CHAPTER 101 Pulmonary Hemorrhage and Vasculitis

A large number of conditions may result in pulmonary hemorrhage (Table 101-1). Broadly speaking, pulmonary hemorrhage may originate in the airways or lung parenchyma. Airway-related pulmonary hemorrhage is commonly the result of bronchitis, bronchiectasis, or malignancy, whereas parenchymal hemorrhage may result from pulmonary infarction, necrotizing pneumonias, toxic inhalational injury, malignancy, or causes of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, with or without pulmonary vasculitis.

TABLE 101-1 Differential Diagnosis of Pulmonary Hemorrhage

| Cause | Features |

|---|---|

| Airway | |

| Parenchyma | |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage with capillaritis | |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage without capillaritis | |

| Other | Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation |

DIFFUSE ALVEOLAR HEMORRHAGE

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is present when the cause of the hemorrhage primarily affects the alveolar capillary surface. Causes of DAH may be divided into conditions associated with inflammation of the pulmonary capillaries, referred to as capillaritis, and those without capillaritis, so-called bland DAH (see Table 101-1). Pulmonary capillaritis refers to alveolar interstitial inflammation consisting of neutrophil accumulation associated with fibrinoid necrosis, producing injury to the basement membrane and resulting in leaky capillaries. Repeated bouts of inflammation and hemorrhage result in the deposition of hemosiderin-laden macrophages. In patients with bland DAH, red blood cells fill the alveoli in the absence of capillary inflammation. Note that there is occasionally some overlap in this classification system; Goodpasture syndrome, collagen vascular disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus may be associated with pulmonary hemorrhage with or without pulmonary capillaritis. For DAH with capillaritis, autoantibodies directed against the alveolar basement membrane produces direct damage or basement membrane injury results from immune complex deposition.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

CT

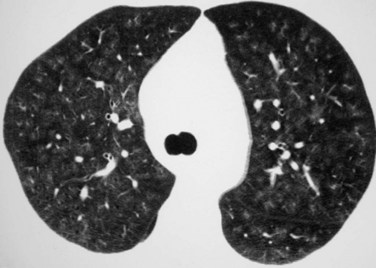

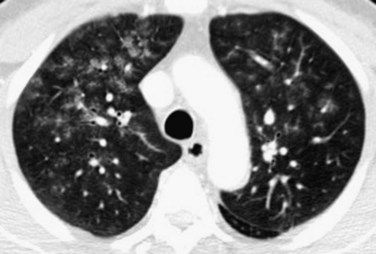

CT and high-resolution CT (HRCT) typically show multifocal or diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacity and consolidation. Ground-glass attenuation poorly defined nodules (Fig. 101-1) may occur. Often, a network pattern of smooth interlobular septal thickening is superimposed in the regions of ground-glass opacity.

VASCULITIS

The histopathologic hallmark of vasculitis is the presence of angiocentric inflammation, usually extending through all layers of blood vessel walls. Fibrinoid necrosis and perivascular fibrosis are also commonly present, and may ultimately lead to vascular obliteration and occlusion. Both leukocytoclastic (neutrophil-predominant) and granulomatous (lymphocyte-predominant) vasculitic patterns may occur. Most pulmonary vasculitides share the common pathogenesis of immune complex deposition in the vessel wall, with activation of complement and cellular chemotaxis, leading to an enzymatic and inflammatory cascade that ultimately produces vascular damage. The whole process may be antigen-driven, which may explain the association of a number of vasculitides with viral infections and collagen vascular disorders. However, some granulomatous vasculitides may be the result of cell-mediated immunity rather than immune complex deposition. A number of vasculitides may affect the thorax, the lung in particular. The main histopathologic derangement of vasculitides affecting the lung is capillaritis, perhaps associated with inflammation of slightly larger vessels (Table 101-2).

| Location | Cause |

|---|---|

| Large vessels (aorta and major branch vessels) | |

| Medium-sized vessels (visceral arteries)*† | |

| Small vessels (arterioles, capillaries, venules, distal intraparenchymal small arteries leading to arterioles) |

* Some overlap in level of involvement may occur, particularly with either large or small vessel vasculitides involving medium-sized vessels.

