3 Quality and Safety

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• describe the contribution that evidence-based nursing can make to critical care nursing practice.

• identify the steps in developing clinical practice guidelines.

• explain the role care bundles and checklists have in promoting quality and safety in critical care nursing practice.

• discuss rapid response systems used to respond to deteriorating patients.

• describe the use of information and communication technologies in critical care.

• identify techniques used to understand situations that place patients at risk of adverse events in critical care.

• identify strategies to improve the safety culture in critical care.

Introduction

Today’s critical care units are both busy and complex, where nurses, doctors and other health professionals use their knowledge, skills and technology to provide patient care. In fact, this complexity makes errors a common occurrence; one large international study in 205 Intensive Care Units (ICU) showed that 39 serious adverse events occurred per 100 patient days.1 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the USA defines quality of health care as ‘the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge’.2 Critical care nurses are well known for their skills in patient assessment. In fact, this ongoing surveillance of patient condition means that nurses are ideally positioned to prevent, discover and correct medical errors.3 Thus, nurses play a key role in improving quality and safety in health care. This chapter provides a review of quality and safety in critical care. First, an overview of evidence-based nursing and clinical practice guidelines is given to provide a foundation to consider quality and safety. Next, quality and quality monitoring is considered. Included in this section are the topics of care bundles, checklists, rapid response systems and information and communication technologies. Finally patient safety, including safety culture is described. In Chapter 2 we addressed risk management, clinical governance and the role of clinical leaders and managers in delivering critical care services; this information is complementary to what will be discussed in Chapter 3.

Evidence-Based Nursing

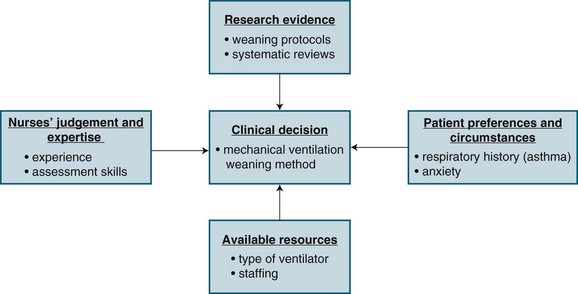

Evidence-based nursing (EBN) is the ‘Application of valid, relevant, research-based information in nurse decision-making.’4 Research evidence, however, is only one of four considerations in making a clinical decision. Three other considerations include: (1) knowledge of patients’ conditions (i.e. preferences and symptoms); (2) the nurses’ clinical expertise and judgment; and (3) the context in which the decision is taking place (i.e. setting, resources). Figure 3.1 provides a schematic representation of EBN, using an example of a decision about weaning a patient from a mechanical ventilator.

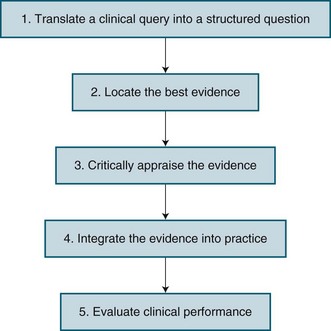

EBN has emerged as a way to improve nursing practice by considering the care that nurses give to patients, and whether this care results in the best possible outcomes for patients. It has been viewed as both an attitude and a process. As an attitude, it is a way of approaching practice that is critical and questioning. As a process, a number of steps in EBN have been described. Figure 3.2 identifies these steps, with more details about each step being provided below.

Translate a Clinical Query into a Structured Question

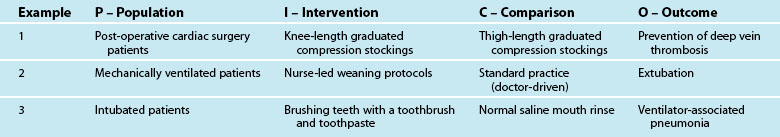

In situations where nurses have to make clinical decisions, it is important for them to carefully consider the issue or problem they are facing as it influences what research evidence should be used to make decisions. Thus, the first step in the EBN process is translating a clinical query into a well-defined, answerable, structured question. A well recognised approach is the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome format, more often referred to as PICO. The Population reflects the patient group or clinical scenario of concern. The Intervention is one option for the particular nursing practice. The Comparison is the current practice, or the second option for practice. Finally, the Outcome is the effect that the nurse is hoping to achieve, which should reflect a patient outcome. Table 3.1 provides three examples of PICO questions relevant to critical care nursing.

Critically Appraise the Evidence

Once the various sources of evidence have been retrieved, they are then assessed for their quality and relevance to the clinical question. In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)5 has described strategies to assess research evidence on the effectiveness of interventions. It provides a useful framework to consider research evidence for improving nursing interventions, and identifies three questions to ask regarding potential interventions:

This first question regarding the real effect relates to the strength of the research that has been conducted. The strength of the research has three dimensions: level of evidence, quality of the individual studies, and their statistical precision (denoted by P values or confidence intervals). Although there are a number of different evidence hierarchies (e.g. see Jennings & Loan, 2001),6 the framework used by the NHMRC5 is displayed in Table 3.2.

TABLE 3.2 NHMRC’s level of evidence5 designation for levels of evidence in the studies of effectiveness

| Level of evidence | Study design |

|---|---|

| I | Evidence obtained from a systematic review of all relevant randomised controlled studies |

| II | Evidence obtained from at least one properly designed randomised controlled trial |

| III-1 | Evidence obtained from well-designed pseudorandomised controlled trials (alternative allocation or some other method) |

| III-2 | Evidence obtained from comparative studies (including systematic reviews of such studies), with concurrent controls and allocation not randomised, cohort studies, case-control studies, or interrupted time series with a control group |

| III-3 | Evidence obtained from comparative studies with historical controls, two or more single-arm studies, or interrupted time series without a parallel control group |

| IV | Evidence obtained from case series, either post-test or pre-test/post-test |

The third question conveys the notion that potential benefits or outcomes of the intervention must be both important to the patient, and be able to be replicated in other settings. The NHMRC5 identifies three types of outcome: surrogate, clinical, and patient-relevant (which are not mutually exclusive) (see Table 3.3). Surrogate outcomes are often used in critical care where measurement of the actual physiological change (e.g. oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood) is replaced by a more accessible, and equally acceptable, parameter (e.g. oxygen saturation). Clinical outcomes are those of direct relevance to clinical practice, and patient-relevant outcomes are those likely to be articulated as significant by the patient/carer. When assessing research evidence, the type of outcome used in the research should be considered. Assessing the evidence results in an understanding of its quality of evidence for a particular nursing practice.

| Outcome | Definition | ICU example |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate | Some physical sign or measurement substituted for a clinically meaningful outcome |

Clinical Practice Guidelines

The development and use of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) is one strategy to implement EBN. CPGs are statements about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances that assist practitioners in their day-to-day practice.7 They are systematically developed to assist clinicians, consumers and policy makers in healthcare decisions and provide critical summaries of available evidence on a particular topic.8 Other terms that are often used synonymously with CPGs include protocols and algorithms.

There are a number of benefits of using CPGs. They are seen to be central to quality patient care because, in essence, they standardise care.9 They can guide decisions and can be used to both justify and legitimise activities and practices.9 However, limitations have also been identified. Poorly developed guidelines may not improve care and may actually result in substandard care9. In the critical care area, the Intensive Care Coordination and Monitoring Unit of New South Wales Department of Health has led the development of CPGs associated with six common nursing interventions: (1) Eye care; (2) Oral care; (3) Suctioning a tracheal tube; (4) Endotracheal tube stabilisation; (5) Central line care; and (6) Arterial line care.10 Clinical audits are often used to establish the need to develop new protocols at the local unit level. Clinical audits generally involve chart reviews, but may also use direct observation or surveys of practice. Clinical audits often establish variation in practice without adequate justification.

