Psychosocial Considerations in the Evaluation and Treatment of Dentofacial Deformities

• Psychosocial Aspects to Consider Before Surgery

• Psychological Functioning in the Individual With a Facial Deformity

• Patient and Family Decision for or Against the Correction of a Dentofacial Deformity

• Patient and Family Education Regarding Convalescence After Orthognathic Surgery

• Patient-Centered Assessment of Surgical and Orthodontic Outcomes

• Controversies Surrounding “Successful” Orthognathic Outcomes

The initial discussion regarding the need for orthognathic surgery may come as a surprise to the patient and his or her family. This is especially true for the individual whose jaw dysmorphology occurred gradually during facial development, without special attention being drawn to it all of a sudden as would occur from a traumatic event, a birth defect, or after tumor resection.9,10,37,68,71,80,81,101,103 Although they have typically been aware of the malocclusion and the associated facial characteristics for at least several years, the patient and his or her family generally assume that orthodontics alone or some other minimally invasive approach is all that will be required for treatment.87 The orthodontist may have already exhausted the patient and his or her family’s energy and resources with several years of treatment to “avoid surgery” before finally “giving up.” The family may have inaccurate preconceived ideas about the surgery and the patient’s expected convalescence. The decision-making role of the parents and the compliance (i.e., the attitude) of the adolescent patient will also be important. Any dysfunctional family interactions involving the mother, the father, the patient, or the patient’s siblings, stepparents, or grandparents at this moment of stress (i.e., when a decision is needed) may also come into play. From the adolescent’s point of view, social interactions with his or her peers and concerns about the interpretation (by others) of any change in his or her appearance—as well as his or her evolving self-image and identity—will also have an impact on the situation in ways that are ongoing and somewhat unpredictable.

Research confirms a correlation between an adolescent’s self-reporting of improved appearance ratings and a decrease in social, physical, and psychological problems after successful reconstruction.58,67,73,78 Patel and Kapp-Simon prospectively studied 70 teenagers who were slated to undergo orthognathic surgery.69 Before surgery, 78% stated that a functional reason was their primary motivation for undergoing orthognathic surgery. Not surprisingly, before surgery, the adolescents rated their appearance significantly less favorable than their parents did. Two years after surgery, the adolescents reported significantly increased self-confidence, and a majority (58%) felt that they had achieved improvements in their facial appearance as a result of surgery. They stated that improvements in their facial appearance would be a motivating factor for them to undergo similar surgery again. It would appear that, when all is said and done, adolescents—like adults—rate the enhancement of their facial appearance as a high priority when measuring the success or failure of their orthognathic procedures. Experience confirms it is better to openly discuss facial aesthetic aspects before surgery. This encourages the clinician to set realistic objectives, and it forces the patient and the family to confront their outcome expectations in advance.

Both adolescents and adults undergoing orthognathic surgery should be screened to assess emotional baseline functioning as well as psychological readiness for surgery. The pre-surgical mental health screening should clarify any past or current symptoms of depression, anxiety disorders, panic attacks, aggression, drug/alcohol use, eating disorders, school-related problems, family or social (peer) dysfunctional relationships.4

Psychosocial Aspects to Consider Before Surgery

Personal Motivation

The individual’s personal motivation to seek the correction of a dentofacial deformity is an important factor for clinicians to consider (Figs. 7-1 through 7-5).* In 2000, Rivera and colleagues surveyed 142 patients regarding their reasons for choosing to undergo orthognathic surgery.86 Seventy-one percent indicated facial aesthetic concerns, 47% stated functional issues, and 28% confirmed temporomandibular disorders as their reasons for seeking treatment. In 2007, Narayanan and colleagues surveyed 50 patients who sought orthognathic surgery and found that, for the majority, facial aesthetics rather than the correction of their occlusions was the primary motivating factor.59 In 2007, Stirling and colleagues conducted a questionnaire and interview survey of individuals who had undergone orthognathic surgery. The 46 interviewed patients stated that their primary motivations generally included both “improvement of the occlusion and to gain a more normal facial appearance.”97 More recently, Proothi, Drew, and Sachs completed a retrospective survey of 501 individuals who underwent orthognathic surgery to determine why they sought the procedures.83 The survey group was 43% male and 57% female, and the individuals ranged in age from 12 to 45 years. Seventy-six percent stated that facial appearance was negatively affected by their pretreatment jaw condition, but only 15% claimed that their appearance was their primary motivation for undergoing surgical evaluation. Thirty-six percent stated that their occlusion was the primary motivating force. Interestingly, 33% admitted to having significant speech difficulties, and 15% complained of swallowing problems that resulted from their presenting jaw deformity.

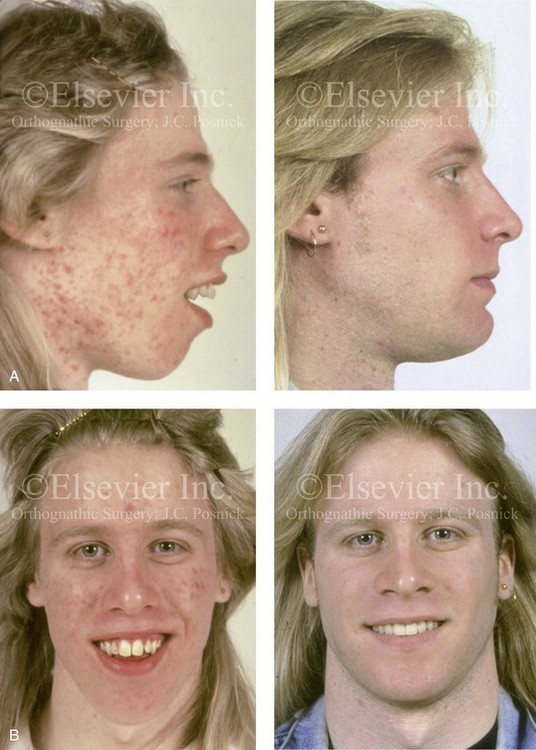

Figure 7-1 A 17-year-old boy who was born with a nonprogressive congenital myopathy was referred by an orthodontist for surgical evaluation. The lack of masticatory muscle strength resulted in a constant open mouth posture. The long face growth pattern is characterized by vertical maxillary excess; a clockwise-rotated retrusive mandible; a vertically long and retrusive chin; and an Angle Class II anterior open-bite malocclusion. The patient underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. Four bicuspid extractions relieved dental crowding. This was followed by surgery that included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical intrusion and horizontal advancement); bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); and osseous genioplasty (vertical reduction and horizontal advancement). A, Profile views before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction.

