Chapter 8 Quality and Outcome Measures for Medical Rehabilitation

Quality health care can be defined as providing the best possible outcomes, safety, and service. Quality patient care should be the first priority of every rehabilitation professional. Turning this priority into practice can be difficult for many reasons. For example, sometimes scientific clarity on what constitutes quality is lacking. Financial incentives such as fee-for-service arrangements that reward activity rather than outcomes can also hamper quality efforts and lead to overuse of a broad variety of health care services.22 Where health services are concerned, more is not necessarily better. To help determine what constitutes quality and how health professionals should measure it, this chapter discusses quality improvement, evidence-based outcome measures, practice improvement, safety, and accreditation.

Efforts to measure and reward quality care have grown exponentially over the last decade. In 2007, more than 100 million Americans were enrolled in health plans that measure and report quality of care. In 2008, 240 preferred provider organizations, covering more than 42 million members, joined their health maintenance organization counterparts and reported audited Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) data to the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). The total number of Americans included in quality reporting increased 29% in 2008 and has more than doubled since 2000.22

Quality Improvement

A general principle behind CQI is that 85% of errors occur because of a suboptimal system, and only 15% of errors are attributable to individuals.1 CQI attempts to determine “what is wrong with this system and why did an error occur.” (The system failed the employee rather than the reverse.) The evidence suggesting that quality problems are largely caused by systes failures has led to an emerging focus on the organizational factors necessary to improve the quality of health care. Adapting these principles to medicine presents unique challenges. Physicians often resist standardizing care, fearing a loss of autonomy or loss of their ability to provide individualized care. A work environment with needless variation increases the likelihood of medical errors by the health care personnel involved. There is frequently an inherent tension between standardization to excellence and physician autonomy that needs to be understood and confronted.

For two decades, health care workers have had varying degrees of success using the principles of CQI to improve the quality of patient care.8 Experts using CQI in health care believe it is possible to improve quality and save money at the same time. The objectives of quality improvement are to ensure access to new technology, good procedural outcomes, and patient satisfaction while simultaneously identifying opportunities for expense reduction. Integrated quality-improvement initiatives help ensure that the research of today becomes the practice of tomorrow.

Quality Outcomes/Practice Measures

Clinicians have greater credibility with payers and policymakers if they collect and share outcomes that demonstrate the economic benefits of an intervention as well as the impact on health, function, and quality of life.26 For patients and their families struggling to come to terms with a newly acquired disability, it can be hard to think of the “cost” part. The key for them is generally to achieve the best possible outcome “whatever the cost.” As clinicians respond to the public demand for person-centered care, we must recognize the current financial pressure on health care systems and the need to share a scarce resource equitably among a large group of patients.

The traditional medical model focuses on diagnosis and treatment of acute disease. For many medical decisions, it is not always clear that treatment is the best option. For instance, there is growing evidence that the amount of surgery that can be justified on the basis of traditional practice guidelines actually exceeds the amount of surgery that patients want when fully informed.34 Shared decision making allows patients and care providers to determine whether the patient should undergo diagnostic testing or receive therapy. In contrast to acute diseases, chronic conditions are usually not cured. As a result, patients must adapt to these problems. Because diagnosis and treatment might detect and address an aspect of a disease without extending life expectancy or improving quality of life, patients and physicians need to have candid discussions to equip patients to make informed decisions about what combination of treatment and adaptation best fits their needs. To use a surgical analogy, although clinicians can detect and attempt to “fix” prostate cancer, the real challenge is deciding whether diagnosis and treatment are valuable. Crahn et al.13 discovered that screening 70-year-old men for prostate cancer reduced quality-adjusted life days. The reason for this negative impact is that screening identifies prostate cancer in many men who would have died of other causes. These men, once identified, are likely to engage in a series of treatments that can significantly reduce their quality of life. The treatment causes harm without producing substantial benefits. Clinicians in physical medicine and rehabilitation also need to be alert to the balance of burden and benefit of treatment in helping patients reach personal choices about their care. Creating an outcome measure at the individual patient level (e.g., to walk two blocks, to manage grooming independently, to cycle without hip pain) is a way of incorporating principles from the overall quality movement to benefit individual patients.

