Psychosocial issues in breast cancer

Delay in presentation

Despite efforts to increase awareness, many women in the UK present late with their breast cancer; this delay can be due to patient or provider factors. Patient delay refers to the interval between first detection of symptoms and first medical consultation. The period that most authors accept as prolonged delay is 12 weeks or more,1 although others regard patient delay as 4 weeks or more.2 Provider or system delay is usually taken to be the interval between first presentation to the GP and initial treatment, and is not easy to define. Some of the reasons for patient delay can be ignorance of the symptoms, or fears about breast cancer and its associated treatments.

Unfortunately, delay of greater than 3 months is associated with worse outcomes. In the UK it has been shown to contribute to the difference in survival between rich and poor3 and ethnic groups, especially Black African women.4 Also, older women who have lower levels of knowledge about the signs and symptoms of breast cancer are more likely than younger women to present late. In a survey of 712 older (67–73 years) British women, 50% believed their lifetime risk of developing breast cancer was 1 in 100 and 75% were not aware that age was a risk factor.5 In an attempt to improve breast awareness, Linsell et al. conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 867 women attending for their final routine appointment on the UK NHS Breast Screening Programme.6 Women were randomised to receive a scripted 10- minute interaction with a radiographer plus a booklet that conveyed key breast awareness messages, the booklet alone or usual care. The primary outcome was the proportion of women achieving breast cancer awareness at 1 month. Results from this RCT did show an increased awareness in the intervention group compared with usual care at 1 month (32.8% vs. 4.1%), and the booklet versus usual care (12.7% vs. 4.1%), which was largely maintained at 12 months. Whether knowledge translates into a change in behaviour is yet to be determined. A systematic review of the efficacy of interventions to promote cancer awareness and early presentation reveals some evidence that interventions delivered at an individual level can promote cancer awareness in the short term, but insufficient evidence that these promote early presentation with cancer symptoms.7 Individuals’ behaviours are not governed by a single set of attitudes and can change over time, therefore predicting which factors determine change is involved and complex.

Psychosocial issues with breast cancer surgery

Although surgeons perform breast-conserving surgery (BCS) wherever possible, this does not always translate into measurable reductions in psychological morbidity. Some have suggested that psychological morbidity could be prevented if only women were allowed to choose their preferred surgical treatments. Although the proponents of more consumerist approaches strongly assert the putative benefits of active participation in treatment decision-making, these benefits are not well supported by firm data. In one study, the decision-making preferences of 150 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer were established and compared with those of 200 women with benign breast disease. The majority of women with breast cancer preferred a more passive role, whereas the majority of the benign disease group wished for a more collaborative role.8

Data from the USA examined decision-making in 1884 women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive breast cancer. Results showed that although only 11.5% had clinical contraindications to BCS, 30% had mastectomy as their initial surgical treatment. The majority of the women (41%) reported that they had been the primary decision-maker, 37% felt that the decision was shared with the surgeon and 22% felt that the decision had been made by their surgeon.9 Intriguingly, the greater the patient involvement in decision-making the more likely that mastectomy was the preferred surgery. After adjusting for clinical and demographic variables, significant correlations were found. Only 5.8% of women whose surgeon made the decision had a mastectomy compared with 16.8% of the women who shared decision-making and 27% of those who made the decision themselves (P = 0.003). The primary reason for a mastectomy preference was fear about recurrence. Although 80% of women expressed a high degree of confidence about their decisions, fewer than 50% were able to answer correctly a true/false question about the lack of a survival difference between mastectomy and BCS.

Effects of type of surgery

Many have asserted that the type of surgery makes a difference to patients’ quality of life (QoL). However, except for differences in perception of body image, the literature comparing the other psychosocial sequelae of BCS with mastectomy is ambiguous and shows a lack of substantial benefits.10–12 Few have examined QoL prospectively beyond a 2-year period, yet approximately 80% of women with breast cancer survive ≥ 5 years.13 Engle et al.14 measured long-term QoL in women (n = 990) treated with BCS or mastectomy at regular intervals over 5 years. The cross-sectional data showed that mastectomy patients had significantly (P < 0.01) lower satisfaction with body image, role and sexual functioning scores, and their lives were more disrupted than BCS patients. Another study showed that at 5 years women who had BCS had a significant increase in overall QoL compared with those who had a mastectomy.15 Surprising differences were found by Collins et al. examining QoL in women (n = 549) who had BCS, mastectomy or mastectomy plus reconstruction.16 The researchers adjusted the analysis to take account of the severity of surgical side-effects by type of operation. In the model without surgical side-effect severity, women who underwent mastectomy plus reconstruction reported poorer body image than those who had BCS at all time points except the last (T4: 2 years post op). When they adjusted for surgical side-effect severity, body image scores did not differ significantly from patients with BCS. Also, women who had mastectomy alone had a better body image at T2 (6 months) than those who had reconstruction (P = 0.011). The authors explained that dissatisfaction with body image can be explained in part by patients’ experience of surgical side-effects, including wound infections. However, the severity of the side-effects did not substantially weaken the effects of an elevated depressed mood on patients’ body image problems.

