Chapter 20 Psychosomatic Illness

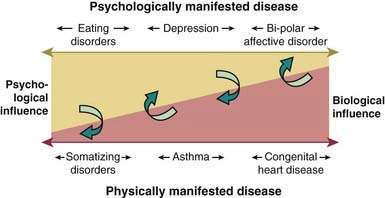

Psychosomatic medicine deals with the relation between physiologic and psychologic factors in the cause or maintenance of disease. Physical illnesses have accompanying emotional symptoms, and psychiatric illnesses commonly have associated somatic or physical symptoms. It is important for health care providers to avoid the dichotomy of approaching illness using a medical model in which diseases are considered either organic or psychologically based. A biobehavioral continuum of disease characterizes illness as occurring across a spectrum ranging from a biologic etiology on one end to predominantly a psychosocial etiology on the other (Fig. 20-1). Using the biopsychosocial approach, biologic, psychologic, social, and developmental realms are integrated into an understanding of an individual patient’s presentation.

Figure 20-1 Biobehavioral continuum of disease.

(From Wood BL: Physically manifested illness in children and adolescents: a biobehavioral family approach, Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 10:543–562, 2001.)

The DSM-IV-TR category of somatoform disorders includes Somatization Disorder, Conversion Disorder, and Pain Disorders Associated with Both Psychological Factors and a General Medical Condition (Tables 20-1 to 20-4). Somatoform Disorder Not Otherwise Specified includes presentations with disabling somatic symptoms that do not meet the full DSM-IV-TR criteria for any of the aforementioned disorders. Hypochondriasis and Body Dysmorphic Disorder occur rarely in childhood.

Table 20-1 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR SOMATIZATION DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 490.

Table 20-2 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR UNDIFFERENTIATED SOMATOFORM DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 492.

Table 20-3 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR CONVERSION DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 498.

Table 20-4 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR PAIN DISORDER

Code as Follows:

307.80 Pain Disorder Associated with Psychological Factors: psychological factors are judged to have the major role in the onset, severity, exacerbation, or maintenance of the pain. (If a general medical condition is present, it does not have a major role in the onset, severity, exacerbation, or maintenance of the pain.) This type of Pain Disorder is not diagnosed if criteria are also met for Somatization Disorder.

Specify If:

Specify If:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association, p 503.

Risk Factors

Assessment

Medical

The medical evaluation of suspected psychosomatic illness should include an assessment of biologic, psychologic, social, and developmental realms both separately and in relation to each other. A comprehensive medical work-up to rule out serious physical illness must be carefully balanced with efforts to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful tests and procedures. Although the likelihood of finding physical illness in patients with somatoform disorders at initial diagnosis is less than 10%, certain physical illnesses should be considered, such as Lyme disease (Chapter 214), systemic lupus erythematosus (Chapter 152), multiple sclerosis (Chapter 593), infectious mononucleosis (Chapter 246), irritable bowel syndrome (Chapter 334), migraine (Chapter 588.1), and seizure disorders (Chapter 586).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Conversion disorder denotes the loss or alteration of physical functioning without demonstrable organic pathology (see Table 20-3). It occurs in adolescence or adulthood, although numerous childhood cases have been reported. Conversion reactions usually start suddenly, can often be traced to a precipitating environmental event, and can end abruptly after a short duration. Voluntary musculature and organs of special sense are the most common target sites for expressions of conversion reactions. Such reactions can take the form of blindness, paralysis, diplopia, and postural or gait disturbances. Pseudoseizures are a common manifestation of a conversion disorder.

In somatoform pain disorder, pain is the primary physical symptom (see Table 20-4). These disorders are characterized by reoccurrence. Prevalence studies suggest that 11% of boys and 15% of girls have ongoing somatic symptoms. Recurrent abdominal pain accounts for 2-4% of all pediatric visits and headaches for an additional 1-2%. Most of these children do not have any positive clinical findings.

Additional diagnoses to consider include malingering and factitious disorders. Malingering, which is very rare in the pediatric setting, can be distinguished from somatoform disorders by looking at the motivation for the symptoms. Persons who are malingering will intentionally produce or exaggerate physical symptoms to receive some external reward. Persons with factitious disorder on the other hand are not motivated by external rewards but instead have an intrapsychic need to remain in the sick role (Table 20-5). Factitious disorders cause somatic and/or psychologic symptoms that are deliberately fabricated in the absence of any potential gain to the patient, other than the benefit of assuming the sick role (see Table 20-5). Munchausen syndrome is an example of a chronic factitious disorder typically seen in adults who persist in seeking medical treatments, including surgery, despite the lack of any real disease. Factitious disorder by proxy is a variant in which parents induce physical symptoms in their children in order to assume the sick role by proxy (Chapter 37.2). In such cases infants and young children can present with fractures, poisonings, persistent episodes of apnea, and other unusual ailments. It is considered a form of child abuse, which can be lethal, and must be reported to the appropriate authorities.

Table 20-5 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF FACTITIOUS DISORDER

CODE BASED ON TYPE

From Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, Elsevier/Saunders, p 84.

Treatment

It is generally believed that effective treatment needs to incorporate a number of different treatment modalities to target the factors that are believed to be associated with the development of somatization. Given the “diagnostic uncertainty” in these disorders, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended, including a stepwise plan for developing an integrated medical and psychiatric treatment strategy to somatoform disorders (Table 20-6).

Table 20-6 STEPWISE APPROACH TO DEVELOPING AN INTEGRATED MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC TREATMENT APPROACH TO SOMATOFORM DISORDERS

COMPLETE MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC ASSESSMENTS

CONVENE AN INFORMING CONFERENCE WITH THE FAMILY

IMPLEMENT TREATMENT INTERVENTIONS IN BOTH MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC DOMAINS

Modified from DeMaso DR, Beasley PJ; The somatoform disorders. In Klykylo WM, Kay JL, Rube DM, editors: Clinical child psychiatry, ed 2, London, 2005, John Wiley & Sons, p 481, Table 26.3.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Beasley PJ, DeMaso DR. Conversion and pain disorders. In: Zaoutis LB, Chang VW, editors. Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007:1051-1055.

Campo J, Shafer S, Lucas A, et al. Managing pediatric mental disorders in primary care: a stepped collaborative care model. J Am Psych Nurses Assoc. 2005;11(5):1-7.

Dahlquist L, Switkin M. Chronic and recurrent pain. In: Roberts MC, editor. Handbook of pediatric psychology. ed 3. New York: Guilford; 2003:198-215.

DeMaso DR, Martini DR, Cahen LA, et al. Work Group on Quality Issues: Practice parameter for the psychiatric assessment and management of physically ill children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. 2009;48:213-233.

DeMaso DR, Beasley PJ. The somatoform disorders. In: Klykylo WM, Kay JL, editors. Clinical child psychiatry. London: John Wiley & Sons; 2005:471-486.

Shaw RJ, Dayal S, Hartman JK, et al. Factitious disorder by proxy: a pediatric falsification condition. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 2008;16:215-224.

Spratt EG, DeMaso DR. Somatoform disorder, somatization (website). http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/918628-overview. Accessed February 12, 2010

Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR. Mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents. In: Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR, editors. Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2006.

Wood BL. Physically manifested illness in children and adolescents: a biobehavioral family approach. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;10:543-562.