Chapter 31 Puberty and Disorders of Pubertal development

This part of Essentials (Chapters 31 through 36) deals with the normal and abnormal hormonal influences on the female reproductive system. The sequence of events is an excellent example of the “Life-Course Perspective” for women’s health and health care introduced in Chapter 1. This series of events begins with endocrine changes in the fetus, the neonate, and then into childhood and pubertal development, then is followed by the early reproductive years, continuing on through the female climacteric, over the life course of a woman’s reproductive years. This section of the book concludes with a chapter on other common disorders that are influenced by normal and abnormal hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle.

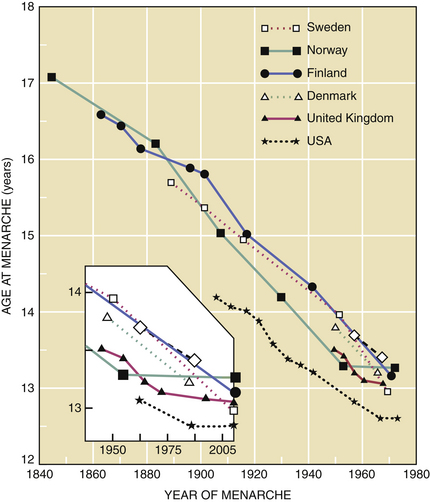

In the United States and Western Europe, a decrease in the age of menarche (age at first menses) was noted between 1840 and 1970. This trend has plateaued in the past 30 years (Figure 31-1). Presently, the mean age of menarche is about 12.4 years in the United States.

Endocrinologic Changes of Puberty

Endocrinologic Changes of Puberty

FETAL AND NEWBORN PERIOD

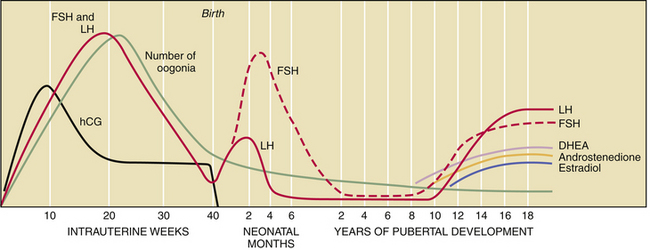

The fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is capable of producing adult levels of gonadotropins and sex steroids. By 20 weeks’ gestation, levels of gonadotropins—follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)—rise dramatically in both male and female fetuses (Figure 31-2). The female fetus acquires the lifetime peak number of oocytes by mid-gestation, and she experiences a brief period of follicular maturation and sex steroid production in response to elevated gonadotropin levels in utero. This transient increase in serum estradiol (a sex steroid) acts on the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary unit, resulting in a reduction of gonadotropin secretion (negative feedback effect), which in turn reduces estradiol production. This indicates that the inhibitory effect of sex steroids on gonadotropin release is operative before birth.

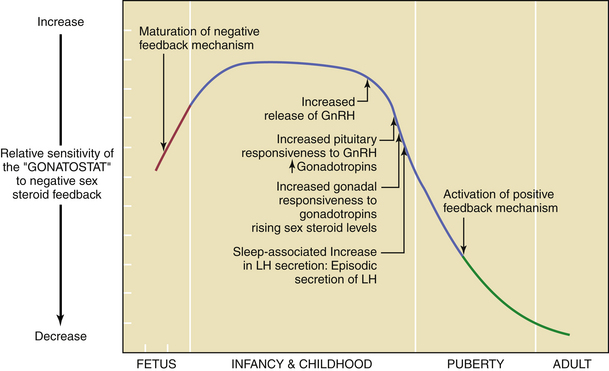

PUBERTAL ONSET

By about the 11th year of life, there is a gradual loss of sensitivity by the gonadostat to the negative feedback of sex steroids (Figure 31-3). As a consequence of this reduced negative feedback effect, GnRH pulses (with their mirroring pulses of FSH and LH) increase in amplitude and frequency. The factors that reduce the sensitivity of the gonadostat are incompletely understood. Some studies indicate that a rise in the concentration of leptin, a hormone produced by adipocytes (fat cells) that mediates appetite satiety, precedes and is necessary for this change. This, in turn, supports the connection between minimum weight or total body fat and the onset of puberty. A further decrease in sensitivity of the gonadostat, combined with the loss of intrinsic central nervous system inhibition of hypothalamic GnRH release, is heralded by sleep-associated increases in GnRH secretion. This nocturnal-dominant pattern gradually shifts into an adult-type secretory pattern, with GnRH pulses occurring every 90 to 120 minutes throughout the 24-hour day.

