12 Pulling it together

The Western therapist

The Western approach is summed up perfectly by the following quotation:

Acupuncture is a valuable method of complementary medicine with broad application in neurology. It is based on the experiences of traditional Chinese medicine as well as on experimentally proven biological (biochemical and neurophysiological) effects. Acupuncture-induced analgesia is mediated by inhibition of pain transmission at a spinal level and activation of central pain-modulating centers by release of opioids and other peptides that can be prevented by opioid antagonists (naloxone). Modern neuroimaging methods (functional MRI) confirmed the activation of subcortical and cortical centers, while transcranial Doppler sonography and SPECT showed an increase of cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen supply in normal subjects. Clinical experience and controlled studies confirmed the efficacy of acupuncture in various pain syndromes (tension headache, migraine, trigeminal neuralgia, posttraumatic pain, lumbar syndrome, ischialgia, etc.) and suggest favorable effects in the rehabilitation of peripheral facial nerve palsy and after stroke. Appropriate techniques, hygiene safeguards and knowledge of contraindications will minimize the risks of rare side effects of acupuncture which represents a valuable adjunction to the treatment repertoire in modern neurology. There is sufficient evidence of acupuncture to expand its use into conventional medicine and to encourage further studies of its pathophysiology and clinical value [2].

Although broadly encouraging, this raises a number of questions, the first being safety. Are we certain that acupuncture is safe? We do have results from a couple of very important safety trials, mentioned elsewhere in this book [3, 4], which support clinical practice and we also have additional anatomical work where skeletal anomalies have been examined and confirmed for prevalence. The two most important are the possibility of a sternal foramen at the level of CV 17 Shanzhong, and the thinning and occasional hole in the subspinal area of the scapula [5]. Once aware of the existence of these problems, and recognizing that the general bulk of muscle tissue can be greatly diminished in neurological disease, needling can be adjusted to avoid inflicting damage to the patient in any way.

Other safety issues are concerned with the physiological actions of acupuncture, such as increases in blood flow and velocity, sudden changes in blood pressure, unrealistic expectations produced by pain relief or euphoric responses to needling. Reviews of safety have concluded that, while acupuncture is not free of adverse events, they are rare, and it remains a relatively safe procedure [6].

It is also worth remembering that some of the recorded side-effects of acupuncture can be positive, the chief among them being described in a study of acupuncture as used by Swedish physiotherapists as ‘a pleasant feeling of fatigue’ [7].

Western supporting techniques

Ear acupuncture

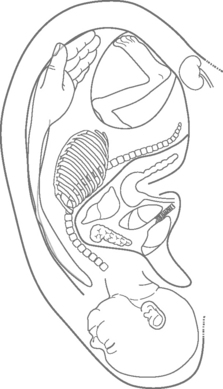

The ancient Chinese recognized that some channels passed around or through the ear and described all the Yang meridians as having some connection but had not fully appreciated the reflexes involved. Nogier on the other hand spent many years studying the ear and slowly built up his concept of the ‘man in the ear’, in which he described a human fetus in an upside-down position with the head in the region of the earlobe and the limbs towards the top of the ear (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 • ‘The man in the ear’ according to Nogier.

(From Hopwood V. Acupuncture in Physiotherapy. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004, p. 142.)

Nogier postulated that if there is a change in the body system due to pathology then a corresponding change can be shown in the ear, on the appropriate region. In the case of pain the areas where pain is felt in the body have been shown to have a high correlation with tenderness in the points on the ear that correspond with the sites. Oleson et al. provided the statistical evidence for these defined regions with a 74% accuracy rate in defining the musculoskeletal pains of 40 patients [8]. This applies to many kinds of pathology, not just pain [9]. The area occupied on the ear surface is proportional to that in the cortex, so the upper limb, particularly the hand and face, seems well represented.

The standardization of nomenclature for ear acupuncture points has been slow: the two main schools, that of Nogier and the TCM point locations, have now been joined by the work of Frank and Soliman [10, 11] who built on the original Nogier extended work which described three basic phases – mesodermal, ectodermal and endodermal. The theory underlying this division is that the ear is composed of three different kinds of tissue in the developing embryo and each of these types is involved in differing somatotropic responses relating to the ear. Further, the different phases are associated with acute, intermediate and chronic pain conditions. An acupuncture atlas [12] just gives all the points with little or no explanation, leading to much confusion among students.

