Chapter 58

Pulmonary Hypertension

1. What is the hemodynamic criteria used to define pulmonary arterial hypertension?

2. What are the usual physical findings in patients with pulmonary hypertension?

The most common findings on physical examination include the following:

Loud pulmonic valve closure sound (P2)

Loud pulmonic valve closure sound (P2)

Murmur of tricuspid regurgitation (a systolic murmur over the left lower sternal border)

Murmur of tricuspid regurgitation (a systolic murmur over the left lower sternal border)

Murmur of pulmonic insufficiency (a diastolic murmur over the left sternal border)

Murmur of pulmonic insufficiency (a diastolic murmur over the left sternal border)

Jugular venous distension (indicating elevated central venous pressures)

Jugular venous distension (indicating elevated central venous pressures)

At the Fourth World Conference on Pulmonary Hypertension (held in Dana Point, Calif., in 2008), the term familial PAH was replaced by hereditary PAH, and schistosomiasis and chronic hemolytic anemia were added to Group 1 PAH. Current classification is outlined in Box 58-1. Pulmonary hypertension is classified as pulmonary arterial hypertension (Group 1), pulmonary hypertension resulting from left heart disease (Group 2), pulmonary hypertension resulting from lung diseases and/or hypoxia (Group 3), chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) (Group 4), and pulmonary hypertension with unclear multifactorial mechanisms (Group 5).

4. Is pulmonary hypertension a genetic disease?

About 6% of patients with PAH have hereditary PAH. Mutations in the gene encoding bone morphogenetic receptor 2 (BMPR2) were found in approximately 70% of families with hereditary PAH and in 20% to 30% of patients with idiopathic PAH. Due to incomplete penetrance, most patients with this mutation never develop the disease. A subject with a mutation has a 10% to 20% estimated lifetime risk of acquiring PAH.

5. What should the clinical evaluation for possible pulmonary hypertension include?

Patients with no clues to the cause on history or physical examination should be given a broad, detailed evaluation; patients with a suspected secondary cause should receive a focused evaluation to verify that cause, followed by the broad evaluation if necessary. In addition to these tests, arterial blood gases and pulmonary angiography may be indicated. If undertaken, pulmonary angiography should be performed by a radiologist experienced in working with pulmonary hypertension patients. Conditions and symptoms associated with pulmonary hypertension are listed in Table 58-1.

TABLE 58-1

CONDITIONS AND SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED WITH PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

| CATEGORY | CONDITIONS OR SYMPTOMS |

| Heart Failure (Systolic or Diastolic) | Dyspnea, exercise intolerance, angina, prior myocardial infarctions, systemic hypertension, valvular heart disease |

| Current Smoking | Shortness of breath, “smokers cough”, hypoxia |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | Snoring, excessive somnolence, witnessed apneic episodes |

| Autoimmune Diseases | History of skin changes, arthritis, gastrointestinal problems, and renal disease |

| Chronic Thromboembolic Disease | Prior history of pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and genetic or acquired hypercoagulable conditions |

| Drug History | Illicit drug abuse, prior anorexiant use, and herbal products |

| Chronic Liver Disease | History of jaundice, ascites, chronic viral hepatitis, and alcohol abuse. Symptoms of portal hypertension, including abdominal distention and gastrointestinal bleed |

| HIV Infection | Risky sexual behavior, intravenous drug abuse and needle sharing |

| Congenital Diseases | History of congenital heart disease and intracardiac shunts, family history of sickle cell disease |

An assessment of the patient’s functional status and six-minute walk test should also be performed. Table 58-2 lists the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of functional status of patients with pulmonary hypertension.

TABLE 58-2

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION CLASSIFICATION OF FUNCTIONAL STATUS OF PATIENTS WITH PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

| CLASS | DESCRIPTION |

| I | Patients with pulmonary hypertension but without resulting limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue dyspnea or fatigue, chest pain, or near syncope. |

| II | Patients with pulmonary hypertension resulting in slight limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Ordinary physical activity causes undue dyspnea or fatigue, chest pain, or near syncope. |

| III | Patients with pulmonary hypertension resulting in marked limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest. Less than ordinary activity causes undue dyspnea or fatigue, chest pain, or near syncope. |

| IV | Patients with pulmonary hypertension with inability to carry out any physical activity without symptoms. These patients manifest signs of right-sided heart failure. Dyspnea or fatigue may even be present at rest. Discomfort is increased by any physical activity. |

Modified from Rubin LJ: Diagnosis and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, Chest 126:7S-10S, 2004.