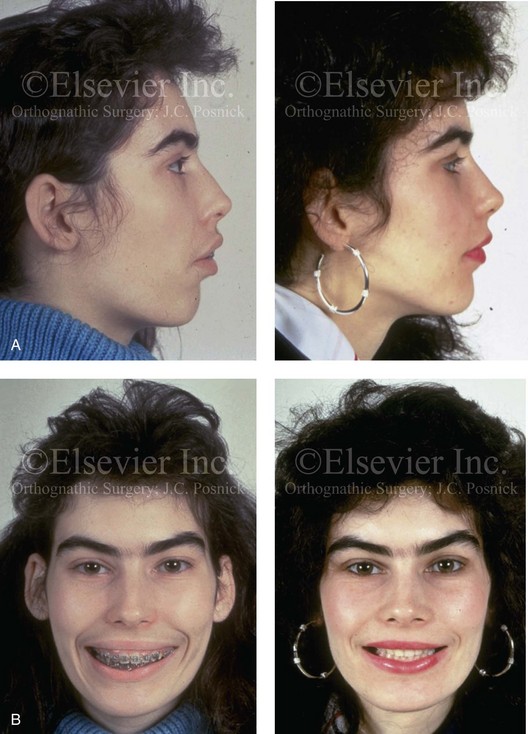

Figure 7-2 A 15-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She had a long face growth pattern and a Class II anterior open-bite malocclusion. She had been treated for several years with orthodontics alone, and this included four bicuspid extractions. The anterior open bite was essentially closed, with only minor degrees of malocclusion. The history and physical examination confirmed lifelong nasal obstruction, heavy snoring, and the suggestion of sleep apnea. Facial aesthetic concerns of the patient and her family included an awareness of a gummy smile, severe lip strain, a weak profile, and an irregular shape and position of the lips. The family agreed to an orthognathic approach. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical shortening and horizontal advancement with counterclockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split osteotomies (horizontal advancement and counterclockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (horizontal advancement and vertical shortening); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor recontouring. A, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction.

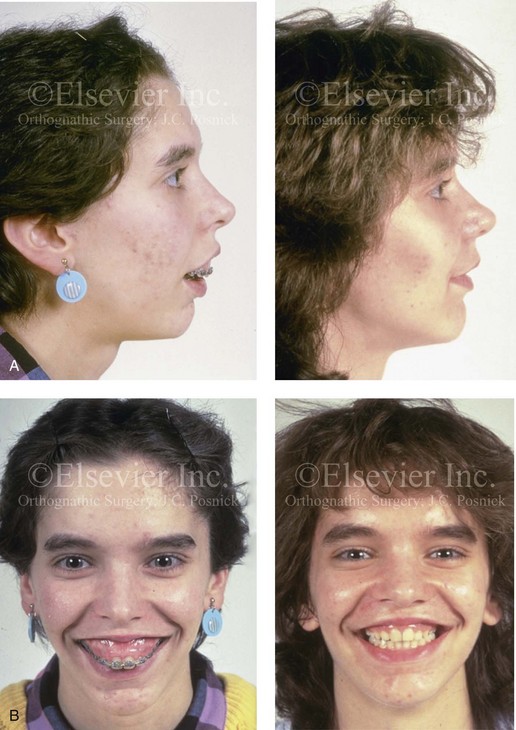

Figure 7-3 A 16-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation. She had a long face growth pattern in combination with asymmetrical mandibular deficiency. This resulted in difficulty with speech articulation, swallowing, chewing, and lip closure/posture. Facial aesthetic awareness of a gummy smile, lip incompetence, a weak profile, and lip irregularities was discussed. With orthodontic decompensation complete, orthognathic surgery was carried out. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments, with first bicuspid extractions (vertical retrusion, arch form correction, and counterclockwise rotation); bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement, counterclockwise rotation, and asymmetry correction); and septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal floor contouring. A, Profile views before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment.

Figure 7-4 A 14-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist for surgical evaluation of a dentofacial deformity. She had a long face growth pattern that presented with excessive vertical height and significant horizontal projection and narrowness of the maxilla and the midface. She had limited airflow to the nose, severe lip incompetence, and the impression of a weak chin. Several years of orthodontics have already been carried out, and she agreed to surgical reconstruction. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in three segments with first bicuspid extractions (vertical intrusion, horizontal setback, and arch correction) as well as septoplasty, inferior turbinate reduction, and nasal recontouring. A, Profile views before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction.

