Chapter 11 Pustular eruptions

1. How does a pustule differ from a vesicle or bulla?

A pustule is a purulent vesicle or bulla. Whereas a vesicle contains clear or translucent fluid, a pustule is filled with neutrophils or, less commonly, eosinophils. Pustules are one of the primary lesions in skin. Most pustular eruptions begin as pustules, but others may pass through a transitory stage in which they appear vesicular (vesiculopustules).

2. How are pustules classified?

Pustules may be classified on the basis of where the acute inflammatory cells accumulate (e.g., subcorneal, follicular), pathogenesis (e.g., infectious, autoimmune), predominant inflammatory cells (e.g., neutrophils, eosinophils), and clinical presentation (Table 11-1). Pustules may be unilocular or multilocular.

3. What is the most common pustular skin eruption?

Acne vulgaris, although not all lesions in this condition are pustular (Fig. 11-1). The infectious pustular eruptions are also common (see Chapter 27).

4. Name the different types of pustular psoriasis. How do they differ?

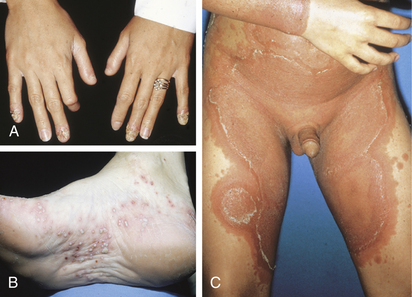

Pustular psoriasis may be broadly subdivided into localized and generalized forms. Localized pustular psoriasis may occur on any site and may also occur within plaques of classic psoriasis. Distinctive variants include acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau (Fig. 11-2A), which is characterized by pustules and crusting of the distal fingers and toes, and localized pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles (Fig. 11-2B). It is unclear whether pustular eruptions confined to the palms and soles represent a form of localized psoriasis or a different disease called pustular bacterid. Variants of generalized pustular psoriasis include generalized pustular psoriasis of von Zumbusch, exanthematic generalized pustular psoriasis, and impetigo herpetiformis. The von Zumbusch variant presents as generalized pustules in patients with preexisting plaque-type psoriasis or erythrodermic psoriasis. Exanthematic generalized pustular psoriasis arises suddenly without preceding psoriasis (Fig. 11-2C). Impetigo herpetiformis is associated with pregnancy. Hypocalcemia is also frequently present.

5. Do any factors precipitate generalized pustular psoriasis?

The most important inciting factor is the administration of systemic corticosteroids. In a study of 104 patients, corticosteroids were implicated as the precipitating factor in 37 patients (36%). This association is one of the primary reasons that psoriasis is not treated with systemic corticosteroids. Less common precipitating factors included infection (13%), hypocalcemia (9%), pregnancy (3%), and other drugs (e.g., terbinafine).

| PATHOGENESIS | SITE OF ACCUMULATION |

|---|---|

| Autoimmune | |

| IgA pemphigus | Subcorneal |

| Infectious | |

| Arthropod reactions | Intraepidermal |

| Candidiasis | Subcorneal |

| Furuncle/carbuncle | Follicular |

| Impetigo | Subcorneal |

| Hot tub (pseudomonal) folliculitis | Follicular |

| Kerion (tinea capitis) | Follicular |

| Pityrosporum folliculitis | Follicular |

| Vaccinia infection/vaccination | Intraepidermal |

| Inherited | |

| Pustular psoriasis | Subcorneal, intraepidermal |

| Reiter’s syndrome | Subcorneal, intraepidermal |

| Drug eruptions | |

| Acneiform drug-induced eruptions | Follicular |

| Toxic erythema with pustules | Subcorneal |

| Halogenodermas | Intraepidermal |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Acne necrotica miliaris | Follicular |

| Acne vulgaris | Follicular |

| Erythema toxicum neonatorum | Follicular |

| Folliculitis decalvans | Follicular |

| Infantile acropustulosis | Subcorneal, intraepidermal |

| Miliaria pustulosa | Sweat duct |

| Pustular bacterid | Intraepidermal |

| Rosacea | Follicular |

| Subcorneal pustular dermatosis | Subcorneal |

| Transient neonatal pustular dermatosis | Subcorneal |

Figure 11-1. Gram-negative pustular acne vulgaris.

