221 Pursuit of Performance Excellence

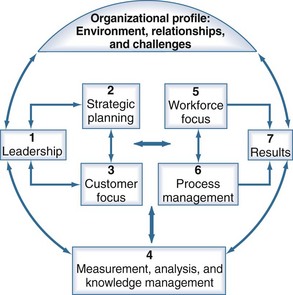

Organizations consist of numerous parts, systems, and functions all operating and, ideally, collaborating to produce an end result, one that is not always desired. Unlike the organs of the human body, in healthcare delivery, different components often struggle to operate in a coordinated and symbiotic fashion. Systems such as pharmacy, lab billing, ICU, operating room, emergency department, internal medicine, surgery, and graduate medical education programs frequently operate independently without the coordination necessary to produce reliably integrated operations. The parts seem more independent than interdependent, more competitive than cooperative, and more focused on their own efforts than on the results of the whole. Whereas each part has to remain viable and effective in order to contribute to the overall goals and purpose of the organization, all parts must operate in harmony for superior performance to be achieved and maintained. Using the Baldrige Performance Excellence Program (BPEP or Baldrige) as a framework (Figure 221-1), this chapter provides guidance on how to design and manage the ICU to improve patient outcomes and be a great part of the larger hospital system. The Baldrige framework is elaborate, and a full presentation is beyond the scope of this chapter. A complete guide to the framework can be found at www.baldrige.org.

Figure 221-1 Baldrige healthcare criteria for performance excellence framework: a systems perspective.

(Adapted from www.baldrige.org.)

Background and Overview

Background and Overview

Differentiation of High Performance Versus Average Performance or Scoring Guidelines

The Baldrige Intensive Care Unit

The Baldrige Intensive Care Unit

Category 1: Leadership

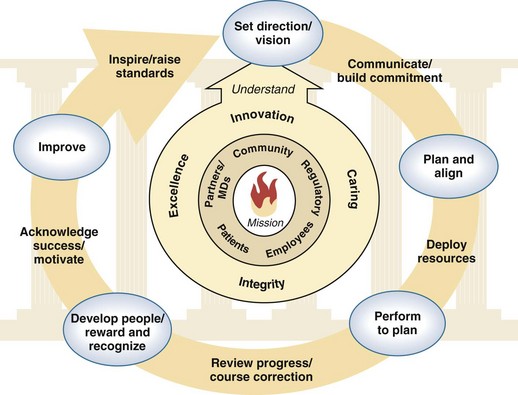

The criteria for leadership are instructive as they relate to ICUs and are likely very different from the current approach. Within the ICU, opportunities exist for the leadership team to become a more instructive leadership system (Figure 221-2) and promote a unit that demonstrates repeatable and fully deployed process across all areas of delivering ICU care. The leadership team ensures consistency of care across boundaries, incorporates and supports continuous cycles of improvement and/or innovation, and strategically aligns with the overall goals and objectives of the hospital.

Category 2: Strategic Planning

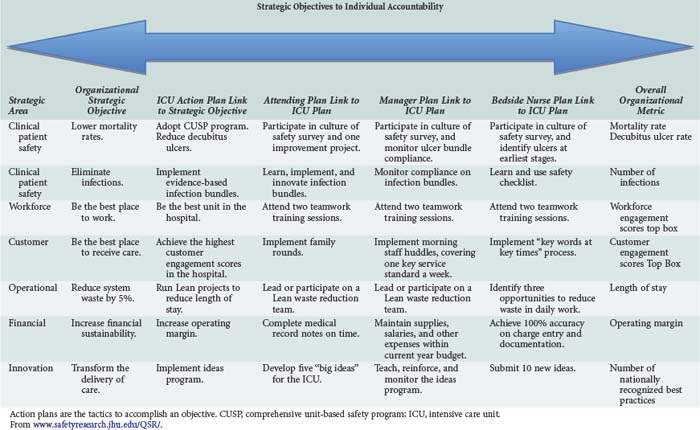

Crucial to this process is how the ICU communicates the strategic plan to the entire unit. This plan should not only be known by the leadership group; in high performing organizations, every employee knows what’s going on and how they fit in to the overall work. In our example, the ICU provided every person with a laminated color card listing the unit’s strategic objectives and key measures for performance. In addition, each employee was issued a cascade plan to guide work processes, goal setting, and professional development. These cascade plans list and strategically link and align the objectives of the hospital, the ICU, and the individual. The cascade plan is used quarterly as a performance assessment tool (Table 221-1).