† Visceral arteries = coronary, hepatic, mesenteric, and renal arteries

WEGENER’S GRANULOMATOSIS

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

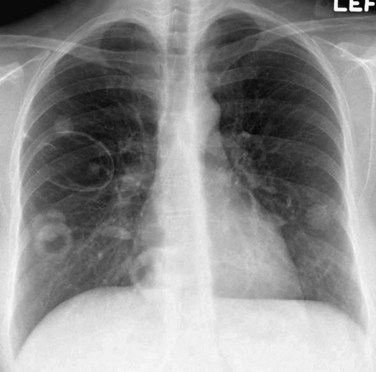

Chest radiographs are abnormal in up to 85% of patients with WG at some point during the course of the illness. The most characteristic imaging manifestation of WG is multiple, usually bilateral, nodules or masses typically measuring 2 to 4 cm, often associated with cavitation (Fig. 101-2). Pulmonary opacities and cavities in patients with WG may occasionally be much larger. WG-related pulmonary cavities often have a rather thick, irregular internal wall, and air-fluid levels are occasionally seen. Ground-glass opacity surrounding the cavities is a frequent finding and is usually caused by adjacent alveolitis or pulmonary hemorrhage.

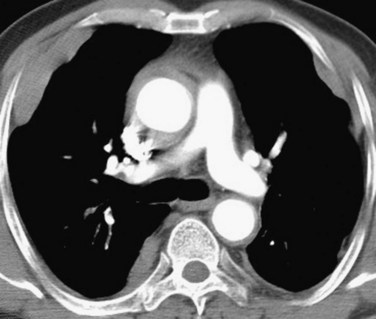

CT

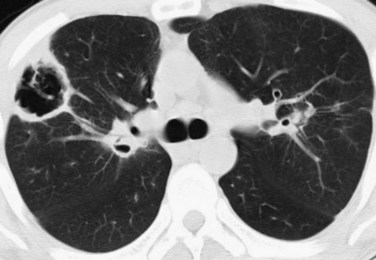

Thoracic CT scanning in patients with WG also typically shows multiple bilateral nodules and/or masses,1 and is far more sensitive for the detection of cavitation than chest radiography. In fact, most nodules measuring more than 2 cm in patients with WG will show cavitation on CT (Fig. 101-3). Nodules and cavities in patients with WG have no particular zonal predilection, and are somewhat randomly distributed throughout the lungs.

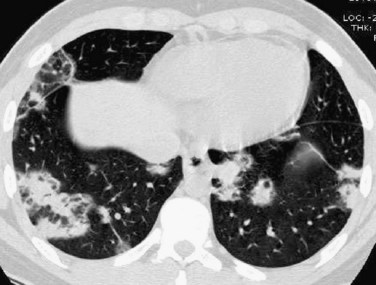

Patchy multifocal or diffuse ground-glass opacities, often with areas of consolidation,1 is the second most common thoracic imaging manifestation of WG, and may occur in the absence of pulmonary nodules. These opacities are usually the result of pulmonary hemorrhage. Occasionally, areas of consolidation may be subpleural or peribronchiolar in distribution, simulating organizing pneumonia; the so-called atoll or reverse halo sign may also be seen (Fig. 101-4).

Tracheobronchial wall thickening and narrowing may be present in patients with WG,1 and may even lead to atelectasis. Typically, airway involvement in patients with WG predominates in the subglottic region and extends a variable distance caudally (Fig. 101-5). The airway wall thickening is circumferential and often nodular and irregular, occasionally resulting in tracheobronchial stenosis. The tracheobronchial thickening may occasionally calcify.

MICROSCOPIC POLYANGIITIS

Microscopic polyangiitis is a small-vessel vasculitis2 that closely resembles polyarteritis nodosa, except that the latter usually involves medium-sized vessels, often involves abdomen viscera, and rarely produces DAH.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

The average age of onset is about 50 years, and men are more commonly affected than women.2 Fever and constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss and malaise, are common in patients with microscopic polyangiitis. Patients also often complain of myalgias and arthralgias, and individually affected organ systems may also produce particular symptoms. For example, involvement of the gastrointestinal tract may produce diarrhea and bleeding, whereas involvement of the skin may produce dermatologic manifestations, such as purpura and splinter hemorrhages. Peripheral neuropathy may occur. Shortness of breath, cough, and hemoptysis are the more common symptoms of thoracic involvement, and hemoptysis may be life-threatening.