Impact of axillary surgery on quality of life

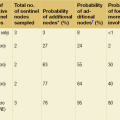

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is now established as an accurate, minimally invasive means of providing regional staging for primary breast cancer, and the standard of care for patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer.17 In the UK ALMANAC (Axillary Lymphatic Mapping Against Nodal Axillary Clearance) trial of 1031 patients, data showed that women who received standard axillary treatment recovered more slowly than those in the SLNB group (P < 0.01).18 The ALMANAC trial showed that the benefits of sentinel node biopsy are not only reduction of unnecessary resection of the axilla, but also a marked reduction in unwanted sequelae such as arm morbidity, thus permitting a better quality of life, without sacrificing any staging accuracy. However, 25% of the SLNB group required further axillary surgery or radiotherapy to the axilla because of spread of disease. Additional surgery is normally conducted 2 weeks later and this two-stage procedure has advantages and disadvantages. The latter include the psychological and physical stress associated with a second operation; conversely, the delay could be viewed as a benefit by some, giving time to adjust to the knowledge that their breast cancer has spread. Recently some units are able to offer intraoperative SLNB analysis, which allows immediate progression to axillary clearance in patients found to have positive nodes. However, there is still debate amongst clinicians on the accuracy of intraoperative analysis,19,20 but findings from women who had and had not experienced this diagnostic technique revealed a positive inclination towards the one-step axillary surgery. The advantages included: knowing the result straight away, less anaesthesia, fewer days in hospital and consequently more cost-effectiveness for the NHS.21

Ductal carcinoma in situ

Women given the diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), be it low, moderate or high grade, can be left wondering whether or not they have breast cancer. Some describe it as ‘a very early form of breast cancer’22 or pre-cancerous condition. Most often it is found through mammographic screening and the incidence is increasing. Although mortality risk is low, treatments are similar to that demanded of invasive breast cancer (surgery, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy) and women are left confused. The psychological and QoL impacts of having a label of DCIS and how it affected women’s lives have been subject to review.23 Studies show that although those with low/intermediate-grade DCIS have an excellent prognosis and normal life expectancy, many women experience substantial psychological distress. Cross-sectional studies have compared psychosocial outcomes of women with DCIS with those with early invasive breast cancer (EBC).24,25 Findings suggest DCIS patients have better physical health, sex life and social functioning than women with invasive breast cancer. However, despite the relatively good prognosis, DCIS patients held perceptions about the risk of recurrence and dying comparable to women with EBC. Other research showed that women had inaccurate perceptions about their risk of invasive disease and spread of DCIS to other parts of their body that changed little across an 18-month period; these perceptions were strongly related to distress.26

Lauszier et al. reported similar levels of psychological distress in women with DCIS and those with invasive disease who had a worse prognosis.27 So although women with DCIS reported significantly better physical health, it did not offset the psychological distress felt of having a cancer diagnosis. This finding is supported from results of a UK-based study with 50 women with DCIS, whose QoL, psychological functioning and body image were measured at three time points (baseline, 6 and 9 months). The results provide a valuable insight of emotional distress during the first year post-diagnosis, with some women experiencing significant levels of distress both in the short and long term.28 Previous DCIS research has proposed that some of the influencing factors for this distress are confusion about the diagnosis and prognosis, together with inaccurate risk perceptions.

