Psychosocial aspects of adaptation and adjustment during various phases of neurological disability

ROCHELLE McLAUGHLIN, MS, OTR/L, MBSR and GORDON U. BURTON, PhD, OTR/L

After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to:

1. Describe adaptation and adjustment as parts of a flexible and flowing process, not as static stages.

2. Describe elements of the grief process that deal with age, cognition, and developmental level.

3. Integrate the elements of mindfulness, problem solving, loss, cognitive functioning, and coping, as well as significant others’ coping and learning styles, into the treatment process to encourage adaptation.

4. Integrate the family of the client and the client’s styles of coping into therapeutic treatment strategies to be used in the clinic.

5. Respect aspects of sexuality in treatment and consider them when treating the client.

6. Accept the role of patient advocate and the responsibility to report any abuse. Each clinician is responsible for knowing state law as part of her or his state licensure requirements.

Psychological adjustment

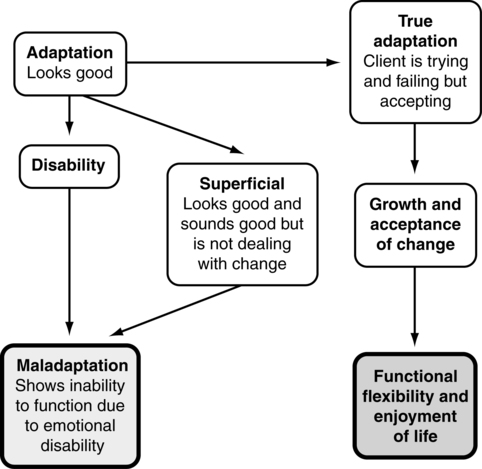

In clinical practice, theoretical foundations for adjustment to disability appear to be elusive because they represent a fluid process: all people are constantly changing. This is especially true for people who have recently become physically disabled. They do not reach a certain state of adjustment and stay there but progress through a series of adaptations. Therapists see clients in a crisis state1–6 and therefore identify their adjustment patterns from this frame of reference. How well the individual adjusts to the crisis, however, does not necessarily indicate how well he or she will adjust to all aspects of the disability, or the rate of progress from one point of adaptation to another.6–15 Disabilities are an unimaginable insult to an individual’s self-perception.16–19 A month or even a year after the injury may not be long enough to put the disability into perspective.10,16,17,19–22

For most people, progressing from the shock of injury to the acceptance of and later adaptation to disability is a process filled with psychological ups and downs. Several authors have discussed the possible stages of adjustment and grieving.10,14 The research of Kübler-Ross23 into death and dying has application to this topic of adjustment to disability. She discussed the concept of loss and grief in relation to life; loss of function may result in just as profound a reaction. The practice of mindfulness may be important in disengaging individuals from automatic thoughts, habits, and unhealthy behavior patterns and thus could play a key role in fostering informed and self-endorsed behavioral regulation, and adjustment to catastrophic life events.24 Peretz25 and others26–28 discuss the grieving process in relation to the loss of role function as well as loss of body function. These losses must be grieved for before the client can fully benefit from therapy or adjust to a changed body and lifestyle. Therapists must be aware that the client can and must deal with the death of certain functional abilities.

Some authors have questioned the concept of stages of adjustment,1,29 and call for more empirical research into adaptation and adjustment; this has been started.30 One alternative concept that has been developed is cognitive adaptation theory.31 This concept examines self-esteem, optimism, and control. In this theory, if the individual feels good about himself or herself and has an optimistic view of life and a sense of control over life, the individual will adapt to the functional limitations and will participate in life. Cognitive adaptation theory does not consider the organic changes that may take place when brain damage has occurred, but the basic goals are very much worth taking into consideration. These should be examined in relation to the limbic system (see Chapter 5) because limbic involvement is crucial to reaching all goals and plays a key role in establishment of motivation.

We understand more about suffering than we think

Clinical professionals have a wellspring of knowledge to draw from beyond their extensive traditional education. We are all human beings, and being human comes with a great deal of innate suffering. If we bring awareness to the fact that we have all suffered in our lives, we may not feel so separate from our clients. We may realize that we have more to offer our clients than just the knowledge we have gained about their disability and how we might help them gain function. The more we allow ourselves to slow down and be present with suffering—our own or that of another—the more we will be able to be open to the mystery and joy of our lives just as they are without requiring them to be any different.32 It may be our lifetime’s journey to be servants of the healing arts; this is our job, and it also takes enormous skill and bravery to bear witness to the full catastrophe of the human condition.32 One of the benefits of our profession is the stimulus to examine our lives through the experiences of others. This can improve our function and help us grow as professionals and individuals, but if we are not open to the clients’ experiences we may not find a reason to examine and grow from our own experiences.

Awareness of psychological adjustment in the clinic, society, and culture

Working with individuals with functional limitations requires that we cultivate a holistic and all-encompassing perspective: to visualize how they might best participate within their own homes and communities, and in the context of their society and a given time. This is a dynamic and constantly changing process. The clinician must develop an intervention that will appropriately stimulate the individual and all their potential caregivers to maximize the potential for the highest-quality life possible. The skilled clinician initially evaluates the individual’s physical and cognitive capabilities depending on the type of functional limitations. The more subtle psychological aspects of the client’s ability to function need to be assessed at some level. These include the individual’s support system and/or family network and its ability to adjust to the imminent changes in lifestyle. It would be a tragic situation for a clinician to ignore the individual’s psychological adjustment or consider it to be less important in any way.19,33–36

Livneh and Antonak37 have introduced a consolidated way to look at adaptation as a primer for counselors, which should be examined by therapists. They use some of the same basic concepts, such as stress, crisis, loss and grief, body image, self-concept, stigma, uncertainty or unpredictability, and quality of life, to frame their approach. They also consider the concepts of shock, anxiety, denial, depression, anger and hostility, and adjustment in a format that is usable by the therapist.

