Quality and Safety in Anaesthesia

QUALITY

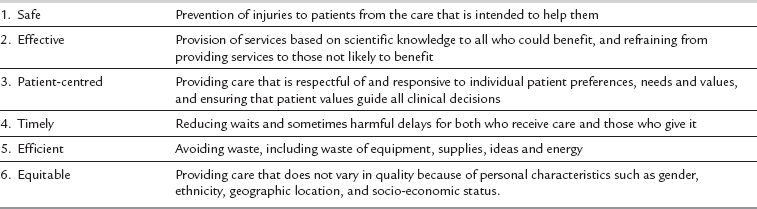

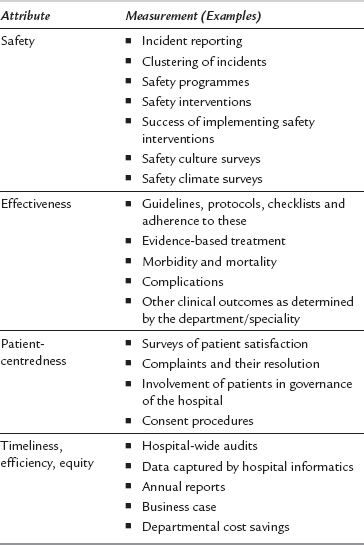

Various attempts have been made to define quality in health care systems precisely. In the IOM’s 2001 report Crossing the Quality Chasm, six aims were proposed to define ‘what healthcare should be’. The six aims, i.e. safety, effectiveness, patient-centredness, timeliness, efficiency and equity, provide components of a working definition of quality in healthcare systems (Table 44.1). The six aims can be used as the attributes of a comprehensive quality care system, which can be continuously monitored and improved. These six aims are the cornerstones for designing and delivering a quality service from which both patients and clinicians are likely to benefit in terms of better patient care, less suffering and increased productivity and satisfaction.

CULTURE OF QUALITY AND SAFETY

Understanding Generation of Errors: Systems Approach

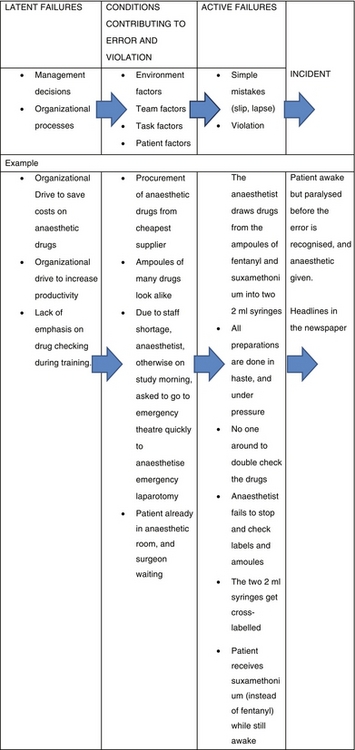

One central message from the IOM report has been that, in general, the cause of preventable deaths in healthcare systems is not incompetent or careless people, but bad systems. In order to reach this level of understanding, it is important to understand the aetiology of an error in complex organizations such as hospitals (Box 44.1). A safety incident should be seen in an organizational framework of latent failures – the conditions which produce error and violation – and active failures. This concept is captured in James Reason’s model of an organizational accident. It should be emphasized that some active failures (such as simple mistakes, lapse, fall, slip) have only a local context and can be explained by factors related to individual performance and/or the task at hand. However, it is now understood that major incidents evolve over time and involve many factors.

In the generation of an incident, organizational factors are the beginning of the sequence. These create latent failures which result from the negative consequences of management decisions, and organizational strategy and/or planning. The latent failures then permeate through departmental pathways to the workplace (e.g. the operating theatre complex). Here, they create conditions which allow violations and commission of errors. The errors generated in the workplace environment may be prevented by a front-end clinician (near-miss). However, a simple active failure on the part of the clinician at this stage allows the error to produce damaging outcomes. Figure 44.1 illustrates an example: how a medication error can result from a combination of latent failures, conditions contributing to error and violations, and active failure.