Pay for Performance

There are currently more than 100 P4P projects nationally.11 Employers, private payers, Congress, and CMS are all moving forward with P4P programs or variations of it. The measures used to assess quality and cost-effectiveness in P4P programs vary greatly. Many of the measurements used in P4P initiatives look at process data. If someone should have received a type of care, did that patient in fact receive it? The “percentage compliance” measures are well suited to outcomes measures.

The HEDIS is a tool used by more than 90% of Americans with managed health care plans and a growing number of preferred provider organization plans to measure performance on important dimensions of care and service. By providing objective clinical performance data, HEDIS provides purchasers and consumers the means to make informed comparison among health plans on the basis of performance. HEDIS includes performance measures related to dozens of important health care issues including comprehensive diabetes care (yearly foot examinations); the use of imaging studies and recommendations for exercise in patients with low back pain; the use of high-risk medications in the elderly; and other strategic safety initiatives. National Quality Forum–endorsed measures can be found at http://www.ncqa.org.

Since 1996, the NCQA has reported to the nation on the state of health care quality. One in three Americans is enrolled in a health plan that is transparent regarding the measurement of the quality of its care and services. For the ninth consecutive year, health care delivered by plans that measure and report performance data continues to improve despite rising costs and a slowing national economy.23

Patient Safety

The Institute of Medicine report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, highlighted the opportunity to reduce preventable medical errors. Since its release, patient safety has become a preeminent issue for health care.16 Wrong-site, wrong-procedure, or wrong-person surgery suggests problems with the accuracy and completeness of the information brought to the point of care, the quality of communication, and the degree of teamwork among the members of the team. To Err Is Human found that the knowledge about error reduction was easily accessible, but the implementation of the knowledge was lacking. After this report, patients and payers began demanding a higher standard of care. The public, hospital leaders, and health care professionals want to reduce the risk of similar system failures occurring in the future.

The 2001 Committee on the Quality of Healthcare report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, states that there is a need to approach health care in a different way, one that focuses more directly on providing care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, efficient, and equitable.10 The report identifies these as specific aims for quality measurement and reporting. The Institute of Medicine’s seminal 2002 report, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality, outlines that health professionals must “cooperate, communicate, and integrate care in teams to ensure that care is continuous and reliable.”16 Formal quality improvement and outcomes monitoring systems aim to improve the effectiveness of care, reduce errors, and improve function and quality of life. These systems enable patients, families, referral sources, and payers to make better choices regarding level and type of rehabilitation needed.

Measures Development

Many quality measures were developed early in the quality improvement movement. For these early initiatives, the risks and rewards from measures were nominal. The goal was for local improvement. The results were not publicly reported. Many different private and public sector groups have attempted to design models to measure performance and report data. While progress has been made, the proliferation of multiple, uncoordinated, and sometimes conflicting initiatives has consequences for stakeholders. Without a uniform approach to select performance measures, conflicting initiatives divert limited resources away from quality measures and reporting. Although public statements of lives saved or errors prevented abound, consumers lack the tools to evaluate the validity of such statements. Hospital Compare was created through the efforts of the CMS, the Department of Health and Human Services, and other members of the Hospital Quality Alliance: Improving Care Through Information. Hospital Compare is a quality tool provided by Medicare to help patients compare the quality of care hospitals provide. The CMS Hospital Compare website can be found at http://www.hhs.gov.

Evidence-based practice requires that clinicians use objective outcomes measures to compare alternative approaches. Evidence-based practice has become the mantra of our modern health care system. Evidence-based practice implies that care is up-to-date, based on the best evidence, and “proven effective.” It is seen as adhering to a rigorous standard and likely to be associated with better overall care.25 Evidence-based guidelines need to be developed to establish standards for quality rehabilitative care.

Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement

PCPI measures are designed for physicians managing the care of patients with a particular condition. Measures focus on the patient and the care or procedures they receive. The Consortium develops patient-centered performance measures that are evidence based, statistically valid, and reliable (Box 8-1).

Rehabilitation Quality Outcome Measures

Physical medicine and rehabilitation professionals attempt to maximize patients’ function after a traumatic injury or other medical condition. Traditional outcome measures focus on functional ability. Classification systems like the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps37 and Nagi’s scheme of disablement22 have become standard ways to describe and conceptualize an individual’s disability.

Measures of functional ability like the FIM instrument27 have become core outcome instruments in rehabilitation medicine. FIM can be used as a clinical assessment tool as well as a risk adjuster in payment systems. Medical rehabilitation has developed systems for monitoring patient gains and basic functional activities, but more work is needed to translate these systems into performance measures that can be used to evaluate the work of specific rehabilitation physicians or hospitals. Because the FIM system focuses on the patient’s actual outcome, rather than just measuring a process step taken by the physician, it could serve as the basis for improved performance measurement.

The FIM instrument is composed of 18 items (13 motor, 5 cognitive) (Box 8-2) and uses a seven-level ordinal scale to measure major gradations of function. The FIM instrument documents a patient’s need for assistance from another person, a device, or both, taking into account the amount of time needed to complete the task.29 Functional status at admission and discharge is assessed by the FIM.27 Demographic, medical, and other variables were added to form the Uniform Data Set for Medical Rehabilitation.31 The FIM instrument is used by inpatient rehabilitation hospitals and some other facilities to track patients’ progress from admission through discharge and follow-up.28 To maintain data reliability, facilities must administer an FIM instrument credentialing test created by Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation (UDSMR) to clinicians every 2 years.31

Data Management

Each of the commercially available electronic data management systems has a detailed reporting capability. Facilities use reports for a variety of functions. To evaluate efficiency and effectiveness of a rehabilitation program, a facility closely examines total FIM ratings, change from admission to discharge, length of stay, length of stay efficiency (change in FIM ratings per day), discharge FIM ratings total, onset days, and discharge destination. During a patient’s rehabilitation stay, data are used to enhance communication among interdisciplinary team members, patients, and families. Aggregated data can be used as a communication tool to stakeholders (referral sources and payers), and for internal and external marketing. Outcomes data can be used for accreditation processes of The Joint Commission and Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF).20

e-Rehab Data

eRehabData includes tools to meet all the requirements of the Medicare Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities Prospective Payment System (IRF-PPS), The Joint Commission, and CARF. eRehabData accepts Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility–Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) assessments for both Medicare and non-Medicare patients and provides additional capacities for preadmission and follow-up assessments.

The WeeFIM II System

In 1987, a multidisciplinary team of pediatric clinicians began the work to adapt the FIM instrument to create a pediatric-specific outcomes measurement tool with a developmental framework. The WeeFIM II instrument measures the functional abilities associated with levels of disability in children aged 6 months to 7 years and older. The tool can be used for children older than 7 years if delays in functional development are experienced, and can be used across both the inpatient and outpatient settings.32

In 1994, a pediatric subscriber service was launched, allowing pediatric rehabilitation facilities to benchmark with other subscribing facilities across the nation. Clinicians noted that the WeeFIM II instrument was not specific enough for children younger than 3 years. As a result, the 0-3 Module was developed to be used in addition to the WeeFIM II instrument. The 0-3 Module measures precursors to function in 36 items across 3 domains: motor (16 items), cognitive (14 items), and behavior (6 items). The 0-3 Module is filled out by the child’s family members and takes about 15 minutes to complete.32