Category 4: Measurement, Analysis, and Knowledge Management

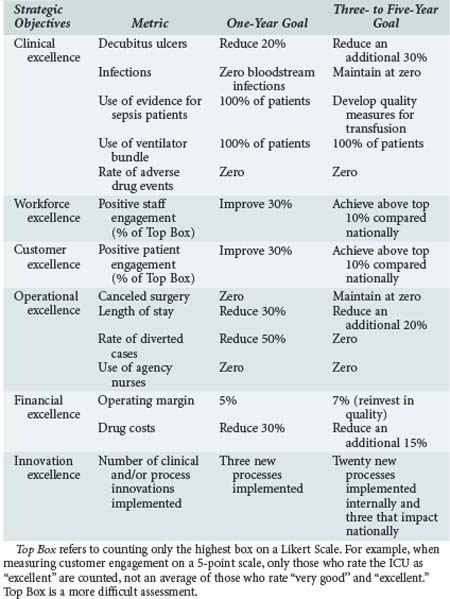

The ICU’s key measures cascade down from the hospital’s overall goals, which in this example fall into five areas of focus: clinical performance, customer engagement, workforce engagement, operational performance, and financial performance (Table 221-2). During the strategic planning process, the leadership group, using input from the workforce, identified three or four leading indicators within each area that directly predicted the achievement of the key objectives and goals of the unit. These were then validated through a set of criteria asking certain questions:

As another example, the leadership group set a goal of zero catheter-related infections. Data reviewed at the monthly leadership meeting revealed the incidence of bloodstream infections to be increasing and the rate of infection to be well above that of best-in-class, not to mention previous performance levels. The leadership group identified this as an opportunity for improvement and elected to convene a multidisciplinary team to reduce the number of bloodstream infections. This group replicated the approach used in the Michigan Keystone ICU study that virtually eliminated these infections throughout the state.1 As part of this process, the leadership group communicated to the entire unit that reducing the number of bloodstream infections was a key strategic objective and would be reviewed each month. The bloodstream infection reduction team used the weekly infection control data collected and implemented interventions such as a catheter checklist on line carts, empowering the nurses to stop catheter placement if physicians did not comply with the checklist items, investigating every infection as a defect, and training on teamwork and communication for the nurses and physicians. Continuous cycles of improvement were implemented, and the bloodstream infection trend data demonstrated a progressive reduction. Work systems and processes related to catheter insertions became standardized in the unit and were ultimately communicated through the organization via a new policy and monitored for adherence.

Category 6: Process Management

For example, it is important for the ICU leadership group to create work systems that deliver care based on the needs of all ICU constituents—patients, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and so forth—and align with the goals and objectives of the unit. The question needs to be asked: How do our processes create value for those we serve, and how do we know we have been successful? Using this mantra as a guide, the leadership group in our ICU example aligned the work processes with the unit to continuously meet the expectations of each ICU customer segment. This involved a number of approaches; however, the ultimate deliverable was a system of work designed to achieve the key requirements (categories 2 and 3) identified in the ICU strategic plan. Data indicated that the lack of clarity around a given patient care plan was causing increased errors and longer stays. Using the goal of reducing harm and improving teamwork and communication among the unit’s healthcare professionals (as stated in the strategic plan), the leadership group tested and implemented an evidence-based checklist developed by Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, and colleagues that incorporates a multidisciplinary team approach to making rounds.2 During these rounds, a daily goals sheet is used to communicate the care plan for the particular patient to the multidisciplinary team, consisting of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and others. The use of this checklist over time led to a reduction in length of stay and adverse drug events, and both nurse and physician teamwork and satisfaction scores have improved. This mechanism is guided by several criteria in this Baldrige category dealing with the inclusion of patient expectations, testing to prevent errors, and achieving better performance by reducing variation in care. Unexplained and avoidable variation in care is one of the principal causes of failure in healthcare process and outcomes.

