area.

children should be recovered in a designated area.

children should be recovered in a designated area.

Patients are often placed on their side, e.g. the recovery position. In the ‘tonsillar position’, the pillow is placed under the loin and the trolley tipped head-down.

respiratory, e.g. hypoventilation, hypercapnia, hypoxaemia, airway obstruction, bronchospasm, aspiration of gastric contents.

respiratory, e.g. hypoventilation, hypercapnia, hypoxaemia, airway obstruction, bronchospasm, aspiration of gastric contents.

cardiovascular, e.g. hypotension, hypertension, arrhythmias, myocardial ischaemia.

cardiovascular, e.g. hypotension, hypertension, arrhythmias, myocardial ischaemia.

related to anaesthetic drugs, e.g. inadequate reversal of non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade, adverse drugs reactions, MH, dystonic reactions, emergence phenomena, central anticholinergic syndrome.

related to anaesthetic drugs, e.g. inadequate reversal of non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade, adverse drugs reactions, MH, dystonic reactions, emergence phenomena, central anticholinergic syndrome.

hypothermia, nausea and vomiting, shivering.

hypothermia, nausea and vomiting, shivering.

Recovery position. Position recommended for unconscious but spontaneously breathing subjects, assuming no contraindication, e.g. cervical spine injury. Encourages a clear airway and drainage of vomitus, secretions and blood away from the airway. Often used during recovery from anaesthesia.

Any recovery position is a compromise between the full prone position (better airway and drainage but more diaphragmatic splinting) and the full lateral position (less diaphragmatic splinting but less effective for the airway and less stable; also may be harmful in neck injury). Classically includes flexion of both arms with the upper hand placed under the jaw to support the airway (Fig. 134). The actual position adopted should reflect the particular circumstances of the case and the need to protect the airway, stabilise the neck and allow unhindered ventilation. It should be possible to observe the patient at all times and to turn him/her supine easily when required.

Fig. 134 Recovery position

staffed by fully trained personnel.

staffed by fully trained personnel.

placed near the operating suite, if possible near ICU.

placed near the operating suite, if possible near ICU.

open ward, allowing good patient observation.

open ward, allowing good patient observation.

at least two bays per operating theatre are recommended.

at least two bays per operating theatre are recommended.

each bay is equipped for monitoring (ECG, BP, O2 saturation) and patient care (suction, O2).

each bay is equipped for monitoring (ECG, BP, O2 saturation) and patient care (suction, O2).

a supply of iv equipment and fluids, blankets and airways should be available.

a supply of iv equipment and fluids, blankets and airways should be available.

adequate ventilation is required to remove exhaled anaesthetic gases.

adequate ventilation is required to remove exhaled anaesthetic gases.

• Drugs available should include:

analgesics, antiemetics, sedatives, anticonvulsants, naloxone, flumazenil.

analgesics, antiemetics, sedatives, anticonvulsants, naloxone, flumazenil.

doxapram, bronchodilators, corticosteroids, antihistamines.

doxapram, bronchodilators, corticosteroids, antihistamines.

anticholinergics, antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, diuretics, heparin.

anticholinergics, antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, diuretics, heparin.

antibiotics, anticholinesterases, neuromuscular blocking drugs, insulin, dextrose, dantrolene.

antibiotics, anticholinesterases, neuromuscular blocking drugs, insulin, dextrose, dantrolene.

Recovery testing. Ranges from simple clinical assessment to more sophisticated methods, e.g. used for experimental comparison between anaesthetic techniques and drugs. Routine testing is usually limited to assessment of general alertness and orientation, and ability to respond, drink, dress and walk where appropriate (e.g. day-case surgery).

• Sophisticated techniques used include tests of:

– assessing speed and number of errors made whilst performing set tasks:

– moving pegs from one set of holes in a board to another set.

– deleting every letter ‘p’ from a page of text.

– tracking moving targets with a pen or light.

– recall or recognition of objects, pictures, words or word associations shown a short time before.

– orientation in time and space.

cognitive function, e.g. adding/subtracting numbers, or adding values of different coins.

cognitive function, e.g. adding/subtracting numbers, or adding values of different coins.

physiological function, e.g. divergence of eyes caused by reductions in extraocular muscle tone.

physiological function, e.g. divergence of eyes caused by reductions in extraocular muscle tone.

Rectal administration of anaesthetic agents. Results in effective absorption of drugs because of a rich blood supply provided by communicating plexuses formed by the superior, middle and inferior rectal arteries and veins. Drugs undergo minimal first-pass metabolism, because the plexuses are anastomoses between portal and systemic circulations. The technique is usually restricted to children. Traditionally used more in continental Europe, e.g. France. Drugs used have included diazepam 0.4–0.5 mg/kg (widely used for treatment of convulsions in children), methohexital 15–25 mg/kg and thiopental 40–50 mg/kg as 5–10% solutions. Opioids and ketamine have also been given in this way. Diethyl ether was administered rectally by Pirogoff. Bromethol and paraldehyde were used in the 1920s to produce unconsciousness (basal narcosis).

Rectus sheath block. Performed as part of abdominal field block or alone to reduce pain from abdominal incisions. Abdominal contents are not anaesthetised.

With the patient supine, a blunted needle is introduced 3–6 cm above and lateral to the umbilicus. A gentle ‘scratching’ motion may aid identification of the tough anterior layer of the sheath, puncture of which is accompanied by a click. The needle is advanced up to the resistance offered by the posterior layer of the sheath, and 15–20 ml local anaesthetic agent injected after negative aspiration. Deposition of solution between rectus muscle and posterior layer allows spread up and down, blocking the lower 5–6 intercostal nerves within the sheath. Spread between the muscle and anterior layer is limited by the tendinous intersections along its length. Multiple injections have been suggested between intersections, to improve spread, but the posterior layer is deficient below a point halfway between the umbilicus and pubis, and peritoneal puncture is more likely below this level.

Recurarisation. Recurrence of non-depolarising neuromuscular blockade after apparent reversal with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Originally described with tubocurarine in patients with impaired renal function, where the duration of action of the neuromuscular blocking drug exceeds that of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. Has been described with other neuromuscular blocking drugs.

