Figure 11-1 illustrates the location of various pulmonary and cardiac structures seen on a CXR (PA view). The following is a short guide to reading a CXR.

Figure 11-1 illustrates the location of various pulmonary and cardiac structures seen on a CXR (PA view). The following is a short guide to reading a CXR.2. Calcifications on Chest X-Ray

Lung neoplasm (primary or metastatic)

Lung neoplasm (primary or metastatic) Silicosis

Silicosis Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis Disseminated varicella infection

Disseminated varicella infection Mitral stenosis (end-stage)

Mitral stenosis (end-stage) Secondary hyperparathyroidism

Secondary hyperparathyroidism3. Cardiac Enlargement

Cardiac Chamber Enlargement

Chronic volume overload

Chronic volume overload Mitral or aortic regurgitation

Mitral or aortic regurgitation Left-to-right shunt (PDA, VSD, AV fistula)

Left-to-right shunt (PDA, VSD, AV fistula) Cardiomyopathy

Cardiomyopathy Ischemic

Ischemic Nonischemic

Nonischemic Decompensated pressure overload

Decompensated pressure overload AS

AS HTN

HTN High-output states

High-output states Severe anemia

Severe anemia Thyrotoxicosis

Thyrotoxicosis Bradycardia

Bradycardia Severe sinus bradycardia

Severe sinus bradycardia

FIGURE 11-1 Normal anatomy on the female chest radiograph in the upright posteroanterior projection (A) and in the lateral projection (B). (From Mettler FA: Primary Care Radiology. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2000.)

Left Atrium

LV failure of any cause

LV failure of any cause Mitral valve disease

Mitral valve disease Myxoma

MyxomaRight Ventricle

Chronic LV failure of any cause

Chronic LV failure of any cause Chronic volume overload

Chronic volume overload Tricuspid or pulmonic regurgitation

Tricuspid or pulmonic regurgitation Left-to-right shunt (ASD)

Left-to-right shunt (ASD) Decompensated pressure overload

Decompensated pressure overload Pulmonic stenosis

Pulmonic stenosis Pulmonary HTN

Pulmonary HTN Primary

Primary Secondary (PE, COPD)

Secondary (PE, COPD) Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease

Pulmonary veno-occlusive diseaseRight Atrium

Multichamber Enlargement

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Acromegaly

Acromegaly Severe obesity

Severe obesityPericardial Disease

Pericardial effusion w/ or w/o tamponade

Pericardial effusion w/ or w/o tamponade Effusive constrictive disease

Effusive constrictive disease Pericardial cyst, loculated effusion

Pericardial cyst, loculated effusionPseudocardiomegaly

Epicardial fat

Epicardial fat Chest wall deformity (pectus excavatum, straight back syndrome)

Chest wall deformity (pectus excavatum, straight back syndrome) Low lung volumes

Low lung volumes AP CXR

AP CXR4. Cavitary Lesion on Chest X-Ray

Necrotizing Infections

Bacteria: anaerobes, Staphylococcus aureus, enteric gram(−) bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Legionella species, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Rhodococcus, Actinomyces

Bacteria: anaerobes, Staphylococcus aureus, enteric gram(−) bacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Legionella species, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Rhodococcus, Actinomyces Mycobacteria: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare

Mycobacteria: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare Bacteria-like: Nocardia species

Bacteria-like: Nocardia species Fungi: Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces hominis, Aspergillus species, Mucor species

Fungi: Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces hominis, Aspergillus species, Mucor species Parasitic: Entamoeba histolytica, Echinococcus, Paragonimus westermani

Parasitic: Entamoeba histolytica, Echinococcus, Paragonimus westermaniCavitary Infarction

Bland infarction (w/ or w/o superimposed infection)

Bland infarction (w/ or w/o superimposed infection) Lung contusion

Lung contusionSeptic Embolism

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus Anaerobes

Anaerobes Others

OthersVasculitis

Wegener’s granulomatosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis Periarteritis

PeriarteritisNeoplasms

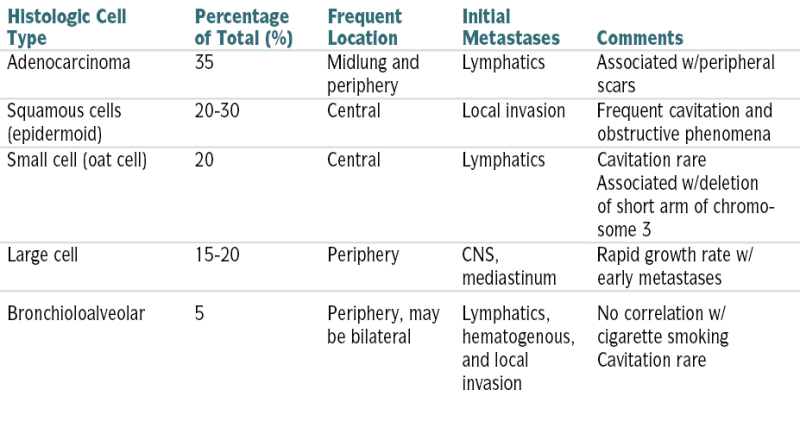

Bronchogenic carcinoma

Bronchogenic carcinoma Metastatic carcinoma

Metastatic carcinoma Lymphoma

LymphomaMiscellaneous Lesions

Cysts, blebs, bullae, or pneumatocele w/ or w/o fluid collections

Cysts, blebs, bullae, or pneumatocele w/ or w/o fluid collections Sequestration

Sequestration Empyema w/air-fluid level

Empyema w/air-fluid level Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis5. Mediastinal Masses or Widening on Chest X-Ray

Lymphoma: Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Lymphoma: Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis Vascular: aortic aneurysm, ectasia or tortuosity of aorta or bronchocephalic vessels

Vascular: aortic aneurysm, ectasia or tortuosity of aorta or bronchocephalic vessels Carcinoma: lungs, esophagus

Carcinoma: lungs, esophagus Esophageal diverticula

Esophageal diverticula Hiatal hernia

Hiatal hernia Achalasia

Achalasia Prominent pulmonary outflow tract: pulmonary HTN, PE, right-to-left shunts

Prominent pulmonary outflow tract: pulmonary HTN, PE, right-to-left shunts Trauma: mediastinal hemorrhage

Trauma: mediastinal hemorrhage Pneumomediastinum

Pneumomediastinum Lymphadenopathy caused by silicosis and other pneumoconioses

Lymphadenopathy caused by silicosis and other pneumoconioses Leukemias

Leukemias Infections: TB, viral (rare), mycoplasmal (rare), fungal, tularemia

Infections: TB, viral (rare), mycoplasmal (rare), fungal, tularemia Thymoma

Thymoma Teratoma

Teratoma Bronchogenic cyst

Bronchogenic cyst Pericardial cyst

Pericardial cyst Neurofibroma, neurosarcoma, ganglioneuroma

Neurofibroma, neurosarcoma, ganglioneuromaB. Use and Interpretation of Pulmonary Function Tests

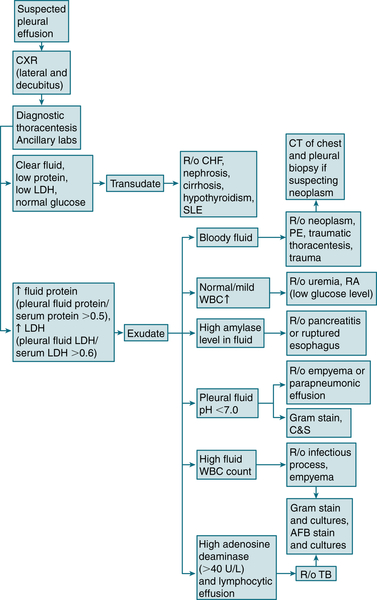

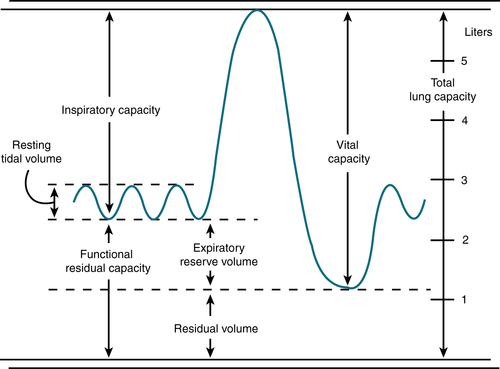

Basic spirometry: Figure 11-2

Basic spirometry: Figure 11-2 PFTs in common lung diseases: Table 11-1

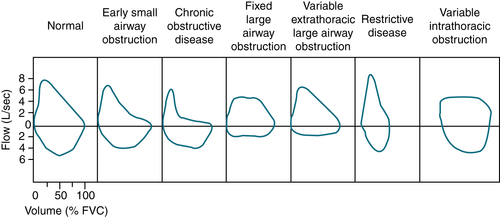

PFTs in common lung diseases: Table 11-1 Flow volume curves: Figure 11-3

Flow volume curves: Figure 11-3

FIGURE 11-2 Basic spirometry. Long volumes obtained with a bell spirometer. (From Kiss GT: Diagnosis and Management of Pulmonary Disease in Primary Practice. Menlo Park, Calif, Addison-Wesley, 1982.)