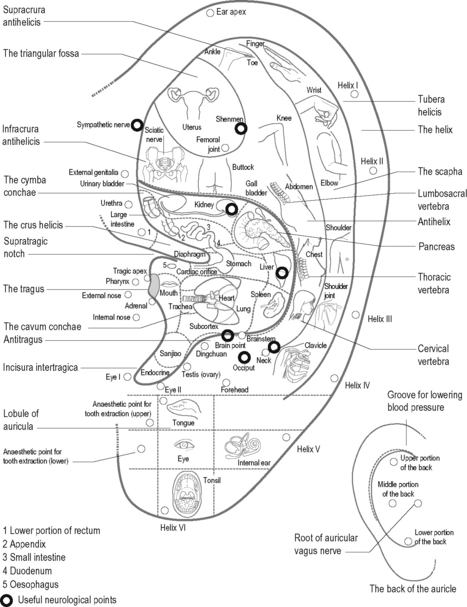

The Chinese ear charts differ quite radically from those produced by Nogier, leading to considerable confusion among acupuncturists (Figure 12.2). There are many points on the TCM ear, located by way of a grid system and requiring a fine location skill. Chinese texts recommend the use of the points according to TCM principles, i.e. the Kidney point to treat bones, but since this appears to be a true reflex system this use is not supported scientifically.

Figure 12.2 • Chinese map of ear points

(from Hopwood V. Acupuncture in Physiotherapy. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004, p. 14.)

More important is the nerve supply to each part of the structure. The ear has an abundant innervation, being supplied by the sensory fibres of the trigeminal, facial and vagus nerves. The endings of these nerves are closely interwoven and can influence many distant body areas. Bourdiol gives an explanation based on embryology, emphasizing the fact that these nerves travel only a short distance to the reticular formation of the brainstem [13].

There are several ways of classifying the points. Oleson and Kroening [14] suggested nomenclature that depends on whether the points are located on raised, depressed or hidden areas in the ear. Otherwise the Chinese or Nogier maps are commonly used.

The mechanism appears to be the same as in the rest of the body. Ear acupuncture has been shown to affect the endorphin concentration and to be reversible by naloxone [15]. The study by Simmons and Oleson investigated changes in dental pain threshold after electroacupuncture stimulation to the ear, showing that true electroacupuncture produced a significant rise in the pain threshold while the placebo, using inappropriate ear points, did not.

Points derived from the Chinese system of ear acupuncture are regularly used in drug addiction withdrawal programmes. The National Acupuncture Detoxification Association protocol uses five points – Shenmen, Liver, Lung, Sympathetic and Kidney – and is supported by some research [16]. This combination of points can produce profound relaxation in distressed patients so it has an application beyond that of drug withdrawal. It may owe more to the fact that the pinna is richly innervated and offers a good site to stimulate the central nervous system in a general way, but it has been utilized successfully in palliative care patients with serious anxiety states.

Research

The original work supporting this theory was performed by Oleson et al. [8]. In a blinded trial it was found that body pathology in patients could be detected with 74% accuracy by testing for tenderness in the ear and measuring changes in the electrical resistance of the skin. The result was highly statistically significant and anecdotal evidence from the same trial indicated that old pathology that the patients themselves had forgotten about was also detected.

A more recent study has taken this apparent correlation further. Given that the pathology of a particular organ appears to give rise to changes in the electrical impedance of the skin on the ear over the corresponding point, the researchers tested the validity of this reflex with patients undergoing surgery [17]. Forty-five patients, admitted for surgery for cholecystectomy, appendectomy, partial gastrectomy or dilatation and curettage after miscarriage, were tested. The initial value of skin resistance was estimated at the auricular organ projection area on five occasions: (1) before premedication; (2) after medication; (3) under general anaesthesia; (4) after skin incision; and (5) after surgery. Two healthy organ projection areas were measured on each patient each time as a control. The examiners performed all measurements without knowledge of the corresponding points.