Developing, Implementing and Evaluating Clinical Practice Guidelines

A number of steps are undertaken when developing clinical practice guidelines. Table 3.4 provides an overview of these steps, which has been adapted from Miller and Kearney’s work.9

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Find the evidence | After deciding on what is considered evidence, databases such as CINAHL and Medline must be searched to find relevant studies and expert opinions. |

| Evaluate the evidence | Relevant studies and expert opinion papers must be critically appraised for their strengths and weaknesses. This may or may not incorporate a systematic review. |

| Synthesise the evidence | General summary statements about the state of knowledge on a particular topic are developed. |

| Design the guidelines | Written summaries, algorithms and/or summary sheets will be developed that include statements about appropriate healthcare practices and their rationale. |

| Appraise the guidelines | Validity, reliability, clinical applicability, flexibility and clarity are some criteria that can be used to assess the guidelines. |

| Disseminate and implement the guidelines | Specific strategies such as seminars and patient chart reminders must be developed to increase awareness, acceptance and implementation of the guidelines. |

| Review and reassess the guidelines | Clinical audits and research may be used to regularly evaluate the impact the guidelines have had on patient care and outcomes. |

Based on the assessment of the CPG, revisions may be required. Next, strategies for disseminating and implementing the guidelines should be developed. Importantly, simply publishing and circulating CPGs will have a limited impact on clinical practice, so specific activities must be undertaken to promote CPG adherence. The following seven strategies have been shown to be moderately effective in promoting guideline adherence: (1) interactive small group sessions; (2) educational outreach visits; (3) reminders; (4) computerised decision support; (5) introduction of computers in practice; (6) mass media campaigns; and (7) combined interventions.7 Finally, a process for regularly evaluating and updating the guidelines must be developed, which may involve quality improvement activities or clinical research. In summary, by developing, using and evaluating clinical practice guidelines, nurses may improve patient care and outcomes. Additionally, use of CPGs should ensure that nursing practice is based on the best available evidence.

Quality and Safety Monitoring

This section discusses unit-level measures used to evaluate the quality and safety of care for critically ill patients. Quality and safety in healthcare is commonly described in terms of Donabedian’s approach11 with three major domains:

1. Patient outcomes – the results of care in terms of recovery, restoration of function and/or survival (e.g. mortality, health-related quality of life).

2. Process – the practices involved in the delivery of care (e.g. pressure ulcer prevention strategies).

3. Structure – the way the healthcare setting and/or system is organised to deliver care (e.g. staffing, beds, equipment).

More recently, a fourth domain of culture or context has been suggested specifically for patient safety models to evaluate the context in which care is delivered.12 The contemporary model for healthcare improvement recognises that the resources (structure) and activities carried out (processes) must be addressed within a given context (culture) to improve the quality of care (outcome). The overall aim of quality improvement (QI) is to provide safe, effective, patient-centred, timely, efficient and equitable health care.13 QI activities identify and address gaps between knowledge and practice. Importantly, these activities need to reflect the most recent and robust clinical evidence to improve patient care and reduce harm. The most common approach used for rapid improvement in healthcare is the plan–do–study–act (PDSA)14 method where four essential steps are carried out in a continuous fashion to ensure processes are continually improved:

1. Plan – identify a goal, specify aims and objectives to improving an area of clinical practice, and how that might be achieved (i.e. how to test the intervention).

2. Do – implement the plan of action, collect relevant information that will inform whether the intervention was successful and in what way, taking note of problems and unexpected observations that arise.

3. Study – the results of the intervention, particularly its impact on practice improvement, noting any strengths and limitations of the intervention.

4. Act – determine whether the intervention should be adopted, abandoned or adapted for further rapid cycle testing recommencing at the Plan phase.

A variety of specific activities have been used in the ICU setting to translate findings from the literature to improve clinical practice.15 Quality monitoring includes measurement of, and response to, the incidence and patterns of adverse events (AEs). Adverse events occur in up to 17% of all hospital admissions,13 and cost the Australian healthcare system an estimated $2 billion per year.16 About 18,000 hospital deaths per year are associated with AEs13 and generally occur as a result of system errors. Half the AEs were deemed preventable with such strategies as improved protocols, better-quality monitoring, enhanced training and opportunities to consult with specialists or peers on clinical decisions.17 Studies have identified specific contributing factors for adverse events related to patient airway18 and intra-hospital transports.19

A number of methods for reporting AE such as direct observation chart audit and self or facilitated reporting can be used; each has its strengths and limitations. Trained observers report more unintended events but this method is expensive, labour intensive and vulnerable to the Hawthorne effect.20 Both chart audits and incident reporting only reflect what is charted or reported, but even when chart audit, incident reporting, general practitioner reporting and external sources, such as coronial review, are used together, some adverse events will be missed.21 Importantly, self or facilitated reporting, such as the Australian Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS)22,23 are routinely used surveillance methods in many countries.

Medication administration is the most common intervention in health care, but the medication management process in the acute hospital setting is complex, and creates risk for patients. As a result, medication-related events are the commonest AE for hospitalised patients.24 Adverse drug events (ADEs) are common in Australian hospitals, with preventable, high-impact events involving anticoagulants, anti-inflammatories and cardiovascular drugs (over 50% of ADEs), as well as antineoplastics, opioids, steroids and antibiotics (commonly used in critical care units).17 Events are clinically significant in 20% of cases.17 A number of strategies have been instituted in Australia under the auspices of the National Medicines Policy, including the quality use of medicines (QUM) framework. There, however, remains a lack of consensus on how to measure medication safety25 – either by error or adverse event – where:

The actual incidence of both measures is higher than what is reported.17,26 Fortunately, most healthcare errors do not result in patient harm because of safety-net processes.24 Despite this, it has been estimated that one potentially serious intravenous drug error occurs every day in a 400-bed hospital.27 Approximately 5% of medication errors relate to infusion pumps. These pumps are used to administer high-impact medications, such as inotropes, heparin or antineoplastics.28 It is therefore important to evaluate interventions that can reduce the incidence and impact of adverse intravenous drug events, particularly in critical care settings.29,30 Recent evidence suggests that nurses who are interrupted whilst administering medications may have an increased risk of making medication errors,31 prompting calls for all healthcare workers to make concerted efforts to reduce interruptions to clinical tasks.32 Other activities examining quality of care include the analysis of incident reports such as the Australian Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS),22,23 Quality in Australian Health Care Study (QAHCS)17 and the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) indicators.33 Current ACHS indicators for intensive care include:

• inability to admit a patient to the ICU due to inadequate resources

• elective surgery deferred or cancelled due to lack of ICU/HDU bed

• patients transferred to another facility due to unavailability of an ICU bed

• delays on discharging patients from the ICU of more than 12 hours

• patients discharged from the ICU after hours (i.e. between 6pm and 6am)

• recognising and responding to clinical deterioration within 72 hours of being discharged from ICU

• patients being treated appropriately for VTE prophylaxis within 24 hours of admission to the ICU

• ICU central line-associated bacteraemia rates

• use of patient assessment systems (participation in national databases and surveys).33

Similar activities are evident internationally, where concepts of ‘safety science’ (error reduction and recovery) are being applied to critical care practice.29,34–36 Process indicators of quality care have been developed, including care related to the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and central venous catheter management. Table 3.5 outlines process indicators with good clinical evidence and/or strong recommendations for use by professional bodies, such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in the USA.

| Process | Process indicator |

|---|---|

| 1. Central venous catheter management | Maximum sterile barriers Real-time ultrasound guidance during insertion Antibiotic-impregnated catheter |

| 2. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia | Elevated head of bed Continuous aspiration of subglottic secretions Stress ulcer prophylaxis |

| 3. Reducing mechanical ventilation | Low tidal volumes for acute respiratory distress syndrome Weaning protocols Sedation protocols Appropriate use of analgesia and sedation |

| 4. Pressure ulcer prevention | Use of pressure-relieving materials |

A range of clinical support tools have been developed and are used to measure compliance with these best practice clinical standards. Daily goals forms, for example, have been used to aid communication between clinicians during and after multidisciplinary ward rounds and ensure that all staff are aware of what care the patient should be receiving and what the clinical plan is.37,38 A popular mnemonic developed for use by ICU clinicians during patient assessment is the ‘FASTHUG’ which stands for Feeding, Analgesia, Sedation, Thromboembolism prophylaxis, Head-of-bed elevation, stress ulcer prevention and Glucose management.39 Along with care bundles and checklists (detailed below) these tools facilitate standardised care and improve communication between clinicians.38