BEHÇET SYNDROME

Behçet syndrome is a rare condition characterized by the combination of mucosal aphthous stomatitis, uveitis, genital ulcers, and skin lesions,3 particularly erythema nodosum, and is a systemic multisystem disorder that may also be associated with arthritis, meningoencephalitis, thrombophlebitis, and cutaneous vasculitis.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The cause of Behçet syndrome is unknown. Some have speculated that a virus may be responsible, whereas others have implicated an immunologic mechanism as the cause. Histopathologically, a small-vessel vasculitis is present caused by extensive inflammation of vessel walls with plasma cells and lymphocytes.3 Larger vessel involvement may also occur, resulting in aneurysm formation. Venous thrombosis may also be present.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Males are much more commonly affected than females in patients with Behçet syndrome. The typical age of diagnosis is 20 to 30 years, and Behçet syndrome is most commonly encountered in the Middle East, Mediterranean countries, and Japan.3 Patients usually present with chronic remitting oral and genital ulcers and skin lesions, especially erythema nodosum, as well as uveitis. A number of systemic manifestations are common in Behçet syndrome, including arthritis, neuropathy, thrombophlebitis, and aneurysm formation. Thoracic involvement usually occurs in the setting of established disease, with patients complaining of chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, and hemoptysis. Hemoptysis may be massive and life-threatening and is the cause of death in up to 39% of patients.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

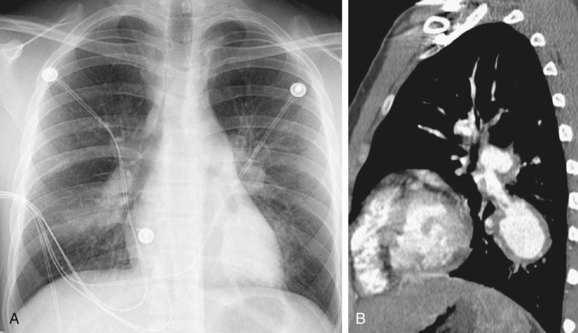

Chest radiographs in patients with Behçet syndrome may show multifocal or diffuse bilateral air space opacities in patients with thoracic symptoms and hemoptysis; these findings are nonspecific and resemble those of other causes of DAH.3 Much more characteristic of Behçet syndrome is the presence of pulmonary artery aneurysms. On chest radiographs, pulmonary artery aneurysms appear as central hilar prominence or perihilar rounded opacity of variable size (Fig. 101-6A).3 Aneurysms may grow rapidly, and therefore a rapid change in the appearance of the hilum may be suggestive of aneurysm development in the proper context. The margins of the aneurysms may be poorly defined because of surrounding pulmonary hemorrhage.

CT

CT is clearly much more sensitive for the detection and characterization of pulmonary artery aneurysms (see Fig. 101-6B), and may even detect thrombosed pulmonary artery aneurysms that would be difficult to detect by catheter pulmonary angiography. Behçet syndrome may closely resemble another condition associated with the development of pulmonary artery aneurysms and venous thrombosis, Hughes-Stovin syndrome.

Thrombotic complications are also common in patients with Behçet syndrome and may involve the great veins of the thorax and the proximal pulmonary arteries.3 Pulmonary arterial thrombosis or emboli, as well as vasculitis, may produce pulmonary infarction, which usually manifests on chest radiographs or CT scans as a subpleural wedge-shaped consolidation.

TAKAYASU ARTERITIS

Takayasu arteritis is an uncommon large-vessel vasculitis that primarily affects the aorta and its branch vessels, including the coronary arteries, and occasionally the pulmonary arteries. Several classification schemes for Takayasu arteritis have been advanced (see later), and criteria for diagnosis have also been established (Table 101-3).

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| Age of disease onset ≤40 yr | Development of signs or symptoms attributable to Takayasu arteritis at age 40 or younger |

| Extremity claudication | Muscular fatigue, pain, discomfort involving one or more of the extremities with exercise, particularly upper extremities |

| Decreased brachial artery pulse | Diminished brachial artery pulse |

| Differential blood pressure | Blood pressure differential between two arms of 10 mm Hg or more |

| Vascular bruits | Bruit detectable on auscultation over subclavian arteries or abdominal aorta |

| Arteriographic abnormalities | Narrowing or occlusion of the aorta, major branch vessels of the aorta, or large vessels of the extremities unrelated to atherosclerosis, fibromuscular dysplasia, or similar process |

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Takayasu arteritis usually occurs in patients younger than 40 years and shows a strong predilection for women, who account for 80% to 90% of cases. The highest disease prevalence has been reported in Asia, especially Japan, although it may be underreported in Europe and North America.4

Etiology and Pathophysiology

An immunologic mechanism is thought to be responsible for Takayasu arteritis. The possibility of a heritable cause or hormonal influences has also been considered.4

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

During the early, inflammatory stage, fever, pain in the region of the inflamed vessels, myalgias, fatigue, and malaise are common. On physical examination, bruits or diminished pulse over the involved vessels may be detected. Ischemic symptoms may result when vascular stenoses or occlusions are present. When the brachiocephalic vessels are involved, neurologic symptoms may dominate the clinical picture.4

In the late occlusive phase, ischemic symptoms are the primary manifesting features, including angina, claudication, syncope, and visual impairment.4