Red cell concentrates, see Blood products

Reducing valve, see Pressure regulators

Refeeding syndrome. Clinical syndrome seen after reintroduction of nutrition to previously starved patients, often seen on ICU. First noted after World War II, when malnourished prisoners of war inexplicably died of cardiac failure after receiving a normal diet. Associated with any condition leading to malnutrition (e.g. anorexia nervosa, alcoholism, intra-abdominal sepsis).

restoration of carbohydrates as a dietary substrate leads to increased insulin secretion and activation of anabolic pathways. Hypophosphataemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypokalaemia and vitamin deficiency (particularly thiamine) may follow due to increased intracellular uptake on a background of whole body depletion.

restoration of carbohydrates as a dietary substrate leads to increased insulin secretion and activation of anabolic pathways. Hypophosphataemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypokalaemia and vitamin deficiency (particularly thiamine) may follow due to increased intracellular uptake on a background of whole body depletion.

depletion of ATP and 2,3-DPG leads to tissue hypoxia and mitochondrial dysfunction.

depletion of ATP and 2,3-DPG leads to tissue hypoxia and mitochondrial dysfunction.

hyperglycaemia and electrolyte disturbances as above.

hyperglycaemia and electrolyte disturbances as above.

muscle weakness, contributing to respiratory failure and difficulty weaning from ventilators.

muscle weakness, contributing to respiratory failure and difficulty weaning from ventilators.

Wernicke’s encephalopathy due to thiamine deficiency.

Wernicke’s encephalopathy due to thiamine deficiency.

correction of electrolyte deficiencies before reintroducing feeding.

correction of electrolyte deficiencies before reintroducing feeding.

Byrnes MC, Stangenes J (2011). Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care; 14:186–92

Referred pain. Pain felt in a somatic site remote to the source of pain, usually visceral; e.g. diaphragmatic pain is felt in the shoulder tip. The aetiology is obscure, but is thought to be related to the embryological segment from which the organ arose, e.g. diaphragm from the neck region, and heart from the same region as the arm.

Reflex arc. Involves predictable, repetitive stereotypic responses to a particular sensory stimulus. Consists of sense organ, afferent neurone, one or more synapses, efferent neurone and effector. The afferent neurones enter the spinal cord via dorsal roots or brain via cranial nerves; the efferent neurones leave via ventral nerve roots or corresponding motor cranial nerves. Also involved in autonomic functions. The simplest reflex arc is monosynaptic, e.g. knee jerk and other stretch reflexes involving muscle spindles. Polysynaptic reflex arcs (two or more synapses) include the withdrawal reflex. Widespread effects may result from activation of a single reflex arc because of ascending, descending, excitatory and inhibitory interneurones.

Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, see Complex regional pain syndrome

Reflux, see Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Refractometer, see Interferometer

Refractory period. Period during and following the action potential during which the neurone is insensitive to further stimulation. Subdivided thus:

Refrigeration anaesthesia. Use of cold to reduce pain sensation. Used by Larrey in 1807, although the effect of cold on pain has been recognised for centuries. Up to 3 h packing in ice was recommended for operations through the thigh. The principle is still used today, e.g. ethyl chloride spray.

Regional anaesthesia. Term originally coined by Cushing to describe techniques of abolishing pain using local anaesthetic agents as opposed to general anaesthesia. Pioneers included Halstead, Corning and Labat in the USA and Bier, Braun and Lawen in Europe.

infiltration anaesthesia, Vishnevisky technique and tumescent anaesthesia.

infiltration anaesthesia, Vishnevisky technique and tumescent anaesthesia.

peripheral nerve blocks: plexus and single nerve blocks.

peripheral nerve blocks: plexus and single nerve blocks.

central neuraxial blockade: epidural and spinal anaesthesia.

central neuraxial blockade: epidural and spinal anaesthesia.

IVRA and intra-arterial regional anaesthesia.

IVRA and intra-arterial regional anaesthesia.

others, e.g. interpleural analgesia.

others, e.g. interpleural analgesia.

• Advantages of regional anaesthesia:

conscious patient, able to assist in positioning, and warn of adverse effects (e.g. in carotid endarterectomy and TURP). There is less interruption of oral intake, especially beneficial in diabetes mellitus.

conscious patient, able to assist in positioning, and warn of adverse effects (e.g. in carotid endarterectomy and TURP). There is less interruption of oral intake, especially beneficial in diabetes mellitus.

reduction of certain postoperative complications, e.g. atelectasis and DVT, possibly myocardial ischaemia.

reduction of certain postoperative complications, e.g. atelectasis and DVT, possibly myocardial ischaemia.

absolute: patient refusal, anaesthetist’s inexperience and localised infection.

absolute: patient refusal, anaesthetist’s inexperience and localised infection.

relative: abnormal anatomy or deformity, coagulation disorders, previous failure of the technique, and neurological disease or other medicolegal considerations.

relative: abnormal anatomy or deformity, coagulation disorders, previous failure of the technique, and neurological disease or other medicolegal considerations.

Specific contraindications may exist for specific techniques.

– preoperative assessment and preparation as for general anaesthesia.

– full explanation of the procedure, and consent.

– monitoring should be applied as for general anaesthesia, i.e. before starting the procedure and continued throughout it.

– aseptic technique should be observed.

– for nerve or plexus blocks, short-bevelled needles are traditionally used to minimise nerve contact, although nerve damage may be greater should the nerve be impaled. Nerve stimulators (using 0.3–1.0 mA current lasting 1–2 ms and delivered at 1–3 Hz) increase the success of many blocks and may reduce damage further. A distant ground electrode is required. The needle (preferably sheathed) is placed near the target nerve and stimulated until paraesthesia or twitches are elicited; the output is reduced, the needle repositioned and the process repeated.

– if sedation is used, care should be taken to ensure that respiratory and cardiovascular depression does not occur. Analgesic drugs (e.g. N2O or opioid analgesic drugs) may be used to supplement incomplete blockade. General anaesthesia may be used as a planned part of the technique, or if the technique is unsuccessful.

– close monitoring and supervision should continue as for general anaesthesia.

– patients should be advised to protect insensate limbs e.g. using a sling for upper limb blocks.

– patients should be warned of potentially unpleasant paraesthesia as the block recedes.