Care Bundles

An evolving QI approach to the optimal use of best practice guidelines at the bedside is the development of ‘care bundles’. A care bundle is a set of evidence-based interventions or processes of care, applied to selected patients. A number of bundles have been developed for critical care by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in the USA (see Table 3.6).

| Bundle name | Aim | Bundle components |

|---|---|---|

| Central line | Prevent central-line associated bacteraemia |

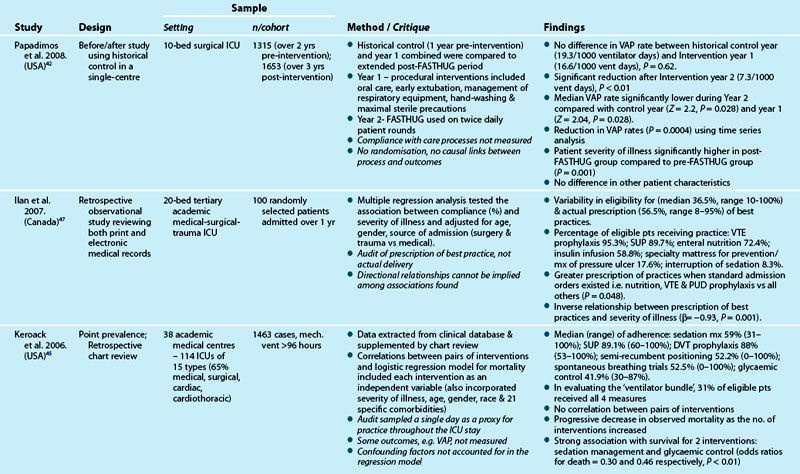

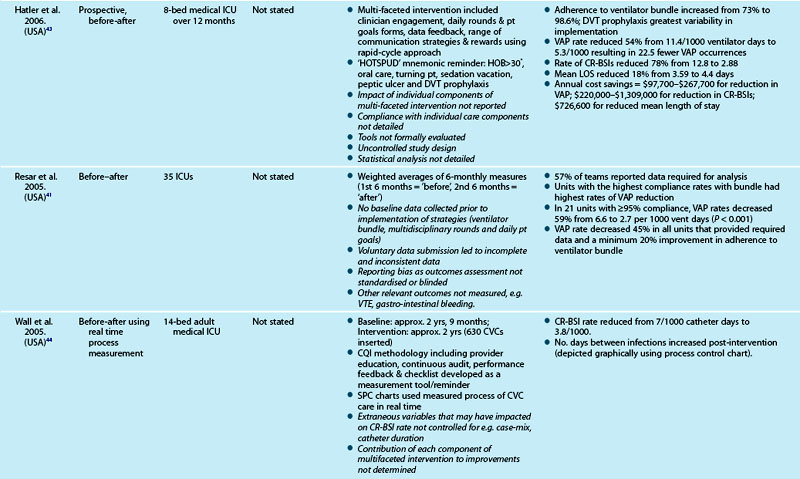

Table 3.7 outlines studies examining the process of care delivery in critical care units, including those where care bundles were implemented and evaluated. Increased bundle compliance was associated with decreased ICU length of stay (LOS), reduced ventilator days and increased ICU patient throughput,40 and decreased rates of ventilator-associated pneumonia.41 Other quality improvement studies targeted similar processes of care without taking the bundled approach. A range of measures demonstrated improved outcomes:

• decreased VAP,42,43 catheter-related bloodstream infection (CR-BSI) rates and LOS43

• increased days between CR-BSIs44

• decreased hospital mortality as the number of process interventions increased45

• reduction in severity-adjusted total hospital costs related to improvements in process measures of care, including glucose control, use of enteral feeding and appropriate sedation.46

Although studies revealed improvements in both processes and outcomes, variation in levels of compliance with process measures were also reported (see Table 3.7 for detail). One study47 revealed the more unwell the patient was, the less likely they were to have received practices they were eligible for.

Checklists

Checklists have the potential to prevent omissions in care by serving as reminders to healthcare providers for the delivery of appropriate quality care for every patient, every time, in complex clinical environments. A checklist typically contains a list of action items or criteria arranged in a systematic way, allowing the person completing it to record the presence or absence of individual items to ascertain that all are considered or completed.48

• assisted in improving the understanding patient therapy goals49

• improved compliance with safety standards50

• detected patient safety errors51 and omissions in care52,53

• improved compliance with evidence-based care44,50,54,55

• proved useful in preparing for a procedure56

• were not time consuming52–53 or labour intensive52

• when developed in conjunction with clinicians, produce a valid and reliable tool that is consistently used52

• enabled collection of real-time process measures to assist in the immediate identification of anomalies.44

Three studies suggested that checklists also contributed to improved outcomes: (1) reduced LOS, ventilator days, unit mortality;49 (2) reduced catheter-related bloodstream infections;44 and (3) reduced mean monthly rates of VAP.54 However, the lack of methodological rigour in these studies prevents inferring causal links between checklist use and improved outcomes.57

Information and Communication Technologies

Health departments continue to develop systems and processes that will result in a complete electronic medical record. In Australia, a national e-health strategy has been established,58 with the National E-Health Transition Authority (NEHTA), a company established by the Australian, State and Territory governments, assigned responsibility for establishing the foundations (including the development of standards) for e-health across the Australian health sector.59 The ultimate goal is an individual electronic health record system designed to provide ‘a consolidated and summarized record of an individual’s health information for consumers to access and for use as a mechanism for improving care coordination between care provider teams’.58 (p.13)

In combination with these initiatives, information and communications technologies (ICT) are also expanding into clinical practice.60 Critical care in particular is at the forefront of these developments, with bedside clinical information systems, order-entry strategies, decision support, handheld technologies and telehealth initiatives continuing to evolve and influence practice. This section examines the current and future impact that these technologies will have on patient care and safety, and on clinician workflows and practices, as clinical information fully assimilates with evidence-based practice and clinical decision support systems.

Clinical Information Systems

A clinical information system (CIS) enables improved data collection, storage, retrieval and reporting of patient-based information, and can facilitate unit-based outcomes research and quality improvement activities.61 Computerisation of monitoring and therapeutic activities for critically ill patients began in the 1960s, and has now evolved to encompass all aspects of patient care such as cardiorespiratory monitoring, mechanical ventilation, fluid and medication delivery, imaging and results of diagnostic testing.62,63 Patient-based bedside CIS offers increasingly sophisticated functionality and device interfaces,64 enabling real-time data capture, trending and reporting,62 and linkage to relational databases.65,66

The introduction of intravenous ‘smart pump’ technology is one application aimed at reducing adverse drug events and improving patient care by supporting evidence-based guidelines for medication management.67 The operator-error prevention software is based on a device-based drug library with institution-established concentrations/dosage limits incorporated in the function of the pump. Resulting software functions include clinician alerts (for keystroke errors)28 and transaction log data (post-incident analysis).68 Medication errors and adverse drug events can be detected by this software, but further technological and nursing behavioural factors must be addressed before a measurable impact on serious adverse drug errors can be achieved.69

The proportion of ICUs in Australia and New Zealand using a CIS is not known, while the estimate for units using electronic charting in North America is 10–15%.64,70 Early generation systems held promise of improved efficiencies but did not demonstrate actual decreases in nursing workload or activity patterns, including in one Australian site.71 Current third-generation systems (Windows NT operating system [or equivalent] with relational databases and enhanced graphic displays and user interfaces)63 have reduced documentation time (52 minutes per 8-hour shift) and increased the proportion of time on direct care activities.72 Despite these positive findings, it is noted that a CIS would not enable a reduction in nursing staff; on the contrary, at least a half-time nursing position is required to administer the system.72 An Australian study demonstrated significant reductions in medication and intravenous fluid errors and the incidence of pressure areas, and improved variance between ventilator orders and settings, after implementation of a CIS.73 A sample of nursing staff perceived that the CIS also increased time on patient care and decreased documentation time, while staffing recruitment and retention rates improved.73 Findings that critical care nurses are accepting of new technologies were previously noted.74