Conclusion

Conclusion

ICUs are places of emotion, extraordinary science, compassion, and sometimes high drama in the conflict between disease and injury and the will to live. Optimally, they are designed to enable the uniquely talented professionals who dedicate their careers to healing at the highest levels. Yet experience has proved with alarming frequency that the enormous and sometimes even heroic good that is accomplished is marred by what could or should have been done. Patients enter our ICUs trusting that we will do what is needed, correctly and with compassion. There is only one standard of care acceptable—no excuses are permitted. The Baldrige program, the nation’s formally adopted approach to excellence, is not just another improvement tool. Rather, it is a framework of systematic elements that are woven together to achieve the singular aim of excellence (Table 221-3). The Baldrige framework inspires leaders to create the culture through which every employee involved in the care of the very ill performs to his or her potential. It sets forth the foundation through which leaders of ICUs can track and achieve results that are comprehensive, balanced, and presented in the context of true world-class performance. It probes the leadership structure to consider how key elements of organizational success are accomplished, how they are systematically deployed throughout the unit, how continuous improvement is a system property, and how all the work is aligned with the unit’s mission, vision, and values.

TABLE 221-3 Seven Categories of Healthcare Criteria for Performance Excellence and Related Key Questions

| Categories | Key Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Leadership | How does the ICU senior leadership guide the unit through its governance system and organizational performance reviews? How does the ICU leadership ensure sustainability of all key processes at the highest levels of performance, considering innovation? |

| 2. Strategic planning | How does the ICU establish its strategic objectives and action plans, and how are they deployed and measured across the unit? |

| 3. Customer focus | How does the ICU determine customer/patient requirements, expectations, and preferences, and how does the ICU build relationships with its patients to increase customer/patient engagement? |

| 4. Measurement, analysis, and knowledge management | How does the ICU select, gather, analyze, manage, and improve its measurement system, and how is this knowledge shared, transferred, and communicated throughout the unit? |

| 5. Workforce focus | How does the ICU’s work system, staff learning, and staff motivation enable all workforce members to develop and utilize their full potential in alignment with the unit’s strategic objectives, goals, and action plans? How do you determine the key factors of engagement for each workforce segment? What are they? |

| 6. Operations focus | How does the ICU’s process management system, including both key processes and support processes, create value for the patient and staff? How do you know? |

| 7. Organizational performance results | How do the ICU’s results compare to competitors and industry benchmarks over time? Are they reflective of the ICU’s strategic objectives? |

Key Points

Pronovost P, Goeschel CA, Colantuoni E, Watson S, Lubomski LH, Berenholtz SM, et al. Sustaining reductions in catheter related bloodstream infections in Michigan intensive care units: observational study. BMJ. 2010;340:c309.

National Institute for Standards and Technology. Health care criteria for performance excellence. NIST. 2010. Available at: www.baldrige.org/

This guide provides the actual Baldrige criteria used by the national program and organizations.

Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, et al. Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care. 2003;18:71-75.

1 Pronovost PJ, Goeschel CA, Colantuoni E, Watson S, Lubomski LH, Berenholtz SM, et al. Sustaining reductions in catheter related bloodstream infections in Michigan intensive care units: observational study. BMJ. 2010;340:c309.

2 Pronovost P, Berenholtz S, Dorman T, et al. Improving communication in the ICU using daily goals. J Crit Care. 2003;18:71-75.