6. Which connective tissue diseases most commonly cause pulmonary hypertension?

Systemic sclerosis (especially CREST syndrome)

Systemic sclerosis (especially CREST syndrome)

Mixed connective tissue disease

Mixed connective tissue disease

7. What population group is most commonly affected by PAH?

Although PAH occurs in both genders and virtually all age groups, it has a tendency to affect females. The modern U.S. PAH patient population is older (mean age at diagnosis is 47 years) and has a female preponderance. According to a French registry, female-to-male predominance is 1.7:1, whereas according to the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL) data, the female-to-male ratio is 3.6:1. REVEAL registry is a multicenter, observational U.S. based registry of PAH patients initiated in 2006 and data from this registry shows that factors associated with increased mortality include men older than 60 years of age, hereditary PAH, pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) greater than 32 Woods units, portopulmonary hypertension, and New York Heart Association (NYHA)/WHO functional class IV (Table 58-3).

TABLE 58-3

HEMODYNAMIC DEFINITION OF PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

| PULMONARY HYPERTENSION | MEAN PAP ≥ 25 mm Hg | PH Group |

| Precapillary pulmonary hypertension | Mean PAP ≥ 25 mm Hg PCWP ≤ 15 mm Hg Cardiac output normal or reduced |

Group 1. PAH Group 3. PH due to lung disease Group 4. CTEPH Group 5. PH multifactorial etiology |

| Postcapillary pulmonary hypertension | Mean PAP ≥ 25 mm Hg PCWP > 15 mm Hg Cardiac output normal or reduced or increased |

Group 2. PH due to left heart disease |

8. Is surgical therapy now an option for patients with pulmonary hypertension secondary to chronic recurrent thromboembolism?

9. What is the average survival outlook for a PAH patient?

According to the National Institutes of Health Registry on Primary Pulmonary Hypertension, in the past, the median survival was approximately 2.8 years from the date of diagnosis. With the availability of new therapeutic modalities, survival has improved. According to the French registry, the 1-year survival is 88% and according to REVEAL registry, the 1-year survival is 85% and 5-year survival is 57%.

10. What is considered conventional therapy for patients with PAH?

Conventional therapy for patients with PAH includes the following:

Supplemental oxygen as needed to maintain an oxygen saturation of at least 91%

Supplemental oxygen as needed to maintain an oxygen saturation of at least 91%

Diuretics if the patient has clinically significant edema or ascites

Diuretics if the patient has clinically significant edema or ascites

11. Are calcium channel blockers used in the treatment of PAH?

12. What is considered a favorable response to acutely administered vasodilators?

13. What are the approved therapies to treat PAH?

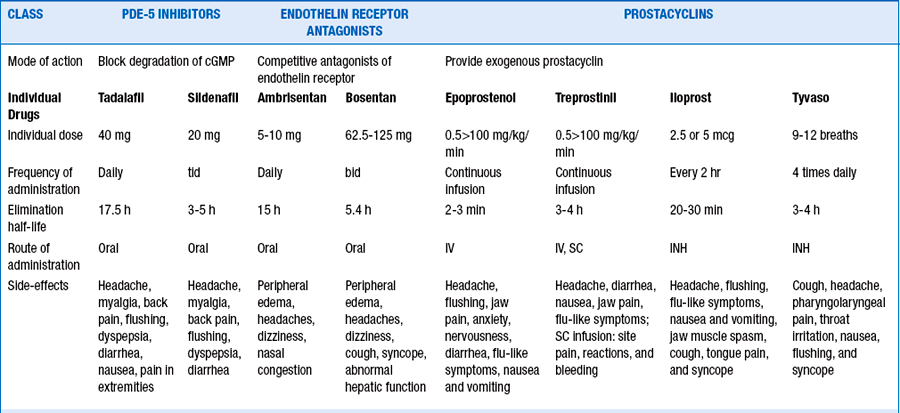

Currently nine U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies target the three identified pathways involved in the pathogenesis of PAH. Table 58-4 lists the FDA-approved drugs to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Endothelin receptor antagonists. Endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor, acts as a mitogen, induces fibrosis, and leads to the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. The effects of endothelin-1 are mediated through the activation of ETA and ETB receptors. Differential activation of ETA and ETB receptors leads to the vasoconstricting and vascular proliferative actions of endothelin-1. Bosentan is a dual endothelin receptor blocker, whereas ambrisentan is an ETA blocker.

Endothelin receptor antagonists. Endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor, acts as a mitogen, induces fibrosis, and leads to the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. The effects of endothelin-1 are mediated through the activation of ETA and ETB receptors. Differential activation of ETA and ETB receptors leads to the vasoconstricting and vascular proliferative actions of endothelin-1. Bosentan is a dual endothelin receptor blocker, whereas ambrisentan is an ETA blocker.