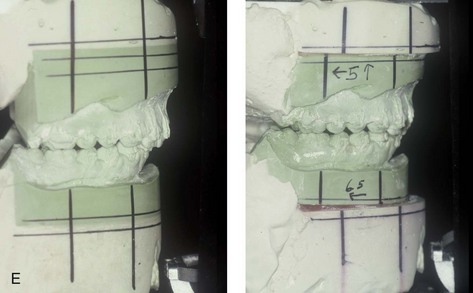

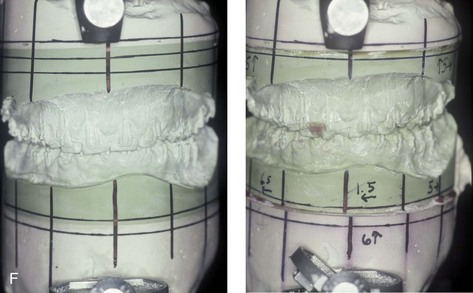

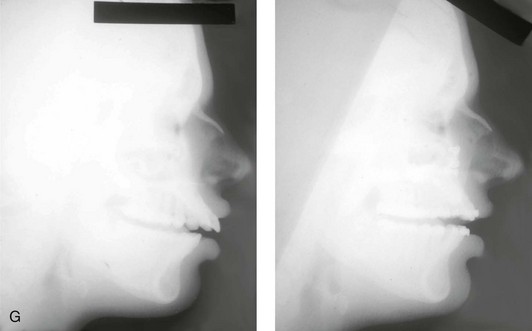

Figure 7-5 A 16-year-old congenitally blind girl presented with maxillary and mandibular protrusion and anterior open-bite malocclusion. Although she was unable to visualize the deformity, she felt self-conscious after years of teasing as a result of her facial appearance and her difficulties with chewing, swallowing, and speech articulation. The patient underwent a combined orthodontic and surgical approach. The procedures performed included a maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (vertical intrusion and horizontal setback) and bilateral sagittal split osteotomies of the mandible (horizontal setback). A, Frontal views before and after reconstruction. B, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. C, Profile views before and after reconstruction. D, Occlusal views before and after reconstruction. E and F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Baseline Mental Health

Individuals who do not have sufficient preoperative psychological or emotional stability are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, or panic attacks and to demonstrate difficulty complying with treatment demands during the early postoperative phase.16,17,21,27 They will also have greater difficulty with an outcome that does not meet their preconceived and often incompletely articulated expectations. If so, after surgery, they may become easily frustrated and then angry, and this may involve a loss of confidence in the surgeon. They may break off communication and seek additional opinions to justify their concerns. Some may even resort to litigation should a perceived complication or suboptimal outcome occur. Recognizing and addressing these patient-specific tendencies before surgery is the best way to limit or mitigate problems after surgery.

After an initial screening examination, a more in-depth psychological evaluation may be beneficial.8,18,24,96 The patient and his or her family’s motivation and the patient’s readiness for surgery should also be assessed. Unless a sufficient support system is in place, the stress of the necessary convalescence is likely to worsen any premorbid conditions in the patient. An initial screening that results in red flags for potential emotional problems is best followed up with a more focused psychological evaluation. The patient’s therapist should give clearance that the individual is considered emotionally stable enough to undergo the proposed treatment. When the treating clinicians (i.e., the surgeon, the orthodontist, and the general physician) have knowledge of the patient’s premorbid tendencies, coping strategies can be instituted proactively to minimize postoperative stress. The treating mental health professional should be available to the patient, the family, and the surgical team during hospitalization, after discharge, and throughout the patient’s convalescence.

Baseline Eating Disorders

Clinical studies indicate that between 0.5% and 1.0% of late adolescent and young adult women meet the criteria for anorexia nervosa, and between 1% and 3% meet the criteria for bulimia nervosa.92 Eating disorders are multi-determined problems, and they are most commonly recognized among female adolescents. Risk factors may include a perfectionist personality type, a family history of an eating disorder, a history of trauma, a tendency toward feelings of inadequacy, and low self-esteem despite external accomplishments. Patients with eating disorders often exhibit rigid cognitive patterns that are characterized by an all-or-nothing way of thinking.

Orthognathic procedures will significantly alter the diet (i.e., liquids only) and appetite level, with an expected change in nutritional intake for at least 5 weeks. Significant weight loss during the initial 2 weeks of recovery is to be expected, even among healthy individuals. The question is raised as to whether or not these dietary and postsurgical metabolic changes will tend to exacerbate a baseline eating disorder. Maine and Goldberg completed a study to determine if an elective dental manipulation—which, by necessity, results in eating discomfort and dietary restrictions—would likely influence the recovery of or result in a relapse for an individual with a baseline eating disorder.54 Three questions concerning dental and maxillofacial procedures were added to a standard questionnaire assessment of a consecutive series of 97 individuals who were entering an eating disorder therapy program. The additional questions were designed to determine the influence of dental and maxillofacial interventions on individuals with baseline eating disorders. All 97 study subjects complied with the questionnaire; 75 of the study patients were 25 years old or younger, and 53 were diagnosed with anorexia nervosa.

Social Interaction Issues

Ongoing family or social peer conflicts or greater-than-average worries expressed by the individual or his or her family regarding the surgery, the preparation for the surgery, or the anticipated recovery period are red flags.1,29,33,41 When considering the timing of surgery for the adolescent or young adult, the family should take into account the anticipated impact on the patient’s everyday school and social activities, including examination schedules, college applications and interviews, and participation in sports activities. The surgeon’s ability to provide a clear picture of the expected recovery time and the patient’s ability to return to partial and regular activities is important and will vary according to the patient’s age and stage in life (e.g., adolescent, college or graduate student, middle-aged adult with family and work commitments). Clarifying anticipated postoperative limitations in physical, cognitive, and emotional activities is important to setting the stage for a successful outcome.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

It is estimated that more than 5% of individuals who are seeking cosmetic surgery consults have body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).14,19,65,91 BDD is a somatoform disorder that involves a preoccupation with a slight or imagined defect in some aspect of the individual’s physical appearance that leads to a significant disruption of daily functions. It is important to distinguish an individual with a legitimate cosmetic or functional concern from one who is hyperconcerned about minor imperfections of some aspect of his or her face.