Of more relevance to neurological disease, a recent systematic review has now indicated that auricular acupuncture appears to be effective for treating insomnia [18]. Ear acupuncture is a useful addition to the needling skills of a physiotherapist. It seems to have a reasonable evidence base and lends itself to use on nervous or debilitated patients. Since it can also be utilized in patients where access to the normal body points is not possible for some reason, for instance in cases of pain after major surgery, during childbirth or extensive application of plaster fixation, it can be versatile. It also provides a means of treating a patient where mobilization is difficult and normal transition from chair to bed presents problems with increased muscle tone.

Trigger point acupuncture

Myofascial pain, commonly treated by trigger point needling, appears to be modulated by local or segmental effects, perhaps not always requiring a fully intact nervous system. It is worth noting that the myofascial pain points described as trigger points often correlate with traditional acupuncture points [19]. The best textbook, detailing both patterns and treatment techniques, is that by Peter Baldry [20] describing a minimally invasive form of needling which can be very effective and often preferable to the deeper kind when treating neurogenic conditions.

Superficial needling [20]

The trigger point is first palpated. Either the patient may exhibit a disproportional response, the so-called ‘jump and shout’ response, and/or the operator may be able to palpate a taut band in the muscle. Using a short needle, the point is introduced subdermally and the needle allowed to fall against the skin. No manipulation is given and the Deqi sensation is not elicited. This needle is retained for only 30 seconds, removed and then the point is palpated again. If the sensation remains unchanged, the needle can be reinserted (provided it has not been in contact with anything else in the meantime) and left for a further 30 seconds before final removal. This often appears to deactivate the tender trigger point after the first application [21].

Deep trigger point needling [22]

This involves deep needling into the palpated taut band and a visible muscle twitch is often produced. Quite a long needle is used and, to facilitate easy insertion and prevent contact with the shaft of the needle, a tubular guide is used. Needle grasp conforms to muscular spasm and the accuracy of the insertion. The patient experiences a strong sensation rather like a muscle cramp which can be very painful but does guarantee the eventual success of the intervention. The needle is vigorously manipulated. This manipulation is aimed at disrupting the dysfunctional endplates in order to provoke a healing response. The needle is left for 10–20 minutes and then removed once relaxation has occurred. This may be obtained more quickly with manual stimulation, particularly with ‘pecking’ movements, although it may cause the spasm to intensify initially. Although placing the needle at the motor zone or musculotendinous junction is most effective for releasing spasm, in neuropathy extrajunctional acetylcholine receptors or ‘hot spots’ are formed throughout the entire length of the muscle. Thus a needle inserted almost anywhere into a shortened muscle can relieve spasm [23].

Recently published work [24] has offered links between the distal acupuncture points and changes in the painful loci within the trigger point regions. These loci are probably located in the endplate zone and endplate ‘noise’ in trapezius muscles in patients with chronic pain has been shown to decrease after acupuncture is applied to Waiguan and Quchi. The story is not yet fully explored and use of the major distal points remains important whichever school of acupuncture is followed.

Electroacupuncture

Electroacupuncture involves the electrical stimulation of acupuncture points by passing a current through acupuncture needles. It was developed into its modern form in China in the 1950s, when it was used for surgical anaesthesia. Since then it has been used for acupuncture analgesia and many other clinical presentations. It allows the provision of a stronger, more continuous level of stimulation and can be less time-consuming for the practitioner. In some conditions it may produce more rapid and prolonged treatment effects. This form of acupuncture is widely used in research studies since the level of stimulation provided may be carefully standardized [25].

Application of electroacupuncture

The effects of electroacupuncture are influenced by the frequency of stimulation used and the intensity selected. The application of low frequencies of 2–8 Hz will stimulate small-diameter afferent fibres and provide analgesic effects by the release of β-endorphin, enkephalin and orphanin, whilst high frequency, of 80–100 Hz, stimulates large afferent fibres, causing the release of dynorphin [26]. Other neurotransmitters are released and probably include noradrenaline (norepinephrine), dopamine and serotonin [25]. Intensity of stimulation may be varied.