(Courtesy of the Fitzsimons Army Medical Center teaching files.)

6. Is pustular psoriasis treated differently than classic plaque-type psoriasis?

Most treatments that are used on classic plaque-type psoriasis can also be used for the management of pustular psoriasis. The retinoids, especially acitretin, are particularly effective in pustular psoriasis and are the treatment of choice for generalized pustular psoriasis. More recently, isolated cases have been successfully treated with topical biologic agents such as tacrolimus or parental biologic agents such as infliximab and adalimumab.

7. What is pustular bacterid?

Pustular bacterid (of Andrews) is a controversial clinical eruption. Most dermatologists consider it to be a form of pustular psoriasis localized to the palms and soles. As originally defined by Andrews, pustular bacterid is a pustular eruption of the palms and soles in which the patient has no history or other clinical signs of psoriasis. The lesions are induced by low-grade bacterial infection in occult or evident foci, such as the teeth, tonsils, or gallbladder. The pustular eruption totally resolves with eradication of the infection. A later study has noted that injected Candida antigen aggravated up to 37% of patients with this disorder, suggesting that this phenomenon may not be restricted to bacterial infections. The recent recognition of bacterial “superantigens” provides a possible immunologic mechanism for induction of this disorder.

Stevens DM, Ackerman AB: On the concept of bacterids (pustular bacterid, Andrews), Am J Dermatopathol 6:281–286, 1984.

8. Why do some consider pustular bacterid a form of localized pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles?

The argument is based on the observation that some patients with pustular eruptions of the palms and soles also have typical psoriasis elsewhere. The clinical appearance and histologic findings of the palmar lesions are identical to those of pustular bacterid. Some dermatologists prefer the term palmar and plantar pustulosis as a noncommittal name for this entity.

9. What is subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease)?

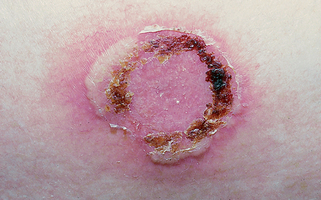

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis is a rare, benign, chronic, relapsing dermatosis that was described by Sneddon and Wilkinson in 1956. It most commonly affects middle-aged women, although any age group, including children, may be affected. The lesions typically occur in the flexural and intertriginous areas, where they present as superficial vesiculopustules or pustules that often assume annular or gyrate patterns. The lesions may demonstrate peripheral extension and resolve with variable crusting and scaling. Typically, patients are otherwise healthy, but there are isolated case reports of an associated seronegative rheumatoid-like arthritis.

10. Discuss the pathogenesis of subcorneal pustular dermatosis.

The pathogenesis of subcorneal pustular dermatosis is unknown; although some cases have been associated with plasma cell dyscrasias. Even the nosology is controversial. While many authors accept this condition as a distinct entity, a few consider it to be synonymous with, or a variant of, pustular psoriasis. Histologically, both entities demonstrate a subcorneal vesicle filled with neutrophils. The strongest points against the relationship of subcorneal pustular dermatosis and psoriasis are that the former has a distinct clinical presentation, patients do not have preceding plaque-type psoriasis, and they are not likely to develop classic psoriasis during the course of their disease. Some drugs such as lithium carbonate may exacerbate subcorneal pustular dermatosis by increasing neutrophil migration into lesions.

11. How is subcorneal pustular dermatosis treated?

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis cannot be cured, but it can be managed. The disease is uncommon enough that good therapeutic studies comparing different treatment modalities are not available. Anecdotal reports have described excellent therapeutic results with dapsone and acitretin. Less frequently used therapies include oral prednisone, topical corticosteroids, sulfapyridine, vitamin E, and ultraviolet B therapy.

