Chapter 10 Pulmonary emboli and venous thromboses

PULMONARY EMBOLI

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a diagnosis to be made in the emergency department. If diagnosed and treated appropriately, the mortality is of the order of 8–10%, with most patients dying of comorbidity. If the diagnosis is not made initially, the mortality rises to about one-third of cases1 and patients have a three-fold higher rate of in-hospital adverse events.2

Risk factors

Note: Only 6% of patients with PE have no recognised coexistent illness or risk factor.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The diagnosis is often difficult and approaches to diagnosis remain in a state of flux. Classical signs and symptoms occur only occasionally, and most are non-specific. Clinical judgment enhances the ability of investigations to predict PE, and is now used in most PE investigation algorithms, in association with calculation of pre-test probability (PTP) of PE based on symptoms, signs and risk factors.4

Pre-test probability (PTP)2

| Signs of DVT | 3 |

| PE most likely cause | 3 |

| Active cancer | 1.5 |

| Recent immobilisation (bed rest of 3 days or more, leg plaster for 2 weeks or more, surgery within 3 weeks) | 1.5 |

| Tachycardia (PR > 100/min) | 1 |

| History of haemoptysis | 1 |

PTP is considered high if over 6, intermediate for a score of 3–6, and low for a score of 2 or less.

PE rule-out criteria (PERC)

A gestalt suspicion of low probability of PE together with a refinement of Wells criteria4 has been developed and trialled to exclude PE in outpatient populations.5,6 These PE rule-out criteria (PERC) are: age < 50 years, pulse < 100/min, SaO2 ≥ 95%, no haemoptysis, no oestrogen use, no surgery/trauma requiring hospitalisation within 4 weeks, no prior venous thromboembolism (VTE) and no unilateral leg swelling.

In a large multicentre study, the combination of low suspicion and negative PERC reduced the probability of VTE to below 2% in those with low suspicion of PE.6

Investigations

The Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis (PIOPED) study found that, although an abnormal (low, intermediate or high probability) ventilation/perfusion lung scan was very sensitive (98%) for PE, it was not nearly as specific (10%) as previously thought, and only a minority of patients with PE had high probability scans.7 Ultrasonography of leg veins (to look for deep vein thrombosis (DVT)) and pulmonary angiography should be used much more liberally when there is strong clinical suspicion of PE.

Troponin I

Several studies have suggested the use of troponin I in PE to predict the occurrence of complications. Elevated troponin I appears to reliably predict haemodynamic instability and complicated clinical course.8–10 Others have suggested B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) may be a better predictor.11

CT pulmonary angiography

CTPA is useful in the setting of patients with abnormal CXRs. It is more sensitive for central than peripheral PEs and has the advantage of detecting other pulmonary pathology if present. Many authorities are now arguing that CTPA may be used as the single diagnostic test in the emergency department after risk stratification and d-dimer testing.12–14 However, small subsegmental emboli may be missed. The rate of subsequent venous thromboembolism after negative results on CTPA, however, appears to be similar to that seen after negative results on pulmonary angiography.15 So it appears safe to withhold anticoagulation after negative CTPA results. MRI is available in a few centres.

Pulmonary angiography

Nearly 100% specific and sensitive, pulmonary angiography is the ‘gold standard’. A negative study essentially excludes the diagnosis of PE. However, morbidity is 1–4% and mortality is 0.1–0.4%.1 It is not often used, but should be when clinical suspicion is very high but other investigations are normal.

Management

Treatment may need to begin on suspicion, particularly if definitive investigations are unavailable out of hours. Conventional anticoagulation with heparin in currently recommended dose regimens (e.g. 5000 units IV stat followed by 800–1600 units/hour by continuous infusion) is still standard therapy in most centres, although low molecular weight heparins now appear to be at least as effective.16 For haemodynamically compromised patients or those with right ventricular dysfunction, thrombolysis should be considered, although evidence of effectiveness is still limited.

Comments

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM

Diagnostic approach

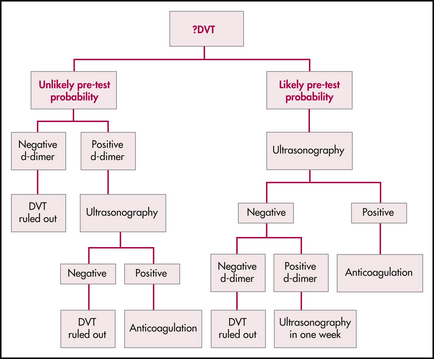

Decision-making is based on an assessment of pre-test probability, d-dimer testing and some form of medical imaging. The following algorithm summarises one approach to the investigation of the patient with a possible DVT based on evidence presently available in the literature.

Determine the patient’s pre-test probability

Clinical ‘impression’ alone is not sufficient. Wells and colleagues17 developed and validated a set of clinical criteria incorporating signs, symptoms, risk factors and alternative diagnoses for stratifying a patient’s pre-test probability of DVT into low, moderate or high risk. In their original study, the approximate rates of DVT for these patient populations were as high as 5%, 33% and 85%, respectively. Some authors have argued that the criteria specifically exclude patients with a history of DVT, and are therefore applicable to first-time presentations only, thus limiting their usefulness. However, further research has included such patients and an updated stratification tool now divides patients into ‘likely’ or ‘unlikely’ risk categories, as shown in Table 10.1. However, a notable exclusion is the pregnant patient.