There remains considerable controversy about the natural history of low-grade DCIS and it is now commonly diagnosed by routine breast cancer screening. The diagnosis and treatment of a condition that may not cause problems during the patient’s lifetime is considered by some to be both overdiagnosis and overtreatment.29 There are few conclusive data demonstrating that low-grade DCIS commonly develops into invasive cancer, prompting some to question the use of the word carcinoma in the diagnosis. Conducting randomised trials to determine whether or not active surveillance or giving endocrine therapy is as safe an option as immediate surgery is important but fraught with difficulty. Outcomes of both the safety and psychosocial sequelae of hormone therapy (IBIS II) are awaited. Clinical trials comparing surgery with active monitoring or hormone therapy for low-grade DCIS are urgently required.

Hormone therapy

Studies comparing clinician-reported (via case report forms in trials) and patient-reported (via validated questionnaires and interviews) quality of life rather than life-threatening side effects show little concordance.30–33 Apart from this inaccurate reporting, severe and/or untreated side-effects can lead to discontinuation of therapy or non-adherence in between 25% and 55% of patients.34,35 Ameliorative interventions are consequently an important and neglected area of research. In the section below we present an overview of some of the evidence for various interventions aimed at the primary side-effects: vasomotor complaints, gynaecological/ sexual issues and musculoskeletal problems, especially arthralgia.

Vasomotor problems

Hot flushes and drenching night sweats are some of the most commonly reported problems (30–45%) associated with all hormone treatments.34,35 Not only are they extremely unpleasant but they interfere with sleep and impact on numerous other activities of daily living and quality of life. Mechanisms are complex but are probably oestrogen withdrawal rather than related to absolute levels of circulating oestrogen. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is of course a useful treatment for menopausal hot flushes but HRT is not appropriate for breast cancer, as shown in the HABITS trial.36 Other ameliorative interventions are shown in Table 16.1.

Table 16.1

Ameliorative interventions for side-effects

| Complementary therapies | Acupuncture, relaxation, paced breathing, yoga, t’ai chi, mindfulness, hypnosis |

| Dietary changes | Avoidance of alcohol, caffeine and spicy foods |

| Supplements and herbal remedies | Dong quai, primrose oil, red clover, Black Cohosh, Mexican yam |

| Practical advice | Dressing in layers, menopausal pyjamas and chillows, air-conditioning, fans and drinking cold water |

| SSRIs and SNRIs | e.g. venlafaxine, paroxetine |

Acupuncture

A systematic review of acupuncture in breast cancer showed that of the three RCTs employing sham acupuncture control arms, only one was favourable in reducing hot flush frequency; however, a meta-analysis has suggested a benefit overall (P = 0.05), although there was marked heterogeneity in the data.37 One study of acupuncture compared with HRT favoured HRT, another two comparing acupuncture versus venlafaxine or relaxation therapy found a small benefit for acupuncture but no differences between groups. All these studies suffer from small numbers. A more comprehensive study enrolled women who had experienced more than seven hot flushes per day for 7 consecutive days.38 Patients were randomised to acupuncture or control. Primary outcome was hot flush frequency with a wide variety of other secondary end-points. Both frequency and intensity of hot flushes were significantly reduced in the acupuncture arm (P < 0.001). There were also reductions in sleep disturbance and other somatic symptoms as measured with the Women’s Health Questionnaire (WHQ).39

Relaxation, mindfulness, yoga, hypnosis

Stress and anxiety are common features associated with the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer and appear to contribute to the frequency and intensity of symptoms.40,41 It seems a reasonable hypothesis therefore that any behavioural technique that reduces stress may help vasomotor complaints. As with acupuncture these studies often lack good controls and include only small numbers but there does appear to be some beneficial evidence in support of hypnosis,42 relaxation/paced breathing,43,44 yoga45 and group cognitive behavioural therapy.46 From a clinical point of view all these interventions have the advantages of being inexpensive, very acceptable and attractive to women, and importantly have no adverse events.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