Focus on Safety Behaviour and Non-Technical Skills

Conscientiousness. Being sensible and meticulous, checking the information/drugs/equipment him/herself, ensuring that the job is done properly, and being thorough.

Conscientiousness. Being sensible and meticulous, checking the information/drugs/equipment him/herself, ensuring that the job is done properly, and being thorough.

Honesty. Accepting limitations, giving correct and complete information, accepting own mistakes, compliance with procedures and protocols.

Honesty. Accepting limitations, giving correct and complete information, accepting own mistakes, compliance with procedures and protocols.

Humility. Thanking colleagues, juniors and nurses for their help and contribution, taking and seeking advice from other members of the team.

Humility. Thanking colleagues, juniors and nurses for their help and contribution, taking and seeking advice from other members of the team.

Self-awareness. Knowing limitations, knowing when tired, sleepy or pre-occupied

Self-awareness. Knowing limitations, knowing when tired, sleepy or pre-occupied

Confidence. Knowing capabilities and being confident about them, able to speak up if necessary.

Confidence. Knowing capabilities and being confident about them, able to speak up if necessary.

Communication and Teamwork

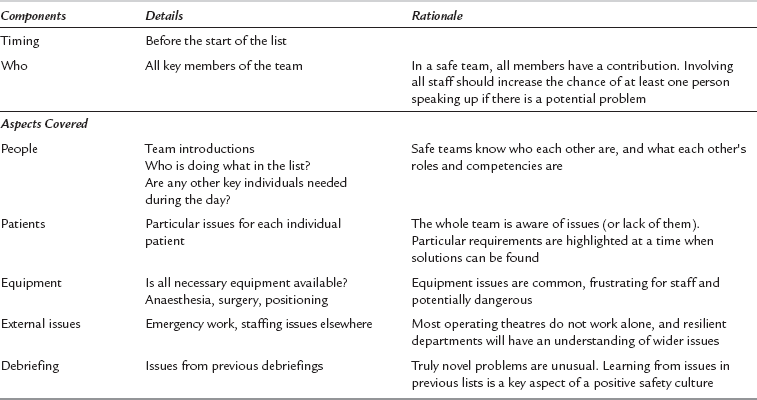

Debriefings are a complement to the briefing process (Table 44.2). The concept is that the team reviews its performance each day – did it match the plans made at the start of the day? Good practice is reinforced and areas of improvement are discussed constructively. Information from debriefings should be shared with other team members and necessary actions should be completed and fed back to the team.

Situational Awareness

MEASURING SAFETY AND QUALITY

Safety Culture

AHRQ’s (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture

AHRQ’s (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture

Safety attitudes questionnaire

Safety attitudes questionnaire

Measuring Quality

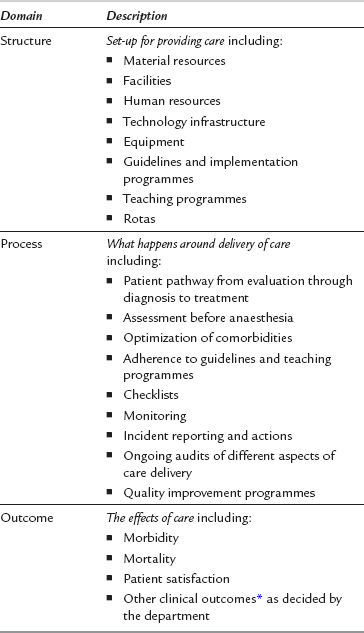

A comprehensive measurement of quality would assess, and somehow measure, all the individual components of the quality matrix, i.e. safety, clinical effectiveness, patient experience, timeliness, efficiency and equity. In 1988, Avedis Donabedian introduced a framework for assessing quality in healthcare (Table 44.3). This framework is based on three core domains – structure, processes and outcomes.