12. What is superficial IgA pemphigus?

Recently, it has been demonstrated that some cases of what were formerly classified as subcorneal pustular dermatosis may demonstrate intraepidermal IgA between the keratinocytes. Most authorities feel that cases with intraepidermal IgA on direct immunofluorescence should be reclassified as superficial IgA pemphigus (Fig. 11-3). It has been demonstrated that the IgA autoantibodies are directed against desmocollin 1 and possibly desmocollins 2 and 3, which are molecules that are important for normal adhesion between keratinocytes.

13. What are the cutaneous findings in reactive arthritis (Reiter’s disease)?

The classic triad of reactive arthritis (Reiter’s disease) consists of nongonococcal urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis. However, this triad is present in only 40% of the cases at the time of presentation, and the mucocutaneous findings are helpful in establishing the diagnosis. The mucocutaneous findings include a nonspecific stomatitis, nail changes (subungual hyperkeratosis and onycholysis), circinate balanitis, and keratoderma blennorrhagicum. Keratoderma blennorrhagicum is present in about one third of cases and presents as pinpoint erythematous papules that progress to pustules and hyperkeratotic papules and plaques. These are most commonly seen on the bottom of the feet but may also occur on the scalp, elbows, knees, buttocks, and genitalia. Histologically, the findings are identical to the pustules seen in pustular psoriasis.

14. Which drugs are commonly associated with pustular drug eruptions?

Drugs may produce different patterns of pustular drug eruptions, including aggravation of preexisting pustular eruptions such as psoriasis or subcorneal pustular dermatosis. Primary pustular drug eruptions can be classified as acneiform, halogenodermas, and toxic erythema with pustules.

• Acneiform drug eruptions: Systemic corticosteroids (steroid acne), phenytoin, lithium, iodides, bromides, isoniazid (Fig. 11-4)

• Halogenodermas: Iodides, bromides, and fluorides may produce both acneiform drug eruptions and nonfollicular pustules (Fig. 11-5)

• Drug-induced toxic erythema with pustules (acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis): A drug eruption that presents as fever, malaise, and diffuse erythema studded with small pustules; caused by numerous medications including co-trimoxazole, erythromycin, hydroxychloroquine, streptomycin, terbinafine, and cephalosporins

15. What is acne necrotica miliaris?

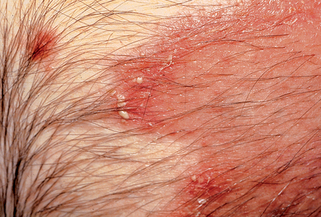

This chronic folliculitis of the scalp, which primarily affects middle-aged men, presents as follicular-based pustules that quickly develop into perifollicular crusts and scale. The eruption may be asymptomatic or pruritic. If the lesions are pruritic, secondary excoriations may predominate. Acne necrotica miliaris does not result in permanent scarring or hair loss. Most patients respond to low-dose tetracycline, which may need to be continued for years.

16. What is folliculitis decalvans?

Folliculitis decalvans (Quinquaud’s disease) is a rare, scarring alopecia of unknown etiology. Clinically, it presents as follicular-based pustules that may assume annular or circinate configurations. The pustules rapidly form crusts; in many patients, the crusts may predominate. The hairs are permanently lost, leaving patches of atrophic hairless skin. Treatment is generally unsatisfactory; topical corticosteroids and oral antibiotics are typically used. Anecdotal reports have described isolated success with oral rifampin or oral zinc sulfate.