– neurological complications may only become apparent once the block has worn off.

technical: direct trauma to nerves, blood vessels and pleura, breakage of needles or catheters.

technical: direct trauma to nerves, blood vessels and pleura, breakage of needles or catheters.

associated with positioning of the patient, e.g. compression of an anaesthetised limb.

associated with positioning of the patient, e.g. compression of an anaesthetised limb.

local anaesthetic toxicity: intravascular injection or systemic absorption.

local anaesthetic toxicity: intravascular injection or systemic absorption.

excessive spread, e.g. total spinal block during epidural anaesthesia, or phrenic nerve block during brachial plexus block.

excessive spread, e.g. total spinal block during epidural anaesthesia, or phrenic nerve block during brachial plexus block.

those of specific techniques, e.g. hypotension following spinal anaesthesia.

those of specific techniques, e.g. hypotension following spinal anaesthesia.

others, e.g. injection of the wrong solution through catheters.

others, e.g. injection of the wrong solution through catheters.

Regional tissue oxygenation. Important because shock and hypoxaemia cause redistribution of blood flow and alter the metabolic properties of cells; global measurements thus fail to detect areas of local ischaemia. Measurement of regional tissue oxygenation may be useful in critically ill patients because deficiencies may be involved in the development and continuation of MODS. Lack of evidence of benefit and technical difficulties have hindered the more intricate techniques from becoming routine practice. Methods of assessment include:

blood lactate levels (> 2 mmol/l suggests insufficient oxygen delivery): a late marker.

blood lactate levels (> 2 mmol/l suggests insufficient oxygen delivery): a late marker.

mixed venous O2 saturation (

mixed venous O2 saturation ( ), measured using repeated blood sampling or continuous oximetry via a pulmonary artery catheter. Regional

), measured using repeated blood sampling or continuous oximetry via a pulmonary artery catheter. Regional  (e.g. hepatic =

(e.g. hepatic =  ; jugular =

; jugular =  ) can be determined using indwelling catheters.

) can be determined using indwelling catheters.

intestinal regional capnography (i.e. gastric tonometry). Measures PCO2 in an air- or saline-filled tonometric balloon, placed in the GIT.

intestinal regional capnography (i.e. gastric tonometry). Measures PCO2 in an air- or saline-filled tonometric balloon, placed in the GIT.

surface or tissue O2 electrodes: based upon the Clark electrode (see Oxygen measurement), they are formed of a noble metal (e.g. gold, silver, platinum). Change in voltage between the anode and cathode is proportional to the amount of O2 reduced at the cathode.

surface or tissue O2 electrodes: based upon the Clark electrode (see Oxygen measurement), they are formed of a noble metal (e.g. gold, silver, platinum). Change in voltage between the anode and cathode is proportional to the amount of O2 reduced at the cathode.

imaging using online microscopic observation of the microcirculation.

imaging using online microscopic observation of the microcirculation.

Regression, see Statistical tests

Regurgitation. Term usually describing passive passage of gastric contents into the pharynx. Silent, thus aspiration of gastric contents may occur unnoticed. Normally prevented by the lower oesophageal sphincter; however, swallowed dyes have been found to stain areas of the pharynx and larynx during/after anaesthesia in normal patients.

Relative analgesia. Technique used in dental surgery involving nasal administration of subanaesthetic concentrations of N2O, e.g. 10% in O2, slowly increased to 30–50%. Verbal contact is maintained at all times, and the concentration of N2O reduced if excessive drowsiness occurs. Performed by the dentist, it depends partly on suggestion.

Relative risk reduction. Indicator of treatment effect in clinical trials. For a reduction in incidence of events from a% to b%, it equals ( [a − b] ÷ a)%. Gives an overestimated impression of treatment effect if events are rare, and an underestimate if events are common.

See also, Absolute risk reduction; Meta-analysis; Number needed to treat; Odds ratio

Remifentanil. Ultra-short-acting synthetic opioid analgesic drug, 2000 times more potent than morphine, introduced in the UK in 1997. Available as a white powder for reconstitution to a 0.1% solution which is stable for 24 h at room temperature. Further diluted for administration; in adults a 50 µg/ml solution is recommended by the manufacturer. Approximately 70% protein-bound. Rapidly metabolised by non-specific plasma and tissue esterases to remifentanil acid (very low potency) and excreted renally. Its context-sensitive half-life is about 3 min regardless of the duration of infusion; thus provides a rapid recovery when stopped.

Because it is cleared so rapidly and completely, patients very soon experience pain postoperatively unless longer-acting analgesics are given before discontinuation. In addition, it has been suggested that the hyperalgesia that can occur following remifentanil infusions may be due to upregulation of NMDA receptors. Has been used via patient-controlled analgesia during labour (see Obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia). Not recommended for epidural or spinal use since the formulation contains glycine. Postoperative respiratory depression may occur if any drug is left in the dead space of iv lines and subsequently flushed with other drugs or fluids.

• Dosage:

Remote ischaemic preconditioning, see Ischaemic preconditioning

Renal blood flow (RBF). Normally 1200 ml/min (400 ml/100 g/min); i.e. 22% of cardiac output.

direct: circumferential electromagnetic flow measurement, Doppler or thermodilution techniques.

direct: circumferential electromagnetic flow measurement, Doppler or thermodilution techniques.

– clearance methods: a substance neither metabolised nor taken up by the kidney, and completely cleared, is required, e.g. para-amino hippuric acid (PAH). Clearance then equals renal plasma flow. RBF = plasma flow divided by (1 – haematocrit). Continuous iv infusion of PAH is required; inaccuracies may occur since clearance of PAH is only 90% in humans. Radioactive markers have been used; almost 100% cleared, they require only a single injection.

arterial BP: maintained by autoregulation at MAP between 70 and 170 mmHg in normal subjects.

arterial BP: maintained by autoregulation at MAP between 70 and 170 mmHg in normal subjects.

sympathetic nervous system: stimulation causes vasoconstriction and reduction of RBF, and also increases release of renin and prostaglandins. Dopamine may increase RBF by vasodilatation via dopamine receptors.

sympathetic nervous system: stimulation causes vasoconstriction and reduction of RBF, and also increases release of renin and prostaglandins. Dopamine may increase RBF by vasodilatation via dopamine receptors.

renin/angiotensin system: angiotensin II decreases RBF via vasoconstriction, and increases aldosterone secretion. The latter increases fluid retention, which inhibits further renin release.

renin/angiotensin system: angiotensin II decreases RBF via vasoconstriction, and increases aldosterone secretion. The latter increases fluid retention, which inhibits further renin release.

vasopressin: causes renal vasoconstriction, especially cortical.

vasopressin: causes renal vasoconstriction, especially cortical.

intravascular volume: in haemorrhage, autoregulation is overridden, with vasoconstriction and intrarenal redistribution of blood away from the cortex.

intravascular volume: in haemorrhage, autoregulation is overridden, with vasoconstriction and intrarenal redistribution of blood away from the cortex.

prostaglandins: increase cortical blood flow, and reduce medullary blood flow.

prostaglandins: increase cortical blood flow, and reduce medullary blood flow.

atrial natriuretic peptide: causes vasodilatation, although effects on RBF are unclear. May alter blood flow distribution.

atrial natriuretic peptide: causes vasodilatation, although effects on RBF are unclear. May alter blood flow distribution.