The LIFEware System

The LIFEware System is an Internet-based system created for tracking outcomes for a diverse range of outpatient populations, including those with the following impairments: musculoskeletal conditions, neurologic conditions, memory conditions, cardiopulmonary conditions, pain conditions, and joint-specific conditions. It contains assessment instruments and measures for evaluating patients across seven core functional domains: physical function, cognitive function, mood or affect, pain, social interaction, role participation, and satisfaction with treatment. The current database has more than 600,000 assessments. It supports medical necessity documentation compliance, helps substantiate ongoing patient treatment with payers, includes measures to support compliance with the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative, and provides a reliable and economic outcomes management system for outpatient programs.30

Patient-Reported Outcomes

The National Institutes of Health Roadmap initiative known as the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; http://www.nihpromis.org) uses item banks and computerized adaptive testing (CAT) for clinical research and clinical practice.21 CAT begins with clear definitions of important outcomes and references these definitions to specific questions gathered into large and well-studied pools or “banks” of items. Items can be selected from the banks to form customized short scales or administered in a sequence and length determined by a computer programmed for precision and clinical relevance.

Unlike a traditional test that asks the same questions to all test takers, a CAT instrument tailors the questions to the specific patient.14,19 If the patient’s response indicates that a task can be completed with no help, the CAT selects a question that asks about a task that is more difficult than the first task. If the response to the second question indicates that the patient cannot complete the more difficult task, the CAT selects a question that asks about a task that is easier than the task in the second question. This process continues until the computer identifies that the preprogrammed confidence interval has been met or the patient has answered the maximum number of items used to estimate the score.19

One example of a CAT functional outcomes system is the Activity Measure for Post Acute Care (AM-PAC). The AM-PAC instrument measures functional activities that are likely to be encountered by most adults during daily routines.2 Question banks are organized into three functional areas: basic mobility, daily activity, and applied cognitive. Because a common scale is used, functional scores can be tracked across the patient’s entire episode of care. The tool is currently in use in inpatient rehabilitation facilities, nursing homes, and outpatient rehabilitation settings. It can be used for internal quality improvement and benchmarking.3

Prospective Payment System

In an attempt to control the rapid growth of rehabilitation facilities and conserve Medicare dollars,29 Congress mandated the implementation of a prospective payment system (PPS) for inpatient rehabilitation facilities in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.4 Before the implementation of this payment system on January 1, 2002, the IRF-PAI was created to capture demographic, diagnostic, and functional information to be used for reimbursement29 (Box 8-3).

BOX 8-3 Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility–Patient Assessment Instrument

| Demographic information | Name, date of birth, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, payer |

| Medical information | Rehabilitation impairment group, event onset date, ICD-9 coding for etiologic diagnosis, complications during rehabilitation stay, and comorbid conditions |

| Hospitalization information | Admission date, discharge date, date(s) of program interruptions, discharge destination |

| FIM instrument | See Box 8-2 |

ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision.

Functional information is captured with a modified version of the FIM instrument15 (Box 8-4). At admission and discharge for Medicare Part A fee-for-service patients, inpatient rehabilitation facilities are required to complete the appropriate sections of the IRF-PAI, encode the data electronically into the IRF-PAI software product, and transmit the data electronically to the CMS.7

BOX 8-4 Summary of FIM Instrument Changes for Prospective Payment System

Reimbursement is determined by assigning patients into groups with similar resource usage and length of stay, called case-mixed groups (CMGs).29 A facility receives the same payment for the patient’s inpatient rehabilitation stay regardless of its duration, thus providing an incentive for rehabilitation hospitals in the United States to further reduce length of stay. Classification of a patient into a specific CMG is based on several factors, the first of which is the medical reason for admission to the inpatient rehabilitation facility. On admission, 1 of 85 impairment group codes that fall into 17 impairment groups is assigned.29 As an example, a patient admitted to inpatient rehabilitation for a stroke with right body involvement has an impairment group code of 1.2 under the stroke impairment group.5,29 The etiology of the impairment is represented on the IRF-PAI as an ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) code.29,33 Each impairment group falls into 1 of 21 distinct rehabilitation impairment categories (Table 8-1).29 The patient’s total admission motor FIM rating is also used to determine the CMG.29 For some CMGs the total admission cognitive FIM rating (total of five cognitive items) and the patient’s age at the time of admission affect CMG assignment.29