Cunningham and colleagues documented that a percentage of individuals who request orthognathic surgery will have underlying BDD.19 A surgical procedure to improve facial aesthetics typically does not change or fully satisfy the appearance concerns of these individuals. Orthognathic procedures may even exacerbate these symptoms, despite the clinician’s accurate assessment of the presenting deformity and the likelihood of the achievement of a favorable morphologic and functional result. No matter how skilled the surgeon and how perfect the end result, dissatisfaction should be expected when treating a patient with BDD; therefore, surgery should be avoided unless extensive counseling is performed before the proposed procedure. The development of an effective psychosocial screening interview method or the use of a self-reporting assessment survey to help identify individuals with BDD is needed in clinical practice.

Psychological Functioning in the Individual With a Facial Deformity

A spectrum of studies report that individuals with facial deformities have a higher prevalence of psychological problems that may interfere with the ability of these individuals to function socially. The psychological problems described include (1) a reduced quality of life; (2) a tendency to internalize behavior; (3) low self-esteem; (4) an increased tendency toward depression; and (5) anxiety.13,100 Interestingly, studies confirm that it is the patient’s satisfaction with his or her own appearance rather than an objective standard of the severity of the deformity that influences these psychological problems. The individual’s personal dissatisfaction with his or her facial appearance seems to be a better predictor of higher rates of anxiety and depression and lower rates of favorable quality of life and self-esteem as compared with the clinician’s impression of how the individual looks.

Versnel and colleagues conducted research that involved adults with facial disfigurement and confirmed that a subset of these individuals demonstrated psychological dysfunctions: 11% had anxiety; 6% had depression; 10% had externalized problems; and 25% had a tendency to internalize problems.100 The authors clarified that either an actual or a perceived facial deformity can be a significant stressor in life to which the affected individual must adapt.13,55,72,84,89,93 The study also looked at differences between congenital and acquired facial deformities. Many of the study patients that acquired their facial deformities later in life (i.e., those that were related to trauma or tumors) had a more difficult time, which implied that a significant percentage of those with congenital conditions had eventually adapted to their physical problems. The authors surmised that, because the congenital patients had no knowledge of how life would have been without facial disfigurement, their adaptation was different and often more complete.

Patient and Family Decision for or Against the Correction of a Dentofacial Deformity

• The surgical objectives, anticipated treatment outcomes, and limitations with regard to predicting exact results

• How the surgery will fit in with the overall treatment plan (e.g., orthodontics, dental rehabilitation, speech therapy, airway management)

• The potential risks, complications, and limitations of each planned procedure

• What to expect during hospitalization (e.g., discomfort, swelling, hygiene needs, limitations in activity and diet, limitations in mouth opening and lip seal control, difficulties with speech and communication)

• What to expect after discharge from the hospital (i.e., ongoing convalescence needs)

• What the patient and the family must do to maximize a favorable outcome

• When the patient can expect to resume a more normal routine

Information should be provided in a number of different ways, which may include (1) verbal discussion; (2) a demonstration of surgical technique on a model skull; (3) showing similar patients’ before and after photographs to demonstrate the potential range of results; (4) reviewing and discussing the patient’s own photographs, dental models, and radiographs; and (5) providing reinforcement with detailed and readable written material.32,66 The option of discussing details with another patient of the same approximate age and sex who has undergone similar surgery may also be helpful.

Patient and Family Education Regarding Convalescence After Orthognathic Surgery

Early after surgery, while in hospital, the individual who (1) appears to be more irritable and non-communicative; (2) complains of greater-than-expected levels of pain with demands for continued narcotics; and (3) is having more-than-average difficulty complying with personal care needs (i.e., achieving hydration and caloric requirements, oral and body hygiene requirements, and adequate ambulation) may be a candidate for a demanding convalescence.77,79 The adolescent may comply just enough (e.g., ambulation, fluid intake) to get out of the hospital. After he or she gets home, unless the parents are able to remain firm concerning patient care needs, the adolescent’s feeling of self-consciousness or uncertainty about temporary levels of facial swelling, drooling, loss of appetite, and difficulty with breathing and speech can lead to further social withdrawal and non-compliance. This may also lead to overreliance on narcotic medication with the assumption that pain is the problem. Unless this type of patient is closely monitored, dehydration, hypoglycemia, and depression will set in. Even if this phase of convalescence is managed, some adolescents express unwillingness to return to school within the expected time frame as a result of concern about the reactions of their peers. Many will lose this reluctance when a friend is invited to their home to break the ice. As the recovering patient perceives positive affirmation from their family and friends regarding the changes brought about by surgery, their social hesitation generally subsides.

The clinicians (i.e., the surgeon, the orthodontist, and the treating dentist) often judge success on the basis of measurable standards of (1) an “improved” profile; (2) achieving normative cephalometric radiograph measurements; (3) a corrected occlusion; and (4) achieving specific wound-healing parameters. Discussions with the patient and family should not overlook psychosocial aspects. Individuals with baseline evidence of mental health issues are likely to have a greater-than-average need for positive reinforcement, and they may also require more formal psychological support throughout the perioperative process. The success of treatment should not be thought of solely in terms of improving head and neck function or the achievement of strict numerical parameters. The potential for orthognathic procedures to have profound effects on the individual’s psychosocial health—whether positive or negative—should not be underestimated (see Figs. 7-1 through 7-5). During convalescence and after the return to school or work, the clinician should ask the patient about his or her interactions with others regarding the recent surgery to determine if a more in-depth discussion is required.

Patient-Centered Assessment of Surgical and Orthodontic Outcomes

Many public health experts believe that the ultimate determination of a treatment’s quality and success is its effectiveness for producing not just physical health as judged by clinicians but also for resulting in the individual’s personal satisfaction.5,22,23,38,44,45,51,56,57,59,82,94,95,98 Traditional surgical outcome measurements such as mortality and improvement in physiologic parameters (e.g., blood pressure) find limited application in the treatment of dentofacial deformities. At the same time, traditional orthodontic parameters of accomplishing specific change in millimeter distances or degrees of angulation at standard anatomic sites do not necessarily correlate with patient satisfaction. Despite the importance of satisfaction as a proxy for quality, the concept of patient-perceived well-being can be difficult to define. When developing a patient questionnaire for use as a self-administered survey after orthognathic surgery, consideration should be given to the features of care that influence the patient’s satisfaction. These features may be categorized into one of the following domains: (1) aesthetic outcomes; (2) functional outcomes; or (3) psychological outcomes. A review of the literature concerning patient-centered outcome assessments after orthognathic surgery sheds light on the issue of how to achieve patient-based satisfaction after treatment.