Table 10.1 Clinical model for predicting the pre-test probability of deep-vein thrombosis∗

| Clinical characteristic | Score |

|---|---|

| Active cancer (patient receiving treatment for cancer within the previous 6 months or currently receiving palliative treatment) | 1 |

| Paralysis, paresis or recent plaster immobilisation of the lower extremities | 1 |

| Recently bedridden for 3 days or more, or major surgery within the previous 12 weeks requiring general or regional anaesthesia | 1 |

| Localised tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system | 1 |

| Entire leg swollen | 1 |

| Calf swelling at least 3 cm larger than that on the asymptomatic side (measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity) | 1 |

| Pitting oedema confined to the symptomatic leg | 1 |

| Collateral superficial veins (nonvaricose) | 1 |

| Previously documented deep vein thrombosis | 1 |

| Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as deep vein thrombosis | –2 |

∗ A score of 2 or higher indicates that the probability of deep vein thrombosis is likely; a score of less than 2 indicates that the probability of deep vein thrombosis is unlikely. In patients with symptoms in both legs, the more symptomatic leg is used.

Reproduced from Wells et al, N Engl J Med 2003; 349:1227–1235, with permission

Determine the d-dimer level

D-dimer is a degradation product from cross-linked fibrin. It rises acutely in the presence of venous thrombosis—and unfortunately it rises in many other conditions as well (advanced age, malignancy, infection, trauma, haemorrhage and even recent major surgery). Numerous assays are currently available—a highly sensitive assay is important.

Medical imaging

If the ultrasound is positive for DVT at any stage of the algorithm, treat the patient. In the ‘unlikely’ patient with a positive d-dimer, if the ultrasound is negative then the likelihood of DVT is exceedingly small and treatment can be withheld. However, in the ‘likely’ patient with a positive d-dimer and a negative ultrasound, the evidence would support repeat ultrasonography at 1 week.

Treatment

Above-knee DVT

A suitable treatment plan for an above-knee DVT is as follows:

Below-knee DVT

Further investigations

Investigations ordered as part of a procoagulant screen include:

(Note: The use of low-molecular-weight heparin interferes with antithrombin III testing.)

1 Dunmire S.M. Pulmonary embolism. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 1989;7:339-354.

2 Kline J.A., Hernandez-Nino J., Jones A.E., et al. Prospective study of the clinical features and outcomes of emergency department patients with delayed diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:592-598.

3 Urokinase-streptokinase embolism trial. Phase II results. JAMA. 1974;229:1606-1613.

4 Wells P.S., Ginsberg J.S., Anderson D.R., et al. Use of a clinical model for safe management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:997-1005.

5 Wolf S.J., McCubbin T.R., Nordenholz K.E., et al. Assessment of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria rule for evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:181-185.

6 Kline J.A., Courtney D.M., Kabrhel C., et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:772-780.

7 The PIOPED investigators. Value of the ventilation/perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. Results of the prospective investigation of pulmonary embolism diagnosis (PIOPED). JAMA. 1990;263:2753-2759.

8 Aksay E., Yanturali S., Kiyan S. Can elevated troponin I levels predict complicated clinical course and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism? Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:138-143.

9 Palmieri V., Gallotta G., Rendina D., et al. Troponin I and right ventricular dysfunction for risk assessment in patients with nonmassive pulmonary embolism in the Emergency Department in combination with clinically based risk score. Intern Emerg Med. 2008;3(2):131-138.

10 Gallotta G., Palmieri V., Piedimonte V., et al. Increased troponin I predicts in-hospital occurrence of hemodynamic instability in patients with sub-massive or non-massive pulmonary embolism independent to clinical, echocardiographic and laboratory information. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:351-357.

11 Maziere F., Birolleau S., Medimagh S., et al. Comparison of troponin I and N-terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide for risk stratification in patients with pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14:207-211.

12 Tilli P., Testa A., Covino M., et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to acute pulmonary embolism in an emergency department. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2006;10:91-98.

13 Mountain D. Multislice computed tomographic pulmonary angiography for diagnosing pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: has the ‘one-stop shop’ arrived? Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18:444-450.

14 Emet M., Ozucelik D.N., Sahin M., et al. Computed tomography pulmonary angiography in the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Adv Ther. 2007;24:1173-1180.

15 Moores L.K., Jackson W.L.Jr., Shorr A.F., et al. Meta-analysis: outcomes in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism managed with computed tomographic pulmonary angiography. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:866-874.

16 Quinlan D.J., McQuillan A., Eikelboom J.W. Low-molecular-weight heparin compared with intravenous unfractionated heparin for treatment of pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:175-183.

17 Wells P., Anderson D. Diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis in the year 2000. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2000;6(4):309-313.

Bates S., Kearon C., Crowther M., et al. A diagnostic strategy involving a quantitative latex D-dimer assay reliably excludes deep venous thrombosis. Ann Int Med. 2003;138(10):787-794.

Cornuz J., Ghali W., Hayoz D. Clinical prediction of deep venous thrombosis using two risk assessment methods in combination with rapid quantitative D-dimer testing. Am J Med. 2002;112(3):198-203.

Forster A., Wells P. The rationale and evidence for the treatment of lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis with thrombolytic agents. Current Opinion in Haematology. 2002;9(5):437-442.

Hyers T. Management of venous thromboembolism: past, present, and future. Arch Int Med. 2003;163(7):759-768.

Kelly J., Hunt B. Role of D-dimers in diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Lancet. 2002;359:456-458.

Kraaijenhagen R., Piovella F., Bernardi E., et al. Simplification of the diagnostic management of suspected deep vein thrombosis. Arch Int Med. 2002;162:907-911.

Minichiello T., Fogarty P. Diagnosis and management of venous thromboembolism. Med Clin N Am. 2008;92:443-465.

Trujillo-Santos J., Herrera S., Page M.A., et al. Predicting adverse outcome in outpatients with acute deep vein thrombosis: findings from the RIETE registry. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(4):789-793.

Wells P., Anderson D. Diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis in the year 2000. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2000;6(4):309-313.

Wells P., Anderson D., et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep vein thrombosis N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1227-1235.