Electroacupuncture in neurological conditions

Electroacupuncture has been used widely for neurological conditions in China and has also been used in many of the research trials on acupuncture for stroke. Studies relevant to neurological conditions have been considered in Chapter 4. In practical terms electroacupuncture seems to be useful for sensory and motor problems. Evidence shows that lack of afferent information from areas of impaired sensation or movement results in reorganization of cortical maps. Interventions to increase somatosensory stimulation are being used increasingly to influence sensory and motor function, with promising results in some studies [27]. Electroacupuncture could provoke a strong stimulus in this regard, providing afferent information from skin and muscle contraction.

Contraindications and safety specific to neurological conditions

In addition to the usual contraindications and precautions there are particular considerations when using electroacupuncture in neurological conditions. Electroacupuncture may be used in well-controlled epilepsy with caution, although the option of choice would be manual acupuncture. Strong or sustained muscle contraction should be avoided in this condition as well as stimulation applied over the scalp [25].

Intensity of stimulation needs to be considered carefully when treating patients with spinal spasticity, for example in multiple sclerosis or spinal cord injury. Stimulation may provoke disinhibited spinal reflexes, resulting in spasms in the legs, most commonly flexor spasms [28]. Needling should consider the possibility of limb movement during treatment and the practitioner may need to stay immediately by the patient to stabilize the limb and prevent movement if spasms occur.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

TENS is the application of an electrical current to the body through surface electrodes. There are similarities between electroacupuncture and TENS and the electrodes are frequently applied to acupuncture points. However their physiological effects are different, since TENS can only effectively stimulate nerve endings near the body surface. In general electroacupuncture has stronger and more long-lasting effects than TENS. Even so, TENS may have useful applications in neurological conditions for relief of pain, spasms and spasticity as well as improvement in motor and sensory function [29–31]. TENS is a useful option to provide sensory stimulation over a longer period of time and can be used by the patient as part of a home maintenance programme. Further research is required to clarify the most beneficial applications.

Scalp acupuncture

The insertion of needles into points on the Governor Vessel channel as it runs over the scalp is as old as acupuncture itself. However scalp acupuncture as a distinct system is a relatively new technique which emerged in China and Japan in the early 1970s. It is variously reported as being invented by Jiao Shunfa in 1971, Fang Yunpeng in 1970 and Toshikatsu Yamamoto in 1970. Jiao outlined a system based on the premise that needling points on the surface overlying an organ could produce beneficial effects on the underlying organs in the same way as needling mu points could benefit the associated organ. He extended this thinking to disorders of the brain and incorporated modern awareness of the functional divisions of the cerebral cortex to devise a system of stimulating the scalp to influence the brain [32].

Jiao’s system seems to have some logic to it – needling over the sensory homunculus to influence sensation and over the motor homunculus to influence movement. The system is reported to be particularly useful for neurological conditions such as stroke and Parkinson’s disease, with benefits noted for motor, sensory and speech problems, chronic muscle spasm, balance problems and tremor (see Figures 7.1 and 7.2 in Chapter 7).

Yamamoto’s system, called Yamamoto New Scalp Acupuncture, involves the needling of various points on the scalp according to zones which are reported to influence different parts of the body. It is based on a combination of Chinese medicine, Five Phases principles and Yamamoto’s microsystem theory. The important ‘brain’ points are located either side of the midline just inside the frontal hairline [33]. Yamamomoto’s system is reported to be useful for musculoskeletal and neurological conditions but has not been subjected to rigorous research protocols.

Practical application of Jiao’s system

The hair needs to be parted and skin sterilized with a solution of 2.5% iodine and 75% alcohol. The use of needles up to 7 cm in length is described, with insertion just under the skin of the scalp into the space between the epicranial aponeurosis and the periosteum. However Western practitioners usually use three or four short needles inserted obliquely along the line (see Figure 6.2 in Chapter 6). Needles may be stimulated manually. However, electroacupuncture is commonly applied, usually to each end of the line being stimulated. A frequency of 100–200 Hz is usually used, although some report using lower frequencies. Treatment lasts 20–40 minutes. Some people find scalp acupuncture to be a strong stimulation. However many experience a general warmth, tingling, pins and needles or buzzing sensation and find it relaxing. Sometimes general warmth is also felt in the body part being targeted [34].