Clinicians who are sceptical about the previously mentioned interventions are often more comfortable recommending drug therapies such as the selective serotonin or norepinephrine uptake inhibitors. Venlafaxine has been tested in numerous studies. An important double-blind placebo-controlled RCT of different doses revealed a significant reduction in hot flush scores (P < 0.001) but some side-effects, including a dry mouth, appetite loss and constipation.47 A double-blind crossover study with paroxetine showed a significant reduction in hot flushes (P < 0.001); furthermore, patients were less likely to discontinue a 10-mg dose compared with 20 mg, as the latter dose resulted in greater toxicity.48 In a double-blind crossover RCT of fluoxetine there was a 24% improvement in hot flush reduction favouring fluoxetine (P = 0.02).49 Likewise, another randomised double-blind crossover study favoured sertraline.50 This project also examined preference and demonstrated that 48% of patients preferred sertraline, 11% placebo and 41% had no preference. Anxieties still exist about the potential effects of CYP 2D6 inhibition for some patients taking tamoxifen and SSRIs, although most recent research has failed to offer compelling cause for concern. The benefits of SSRIs and SNRIs in hot flush reduction are clear, but the side-effects sometimes outweigh these and may lead to discontinuation. Research on efficacy and safety with newer antidepressants such as mirtazapine or citalopram is ongoing, and also with the anticonvulsant gabapentin, to see if they have fewer side-effects. Gabapentin produces a 35–66% reduction in hot flash score but patients prefer venlafaxine 2:1 over gabapentin. Likewise, there are several comparative trials being conducted of different treatments using reductions of vasomotor problems and patient preference as outcomes.51 Most recent research has suggested that escitalopram (Cipralex) conveys benefits without too many side-effects.52

Gynaecological/sexual problems

The AIs and SERMs create numerous gynaecological and sexual problems for patients. Discharge (5–17%) is probably higher in tamoxifen than in the AIs but vaginal dryness affects between approximately 16% and 40% of women taking anastrozole, exemestane or letrozole.33 As a consequence, previously sexually active women may experience dyspareunia (15–18%) and a loss of libido (16–45%). In extreme cases patients may develop very unpleasant and painful vulvo-vaginal atrophy. The most appropriate ameliorative intervention for dryness and dyspareunia is regular use of moisturisers such as Replens®. Lubricants alone are insufficient. For vulvo-vaginal atrophy there are suggestions from early phase trials that progesterone and testosterone creams may help.53 For clinicians worried about oestrogen in breast cancer, studies have shown that Estring® has a low systemic uptake of oestrogen.54

Musculoskeletal problems and arthralgia

Adjuvant trials of anastrozole,55 letrozole56 and exemestane57 show reports of joint pains and stiffness or arthralgia to be common (20–30%). A survey of UK clinicians reported that AI-induced arthralgia is a distinct clinical problem, with limited data on its aetiology and management.58 Arthralgic pain and stiffness can be an important reason for discontinuation of AI therapy. Unfortunately, these do not always respond to analgesia, they negatively impact on QoL and can lead to non-adherence. The mechanism remains uncertain and is certainly different from the normal aches and pains of ageing. Oestrogen deprivation, together with the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1β, tumour necrosis factor-α), is the most likely cause.59

Crew et al. conducted a small crossover study of full-body and auricular acupuncture, 30 min, twice weekly for 6 weeks on 27 women who had been taking an AI for at least 6 months and who were experiencing arthralgia.60 Using numerous validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROs), the authors reported significant improvements in worst pain (P = 0.01), pain severity (P = 0.02), functional interference (P = 0.02), functional ability (P = 0.02) and overall physical well-being (P = 0.04).

SSRIs and SNRIs

Duloxetine is an SNRI used for multiple chronic pain. Henry et al. reported a small pilot study for postmenopausal women on AIs with new or worsening pain.61 Duloxetine 30 mg daily was administered for 7 days, then increasing to 60 mg daily. The study employed many patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures, looking at quality-of-life symptoms, sleep quality, menopause and hot flushes, but the primary end-point was a 30% decrease in pain. Results showed that 21 of 29 evaluable patients reported ≥ 30% decreased pain. The authors also reported other significant improvements including the amount of interference caused by pain and improvement in hot flushes, depression and sleep. Although 78% of patients continued on treatment, it did cause fatigue, xerostomia and headache. This was a very small study but the drug seems worthy of examination in a larger RCT. In an observational study vitamin D deficiency was suggested as the cause of musculoskeletal pain62 and a double-blind placebo-controlled RCT of high-dose vitamin D seemed to improve pain reports.63