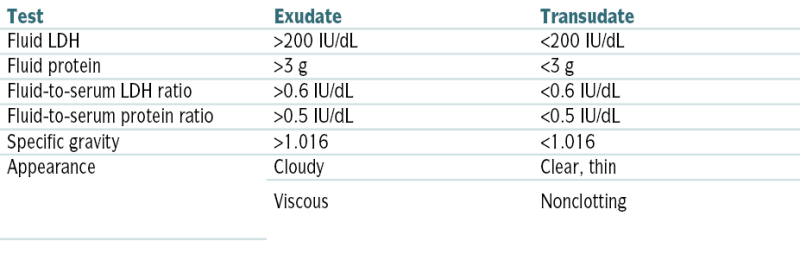

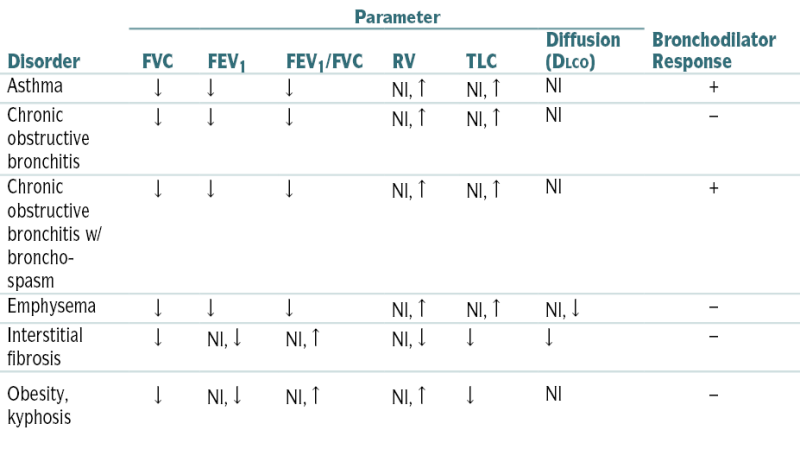

TABLE 11-1

Pulmonary Function Test Patterns in Common Lung Diseases

| Disorder | Parameter | Bronchodilator Response | |||||

| FVC | FEV1 | FEV1/FVC | RV | TLC | Diffusion (DLCO) | ||

| Asthma | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | Nl, ↑ | Nl, ↑ | Nl | + |

| Chronic obstructive bronchitis | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | Nl, ↑ | Nl, ↑ | Nl | − |

| Chronic obstructive bronchitis w/ bronchospasm | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | Nl, ↑ | Nl, ↑ | Nl | + |

| Emphysema | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | Nl, ↑ | Nl, ↑ | Nl, ↓ | − |

| Interstitial fibrosis | ↓ | Nl, ↓ | Nl, ↑ | Nl, ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | − |

| Obesity, kyphosis | ↓ | Nl, ↓ | Nl, ↑ | Nl, ↑ | ↓ | Nl | − |

↑, greater than predicted; ↓, less than predicted.

FIGURE 11-3 Flow-volume curves of restrictive disease and various types of obstructive diseases compared with normal curves.

C. Pulmonary Formulas

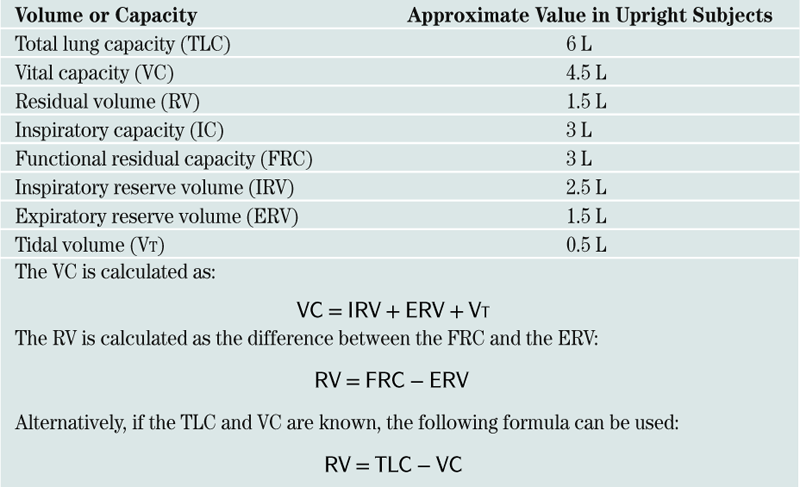

Lung volumes: Box 11-1

Lung volumes: Box 11-1 Alveolar-arterial O2 gradient (A-a gradient): Box 11-2

Alveolar-arterial O2 gradient (A-a gradient): Box 11-2 Evaluation of pt in respiratory failure: Box 11-3

Evaluation of pt in respiratory failure: Box 11-3D. Mechanical Ventilation

Indications (Please see section “M” for Respiratory Failure Classification)

E >10 L/min

E >10 L/minICU Sedation

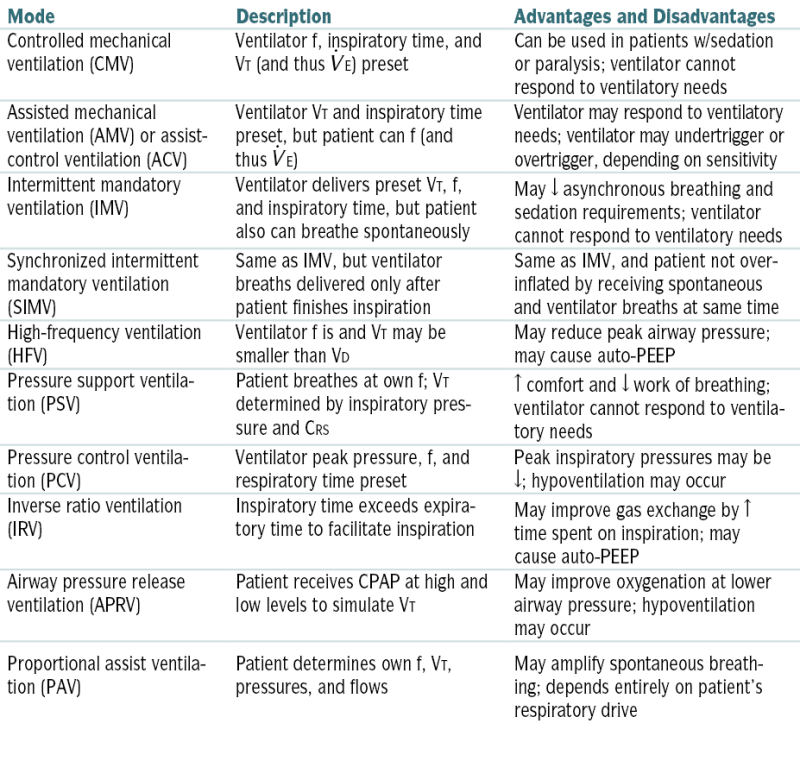

Common Modes of Mechanical Ventilation

TABLE 11-2

Modes of Positive-Pressure Ventilation

| Mode | Description | Advantages and Disadvantages |

| Controlled mechanical ventilation (CMV) | Ventilator f, inspiratory time, and VT (and thus  E) preset E) preset |

Can be used in patients w/sedation or paralysis; ventilator cannot respond to ventilatory needs |

| Assisted mechanical ventilation (AMV) or assist-control ventilation (ACV) | Ventilator VT and inspiratory time preset, but patient can f (and thus  E) E) |

Ventilator may respond to ventilatory needs; ventilator may undertrigger or overtrigger, depending on sensitivity |

| Intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV) | Ventilator delivers preset VT, f, and inspiratory time, but patient also can breathe spontaneously | May ↓ asynchronous breathing and sedation requirements; ventilator cannot respond to ventilatory needs |

| Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) | Same as IMV, but ventilator breaths delivered only after patient finishes inspiration | Same as IMV, and patient not overinflated by receiving spontaneous and ventilator breaths at same time |

| High-frequency ventilation (HFV) | Ventilator f is and VT may be smaller than VD | May reduce peak airway pressure; may cause auto-PEEP |

| Pressure support ventilation (PSV) | Patient breathes at own f; VT determined by inspiratory pressure and CRS | ↑ comfort and ↓ work of breathing; ventilator cannot respond to ventilatory needs |

| Pressure control ventilation (PCV) | Ventilator peak pressure, f, and respiratory time preset | Peak inspiratory pressures may be ↓; hypoventilation may occur |

| Inverse ratio ventilation (IRV) | Inspiratory time exceeds expiratory time to facilitate inspiration | May improve gas exchange by ↑ time spent on inspiration; may cause auto-PEEP |

| Airway pressure release ventilation (APRV) | Patient receives CPAP at high and low levels to simulate VT | May improve oxygenation at lower airway pressure; hypoventilation may occur |

| Proportional assist ventilation (PAV) | Patient determines own f, VT, pressures, and flows | May amplify spontaneous breathing; depends entirely on patient’s respiratory drive |

CRS, Respiratory system compliance; f, respiratory rate; VD, dead space.

Modified from Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds): Goldman’s Cecil Medicine, 22nd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2004.