Contraindications to scalp acupuncture

Scalp acupuncture should not be applied in the immediate acute phase after stroke until cerebral bleeding has stopped. Otherwise contraindications and precautions are the same as for manual and electroacupuncture. One short paper detailed the development of angina in two cases involving scalp acupuncture with electrostimulation provided to the highest tolerance [35]. Less intense stimulation is recommended.

Research

Anecdotal reports from China indicate miraculous results for scalp acupuncture in neurological conditions. Indeed, there are many trials from China reporting benefits from scalp acupuncture in a range of conditions such as stroke and cerebral palsy. However, virtually no rigorous research has been conducted in the West. Some trials have combined body acupuncture with scalp acupuncture but failed to indicate significant benefits for the acupuncture group compared to control group [36]. Rapson et al. [37] reported a substantial reduction in neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury following electroacupuncture at 1 Hz for 30 minutes to a number of Governor Vessel points on the scalp. This was a retrospective review of cases and represented usual clinical practice.

Clinical reasoning

It is impossible to escape the medical diagnosis and all the associated information available in the Western system. This is all useful to the acupuncture practitioner, supporting the choices we make and allowing us to estimate progress accurately. Refer back to Table 5.1 in Chapter 5 to remind yourself of the options. To return to our definition of clinical reasoning:

The Eastern way

Chinese medicine provides a particularly attractive model for holistic health care. It sees health and well-being as a state of balance between a person and every aspect of that person’s context. This indicates primarily a respectful and caring relationship with the natural environment and a lifestyle appropriate to the exigencies of natural forces and climates. It can also be extrapolated to include relationships between the body’s constitution and the way we work and play, where we live, what we eat, how we modulate our relationships with others and so on. The interdependence of mind and body goes without saying in such a comprehensive view of health. Illness is not usually an arbitrary and unlucky event but an expression of a lack of balance, and as such it is up to the individual to take care of their lifestyle to keep their health [38].

General application of TCM ideas and techniques

The two types of stagnation may be manifest in the superficial layers of the body, and both will respond to acupuncture treatment. There is a TCM saying: ‘The Blood nourishes the Qi and the Qi leads the Blood’. Qi is more Yang than Blood, which tends to be Yin. If the predominant symptom is pain it is relatively easy to distinguish between them; the main points are given in Table 12.1.

| Qi stagnation | Blood stagnation |

|---|---|

| Dull pain | Sharp, strong |

| Less severe | Severe pain |

| Mobile | Fixed |

| Palpable changes less likely | Clearly palpable by therapist, dry, scaly skin. Possible varicosities |

| Patient vague about location | Patient indicates painful point(s) clearly |

| Affected by stress or emotion | Unaffected |

| Improves with gentle massage | No immediate improvement with light massage but deep, invigorating massage may help in treatment |

| Responds to acupuncture | Responds to acupuncture |

| Distal acupuncture points are the most important | Fixed local points are more effective; these may include Ah Shi and Extra points |

| Overall regulation of body energy required | Does not affect internal functions |

The acupuncture points generally recommended for moving stagnation of the blood are listed in Table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Blood stagnation points

| Upper body | LI 11, LI 4, LU 7, LU 5 |

| Lower body | ST 36, ST 41, SP 10, SP 6 |

Moving cupping

This type of cupping can be applied where there is sufficient muscle for the connective tissues to be mobilized in this way. This may be over the scapula, on the back (Figure 12.3), on the thighs or, even, if the cup is small enough, over the facial muscles in the case of facial paralysis. It should not be used if the patient is physically frail or weak and never over open or infected skin.

Bell’s palsy with all the classic symptoms can also be treated by ‘flash’ cupping, where the small cups remain in contact for less than 30 seconds. Plastic vacuum cups may be used for this. The short duration is enough to stimulate the Qi and Blood but not enough to drain [39].

Gua Sha

Gua Sha is another Chinese technique for dealing with stagnation of the circulation. It is quite similar to an old-fashioned physiotherapeutic technique known as connective tissue massage [40].