Exercise

In the past, cancer patients were usually advised to rest and avoid physical effort. However, it is now well established that excessive rest and lack of physical activity may result in severe deconditioning and reduced physical functioning. Women undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy as adjuvant treatment for breast cancer commonly experience debilitating side-effects including nausea,64 fatigue,65 weight gain66 and mood disturbances.67 These side-effects can interfere with daily activities such as self-care or return to work and exercise for patients with cancer is strongly supported by national cancer charities. A report by Macmillan suggested that patients who are receiving cancer treatments engage in two and a half hours of exercise a week.68 This advice is in line with the Department of Health guidelines that recommend two and a half hours of moderate to vigourous intensity exercise for adults each week, moderate exercise defined as swimming or a brisk walk.69 Adherence to exercise programmes is, however, a problem and the mean dropout rate from supervised exercise programmes has remained at 50% over the decades.70 However, being diagnosed with a serious illness can prompt an individual to change their lifestyle and there are media reports of individuals running half-marathons even whilst undergoing treatments for breast cancer.71

Whilst these are uplifting accounts, running a half-marathon will not appeal to the majority of women undergoing treatments for breast cancer. However, there are reports that less intensive exercise can be of benefit, both during and following treatment. Courneya and colleagues have been involved in this area of research for many years, examining via RCTs which exercise programmes engage patients and also the barriers and predictors of exercise behaviour. In one study they randomised 242 women initiating chemotherapy treatment to resistance training, aerobic exercise or usual care for the duration of their chemotherapy regimens (mean of 17 weeks).72 Although neither aerobic nor resistance exercise significantly improved QoL in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, the programmes improved self-esteem, physical fitness, body composition and chemotherapy completion rate without causing lymphoedema or significant adverse events. At 6-month follow-up, the women were sent a questionnaire that assessed QoL, self-esteem, fatigue, anxiety, depression and exercise behaviours.73 Eighty-three per cent (201/242) responded; compared to usual care, those who participated in the resistance training maintained an increase in self-esteem. There was a reduction in anxiety in the aerobic group that had not been observed during chemotherapy. The authors also measured which factors, personal and clinical, predicted exercise training responses.74 They found patients who had a preference for resistance training had improved QoL when they were assigned to receive it, compared with usual care (P = 0.008). Patients who had no preference had improved QoL when they were assigned to receive either programme (P = 0.014). The barriers to supervised exercise varied but over half were directly attributed to the disease and side-effects of treatments.75 Exercise behaviour 6 months after the trial was predicted by a wide range of demographic, medical, behavioural, fitness, psychosocial and motivational variables, which highlights the difficulties with promoting and maintaining fitness.76 A Cochrane review of exercise in women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer that included nine controlled trials involving 452 patients concluded that physical exercise can improve physical function even during cancer treatment. This review also considered that there was still not enough evidence about the effect of exercise on outcomes such as fatigue, mood disturbances, immune function and weight gain.77

There are other forms of ‘exercise’ that may appear more attractive to patients with breast cancer, including yoga and Pilates. An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary therapy for patients with cancer, including six RCTs, concluded that yoga helped improve mood, QoL and decrease anxiety.78 More research is warranted on whether yoga can improve specific physical damage, for example arm morbidity following axillary surgery.

Conclusion

There are a large number of studies showing that the adjuvant systemic therapies that form part of the management pre- and post-breast cancer surgery impact on the quality of patients’ lives. In a recent report of 653 women with breast cancer, substantial numbers sought help with symptoms: hot flushes (41%), night sweats (36%), loss of interest in sex (30%), difficulty sleeping (25%), fatigue (22%) and extreme vaginal dryness (19%).79 Chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure was reported by 29% of the breast cancer patients seen. A wide range of management approaches were offered, with 55% of the women prescribed non-hormonal pharmacological therapies for vasomotor symptoms, including vitamin E 400 IU twice daily (21%), venlaflaxine 75 mg CR once daily (13%), clonidine 50 μg twice daily (11%), or gabapentin 300 mg three times daily (4%). As found in other studies, vasomotor symptoms, sexual dysfunction and sleep disturbance are the most distressing menopausal symptoms requiring attention. Menopausal symptom management after breast cancer is complex and demands a multidisciplinary approach with interventions appropriately tested and monitored.