Orthognathic Surgery and Health-Related Quality of Life: Review of Study

Posnick and colleagues reported on data from a health-related quality-of-life survey that was completed postoperatively by a consecutive series of patients who had undergone bimaxillary orthognathic surgery in combination with intranasal and other adjunctive procedures. The survey was filled out by each study patient only after recovery from surgery and after all orthodontic therapy and dental rehabilitation was complete (i.e., a minimum of 6 months after surgery).82

Controversies Surrounding “Successful” Orthognathic Outcomes

Not surprisingly, orthognathic surgery patients’ self-verification needs (i.e., the need to feel accepted) are generally an important factor in their judgment of successful treatment. This need cannot be overlooked if a favorable result is to be achieved.* For example, patients who undergo orthognathic procedures may expect to draw attention to their new appearance. If orthodontic treatment and orthognathic surgery result in positive and praising feedback from those in their social circles, self-verification is fulfilled, and they are likely to be satisfied. Some orthognathic patients may have realistic expectations but do not have a supportive social network of family and friends to fulfill their self-verification needs. Negative appearance–related commentary (e.g., teasing by peers at school, or more subtle forms of negative feedback by adults) has been shown to significantly affect body image and psychosocial functioning after surgery. If the comments of others are not positive or do not meet personal expectations (which can be unrealistically high), self-verification needs are not fulfilled, and the patient is likely to be dissatisfied. One concrete self-verification need after orthognathic surgery is a “normal” occlusion. The feedback that an individual receives from his or her treating clinicians (i.e., the orthodontist, the restorative dentist, and the surgeon) about his or her occlusion would be expected to influence that individual’s level of satisfaction.

Kiyak and colleagues completed a study that evaluated the psychological changes in patients who were undergoing orthognathic surgery.46–51 They used a standardized questionnaire before and at intervals that extended for 2 years after surgery. The data for all six measurement periods (2 weeks preoperatively, in the hospital, and 2 weeks, 4 months, 8 months, and 2 years postoperatively) were available for 46 patients. Several important findings from this research included the following:

1. Complaints of functional head and neck problems decreased significantly from before surgery to 24 months after surgery.

2. A significant percentage of patients (49%) continued to report lip paresthesia 2 years after surgery.

3. The incidence of early postsurgical problems or complaints (i.e., at 2 weeks) had no consistent effect on the satisfaction expressed with longer-term surgical outcomes (i.e., at 2 years).

4. The satisfaction expressed by patients with surgical outcomes at 4 months remained high throughout the postoperative course (i.e., at 2 years).

5. Self-esteem appeared to rise in anticipation of surgery (i.e., at 2 weeks preoperatively) but to decline at 8 months after surgery. The patients’ self-esteem then rose again as documented at 24 months after surgery. Interestingly, on average, self-esteem never reached the high expectations of the surgical outcome that the patients had expressed at 2 weeks before surgery.

6. Body image showed a decline at 9 months after surgery as compared with its highest point. Fortunately, the overall body image at 2 years after surgery was significantly more positive than it was at 2 weeks before surgery.

On the basis of this data, Kiyak’s group suggests that, if feasible, clinicians should maintain periodic contact with their orthognathic surgery patients for at least 2 years after surgery.46–51 Although clinician interactions with the patient immediately after surgery generally fall to the surgeon (i.e., at 0 to 5 weeks), during the intermediate stage after surgery (i.e., 1 to 12 months), clinician feedback primarily falls to the orthodontist and the general dentist. According to the study, at 6 to 12 months after surgery, psychological unevenness for the patient is not uncommon. The patient and the orthodontist may experience conflict regarding the importance of “finishing the bite” and the timing of the completion of treatment. The patient may become adamant that the braces be removed for a specific social event (e.g., graduation, yearbook photographs), whereas the orthodontist may wish to continue detailing the bite. The orthodontist may focus on dental aspects that are considered to be of less immediate importance from the patient’s perspective. At the same time, the patient may have concern about persistent paresthesia (i.e., of the inferior alveolar and infraorbital nerves) and whether this is a complication or an expected consequence of the jaw surgery. If accurate information was given before surgery and if the lines of communication remain open between the patient and the surgeon, a favorable resolution of this issue is likely. The orthodontist should be aware of the expected progression of sensory recovery and suggest a return visit to the surgeon if he or she perceives a potential conflict. If instead the orthodontist, the restorative dentist, or the office personnel (e.g., the hygienist, the dental assistant) make off-the-cuff disparaging remarks about the patient’s facial aesthetics, occlusion, or incomplete facial sensory return, then the patient may assume the worst.

At the conclusion of their study (i.e., 24 months after surgery), Kiyak and colleagues found that a majority of patients had achieved their personal dental (occlusal) or jaw function objectives.46–51 Nevertheless, a minority of the subjects continued to have lingering concerns. If the patient perceived that the facial aesthetic improvements did meet his or her personal expectations, then overall satisfaction was high, regardless of any residual functional complaints (e.g., paresthesia, dysesthesia, temporomandibular disorder, occlusal imperfection). The majority of the orthognathic patients in the study by Kiyak and colleagues did in fact perceive facial aesthetic improvements and were therefore pleased.