Other issues also need consideration. Accuracy of data (correctness and completeness of the data set) from both manual and automated inputs to the information system requires evaluation. While automated entry eliminates transcription errors from other data sources,75 the use of ‘carry-over’ data to new fields, sampling frequency, and clinician acceptance of monitor-generated data can erroneously affect data accuracy (e.g. damped pulmonary artery waveform not checked, with erroneously low readings documented).61 In addition to errors related to entering and retrieving information, errors can also arise if systems are not designed to enhance communication between healthcare workers and facilitate coordination of work processes.76 Further, ‘clinical alert’ functions can lack the specificity for detecting clinically important events70 and may compromise patient safety when used excessively in clinical settings with one study demonstrating 49–96% of drug safety alerts were overridden by clinicians.77

To tackle these and other limitations, future systems will provide wireless capabilities, remote access, ‘smart’ alerts, handwriting recognition, clinician-configured forms, flowcharts and reports using standardised data structures and terminology. This level of functionality will enable decision support with online evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, real-time clinical alerts, and online patient historical information via a complete electronic medical record.78

Computerised Order Entry and Decision Support

Computerised physician (or provider) order entry (CPOE) is viewed as an important innovation in reducing medical errors, through minimising transcribing errors,25 triggering alerts for adverse drug interactions and facilitating the adoption of evidence-based clinical guidelines.70,73,79,80

Computerised order entry is used for medication and intravenous fluid prescribing, diagnostic test ordering and results management, and mechanical ventilation or other treatment orders.79,81 Implementation of CPOE and related clinical decision support systems (CDSS) have demonstrated significant reductions in medication errors79 and redundant or unnecessary order requests,82–84 and improved compliance with practice guidelines.85–86 Clinical decision support systems interface with hospital databases to retrieve patient-specific and other relevant clinical data and to generate recommended actions.87 Importantly, clinical decision making at the bedside can be enhanced by providing clinicians with a readily available tool that incorporates relevant clinical information and evidence-based medicine.88 Clinician alerts (e.g. allergies or interaction effects) or prompts (e.g. to check coagulation when prescribing warfarin) can be generated. A number of studies have demonstrated improved delivery of patient care after the introduction of such reminders.89–91 As with CIS implementation, examination of clinician workflow and care delivery patterns81 and detailed planning is required for successful implementation of a CPOE process.92 In particular, order decryption, prioritisation and translation steps within the medication or treatment order process require review to minimise potential errors.92 Additional developments involving wireless communication, personal digital assistants and closed-loop delivery systems will improve the efficiency, effectiveness and adoption of this innovation in clinical practice.79 Closed-loop delivery adjusts drug or fluid delivery based on active feedback from the target parameter (e.g. inotropic dosages adjusted to a range for mean arterial pressure).

Handheld Technologies

Wireless applications enable both clinical access and portability and mobility within a critical care environment at the point of care. Clinical uses for personal digital assistant (PDA) and Smartphone technologies continue to evolve at a rapid pace.93 These handheld computers use operating systems and pen-like styluses that enable touch-screen functionality, handwriting recognition, and synchronisation with other hospital-based computer systems. An increasing array of clinical applications and content are available for downloading to PDAs, including drug reference information (e.g. MIMS on PDA), clinical guidelines, medical calculators and internet-based literature searches.93–95 PDA use has been reported as a helpful nursing education tool,96,97 with nursing students reporting specific benefits of PDA use such as having access to readily available data, validation of thinking processes and facilitation of care plan re-evaluation.97 In critical care, PDAs have been used to document clinical activities, such as logging critical care procedures, which was demonstrated as feasible and useful, although adoption and user acceptance was not uniform.98 They have also been used to deliver point-of-care decision support to improve antibiotic selection99 and prescribing,84 and an interactive weaning protocol that assisted care providers wean patients from mechanical ventilation more efficiently when compared with the use of a paper-based weaning protocol.100

The benefits of this mobile computing also create concerns, particularly regarding confidentiality of patient information. Health services therefore need policies for managing handheld devices, including password protection, data encryption, authenticated synchronisation and physical security.95 In particular, wireless applications require appropriate standards for data security (e.g. wireless-fidelity protected access 2 [WPA2] compliance).78 As these issues are addressed, these technologies will form an integral component of routine clinical practice in critical care.

Telehealth Initiatives

Remote critical care management (eICU) using telemedicine/telehealth technologies is expanding as the necessary high bandwidths for transmitting large amounts of data and digital imagery become available between partner units or hospitals. Videoconferencing functions enable direct visualisation and communication of patients and on-site staff with the ‘virtual’ critical care clinician or team. Review of real-time physiological data, patient flowcharts and other documents (e.g. electrocardiograms, laboratory results) or images (e.g. radiographs) provide a comprehensive data set for patient assessment and management.101

This technology-enabled remote care initiative is of particular value for critical care units where no or limited on-site intensivist resources are available. Despite various methodological limitations,102 several studies using ‘before and after’ comparisons have indicated improved outcomes such as decreases in severity-adjusted hospital mortality, incidence of ICU complications, ICU length of stay, and ICU costs.101,103,104 One study demonstrated improved outcomes for neurological ICU patients through the use of a robotic tele-ICU system that made rounds in response to nurse paging.104 More recent studies, however, have not found improvement in patient outcomes as a result of telemedicine technology,105–107 highlighting the complex nature of these initiatives and the difficulties evaluating them. One local study instead observed improvements in patient management (i.e. increased discharges and decreased transfers) for moderate trauma patients upon implementation of a virtual critical care unit that linked a district hospital ED with a metropolitan tertiary hospital ED. Further studies that include detailed descriptions of system implementation are required in determining the most effective elements of this technology in critical care settings.102,108

In addition to remote patient assessment and management, telecommunications have been used to deliver continuing education to rural healthcare professionals for many years via audio, video and computer.109 More recently, distance education has been delivered via web-based courses accessed over the internet.110 For example, a web-based educational tool was used to provide information about the classification of pressure ulcers and the differentiation between pressure ulcers and moisture lesions to both student and qualified nurses.111 The potential use of web logs or ‘blogs’,112 online communities and virtual preceptorships110 in nursing education has also been discussed. Continuing professional development (CPD) opportunities are also provided on-line, for example AusmedOnline contains a range of resources and learning activities that count towards CPD for registration requirements. However, more work is required to determine how successful these technological advances are on educational outcomes.113

Patient Safety

The signing of the Declaration of Vienna in 2009114 (Appendix A4) committed critical care organisations around the world, including the World Federation of Critical Care Nurses, to patient safety.114 Patient safety is viewed as a crucial component of quality.115 Over the years, numerous definitions of patient safety have emerged in the literature. The Institute Of Medicine116 described it as the prevention of harm, however, more recently, the European Agency, Safety Improvement for Patients in Europe,117 asserted it was about identifying, analysing and minimising patient risk. This latter description is appealing as it leads us to consider the degree of risk situations pose for patient harm and targeting those that are either high risk or frequent in occurrence.

Three techniques used to understand patient risk are analysing reports of adverse events, root cause analyses and failure mode and effect analysis. Recent research on adverse events in critical care has helped to both better understand patient risks and target improvement activities. For example, medications, indwelling lines and equipment failure were the three most frequent types of adverse events in a study of 205 Intensive Care Units world-wide.1 Focusing on analysing the narratives written about adverse events is viewed as an important way to learn from errors. Root cause analyses is a structured process generally used to analyse catastrophic or sentinel events.118,119 Learning from both incident reporting such as AIMS and root cause analyses is based on the premise that the information they contain is of sufficient quality to allow accurate analysis, interpretation and detection of the root causes of problems, and even more importantly, the formulation and implementation of corrective actions. Failure mode and effect analysis identifies potential failures and their effects, calculating their risk and prioritising potential failure modes based on risk.120 In addition to examining patient risk, another strategy has focused on understanding the safety culture of a unit or organisation, with subsequent activities aimed at improving components of this culture.