It is important to understand that the three domains of measuring quality are interdependent. Good processes depend upon good structures, and they often lead to good outcomes. Consequently, assessment of only one domain (e.g. outcome – mortality) cannot assess quality, or serve to improve it. It becomes useful only when this assessment is combined with finding the gaps in structure (e.g. staff shortage) and/or processes (e.g. non-adherence to guidelines). At present, much is being written and discussed about what should be measured to assess the existing quality of care, and any improvements. The Donabedian framework can be used to address each component of quality as shown in Table 44.4.

Clinical Outcomes: Real or Surrogate

The real outcomes may depend on many factors including the patient’s pre-existing condition, population dynamics, surgical factors and individual reactions (e.g. unknown allergies), which may not necessarily indicate quality of care per se.

The real outcomes may depend on many factors including the patient’s pre-existing condition, population dynamics, surgical factors and individual reactions (e.g. unknown allergies), which may not necessarily indicate quality of care per se.

Direct anaesthesia-related mortality is rare, and serious morbidity infrequent. Consequently, measuring anaesthesia-related mortality and morbidity can only be very crude measures and may not provide enough data to monitor quality on a regular basis (monthly or quarterly).

Direct anaesthesia-related mortality is rare, and serious morbidity infrequent. Consequently, measuring anaesthesia-related mortality and morbidity can only be very crude measures and may not provide enough data to monitor quality on a regular basis (monthly or quarterly).

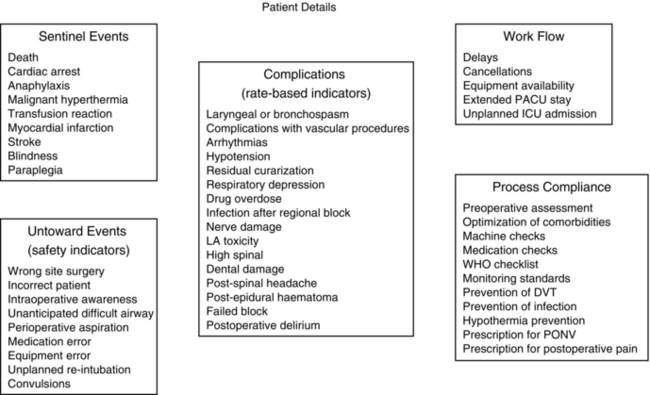

Quality Indicators at Individual Patient Level

There is very little guidance as to what individual departments of anaesthesia should be measuring on a routine basis in every patient as part of their quality improvement programme. A framework is suggested here, which includes sentinel events, adverse events, rate-based outcome indicators and work process quality indicators (Fig. 44.2). Some of these data would be available from existing hospital IT systems; others may have to be collected as part of on-going audit or service evaluation programmes. The framework can also be used by individual anaesthetists to maintain a record of their own activity and quality of care. At the departmental level this can inform, on a continuous basis, the quality of care which the department is providing to its patients, and the effect of any quality improvement programme.

Quality Assessment at Departmental Level

At the departmental level, in addition to the outcome data at individual patient level (Fig. 44.2), quality measures would include structural and process attributes as summarized in Tables 44.3 and 44.4.