Lee and colleagues completed a study to evaluate the patient-centered assessment of health at 6 weeks and then 6 months after orthognathic surgery.53 Their 36 study patients were evaluated at intervals that included baseline/presurgery; 6 weeks postoperatively; and 6 months postoperatively. A standardized health-related survey was given at each time interval. The results of this study demonstrated a significant deterioration in both the physical and mental health of the patients soon after surgery (at 6 weeks) as compared with baseline. This matches the expected signs and symptoms that are typically observed soon after surgery. At 6 months after surgery, there was a statistical return to baseline levels in combination with significant improvements in several of the parameters that were measured. The authors concluded that significant positive changes in quality of life occurred after orthognathic surgery in the majority of patients when their healing was complete. There was a marked but transient deterioration in many aspects related to physical and emotional well-being during the early postoperative period (i.e., the first 6 weeks after surgery). This was followed by significant improvements that were documented by 6 months after surgery.

References

1. Adams, GR. The effects of physical attractiveness on the socialization process. In: Lucker GW, Ribbens KA, McNamara JA, eds. Psychological aspects of facial form. Craniofacial Growth Series Monograph No. 11. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press; 1981:25–47.

2. Athanasiou, AE, Melsen, B, Eriksen, J. Concerns, motivations and experience of orthognathic surgery patients: a retrospective study of 152 patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1989; 4:47–55.

3. Bell, R, Kiyak, HA, Joondeph, DR, et al. Perceptions of facial profile and their influence on the decision to undergo orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod. 1985; 88:323–332.

4. Bellucci, CC, Kapp-Simon, KA. Psychological considerations in orthognathic surgery. Clin Plastic Surg. 2007; 34:e11–e16.

5. Bennett, ME, Phillips, CL. Assessment of health-related quality of life for patients with severe skeletal disharmony: a review of the issues. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1999; 14:65.

6. Berscheid, E. An overview of the psychological effects of physical attractiveness. In: Lucker GW, Ribbons KA, McNamara JA, eds. Psychological aspects of facial form, Craniofacial Growth Series Monograph No. 11. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press; 1981:1–23.

7. Bertolini, F, Russo, V, Sansebastiano, G. Pre- and postsurgical psycho-emotional aspects of the orthognathic surgery patient. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2000; 15:16–23.

8. Blinder, D, Rotenberg, L, Taicher, S. Conversion disorder after maxillofacial trauma and surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 25:116.

9. Broder, HL. Psychological research of children with craniofacial anomalies: review, critique and implications for the future. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997; 34:402.

10. Bull, R, Rumsey, N. The social psychology of facial appearance. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1988.

11. Chen, B, Zhang, ZK, Wang, X. Factors influencing postoperative satisfaction of orthognathic surgery patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2002; 17:217–222.

12. Cheng, LHH, Roles, D, Telfer, MR. Orthognathic surgery: the patient’s perspective. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998; 36:261.

13. Clifford, E, Crocker, EC, Pope, BA. Psychological findings in the adulthood of 98 cleft lip-palate children. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972; 50:234–237.

14. Crerand, C, Franklin, M, Sarwer, DB. Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006; 118:167.

15. Crowell, NT, Sazima, HJ, Elder, ST. Survey of patients’ attitudes after surgical correction of prognathism: study of 33 patients. J Oral Surg. 1970; 28:818–822.

16. Cucalon, A, Smith, RJ. Relationship between compliance by adolescent orthodontic patients and performance on psychological tests. Angle Orthod. 1990; 60:107.

17. Cunningham, SJ, Hunt, NP, Feinmann, C. Psychological aspects of orthognathic surgery: a review of the literature. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1995; 10:159.

18. Cunningham, SJ, Feinmann, C, Horrocks, EN. Psychological problems following orthognathic surgery. J Clin Orthod. 1995; 29:755.

19. Cunningham, SJ, Bryant, CJ, Manisali, M, et al. Dysmorphophobia: recent developments of interest to the maxillofacial surgeon. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 34:368.

20. Cunningham, SJ, Crean, SJ, Hunt, NP, et al. Preparation, perceptions and problems: a long-term follow-up study of orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1996; 11:41–47.

21. Cunningham, SJ, Feinmann, C. Psychological assessment of patients requesting orthognathic surgery and the relevance of body dysmorphic disorder. Br J Orthod. 1998; 25:293.

22. Cunningham, SJ, Garratt, AM, Hunt, NP. Development of a condition-specific quality of life measure for patients with dentofacial deformity: I. Reliability of the instrument. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000; 28:195.

23. Cunningham, SJ, Garratt, AM, Hunt, NP. Development of a condition-specific quality of life measure for patients with dentofacial deformity: II. Validity and responsiveness testing. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002; 30:81.

24. De Sousa, A. Psychological issues in oral and maxillofacial reconstructive surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998; 46:661.

25. Eagly, AH, Ashmore, RD, Makhijani, IVIG, Longo, LC. What is beautiful is good, but…: a meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychol Bull. 1991; 110:109–128.

26. Finlay, PM, Atkinson, JM, Moos, KF. Orthognathic surgery: patient expectations; psychological profile and satisfaction with outcome. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995; 33:9–14.

27. Fitts, WH. Manual for the Tennessee Department of Mental Health Self-Concept Scale. Nashville, Tenn: Department of Mental Health; 1965.

28. Flanary, CM, Alexander, JM. Patient responses to the orthognathic surgery experience: factors leading to dissatisfaction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983; 41:770.

29. Flanary, CM, Barnwell, GM, Jr., Alexander, JM. Patients’ perception of orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod. 1985; 88:137.

30. Flanary, CM, Barnwell, GM, VanSickels, JE, et al. Impact of orthognathic surgery on normal and abnormal personality dimensions: a 2-year follow-up study of 61 patients. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1990; 98:313.

31. Fonsecca, RJ, Baily, LT, Proffitt, WR, et al, Patient selection for orthognathic surgery. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; vol 2. Saunders, Philadelphia, 2000:3–4.

32. Forssell, H, Finne, K, Forssell, K, et al. Expectations and perceptions regarding treatment: a prospective study of patients undergoing orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998; 13:107.