RBF and GFR are reduced by most anaesthetic agents, mainly via reduced cardiac output and BP. Volatile agents are also thought to interfere with autoregulation, although some benefit may arise from the vasodilatation they cause, maintaining blood flow. Urine output therefore often falls perioperatively.

Other factors include pre-existing renal disease or conditions predisposing to renal failure or impairment, e.g. vascular surgery, toxic drugs, trauma, jaundice, hypovolaemia.

Renal failure. Loss of renal function causing abnormalities in electrolyte, fluid and acid–base balance with increases in plasma urea and creatinine. Divided into acute and chronic renal failure.

• Acute renal failure (see Acute kidney injury for definitions, diagnosis and management).

• Chronic renal failure (CRF):

irreversible, and often follows acute kidney injury.

irreversible, and often follows acute kidney injury.

features (may not be present until GFR falls below 15 ml/min):

features (may not be present until GFR falls below 15 ml/min):

– malaise, anorexia, confusion leading to convulsions and coma. Peripheral and autonomic neuropathy may occur.

– oedema, pericarditis, hypertension (in 80%; thought to result from increased renin/angiotensin system activity, sodium and water retention and secondary hyperaldosteronism), peripheral vascular disease, cardiac failure. Ischaemic heart disease is 20 times more common in CRF patients.

– nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea.

– osteomalacia, muscle weakness, bone pain, hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphataemia.

– pruritus, skin pigmentation, poor healing, increased susceptibility to infection.

– normocytic normochromic anaemia: caused by reduced erythropoietin production, shortened red cell survival and bone marrow depression. Impaired platelet function may cause bruising and bleeding.

– hypernatraemia or hyponatraemia may occur. Hyperkalaemia is usual, but hypokalaemia may follow diuretic therapy. Acidosis is common.

– reduction of dietary protein.

– control of hypertension and cardiac failure.

– erythropoietin is increasingly used for anaemia.

– dialysis.

• Anaesthesia in renal failure:

– features of the underlying disease must be assessed, e.g. diabetes, hypertension.

– assessment for the above features of renal failure, in particular cardiovascular complications, fluid and electrolyte and acid–base derangements. Dialysis may be required; if it has been recently performed, patients are often hypovolaemic, and therefore vulnerable to perioperative hypotension. Anaemia rarely requires transfusion because of its chronicity with compensatory mechanisms. Patients may be at risk from aspiration of gastric contents if autonomic neuropathy is present.

– drugs taken commonly include antianginal and antihypertensive drugs, insulin and corticosteroids.

– pre-existing arteriovenous fistulae or shunts should be noted.

– premedication as required.

– potassium-containing iv fluids should be avoided.

– drugs whose actions are not terminated by renal excretion are preferred. Thus a common technique consists of propofol followed by atracurium and isoflurane, sevoflurane or desflurane.

– drugs that accumulate in renal failure (e.g. morphine) should be used with caution. Patients are more sensitive to many iv agents, including opioids, because of smaller volumes of distribution and reduced plasma protein levels.

– suxamethonium is not contraindicated unless there is pre-existing peripheral neuropathy or hyperkalaemia.

– nephrotoxic drugs (e.g. NSAIDs) should be avoided. Enflurane has been avoided because of fluoride ion formation, although the need for this is controversial. Previous concerns regarding sevoflurane and compound A formation are not thought to be relevant in humans.

– regional techniques are often suitable, e.g. brachial plexus block for fistula formation.

postoperatively: close attention to fluid balance is required.

postoperatively: close attention to fluid balance is required.

Dennen P, Douglas IS, Anderson R (2010). Crit Care Med; 38: 261–75

Renal failure index, see Renal failure

Renal transplantation. First performed in 1950, and now widespread but limited mainly by the supply of kidneys. Cadaveric graft survival is up to 80–90% at 2 years. Previously considered an emergency and performed on unprepared patients, but the importance of proper preoperative assessment and preparation is now generally accepted. Dialysis is usually performed within 24 h before surgery.

• Anaesthetic problems and techniques are as for chronic renal failure and transplantation. Additional points:

general anaesthesia is preferred, although epidural and spinal anaesthesia have been successfully used.

general anaesthesia is preferred, although epidural and spinal anaesthesia have been successfully used.

direct arterial blood pressure measurement is not necessarily required (although ischaemic heart disease and cardiac failure are common in these patients); CVP monitoring is routinely used to guide perioperative fluid therapy. Optimal hydration is vital to support graft function.

direct arterial blood pressure measurement is not necessarily required (although ischaemic heart disease and cardiac failure are common in these patients); CVP monitoring is routinely used to guide perioperative fluid therapy. Optimal hydration is vital to support graft function.

mannitol, furosemide, calcium channel blocking drugs and dopamine are sometimes given before the vessels to the new kidney are unclamped, in order to stimulate urine production and improve renal function.

mannitol, furosemide, calcium channel blocking drugs and dopamine are sometimes given before the vessels to the new kidney are unclamped, in order to stimulate urine production and improve renal function.

transient hypertension may follow unclamping of the renal vessels.

transient hypertension may follow unclamping of the renal vessels.

there is an increased incidence of kidney rejection in patients who have received blood transfusion during transplantation; preoperative correction of anaemia with erythropoietin should be considered.

there is an increased incidence of kidney rejection in patients who have received blood transfusion during transplantation; preoperative correction of anaemia with erythropoietin should be considered.

Both live and cadaveric donors should be well hydrated to maintain urine output before harvesting.