References

1. Ramirez, A.J., Westcombe, A.M., Burgess, C.C., et al, Factors predicting delayed presentation of symptomatic breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999;353(9159):1127–1131. 10209975

2. Nosarti, C., Crayford, T., Roberts, J., et al, Delay in diagnosis in breast cancer. Lancet. 1999;353(9170):2154. 10382716

3. Downing, A., Prakash, K., Gilthorpe, M.S., et al, Socioeconomic background in relation to stage at diagnosis, treatment and survival in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(5):836–840. 17311024

4. Jack, R.H., Davies, E.A., Meller, H., Breast cancer incidence, stage, treatment and survival in ethnic groups in South East England. Br J Cancer 2009; 100:545–550. 19127253

5. Linsell, L., Burgess, C.C., Ramirez, A.J., Breast cancer awareness among older women. Br J Cancer 2008; 99:1221–1225. 18813307

6. Linsell, L., Forbes, L.J.L., Kapari, M., et al, A randomised controlled trial of an intervention to promote early presentation of breast cancer in older women: effect on breast cancer awareness. Br J Cancer 2009; 101:S40–S48. 19956161

7. Austoker, J., Bankhead, C., Forbes, L.J.L., et al, Interventions to promote cancer awareness and early presentation: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(S2):S31–S39. 19956160

8. Beaver, K., Luker, K.A., Owens, R.G., et al, Treatment decision making in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1996;19(1):8–19. 8904382

9. Katz, S.J., Lantz, P.M., Janz, N.K., et al, Patient involvement in surgery treatment decisions for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5526–5533. 16110013

10. Fallowfield, L., Offering choice of surgical treatment to women with breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns 1997; 30:209–214. 9104377

11. Ganz, P.A., Schag, C.A.C., Lee, J.J., et al, Breast conservation versus mastectomy: Is there a difference in psychological adjustment or quality of life in the year after surgery? Cancer. 1992;69(7):1729–1738. 1551058

12. De Haes, J.C.J.M., Curran, D., Aaronson, N.K., et al, Quality of life in breast cancer patients aged over 70 years, participating in the EORTC 10850 randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(7):945–951. 12706363

13. Survival statistics for the most common cancers: http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/survival/latestrates/; [accessed 19.11.11].

14. Engle, J., Kerr, J., Schlesinger-Raab, A., et al, Quality of life following breast conserving therapy or mastectomy: results of a 5 year prospective study. Breast. 2004;10(3):223–231. 15125749

15. Arndt, V., Stegmaier, C., Ziegler, H., et al, Quality of life over 5 years in women with breast cancer after breast conserving therapy versus mastectomy: a population based study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(12):1311–1318. 18504613

16. Collins, K.K., Liu, Y., Schootman, M., et al, Effects of breast cancer surgery and surgical side effects on body image over time. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 126:167–176. 20686836

17. Layfield, D.M., Agrawal, A., Roche, H., et al, Intraoperative assessment of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98(1):4–17. 20812233

18. Fleissig, A., Fallowfield, L.J., Langridge, C.I., et al, Postoperative arm morbidity and quality of life. Results of the ALMANAC randomised trial comparing sentinel node biopsy with standard axillary treatment in the management of patients with early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95(3):279–293. 16163445

19. Tamaki, Y., Akiyama, F., Iwase, T., et al, Molecular detection of lymph node metastases in breast cancer patients: results of a multicenter trial using the one-step nucleic acid amplification assay. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(8):2879–2884. 19351770

20. Khaddage, A., Berremila, S.-A., Forest, F., et al, Implementation of molecular intra-operative assessment of sentinel lymph node in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(2):585–590. 21378342

21. Jenkins, V., Harder, H., Babar, M., et al, A pilot study to examine the experiences and attitudes of women with breast cancer towards one versus two-step axillary surgery. Breast. 2012;21(1):72–76. 21873063

22. DCIS: http://cancerhelp/type/breastcancer/about/types/dcis-ductal carcinoma in situ; [accessed 03/12/2011].

23. Ganz, P., Quality of life issues in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010; 41:218–222. 20956834

24. Rakovitch, E., Franssen, E., Kim, J., et al, A comparison of risk perception and psychological morbidity in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;77(3):285–293. 12602928

25. van Gestel, Y.R., Voogd, A.C., Vingerhoets, A.J., et al, A comparison of quality of life, disease impact and risk perception in women with invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(3):549–556. 17140788

26. Partridge, A., Adloff, K., Blood, E., et al, Risk perceptions and psychosocial outcomes of women with ductal carcinoma in situ: longitudinal results from a cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(4):243–251. 18270338

27. Lauszier, S., Maunsell, E., Levesque, P., et al, Psychological distress and physical health in the year after diagnosis of DCIS or invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 120:685–691. 19653097