Selection of Ventilator Settings

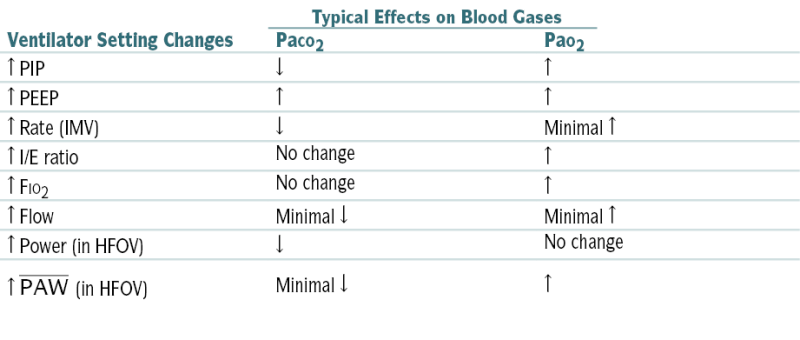

TABLE 11-3

Effects of Ventilator Setting Changes

| Typical Effects on Blood Gases | ||

| Ventilator Setting Changes | PaCO2 | PaO2 |

| ↑ PIP | ↓ | ↑ |

| ↑ PEEP | ↑ | ↑ |

| ↑ Rate (IMV) | ↓ | Minimal ↑ |

| ↑ I/E ratio | No change | ↑ |

| ↑ FIO2 | No change | ↑ |

| ↑ Flow | Minimal ↓ | Minimal ↑ |

| ↑ Power (in HFOV) | ↓ | No change |

↑  (in HFOV) (in HFOV) |

Minimal ↓ | ↑ |

HFOV, High-frequency oscillatory ventilation; I/E, inspiratory/expiratory ratio;  , mean airway pressure; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure.

, mean airway pressure; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure.

From Tschudy MM, Arcara KM: The Harriet Lane Handbook, 19th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2012.

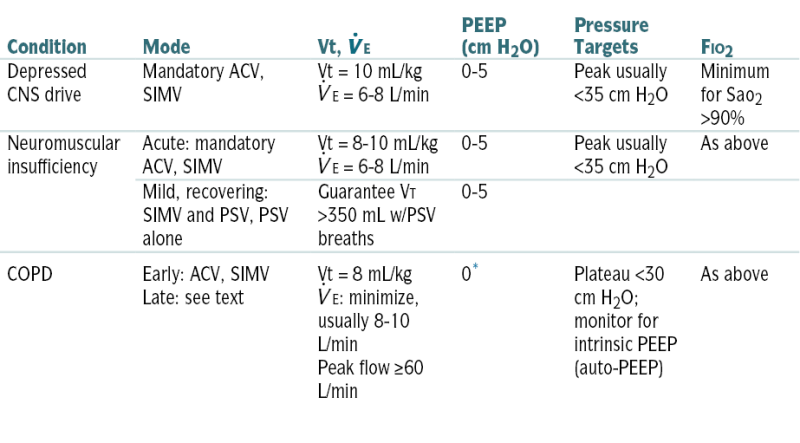

TABLE 11-4

Common Ventilator Machine Settings for Various Disorders

| Condition | Mode | Vt,  E E |

PEEP (cm H2O) | Pressure Targets | FIO2 |

| Depressed CNS drive | Mandatory ACV, SIMV | Vt = 10 mL/kg E = 6-8 L/min E = 6-8 L/min |

0-5 | Peak usually <35 cm H2O | Minimum for Sao2 >90% |

| Neuromuscular insufficiency | Acute: mandatory ACV, SIMV | Vt = 8-10 mL/kg E = 6-8 L/min E = 6-8 L/min |

0-5 | Peak usually <35 cm H2O | As above |

| Mild, recovering: SIMV and PSV, PSV alone | Guarantee VT >350 mL w/PSV breaths | 0-5 | |||

| COPD | Early: ACV, SIMV Late: see text |

Vt = 8 mL/kg E: minimize, usually 8-10 L/min E: minimize, usually 8-10 L/minPeak flow ≥60 L/min |

0∗ | Plateau <30 cm H2O; monitor for intrinsic PEEP (auto-PEEP) | As above |

∗ PEEP added to obstructive disease only in special circumstances.

From Noble J (ed): Textbook of Primary Care Medicine, 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mosby, 1996.

E (VT time rate) to nlize the pH and the PaCO2.

E (VT time rate) to nlize the pH and the PaCO2.Major Complications

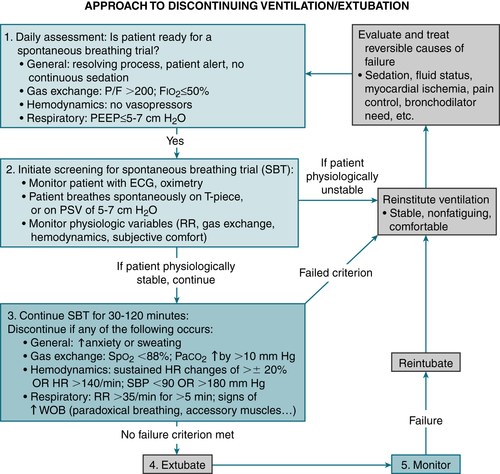

Withdrawal of Mechanical Ventilatory Support

Common Criteria for Ventilator Weaning

E <10 L/min, w/ability to double the resting

E <10 L/min, w/ability to double the resting  E

E

FIGURE 11-4 Algorithm for assessing whether a patient is ready to be liberated from mechanical ventilation and extubated. P/F, PaO2/FIO2 ratio; WOB, work of breathing. (From Goldman L, Schafer AI [eds]: Goldman’s Cecil Medicine, 24th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2012.)

Methods of Weaning

Failure to Wean from Mechanical Ventilator

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

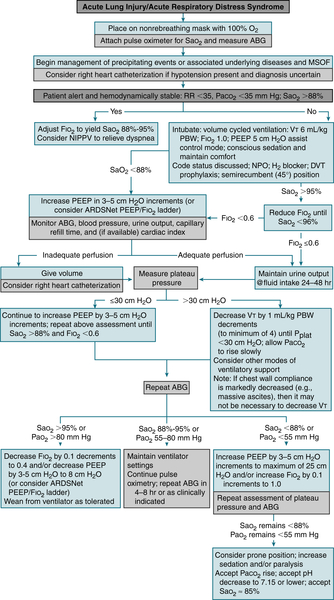

E. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

Etiology

Sepsis (>40%)

Sepsis (>40%) Aspiration: near-drowning, aspiration of gastric contents (>30%)

Aspiration: near-drowning, aspiration of gastric contents (>30%) Trauma (>20%)

Trauma (>20%) Multiple transfusions, blood products

Multiple transfusions, blood products Drugs (OD of morphine, methadone, heroin; reaction to nitrofurantoin)

Drugs (OD of morphine, methadone, heroin; reaction to nitrofurantoin) Noxious inhalation (chlorine gas, high O2 concentration)

Noxious inhalation (chlorine gas, high O2 concentration) Post resuscitation

Post resuscitation Cardiopulmonary bypass

Cardiopulmonary bypass Pneumonia

Pneumonia TB

TB Burns

Burns Pancreatitis

PancreatitisDiagnosis

Labs

ABGs: initially, varying degrees of hypoxemia, generally resistant to supplemental O2; subsequently, respiratory alkalosis, ↓ PCO2, and widened alveolar-arterial gradient. Hypercapnia occurs as the disease progresses.

ABGs: initially, varying degrees of hypoxemia, generally resistant to supplemental O2; subsequently, respiratory alkalosis, ↓ PCO2, and widened alveolar-arterial gradient. Hypercapnia occurs as the disease progresses. Hemodynamic monitoring (when indicated): Although no hemodynamic profile is diagnostic of ARDS, the presence of pulmonary edema, CO, and ↓ PAWP is characteristic of ARDS.

Hemodynamic monitoring (when indicated): Although no hemodynamic profile is diagnostic of ARDS, the presence of pulmonary edema, CO, and ↓ PAWP is characteristic of ARDS.Imaging

CXR: Bilateral interstitial infiltrates are usually seen within 24 hr; they are often more prominent in the bases and periphery. Near-total “whiteout” of both lung fields can be seen in advanced stages.

CXR: Bilateral interstitial infiltrates are usually seen within 24 hr; they are often more prominent in the bases and periphery. Near-total “whiteout” of both lung fields can be seen in advanced stages.Treatment

Identification and Rx of the precipitating condition

Identification and Rx of the precipitating condition Fluid management: Optimal fluid management is pt specific. Swan-Ganz catheterization may be indicated and is useful to guide fluid replacement. A PCWP of approximately 12 mm Hg is ideal.

Fluid management: Optimal fluid management is pt specific. Swan-Ganz catheterization may be indicated and is useful to guide fluid replacement. A PCWP of approximately 12 mm Hg is ideal. DVT prophylaxis

DVT prophylaxis Stress ulcer prophylaxis w/sucralfate suspension (by NG tube) or IV PPIs or IV H2 blockers

Stress ulcer prophylaxis w/sucralfate suspension (by NG tube) or IV PPIs or IV H2 blockersF. Asthma

Definition

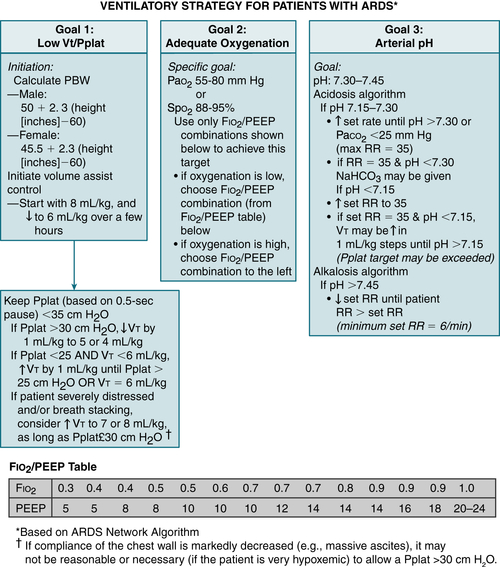

FIGURE 11-5 Ventilatory strategy for patients with ARDS. Several caveats should be considered when using the low VT strategy: (1) VT is based on predicted body weight (PBW), not actual body weight; PBW tends to be about 20% lower than actual BW; (2) the protocol mandates decreases in the VT lower than 6 mL/kg of PBW if the plateau pressure (Pplat) is greater than 30 cm H2O and allows for small increases in VT if the patient is severely distressed and/or if there is breath stacking, as long as Pplat remains at 30 cm H2O or lower; (3) because arterial CO2 levels will rise, pH will fall; acidosis is treated with increasingly aggressive strategies dependent on the arterial pH; (4) the protocol has no specific provisions for the patient with a stiff chest wall, which in this context refers to the rib cage and abdomen; in such patients, it seems reasonable to allow Pplat to increase to more than 30 cm H2O, even though it is not mandated by the protocol; in such cases, the limit on Pplat may be modified based on analysis of abdominal pressure, which can be estimated by measuring bladder pressure. (From Goldman L, Schafer AI [eds]: Goldman’s Cecil Medicine, 24th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2012.)

Diagnosis

For symptomatic adults and children aged >5 yr who can perform spirometry, asthma can be dx after H&P documenting an episodic pattern of respiratory sx and from spirometry that indicates partially reversible airflow obstruction (>12% and 200 mL in 1 FEV1 after inhaling a short bronchodilator or receiving a short [2-3 wk] course of PO corticosteroids).

For symptomatic adults and children aged >5 yr who can perform spirometry, asthma can be dx after H&P documenting an episodic pattern of respiratory sx and from spirometry that indicates partially reversible airflow obstruction (>12% and 200 mL in 1 FEV1 after inhaling a short bronchodilator or receiving a short [2-3 wk] course of PO corticosteroids).TABLE 11-5

Relative Severity of an Asthmatic Attack as Indicated by Peak Expiratory Flow Rate, FEV1, and Maximal Midexpiratory Flow Rate

| Test | Predicted Value (%) | Severity of Asthma |

| PEFR | >80 | |

| FEV1 | >80 | No spirometric abnormalities |

| MMEFR | >80 | |

| PEFR | >80 | |

| FEV1 | >70 | Mild asthma |

| MMEFR | 55-75 | |

| PEFR | >60 | |

| FEV1 | 45-70 | Moderate asthma |

| MMEFR | 30-50 | |

| PEFR | <50 | |

| FEV1 | <50 | Severe asthma |

| MMEFR | 10-30 |

From Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds): Goldman’s Cecil Medicine, 24th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2012. In Ferri F: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: 5 Books in 1. 2013 edition. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2012.

The degree of reversibility measured by spirometry correlates w/airway obstruction. Table 11-5 describes the relative severity of an asthmatic attack as indicated by PEFR, FEV1, and MMEFR.

The degree of reversibility measured by spirometry correlates w/airway obstruction. Table 11-5 describes the relative severity of an asthmatic attack as indicated by PEFR, FEV1, and MMEFR. Physical exam findings vary w/the stage and severity of asthma and may reveal only inspiratory and expiratory phases of respiration. Exam during status asthmaticus may reveal

Physical exam findings vary w/the stage and severity of asthma and may reveal only inspiratory and expiratory phases of respiration. Exam during status asthmaticus may reveal PFT’s show obstructive pattern

PFT’s show obstructive pattern Normal spirometry and high suspicion for asthma → bronchial challenge testing.

Normal spirometry and high suspicion for asthma → bronchial challenge testing. Wheezing: Absence of wheezing (silent chest) or ↓ wheezing can indicate worsening obstruction.

Wheezing: Absence of wheezing (silent chest) or ↓ wheezing can indicate worsening obstruction. ΔMS is generally secondary to hypoxia and hypercapnia and constitutes an indication for urgent intubation.

ΔMS is generally secondary to hypoxia and hypercapnia and constitutes an indication for urgent intubation. Paradoxical abd and diaphragmatic movement on inspiration (detected by palpation over the upper part of the abd in a semirecumbent position) is an important sign of impending respiratory crisis and indicates diaphragmatic fatigue.

Paradoxical abd and diaphragmatic movement on inspiration (detected by palpation over the upper part of the abd in a semirecumbent position) is an important sign of impending respiratory crisis and indicates diaphragmatic fatigue. The following abnlities in VS are indicative of severe asthma exacerbation:

The following abnlities in VS are indicative of severe asthma exacerbation:Labs

ABGs can be used in staging the severity of an asthmatic attack:

ABGs can be used in staging the severity of an asthmatic attack: Peak flow <40% or 40%-69% of patients personal best warrants increased frequency of scheduled and PRN SABA Rx as well as systemic steroids (quick taper preferred)

Peak flow <40% or 40%-69% of patients personal best warrants increased frequency of scheduled and PRN SABA Rx as well as systemic steroids (quick taper preferred)Imaging

CXR is usually nl but may show evidence of thoracic hyperinflation (e.g., flattening of the diaphragm, volume over the retrosternal air space).

CXR is usually nl but may show evidence of thoracic hyperinflation (e.g., flattening of the diaphragm, volume over the retrosternal air space). ECG: Tachycardia and nonspecific ST-T wave changes are common during an asthmatic attack; may also show cor pulmonale, RBBB, RAD, and counterclockwise rotation.

ECG: Tachycardia and nonspecific ST-T wave changes are common during an asthmatic attack; may also show cor pulmonale, RBBB, RAD, and counterclockwise rotation.Treatment

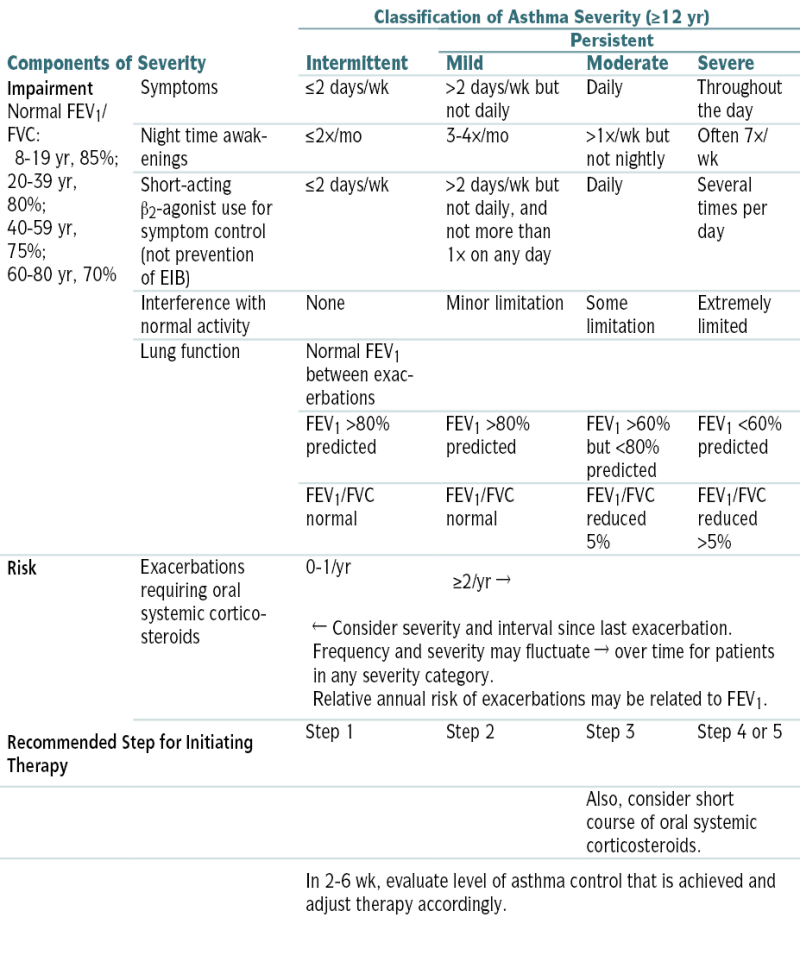

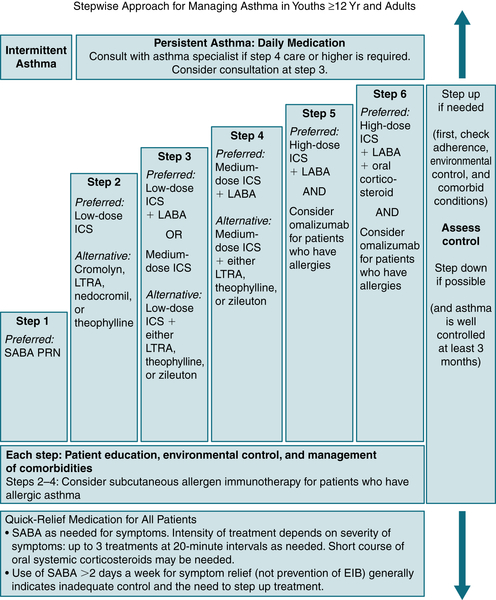

Table 11-6 describes the classification of asthma severity and therapeutic considerations. A stepwise approach for managing asthma in youths >12 yr and adults is described in Figure 11-7.

Table 11-6 describes the classification of asthma severity and therapeutic considerations. A stepwise approach for managing asthma in youths >12 yr and adults is described in Figure 11-7. The differentiation of asthma from COPD can be challenging. An hx of atopy and intermittent, reactive sx points toward a dx of asthma, whereas smoking and advanced age are more indicative of COPD. Spirometry is useful to distinguish asthma from COPD. Table 11-7 summarizes differentiating features of asthma and COPD.

The differentiation of asthma from COPD can be challenging. An hx of atopy and intermittent, reactive sx points toward a dx of asthma, whereas smoking and advanced age are more indicative of COPD. Spirometry is useful to distinguish asthma from COPD. Table 11-7 summarizes differentiating features of asthma and COPD.TABLE 11-6

Classifying Asthma Severity and Initiating Treatment in Youths ≥12 Yr and Adults∗

| Components of Severity | Classification of Asthma Severity (≥12 yr) | ||||

| Intermittent | Persistent | ||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | |||

| Impairment Normal FEV1/FVC: 8-19 yr, 85%; 20-39 yr, 80%; 40-59 yr, 75%; 60-80 yr, 70% |

Symptoms | ≤2 days/wk | >2 days/wk but not daily | Daily | Throughout the day |

| Night time awakenings | ≤2×/mo | 3-4×/mo | >1×/wk but not nightly | Often 7×/wk | |

| Short-acting β2-agonist use for symptom control (not prevention of EIB) | ≤2 days/wk | >2 days/wk but not daily, and not more than 1× on any day | Daily | Several times per day | |

| Interference with normal activity | None | Minor limitation | Some limitation | Extremely limited | |

| Lung function | Normal FEV1 between exacerbations | ||||

| FEV1 >80% predicted | FEV1 >80% predicted | FEV1 >60% but <80% predicted | FEV1 <60% predicted | ||

| FEV1/FVC normal | FEV1/FVC normal | FEV1/FVC reduced 5% | FEV1/FVC reduced >5% | ||

| Risk | Exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids | 0-1/yr | ≥2/yr → | ||

| ← Consider severity and interval since last exacerbation. Frequency and severity may fluctuate → over time for patients in any severity category. Relative annual risk of exacerbations may be related to FEV1. |

|||||

| Recommended Step for Initiating Therapy | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 or 5 | |

| Also, consider short course of oral systemic corticosteroids. | |||||

| In 2-6 wk, evaluate level of asthma control that is achieved and adjust therapy accordingly. | |||||

The stepwise approach is meant to assist, not replace, the clinical decision making required to meet individual patient needs.

Level of severity is determined by assessment of both impairment and risk. Assess impairment domain by patient’s/caregiver’s recall of previous 2-4 wk and spirometry. Assign severity to the most severe category in which any feature occurs.

At present, data are inadequate to correlate frequencies of exacerbation with different levels of asthma severity. In general, more frequent and intense exacerbations (e.g., requiring urgent, unscheduled care, hospitalization, or ICU admission) indicate greater underlying disease severity. For treatment purposes, patients who had ≥2 exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids in the past year may be considered the same as patients who have persistent asthma, even in the absence of impairment levels consistent with persistent asthma.

To access the complete Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma, go to www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf.

EIB, Exercise-induced bronchospasm

∗ Assessing severity and initiating treatment for patients who are not currently taking long-term control medications.

From National Asthma Education and Prevention Program: Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. NIH publication 08-4051. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 2007.

G. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Definition

FIGURE 11-7 Stepwise approach for managing asthma in youth ≥12 yr old and in adults. EIB, Exercise-induced bronchospasm; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, inhaled long-acting β2-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; SABA, inhaled short-acting β2-agonist. (From National Asthma Education and Prevention Program: Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. NIH publication 08-4051. Bethesda, Md, National Institutes of Health, 2007.)

TABLE 11-7

Differentiating Features of COPD and Asthma

| COPD | Asthma | |

| Smoker or ex-smoker | Most | Possibly |

| Symptoms <35 yr of age | Rare | Common |

| Atopic features (rhinitis, eczema) | Uncommon | Common |

| Cellular infiltrate | Macrophages, neutrophils, CD8+ T cells | Eosinophils, CD4+ T cells |

| Cough and sputum | Daily/common | Intermittent |

| Breathlessness | Persistent and progressive | Variable |

| Night time symptoms | Uncommon | Common |

| Significant diurnal or day-to-day variability of symptoms | Uncommon | Common |

| Bronchodilator response (FEV1 and PEFR) | <15% | >20% |

| Corticosteroid response | Poor | Good |

From Ballinger A: Kumar & Clark’s Essentials of Clinical Medicine, 5th ed. Edinburgh, Saunders, 2012.

TABLE 11-8

Classification of COPD Severity (GOLD Criteria)

| Stage | Function | Symptoms |

| Stage I: mild | FEV1/FVC <70% FEV1 ≥80% predicted |

Chronic cough, none/mild breathlessness |

| Stage II: moderate | FEV1/FVC <70% 50% ≤ FEV1 <80% predicted |

Breathlessness on exertion |

| Stage III: severe | FEV1/FVC <70% 30% ≤ FEV1 <50% predicted |

Breathless on minimal exertion; possible weight loss and depression |

| Stage IV: very severe | FEV1/FVC <70% FEV1 <30% predicted or FEV1 <50% predicted plus respiratory failure |

Breathless at rest |

Modified from Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Available at: www.goldcopd.com

Etiology

Tobacco exposure

Tobacco exposure Occupational exposure to pulmonary toxins (e.g., dust, noxious gases, vapors, fumes, cadmium, coal, silica). The industries w/the highest exposure risk are plastics, leather, rubber, and textiles.

Occupational exposure to pulmonary toxins (e.g., dust, noxious gases, vapors, fumes, cadmium, coal, silica). The industries w/the highest exposure risk are plastics, leather, rubber, and textiles. Atmospheric pollution

Atmospheric pollution AAT deficiency (<1% of pts w/COPD)

AAT deficiency (<1% of pts w/COPD)Diagnosis

H&P

Peripheral cyanosis, productive cough, tachypnea, tachycardia

Peripheral cyanosis, productive cough, tachypnea, tachycardia Dyspnea, pursed-lip breathing w/use of accessory muscles for respiration, ↓ breath sounds, wheezing

Dyspnea, pursed-lip breathing w/use of accessory muscles for respiration, ↓ breath sounds, wheezing Acute exacerbation of COPD is mainly a clinical dx and generally is manifested w/worsening dyspnea, sputum purulence, and volume.

Acute exacerbation of COPD is mainly a clinical dx and generally is manifested w/worsening dyspnea, sputum purulence, and volume.Classification

Imaging

CXR: hyperinflation w/flattened diaphragm, tenting of the diaphragm at the rib, and retrosternal chest space, ↑ AP diameter

CXR: hyperinflation w/flattened diaphragm, tenting of the diaphragm at the rib, and retrosternal chest space, ↑ AP diameter ↓ Vascular markings and bullae in pts w/“emphysema”

↓ Vascular markings and bullae in pts w/“emphysema” Thickened bronchial markings and enlarged right side of the heart in pts w/“chronic bronchitis”

Thickened bronchial markings and enlarged right side of the heart in pts w/“chronic bronchitis”Treatment

H. Pulmonary Vascular Disease

1. Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

Definition

Etiology

Risk factors for PE:

Risk factors for PE:TABLE 11-9

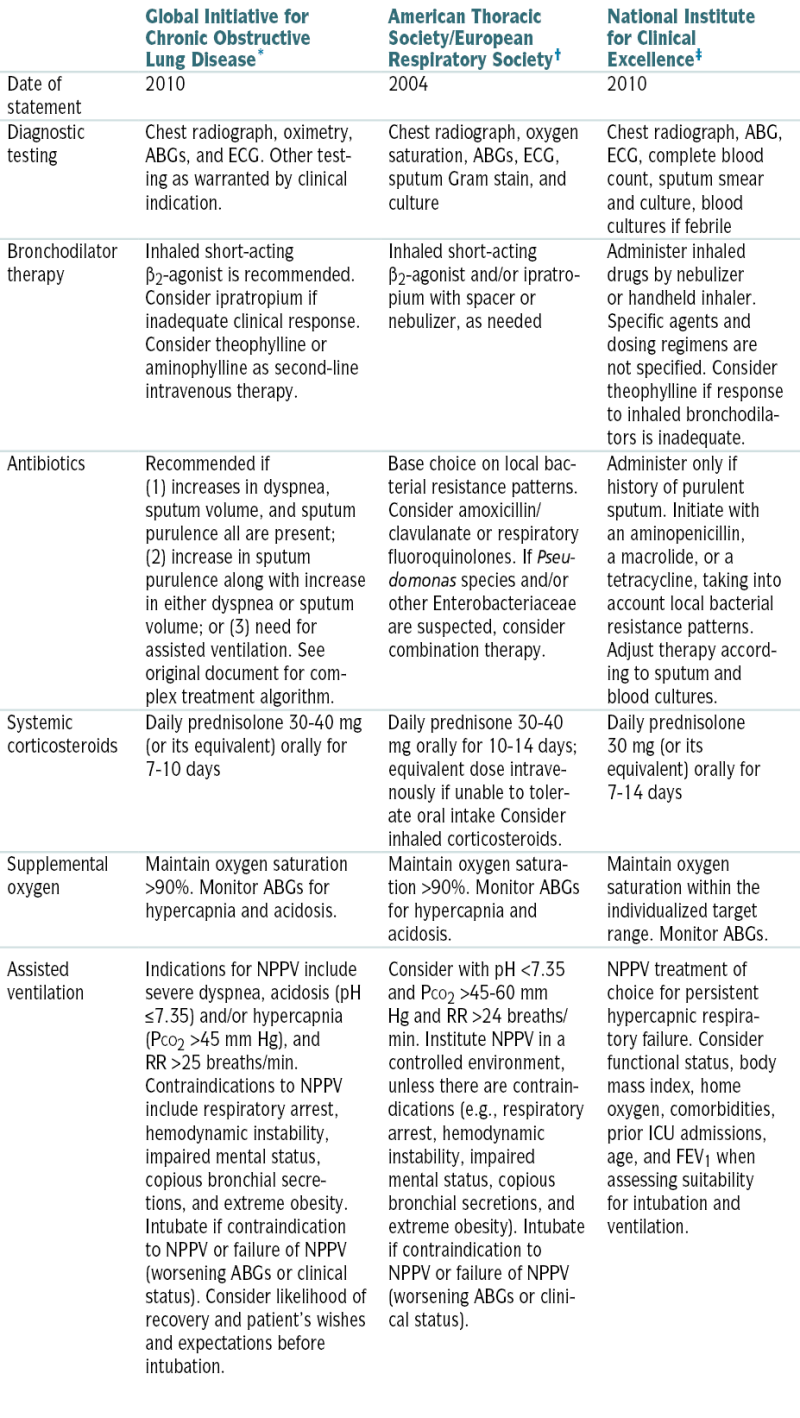

Guideline Recommendations for Hospital Management of COPD Exacerbations

| Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease∗ | American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society† | National Institute for Clinical Excellence‡ | |

| Date of statement | 2010 | 2004 | 2010 |

| Diagnostic testing | Chest radiograph, oximetry, ABGs, and ECG. Other testing as warranted by clinical indication. | Chest radiograph, oxygen saturation, ABGs, ECG, sputum Gram stain, and culture | Chest radiograph, ABG, ECG, complete blood count, sputum smear and culture, blood cultures if febrile |

| Bronchodilator therapy | Inhaled short-acting ß2-agonist is recommended. Consider ipratropium if inadequate clinical response. Consider theophylline or aminophylline as second-line intravenous therapy. | Inhaled short-acting ß2-agonist and/or ipratropium with spacer or nebulizer, as needed | Administer inhaled drugs by nebulizer or handheld inhaler. Specific agents and dosing regimens are not specified. Consider theophylline if response to inhaled bronchodilators is inadequate. |

| Antibiotics | Recommended if (1) increases in dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence all are present; (2) increase in sputum purulence along with increase in either dyspnea or sputum volume; or (3) need for assisted ventilation. See original document for complex treatment algorithm. | Base choice on local bacterial resistance patterns. Consider amoxicillin/clavulanate or respiratory fluoroquinolones. If Pseudomonas species and/or other Enterobacteriaceae are suspected, consider combination therapy. | Administer only if history of purulent sputum. Initiate with an aminopenicillin, a macrolide, or a tetracycline, taking into account local bacterial resistance patterns. Adjust therapy according to sputum and blood cultures. |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Daily prednisolone 30-40 mg (or its equivalent) orally for 7-10 days | Daily prednisone 30-40 mg orally for 10-14 days; equivalent dose intravenously if unable to tolerate oral intake Consider inhaled corticosteroids. | Daily prednisolone 30 mg (or its equivalent) orally for 7-14 days |

| Supplemental oxygen | Maintain oxygen saturation >90%. Monitor ABGs for hypercapnia and acidosis. | Maintain oxygen saturation >90%. Monitor ABGs for hypercapnia and acidosis. | Maintain oxygen saturation within the individualized target range. Monitor ABGs. |

| Assisted ventilation | Indications for NPPV include severe dyspnea, acidosis (pH ≤7.35) and/or hypercapnia (PCO2 >45 mm Hg), and RR >25 breaths/min. Contraindications to NPPV include respiratory arrest, hemodynamic instability, impaired mental status, copious bronchial secretions, and extreme obesity. Intubate if contraindication to NPPV or failure of NPPV (worsening ABGs or clinical status). Consider likelihood of recovery and patient’s wishes and expectations before intubation. | Consider with pH <7.35 and PCO2 >45-60 mm Hg and RR >24 breaths/min. Institute NPPV in a controlled environment, unless there are contraindications (e.g., respiratory arrest, hemodynamic instability, impaired mental status, copious bronchial secretions, and extreme obesity). Intubate if contraindication to NPPV or failure of NPPV (worsening ABGs or clinical status). | NPPV treatment of choice for persistent hypercapnic respiratory failure. Consider functional status, body mass index, home oxygen, comorbidities, prior ICU admissions, age, and FEV1 when assessing suitability for intubation and ventilation. |

∗ Data from http://www.goldcopd.com.

† Data from MacNee W: Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 23:932-946, 2004.

‡ Data from http://www.nice.org.uk.

From Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds): Goldman’s Cecil Medicine, 24th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2012.

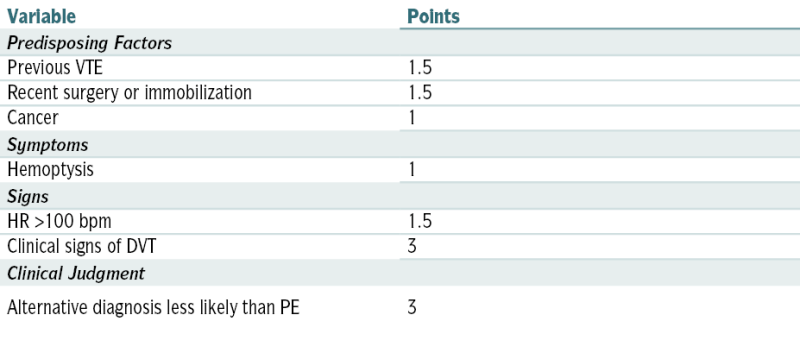

TABLE 11-10

Wells Clinical Prediction Rule for Likelihood of Pulmonary Embolism

| Variable | Points |

| Predisposing Factors | |

| Previous VTE | 1.5 |

| Recent surgery or immobilization | 1.5 |

| Cancer | 1 |

| Symptoms | |

| Hemoptysis | 1 |

| Signs | |

| HR >100 bpm | 1.5 |

| Clinical signs of DVT | 3 |

| Clinical Judgment | |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3 |

| Clinical Probability | Total Points |

| Low | <2 |

| Moderate | 2-6 |

| High | >6 |

Modified from Wells PS, Ginsberg JS, Anderson DR, et al: Use of a clinical model for safe management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med 129:997-1005, 1998.

Diagnosis

H&P

Most common physical finding: tachypnea

Most common physical finding: tachypnea Chest pain: may be nonpleuritic or pleuritic (infarction)

Chest pain: may be nonpleuritic or pleuritic (infarction) Syncope (massive PE)

Syncope (massive PE) Hemoptysis, cough

Hemoptysis, cough Evidence of DVT: may be present (e.g., swelling and tenderness of extremities)

Evidence of DVT: may be present (e.g., swelling and tenderness of extremities) Cardiac exam: tachycardia, pulmonic component of S2, murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, RV heave, right-sided S3

Cardiac exam: tachycardia, pulmonic component of S2, murmur of tricuspid insufficiency, RV heave, right-sided S3 Pulmonary exam: rales, localized wheezing, friction rub

Pulmonary exam: rales, localized wheezing, friction rubLabs

ABGs: ↓ PaO2 and PaCO2, ↑ pH

ABGs: ↓ PaO2 and PaCO2, ↑ pH A-a O2 gradient (measure of the difference in O2 concentration between alveoli and arterial blood): An nl A-a gradient makes the dx of PE unlikely.