Safety Culture

Measurement of the baseline safety culture facilitates an action plan for improvement. Safety culture has been defined as ‘the product of individual and group values, attitudes, perceptions, competencies, and patterns of behaviour that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organisation’s health and safety management.’121 It is commonly referred to as ‘the way we do things around here.’122 A widely used instrument to measure safety culture, the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ), focuses on six domains: teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, perceptions of management, working conditions and stress recognition.123 Interestingly, two studies in the USA that used the SAQ showed that nurses and doctors differed in their perceptions of safety culture.124,125

One strategy to improve the safety culture has involved identifying factors that make organisations safe, which in turn allows initiatives to be developed that target areas of specific need. For example, five characteristics of organisations that have been able to achieve high reliability include:126

1. safety viewed as a priority by leaders

2. flattened hierarchy that promotes speaking up about concerns

Many of these five factors fall under the category of ‘non-technical’ skills.127 Other non-technical skills include situational awareness and decision making. Importantly these skills can be learned. For example, the Anaesthetists’ Non-Technical Skills (ANTS) is a training program developed in Scotland, that focuses on task management, team working, situational awareness and decision making.127 A second training program, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS), developed in the US, is designed to develop competency in four areas: team leadership, situational monitoring, mutual support (or back-up behaviours) and communication.128 Thus, training programs can be used to help develop various non-technical skills, ultimately promoting a culture of safety within the critical care environment.

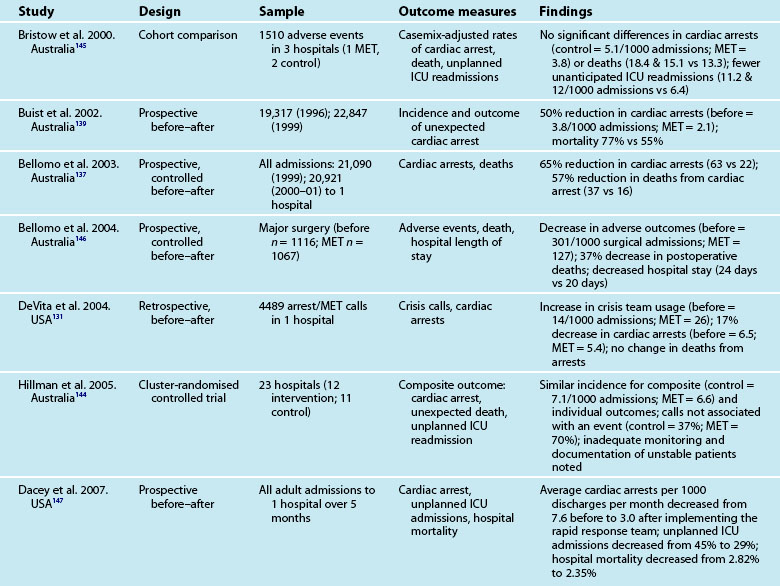

Rapid Response Systems

Rapid Response Systems (RRS) are systems that have developed to first recognise, and then to provide emergency response to, patients who experience acute deterioration.129,130 The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care have identified eight essential elements in a RRS (Table 3.8).129

| Domain | Element | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical processes | Measurement and documentation | Vital signs, oxygen saturation and level of consciousness should be undertaken regularly on all acute care patients |

| Escalation of care | A protocol for the organisation’s response in dealing with abnormal physiological measures and observations including appropriate modifications to nursing care, increased monitoring, medical review and calling for assistance. | |

| Rapid response systems | When severe deterioration occurs, medical emergency teams, outreach teams or liaison nurses are available to respond. | |

| Clinical communication | Structured communication protocols are used to hand over information about the patient. | |

| Organisational prerequisites | Organisational supports | Executive and clinical leadership support and a formal policy framework for recognition and response systems should exist. |

| Education | Education should cover clinical observation, identification of deterioration, escalation protocols, communication strategies, and skills in initiating early interventions. | |

| Evaluation, audit and feedback | Ongoing monitoring and evaluation are required to track changes in outcomes over time and to check that the RRS is operating as planned. | |

| Technological systems and solutions | As relevant technologies are developed, they should be incorporated into service delivery, after considering evidence of their efficacy and cost as well as potential unintended consequences. |

Recently, the recognition aspect of RRS has been referred to as the afferent limb, whereas the response aspect has been called the efferent limb.131 The afferent limb involves the use of various track and trigger systems to identify patients at risk of deterioration. The efferent limb is comprised of teams of specialists who provide treatment and care to the deteriorating patient. Each of these components is briefly described.

Afferent Limb

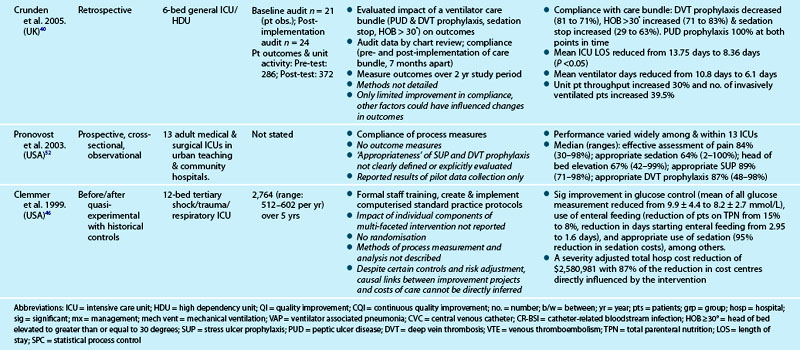

Recognising the deteriorating patient, the afferent limb has focused on measuring clinical signs including vital signs, level of consciousness and oxygenation as well as acting on abnormalities in these measurements.129,130 A variety of scoring systems to identify ward patients with clinical deterioration have evolved as part of the development of critical care outreach,132 including the MET,133 early warning scoring (EWS),134 and patient-at-risk (PAR) criteria135,136 (see Table 3.9).

Other modified criteria are also in use.131,137–139 All systems identify abnormalities in commonly measured parameters (e.g. respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, neurological status). Other parameters used in patient assessment are oxygen saturation, temperature in PAR, urine output in PAR and EWS. The EWS/PAR systems include an ordinal scoring approach used as calling criteria for contacting the admitting medical team, ICU staff, the critical care outreach team or the MET, depending on the severity of the patient’s clinical deterioration and the resources available in the local clinical environment.

Efferent Limb

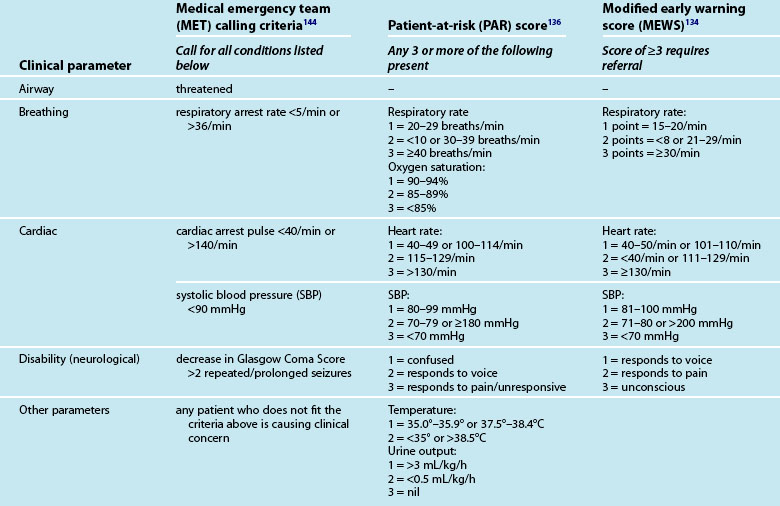

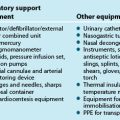

The efferent limb involves the response to clinical deterioration. Two types of services have emerged to respond to deteriorating ward patients: Rapid Response Team (RRT) and ICU Liaison Nurses (LN). RRT is an umbrella term that refers to the teams responding to deteriorating patients.131 In Australia and New Zealand these teams are known as Medical Emergency Teams (MET), while in the United Kingdom they are referred to as Critical Care Outreach Teams (CCOT) and in North America the umbrella term of RRT is used. Irrespective of the title used, RRT generally comprise an experienced nurse and a doctor, and in the case of North America, may include a respiratory therapist. RRT have replaced the traditional ‘cardiac arrest’ team in many hospitals, although the evidence base on the effectiveness of the system is not clear. RRT assess deteriorating patients and then initiate emergency treatments to stabilise patients. Table 3.10 summarises some of the recent research on RRT. To note, most of the research has been undertaken in Australia, where MET were first developed.