Imaging Techniques and Findings

CT

CT is useful for the early diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis because it allows evaluation of arterial wall thickness rather than just the luminal diameter. This is especially important because early diagnosis and treatment are associated with improved prognosis in patients with Takayasu arteritis. The findings of Takayasu arteritis on CT and CT angiography (CTA) include stenoses, occlusions, aneurysms (Fig. 101-7), and concentric arterial wall thickening affecting the aorta and its branches, as well as the the pulmonary arteries. Occasionally, coronary artery aneurysms may be seen. In late-stage Takayasu arteritis, extensive vascular calcification may occur.4 Limitations of CT include the need for iodinated contrast material and ionizing radiation, which may be particularly important given the typically young age of patients with Takayasu arteritis.

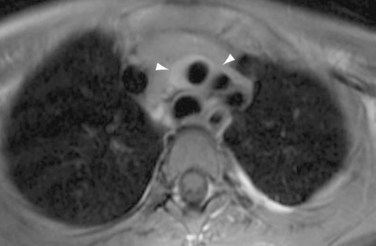

MRI

Findings of Takayasu arteritis on MRI include mural thrombi, signal alterations within and surrounding inflamed vessels (Fig. 101-8), fusiform vascular dilation or frank aneurysm formation, thickened aortic valvular cusps, multifocal stenoses, and concentric thickening of the aortic wall. MRI may also show pericardial effusions and signal abnormalities within the pericardium, representing fluid and granulation tissue.4 The main disadvantages of MRI in patients with Takayasu arteritis include difficulty in visualizing small branch vessels and poor visualization of vascular calcification. MRI is also expensive, and is frequently less available in regions in which Takayasu arteritis is most prevalent.

MR angiography provides detailed vascular information, including the location, degree, and extent of stenoses, as well as the presence of aneurysms. The patency of surgical bypass grafts may also be readily assessed.4

Angiography

Angiography has traditionally been the primary procedure for the diagnostic evaluation of Takayasu arteritis. Angiography often demonstrates long, smooth, tapered stenoses that range from mild to severe (Fig. 101-9). Arterial occlusions may be present, and collateral vessels or the subclavian steal phenomenon may be seen. Angiography is useful for guiding and evaluating interventional procedures, such as angioplasty or stent placement. However, angiography is invasive, may require a large amount of iodinated contrast material, delivers a substantial radiation dose, and can be difficult to perform in patients with long-segment stenoses or heavy arterial calcification. Additionally, angiography does not depict changes in wall architecture as well as cross-sectional techniques, and cannot differentiate between vascular narrowing caused by acute mural inflammation from that caused by chronic transmural fibrosis. Importantly, ischemic complications resulting from angiography in patients with Takayasu arteritis may be substantial, possibly because blood coagulation activity is increased in these patients.

CHURG-STRAUSS SYNDROME

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Churg-Strauss syndrome most commonly affects men with asthma, usually in their late 30s through 50 years of age.5 Multiorgan involvement is common, with the skin, lungs, peripheral nerves, heart, and abdominal viscera potentially affected. Pansinusitis and allergic rhinitis are common as well.

Manifestations of Disease

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

Chest radiographs are commonly abnormal in patients with Churg-Strauss syndrome, usually showing transient, nonsegmental, occasionally subpleural, consolidation.5 No particular zonal predilection has been noted. Occasionally, pulmonary opacities may be nodular in configuration (Fig. 101-10), somewhat resembling Wegener’s granulomatosis but, unlike Wegener’s granulomatosis, cavitation does not usually occur.

Differential Diagnosis

From Clinical Presentation

As with other vasculitides and numerous inflammatory processes, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate is usually elevated. Blood hypereosinophilia is usually present, typically more than 10% of the peripheral white blood cell count. The American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for Churg-Strauss syndrome are presented in Box 101-1. Note that the presence of vasculitis is not among these criteria, because the presence of extravascular tissue eosinophilia is a more sensitive indicator of disease.

GIANT CELL ARTERITIS

Imaging Techniques and Findings

CT

Giant cell arteritis may produce visible thickening and enhancement of the walls of the affected large arteries, usually in a patchy fashion. These findings are best appreciated on unenhanced and enhanced (Fig. 101-11) CT studies. Stenoses and occlusions may occur. Bilateral pleural effusions may be seen, and a reticular and nodular pulmonary parenchymal pattern has been described. A larger nodular pattern has also been reported in patients with giant cell arteritis, but because there is some overlap between the pattern and areas of involvement in giant cell arteritis and other systemic vasculitides, such as Wegener’s granulomatosis and Churg-Strauss syndrome, it is not clear whether pulmonary nodules truly represent a manifestation of giant cell arteritis.

CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASES AND SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

NECROTIZING SARCOID GRANULOMATOSIS

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis is a rare disorder characterized by the following6:

IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY HEMOSIDEROSIS

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

IPH usually affects children and, much less commonly, young adults; children younger than 10 years are most commonly affected. Males are more commonly affected than females, at least with adult-onset disease. Patients with IPH characteristically present with hemoptysis. Other nonspecific symptoms, such as fever, cough, chest pain, shortness of breath, and iron deficiency anemia, may be present.7 Hemoptysis is not invariably seen. In some cases, the onset of disease is insidious, whereas in others, disease onset is acute. Some patients develop lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly.7 Later in the course of disease, with repeated episodes of hemorrhage, pulmonary fibrosis may develop, associated with other signs and symptoms, such as digital clubbing and progressive dyspnea or decreased exercise tolerance.

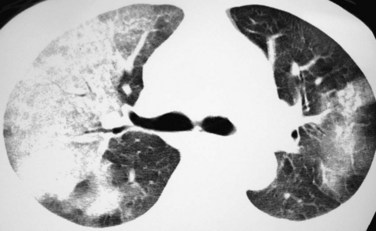

Imaging Techniques and Findings

CT

CT and HRCT in patients with IPH show findings typical of pulmonary hemorrhage—multifocal, bilateral, patchy or diffuse ground-glass opacities, with or without areas of air space consolidation associated with smooth interlobular septal thickening (Fig. 101-12). Findings tend to favor the dependent regions of the lung. Poorly defined ground-glass centrilobular nodules may be seen.

GOODPASTURE SYNDROME

Imaging Techniques and Findings

CT

CT and HRCT in patients with Goodpasture syndrome show findings typical of pulmonary hemorrhage—multifocal, bilateral, patchy or diffuse ground-glass opacities (Fig. 101-13), with or without areas of air space consolidation associated with smooth interlobular septal thickening. Findings tend to favor the dependent regions of lung. Poorly defined ground-glass centrilobular nodules are common.

Chae EJ, Do KH, Seo JB, et al. Radiologic and clinical findings of Behçet disease: comprehensive review of multisystemic involvement. Radiographics. 2008;28:e31.

Gotway MB, Araoz PA, Macedo TA, et al. Imaging findings in Takayasu’s arteritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1945-1950.

Hiller N, Lieberman S, Chajek-Shaul T, et al. Thoracic manifestations of Behçet disease at CT. Radiographics. 2004;24:801-808.

Schwarz MI, Brown KK. Small vessel vasculitis of the lung. Thorax. 2000;55:502-510.

Semple D, Keogh J, Forni L, Venn R. Clinical review: vasculitis on the intensive care unit—part 1: diagnosis. Crit Care. 2005;9:92-97.

1 Lee KS, Kim TS, Fujimoto K, et al. Thoracic manifestation of Wegener’s granulomatosis: CT findings in 30 patients. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:43-51.

2 Collins CE, Quismorio FPJr. Pulmonary involvement in microscopic polyangiitis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:447-451.

3 Hiller N, Lieberman S, Chajek-Shaul T, et al. Thoracic manifestations of Behçet disease at CT. Radiographics. 2004;24:801-808.

4 Gotway MB, Araoz PA, Macedo TA, et al. Imaging findings in Takayasu’s arteritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1945-1950.

5 Kim YK, Lee KS, Chung MP, et al. Pulmonary involvement in Churg-Strauss syndrome: an analysis of CT, clinical, and pathologic findings. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:3157-3165.

6 Lazzarini LC, de Fatima do Amparo Teixeira M, Souza Rodrigues R, Marcos Nunes Valiante P. Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis in a family of patients with sarcoidosis reinforces the association between both entities. Respiration. 2008;76:356-360.

7 Susarla SC, Fan LL. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndromes in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:314-320.

FIGURE 101-1

FIGURE 101-1

FIGURE 101-2

FIGURE 101-2

FIGURE 101-3

FIGURE 101-3

FIGURE 101-4

FIGURE 101-4

FIGURE 101-5

FIGURE 101-5

FIGURE 101-6

FIGURE 101-6

FIGURE 101-7

FIGURE 101-7

FIGURE 101-8

FIGURE 101-8

FIGURE 101-9

FIGURE 101-9

FIGURE 101-10

FIGURE 101-10

FIGURE 101-11

FIGURE 101-11

FIGURE 101-12

FIGURE 101-12

FIGURE 101-13

FIGURE 101-13