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 01 | Stroke |

| 02 | Traumatic brain injury |

| 03 | Nontraumatic brain injury |

| 04 | Traumatic spinal cord injury |

| 05 | Nontraumatic spinal cord injury |

| 06 | Neurologic |

| 07 | Fracture of lower extremity |

| 08 | Replacement of lower extremity joint |

| 09 | Other orthopedic |

| 10 | Amputation of lower extremity |

| 11 | Amputation, other |

| 12 | Osteoarthritis |

| 13 | Rheumatoid, other |

| 14 | Cardiac |

| 15 | Pulmonary |

| 16 | Pain syndrome |

| 17 | Major trauma without spinal cord injury/brain injury |

| 18 | Major trauma with spinal cord injury/brain injury |

| 19 | Guillain-Barré |

| 20 | Miscellaneous |

| 21 | Burns |

CMG assignment alone is not enough to accurately determine reimbursement for all patients. In addition to the primary impairment, the presence of a comorbid condition or conditions can have a major impact on the cost of inpatient rehabilitation care.29 It is the responsibility of the physician to clearly document any comorbid conditions so these are accurately captured on the IRF-PAI.29 Comorbidities that affect payment are separated into a high, medium, or low tier based on the costs associated with the comorbidities.29 Ninety-five CMGs have four relative weights: one for no comorbidities and three for the comorbidity tiers. These 95 CMGs are used for “typical” patients—patients with a length of stay longer than 3 days who complete the rehabilitation program and are discharged to a community setting.29 Five special CMGs that are unaffected by comorbidities exist for patients who have a length of stay of 3 days or less and patients who die while on an inpatient rehabilitation unit.7

Since implementation of the IRF-PPS and the use of the IRF-PAI in 2002, some unexpected data have emerged. Both admission and discharge FIM ratings decreased. This might be a reflection of changes in coding (modifications to the FIM instrument), changes in the types of patients admitted to inpatient rehabilitation facilities, and/or changes in the patient outcomes as represented by discharge FIM ratings and change in FIM ratings from admission to discharge.15 The number of patients transferred back to acute care increased from 4.8% in 1998 to 8.9% in 2003; this is likely explained by the change in the definition of program interruption from 30 days (before PPS) to 3 days (after PPS).15

Accreditation and Medicare Deemed Status

An inpatient rehabilitation hospital or unit must be recognized by CMS as meeting the Conditions of Participation to be paid for Medicare patients. Such recognition can be conferred by state health survey agencies. Alternatively, three accrediting agencies have been given authority by CMS to grant “deemed status” based on successful accreditation surveys: The Joint Commission, the American Osteopathic Association, and Det Norske Veritas, Inc. (http://www.jointcommission.org; http://www.osteopathic.org; http://www.dnv.com).

In addition to their standard setting and accreditation roles, accrediting bodies facilitate consensus and educate providers and other stakeholders on topics related to quality service. The CARF is recognized by both The Joint Commission and the NCQA as a specialty accreditation source for networks or health plans that provide rehabilitation services. Managed care organizations and other purchasers of rehabilitation services, while keenly focused on price at present, will eventually turn to purchasing services on the basis of value (quality and price).36

The Joint Commission

The Joint Commission is the nation’s oldest and largest standards-setting and accrediting body in health care. It is an independent, not-for-profit organization formed in 1951 to carry out the following20:

The Joint Commission standards help an organization (1) focus on quality and safety of care, treatment, and services; (2) identify areas needing improvement; (3) develop effective policies, processes, procedures, and guidelines; (4) increase coordination and collaboration among disciplines; and (5) provide consistent levels of care.20 Accreditation is recognized by federal agencies and insurers. Accreditation provides a benchmark within the health care industry that affirms delivery of high-quality patient care.

Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities

CARF has historically been oriented toward outcomes. CARF has worked to develop performance indicators for medical and other rehabilitation programs since its quality and accountability initiative in 1996. CARF is a private, not-for-profit organization that promotes quality rehabilitation services. CARF International is based in Tucson, Arizona, with offices in Washington, D.C., and Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. CARF currently accredits more than 5000 providers at more than 18,000 locations in the United States, Canada, Western Europe, and South America. Close to 6 million persons of all ages are served annually by CARF-accredited providers.6 The mission of CARF is to promote the quality, value, and optimal outcomes of services through accreditation that centers on enhancing the lives of the persons served. CARF believes in the following core values:

Accreditation by CARF is voluntary and fosters the growth and development of best practices in the rehabilitation field. Accreditation is available for a wide variety of programs including aging services, behavioral health, business and services management network, CARF-CCAC (Continuing Care Accreditation Commission) ASPIRE to Excellence, child and youth services, employment and community services, medical rehabilitation, One-Stop Career Center, opioid treatment programs, and vision rehabilitation services. CARF grants either a 1-year or 3-year accreditation. The 3-year accreditation is the highest level of accreditation that can be achieved. An organization receiving a 3-year accreditation outcome has put itself through a rigorous peer review process and has demonstrated to a team of surveyors during an on-site visit that its programs and services are of the highest quality, measurable, and accountable.6,9

The CARF standards have evolved and been refined over more than 40 years with the active support and involvement of providers, consumers, and purchasers of services. The standards define the expected input, processes, and outcomes of programs for persons served.6 Every year standards are reviewed and new ones developed to keep pace with changing conditions and current consumer needs. The updated standards are effective July 1 each year. Organizations are expected to demonstrate compliance with the standards for a minimum of 6 months before their site survey. CARF has many publications available to support organizations in achieving and maintaining accreditation of their programs and services.

CARF introduced a quality framework called ASPIRE to Excellence in 2008. ASPIRE represents a logical, action-oriented approach to continuous improvement that seamlessly integrates all organizational functions and the engaged input of stakeholders to ensure that organizational purpose, planning, and activity result in the desired outcomes. The ASPIRE name corresponds to six organizational actions6:

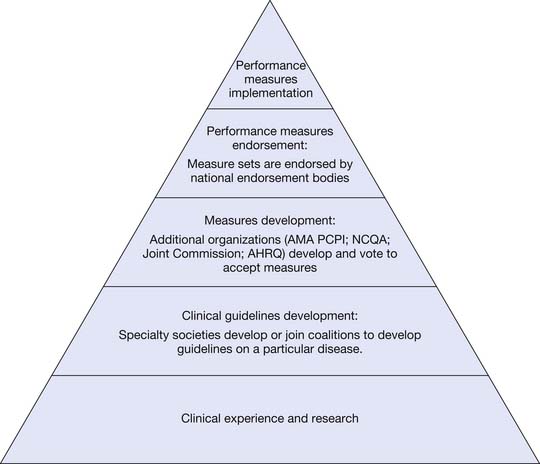

Systems of Measure Endorsement

Quality measures and reporting are powerful tools to drive quality improvement and close the health care quality gap. The Ambulatory Quality Alliance (AQA) and the National Quality Forum (NQF) both serve as national endorsement bodies for performance measure sets. Endorsement by these bodies gives assurance that a performance measure considers quality, efficiency, and cost of care (Figure 8-1).

Measures Implementation

A major user of measure sets is the CMS/Physician Quality Reporting Initiative program for Medicare reimbursement. Consumers and purchasers need reliable, comparative data to obtain value in health care and to generate market demand for quality. Providers also need comparative data to design improvement programs and compare their performance against regional and national benchmarks. NQF and AQA will likely be recognized as major driving forces for and facilitators of continuous quality improvement in American health care.