Prostacyclins. Prostacyclin is the main product of arachidonic acid in the vascular endothelium. By the production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), prostacyclin promotes pulmonary vascular relaxation and inhibits growth of smooth muscle cells. In addition, prostacyclin is a powerful inhibitor of platelet aggregation. There are three prostacyclins approved for therapy; these include intravenous, subcutaneous, and inhaled treprostinil, intravenous epoprostenol, and inhaled iloprost.

Prostacyclins. Prostacyclin is the main product of arachidonic acid in the vascular endothelium. By the production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), prostacyclin promotes pulmonary vascular relaxation and inhibits growth of smooth muscle cells. In addition, prostacyclin is a powerful inhibitor of platelet aggregation. There are three prostacyclins approved for therapy; these include intravenous, subcutaneous, and inhaled treprostinil, intravenous epoprostenol, and inhaled iloprost.

Phosphodiestersae-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors. Phosphodiestersae-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors block the breakdown of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in the vascular endothelium, resulting in increased activity of endogenous nitric oxide that enhances pulmonary vasodilation. Sildenafil and tadalafil are the PDE-5 inhibitors approved to treat PAH in U.S.

Phosphodiestersae-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors. Phosphodiestersae-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors block the breakdown of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in the vascular endothelium, resulting in increased activity of endogenous nitric oxide that enhances pulmonary vasodilation. Sildenafil and tadalafil are the PDE-5 inhibitors approved to treat PAH in U.S.

14. What are the complications associated with prostanoid therapy?

Because prostanoids are nonselective vasodilators, a common complication is systemic hypotension. Other commonly reported side effects include flushing, headaches, nausea, diarrhea, leg pain, and jaw pain. Because intravenous administration of prostacyclin requires central venous access, line infections (especially gram negative sepsis related to treprostinil use) and catheter-associated thrombosis are common. Proper care of the catheter and anticoagulation help lessen these risks, but there is still the chance for significant and life-threatening complications.

15. How do I treat the pulmonary hypertension associated with CREST syndrome?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Barst, R.J., Rubin, L.J., Long, W.A., et al. A comparison of continuous intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) with conventional therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension. The Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:296–302.

2. Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al: Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 122:164–172.

3. Channick, R.N., Simonneau, G., Sitbon, O., et al. Effects of the dual endothelin-receptor antagonist bosentan in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2001;358:1119–1123.

4. Galiè, N., Brundage, B.H., Ghofrani, H.A., et al. Tadalafil therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2009;119:2894–2903.

5. Galiè, N., Ghofrani, H.A., Torbicki, A., et al. Sildenafil citrate therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2148–2157.

6. Galiè, N., Olschewski, H., Oudiz, R.J., et al. Ambrisentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the ambrisentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, efficacy (ARIES) study 1 and 2. Circulation. 2008;117:2966–2968.

7. Humbert, M., Sitbon, O., Chaouat, A., et al. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in France: results from a National Registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1023–1030.

8. McGoon, M., Gutterman, M., Steen, V., et al. Screening, early detection, and diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2004;126:14S–34S.

9. McLaughlin, V.V., Archer, S.L., Badesch, D.B., et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1573–1619.

10. Miyamoto, S., Nagaya, N., Satoh, T., et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Comparison with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:487–492.

11. Oudiz, R.J. Primary Pulmonary Hypertension. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/301450-overview.. Accessed March 26, 2013

12. Simonneau, G., Barst, R.J., Galiè, N., et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:800–804.

13. Simonneau, G., Robbins, I.M., Beghetti, M., et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S43–S54.

14. Sitbon, O., Humbert, M., Jais, X., et al. Long-term response to calcium channel blockers in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2005;111:3105–3111.

15. Sitbon, O., Humbert, M., Nunes, H., et al. Long-term intravenous epoprostenol infusion in primary pulmonary hypertension: prognostic factors and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:780–788.

) scan, hypercoagulable work-up (if indicated), electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram.

) scan, hypercoagulable work-up (if indicated), electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram.

scan suggestive of CTEPH must have a pulmonary angiogram for accurate diagnosis and assessment of resectability of the thrombi. It is now possible to surgically remove an organized thrombus from the proximal pulmonary arteries of such patients. Operative mortality is low in most experienced centers, and lifelong anticoagulation and inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement are essential for such patients.

scan suggestive of CTEPH must have a pulmonary angiogram for accurate diagnosis and assessment of resectability of the thrombi. It is now possible to surgically remove an organized thrombus from the proximal pulmonary arteries of such patients. Operative mortality is low in most experienced centers, and lifelong anticoagulation and inferior vena cava (IVC) filter placement are essential for such patients.