33. Frost, V, Peterson, G. Psychological aspects of orthognathic surgery: how people respond to facial change. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991; 71:538.

34. Garvill, J, Garvill, H, Kahnberg, KE, Lundgren, S. Psychological factors in orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1992; 20:28–33.

35. Haimovitz, D, Lansky, LM, O’Reilly, P. Fluctuations in body satisfaction across situations. Int J Eat Disord. 1993; 13:77.

36. Hakman, ECJ. Psychological studies on orthognathic surgery. In: De Beaufort I, Hilhorst M, Holm S, eds. In the eye of the beholder. Ethics and medical change of appearance. Copenhagen: Scandinavian University Press; 1996:48–75.

37. Harper, DC. Children’s attitudes to physical differences among youth from Western and non-Western cultures. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1995; 32:114.

38. Hatch, JP, Rugh, JD, Clark, GM, et al. Health-related quality of life following orthognathic surgery. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998; 13:67.

39. Hatch, JP, Rugh, JD, Bays, RA, et al. Psychological function in orthognathic surgical patients before and after bilateral split osteotomy with rigid and wire fixation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999; 115:536.

40. Heldt, L, Haffke, EA, Davis, LF. The psychological and social aspects of orthognathic treatment. Am J Orthod. 1982; 82:318.

41. Holman, AR, Brumer, S, Ware, WH, et al. The impact of interpersonal support on patient satisfaction with orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995; 53:1289.

42. Hoppenreijs, TJM, Hakman, ECJ, Van’t Hof, MA, et al. Psychological implications of surgical-orthodontic treatment in patients with anterior open bite. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1999; 14:101–112.

43. Hunt, OT, Johnston, CD, Hepper, PG, et al. The psychosocial impact of orthognathic surgery: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2001; 120:490.

44. Hutton, CE. Patients’ evaluation of surgical correction of prognathism: survey of 32 patients. J Oral Surg. 1967; 25:225–228.

45. Juggins, KJ, Nixon, F, Cunningham, SJ. Patient- and clinician-perceived need for orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005; 128:697.

46. Kiyak, HA, Hohl, T, Sherrick, P, et al. Sex differences in motives for and outcomes of orthognathic surgery. J Oral Surg. 1981; 39:757–764.

47. Kiyak, HA, McNeill, RW, West, RA, et al. Predicting psychologic responses to orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982; 40:150–155.

48. Kiyak, HA, West, RA, Hohl, T, et al. The psychological impact of orthognathic surgery: a 9-month follow-up. Am J Orthod. 1982; 81:404–412.

49. Kiyak, HA, Hohl, T, West, RA, et al. Psychologic changes in orthognathic surgery patients: a 24-month follow up. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984; 42:506.

50. Kiyak, HA, McNeill, RW, West, RA. The emotional impact of orthognathic surgery and conventional orthodontics. Am J Orthod. 1985; 88:224.

51. Kiyak, HA, Zeitler, DL. Self-assessment of profile and body image among orthognathic surgery patients before and two years after surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 46:365–371.

52. Lazaridou-Terzoudi, T, Kiyak, HA, Moore, R, et al. Long-term assessment of psychological outcome of orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61:545.

53. Lee, S, McGrath, C, Samman, N. Impact of orthognathic surgery on quality of life. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008; 66:1194–1199.

54. Maine, M, Goldberg, MH. The role of third molar surgery in the exacerbation of eating disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001; 59:1297–1300.

55. Marcusson, A, List, T, Paulin, G, Akerlind, I. Reliability of a multidimensional questionnaire for adults with treated complete cleft lip and palate. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2001; 35:271–278.

56. Modig, M, Andersson, L, Ward, I. Patients’ perception of improvement after orthognathic surgery: pilot study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 44:24.

57. Montegi, E, Hatch, JP, Rugh, JD, Yamagichi, H. Health-related quality of life and psychosocial function 5 years after orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003; 124:138.

58. Murray, JE, Mulliken, JB, Kaban, IB, et al. Twenty-year experience in maxillofacial surgery: an evaluation of early surgery on growth function and body image. Ann Surg. 1979; 190:320.

59. Narayanan, V, Guhan, S, Sreekumar, K, et al. Self-assessment of facial form oral function before and after orthognathic surgery: a retrospective study. Indian J Dent Res. 2008; 19:12.

60. Newton, JT, Minhas, G. Exposure to “ideal” facial images reduces facial satisfaction: an experimental study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005; 33:410.

61. Nurminen, L, Pietila, T, Vinkka-Puhakka, H. Motivation for and satisfaction with orthodontic-surgical treatment: a retrospective study of 28 patients. Eur J Orthod. 1999; 21:79.

62. Oland, J, Jensen, J, Melsen, B. Factors of importance for the functional outcome in orthognathic surgery patients: a prospective study of 118 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 68:2221.

63. Oland, J, Jensen, J, Elklit, A, et al. Motives for surgical-orthodontic treatment and effect of treatment on psychosocial well-being and satisfaction: a prospective study of 118 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:104–113.

64. Oland, J, Jensen, J, Papadopoulos, MA, Melsen, B. Does skeletal facial profile influence preoperative motives and postoperative satisfaction? A prospective study of 66 surgical-orthodontic patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:2025–2032.

65. O’Regan, J, Dewey, M, Slade, P, Lovius, B. Self-esteem and aesthetics. Br J Orthod. 1991; 18:111–118.

66. Ostler, S, Kiyak, HA. Treatment expectations versus outcomes among orthognathic surgery patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1991; 6:247–255.

67. Ouellette, PL. Psychological ramifications of facial change in relation to orthodontic treatment and orthognathic surgery. J Oral Surg. 1978; 36:787.

68. Padwa, BL, Evans, CA, Pillemer, FC. Psychosocial adjustment in children with hemifacial microsomia and other craniofacial deformities. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1991; 28:354.