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education Quality Measures

Another motivating factor for this shift in CME delivery is the April 2007 report issued by the United States Senate Committee on Finance.24 The report alleged that CME is often a front for pharmaceutical and device companies to increase market share, and provided harsh criticism to the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the group that accredits medical education providers. The ACCME was accused of slow and lax oversight and enforcement of its standards, which measure accredited providers’ compliance. The report mainly focused on for-profit CME providers, not medical specialty societies. CME providers and the ACCME are attempting to prove CME has been and continues to be fair and balanced and free of commercial influence whether or not funding for CME was present. There is evidence that some CME providers, mainly in the for-profit area, have overstepped these boundaries, raising questions about whether CME with commercial support can be free of influence.

Real-time learning in a physician’s practice will save the cost of traveling to meetings. Practice-based learning is a promising continuing education approach in which clinicians review the care they deliver, compare the results with standards of excellence, and create a plan for improvement. Such learning is likely to play a growing role in the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) process of the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and other medical specialties. It is important to develop new approaches to both intraprofessional and interprofessional continuing education and determine how best to disseminate effective and efficient continuing educational materials.

Maintenance of Certification Enhancing Quality Outcomes

Since consumer expectations have changed, the ABMS is looking to make changes to itself and member boards. Although ABMS MOC is sometimes recognized by insurers, hospitals, credentialing organizations, and the federal government as a quality driver, MOC is under close scrutiny and its relevance is being questioned. With the recent launch of the 2008-2011 Enhanced Public Trust Initiative, the ABMS aims to answer the relevance question by bringing an increased commitment to quality health care and providing an opportunity to enhance the value of MOC to the public, diplomates, and member boards. The goal is for greater transparency and accountability with the public’s interest being the foremost concern. The initiative encourages a more cohesive ABMS Board Enterprise to ensure physician accountability, so that a board-certified diplomate of any specialty will be held to equal standards. Through the MOC program, board-certified physicians are expected to advance the standard of health care nationwide. The ABMS believes higher standards mean better care.33

Through MOC, physicians will make public their professional standing, cognitive expertise, and record of practice-based lifelong learning. At the same time, MOC will show diplomates how to improve specific aspects of practice. Physicians who wish to maintain their specialty certifications must meet MOC requirements on a periodic basis. For more information on MOC, visit the ABMS website (http://www.ABMS.org).

Conclusion

The effort to measure and report on health care quality has challenged what has been an article of faith for many: that health care in the United States is the best in the world. Despite increased spending, the fragmented nature of care and unwarranted variation suggest wasteful and inefficient health care resource allocation.13,35 The number of people whose access to care is blocked by factors such as lack of insurance and poor health literacy18 further highlights the gap between our nation’s people and excellent health care. The methodology of objective measurement that revealed the problems of quality and access can be the driving force to solve these problems. As our health care system is reformed, changes need to be built on what works well in the current system, borrowing ideas that work in other countries, to create an accessible, affordable, high-performing system that is focused on value (cost and quality) and sustainability.22

1. Applegate K.E. Continuous quality improvement for radiologists. Acad Radiol. 2004;11(2):155-161.

2. Boston University. AM-PAC computerized adaptive testing manual. Personal computer version (v.1), Boston. Boston University, 2007.

3. Buchanan J.L., Andres P., Haley S., et al. An assessment tool translation study. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24(3):45-60.

4. Buchanan J.L., Andres P., Haley S., et al. Evaluating the planned substitution of the minimum data set-post acute care for use in the rehabilitation hospital prospective payment system. Med Care. 2004;42(2):155-163.

5. Buck C: ICD-9-CM for hospitals, Volumes 1, 2 & 3, Professional Edition, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.

6. CARF: Medical rehabilitation programs. Available at: http://www.carf.org/. Accessed June 15, 2009.

7. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). HHS: Medicare program; prospective payment system for inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Final rule. Fed Reg. 2001;66:41315-41430. Supplement Fed Reg2009

8. Cohen M.M., Eustis M.A., Gribbins R.E. Changing the culture of patient safety: leadership’s role in health care quality improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(7):329-335.

9. Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities: Medical rehabilitation standards manual, Tucson: CARF International, 2009.

10. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century, 2001 National Academies Press.

11. Committee on Redesigning Health Insurance Performance Measures. Payment, and Performance Improvement Programs: IOM report—rewarding provider performance: aligning incentives in Medicare (pathways to quality health care series), Washington, DC,. National Academies Press; 2006.

12. Crahn M.D., Mahoney J.E., Eckman M.H., et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a decision analytic view. JAMA. 1994;272:773-780.

13. Fisher E.S., Wennberg D.E., Stukel T.A., et al. Variations in the longitudinal efficiency of academic medical centers [Health Affairs website]. Published. October 7, 2004. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/abstract/hlthaff.var.19v1. Accessed June 15, 2009

14. Fries J.F., Bruce B., Bjorner J., et al. More relevant, precise, and efficient items for assessment of physical function and disability: moving beyond the classic instruments. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(suppl III):iii16-iii21.

15. Granger C.V., Deutsch A., Russell C., et al. Modifications of the FIM instrument under the inpatient rehabilitation facility prospective payment system. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(11):883-892.

16. Greiner AC, Knebel E: Health professions education: a bridge to quality, Washington, DC, 2004, National Academies Press.

17. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1999.

18. Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

19. Jette A.M., Haley S.M. Contemporary measurement techniques for rehabilitation outcome assessment. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:339-345.

20. Joint Commission Standards. Available at: http://jointcommission.org/. Accessed June 15, 2009.

21. Nagi S.Z. Some conceptual issues in disability and rehabilitation. In: Sussman M.D., editor. Sociology and rehabilitation. Washington, DC: American Sociologic Society, 1965.

22. National Committee for Quality Assurance. The state of health care quality 2008. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2008.

23. National Quality Forum available at http://www.qualityforum.org/. Measuring performance: Consensus Development Process, 2010. Accessed June 15, 2010.

24. Sullivan R., Davis K. Committee staff report to the chairman and ranking member. Use of educational grants by pharmaceutical manufacturers. Committee on Finance, United States Senate. April 2007.

25. Teasell R., Foley N., Bhogal S., et al. Evidence-based practice and setting basic standards for stroke rehabilitation in Canada. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2006;13(3):59-65.

26. Turner-Stokes L. Politics, policy and payment: facilitators or barriers to person-centred rehabilitation? Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(20-21):1575-1582.

27. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. Guide for the uniform data set for medical rehabilitation (adult FIM). Version 4.0. Buffalo, 1993.

28. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation: The guide for the uniform data set for medical rehabilitation (including the FIM™ Instrument), Version 5.1. Buffalo, 1997, UDSmr.

29. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, a division of UB Foundation Activities, Inc: IRF-PAI training manual. Buffalo, 2002, UDSmr.

30. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. The LIFEwareSM System Clinical Guide, Version 1.1. Buffalo, 2004, UDSMR.

31. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. The UDS-PRO® system (including the FIM™ Instrument) Clinical Guide, Version 1.0. Buffalo: UDSMR; 2001.

32. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. The WeeFIM II® Clinical Guide, Version 6.0. Buffalo: UDSMR; 2006.

33. Weiss KB: Safe, quality care is a goal we all share. ABMS Patient Safety Improvement Program Newsletter October, 2008.

34. Wenneberg J.E., O’Connor A.M., Collins D., et al. Extending the P4P agenda. Part 1: how Medicare can improve patient decision making and reduce unnecessary care. Health Aff. 2007;26(6):1564-1574.

35. Wilensky G. Developing a center for comparative effectiveness information. Health Aff. 2006;25(6):W572-W585.

36. Wilkerson D.L. Accreditation and the use of outcomes-oriented information systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(suppl V):S31-S35.

37. World Health Organization. International classification of function, disability, and health: ICF. Geneva: WHO; 2001.