28. Kennedy, F., Harcourt, D., Rumsey, N., et al, The psychosocial impact of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): A longitudinal prospective study. Breast. 2010;19(5):382–387. 20413310

29. Raftery, J., Chorozoglou, M., Possible net harms of breast cancer screening: updated modelling of Forrest report. Br Med J 2011; 343:d7627. 22155336

30. Fallowfield, L., Cella, D., Cuzick, J., et al, Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4261–4271. 15514369

31. Ruhstaller, T., Von Moos, R., Rufibach, K., et al, Breast cancer patients on endocrine therapy reveal more symptoms when self-reporting than in pivotal trials: an outcome research study. Oncology. 2009;76(2):142–148. 19158446

32. Oberguggenberger, A., Hubalek, M., Sztankay, M., et al, Is the toxicity of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy underestimated? Complementary information from patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(2):553–561. 21311968

33. Cella, D., Fallowfield, L.J., Recognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):167–180. 17876703

34. Fallowfield, L., Cella, D., Cuzick, J., et al, Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4261–4271. 15514369

35. Fallowfield, L.J., Bliss, J.M., Porter, L.S., et al, Quality of life in the intergroup exemestane study: a randomized trial of exemestane versus continued tamoxifen after 2 to 3 years of tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):910–917. 16484701

36. Holmberg, L., Anderson, H., HABITS steering and data monitoring committees, HABITS (hormonal replacement therapy after breast cancer – is it safe?): a randomized comparison: trial stopped. Lancet. 2004;363(9407):453–455. 14962527

37. Lee, M.S., Kim, K.H., Choi, S.M., et al, Acupuncture for treating hot flashes in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115(3):497–503. 18982444

38. Borud, E.K., Alraek, T., White, A., The Acupuncture on hot flushes among menopausal women (ACUFLASH) study: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2009;16(3):484–493. 19423996

39. Hunter, M.S., The Women’s Health Questionnaire (WHQ): the development, standardisation and application of a measure of mid-aged women’s emotional and physical health. Qual Life Res 2000; 9:733–738. 10855347

40. Freeman, E.W., Sammel, M.D., Lin, H., et al, The role of anxiety and hormonal changes in menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2005;12(3):258–266. 15879914

41. Gold, E.B., Colvin, A., Avis, N., et al, Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1226–1235. 16735636

42. Elkins, G., Marcus, J., Stearns, V., et al, Randomized trial of a hypnosis intervention for treatment of hot flashes among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(31):5022–5026. 18809612

43. Nedstrand, E., Wijma, K., Wyon, Y., et al, Vasomotor symptoms decrease in women with breast cancer randomized to treatment with applied relaxation or electro-acupuncture: a preliminary study. Climacteric. 2005;8(3):243–250. 16390756

44. Nedstrand, E., Wyon, Y., Hammar, M., et al, Psychological well-being improves in women with breast cancer after treatment with applied relaxation or electro-acupuncture for vasomotor symptom. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;27(4):193–199. 17225620

45. Booth-LaForce, C., Thurston, R.C., Taylor, M.R., A pilot study of a Hatha yoga treatment for menopausal symptoms. Maturitas. 2007;57(3):286–295. 17336473

46. Hunter, M.S., Coventry, S., Hamed, H., et al, Evaluation of a group cognitive behavioural intervention for women suffering from menopausal symptoms following breast cancer treatment. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):560–563. 18646246

47. Loprinzi, C.L., Kugler, J.W., Sloan, J.A., et al, Venlafaxine in management of hot flashes in survivors of breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2059–2063. 11145492

48. Stearns, V., Slack, R., Greep, N., et al, Paroxetine is an effective treatment for hot flashes: results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):6919–6930. 16192581

49. Loprinzi, C.L., Sloan, J.A., Perez, E.A., et al, Phase III evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1578–1583. 11896107

50. Kimmick, G.G., Lovato, J., McQuellon, R., et al, Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of sertraline (Zoloft) for the treatment of hot flashes in women with early stage breast cancer taking tamoxifen. Breast J. 2006;12(2):114–122. 16509835

51. Bordeleau, L., Pritchard, K., Goodwin, P., et al, Therapeutic options for the management of hot flashes in breast cancer survivors: an evidence-based review. Clin Ther. 2007;29(2):230–241. 17472816

52. Freedman, R.R., Kruger, M.L., Tancer, M.E., Escitalopram treatment of menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2011;18(8):893–896. 21540755

