1.2 Pulmonary gas exchange

The basics

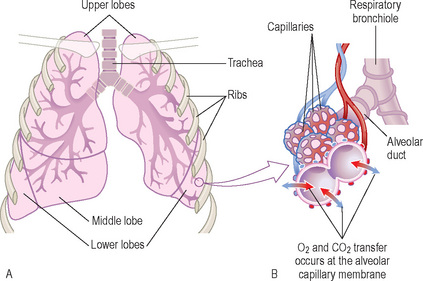

The exchange takes place between tiny air sacs called alveoli and blood vessels called capillaries. Because they each have extremely thin walls and come into very close contact (the alveolar–capillary membrane), CO2 and O2 are able to move (diffuse) between them (Figure 1).

Pulmonary gas exchange: partial pressures

Note

Carbon dioxide elimination

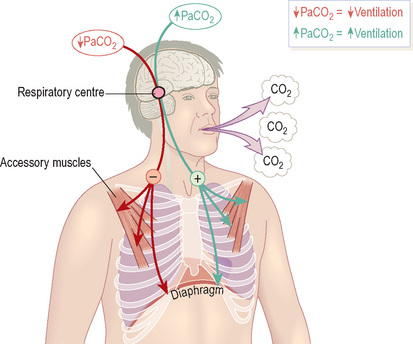

Ventilation is regulated by an area in the brainstem called the respiratory centre. This area contains specialised receptors that sense the PaCO2 and connect with the muscles involved in breathing. If it is abnormal, the respiratory centre adjusts the rate and depth of breathing accordingly (Figure 2).

Key point

PaCO2is controlled by ventilation and the level of ventilation is adjusted to maintain PaCO2within tight limits.

In patients who rely on hypoxic drive, overzealous correction of hypoxaemia, with supplemental O2, may depress ventilation, leading to a catastrophic rise in PaCO2. Patients with chronic hypercapnia must therefore be given supplemental O2 in a controlled fashion with careful ABG monitoring. The same does not apply to patients with acute hypercapnia.

Haemoglobin oxygen saturation (SO2)

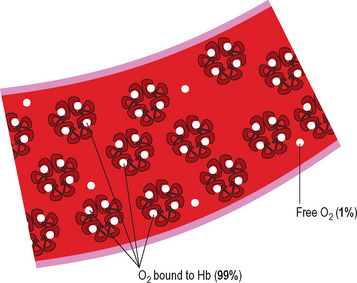

In fact, almost all O2 molecules in blood are bound to a protein called haemoglobin Hb (Figure 3). Because of this, the amount of O2 in blood depends on two factors:

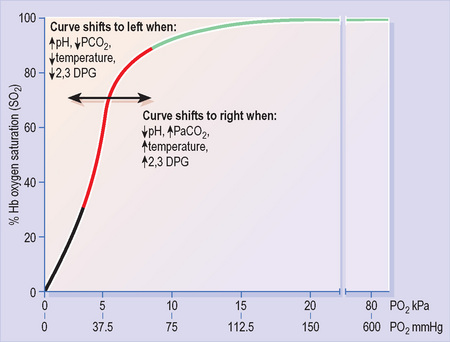

Oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve

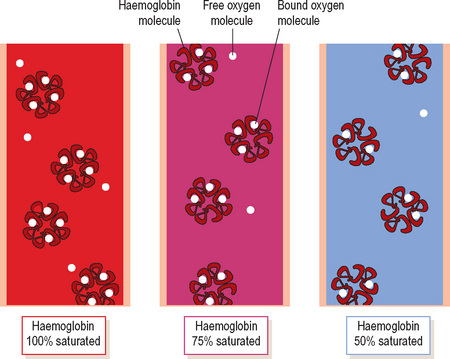

PO2 can be thought of as the driving force for O2 molecules to bind to Hb: as such it regulates the SO2. The oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve (Figure 5) shows the SO2 that will result from any given PO2.