A-a O2 gradient (measure of the difference in O2 concentration between alveoli and arterial blood): An nl A-a gradient makes the dx of PE unlikely. Plasma D-dimer by ELISA: An nl plasma D-dimer level is useful to r/o PE in pts w/nondiagnostic lung scan and a low pretest probability of PE. However, it cannot “rule in” PE because it is ↑ w/many other disorders (e.g., metastatic cancer, trauma, sepsis, postoperative state).

Plasma D-dimer by ELISA: An nl plasma D-dimer level is useful to r/o PE in pts w/nondiagnostic lung scan and a low pretest probability of PE. However, it cannot “rule in” PE because it is ↑ w/many other disorders (e.g., metastatic cancer, trauma, sepsis, postoperative state).Imaging

CXR: ↑ diaphragm, pleural effusion, dilation of pulmonary artery, infiltrate or consolidation, abrupt vessel cutoff, or atelectasis. A wedge-shaped consolidation in the middle and lower lobes suggests a pulmonary infarction and is known as Hampton’s hump.

CXR: ↑ diaphragm, pleural effusion, dilation of pulmonary artery, infiltrate or consolidation, abrupt vessel cutoff, or atelectasis. A wedge-shaped consolidation in the middle and lower lobes suggests a pulmonary infarction and is known as Hampton’s hump. Spiral CT: excellent modality for dx PE (Fig. 11-8). It can also detect other pulmonary disease that can mimic PE.

Spiral CT: excellent modality for dx PE (Fig. 11-8). It can also detect other pulmonary disease that can mimic PE. Lung scan (in pt w/nl CXR):

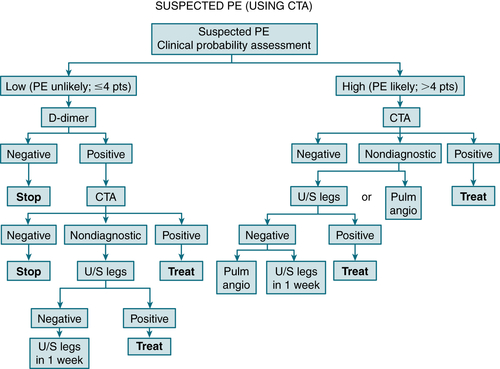

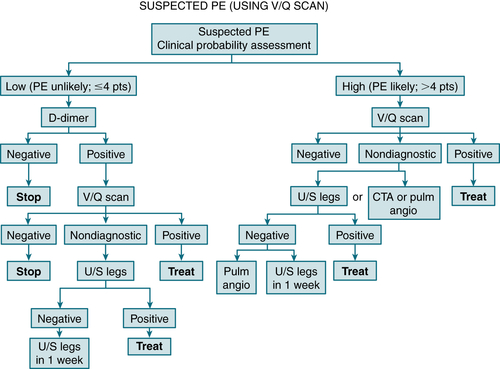

Lung scan (in pt w/nl CXR): Figure 11-9 is a diagnostic algorithm incorporating the Wells criteria, D-dimer testing, and V/Q scan.

Figure 11-9 is a diagnostic algorithm incorporating the Wells criteria, D-dimer testing, and V/Q scan.

FIGURE 11-8 Integrated strategy for diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE) using clinical probability assessment, measurement of D-dimer, and computer tomography angiography (CTA) as primary imaging test. Patients with low clinical probability (i.e., PE unlikely, negative D-dimer) need no further testing, but if D-dimer is positive, they should proceed to CTA, and if this is nondiagnostic, to ultrasonography of legs. Then either treat or repeat ultrasound in 1 week. Patients with high clinical probability (i.e., PE likely) need not have D-dimer measure but should proceed directly to CTA. If CTA is not diagnostic, options are to perform ultrasonography of legs or proceed to pulmonary angiogram. If ultrasound of legs is negative, options are to repeat in 1 week or proceed to pulmonary angiography. (From Vincent JL, Abraham E, Moore FA, et al [eds]: Textbook of Critical Care, 6th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2011.)

FIGURE 11-9 Integrated strategy for diagnosis of suspected PE using clinical probability assessment, measurement of D-dimer, and V/Q scan as primary imaging test. Patients with low clinical probability (i.e., PE unlikely, negative D-dimer) need no further investigation. If D-dimer is positive, V/Q scan performed; if not diagnostic, proceed to ultrasound. Then either treat or repeat ultrasound in 1 week. Patients with high probability (i.e., PE likely) need not have D-dimer measured but should proceed directly to V/Q scan. If V/Q scan not diagnostic, options are to perform CTA, pulmonary angiography, or ultrasonography of legs. If ultrasonography is negative, either repeat in 1 week or perform pulmonary angiogram. (From Vincent JL, Abraham E, Moore FA, et al [eds]: Textbook of Critical Care, 6th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2011.)

Angiography: Pulmonary angiography is the gold standard; however, it is invasive, expensive, and not readily available in some clinical settings. False(+) pulmonary angiograms may result from mediastinal disorders such as radiation fibrosis and tumors.

Angiography: Pulmonary angiography is the gold standard; however, it is invasive, expensive, and not readily available in some clinical settings. False(+) pulmonary angiograms may result from mediastinal disorders such as radiation fibrosis and tumors. CTA is an accurate, noninvasive tool in the dx of PE at the main, lobar, and segmental pulmonary artery levels. A major advantage of CTA over standard pulmonary angiography is its ability to dx intrathoracic disease other than PE that may account for the pt’s clinical picture. It is also less invasive, less costly, and more widely available. Its major shortcoming is its poor sensitivity for subsegmental emboli. It is contraindicated in patients with GFR<30/renal failure.

CTA is an accurate, noninvasive tool in the dx of PE at the main, lobar, and segmental pulmonary artery levels. A major advantage of CTA over standard pulmonary angiography is its ability to dx intrathoracic disease other than PE that may account for the pt’s clinical picture. It is also less invasive, less costly, and more widely available. Its major shortcoming is its poor sensitivity for subsegmental emboli. It is contraindicated in patients with GFR<30/renal failure. Gadolinium-enhanced MRA of the pulmonary arteries has a moderate sensitivity and high specificity for the dx of PE; MRA is best reserved for selected pts when CT scan and lung scan are inconclusive and the risk of pulmonary angiography is high.

Gadolinium-enhanced MRA of the pulmonary arteries has a moderate sensitivity and high specificity for the dx of PE; MRA is best reserved for selected pts when CT scan and lung scan are inconclusive and the risk of pulmonary angiography is high. ECG: abnl in 85% of pts w/acute PE. Frequent abnlities are sinus tachycardia; S1,Q3,T3 pattern (10% of pts); S1,S2,S3 pattern; T wave inversion in V1 to V6; acute RBBB; new-onset AF; ST-segment depression in lead II; RV strain.

ECG: abnl in 85% of pts w/acute PE. Frequent abnlities are sinus tachycardia; S1,Q3,T3 pattern (10% of pts); S1,S2,S3 pattern; T wave inversion in V1 to V6; acute RBBB; new-onset AF; ST-segment depression in lead II; RV strain.Treatment

See the section on venous thromboembolism in Chapter 7 for Rx of PE.

See the section on venous thromboembolism in Chapter 7 for Rx of PE. Acute pulmonary artery embolectomy may be indicated in a pt w/massive PE and refractory hypotension.

Acute pulmonary artery embolectomy may be indicated in a pt w/massive PE and refractory hypotension.2. Pulmonary Hypertension

Definition

Etiology and Classification

Diagnosis

H&P

Exertional dyspnea: most common presenting sx (60%)

Exertional dyspnea: most common presenting sx (60%) Fatigue and weakness

Fatigue and weakness Syncope, classically exertion related or after a warm shower w/peripheral vasodilation

Syncope, classically exertion related or after a warm shower w/peripheral vasodilation Chest pain

Chest pain Hoarse voice from compression of recurrent laryngeal nerve by an enlarged pulmonary artery (Ortner’s syndrome)

Hoarse voice from compression of recurrent laryngeal nerve by an enlarged pulmonary artery (Ortner’s syndrome) Loud P2 component of the second heart sound and paradoxical splitting of second heart sound

Loud P2 component of the second heart sound and paradoxical splitting of second heart sound Right-sided S4

Right-sided S4 JVD

JVD Abd distention/ascites

Abd distention/ascites Prominent parasternal (RV) impulse

Prominent parasternal (RV) impulse Holosystolic TR murmur heard best along the left fourth parasternal line that ↑ in intensity w/inspiration

Holosystolic TR murmur heard best along the left fourth parasternal line that ↑ in intensity w/inspiration Peripheral edema

Peripheral edemaLabs

CBC: nl or may show secondary polycythemia

CBC: nl or may show secondary polycythemia ANA (r/o connective tissue disease), HIV, LFTs, antiphospholipid Abs

ANA (r/o connective tissue disease), HIV, LFTs, antiphospholipid Abs ABGs: ↓ PO2 and SaO2

ABGs: ↓ PO2 and SaO2 PFTs: r/o obstructive or restrictive lung disease

PFTs: r/o obstructive or restrictive lung disease Overnight sleep study: r/o sleep apnea/hypopnea

Overnight sleep study: r/o sleep apnea/hypopneaImaging

ECG: RA enlargement (tall P wave >2.5 mV in leads II, III, aVF) and RV enlargement (RAD >100 and R wave > S wave in lead V1)

ECG: RA enlargement (tall P wave >2.5 mV in leads II, III, aVF) and RV enlargement (RAD >100 and R wave > S wave in lead V1) CXR: enlargement of the main and hilar pulmonary arteries w/rapid tapering of the distal vessels, described as peripheral oligemia. RV enlargement may be evident on lateral films.