53. Chin, S.N., Trinkaus, M., Simmons, C., et al, Prevalence and severity of urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal women receiving endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(2):108–117. 19433392

54. Pfeiler, G., Glatz, C., Königsberg, R., et al, Vaginal estriol to overcome side-effects of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer patients. Climacteric. 2011;14(3):339–344. 21226657

55. Baum, M., Buzdar, A.U., Cuzick, J., et al, Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2131–2139. 12090977

56. Goss, P.E., Ingle, J.N., Jose, M.D., et al, Exemestane for breast cancer prevention in post menopausal women. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2381–2391. 21639806

57. Coombes, R.C., Hall, E., Gibson, L.J., A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1081–1092. 15014181

58. Din, O.S., Dodwell, D., Winter, M.C., et al, Current opinion of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer in the UK. Clin Oncol. 2011;23(10):674–680. 21788122

59. Henry, N.L., Giles, J.T., Stearns, V., Aromatase inhibitor-associated musculoskeletal symptoms: etiology and strategies for management. Oncology. 2008;22(12):1401–1408. 19086600

60. Crew, K.D., Capodice, J.L., Greenlee, H., et al, Randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial of acupuncture for the management of aromatase inhibitor-associated joint symptoms in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1154–1160. 20100963

61. Henry, D., Robertson, J., O’Connell, D., A systematic review of the skeletal effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. I. An assessment of the quality of randomized trials published between 1977 and 1995. Climacteric. 1998;1(2):92–111. 11907921

62. Waltman, N.L., Ott, C.D., Twiss, J.J., et al, Vitamin D insufficiency and musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitor therapy. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(2):143–150. 19125120

63. Rastelli, A.L., Taylor, M.E., Gao, F., et al, Vitamin D and aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms (AIMSS): a phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(1):107–116. 21691817

64. Ganz, P.A., Kwan, L., Stanton, A.L., et al, Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1101–1109. 21300931

65. Bower, J.E., Ganz, P.A., Desmond, K.A., et al, Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):743–753. 10673515

66. Irwin, M.L., McTiernan, A., Baumgartner, R.N., et al, Changes in body fat and weight after a breast cancer diagnosis: influence of demographic, prognostic, and lifestyle factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):774–782. 15681521

67. Montel, S. Mood and anxiety disorders in breast cancer: an update. Curr Psychiat Rev. 2010; 6(1):56–63.

68. www.macmillan.org.uk/movemore; [accessed 8.08.11].

69. Department of Health UK Physical Activity Guidelines. http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2011/07/physical-activity-guidelines/; [accessed 11.07.11].

70. Morgan, W.P., Dishman, R.K. Adherence to exercise and physical activity. Quest. 2001; 53:277–278.

71. http://www.thisisbristol.co.uk/Fundraising-couple-race-line/story-11284208-detail/story.htmlhttp://runningtimes.com/Print.aspx?articleID=12936; [accessed 29.06.12].

72. Courneya, K.S., Segal, R.J., Mackey, J.R., et al, Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomised controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25:4396–4404. 17785708

73. Courneya, K.S., Segal, R.J., Gelmon, K., et al, Six month follow up of patient rated outcomes in a randomised controlled trial of exercise training during breast cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16:2572–2578. 18086760

74. Courneya, K.S., Segal, R.J., Gelmon, K., et al, Barriers to supervised exercise training in a randomised controlled trial of breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Ann Behav Med 2008; 35:116–122. 18347912

75. Courneya, K.S., Friedenreich, C.M., Reid, R., et al, Predictors of follow-up exercise behavior 6 months after a randomised trial of exercise training during breast cancer chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009; 114:179–187. 18389368

76. Courneya, K.S., Karvinen, K.H., McNeely, M.L., et al, Predictors of adherence to supervised and unsupervised exercise in the Alberta physical activity and breast cancer prevention trial. J Phys Act Health 2011; Sept 13. Epub ahead of print. 21953311

77. Markes, M., Brockow, T., Resch, K.-L., Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 4, doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005001.pub281. CD005001. 101002

78. Smith, K., Pukall, C., An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):465–475. 18821529

79. Hickey, M., Emery, L.I., Gregson, J., et al, The multidisciplinary management of menopausal symptoms after breast cancer: a unique model of care. Menopause. 2010;17(4):727–733. 20512079