Sarinkapoor H, Kaur R, Kaur H (2007). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand; 51: 1354–67

Renal tubular acidosis. Group of conditions characterised by decreased ability of each nephron to excrete hydrogen ions (cf. renal failure, where the overall number of functioning nephrons is reduced, but those that remain excrete more hydrogen ions than normal). Characterised by normal GFR, metabolic acidosis, hyperchloraemia and a normal anion gap. May be associated with distal tubule dysfunction (type 1), proximal tubule dysfunction (type 2; usually associated with other abnormalities of proximal tubule function, e.g. Fanconi’s syndrome), or aldosterone deficiency or resistance (type 4). Type 3 is now considered a combination of types 1 and 2 and not a separate entity. Acidosis may be severe, and accompanied by marked hypokalaemia (hyperkalaemia in type 4). Treatment includes alkali (e.g. oral sodium bicarbonate) in types 1 and 2, thiazides in type 2 and mineralocorticoid therapy in type 4.

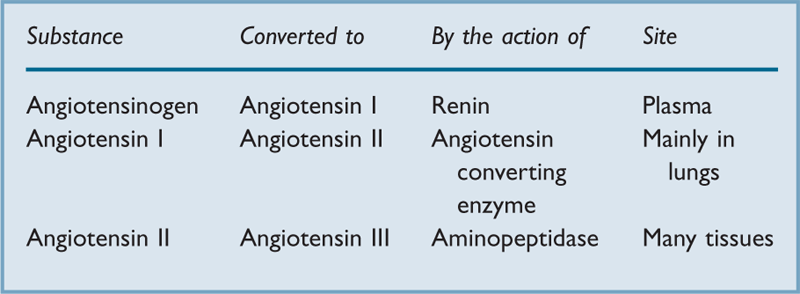

Renin/angiotensin system. Renin, a proteolytic enzyme (mw 37 kDa), is synthesised and secreted by the juxtacapillary apparatus of the renal tubule. Formed from two precursors, prorenin and preprorenin, its half-life is about 80 min. Secretion is increased in hypovolaemia, cardiac failure, cirrhosis and renal artery stenosis. Secretion is decreased by angiotensin II and vasopressin. Renin cleaves the circulating glycoprotein angiotensinogen with subsequent production of the peptides angiotensin I, II and III, involved in arterial BP control and fluid balance (Table 38). Angiotensin I is a precursor for angiotensin II, a powerful vasoconstrictor with a half-life of a few minutes. It causes aldosterone release from the adrenal cortex, and noradrenaline release from sympathetic nerve endings. It also stimulates thirst and release of vasopressin, and acts directly on renal tubules, resulting in sodium and water retention. Some may also be produced in the tissues. Angiotensin III also causes aldosterone release and some vasoconstriction.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists are used to treat hypertension. Aliskiren, a direct renin inhibitor, has recently been introduced.

Angiotensin II or its analogues have been used as vasopressor drugs when α-agonists are unable to correct severe hypotension, e.g. during surgery for hepatic tumours secreting vasodilator substances.

Reperfusion injury. Tissue injury resulting from restoration of blood flow after a period of ischaemia. Mechanisms include intracellular calcium excess, cellular oedema and free radicals. Although any tissue may be affected, most work has focused on cardiac function following hypoxic insult or hypoperfusion. Arrhythmias and myocardial stunning (reversible impairment of cardiac function) may also follow reperfusion.

Reptilase time, see Coagulation studies

Reserpine. Antihypertensive drug, rarely used now because of its unfavourable side-effect profile. Depletes postganglionic adrenergic neurones of noradrenaline by irreversibly preventing its reuptake from axoplasm into storage vesicles. Crosses the blood–brain barrier and depletes central amine stores. Effects may last 1–2 weeks.

Reservoir bag. Usually 2 litre capacity in most adult anaesthetic breathing systems and 0.5–1.0 litre for paediatric use; its volume must exceed tidal volume. Movement indicates ventilation, but estimation of tidal volume from the degree of movement is inaccurate. Made of rubber (increasingly, latex-free), distending when under pressure; maximal pressure is thus prevented from rising above about 60 cmH2O (Laplace’s law).

Residual volume (RV). Volume of gas remaining in the lungs after maximal expiration. About 1.5 litres in the average 70 kg male; measured as for FRC. Increased RV accounts for most cases of increased FRC.

Resistance. In electrical terms, the ratio of the potential difference across a conductor to the current flowing through it (Ohm’s law). Measured in ohms (Ω). Resistance to flow of a fluid through a circular tube is analogous to this; it equals the ratio of the pressure gradient along the tube to the flow through it.

Resistance vessels. Term given to those blood vessels involved in regulation of SVR. 50% of resistance to blood flow is due to arterioles, which are thus the main regulators of SVR and therefore distribution of cardiac output.

Resonance. Situation in which an oscillating system responds with maximal amplitude to an alternating external driving force. Occurs when the driving force frequency coincides with the natural oscillatory frequency (resonant frequency) of the system. May occur in pressure transducer systems if long, compliant tubing is used. May give rise to artefacts in the arterial waveform during direct arterial BP measurement.

Resonium, see Polystyrene sulphonate resins

Respirators, see Ventilators

Respiratory centres, see Breathing, control of

Respiratory depression, see Hypoventilation

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS; Hyaline membrane disease). Occurs in approximately 1% of all live births, almost exclusively in premature babies. Caused by deficiency of surfactant. Surfactant is normally detectable in the fetal lung at 24 weeks’ gestation, although reversal of amniotic fluid lecithin/sphingomyelin ratio (related to fetal lung maturity) only occurs at 30 weeks. Decreased lung compliance, increased work of breathing and alveolar collapse may lead to respiratory failure, with characteristic granular appearance of the CXR.

Treatment is directed towards preventing hypoxaemia with CPAP initially, although IPPV is usually necessary, whilst trying to avoid O2 toxicity, barotrauma and retinopathy of prematurity. Exogenous surfactant given immediately after birth decreases mortality. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation has been used.

Respiratory exchange ratio. Estimation of respiratory quotient derived from expired CO2/inspired O2 measurements, thus dependent on ventilation.