Alveolar ventilation and PaO2

We have now seen how PaO2 regulates the SaO2. But what determines PaO2?

There are three major factors that dictate the PaO2:

Alveolar ventilation

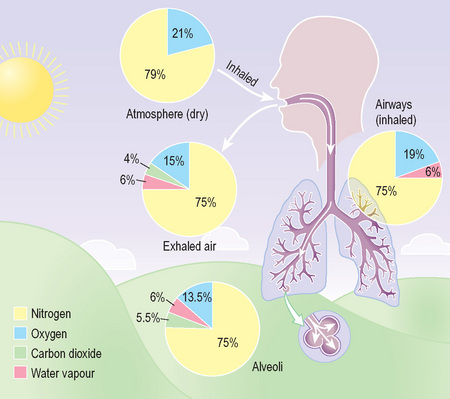

Unlike air in the atmosphere, alveolar air contains significant amounts of CO2 (Figure 6). More CO2 means a lower PO2 (remember the partial pressure of a gas reflects its share of the total volume).

Whereas hyperventiation can increase alveolar PO2 only slightly (bringing it closer to the PO2 of inspired air), there is no limit to how far alveolar PO2 (and hence PaO2) can fall with inadequate ventilation.

Key point

Both oxygenation and CO2 elimination depend on alveolar ventilation: impaired ventilation causes PaO2to fall and PaCO2to rise.

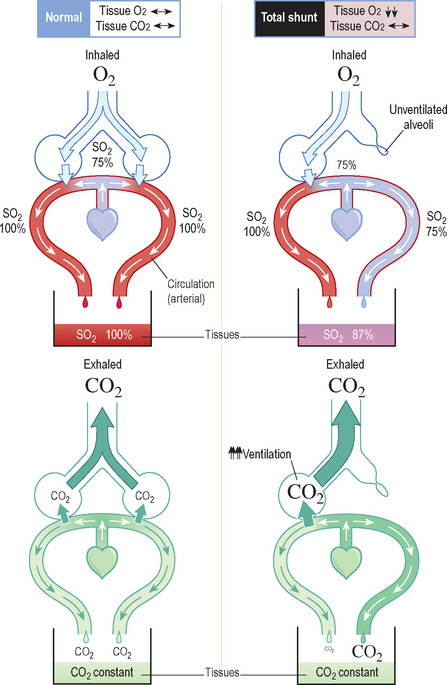

Ventilation/perfusion mismatch and shunting

Imagine if alveoli in one area of lung are poorly ventilated (e.g. due to collapse or consolidation). Blood passing these alveoli returns to the arterial circulation with less O2 and more CO2 than normal. This is known as shunting1.

Key point

Provided overall alveolar ventilation is maintained, V/Q mismatch does not lead to an increase in PaCO2.

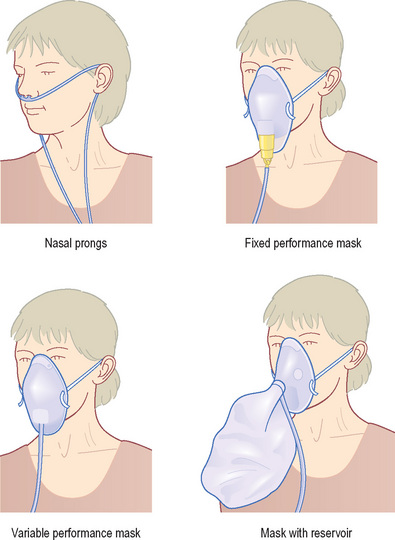

FiO2 and oxygenation

A low PaO2 may result from either V/Q mismatch or inadequate ventilation and, in both cases, increasing the FiO2 will improve the PaO2. The exact FiO2 requirement varies depending on how severely oxygenation is impaired and will help to determine the choice of delivery device (Figure 8). When the cause is inadequate ventilation it must be remembered that increasing FiO2 will not reverse the rise in PaCO2.