Somatic Changes of Puberty

Somatic Changes of Puberty

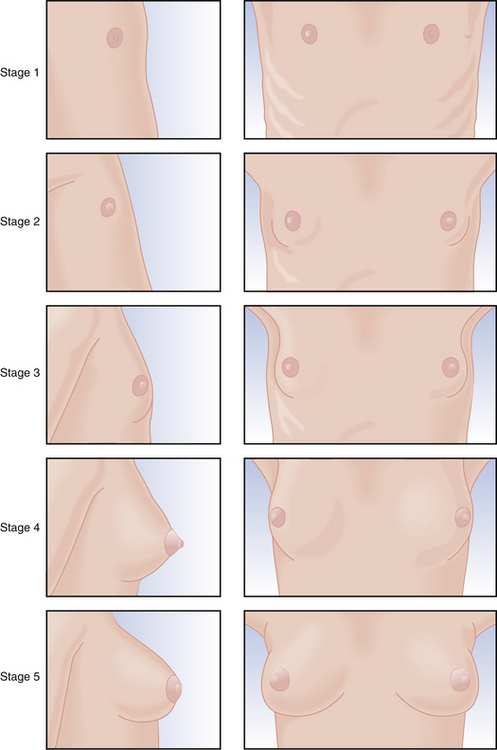

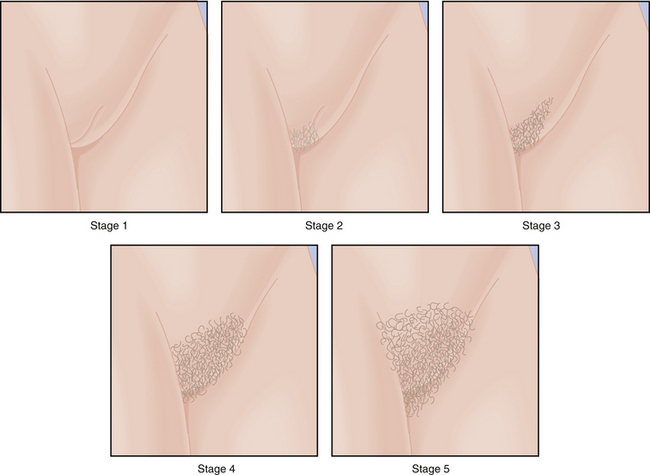

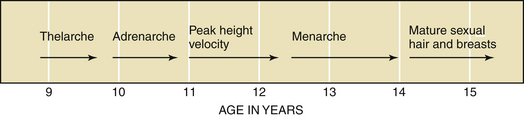

Physical changes of puberty involve the development of secondary sexual characteristics and the acceleration of linear growth (gain in height). The classification of breast and pubic hair development by Marshall and Tanner is employed for descriptive and diagnostic purposes (Figures 31-4 and 31-5).

STAGES OF PUBERTAL DEVELOPMENT

The first physical sign of puberty is usually breast budding (thelarche), followed by the appearance of pubic or axillary hair (pubarche or adrenarche). Unilateral breast development is not uncommon in early puberty and may last up to 6 months before the development of the contralateral breast. Maximal growth or peak height velocity is usually the next stage, followed by menarche (the onset of menstrual periods). The final somatic changes are the appearance of adult pubic hair distribution and adult-type breasts. In about 15% of normal girls, the development of pubic hair occurs before breast development. The sequence of pubertal changes generally occurs over a period of 4.5 years, with a normal range of 1.5 to 6 years (Figure 31-6).

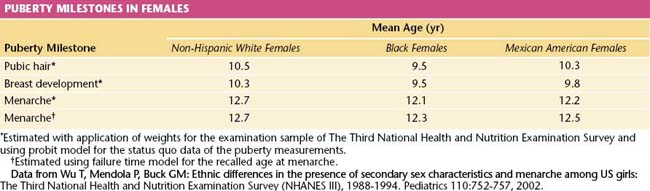

Race plays a role in determining the age of the onset of puberty. African American girls begin puberty earlier than other racial groups (on average between the ages of 8 and 9 years), followed by Mexican Americans and whites (Table 31-1). In African American girls, thelarche and adrenarche can occur as early as 6 years of age, whereas in whites, they can occur as early 7 years of age.

Precocious Puberty

Precocious Puberty

The early development of secondary sexual characteristics may promote psychosocial problems for the child and should be carefully addressed. Typically, these girls are taller than their peers as children but ultimately are shorter as adults owing to the premature fusion of the long-bone epiphyses. A classification system for female precocious puberty is shown in Box 31-1.