Respiratory failure. Defined as an arterial PO2 < 8 kPa (60 mmHg) breathing air at sea level, and at rest, without intracardiac shunting.

type I failure: hypoxaemia with normal or low arterial PCO2. Usually due to

type I failure: hypoxaemia with normal or low arterial PCO2. Usually due to  mismatch, with intrapulmonary right-to-left shunt if severe. Causes include chest infection, asthma, pulmonary embolus, pulmonary oedema, PE, ARDS, aspiration pneumonitis. O2 therapy improves hypoxaemia due to

mismatch, with intrapulmonary right-to-left shunt if severe. Causes include chest infection, asthma, pulmonary embolus, pulmonary oedema, PE, ARDS, aspiration pneumonitis. O2 therapy improves hypoxaemia due to  mismatch but not shunt; the response to breathing 100% O2 may indicate the degree of shunt. PCO2 is often low because of hyperventilation in response to hypoxaemia.

mismatch but not shunt; the response to breathing 100% O2 may indicate the degree of shunt. PCO2 is often low because of hyperventilation in response to hypoxaemia.

type II failure (ventilatory failure): hypoxaemia accompanied by arterial PCO2 > 6.5 kPa (49 mmHg). Causes are as for hypoventilation. Acute exacerbation of COPD is a common cause.

type II failure (ventilatory failure): hypoxaemia accompanied by arterial PCO2 > 6.5 kPa (49 mmHg). Causes are as for hypoventilation. Acute exacerbation of COPD is a common cause.

Diagnosis is made by arterial blood gas interpretation, but may be suspected clinically by signs of hypoxaemia and hypercapnia, with tachypnoea and use of accessory respiratory muscles.

sitting the patient up increases FRC and often improves oxygenation.

sitting the patient up increases FRC and often improves oxygenation.

oxygen therapy: should be used cautiously in type II failure if chronic hypercapnia is suspected.

oxygen therapy: should be used cautiously in type II failure if chronic hypercapnia is suspected.

aminophylline may have an inotropic action on the diaphragm and may reduce respiratory muscle fatigue; it is often used in neonates.

aminophylline may have an inotropic action on the diaphragm and may reduce respiratory muscle fatigue; it is often used in neonates.

carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may increase respiratory drive in COPD associated with hypercapnia.

carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may increase respiratory drive in COPD associated with hypercapnia.

respiratory stimulant drugs (e.g. doxapram) have been used to avoid IPPV, e.g. in COPD.

respiratory stimulant drugs (e.g. doxapram) have been used to avoid IPPV, e.g. in COPD.

CPAP or non-invasive positive pressure ventilation may improve oxygenation and ventilation, avoiding the need for tracheal intubation.

CPAP or non-invasive positive pressure ventilation may improve oxygenation and ventilation, avoiding the need for tracheal intubation.

IPPV may be required if PCO2 is rising or the patient is exhausted. Criteria similar to those used in weaning from ventilators have been suggested for institution of IPPV. Tracheostomy may be necessary to aid weaning from mechanical ventilation.

IPPV may be required if PCO2 is rising or the patient is exhausted. Criteria similar to those used in weaning from ventilators have been suggested for institution of IPPV. Tracheostomy may be necessary to aid weaning from mechanical ventilation.

intravenous oxygenator, extracorporeal oxygenation and extracorporeal CO2 removal have been used.

intravenous oxygenator, extracorporeal oxygenation and extracorporeal CO2 removal have been used.

Respiratory function tests, see Lung function tests

Respiratory muscle fatigue. Inability of the respiratory muscles to sustain tension with repeated activity. May be caused by:

decreased central drive, e.g. caused by CNS depressant drugs (e.g. opioid analgesic drugs).

decreased central drive, e.g. caused by CNS depressant drugs (e.g. opioid analgesic drugs).

increased ventilatory load caused by increased airway resistance and reduced compliance (e.g. asthma, COPD) or increased demand (e.g. exercise, fever, hypoxaemia).

increased ventilatory load caused by increased airway resistance and reduced compliance (e.g. asthma, COPD) or increased demand (e.g. exercise, fever, hypoxaemia).

Causes hypercapnic respiratory failure and difficulty in weaning from ventilators. Treatment is directed at the underlying cause.

Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Brochard L (2009). J Appl Physiol; 107: 962–70

Respiratory muscles. Muscle actions during:

– diaphragm (the most important muscle of respiration) flattens and moves 1–2 cm caudally.

– external intercostal muscles (fibres pass downwards and forwards) lift the upper ribs and sternum up and forwards, and the lower ribs mainly up and outwards. The first rib remains fixed.

forced inspiration: as above, with the diaphragm descending up to 10 cm, plus accessory muscles:

forced inspiration: as above, with the diaphragm descending up to 10 cm, plus accessory muscles:

quiet expiration: passive recoil of chest and abdomen.

quiet expiration: passive recoil of chest and abdomen.

– mainly abdominal muscles (internal and external oblique, rectus abdominis).

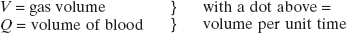

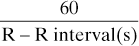

Respiratory quotient (RQ). Ratio of the volume of CO2 produced by tissues to the volume of O2 consumed per unit time. At rest, it depends on the type of substrate being utilised: RQ of carbohydrate is 1, RQ of fat 0.7 and that of protein about 0.82. Also depends on the ratio of aerobic to anaerobic respiration that is occurring; after strenuous exercise RQ may rise transiently to up to 2 (due to excess lactic acid reacting with available bicarbonate).

Whole body RQ calculated by measurement of expired CO2 and inspired O2 only approximates to true RQ, since these volumes are affected by respiration. The term respiratory exchange ratio (R) is therefore becoming more commonly used for this measurement.

Respiratory sounds. Traditionally assessed with a stethoscope, more recently analysed by digital processing using microphones or accelerometers placed on the chest wall. Sounds arise from vibration of airways and movement of fluid films within them. The nature of the sounds depends on the tissue through which they pass, e.g. quiet or absent in pleural effusion and pneumothorax, increased transmission in consolidation. The pitch is related to the size of the airway involved and the density of the gas.

Range from under 100 Hz to over 1000–3000 Hz.

– wheezing: arises from the central/lower airways with a sinusoidal frequency (polyphonic), ranging from 100 Hz to over 1000 Hz.

Other sounds may occur (e.g. stridor), although not from the lung itself.

Gurung A, Scrafford CG, Tielsch JM, Levine OS, Checkley W (2011). Respir Med; 105: 1396–403

Respiratory stimulant drugs, see Analeptic drugs; Opioid receptor antagonists

Respiratory symbols. By convention, standardised thus:

P = pressure or tension

F = fractional concentration in dry gas mixture

f = respiratory frequency

C = content of a gas in blood

R = respiratory exchange ratio

S = saturation of haemoglobin with O2 or CO2

e.g. FIO2 = inspired fractional concentration of O2; PaO2 = arterial O2 tension.

SpO2 has been suggested as representing haemoglobin saturation as measured by pulse oximetry.

Respirometer. Device for measuring expiratory gas volumes. Examples:

Wright’s anemometer (axial turbine flowmeter): a design commonly integrated into ventilators. Expired gas is passed into its chamber through oblique slits, creating circular gas flow that causes rotation of a double-vaned turbine within the chamber. Rotation is measured and displayed as the volume of gas passing through the device, using an indicator needle attached to the vane, and a dial. Electrical versions are also available; rotations of a disc attached to the vane interrupt passage of light between an emitter and photosensitive cell mounted astride the disc. Less prone to inertia inaccuracies than the Wright’s respirometer.

Wright’s anemometer (axial turbine flowmeter): a design commonly integrated into ventilators. Expired gas is passed into its chamber through oblique slits, creating circular gas flow that causes rotation of a double-vaned turbine within the chamber. Rotation is measured and displayed as the volume of gas passing through the device, using an indicator needle attached to the vane, and a dial. Electrical versions are also available; rotations of a disc attached to the vane interrupt passage of light between an emitter and photosensitive cell mounted astride the disc. Less prone to inertia inaccuracies than the Wright’s respirometer.

others: include flowmeters, whose signals may be integrated to indicate volume.

others: include flowmeters, whose signals may be integrated to indicate volume.

Resuscitation, see Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Resuscitation Council (UK). Multiprofessional group formed in 1981 to facilitate education of lay and professional members of the population in the most effective methods of resuscitation. Aims of the Council include: encouraging research and study of resuscitation techniques; the promotion of training and education in resuscitation; and the establishment and maintenance of standards. The Council has published guidelines for CPR and has set up a series of advanced courses in adult and paediatric resuscitation (i.e. ALS, ILS).

Resuscitators, see Self-inflating bags

Reteplase. Recombinant plasminogen activator, used as a fibrinolytic drug in management of acute coronary syndromes. Has a longer half-life (13–16 min) than alteplase.

Reticular formation/activating system, see Ascending reticular activating system

Retrobulbar block. Performed to allow surgery to the globe of the eye, e.g. cataract extraction. Cranial nerves III and VI, and long and short ciliary nerves (branches of V1) are blocked within the cone formed by the extraocular muscles. Now rarely used due to its relatively high frequency of complications, including retrobulbar haemorrhage, intravascular and subarachnoid injection and globe perforation. Peribulbar block and sub-Tenon’s block are safer and equally effective alternatives.

With the patient supine and looking straight ahead, a 3.0 cm needle is inserted through the conjunctiva at the lower lateral orbital rim. It is passed backward and 10° upward until its tip has passed the mid-globe, then angled medially and upward to reach a point behind the globe at the level of the iris. After aspiration, 2–4 ml lidocaine with hyaluronidase 5 U/ml is injected.

Retrolental fibroplasia, see Retinopathy of prematurity

Retzius cave block. Used to supplement anaesthesia for prostatectomy and bladder surgery. The cave of Retzius is the space between the bladder and pubic symphysis, containing nerves of the sacral plexus and a venous plexus. After subcutaneous infiltration 2–3 cm above the pubis, an 8 cm needle is directed to the back of the symphysis. After negative aspiration for blood, 10 ml local anaesthetic agent with adrenaline is injected in the midline, with a further injection on each side.

Reuben valve, see Non-rebreathing valves

Revised trauma score (RTS). Trauma scale derived from the trauma score but simplified and with greater emphasis on the presence of head injury. Uses the Glasgow coma scale, systolic BP and respiratory rate, each assigned a value of 0–4 according to deviation from normal, with 0 representing the most severe. The values are added to give a total RTS, with a normal of 12. Superior to the trauma score at predicting outcome; a RTS of < 4 suggests the need for transfer to a specialist trauma unit.

Reye’s syndrome. Rare condition of unknown aetiology, characterised by vomiting, depression of consciousness and hepatic failure. Jaundice is typically absent or minimal. Usually occurs in children, typically following a viral illness; aspirin has been implicated in epidemiological studies and is thus contraindicated under 16 years of age. Thought to be due to an acquired mitochondrial abnormality. Treatment is mainly supportive, with correction of metabolic disturbances, cerebral oedema and raised ICP. Thought to be improved by administering up to a third of the fluid intake as 10% dextrose.

Reynolds’ number (Re). Dimensionless number predicting when flow of a fluid becomes turbulent:

Rhabdomyolysis, see Myoglobinuria

Rhesus blood groups. System of blood group antigens first described in 1939 following work on rhesus monkeys. Includes many antigens but the terms Rhesus (Rh)-positive and -negative usually refer to the D antigen, as it is the most immunogenic. Rh-negative individuals have no D antigen, and form anti-D antibodies when injected with Rh-positive blood. 85% of Caucasians are Rh-positive, 99% of Orientals.

blood transfusion reactions: administration of Rh-positive blood to Rh-negative individuals who have anti-D antibodies following previous exposure to Rh-positive blood.

blood transfusion reactions: administration of Rh-positive blood to Rh-negative individuals who have anti-D antibodies following previous exposure to Rh-positive blood.

Diagnosed clinically and by evidence of recent streptococcal infection. Traditionally treated with rest, penicillin, aspirin and corticosteroids, but the effect of drugs on valve disease is controversial. 50% of patients with carditis progress to valvular heart disease, which may not present until later in life. Mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected.

Anaesthetic management of patients previously affected is directed towards any existing valve disease and associated complications (e.g. cardiac failure, pulmonary hypertension).

[Karl Albert Ludwig Aschoff (1866–1942), German pathologist]

Carapetis JR, McDonald M, Wilson NJ (2005). Lancet; 366: 155–68

Rheumatoid arthritis (Rheumatoid disease). Systemic inflammatory disease with many features of connective tissue diseases. Characterised by symmetrical polyarthropathy, but affects other organs too. Three times more common in females; peak incidence is at ages 30–50 years. Up to 5% of females over 60 years are affected in the UK. Aetiology is unclear but may involve an immunological process triggered by infectious agents coupled with a genetic predisposition. Recent advances in treatment, including early therapy with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS), including biological agents which block tumour necrosis factor, appear to improve the course and severity of the condition.

– skeletal: temporomandibular joint involvement, atlantoaxial subluxation, reduced mobility of the lumbar/cervical spine.

– neuromuscular: nerve entrapment, sensory/motor neuropathy, myopathy.

– respiratory: restrictive defect due to pulmonary fibrosis and costochondral disease, pulmonary nodules, pleural effusions, cricoarytenoid arthritis.

– cardiovascular: ischaemic heart disease (often with ‘silent’ MI), pericarditis, heart block, coronary arteritis, peripheral vasculitis.

– haematological: anaemia (usually normochromic normocytic), leucopenia. Felty’s syndrome consists of rheumatoid arthritis, splenomegaly and leucopenia; thrombocytopenia, malaise and fever may occur.

– renal: amyloidosis, pyelonephritis, drug-related impairment.

drug therapy: may include NSAIDs, corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs. Gold may cause blood dyscrasias, peripheral neuritis, pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic and renal impairment. Penicillamine may cause blood dyscrasias, renal impairment, neuropathy and a myasthenia gravis-like syndrome.

drug therapy: may include NSAIDs, corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs. Gold may cause blood dyscrasias, peripheral neuritis, pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic and renal impairment. Penicillamine may cause blood dyscrasias, renal impairment, neuropathy and a myasthenia gravis-like syndrome.

– wrist and hand arthritis may preclude the use of patient-controlled analgesia.

[Augustus R Felty (1895–1963), US physician; Henrik SC Sjögren (1899–1986), Swedish ophthalmologist]

Samanta R, Shoukrey K, Griffiths R (2011). Anaesthesia; 66: 1146–59

Ribavirin (Tribavirin). Antiviral drug; a nucleoside, it inhibits DNA synthesis and is active against many RNA and DNA viruses, although usually reserved for treatment of respiratory syncytial viral infection and Lassa fever. Also used in combination with interferon alfa for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C.

Rib fractures. Middle ribs are most commonly affected. Fracture usually occurs at the posterior axillary line, the point of maximal stress. If the first three ribs are affected, injury to the aorta and tracheobronchial tree should be considered. If the lower ribs are involved, damage to liver, spleen and kidneys may occur. Pneumothorax and haemothorax may be present.

General management is as for chest trauma and abdominal trauma.

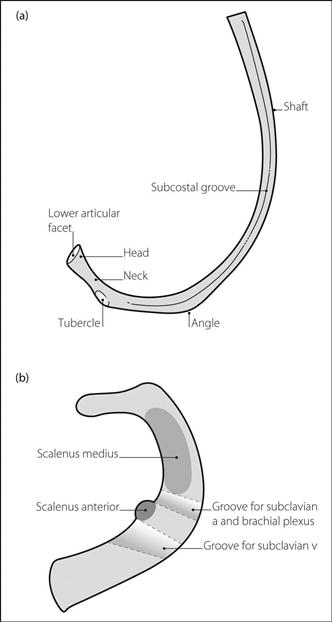

Ribs. Exist in 12 (thoracic) pairs, with occasional additional cervical or lumbar ribs. Attached to thoracic vertebrae posteriorly and costal cartilage anteriorly. Ribs 2–8 are typical (Fig. 135a), consisting of:

head: bears two facets for articulation with adjacent vertebrae.

head: bears two facets for articulation with adjacent vertebrae.

tubercle: articulates posteriorly with the transverse process of the corresponding vertebra.

tubercle: articulates posteriorly with the transverse process of the corresponding vertebra.

• The first rib is of particular anaesthetic importance because of its relationship to the brachial plexus and other structures (Fig. 135b). Features:

short, wide and flattened in the horizontal plane.

short, wide and flattened in the horizontal plane.

lower surface is smooth and lies on pleura.

lower surface is smooth and lies on pleura.

upper surface is grooved for the subclavian vessels and brachial plexus.

upper surface is grooved for the subclavian vessels and brachial plexus.

scalenus anterior and medius attach to the scalene tubercle and body of the rib respectively.

scalenus anterior and medius attach to the scalene tubercle and body of the rib respectively.

Rifabutin. Antituberculous drug used for prophylaxis against Mycobacterium avium in immunocompromised patients.

Rifampicin. Antibacterial drug, used primarily as an antituberculous drug but also in brucellosis, Legionnaires’ disease, severe staphylococcal infection, leprosy and as prophylaxis against meningococcal disease (thus may be given to ICU staff after caring for an infected patient or to household contacts). Causes hepatic enzyme induction and thus decreases the efficacy of oral contraceptives, anticoagulants and phenytoin.

RIFLE criteria Consensus staging classification of acute kidney injury described in 2004, consisting of five stages of increasingly severe impairment graded according to plasma creatinine (Cr) level, GFR and/or urine output (UO):

Risk: Cr > 1.5 × baseline/GFR > 25% decrease; UO < 0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 h.

Risk: Cr > 1.5 × baseline/GFR > 25% decrease; UO < 0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 h.

Injury: Cr > 2.0 × baseline/GFR > 50% decrease; UO < 0.5 ml/kg/h for 12 h.

Injury: Cr > 2.0 × baseline/GFR > 50% decrease; UO < 0.5 ml/kg/h for 12 h.

Loss: complete loss of renal function for > 4 weeks.

Loss: complete loss of renal function for > 4 weeks.

End-stage renal disease: complete loss of function for > 3 months.

End-stage renal disease: complete loss of function for > 3 months.

stages 1–3 corresponding to RIF categories; removal of ‘Loss’ and ‘End-stage’ categories.

stages 1–3 corresponding to RIF categories; removal of ‘Loss’ and ‘End-stage’ categories.

addition of an absolute increase in Cr of 26.5 µmol/l to stage 1.

addition of an absolute increase in Cr of 26.5 µmol/l to stage 1.

48 h timeframe specified for period of deterioration.

48 h timeframe specified for period of deterioration.

patients receiving renal replacement therapy automatically classed as stage 3.

patients receiving renal replacement therapy automatically classed as stage 3.

diagnostic criteria to be applied only after fluid optimisation.

diagnostic criteria to be applied only after fluid optimisation.

Right atrial pressure, see Cardiac catheterisation; Central venous pressure

Right ventricular function. The right ventricle (RV) receives blood from systemic and coronary veins, and pumps it into the left ventricle (LV) across the pulmonary vascular bed. The pulmonary bed is of low resistance, therefore RV pressures (15–25/8–12 mmHg) are lower than systemic. The low intraventricular pressure permits right coronary blood flow to be continuous throughout the cardiac cycle. The output of the right heart is influenced by its preload, contractility and afterload.