It is also similar to cupping in that it aims to produce a deliberate increase in superficial circulation, bringing blood visibly to the surface in a red heat rash (Figure 12.4).

This is done in order to bring the Pathogenic Heat and Wind to the surface. ‘Gua’ means to scrape or scratch and ‘Sha’ translates as cholera, heat, skin rash [41]. Gu Sha is thought to mobilize the Wei Qi in the tissues.

Gua Sha is performed with a smooth-surfaced instrument, traditionally a porcelain Chinese soup spoon (Figure 12.5).

Making sense of it

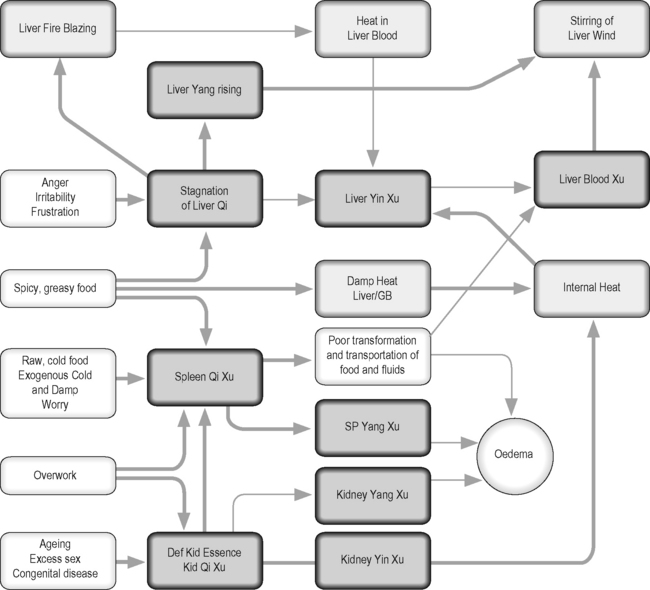

Figure 12.6 offers an overview of the links between the major syndromes involved in the treatment of neurological conditions.

[1] White A. Western medical acupuncture: a definition. Acupunct Med. 2009;27(1):33-35.

[2] Jellinger K.A. Principles and application of acupuncture in neurology. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 2000;150(13–14):278-285.

[3] MacPherson H., Thomas K., Walters S., et al. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ. 2001;323:486-487.

[4] White A., Hayhoe S., Hart A., et al. Adverse events following acupuncture:prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001;323:485-486.

[5] Peuker E., Cummings M. Anatomy for the acupuncturist – facts and fiction. 2. The chest, abdomen, and back. Acupuncture Med. 2003;21(3):72-79.

[6] Birch S., Hesselink J.K., Jonkman F.A., et al. Clinical research on acupuncture. Part 1. What have reviews of the efficacy and safety of acupuncture told us so far. Journal Of Alternative And Complementary Medicine (New York, NY). 2004;10(3):468-480.

[7] Odsberg A., Schill U., Haker E. Acupuncture treatment: side effects and complications reported by Swedish physiotherapists. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:17-20.

[8] Oleson T.D., Kroening R.J., Bresler D.E. An experimental evaluation of auricular diagnosis: the somatotopic mapping of musculoskeletal pain at ear acupuncture points. Pain. 1980;8:217-229.

[9] Nogier P.M.F., Nogier R. The Man in the Ear. Sainte-Ruffine: Maisonneuve, 1985.

[10] Frank B.L., Soliman N.E. Atlas of Auricular Therapy and Auricular Medicine. Richardson, TX: Integrated Medicine Seminars, 2000.

[11] Frank B., Soliman N. Zero point: A critical assessment through advanced auricular therapy. Journal of the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists. 2001:61-65.

[12] Hecker H.-U., Steveling A., Peuker E., et al. Color Atlas of Acupuncture. Stuttgart: Thieme, 2000.

[13] Bourdiol R.J. Elements of Auriculotherapy. Moulin-le-Metz, France: Maisonneuve Editions, 1982.

[14] Oleson T., Kroening R. A new nomenclature for identifying Chinese and Nogier acupuncture points. Am J Acupuncture. 1983;12:325-344.