BOX 31-1 Classification of Female Precocious Puberty

Data from Brenner PF: Precocious puberty in the female. In Mishell DR Jr, Davajan V (eds): Infertility, Contraception and Reproductive Endocrinology, 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA, Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1991, p 349.

Investigations for females with precocious puberty are shown in Box 31-2.

BOX 31-2 Laboratory Tests Used Selectively to Evaluate Female Precocious Puberty

Radiologic

TREATMENT OF TRUE ISOSEXUAL PRECOCIOUS PUBERTY

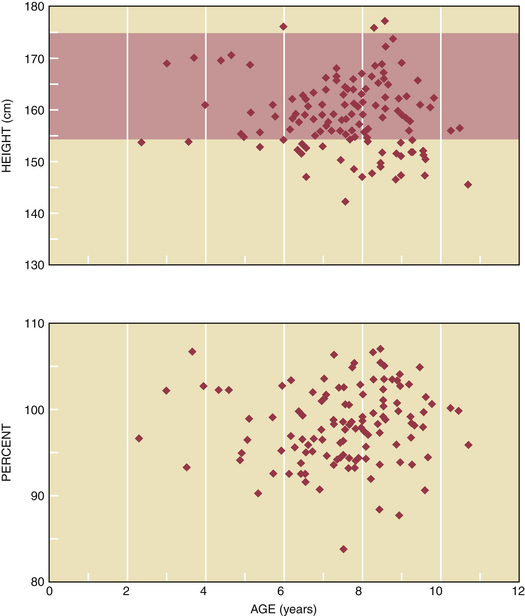

The final adult stature of girls with GnRH-dependent causes of precocious puberty is strongly influenced by their chronologic age at diagnosis and initiation of treatment. When GnRH agonist treatment is initiated before the chronologic age of 6 years, the final adult height is increased by 2% to 4% (Figure 31-7). In contrast, the final adult height is usually not affected when the chronologic age at diagnosis and treatment is greater than 6 years of age.

Delayed Puberty

Delayed Puberty

Although there is a wide variation in normal pubertal development, most girls in the United States begin pubertal maturation by the age of 13 years. Failure to undergo thelarche by age 14 years requires evaluation. A physiologic delay in the onset of puberty occurs in only 10% of girls with delayed puberty, and exclusion of other diagnoses is necessary. Physiologic delays in puberty tend to be familial. A careful history must be taken, with special attention to the patient’s past general health, height, dietary habits, and exercise patterns. Details about the pubertal development of the patient’s siblings and parents should be obtained. Box 31-3 lists tests that should be performed to evaluate girls with delayed puberty.

In general, the causes of delayed onset of puberty can be subdivided into two categories: hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. Disorders resulting in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism that may cause primary or secondary amenorrhea are discussed in Chapter 32. Of note, anorexia nervosa, which can result in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and delayed puberty, can affect 0.5% to 1.0% of young women. It is important to recognize this disorder in the evaluation of these patients. Chromosomal abnormalities or injury to the ovaries by surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation may cause hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. When the patient’s abnormal karyotype includes the presence of a Y chromosome, gonadectomy is recommended to prevent potential malignant neoplastic transformation.

Adolescents who present with permanent hypoestrogenism require estrogen therapy as described in Chapter 32, to complete the development of secondary sexual characteristics. Hormone therapy with estrogen plus a progestin or with a low-dose oral contraceptive after establishment of secondary sexual characteristics is required to avoid menopausal symptoms and to prevent osteoporosis. To further maximize bone mineral accretion, 1500 mg of elemental calcium and 400 mg of vitamin D daily are recommended. This should be combined with regular weight-bearing exercises.

Carr B., Blackwell R., Azziz R. Disorders of puberty and amenorrhea. In Carr B., Blackwell R., Azziz R., editors: Essential Reproductive Medicine, 1st ed, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Feldman Witchel S., Plant T.M. Puberty: Gonadarche and adrenarche. In Strauss J.F., Barbieri R.L., editors: Yen and Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, 5th ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2004.

Jaffe R.B. Disorders of sexual development. In Strauss J.F., Barbieri R.L., editors: Yen and Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, 5th ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2004.

Pigneur B., Trivin C., Brauner R. Idiopathic central precocious puberty in 28 boys. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14:CR10-14.

Speroff L., Fritz M. Abnormal puberty and growth problems. In Speroff L., Fritz M., editors: Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, 7th ed, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Speroff L., Fritz M. Normal and abnormal sexual development. In Speroff L., Fritz M., editors: Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, 7th ed, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 2005.