Quality Improvement Tools

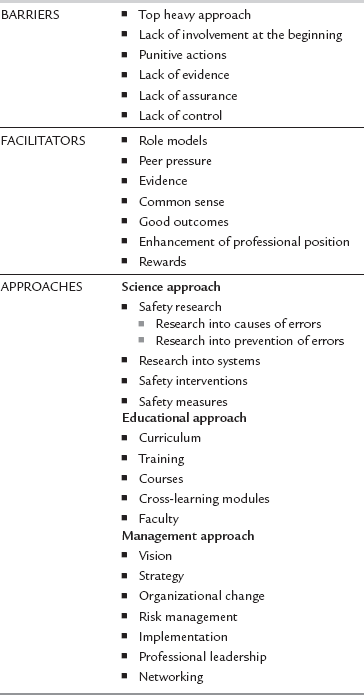

Requirements for Quality Improvement: The challenge for a department, in addition to collecting all the data at an individual patient level, is to analyse the data systematically, disseminate the findings as widely as possible and identify learning outcomes and areas for improvement. In order to improve quality, departments will be required to develop interventions targeted at areas for improvement, implement them, and monitor progress and the impact of implementation on outcome measures. For a successful quality improvement programme, it is important for departments to invest in creating leaders and teams. It is vital for the leaders to address and improve the prevailing quality culture within the department. Continuing education and programmes to raise awareness are extremely important. Embedding a culture of incident reporting and learning is vital. Morbidity and mortality meetings and other network opportunities at which all quality issues can be aired and discussed without fear of a punitive outcome are absolutely essential for embedding quality consciousness.

Recent experience with implementing the WHO checklist has presented many challenges and has provided insight into what is required for successful implementation of a quality improvement intervention. Clear demonstration of success of the interventions, with the help of data and its rigorous analysis, is vital for motivating staff and increasing their belief in such interventions. Whilst all failures should be used as learning experiences, the successes must be celebrated. Barriers, facilitators and approaches in engaging staff into quality improvement are summarized in Table 44.5.

Checklists: Although they existed earlier, the modern era of the safety checklist is generally attributed to the crash of the newly designed Model 299 Boeing bomber in 1935. The cause of the crash was straightforward – the elevator lock had been left on. However, two extremely important facts emerged from the investigation. First, the pilot was an extremely experienced and competent pilot. Second, taking the elevator lock off was not an unusual requirement. The pilot would do this normally, but on this occasion, presumably due to distraction by other things, he forgot. The response of pilots was to create a process which ensured that simple things did not get missed, regardless of the situation.

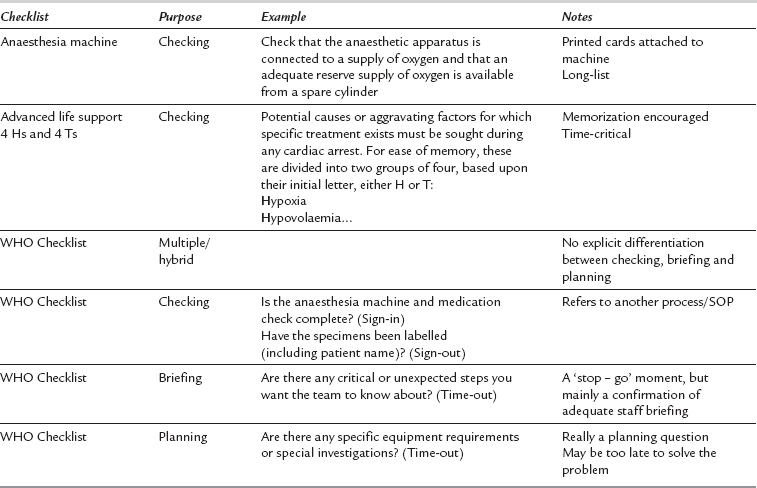

WHO Checklist: The WHO checklist is a hybrid checklist. It involves elements of planning, briefing and checking (Table 44.6). The components on the checklist match the WHO Safe Surgery Saves Lives objectives believed to be fundamental to improving outcomes following surgery (Table 44.7).

TABLE 44.7

WHO Safe Surgery Saves Lives Objectives

| Objective | |

| 1. | The team will operate on the correct patient at the correct site. |

| 2. | The team will use methods known to prevent harm from anaesthetic administration, while protecting the patient from pain. |

| 3. | The team will recognize and effectively prepare for life-threatening loss of airway or respiratory function. |

| 4. | The team will recognize and effectively prepare for risk of high blood loss. |

| 5. | The team will avoid inducing an allergic or adverse drug reaction known to be a significant risk to the patient. |

| 6. | The team will consistently use methods known to minimize the risk of surgical site infection. |

| 7. | The team will prevent inadvertent retention of swabs or instruments in surgical wounds. |

| 8. | The team will secure and accurately identify all surgical specimens. |

| 9. | The team will effectively communicate and exchange critical patient information for the safe conduct of the operation. |

| 10. | Hospitals and public health systems will establish routine surveillance of surgical capacity, volume and results. |

DESIGNING PROBLEMS OUT OF THE SYSTEM

Learning from Incidents

There are several key components to learning from incidents and near-misses:

Acknowledging and Recording that they Happen: Unfortunately, there is still a common perception of punitive responses to incidents which, in part, leads to significant under-reporting. A cultural failure to recognize the importance of incidents and near-misses may result in some organizations simply not reporting incidents which have occurred. There are structural barriers to reporting in many organizations, with cumbersome paper or electronic systems.

Appropriate Analysis of Incidents

Feedback to Relevant Staff: A common reason why staff choose not to fill in incident reports is that they feel nothing changes anyway. Departments and organizations have to develop processes which allow staff to receive meaningful feedback about incidents without being swamped by an overload of information.

Organizational Memory: Most errors within healthcare have happened before. Sadly, healthcare has too often forgotten the lessons it learnt last time. This happens particularly when events are separated widely in time or geography. National organizations such as the Colleges and Associations have a key role to play in ensuring that the lessons learnt in previous times are passed on to successive generations of anaesthetists.

Models for Implementing Quality Improvement Programmes

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA): The Institute of Healthcare Improvement has used this method widely for rapid cyclical improvements. At the beginning of the cycle, the nature of the problem is determined. The next stage is that of planning for a specific targeted change. The change is then implemented, and data and information collected to study the impact. The last part of the cycle involves taking action by either implementing the change or starting the process again. The overall improvement may require many small and frequent PDSA cycles rather than one big and slow cycle.

Six Sigma: The main aim of this model is to improve processes to minimize or eliminate waste. The improvement is measured by assessing process capability. Before an intervention is designed and undertaken, baseline assessment is carried out to establish how a process is performing. This is done by observing the process and counting the defects or areas of improvement. The defect rate per million is then calculated to a sigma metric using statistical tools. Potential solutions for improvement are then designed and piloted. The measurements of the sigma metric are undertaken again to quantify improvement in the process. This method is useful mainly for process improvements and the methodology can be undertaken on a regular basis while efforts to improve processes with multiple interventions are being undertaken in an organization.

Lean Production System: This system overlaps with the six sigma methodology, and is similarly aimed at minimizing waste and improving efficiency by simplifying overcomplicated processes and avoiding duplications and rework. The front-line staff are involved throughout the process and the problems are rigorously tracked as the staff experiment with potential improvements. The lean system is driven by the identification of customer needs. With a focus on the needs of the customers, any activity which does not add value (waste) is then removed. Thus, the value-added activities are maximized, waste is removed and efficiency savings are made.

Root Cause Analysis: This methodology is commonly used for improvements at organizational and departmental level. The analysis is triggered by an adverse event. A retrospective systematic analysis is undertaken to tease out the underlying factors which may have caused and/or contributed to the generation of the event. The spirit of analysis is the belief that systems, rather than individual incompetence, are likely to be the root cause of most problems. With an overarching systems approach to understanding the problem in a non-punitive manner, a trained multidisciplinary team investigates the event to ask a series of questions: what happened, why did it happen, what factors caused it, what contributed to it and what system improvements could prevent it. The team then makes recommendations for changes in system improvements.

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis: The methodology and the underlying principles of this analysis are similar to root cause analysis. The difference is that failure modes and effects analysis is undertaken proactively. The processes and systems are observed and analysed for any potential failure by a multidisciplinary team. The team then evaluates a number of options which can mitigate potential failures, and finally makes recommendations for systems improvements.

Donabedian, A. Evaluating quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 1966;44:166–206.

Leape, L.L. Errors in medicine. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2009;404:2–5.

Staender, S., Mellin-Oslen, J., Pelosi, P., Van Aken, H. Safety in anaesthesia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2011;25:109–304.

Varkey, P., Peller, K., Resar, R.K. Basics of quality improvement in healthcare. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007;82:735–739.

Vincent, C. Patient safety, second ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.