CXR: enlargement of the main and hilar pulmonary arteries w/rapid tapering of the distal vessels, described as peripheral oligemia. RV enlargement may be evident on lateral films. Spiral CT or V/Q scan: r/o PE

Spiral CT or V/Q scan: r/o PE Doppler echo: assesses ventricular function, excludes significant valvular disease, and visualizes abnl shunting of blood between heart chambers if present. It also provides an estimate of the pulmonary artery systolic pressure.

Doppler echo: assesses ventricular function, excludes significant valvular disease, and visualizes abnl shunting of blood between heart chambers if present. It also provides an estimate of the pulmonary artery systolic pressure.TABLE 11-11

Updated Clinical Classification of Pulmonary Hypertension

ALK1, Activin receptor-like kinase type 1; BMPR2, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2.

Modified From Simonneau G et al: Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 54:S43-S54, 2009.

Treatment

Acute Rx

Diuretics (e.g., furosemide 40-80 mg qd)

Diuretics (e.g., furosemide 40-80 mg qd) Digoxin in pts w/AF

Digoxin in pts w/AF Short-acting vasodilators: IV adenosine, epoprostenol, or inhaled nitric oxide

Short-acting vasodilators: IV adenosine, epoprostenol, or inhaled nitric oxideChronic Rx

CCB (diltiazem, amlodipine, or nifedipine)

CCB (diltiazem, amlodipine, or nifedipine) Prostanoids (epoprostenol, treprostinil, and iloprost) act as potent vasodilators of pulmonary arteries and inhibitors of Plt aggregation.

Prostanoids (epoprostenol, treprostinil, and iloprost) act as potent vasodilators of pulmonary arteries and inhibitors of Plt aggregation. Endothelin receptor antagonists: bosentan, ambrisentan, and sitaxsentan

Endothelin receptor antagonists: bosentan, ambrisentan, and sitaxsentan Phosphodiesterase inhibitors: sildenafil and tadalafil

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors: sildenafil and tadalafil Warfarin Rx w/goal INR 1.5 to 2.0 is recommended for all pts w/PPH and although not proven may be indicated in secondary pulmonary HTN.

Warfarin Rx w/goal INR 1.5 to 2.0 is recommended for all pts w/PPH and although not proven may be indicated in secondary pulmonary HTN. Lung transplantation and heart-lung transplantation are other options in pts w/end-stage class IV disease. Atrial septostomy may be performed as a bridge to transplantation.

Lung transplantation and heart-lung transplantation are other options in pts w/end-stage class IV disease. Atrial septostomy may be performed as a bridge to transplantation.TABLE 11-12

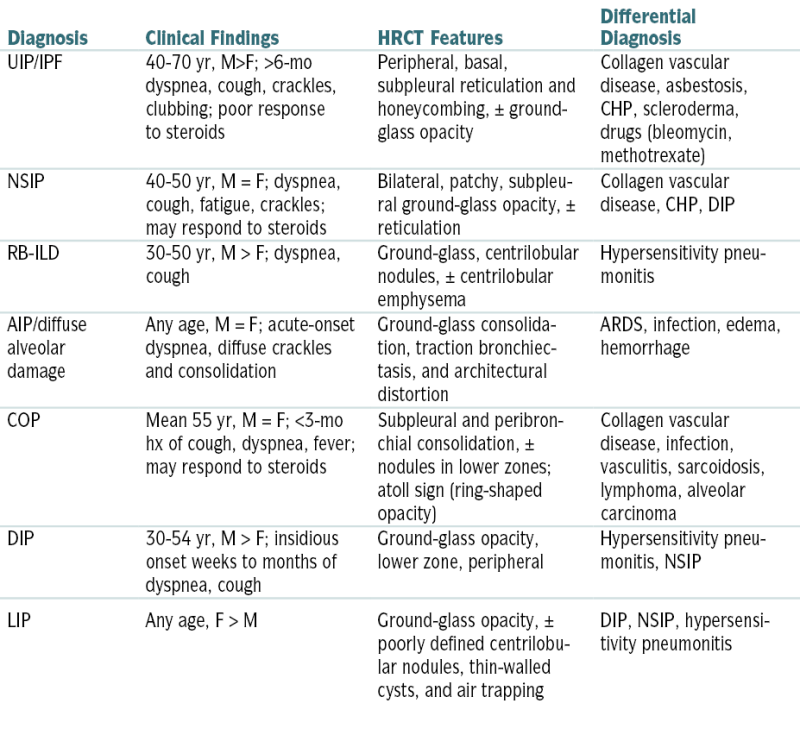

Overview of Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

| Diagnosis | Clinical Findings | HRCT Features | Differential Diagnosis |

| UIP/IPF | 40-70 yr, M>F; >6-mo dyspnea, cough, crackles, clubbing; poor response to steroids | Peripheral, basal, subpleural reticulation and honeycombing, ± ground-glass opacity | Collagen vascular disease, asbestosis, CHP, scleroderma, drugs (bleomycin, methotrexate) |

| NSIP | 40-50 yr, M = F; dyspnea, cough, fatigue, crackles; may respond to steroids | Bilateral, patchy, subpleural ground-glass opacity, ± reticulation | Collagen vascular disease, CHP, DIP |

| RB-ILD | 30-50 yr, M > F; dyspnea, cough | Ground-glass, centrilobular nodules, ± centrilobular emphysema | Hypersensitivity pneumonitis |

| AIP/diffuse alveolar damage | Any age, M = F; acute-onset dyspnea, diffuse crackles and consolidation | Ground-glass consolidation, traction bronchiectasis, and architectural distortion | ARDS, infection, edema, hemorrhage |

| COP | Mean 55 yr, M = F; <3-mo hx of cough, dyspnea, fever; may respond to steroids | Subpleural and peribronchial consolidation, ± nodules in lower zones; atoll sign (ring-shaped opacity) | Collagen vascular disease, infection, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, alveolar carcinoma |

| DIP | 30-54 yr, M > F; insidious onset weeks to months of dyspnea, cough | Ground-glass opacity, lower zone, peripheral | Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, NSIP |

| LIP | Any age, F > M | Ground-glass opacity, ± poorly defined centrilobular nodules, thin-walled cysts, and air trapping | DIP, NSIP, hypersensitivity pneumonitis |

AIP, Acute interstitial pneumonia; CHP, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; COP, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia; DIP, desquamative interstitial pneumonitis; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; RB-ILD, respiratory bronchiolitis–associated interstitial lung disease; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

From Ferri F: Ferri’s Clinical Advisor: 5 Books in 1. 2013 edition. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2012.

I. Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease

1. Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD)

Diagnosis

H&P

Dyspnea

Dyspnea Tachypnea

Tachypnea Bibasilar end-inspiratory dry crackles

Bibasilar end-inspiratory dry crackles Pulmonary HTN

Pulmonary HTN Cyanosis, clubbing

Cyanosis, clubbingLabs

ABGs: nl or may show respiratory alkalosis

ABGs: nl or may show respiratory alkalosis ANA, ANCA, ACE level, RF, LDH

ANA, ANCA, ACE level, RF, LDH Bronchoscopy and BAL may help identify type of ILD. However, their role in defining the stage of disease and the response to Rx is controversial.

Bronchoscopy and BAL may help identify type of ILD. However, their role in defining the stage of disease and the response to Rx is controversial. Bx is the most effective method for confirming dx and assessing disease activity.

Bx is the most effective method for confirming dx and assessing disease activity.Imaging (Box 11-5)

CXR, HRCT: bibasilar reticular pattern

CXR, HRCT: bibasilar reticular pattern PFTs: Well-defined patterns in PFTs are usually consistent w/restrictive defect (↓ FRC, RV, and TLC) resulting from ↓ lung compliance caused by alveolar wall thickening from inflammation and fibrosis. Diffusing capacity ↓ from inflammation and thickening of alveolar walls, although nonspecific. FEV1/FVC is usually nl or because lung stiffness keeps small airways open, although some conditions (e.g., sarcoidosis) may ↓ airflow.

PFTs: Well-defined patterns in PFTs are usually consistent w/restrictive defect (↓ FRC, RV, and TLC) resulting from ↓ lung compliance caused by alveolar wall thickening from inflammation and fibrosis. Diffusing capacity ↓ from inflammation and thickening of alveolar walls, although nonspecific. FEV1/FVC is usually nl or because lung stiffness keeps small airways open, although some conditions (e.g., sarcoidosis) may ↓ airflow.