The second type of efferent limb service is the ICU LN. LN services are a proactive strategy aimed at ward patients who have complex care needs that may overextend the skills of ward staff.140–142 In some hospitals LNs are part of the RRT. The role of the ICU LN is described as one of education of both staff and patients, supervision, follow-up of patients discharged from ICU, liaison and coordination with ward staff, assessment, assistance in development and coordination of the discharge plan, preparation of written documentation and referral.143 Despite the broadly defined nature of this role, one of its primary aspects involves supporting other staff, both within and beyond the ICU, in providing continuity of care for ICU patients.143 The scope of practice, qualifications and job titles of LNs have yet to be standardised, although a LN Special Interest Group now exists under the auspices of the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses. This group is working to develop a standard role description and core competencies for the LN role. Interestingly, while the literature about LNs is predominantly from Australia and New Zealand, the service is now emerging in countries such as Canada and Scotland.

Summary

Research vignette

Learning activities

• Using each domain of quality and safety as headings (i.e. structure, process, culture, outcome), list some of the key considerations for a quality improvement project targeting pressure ulcer prevention in your unit.

• Examine the patterns of incidence for a high-frequency adverse event (e.g. medication error) in your unit over the past 12 months. What were the causes of incidents? What targeted strategies could be used to reduce the incidence of these adverse events?

• Identify and provide a rationale for an aspect of care that might benefit from the use of a checklist in your unit. Develop some specific checklist items that you think should be included.

• Describe how technology is used in your unit to improve care delivered to patients. Using the information outlined in the section on information and communication technologies, identify where there is potential to use technology to improve care delivery further. Use examples specific to your unit.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ahrq.gov.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au.

Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS). http://www.achs.org.au/.

Intensive Care Coordination and Monitoring Unit (ICCMU). New South Wales Health http://intensivecare.hsnet.nsw.gov.au

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), USA. http://www.ihi.org/ihi.

The Joint Commission (USA). http://www.jointcommission.org/.

National E-Health Transition Authority. http://www.nehta.gov.au/.

National Health and Medical Research Council. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/.

National Quality Forum. http://www.qualityforum.org/.

World Health Organization Patient Safety. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/en.

1 Valentin A, Capuzzo M, Guidet B, Moreno R, Dolanski L, et al. Patient safety in intensive care: results from the multinational Sentinel Events Evaluation (SEE) study. Intens Care Med. 2006;32:1591–1598.

2 Lohr K, Schroeder S. A strategy for quality assurance in medicine. New Engl J Med. 1990;322:1161–1171.

3 Rogers AE, Dean GE, Hwang WT, Scott LD. Role of registered nurses in error prevention, discovery and correction. Qual Safe Health Care. 2008;17:117–121.

4 Cullum N, Cilicska D, Haynes RB, Marks S. Evidence-based nursing: an introduction. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

5 National Health and Medical Research Council. How to use the evidence: assessment and application of scientific evidence. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2000.

6 Jennings BM, Loan LA. Misconceptions aming nurses about evidence-based practice. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33(2):121–127.

7 Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–1230.

8 Ilott I, Rick J, Patterson M, Turgoose C, Lacey A. What is protocol-based care? A concept analysis. J Nurs Manag. 2006;14:544–552.

9 Miller M, Kearney N. Guidelines for clinical practice: development, dissemination and implementation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41:813–821.

10 Intensive Care Coordination and Monitoring Unit. New South Wales Department of Health http://intensivecare.hsnet.nsw.gov.au/state-wide-guidelines, 2010. [Cited March 2011]. Available from

11 Donabedian A. Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care. Milbank Q. 2005;44(3):691–729.

12 Pronovost PJ, Sexton JB, Pham JC, Goeschel CA, Winters BD. Measurement of quality and assurance of safety in the critically ill. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30:169–179.

13 Wilson RM, Van Der Weyden MB. The safety of Australian healthcare: 10 years after QAHS. Med J Aust [editorial]. 2005;182:260–261.

14 Speroff TP, O’Connor GT. Study designs for PDSA quality improvement research. Qual Manage Health Care. 2004;13(1):17–32.

15 Curtis JR, Cook DJ, Wall RJ, Angus DC, Bion J, et al. Intensive care unit quality improvement: a ‘how-to’ guide for the interdisciplinary team. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:211–218.

16 Ehsani JP, Jackson T, Duckett SJ. The incidence and cost of adverse events in Victorian hospitals 2003–04. Med J Aust. 2006;184(11):551–555.

17 Runciman WB, Roughead EE, Semple SJ, Adams RJ. Adverse drug events and medication errors in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:i49–i59.

18 Needham DM, Thompson DA, Holzmueller C, Dorman T, Lubomski LH, et al. A system factors analysis of airway events from the Intensive Care Unit Safety Reporting System (ICUSRS). Crit Care Med. 2004;32(11):2227–2231.

19 Beckmann U, Gillies DM, Berenholtz SM, Wu AW, Pronovost P. Incidents relating to the intra-hospital transfer of critically ill patients: an analysis of the reports submitted to the Australian Incident Monitoring Study in Intensive Care. Intens Care Med. 2004;30(8):1579–1585.

20 Capuzzo M, Nawfal I, Campi M, Valpondi V, Verri M, Alvisi R. Reporting of unintended events in an intensive care unit: comparison between staff and observer. BMC Emerg Med. 2005;5(1):1–7.

21 Wolff AM, Bourke J, Campbell IA, Leembruggen DW. Detecting and reducing hospital adverse events: outcomes of the Wimmera clinical risk management program. Med J Aust. 2001;174:621–625.

22 Beckmann U, West L, Groombridge GJ, Baldwin I, Hart GK, et al. The Australian Incident Monitoring study in Intensive Care: AIMS-ICU. The development and evaluation of an incident reporting system in intensive care. Anaesth Intens Care. 1996;24(3):314–319.

23 Baldwin I, Beckmann U, Shaw L, Morrison A. Australian incident monitoring study in intensive care: local unit review meetings and report management. Anaesth Intens Care. 1998;26:294–297.

24 Classen DC, Metzger J. Improving medication safety: the measurement conundrum and where to start. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:i41–i47.

25 Koppel R. What do we know about medication errors via a CPOE system versus those made via handwritten orders? Crit Care. 2005;9:R516–R517.

26 Beckmann U, Bohringer C, Carless R, Gillies DM, Runciman WB, Pronovost PJ. Evaluation of two methods for quality improvement in intensive care: facilitated incident monitoring and retrospective medical chart review. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1006–1011.

27 Taxis K, Barber N. Ethnographic study of incidence and severity of intravenous drug errors. BMJ. 2003;326:684–687.

28 Malashock CM, Shull SS, Gould DA. Effect of smart infusion pumps on medication errors related to infusion device programming. Hosp Pharm. 2004;39:460–469.

29 Rothschild J, Landrigan CP, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Lockley SW, et al. The Critical Care Safety Study: the incidence and nature of adverse events and serious medical errors in intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(8):1694–1700.

30 Apkon M, Leonard J, Probst L, DeLizio L, Vitale R. Design of a safer approach to intravenous drug infusions: failure mode effects analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;13:265–271.

31 Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI, Dunsmuir WT, Day RO. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):683–690.

32 Kliger J. Giving medication administration the respect it is due: comment on “association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors”. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):690–692. [Invited Commentary]

33 Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society, Australian Council on Healthcare Standards. Intensive care indicators. Sydney: ACHS; 2011.

34 Esmail R, Kirby A, Inkson T, Boiteau P. Quality improvement in the ICU: a Canadian perspective. J Crit Care. 2005;20:74–78.

35 Ilan R, Fowler R. Brief history of patient safety culture and science. J Crit Care. 2005;20:2–5.

36 Pronovost PJ, Rinke ML, Emery K, Dennison C, Blackledge C, Berenholtz S. Interventions to reduce mortality among patients treated in intensive care units. J Crit Care. 2004;19(3):158–164.

37 Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, Lipsett PA, Simmonds T, Haraden C. Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care. 2003;18(2):71–75.