17. Discuss the pathogenesis of miliaria pustulosa.

All forms of miliaria result from the retention of sweat secondary to occlusion of the sweat ducts. The pathogenesis of miliaria pustulosa is not entirely understood, but it is believed that heat and occlusion result in the proliferation of surface bacteria that produce toxins that damage the acrosyringium (intraepidermal portion of the eccrine sweat duct). Depending on the level of occlusion, different patterns of disease are produced. If significant numbers of neutrophils are attracted to the acrosyringium, a flaccid pustule develops, producing miliaria pustulosa. If the disease is less severe or the inflammatory response muted, then only an erythematous papule is present, producing the clinical lesion called miliaria rubra (heat bumps, prickly heat). If the damage to the acrosyringium is entirely mechanical, such as occurs following a sunburn, the inflammatory response is minimal and small superficial vesicles are formed at the acrosyringium, producing the variant referred to as miliaria crystallina.

18. How is miliaria pustulosa treated?

Once miliaria pustulosa has developed, there is no satisfactory treatment except removing the patient from the hot and humid environment. Occlusive wear that may have aggravated the condition should also be eliminated. Anecdotally, some dermatologists have tried weak solutions of salicylic acid to produce exfoliation or tape stripping of the stratum corneum to remove the obstruction to sweating, but there are no studies to document the efficacy of these treatments. Some patients may require weeks or even months to establish normal sweating after severe attacks.

19. What is the differential diagnosis of a pustular eruption in a neonate?

Key Points: Neonatal Pustular Eruptions

2. The pathogenesis of neonatal pustular eruptions includes hormonal (neonatal acne), infectious (herpes simplex infection, candidiasis, staphylococcal infection, congenital syphilis), occlusive (miliaria rubra), or idiopathic (transient neonatal pustular melanosis, erythema toxicum neonatorum).

4. Problematic cases should be evaluated by diagnostic studies to include examining the blister contents with Wright’s stain to look for the primary inflammatory cell type (neutrophils versus eosinophils) and balloon cells to exclude herpes virus infection and Gram stains to rule out bacteria and Candida infection.

20. How do erythema toxicum neonatorum and transient neonatal pustular melanosis differ?

Erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN) and transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPT) are both benign vesiculopustular disorders of unknown etiology that present during the first few days of life. ETN does not demonstrate a racial predilection and is very common, with up to 20% of neonates being affected. Clinically, it usually presents as macular erythema that usually affects the face initially; approximately 10% to 20% of cases develop pustules within the center of the areas of macular erythema. Biopsies of the pustules demonstrate an acute superficial folliculitis composed primarily of eosinophils. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present in 20% of cases. The lesions resolve without permanent sequelae in 7 to 10 days. Epidemiologically, TNPT differs from ETN in that it occurs in about 5% of black neonates but in <1% of white neonates. Clinically, it presents as vesiculopustules that are not associated with surrounding erythema. The vesiculopustules resolve within 48 hours and are followed by hyperpigmented macules that may take 3 months to resolve. In contrast to ETN, biopsies demonstrate subcorneal pustules that are not follicular based, and the primary inflammatory cells are neutrophils. Peripheral eosinophilia is absent. Both conditions are benign and self-limited. Treatment is not recommended.

21. What is infantile acropustulosis?

Infantile acropustulosis, also referred to as acropustulosis of infancy, is an inflammatory disease first described in 1979. Most case reports have been in black infants from the southern United States, but it has also been reported in other racial groups and countries including Scandinavia. Clinically, the condition is characterized by recurrent crops of 1- to 2-mm intensely pruritic vesiculopustules on the extremities (Fig. 11-6). Histologically, there are well circumscribed intraepidermal pustules filled with neutrophils. Most cases spontaneously resolve by 2 years of age.

23. What is the best treatment of infantile acropustulosis?

Nothing works very well. The disease is self-limited; it usually disappears spontaneously by age 2 years. Patients with severe pruritus can be treated with high doses of antihistamines. Some patients respond to potent topical corticosteroids, while rare patients may require treatment with oral dapsone.

Figure 11-6. Infantile acropustulosis demonstrating typical, pruritic acral pustules in a black child.

Mancini AJ, Frieden IJ, Paller AS: Infantile acropustulosis revisited: history of scabies and response to topical corticosteroids, Pediatr Dermatol 15:337–341, 1998.