69. Patel PK, Kapp-Simon KA: Orthognathic surgery in adolescence: the patient’s perspective [abstract]. American Association of Plastic Surgeons 83rd Annual Meeting. Chicago, 2004.

70. Pavone, I, Rispoli, A, Acocella, A, et al. Psychological impact of self-image dissatisfaction after orthognathic surgery: a case report. World J Orthod. 2005; 6:141.

71. Pertschuk, MJ, Whitaker, LA. Psychosocial adjustment and craniofacial malformations in childhood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985; 75:177.

72. Peter, JP, Chinsky, RR. Sociological aspects of cleft palate adults: I. Marriage. Cleft Palate J. 1974; 11:295–309.

73. Peterson, LJ, Topazian, RG. The preoperative interview and psychological evaluation of the orthognathic surgery patient. J Oral Surg. 1974; 32:583.

74. Phillips, C, Hill, BJ, Cannac, C. The influence of video imaging on patients’ perceptions and expectations. Angle Orthod. 1995; 65:263–270.

75. Phillips, C, Broder, HL, Bennett, ME. Dentofacial disharmony: motivations for seeking treatment. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1997; 12:7.

76. Phillips, C, Bennett, ME, Broder, HL. Dentofacial disharmony: psychological status of patient seeking a treatment consultation. Angle Orthod. 1998; 68:547–566.

77. Phillips, C, Kiyak, HA, Bloomquist, D, et al. Perceptions of recovery and satisfaction in the short term after orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004; 62:535.

78. Phillips, J, Whitaker, LA. The social effects of craniofacial deformity and its correction. Cleft Palate J. 1979; 16:7.

79. Pillemer, FG, Cook, KV. The psychosocial adjustment of pediatric craniofacial patients after surgery. Cleft Palate J. 1989; 26:201.

80. Pope, AW, Speltz, ML. Research on psychosocial issues of children with craniofacial anomalies: Progress and challenges. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997; 34:371.

81. Pope, AW, Ward, J. Self-perceived facial appearance and psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with craniofacial anomalies. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1997; 34:396.

82. Posnick, JC, Wallace, J. Complex orthognathic surgery assessment of patient satisfaction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008; 66:934.

83. Proothi, M, Drew, SJ, Sachs, SS. Motivating factors for patients undergoing orthognathic surgery evaluation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 68:1555–1559.

84. Ramstad, T, Ottem, E, Shaw, WC. Psychological adjustment in Norwegian adults who had undergone standardized treatment of complete cleft lip and palate: I. Education, employment and marriage. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1995; 29:251–257.

85. Rispoli, C, Acocella, A, Pavone, I, et al. Psychoemotional assessment changes in patients treated with orthognathic surgery: pre- and postsurgery report. World J Orthod. 2004; 5:48.

86. Rivera, SM, Hatch, JP, Dolce, C, et al. Patients’ own reasons and patient-perceived recommendations for orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000; 18:134.

87. Robinson, E, Rumsey, N, Partridge, J. An evaluation of the impact of social interaction skills training for facially disfigured people. Br J Plast Surg. 1996; 49:281–289.

88. Sarver, DM, Johnston, MW, Matukas, VJ. Video imaging for planning and counseling in orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988; 46:939–945.

89. Sarwer, DB, Bartlett, SP, Whitaker, LA, et al. Adult psychological functioning of individuals born with craniofacial anomalies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999; 103:412–418.

90. Scott, AA, Hatch, JP, Rugh, JD, et al. Psychosocial predictors of satisfaction among orthognathic surgery patients. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 2000; 15:7–15.

91. Secord, PF, Jourard, SM. The appraisal of body cathexis: body cathexis and the self. J Consult Psychol. 1953; 17:343–347.

92. Shisslak, CM, Crago, M, Estes, LS. The spectrum of eating disorders. Int J Eating Disord. 1995; 18:209.

93. Sinko, K, Jagsch, R, Prechtl, V, et al. Evaluation of esthetic, functional, and quality of life outcome in adult cleft lip and palate patients. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2005; 42:355–361.

94. Slade, GD, Spencer, AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health. 1994; 11:3.

95. Slade, GD. Assessing change in quality of life using the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998; 26:52.

96. Stewart, TD, Sexton, J. Depression: a possible complication of orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987; 45:847.

97. Stirling, J, Latchford, G, Morris, DO, et al. Elective orthognathic treatment decision making: a survey of patient reasons and experiences. J Orthod. 2007; 34:114.

98. Travess, HC, Newton, JT, Sandy, JR, et al. The development of a patient-centered measure of the process and outcome of combined orthodontic and orthognathic treatment. J Orthod. 2004; 31:220.

99. Upton, PM, Sadowsky, PL, Sarver, DM, et al. Evaluation of video imaging prediction in combined maxillary and mandibular orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997; 112:656.

100. Versnel, SL, Plomp, RG, Passchier, J, et al. Long-term psychological functioning of adults with severe congenital facial disfigurement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012; 129:110–117.

101. Wictorin, L, Hillerstrom, K, Sorensen, S. Biological and psycho-social factors in patients with malformations of the jaws. I. A study of 95 patients prior to treatment. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969; 3:138–143.

102. Williams, AC, Shah, H, Sandy, JR, et al. Patients’ motivations for treatment and their experiences of orthodontic preparation for orthognathic surgery. J Orthod. 2005; 32:191.

103. Williams, DM, Bentley, R, Cobourne, MT, et al. Psychological characteristics of women who require orthognathic surgery: comparison with untreated controls. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 47:191.

104. Wilmot, JJ, Barber, HD, Chou, DG, et al. Associations between severity of dentofacial deformity and motivation for orthodontic-orthognathic surgery treatment. Angle Orthod. 1993; 63:283.

105. Zhou, Y, Hagg, U, Rabie, AB. Severity of dentofacial deformity, the motivations and the outcome of surgery in skeletal Class III patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2002; 115:1031.