38 Pronovost PJ, Holzmueller C. Partnering for quality. J Crit Care. 2004;19(3):121–129.

39 Vincent J-L. Give your patient a FAST HUG (at least) once a day. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(6):1225–1229.

40 Crunden E, Boyce C, Woodman H, Bray B. An evaluation of the impact of the ventilator care bundle. Nurs Crit Care. 2005;10(5):242–246.

41 Resar R, Pronovost P, Haraden C, Simmonds T, Rainey T, Nolan T. Using a bundle approach to improve ventilator care processes and reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Qual Pat Saf. 2005;31(5):243–248.

42 Papadimos T, Hensley S, Duggan J, Khuder S, Borst M, et al. Implementation of the “FASTHUG” concept decreases the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a surgical intensive care unit. Pat Saf Surg. 2008;2(1):3.

43 Hatler CW, Mast D, Corderella J, Mitchell G, Howard K, et al. Using evidence and process improvement strategies to enhance healthcare outcome for the critically ill: A pilot project. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15(6):549–555.

44 Wall RJ, Ely EW, Elasy TA, Dittus RS, Foss J, et al. Using real time process measurements to reduce catheter related bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:295–302.

45 Keroack MA, Cerese J, Cuny J, Bankowitz R, Neikirk HJ, Pingleton SK. The relationship between evidence-based practices and survival in patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation in academic medical centers. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21:91–100.

46 Clemmer TP, Spuhler VJ, Oniki TA, Horn SD. Results of a collaborative quality improvement program on outcomes and costs in a tertiary critical care unit. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(9):1768–1774.

47 Ilan R, Fowler RA, Geerts R, Pinto R, Sibbald WJ, Martin CM. Knowledge translation in critical care: Factors associated with prescription of commonly recommended best practices for critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(7):1696–1702.

48 Hales BM, Pronovost P. The checklist – a tool for error management and performance improvement. J Crit Care. 2006;21:231–235.

49 Dobkin E. Checkoffs play key role in SICU improvement: checklist helps team follow care plan [Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv [serial on the Internet]] http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0NUZ/is_10_10/ai_109026749/?tag=content;col1, 2003. Available from

50 Piotrowski MM, Hinshaw DB. The safety checklist program: creating a culture of safety in intensive care units. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(6):306–315.

51 Ursprung R, Gray JE, Edwards WH, Horbar JD, Nickerson J, et al. Real time patient safety audits: improving safety every day. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:284–289.

52 Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz S, Ngo K, McDowell M, Holzmueller C, et al. Developing and pilot testing quality indicators in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2003;18(3):145–155.

53 Hewson KM, Burrell AR. A pilot study to test the use of a checklist in a tertiary intensive care unit as a method of ensuring quality processes of care. Anaesth Intens Care. 2006;34:322–328.

54 DuBose JJ, Inaba K, Shiflett A, Trankiem C, Teixeira P, et al. Measureable outcomes of quality improvement in the trauma intensive care unit: The impact of a daily quality rounding checklist. J Trauma. 2008;64:22–29.

55 Byrnes MC, Schuerer DJE, Schallom ME, Sona CS, Mazuski JE, et al. Implementation of a mandatory checklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence-based intensive care unit practices. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):1–7.

56 Hart EM, Owen H. Errors and omissions in anesthesia: A pilot study using a pilot’s checklist. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:246–250.

57 Hewson-Conroy KM, Elliott D, Burrell AR. Quality and safety in intensive care – A means to an end is critical. Aust Crit Care. 2010;23(3):109–129.

58 Australian Health Ministers’ Conference. National E-Health strategy summary. Melbourne, Australia; December 2008.

59 National E-Health Transition Authority. NEHTA Strategic Plan 2009/10 to 2011/12. Sydney, Australia; November 2009.

60 Lee T-T. Nurses’ adoption of technology: application of Rogers’ innovation-diffusion model. Appl Nurs Res. 2004;17(4):231–238.

61 Ward NS. The accuracy of clinical information systems. J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):221–225.

62 Clemmer TP. Computers in the ICU: Where we started and where we are now. J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):201–207.

63 Seiver A. ICU bedside technology: past, present and future. Crit Care Clin. 2000;16:601–621.

64 Levy MM. Computers in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):199–200.

65 Clemmer TP. Monitoring outcomes with relational databases: does it improve quality of care? J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):243–247.

66 Rubenfeld GD. Using computerized medical databases to measure and to improve the quality of intensive care. J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):248–256.

67 Davidson P, Daly J, Romanini J, Elliott D. Quality use of medicines (QUM) in critical care: an imperative for best practice. Aust Crit Care. 2001;14:122–126.

68 Wilson K, Sullivan M. Preventing medication errors with smart infusion technology. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:177–183.

69 Rothschild JM, Keohane CA, Cook EF, Orav EJ, Burdick E, et al. A controlled trial of smart infusion pumps to improve medication safety in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:533–540.

70 Manjoney R. Clinical information systems market: an insider’s view. J Crit Care. 2004;19:215–220.

71 Marasovic C, Kenney C, Elliott D, Sindhusake D. A comparison of nursing activities associated with manual and automated documentation in an Australian intensive care unit. Comput Nurs. 1997;15(4):205–211.

72 Wong DH, Gallegos Y, Weinger MB, Clack S, Slagle J, Anderson CT. Changes in intensive care unit nurse task activity after installation of a third-generation intensive care unit information system. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(10):2488–2494.

73 Fraenkel DJ, Cowie M, Daley P. Quality benefits of an intensive care clinical information system. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(1):120–125.

74 Marasovic C, Kenney C, Elliott D, Sindhusake D. Attitudes of Australian nurses towards the implementation of a clinical information system. Comput Nurs. 1997;15:91–98.

75 Ward NS, Snyder JE, Ross S, Haze D, Levy MM. Comparison of a commercially available clinical information system with other methods of measuring critical care outcomes data. J Crit Care. 2004;19(1):10–15.

76 Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11(2):104–112.

77 Van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(2):138–147.

78 Frassica JJ. CIS: Where are we going and what should we demand from industry? J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):226–233.

79 Rothschild J. Computerized physician order entry in the critical care and general inpatient setting: a narrative review. J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):271–278.

80 Christian S, Gyves H, Manji M. Electronic prescribing. Care Crit Ill. 2004;20:68–71.

81 Ali NA, Mekhjian HS, Kuehn PL, Bentley TD, Kumar R, et al. Specificity of computerized physician order entry has a significant effect on the efficiency of workflow for critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(1):110–114.

82 Perez F, Winters JL, Gajic O. The addition of decision support into computerized physician order entry reduces red blood cell transfusion resource utilization in the intensive care unit. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(7):631–633.

83 Thursky KA, Buising K, Bak N, Macgregor L, Street AC, et al. Reduction of broad-spectrum antibiotic use with computerized decision support in an intensive care unit. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(3):224–231.

84 Sintchenko V, Iredell JR, Gilbert GL, Coiera E. Handheld computer-based decision support reduces patient length of stay and antibiotic prescribing in critical care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(4):398–402.

85 Eslami S, De Keizer NF, Abu-Hanna A, De Jonge E, Schultz MJ. Effect of a clinical decision support system on adherence to a lower tidal volume mechanical ventilation strategy. J Crit Care. 2009;24:523–529.

86 Lyerla F, LeRouge C, Cooke DA, Turpin D, Wilson L. A nursing clinical decision support system and potential predictors of head-of-bed position for patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(1):39–47.

87 Sim I, Gorman P, Greenes RA, Haynes RB, Kaplan B, et al. Clinical decision support systems for the practice of evidence-based medicine. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2001;8(6):527–534.

88 Sucher JF. Computerized clinical decision support: a technology to implement and validate evidence based guidelines. J Trauma. 2008;64(2):520–537. [Review article]

89 Overhage M, Tierney WM, Zhou X, McDonald CJ. A randomized trial of ‘corollary orders’ to prevent errors of omission. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4:364–375.

90 Kucher N, Koo S, Quiroz R, Cooper JM, Paterno MD, et al. Electronic alerts to prevent venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients. New Engl. J Med. 2005;352(10):969–977.