[15] Simmons M., Oleson T. Auricular electrical stimulation and dental pain threshold. Anesth Prog. 1993;40:14-19.

[16] Smith M.O., Khan I. An acupuncture programme for the treatment of drug addicted persons. Bull Narc. 1988;XL:35-41.

[17] Szopinski J.Z., Lukasiewicz S., Lochner G.P., et al. Influence of general anesthesia and surgical intervention on the parameters of auricular organ projection areas. Medical Acupuncture. 2003;14(2):40-42.

[18] Chen H.Y., Shi Y., Ng C.S., et al. Auricular acupuncture treatment for insomnia: a systematic review. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, NY). 2007;13(6):669-676.

[19] Dorsher P.T., Fleckenstein J. Trigger points and classical acupuncture points: part 3: relationships of myofascial referred pain patterns to acupuncture meridians. Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Akupunktur. 2009;52(1):9-14.

[20] Baldry P.E. Acupuncture, Trigger Points and Musculoskeletal Pain, 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

[21] Edwards J., Knowles N. Superficial dry needling and active stretching in the treatment of myofascial pain. A randomised controlled trial. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2003;21(3):80-86.

[22] Gunn C. Treating Myofascial Pain. Seattle: University of Washington, 1989.

[23] Gunn C.C. Treatment and Needle Technique. Treating myofascial pain. Seattle, USA: University of Washington Medical School, 1989;37-44.

[24] Chou L.W., Hsieh Y.L., Kao M.J., et al. Remote influences of acupuncture on the pain intensity and the amplitude changes of endplate noise in the myofascial trigger point of the upper trapezius muscle. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(6):905-912.

[25] Mayor D.F. Electroacupuncture: a practical manual and resource. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007.

[26] White A., Cummings M., Filshie J. An introduction to western medical acupuncture. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

[27] Conforto A.B., Cohen L.G., dos Santos R.L., et al. Effects of somatosensory stimulation on motor function in chronic cortico-subcortical strokes. J Neurol. 2007;254(3):333-339.

[28] Donnellan C.P., Shanley J. Comparison of the effect of two types of acupuncture on quality of life in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: a preliminary single-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(3):195-205.

[29] Miller L., Mattison P., Paul L., et al. The effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) on spasticity in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2007;13(4):527-533.

[30] Ng S.S.M., Hui-Chan C.W.Y. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation combined with task-related training improves lower limb functions in subjects with chronic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2953-2959.

[31] Yan T., Hui-Chan C.W. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation on acupuncture points improves muscle function in subjects after acute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(5):312-316.

[32] Jiao S. Scalp Acupuncture and Clinical Cases. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1997.

[33] Feely R.A. Yamamoto new scalp acupuncture: principles and practice. New York: Thieme, 2006.

[34] Yau P.S. Scalp-Needling Therapy. Beijing: Medicine & Health Publishing, 1990.

[35] Li C.D., Jiang Z.Y. Angina pectoris induced by electric scalp acupuncture: report on two cases. International Journal of Clinical Acupuncture. 1998;9(1):53-54.

[36] Hopwood V., Lewith G., Prescott P., et al. Evaluating the efficacy of acupuncture in defined aspects of stroke recovery: a randomised, placebo controlled single blind study. J Neurol. 2008;255(6):858-866.

[37] Rapson L.M., Wells N., Pepper J., et al. Acupuncture as a promising treatment for below-level central neuropathic pain: a retrospective study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26(1):21-26.

[38] Lyttelton J. Of molecules, meridians and medicine: the feminist influence – putting the yin back into health care. Am J Acupunct. 1992;20(3):237-243.

[39] Chirali I.Z. Empty (flash) cupping. Traditional Chinese Medicine; Cupping Therapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007;87.

[40] Brattberg G. Connective tissue massage in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Eur J Pain. 1999;3(3):235-244.

[41] Nielsen A. Gua Sha, a traditional technique for modern practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

[42] NHS Evid CAM Newsletter. http://www.library.nhs.uk/CAM/NHSLibrary, 2009. Available online at: