Psychosocial Aspects of Critical Care

ELIZABETH A. HENNEMAN, RN, PhD, CCNS and JAN MARIE BELDEN, MSN, APRN, BC, FNP (Contributor for content related to pain)

SYSTEMWIDE ELEMENTS

1. Scope of critical care nursing practice

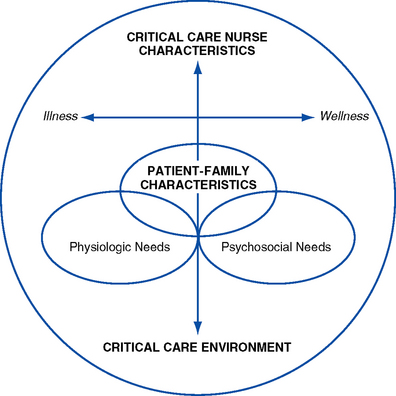

a. “The scope of practice for acute and critical care nursing is defined by the dynamic interaction of the acutely and critically ill patient, the acute or critical care nurse and the health care environment” (American Association of Critical-Care Nurses [AACN], 2000, p. 2) (Figure 10-1)

b. Critical illness is a crisis for both the patient and family members. This crisis situation can present numerous, oftentimes complex psychosocial issues and problems that require the expertise of the critical care nurse working collaboratively with the multidisciplinary team. The crisis of a critical illness may be superimposed on other chronic stressors (e.g., addiction).

c. Needs or characteristics of the patient and family influence and drive the characteristics or competencies of the critical care nurse (AACN, 2003)

d. Challenges of meeting psychosocial needs

i. Other conflicting priorities such as addressing the physiologic instability of the patient may preclude or inhibit nurses from meeting the psychosocial needs of the patient and family

ii. Psychosocial needs often involve family members (an aspect unique to psychosocial needs in contrast to physiologic needs); for example, issues such as grief and loss, and powerlessness may pertain more to the family than to the patient in some situations (e.g., brain-dead patient)

iii. Value systems in critical care units often emphasize performing nursing tasks over attending to the psychosocial needs of the patient and family

iv. Meeting psychosocial needs demands a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to care

v. Critical care environment is often a barrier to effectively meeting psychosocial needs

vi. Growing evidence supports an interrelationship between psychosocial and physiologic problems (e.g., stress and immunity)

i. Critically ill patients share some common, predicable psychosocial needs (e.g., the need for reassurance and support)

ii. Specific patient psychosocial needs vary depending on patient and family characteristics and the patient’s status on the health-to-illness continuum

iii. The more compromised the patient, the more complex the patient’s needs

iv. Critically ill patients’ psychosocial needs are based on patient characteristics, including resiliency, vulnerability, stability, complexity, resource availability, participation in care and decision making, and the predictability of the illness (AACN, 2003; Hardin and Kaplow, 2005)

v. Patient characteristics and needs influence family members’ needs and psychosocial issues

(a) Traditional: “A group of two or more people who reside together and who are related by birth, marriage, or adoption” (US Bureau of the Census, 2000)

(b) Contemporary: “Group of people who love and care for each other” (Seligmann, 1990)

ii. Families of critically ill patients share a variety of predictable psychosocial needs

iii. Specific psychosocial needs of family members vary depending on patient characteristics, family characteristics, and the patient’s status on the health-to-illness continuum (e.g., cultural diversity issues)

iv. Predicable needs of family members of critically ill patients include the following:

i. Critical care nurse characteristics influence the extent to which patient and family psychosocial needs are met

ii. Continuum of nursing characteristics includes clinical judgment, advocacy and moral agency, caring practices, collaboration, systems thinking, response to diversity, clinical inquiry, and facilitation of learning (Hardin and Kaplow, 2005)

i. Members of the critical care team include the nurse, physician, respiratory therapist, social worker, clergy, physical therapist, occupational and speech therapist, others as needed

ii. Psychosocial needs of the patient and family are met through the collaborative efforts of a multidisciplinary team; each member brings a unique perspective and specific expertise to the shared plan of care and patient goals

i. Critical care environment (interaction among elements—hence complexity)

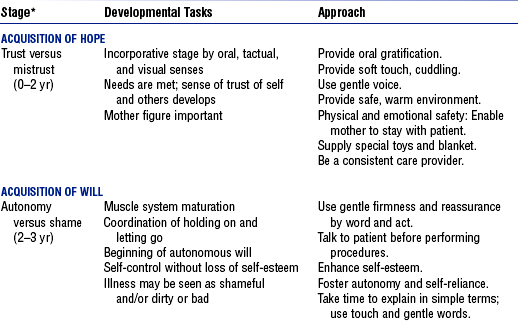

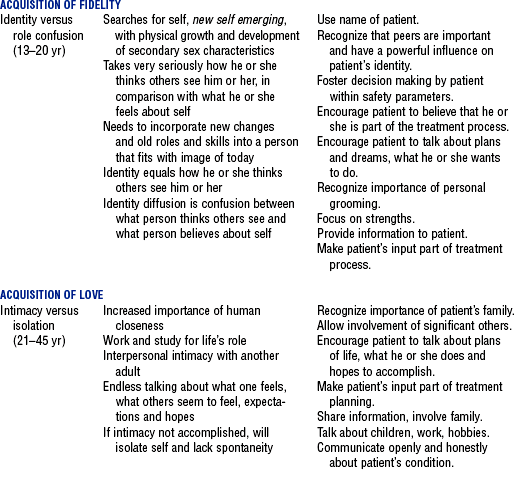

i. Patients and family members come to critical care units at all phases of the life cycle

ii. Growth and development of the patient and family members influence psychosocial needs, response to critical illness, and behaviors (e.g., body image changes may present serious psychologic stressors to young adults)

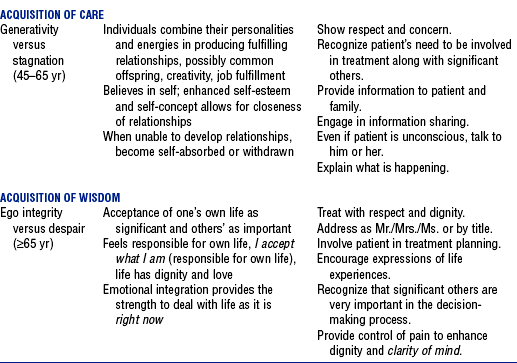

iii. Erikson’s eight stages of the life cycle: See Table 10-1

i. Maslow categorized needs in terms of a hierarchy

ii. Basic needs must be satisfied before higher-level needs can be met

iii. Needs change throughout the life cycle

iv. Critical illness may require refocusing on the achievement of basic needs

(a) Derived from general system theory—a method of viewing systems that are composed of related parts that interact together as a whole

(b) Can be used by critical care nurses to understand family cultural patterns and dynamics, including communication patterns, power, economics, and interaction. Also helps give insight into dysfunctional family relationships (Satir, 1967).

(a) Groups of individuals bonded together by their interests

(b) Community whose members nurture and support one another

(c) Members have a set of rules, roles, power structure, forms of communication, and styles of problem solving that allow tasks to be accomplished effectively

(d) Critical illness alters rules, roles, power, and so on, in the family, which creates stress and the need for adaptation to a new environment and situation

i. Can directly affect the ability to meet a patient’s needs, including the need for rest and sleep (e.g., lack of doors on patient rooms, fluorescent overbed lighting, etc.).

ii. Staff awareness and behaviors also can have a profound effect on modifying environmental influences that affect the patient.

iii. Unusual patterns of light and noise, together with the constant activity of a critical care unit, alter the patient’s biologic rhythms and may negatively affect patient outcomes (Jastremski and Harvey, 1998)

iv. Environmental factors may lead to sensory overstimulation or sensory deprivation

(a) Noise: Sources of noise include staff conversations, alarms, and equipment. Critically ill patients have reported the sound of human voices outside the room to be the most disturbing sound (Topf, Bookman, and Armand, 1996). Adverse effects of noise include increased adrenaline levels, diminished immune function, and decreased pain tolerance (Grumet, 1993; Pope, 1995).

v. Strategies for creating a healing environment: See Box 10-1

i. Definition: Condition that exists in an organism when it encounters stimuli (Selye, 1974)

ii. Critical illness is a stressful situation. Directed interventions by the nurse can lessen stress and/or the impact of stress on the patient and family. Nursing presence and the anticipation of patient needs have been reported to be associated with less stressful critical care experiences (Holland, Cason, and Prater, 1997; Pettigrew, 1990).

iii. Selye (1974) identified two types of stress

(a) Eustress: Condition that exists in an organism when it meets with nonthreatening stimuli

(b) Distress: Condition that exists in an organism when it meets with noxious stimuli

iv. Common psychologic stressors for critically ill patients and their families

(a) Noxious psychosocial stimuli can overwhelm the body’s compensatory ability to maintain homeostasis and can elicit a stress response

(b) Major neural response to a stressful stimulus is activation of the sympathetic nervous system

(c) Relationship between psychologic stress and health: Psychoneuroimmunologic research has identified a relationship between stress and immune function (i.e., an increased stress response is associated with decreased immunity) (Caine, 2003)

Patient and Family Psychosocial Assessment

i. Identify preexisting psychiatric, psychologic, and social problems

ii. Identify preillness coping mechanisms

iii. Identify sources of support (e.g., family, friends, spiritual support, pets)

iv. Identify patient proxy, living will, durable power of attorney, and so on

b. Family history: Family assessment data obtained on admission or as soon as possible

i. Health care proxy or family spokesperson

ii. Contact information (e.g., home and cell phone numbers, pager numbers)

iii. Diversity issues (culture, language, etc.) that affect the patient and family

vi. Support systems (family, friends, church group, other spiritual support)

vii. Special family needs (e.g., young children, handicaps, etc.)

viii. Family concerns regarding this hospitalization

ix. Best time for family to visit the patient

x. Preferred method of meeting and communicating with intensive care unit (ICU) team members (e.g., participation in scheduled ICU rounds, scheduled evening meetings, phone calls)

2. Nursing examination of patient

b. Cognitive assessment (e.g., ability to concentrate, level of judgment, presence of confusion)

c. Behavioral assessment (sleep patterns, level of agitation, interaction with family and staff)

d. Review of findings from other diagnostic studies (e.g., computed tomographic [CT] scan, electroencephalogram [EEG], etc.)

3. Appraisal of patient characteristics: Almost all patients with a critical illness experience some psychosocial issues during the course of their illness. However, each patient and family is unique and brings a unique set of characteristics to the care situation (Hardin and Kaplow, 2005). Examples of characteristics of patients and family that the nurses need to assess include the following:

i. Level 1—Minimally resilient: A 52-year-old divorced woman who has attempted suicide via drug overdose on three previous occasions is admitted with a nonlethal self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head

ii. Level 3—Moderately resilient: A 23-year-old man with a 9-year history of “problem drinking,” stabilized after chest trauma suffered in an alcohol-related automobile accident, is being prepared for transfer to a military hospital where he will receive extended treatment for alcohol abuse

iii. Level 5—Highly resilient: A healthy 21-year-old female college student with a 3.9 grade point average comes to the emergency department exhibiting multiple abrasions and unruly, belligerent, and delirious behavior after attending her first “spring breakout celebration,” which included drinking, some drug experimenting, and falling off the roof of a moving car

i. Level 1—Highly vulnerable: A malnourished 9-year-old child who has been a victim of child abuse since birth is recovering from his most recent “fall down the stairs” and is scheduled for discharge home the next day

ii. Level 3—Moderately vulnerable: An extremely overweight 37-year-old woman admits to feeling “even more depressed” following her unsuccessful suicide attempt. Numerous diets, pills, and plans have not worked, and her primary physician relates that she does not meet the criteria for surgical treatment of morbid obesity.

iii. Level 5—Minimally vulnerable: A 44-year-old single father, admitted for monitoring overnight subsequent to an automobile crash in which he was cited for aggressive driving, relates that since his recent divorce, he occasionally has had episodes when his anger quickly escalates to violent behaviors. He fears “taking it out” on his two sons.

i. Level 1—Minimally stable: A 65-year-old woman develops acute respiratory distress syndrome following the ingestion of an alkali solution during an attempted suicide

ii. Level 3—Moderately stable: A 50-year-old male with a history of drinking four beers a day is admitted to the ICU for an initial episode of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to a duodenal ulcer. He is receiving benzodiazepines to prevent delirium tremens from acute alcohol withdrawal.

iii. Level 5—Highly stable: A 25-year-old female is admitted to the ICU from the emergency department, to which she was brought by friends who could not wake her after a night of heavy drinking. She is now awake and alert.

i. Level 1—Highly complex: An 89-year-old man is experiencing liver failure secondary to the ingestion of 200 acetaminophen tablets following the death of his wife. Patient has multiple medical problems, including lung cancer. He stated in his suicide note that he “is tired” and wants to be with his wife. Family is adamant that everything be done to save his life.

ii. Level 3—Moderately complex: A 60-year-old patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis develops acute respiratory failure while in the ICU. Patient has already stated he does not desire mechanical ventilation to prolong life. Family is supportive of the patient’s wishes.

iii. Level 5—Minimally complex: A 50-year-old woman in the ICU for the management of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory use develops delirium after receiving sedatives

i. Level 1—Few resources: A 40-year-old homeless man is admitted to the ICU after attempted suicide by gunshot to the head. No patient identification is available.

ii. Level 3—Moderate resources: An 83-year-old woman is admitted from a local nursing home to the ICU with possible urosepsis. Patient’s family has been paying out of pocket for the nursing home but says “the money is almost gone.”

iii. Level 5—Many resources: A 60-year-old computer executive develops delirium tremens 4 days after undergoing elective hip surgery. Family is very supportive and confident the patient would be concerned if he realized how his drinking (three to four glasses of wine per day) had affected him. Patient has excellent insurance coverage for both inpatient care and outpatient substance abuse treatment.

i. Level 1—No participation: An 85-year-old male patient underwent a complicated aortic aneurysm repair 3 days earlier. Patient has a 10-year history of dementia and is now experiencing delirium. He is intubated and unable to communicate with the staff.

ii. Level 3—Moderate level of participation: A 35-year-old man, who sustained a head injury after falling out of a tree while intoxicated, is now regaining consciousness and is asking for some water

iii. Level 5—Full participation: A 70-year-old man is admitted to the ICU following extensive abdominal surgery. He asks the nurse for more pain medication so that he can “sit up more and take some deep breaths” like his preoperative instructions directed.

g. Participation in decision making

i. Level 1—No participation: The mother of an 18-year-old brain-dead patient collapses when approached about organ donation. She asks the patient’s doctor to make all the necessary decisions.

ii. Level 3—Moderate level of participation: The wife of a 67-year-old man who requires a tracheostomy for long-term airway management following a suicide attempt requests multiple consults from other pulmonary services

iii. Level 5—Full participation: A 65-year-old patient with cancer and chronic pain asks to be removed from the ventilator and be “allowed to die with dignity”

i. Level 1—Not predictable: A 75-year-old woman with ovarian cancer is admitted after ingesting one-half of a bottle of acetaminophen to “stop the pain”

ii. Level 3—Moderately predictable: A 60-year-old patent with acute respiratory failure develops delirium secondary to a combination of hypoxemia and electrolyte imbalances

iii. Level 5—Highly predictable: A 20-year-old patient is admitted with altered consciousness after drinking at a college fraternity party

Psychosocial Care Issues

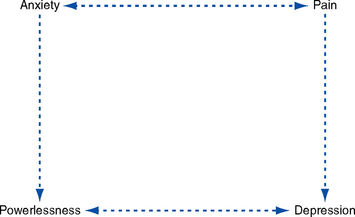

1. Interdependence—Many of the psychosocial issues and concerns of the critically ill patient are interdependent. For example, inadequately managed pain may lead to feelings of powerlessness, anxiety, and depression that, in turn, heighten the patient’s perception of pain (Figure 10-2).

i. Perceived lack of control over the outcome of a specific situation. The ability of an event to engender a sense of powerlessness is influenced by the individual’s self-esteem and self-concept and where the individual is in the life cycle.

ii. Critically ill patients lose their ability to control even the most basic of functions, including the ability to communicate, to breath on their own, and to control bladder and bowel function. Depending on the philosophy and organization of the critical care environment, they may also lose the ability to participate in decision making about their own health care and future.

i. Patient communicates needs and wishes verbally or nonverbally

ii. Patient (and family as appropriate) participates in decision making regarding the plan of care

iii. Patient and family members do not demonstrate signs of dysfunction associated with powerlessness, such as the following:

iv. Patient participates in decision making regarding daily care activities (e.g., timing of bath, sleep, visiting hours)

c. Collaborating professionals on health care team

i. Promote patient-nurse communication

(a) This intervention presents significant challenges, particularly if the patient is intubated or speaks a language other than English (or the predominant language at the facility)

(b) Methods of communication should be based on patient preferences and abilities. Common communication techniques for use with intubated patients include lip reading, picture or alphabet boards, pen or pencil and paper, and computer.

(c) Utilize available interpreter services for non–English speaking patients and family members

(d) Enlist help from family members and volunteers in the communication process

ii. Involve the patient and family in the care planning process and decision making

(a) Ask the patient (or health care proxy) what level of involvement he or she would like in the care planning process

(b) Encourage the patient and family members to keep a record of questions and concerns

(c) Provide the patient, proxy, or a family member with daily (or more frequent) updates regarding the patient’s status and care plan

iii. Encourage the patient and family members to meet with spiritual support persons if they would find this helpful

iv. Prepare the patient for procedures: Explain what will be happening, when it will happen, and how the patient will be affected

e. Evaluation of patient care: Patient and family are active participants in care planning and delivery (to the extent possible)

a. Description of problem: Sleep deprivation in the critically ill patient involves a decrease in the amount, consistency, and/or quality of sleep that occurs in a 24-hour period. Sleep fragmentation occurs when the patient fails to complete a 90-minute average sleep cycle that includes both rapid eye movement and non–rapid eye movement sleep (Gawlinski and Hamwi, 1999).

i. Patient has at least two 90-minute periods of sleep in a 24-hour period

ii. Patient states that he or she feels rested

iii. Patient does not demonstrate signs and symptoms of sleep deprivation, including the following:

c. Collaborating professionals on health care team

i. Attempt to provide at least two 90-minute periods of uninterrupted sleep in a 24-hour period

ii. Cluster activities so that the patient is allowed periods of rest

iii. Prioritize activities to allow a stable patient to have periods without unnecessary, frequent assessments

iv. Decrease the noise level to promote sleep

v. Decrease overhead lighting to promote sleep

vi. Provide adequate pain relief

vii. Teach the patient and family relaxation techniques to promote rest and sleep

viii. Administer pharmacologic agents as needed to promote sleep (e.g., benzodiazepines, diphenhydramine). Note: Long-term use of benzodiazepines can abolish stage IV sleep.

ix. Consult with a pharmacist regarding the best drug choices for promoting sleep, particularly for high-risk populations such as the elderly

a. Description of problem: The grief reaction is the emotional response to a loss in which something valued is changed or altered so that it no longer has its previously valued traits (Gawlinski and Hamwi, 1999)

i. Grief can be experienced during a critical illness by both the patient and family members

ii. Grief may result from loss (or potential loss) of health, body image, role, and financial security

iii. Family members experience grief related to a patient’s death or in anticipation of death or potential death

iv. Degree of grief experienced is related to the meaning of the loss to the individual, the adequacy of coping responses, and the availability of support systems

v. Expressions of grief have wide variation and are culturally determined

i. Patient and family express feelings of grief and loss (if they choose)

ii. Patient and family are able to state the prognosis and current plan of care

c. Collaborating professionals on health care team

i. Appreciate cultural variation in expressions of grief

ii. Allow the patient and family members to express grief in their own way

iii. Provide privacy for family members and patients

iv. Provide ongoing, honest information to the patient and family regarding the patient’s illness and expected recovery

v. Provide the patient and family with teaching regarding the normal grief response

e. Evaluation of patient care: Patient and family express grief in a culturally appropriate way

SPECIFIC PATIENT HEALTH PROBLEMS

1. Definition: Anxiety is the apprehensive anticipation of future danger or misfortune accompanied by a feeling of dysphoria or somatic symptoms of tension. Focus of anticipated danger may be internal or external (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000).

2. Etiology and risk factors: Results from multiple sources in the ICU, including the following:

a. Unstable physiologic status (e.g., hypoxemia with shortness of breath)

e. Separation from family and support system

f. Underlying psychiatric disorder (including panic disorders, phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder)

3. Signs and symptoms: See Box 10-2

a. When behavioral manifestations of anxiety are present, possible physiologic causes (e.g., hypoxemia and hypoglycemia) must be ruled out

b. Toxicologic screen: To assess for possible drug-induced anxiety

c. Mental status examination: Findings may be abnormal with severe anxiety

5. Collaborative diagnoses of patient needs: Minimize anxiety for the patient and family by preparing them for potentially anxiety-producing situations

a. Patient does not demonstrate signs or symptoms of anxiety (e.g., no tachypnea, tachycardia, muscle tension)

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: With reassurance, support, and pharmacologic therapy as needed, anxiety can be minimized

(1) Reassure the patient and give explanations about the patient’s condition and treatment plan

(2) Ask the patient to discuss fears and worries

(3) Assure the patient that adequate sedation and pain medication will be provided during painful procedures

(4) Allow family members to stay with the patient as much as possible to provide support

(a) Teach the patient and family methods of anxiety reduction (e.g., imagery, distraction)

(b) Patient may require post-ICU follow-up (psychiatric and/or social services) for unresolved anxiety issues

(c) Patient may require follow-up teaching regarding pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions to treat anxiety

Pain

a. Pain is an individual, subjective, and complex biopsychosocial process whose existence cannot be proved or disproved. Unrelieved pain is a major psychologic and physiologic stressor for patients.

b. Pain is “whatever the person says it is, existing whenever he says it does” (McCaffery, 1968)

c. Pain is “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience” (Mersky, 1979)

i. Amount of tissue damage is not the only predictor of when and how pain is experienced (Koestler and Doleys, 2002)

ii. Other factors influence the response to the cognitive integration of pain (e.g., age, gender, culture, beliefs, mood, previous pain experiences, current diagnosis and situation, amount of perceived control over the situation)

iii. Negative impact of pain on one’s quality of life can include suffering, fear, anxiety, depression, and hopelessness (Cullen, Greiner, Titler, et al, 2001; Graf and Puntillo, 2003; Hamill-Ruth and Marohn, 1999)

d. In critical care patient populations, pain is often undertreated and represents one of patients’ greatest worries (Lang, 1999)

i. Surgical events (e.g., incisions; presence of drains, tubes, orthopedic hardware)

ii. Traumatic injuries (e.g., fractures, lacerations)

iii. Medical conditions (e.g., pancreatitis, ulcerative colitis, migraine headache)

iv. Psychologic conditions (e.g., anxiety), which can increase pain perception, prolong the pain experience, and lower the pain threshold (Koestler and Doleys, 2002)

b. Procedures (e.g., turning; suctioning; placement or removal of catheters, tubes, or drains; paracentesis)

d. Preexisting chronic pain conditions

i. Musculoskeletal conditions (e.g., arthritis, low back pain, fibromyalgia)

ii. Other conditions (e.g., cancer, stroke, diabetic neuropathy)

e. Pain can also be perceived without the current presence of a physiologically unpleasant stimulus (Koestler and Doleys, 2002)

a. See Chapter 4 for physiologic aspects of pain

b. Most reliable indicator of pain is the patient’s self report (Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel, 1992)

c. Other important points related to manifestations of pain include the following:

i. Patients in pain often demonstrate one or more behavioral signs or indicators of pain intensity (see Table 4-22)

ii. When patients are unable to respond or self-report pain, behavioral indicators may be used (Pasero, 2003). Due to the individuality of pain expression, these indicators may be absent despite the presence of severe pain, which may cause clinicians to conclude erroneously that pain is not present (American Pain Society [APS], 2003).

iii. When conditions known to be painful exist, assume that pain is present and proceed with appropriate treatment (APS, 2003; Graf and Puntillo, 2003)

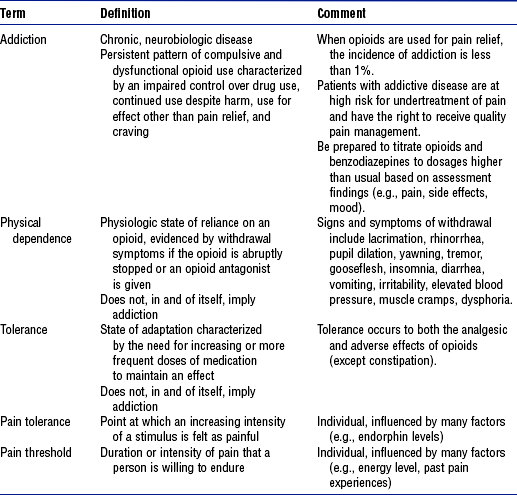

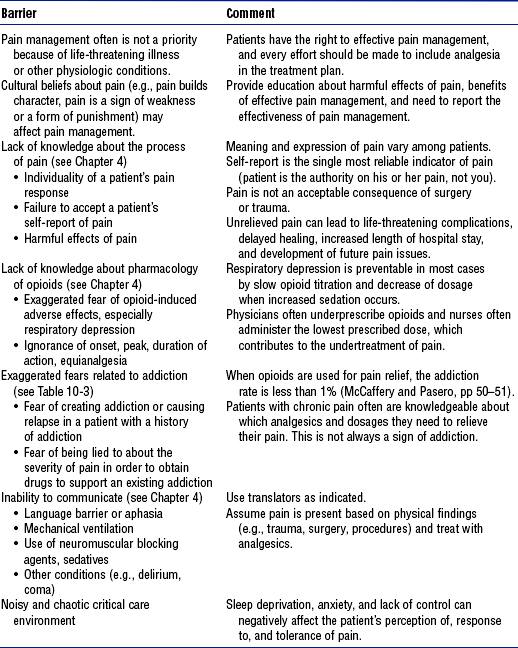

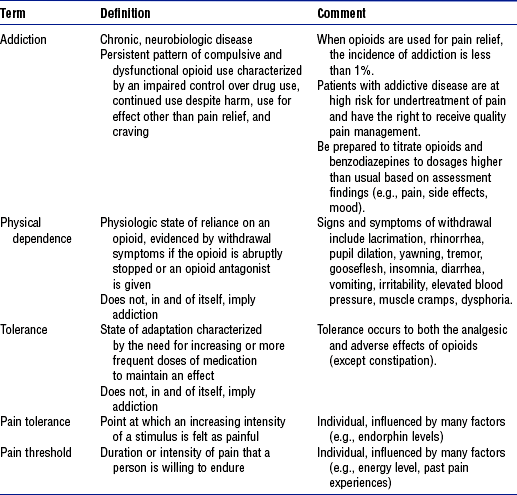

iv. Several barriers and misconceptions about pain hinder effective pain management (Table 10-2), including the clinician’s personal values and beliefs, and confusion about addiction, tolerance, and physical dependence with regard to pain medications. See Table 10-3 for distinctions in these terms as they relate to pain and opioid use.

TABLE 10-3

Definitions Related to the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Pain

Data and definitions compiled from American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine: Consensus document: Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain, Glenview, Ill, 2001, American Academy of Pain Medicine. Available at http://www.asam.org/ppol/paindef.htm; American Society of Pain Management Nurses: ASPMN position statement: pain management in patients with addictive disease, Pensacola, Fla, 2002, Author; and McCaffery M, Pasero C: Pain: clinical manual, ed 2, St Louis, 1999, Mosby. American Academy of Pain Medicine

d. Practitioners must accept and respond to patient reports of pain

e. Decrease in or elimination of a pain behavior following an analgesia intervention can indicate a reduction in pain and reflect an ongoing need for analgesia (Hamill-Ruth and Marohn, 1999; McCaffery and Pasero, 1999)

a. “Pain is described by the person experiencing it; it doesn’t have to be diagnosed any other way” (Puntillo, 1995)

b. Diagnostic studies may supplement, but should not replace, a comprehensive physical examination and history (National Pharmaceutical Council, 2001)

c. Diagnostic studies can help to accurately identify the causes for pain; however, the absence of positive study findings should not be used to deny the existence of pain

d. While diagnostic studies are in progress, treatment of pain should be initiated. It is rarely justified to defer analgesia until a diagnosis is made (APS, 2003; Pace and Burke, 1996).

a. Pain, including procedural pain, is consistently controlled at or below the patient’s stated comfort level (e.g., a pain score of 2 to 3 on a scale of 0 to 10)

b. In a patient unable to provide a self-report of pain, there is a marked decrease or absence of pain behaviors following pharmacologic intervention

c. Patient demonstrates a decrease in anxiety and other psychologic effects of unrelieved pain

d. Patient is able to comfortably perform or participate in activities necessary for recovery

e. Patient experiences increased periods of uninterrupted sleep

f. Medication adverse effects are avoided or managed

g. Length of hospital stay is not extended because of poorly managed pain

a. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO, 2004) pain management standards include the following:

i. “Patients have the right to pain management” (RI.2.160)

ii. “When pain is identified, the patient is assessed and treated by the hospital or referred for treatment” (PC.8.10)

b. Anticipated patient trajectory

(a) Perform thorough history taking (including a pain history), physical examination, and pain assessment

(b) Identify the underlying cause whenever possible

(c) Identify any previously effective methods of coping with and relieving pain

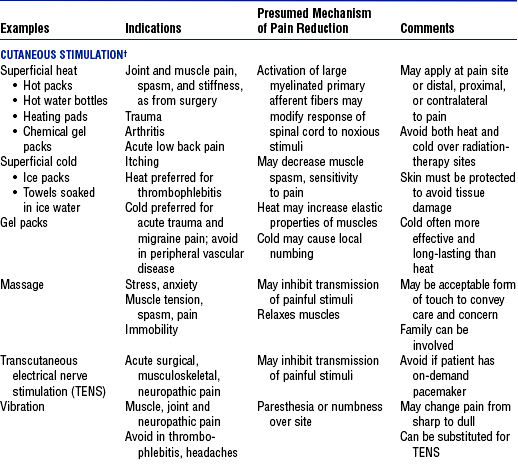

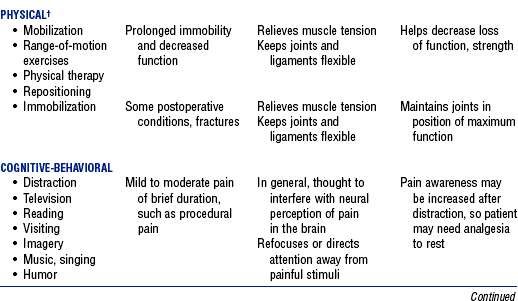

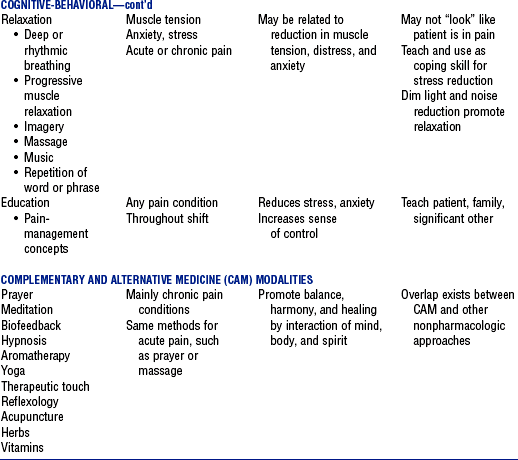

(1) May be used to supplement, but not replace, analgesic medications. Table 10-4 provides an overview of these therapies.

TABLE 10-4

Nonpharmacologic Approaches to Pain Management in the Critically Ill Patient*

*In most clinical situations, these approaches should be used in addition to analgesics.

(2) There is a lack of conclusive scientific evidence to support the efficacy of their use for pain management

b) Many do not relieve pain; some may only make pain more tolerable for brief intervals

c) Patients must be willing and physically and mentally able to try them

(3) No universally accepted categorizations or definitions of these methods exist. Broad categories include the following:

(4) Use of these methods in the critically ill patient is limited due to the severity of the patient’s illness and other demands on the nurse’s time

iii. Discharge planning: Patient and family teaching regarding the following:

(a) Appropriate use of pain scales or other methods to be used to assess pain

(b) Effective pain management concepts and options (e.g., pain medications and the difference between addiction, physical dependence, and tolerance)

(c) Pain management as an important part of patient care

(d) Responsibility of the patient to report ineffective pain relief and concerns regarding the pain management plan

iv. Useful pain management resources: See pain section in the reference list

Delirium (Acute Confusional State)

1. Definition: Clinical state associated with a disturbance of consciousness that is accompanied by a change in cognition that cannot be accounted for by a preexisting or evolving dementia. Delirium develops over a short time (hours to days) and fluctuates during the course of a day (APA, 2000). Delirium is often a temporary condition.

b. Delirium due to a general medical condition

iv. Heart, kidney, liver failure

v. Hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism

vii. Cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack

x. Electrolyte imbalances (hyperkalemia, hypokalemia)

xi. Hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia

c. Substance-induced delirium (due to a medication, toxin exposure, drug abuse)

iii. Disorientation to person, place, time

iv. Confusion over daily events

v. Hallucinations (visual are more common)

vi. Abnormal results on a mental status examination (i.e., Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination)

4. Diagnostic study findings: Dependent on the underlying problem (e.g., may have abnormal electrolyte levels, CT scan, etc.)

5. Collaborative diagnoses of patient needs

a. Assess for possible factors that could contribute to delirium

b. Decrease the use of medications that could contribute to delirium

a. Patient is oriented to person, time and place

b. Patient does not demonstrate signs or symptoms of anxiety, fear, and confusion

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: With treatment of the underlying cause of delirium, the problem can be managed and eliminated

(1) Assess for delirium (e.g., Confusion Assessment Method–ICU) (Inouye, Van Dyke, Alessi, 1990; Truman and Ely, 2003)

(2) Provide for adequate rest and sleep

(3) Review medication list with the physician and discontinue suspect medications

(4) Monitor and manage electrolyte and acid-base disorders

(5) Consult a psychiatrist if delirium does not resolve with standard management

(6) Use restraints only as needed for patient safety

(7) Explain to family members the nature of delirium and why it occurs. Stress the temporary nature of the condition in hospitalized patients.

(8) Give family members updates on patient management and progress (e.g., findings related to the underlying cause of the delirium)

(9) Reassure the family that the patient is not in control or responsible for his or her behaviors

(b) Pharmacologic: Avoid additional drugs unless needed for patient, family, or staff safety

Depression

1. Definition: Mood state characterized by feeling of sadness, lowered self-esteem, and pessimistic thinking and guilt (Gawlinski and Hamwi, 1999). Depressive episodes and depressive disorders are psychiatric diagnoses given to patients based on specific criteria (e.g., etiology, length of depression) (APA, 2000).

a. Incidence in the medically ill ranges from 6% to 72% (APA, 2000)

(b) Fear and anxiety regarding the illness and the outcome of the illness

ii. Cognitive: Patient’s beliefs (thoughts such as “It’s all my fault”) may lead to depression

a. Diagnosis based on history and clinical examination (i.e., cognitive and behavioral changes)

b. Diagnostic test results may be abnormal if there is an underlying physiologic problem contributing to the depression (e.g., digoxin toxicity)

c. Mini-mental status examination to rule out delirium (delirium may be confused with depression)

d. EEG: Sleep EEG abnormalities may be present in up to 90% of inpatients during a major depressive episode (APA, 2000)

5. Collaborative diagnoses of patient needs

a. Allow the patient to participate in goal setting with the ICU team

b. Treat manageable symptoms such as pain and anxiety that may contribute to depression

c. Review the plan of care with the patient and stress areas of improvement as appropriate

d. Allow the patient control over the environment as much as possible

e. Assist the patient in understanding the biochemical nature of depression (when appropriate)

a. Patient verbalizes concerns about his or her medical condition, treatment plan, and so on, that led to feelings of depression

b. Patient is able to describe the presumed cause and management of depression for his or her particular situation

c. Patient is able to describe his or her role in the plan of care

d. Patient sets realistic goals with the health care team regarding the plan of care

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: With counseling, ongoing support from family and friends, and, when indicated, pharmacologic therapy, patients with depression can resume and maintain normal lives

(1) Assist in performing a differential diagnosis: Grief reaction, mood disorder, organic brain syndrome, delirium, dementia, metabolic conditions presenting as depression (e.g., hypercapnia, metabolic acidosis, uremia)

(2) Discuss the treatment plan and progress with the patient—engage the patient in care planning as appropriate

(3) Discuss concerns over possible or actual depressed state

(4) Acknowledge that a depressed mood can be normal during or following a serious illness

(5) Provide a mechanism to increase social support (family support, social services)

(6) Attend to any suicidal ideation (is the patient a threat to self or others?)

(b) Pharmacologic: Antidepressants (e.g., tricyclics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors)

(a) Provide information to the patient and family about depression and available treatments

(b) Discuss pharmacologic therapy, including mode of action, benefits, and side effects

(c) Patient may require follow-up evaluation and teaching on pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for depression

Alcohol Withdrawal

1. Definition: Presence of a characteristic withdrawal syndrome that develops after the cessation of (or reduction in) heavy and prolonged alcohol use

2. Etiology and risk factors: Abrupt cessation of alcohol use in persons with a physical dependence

3. Signs and symptoms (12 to 48 hours after cessation of alcohol intake): Withdrawal syndrome includes two or more symptoms of autonomic hyperactivity (e.g., sweating, pulse >100 beats/min, insomnia, agitation) (APA, 2000)

a. Mild to moderate dependency

b. Delirium tremens (48 to 72 hours after cessation of alcohol intake)

a. Blood alcohol level: Elevated on admission

b. Liver function studies: Values may be elevated

c. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA-Ar) (Sullivan, Sykora, Schneiderman, et al, 1989) or Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol DSM-IV version (CIWA-AD) (Sellers, Sullivan, and Somer, 1991) to quantify the severity of withdrawal and guide collaborative diagnoses of patient needs

a. Patient does not demonstrate signs or symptoms of withdrawal (e.g., seizures, agitation, irritability) that affect patient, family, and staff safety

b. Patient states negative effects of alcohol on body systems (e.g., liver failure)

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: With aggressive pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management, patients undergoing acute alcohol withdrawal should recover without incident. Life-long counseling and support (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous) is needed for patients with an alcohol addiction.

(a) Patient referral to Alcoholics Anonymous for current and future management

iii. Ethical issues: Staff may have ethical issues or conflicts caring for patients whose health problems they perceive to be “self-inflicted”

Aggression and Violence

1. Definition: Aggression is forceful physical or verbal behavior that may or may not cause harm to others. Violence is the ultimate maladaptive coping response and is the acting out of aggression that results in injury to others or destruction of property (Gawlinski and Hamwi, 1999).

2. Etiology and risk factors: Violence in the critical care setting may be triggered by the accumulation of stress in patients or family members who have feelings of desperation and who lack coping skills and/or resources to resolve a situation by other means. Aggression and violence can be present with the following:

a. Mental status examination: To help rule out organic brain disease

b. Laboratory tests: To rule out metabolic problems

c. Drug screens: May reveal toxic drug levels, high blood alcohol levels

5. Collaborative diagnoses of patient needs

a. Protect patient, family, and staff from injury

b. Provide the patient and family members with support and information early in the ICU stay

c. Attend to aggressive behavior rapidly and definitively

d. Be proactive in using appropriate resources (e.g., social services, security)

6. Goals of care: Patient does not demonstrate aggressive or violent behaviors toward self or others

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: With ongoing support and counseling, patients exhibiting aggressive and/or violent behaviors have the potential to modify these behaviors and live normal lives

(1) Review medication list and discontinue suspect medications

(2) Identify and remove other possible causes or stimuli that precipitate aggressive or violent behaviors (e.g., argumentative, challenging family members)

(3) Involve social service personnel early in the patient’s stay, particularly in high-risk situations (e.g., known alcohol abuse in family members)

a) Verbal, chemical, and physical restraints may be required to relieve symptoms and maintain safety

b) Use of physical restraints requires a plan, and explanation of their use to the patient and family, daily renewal of the restraint order, close monitoring, and use of alternative methods of restraint as appropriate

(5) Patient and family member issues

a) Speak in a calm, soft, noncondescending manner

b) Allow the patient and family member to ventilate verbally without interruption

c) Focus on the particular incident at hand

d) Place clear limits on what will and will not be tolerated—outline the consequences of aggressive or violent behavior

e) Do not attempt to educate the patient and family about aggression and violence during the aggressive or violent episode

Suicide

1. Definition: A suicide attempt is the actual implementation of a self-injurious act with the express purpose of ending one’s life (Keltner, Schwecke, and Bostrom, 2003). Patients coming to a critical care setting have often been unsuccessful in their suicide attempt and are admitted for actual or potential medical problems (e.g., respiratory depression, liver failure following acetaminophen overdose). A patient who has attempted suicide may be admitted to the ICU to determine if the person meets the criteria for brain death.

3. Signs and symptoms: May vary markedly depending on the type and extent of the injury present and the time that has elapsed since the injury

i. Altered level of consciousness and orientation

ii. Severe anxiety (if conscious)

b. Physiologic (related to the agent used in the suicide attempt, the extent of injury and the time that has elapsed)

a. Related to the method of attempted suicide

i. Elevated liver enzyme levels: Acetaminophen overdose

ii. Abnormal CT scan: Gunshot wound to the head

iii. Abnormal arterial blood gas levels

(a) Metabolic acidosis: Salicylate, methanol overdose

(b) Respiratory acidosis: Barbiturate, benzodiazepine, and/or opiate overdose

iv. Electrolyte abnormalities: Hyperkalemia with digitalis overdose

v. Abnormal coagulation results (increased international normalized ratio and prothrombin time): Warfarin overdose

5. Collaborative diagnoses of patient needs

a. Provide a safe environment for the patient, family, and staff

b. Demonstrate trust, respect, and acceptance of the patient

a. Patient discusses suicidal thoughts with health care team

b. Patient verbalizes the need for help

c. Patient verbalizes needs and concerns

d. Patient verbalizes positive feelings about self

7. Management of patient care (see Box 10-3 for more information related to the nursing care of the suicidal patient)

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: Outcomes for patients who have attempted suicide vary significantly depending on the mechanism and extent of injury. Many suicidal patients can live normal lives if they receive counseling and support.

i. Treatments (will be specific to the mechanism of injury)

(a) Stabilize the airway, breathing, and circulation

(b) Institute specific treatment related to toxin ingestion, wounds (e.g., gastric lavage for drug overdose when indicated). Consult the poison control center or POISINDEX® (Thomson Micromedex) when relevant.

(c) Assess the patient’s risk for future suicide attempts

(d) If the patient is at continued risk for a suicide attempt, provide for protection from injury (e.g., constant observation, restraints). See JCAHO standards for the use of physical restraints (http://www.JCAHO.org).

(e) Once the patient’s condition has stabilized, allow for opportunities to discuss the attempted suicide and the patient’s feelings (e.g., hopelessness, anger, shame, sadness) in a private setting

(f) Obtain a mental health consultation (patient’s private psychiatrist, or staff psychiatrist or advanced practice nurse)

(g) Facilitate visits from the patient/family support system (friends, clergy)

(h) Allow family members to verbalize their feelings and concerns related to the suicide or attempted suicide

(a) Varies depending on patient factors (e.g., physical and psychologic state) and family and social support systems

(b) Provide information on a 24-hour suicide prevention hotline

(c) Provide phone numbers and websites for illness-specific support ser-vices (e.g., http://www.americanheart.org; http://www.americancancersociety.org; http://www.multiplesclerosis.org)

iii. Ethical issues: Attempted assisted suicide by the patient and family in cases of terminal disease or unbearable chronic condition (see Chapter 1)

Dying Process and Death

1. Description: Process of dying in the critical care setting can take many forms. Patient may die suddenly as a result of the injury or condition, after a protracted illness, after the withdrawal of life support, or as a result of brain death.

a. Care of patients and family members during or following the dying process is heavily influenced by the circumstances surrounding the patient’s death

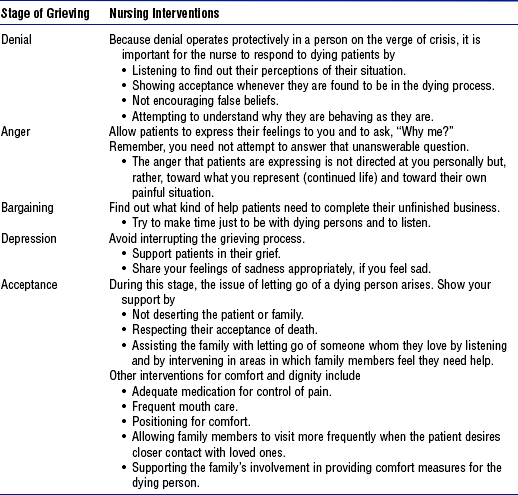

b. Kübler-Ross described five psychologic stages of the dying process (Table 10-5)

3. Diagnostic study findings: Most commonly used in the diagnosis of brain death. Studies include EEG, cerebral blood flow studies.

4. Collaborative diagnoses of patient needs

a. Ensure that the patient does not experience discomfort (pain, shortness of breath, etc.) or anxiety during the dying process

b. Ensure that family members’ needs to be with the patient, receive reassurance and support, and have hope for a peaceful death are met

a. Patient and family members openly discuss fears and concerns regarding the dying process

b. Patient rates pain as within the goal range (determined by the patient)

c. Patient does not complain of shortness of breath

d. Brain death: Family members recognize the brain-dead patient as legally dead and do not confuse brain death with a vegetative state

6. Management of patient care (see Table 10-5 for more information on caring for the dying patient)

a. Anticipated patient trajectory: A peaceful death, in the manner desired by the patient and family, is the expected outcome

(1) Ensure that do-not-resuscitate orders are written when appropriate

(2) Allow the patient and family members to discuss fears and concerns regarding the dying process

(3) Allow the patient and family members time to be alone (if desired)

(4) Use nonpharmacologic methods of pain relief (see Pain)

(5) Determine cultural preferences related to the dying process and postmortem care

(6) Assist the dying person and his or her family members to validate their feelings (e.g., anger, pain)

(7) Acknowledge the grieving that accompanies the dying process

(8) Help the patient and family to prepare for the dying process by describing possible symptoms and how they can be treated

(9) Explain the role of pain medication—to relieve pain versus hasten dying

(10) Determine the patient’s and family’s desires for spiritual support and assist in obtaining support (notify clergy, etc.)

(11) Assist with the withdrawal of life support (e.g., extubation); use guidelines for the withdrawal process (http://www.americanheart.org)

(12) Allow family members to be present if they choose

(13) Provide for patient comfort (e.g., mouth care, positioning, suctioning)

ii. Discharge planning: Bereavement support services for the family after the patient’s death

Psychosocial—General References

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Standards for acute and critical care nursing practice. Aliso Viejo, Calif: Author, 2000.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. The synergy model of certified practice. Aliso Viejo, Calif: Author, 2003.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR), ed 4. text rev, Washington, DC: Author, 2000.

Biondi, M, Kotzalidis, GD. Human psychoneuroimmunology today. J Clin Lab Anal. 1990;4:22–38.

Caine, RM. Psychological influences in critical care: perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(2):60–70.

Caine, RM, Ter-Bagdasarian, L. Early identification and management of critical incident stress. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(1):59–65.

Carlson, VR, Mroz, I. Barriers to effective patient care. In Grenvik A, Ayres SM, Holbrook PR, et al, eds.: Textbook of critical care, ed 4, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2000.

Curley, MAQ. Patient-nurse synergy: optimizing patients’ outcome. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7:64–72.

Erikson, E. Childhood and society, ed 2. New York: WW Norton, 1963.

Erikson, E. Identity, youth and crisis. New York: WW Norton, 1968.

Fortinash, KM, Holoday-Worret, PA. Psychiatric nursing care plans, ed 3. St Louis: Mosby, 1999.

Grumet, GW. Pandemonium in the modern hospital. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:433–437.

Hardin SR, Kaplow R, eds. Synergy for clinical excellence: the AACN synergy model for patient care. Boston: Jones and Bartlett, 2005.

Holland, C, Cason, CL, Prater, LR. Patient’s recollections of critical care. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1997;16:132–141.

Jastremski, CA, Harvey, M. Making changes to improve the intensive care unit experience for patients and their families. New Horiz. 1998;6(1):99–109.

Keltner, NL, Schwecke, LH, Bostrom, CE. Psychiatric nursing, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby, 2003.

Maslow, AH. Toward a psychology of being. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand, 1968.

Mullen, JE. The synergy model in practice: the synergy model as a framework for nursing rounds. Crit Care Nurse. 2002;22:66–68.

Pettigrew, J. Intensive nursing care: the ministry of presence. Crit Care Clin North Am. 1990;2:503–508.

Pope, DS. Music, noise, and the human voice in the nurse-patient environment. Image. 1995;27:291–295.

Satir, V. Conjoint family therapy. Palo Alto, Calif: Science & Behavior Books, 1967.

Schrader, KA. Stress and immunity after traumatic injury: the mind-body link. AACN Clin Issues. 1996;3:351–358.

Seligmann, J. Variation on a theme. Newsweek. 1990;114:38.

Selye, H. Stress without distress. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1974.

Solomon, GF. Psychoneuroimmunology: interactions between the central nervous system and immune system. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18:1–9.

Topf, M, Bookman, M, Armand, D. Effects of critical care unit noise on the subjective quality of sleep. J Adv Nurs. 1996;24:545–551.

Urban, N. Patient and family responses to the critical care environment. In Kinney MR, Dunbar SB, Brooks-Brunn J, et al, eds.: AACN clinical reference for critical-care nursing, ed 4, St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

US Bureau of the Census. Uses for questions on the Census 2000 forms. retrieved September 26, 2005, from http://census.gov/dmd/www/content.htm, 2000.

Andrews, M, Boyle, J. Transcultural concepts in nursing, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

Arbour, R. Sedation and pain management in critically ill adults. Crit Care Nurse. 2000;20(5):39–56.

Beers, MH, Berkow, R. The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy, ed 17. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck, 1999.

Carpenito-Moyet, LJ. Nursing diagnosis: application to clinical practice, ed 10. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Chlan, L, Tracy, MF. Music therapy in critical care: indications and guidelines for intervention. Crit Care Nurse. 1999;19(3):35–41.

Cullen, L, Titler, M, Drahozal, R. Protocols for practice: family and pet visitation in the critical care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 1999;19(3):84–87.

Gawlinski A, Hamwi D, eds. Acute care nurse practitioner: clinical curriculum and certification review. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1999.

Gerdner, LA, Buckwalter, KC. Music therapy. In Bulechek GM, McCloskey JC, eds.: Nursing interventions: effective nursing treatments, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1999.

Giuliano, KK, Bloniasz, E, Bell, J. Implementation of a pet visitation program in critical care. Crit Care Nurse. 1999;19(3):43–50.

Henneman, EA, Cardin, S. Family-centered critical care: a practical approach for making it happen. Crit Care Nurse. 2002;22(6):12–19.

Leske, JS. Needs of relatives of critically ill patients: a follow-up. Heart Lung. 1986;15:189–193.

Stuart, GW, Sundeen, S. Principles and practice of psychiatric nursing, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby, 2002.

Tullmann, DF, Dracup, K. Creating a healing environment for elders: complimentary and alternative therapies. AACN Clin Issues. 2000;11:34–50.

Bally, K, Campbell, D, Chesnick, K, et al. Effects of patient-controlled music therapy during coronary angiography on procedural pain and anxiety distress syndrome. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(2):50–51.

Keegan, L. Protocols for practice: applying research at the bedside. Alternatives and complimentary modalities for managing stress and anxiety. Crit Care Nurse. 2000;20:93–96.

Simon, NM, Pollack, MH, Labbate, LA, et al. Recognition and treatment of anxiety in the intensive care unit patient. In Irwin RS, Rippe JM, eds.: Intensive care medicine, ed 5, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2003.

Wong, HLC, Lopez-Nahas, V, Molassiotis, A. Effect of music therapy on anxiety in ventilator dependent patients. Heart Lung. 2001;30:376–387.

Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: Acute pain management in adults: operative procedures, Quick reference guide for clinicians No 1, AHCPR Pub No 92–0019, Rockville, Md, February 1992, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services.

American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine Consensus document: Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain Glenview, Ill: American Academy of Pain Medicine; 2001 Available at http://www.asam.org/ppol/paindef.htm

American Geriatrics Society. The management of pain in older persons: AGS panel on chronic pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(5):635–651.

American Pain Society. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain, ed 5. Glenview, Ill: Author, 2003.

American Society of Pain Management Nurses. ASPMN position statement: pain management in patients with addictive disease. Pensacola, Fla: Author, 2002.

Ardery, G, Herr, K, Titler, M, et al. Assessing and managing acute pain in older adults: a research base to guide practice. Medsurg Nurs. 2003;12(1):7–18.

Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: Acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma, Clinical practice guideline No 1, AHCPR Pub No 92–0032, Rockville, Md, 1992, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Cullen, L, Greiner, J, Titler, MG. Pain management in the culture of critical care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13(2):151–166.

Dalton, JA, Coyne, P. Cognitive-behavioral therapy: tailored to the individual. Nurs Clin North Am. 2003;38(3):465–476.

Graf, C, Puntillo, K. Pain in the older adult in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2003;19(4):749–770.

Hamill-Ruth, RJ, Marohn, ML. Evaluation of pain in the critically ill patient. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15(1):35–54.

Jacobi, J, Fraser, GL, Coursin, BD, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):119–141.

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Comprehensive accreditation manual for hospitals (CAMH): the official handbook. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill: Author, 2004.

Kanner R, ed. Pain management secrets, ed 2, Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2003.

Koestler, AJ, Doleys, DM. The psychology of pain. In: Tollison CD, Satterthwaite JR, Tollison JW, eds. Practical pain management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

Lang, JD, Jr. Pain: a prelude. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15(1):1–16.

Loeser JC, Butler SH, Chapman CR, et al, eds. Bonica’s management of pain, ed 3, Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

McCaffery, M. Nursing practice theories related to cognition, bodily pain, and man-environment interactions. Los Angeles: University of California at Los Angeles Student’s Store, 1968.

McCaffery, M, Pasero, C. Pain: clinical manual, ed 2. St Louis: Mosby, 1999.

Mersky, H. Classification of chronic pain: description of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Pain. 1979;3(suppl):S217.

Munden J, Eggenberger T, Goldberg KE, et al, eds. Pain management made incredibly easy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

National Pharmaceutical Council, Inc. Pain: current understanding of assessment, management, and treatments. Reston, Va: Author, 2001.

Pace, S, Burke, T. Intravenous morphine for early pain relief in patients with acute abdominal pain. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(12):1086–1092.

Pasero, C. Pain in the critically ill patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2003;18(6):422–425.

Puntillo, K. Pain: assessment, treatment and the coming thunder, interview by Michael Villaire. Crit Care Nurse. 1995;15(6):75–81.

Puntillo, KA, Morris, AB, Thompson, CL, et al. Pain behaviors observed during six common procedures: results from Thunder Project II. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(2):421–427.

Puntillo, KA, White, C, Morris, AB, et al. Patients’ perceptions and responses to procedural pain: results from Thunder Project II. Am J Crit Care. 2001;10(4):238–251.

Rakel, B, Barr, JO. Physical modalities in chronic pain management. Nurs Clin North Am. 2003;38(3):477–494.

Snyder, M, Wieland, J. Complementary and alternative therapies: what is their place in the management of chronic pain? Nurs Clin North Am. 2003;38(3):495–508.

St. Marie B, ed. ASPMN: core curriculum for pain management nursing. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

Titler, MG, Rakel, BA. Nonpharmacologic treatment of pain. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2001;13(2):221–232.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality http://www.ahrq.gov

American Academy of Pain Management http://www.aapainmanage.org

American Academy of Pain Medicine http://www.painmed.org

American Pain Society http://www.ampainsoc.org

American Society for Pain Management Nursing http://www.aspmn.org

American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses http://www.aspan.org

American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine http://www.asra.com

International Association for the Study of Pain http://www.iasp-pain.org

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations http://www.jcaho.org

Medscape. http://www.medscape.com.

Oncology Nursing Society http://www.ons.org

Pain/Palliative Care Resource Center http://www.cityofhope.org/prc/

Delirium (Acute Confusional State)

Burns, SM. Delirium during emergence from anesthesia: a case study. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(1):66–69.

Inouye, SK, Van Dyke, CH, Alessi, CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:941–948.

Truman, B, Ely, EW. Monitoring delirium in critically ill patients: using the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2003;23(2):25–36.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington DC: Author, 2000.

Schumacher, L. Identifying patients “at risk” for alcoholic withdrawal syndrome and a treatment protocol. J Neurosci Nurs. 2000;32:158–163.

Sellers, EM, Sullivan, JT, Somer, G. Characterization of DSM-III-R criteria for uncomplicated alcohol withdrawal provides an empirical basis for DSM-IV. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:442–447.

Sommers, MS, Dyehouse, JM, Howe, SR, et al. Nurse, I only had a couple of beers: validity of self-reported drinking before serious vehicular injury. Am J Crit Care. 2002;11:106–114.

Sullivan, JT, Sykora, K, Schneiderman, J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84:1353–1357.

Cummins, RO. Advanced Cardiac Life Support provider manual. Dallas, Tex: American Heart Association, 2001.

Simons, M. Patient contracting. In Bulechek GM, McCloskey JC, eds.: Nursing interventions: effective nursing treatments, ed 3, Philadelphia: Saunders, 1999.

Chapple, HS. Changing the game in the intensive care unit: letting nature take its course. Crit Care Nurse. 1999;19(3):25–34.

Cummins, RO. Advanced Cardiac Life Support provider manual. Dallas, Tex: American Heart Association, 2001.

Kübler-Ross, E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

Myers, TA, Eichhorn, DJ, Guzzetta, CE, et al. Family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitation: the experience of family members, nurses, and physicians. Am J Nurs. 2000;100:32–42.