91 van Wyk JT, van Wijk AM, Sturkenboom MCJM, Mosseveld M, Moorman PW, van der Lei J. Electronic alerts versus on-demand decision support to improve dyslipidemia treatment. A cluster randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2008;117:371–378.

92 Coleman RW. Translation and interpretation: the hidden processes and problems revealed by computerized physician order entry systems. J Crit Care. 2004;19(4):279–282.

93 Tooey MJ, Mayo A. Handheld technologies in a clinical setting: state of the technology and resources. AACN Clin Issues. 2003;14:342–349.

94 Craig AE. PDAs and smartphones: clinical tools for nurses [Medscape Business of Medicine [serial on the Internet]] www.medscape.com, 2009. Available from

95 Lapinsky S, Wax R, Showater R, Martinez-Motta JC, Hallett DC, et al. Prospective evaluation of an internet-linked handheld computer critical care knowledge access system. Crit Care. 2004;8:R414–R421.

96 George LE, Davidson LJ, Serapiglia CP, Barla S, Thotakura A. Technology in nursing education: A study of PDA use by students. J Prof Nurs. 2010;26(6):371–376.

97 Kuiper RA. Metacognitive factors that impact student nurse use of point of care technology in clinical settings. Int J Nurs Educ Schol. 2010;7(1):1–15.

98 Martinez-Motta JC, Walker RG, Stewart TE, Granton J, Abrahamson S, Lapinsky SE. Critical care procedure logging using handheld computers. Crit Care. 2004;8(5):R336–R342.

99 Bochicchio GV, Smit PA, Moore R, Bochicchio K, Auwaerter P, et al. Pilot study of a web-based antibiotic decision management guide. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(3):459–467.

100 Iregui M, Ward S, Clinikscale D, Clayton D, Kollef MH. Use of a handheld computer by respiratory care practitioners to improve the efficiency of weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(9):2038–2043.

101 Rosenfeld B, Dorman T, Breslow M, Pronovost PJ, Jenckes MW, et al. Intensive care unit telemedicine: alternate paradigm for providing continuous intensivist care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3925–3931.

102 Afessa B. Tele-intensive care unit: the horse out of the barn. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(1):292–293. [Editorial]

103 Breslow M, Rosenfeld B, Doerfler M, Burke G, Yates G, et al. Effect of a multiple-site intensive care unit telemedicine program on clinical and economic outcomes: An alternative paradigm for intensivist staffing. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(1):31–38.

104 Vespa PM, Miller C, Hu X, Nenov V, Buxey F, Martin NA. Intensive care unit robotic telepresence facilitates rapid physician response to unstable patients and decreased cost in neurointensive care. Surg Neurol. 2006;67(2007):331–337.

105 Westbrook J, Coiera EW, Brear M, Stapleton S, Rob M, et al. Impact of an ultrabroadband emergency department telemedicine system on the care of acutely ill patients and clinicians’ work. Med J Aust. 2008;188(12):704–708. [Research]

106 Thomas EJ, Lucke JF, Wueste L, Weavind L, Patel B. Association of telemedicine for remote monitoring of intesive care patients with mortality, complications, and length of stay. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302(24):2671–2678.

107 Morrison JL, Cai Q, Davis N, Yan Y, Berbaum ML, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of the electronic intensive care unit: results from two community hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(1):2–8.

108 Yoo JS, Dudley RA. Evaluating telemedicine in the ICU. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;302(24):2705–2706.

109 Curran VR. Tele-education. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(2):57–63.

110 Simpson RL. See the future of distance education. Nurs Manage. 2006;37(2):42. 44, 46–51

111 Beeckman D, Schoonhoven L, Boucque H, Van Maele G, Defloor T. Pressure ulcers: e-learning to improve classification by nurses and nursing students. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(13):1697–1707.

112 Maag M. The potential use of “blogs” in nursing education. Comput Inform Nurs. 2005;23(1):16–24.

113 Kreideweis J. Indicators of success in distance education. Comput Inform Nurs. 2005;23(2):68–72.

114 Moreno RP, Rhodes A, Donchin Y. Patient safety in intensive care medicine: The Declaration of Vienna. Intens Care Med. 2009;35:1667–1672.

115 Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

116 Institute of Medicine. Patient safety: Achieving a new standard of care. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2003.

117 European Agency Safety Improvement for. Patients in Europe (SIMPATIE). Cited 1 February http://www.simpatie.org, 2010. Available from

118 Bagian JP, Gosbee J, Lee CZ, Williams L, McKnight SD, Mannos DM. The Veterans Affairs root cause analysis system in action. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28:531–545.

119 Middleton S, Walker C, Chester R. Implementing root cause analysis in an area health service: views of the participants. Aust Health Rev. 2005;29:422–428.

120 McDonough JE. Proactive hazard analysis and health care policy. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund; 2002.

121 Sorro JS, Nieva VF. Hospital survey on patient safety culture. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004.

122 Davies HT, Nutley SM, Mannion R. Organisational culture and quality of health care. Qual Health Care. 2000;9:111–119.

123 Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB, Rowan K, Vella K, et al. The Safety Attitudes Questionniare: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(44):1472–1482.

124 Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):956–959.

125 Huang DT, Clermont G, Sexton JB, Karlo CA, Miller RG, et al. Perceptions of safety culture vary across the intensive care units of a single institution. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):165–176.

126 Clarke JR, Lerner JC, Marella W. The role for leaders of health care organizations in patient safety. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(5):311–318.

127 Reader T, Flinn R, Lauche K, Cuthbertson BH. Non-technical skills in the intensive care unit. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(5):551–559.

128 Clancy CM, Tornberg DN. TeamSTEPPS: Assuring optimal teamwork in clinical settings. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22:214–217.

129 Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Consensus Statement: Essential Elements for Recognising and Responding to Clinical Deterioration. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2010.

130 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Acutely Ill Patients in Hospital: Recognition of and Response to Acute Illness in Adults in Hospital. London: Author; 2007.

131 DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, et al. Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Safe Health Care. 2004;13:251–254.

132 McArthur-Rouse F. Critical care outreach services and early warning scoring systems: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36:696–704.

133 Lee A, Bishop G, Hillman KM, Daffurn K. The medical emergency team. Anaesth Intens Care. 1995;23:183–186.

134 Morgan RJM, Williams F, Wright MM. An early warning scoring system for detecting developing critical illness. Clin Intens Care. 1997;8:100.

135 Goldhill DR, Worthington L, Mulcahy A, Tarling M, Sumner A. The patient at risk team: identifying and managing seriously ill ward patients. Anesth. 1999;55:853–860.

136 Goldhill DR, McNarry AF, Mandersloot G, McGinley A. A physiologically-based early warning score for ward patients: the association between score and outcomes. Anesth. 2005;60:547–553.

137 Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, Buckmaster J, Hart GK, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003;179:283–287.

138 Hodgetts TJ, Kenward G, Vlackonikolas I, Payne S, Castle N. The indentification of risk factors for cardiac arrest and formulation of activation criteria to alert a medical emergency team. Resusc. 2002;54:125–131.

139 Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in a hospital: a preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324:387–390.

140 UK NHS Modernisation Agency. The National Outreach Report. London: UK Department of Health; 2003.

141 Chaboyer W, James H, Kendall M. Transitional care after the intensive care unit: current trends and future directions. Crit Care Nurs. 2005;25:1–10.

142 Chaboyer W, Foster MM, Foster M, Kendall E. The intensive care unit liaison nurse: towards a clear role description. Intens Crit Care Nurs. 2004;20:77–86.

143 Russell S. Reducing readmissions to the intensive care unit: employment of a follow-up nurse. Heart & Lung. 1999;28:365–372.

144 Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, Bellomo R, Brown D, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2091–2097.

145 Bristow PJ, Hillman KM, Chey T, Daffum K, Jacques T. Rates of in-hospital arrests, deaths and critical care admissions: the effect of the medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2000;173:236–250.

146 Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:916–921.

147 Dacey MJ, Mirza ER, Wilcox V, Doherty M, Mello J, et al. The effect of a rapid response team on major clinical outcome measures in a community hospital. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9):2076–2082.