Livneh and Antonak37 mention that one of the aspects that the therapist must watch out for is a form of coping called disengagement. This style of coping may be demonstrated through denial or avoidance behavior that can take many forms. It can result in substance abuse, blame, or just refusal to interact. Research regarding people with head injuries has demonstrated that if a premorbid coping style for a person was to use alcohol or other drugs, the client may revert to these same styles of coping, which can result in poor physical and emotional rehabilitation.38 It is important to help the individual out of this quagmire. The skills of a therapist are likely not enough to do this in the short time that the client is in treatment, so a referral to social work, psychology, or psychiatry is required to help support the long-term process. It is still the therapist’s job to understand the process of adjustment, the indications regarding how an individual is adjusting, key concepts for how to engage with an individual who is adjusting, and how to set personal boundaries so that the clinician is less likely to be overwhelmed by the process of adjustment and disability. In light of all this, it is still the primary job of the therapist to help promote and maximize the engagement in functional activities. These activities are behaviors that must be goal oriented (patient, family, and therapist driven), demonstrating problem solving and information seeking and involving completion of steps to positively move forward into life with the disability and to maximize independence (promoting function).

Growth and adaptation

The clinician must keep in mind the context from which the client is coming. Just days or even hours ago the individual may have been going about daily life without difficulty. The trauma may be multifaceted: (1) physical trauma, (2) emotional trauma occurring to the individual’s support system, and (3) trauma of each of these systems interacting (the support system trying to protect the individual, and the client trying to protect the support system). The interaction of these multifaceted components of the trauma may lead to posttraumatic distress syndrome. This syndrome usually happens within the first 6 months after the injury. This syndrome may be observed more often in women39 but because of cultural barriers it can be hidden in men. It happens more often when there has been a near-death situation.40,41 The client may blame others, try to protect others, or be so self-absorbed that little else in the world may be seen or heard. It may be helpful to get psychological help for the individual early in therapy if this is preventing optimal outcomes or creating obstacles in therapy.4,15,42–45

It is the therapist’s job to develop a trusting relationship with the client. Through this relationship the individual can be guided to focus on the goals of therapy and work on a positive perspective about the future. One of the errors of the medical system is that of focusing on the disease outcomes and pathology and not on the person and the positive capabilities still within the individual’s grasp.19 This focus on the negative or loss may cause the individual to see only the injury, disease, or pathological condition and nothing else. In a Veterans Administration hospital, spouses of people with spinal cord injuries formed a group in which the group’s focus was on why the partners got married in the first place; the group never looked at the physical limitations as disabling. After a little while people came to the conclusion that they did not marry their spouses for their legs and the fact that the legs no longer worked was not a major issue after all. This started the decentering from the medical disability model and the focus started to be placed on the people and the families’ future. If we can help clients focus on their functions and not their dysfunctions, the effect of therapy after treatment will be much better. More work needs to be done to help clients see the potential they will have in the future to live their lives with the highest quality possible.34,46–50 The World Health Organization developed a model that differentiates the disease pathology model of medicine and focuses on individuals’ activities in life and the ability to participate in those interactions. This model, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), has been enthusiastically accepted by the therapy world, and the professions of both occupational and physical therapy use it as a reference model for practice.

Focusing on how to participate, move, and function in the world is one of the keys to helping the client and the family work toward its future.33,49,51–54

The therapist needs to help the client focus on the direction of treatment objectives and to demonstrate how therapy translates into meeting the client’s goals.19,55 To discover the client’s true goals, the therapist must gain the trust of the client and establish sound lines of communication. Distrust from health professionals may obstruct the adjustment process and lead to negative consequences.56 Whenever possible, the client’s support system should be enlisted to help establish realistic support for the client and the goals of both the client and the family. It has been found that if the client trusts the health professional, the client will be more adherent and will seek assistance when it is needed (see Chapter 5 for additional information).57,58

A new normal

When we experience a decline in our ability to carry out our everyday routine tasks, regardless of the cause of our “disability,” we may experience incredible degrees of despair. Many societies emphasize a very specific idea of what it means to be normal. There doesn’t appear to be a great deal of flexibility in what this standard of normal is, regardless of one’s cultural background. When an individual fails to live up to or no longer fits this norm, there can exist a tremendous amount of mental and emotional suffering. Because our bodies and minds are so intricately connected, our physical being is adversely affected by the mental and emotional anguish. On top of what the individual may already be experiencing physically, suddenly there is another layer of mental-physical anguish that is far too easily ignored and unattended to by clinical professionals. However, once we are aware of the multifaceted potential for human suffering with regard to adjusting to a disability, we may be empowered to assist the individual with a nonlinear, multifaceted approach. Researchers and theorists from various psychotherapy traditions have begun to explore the potential value of the therapeutic relationship by making direct references to different levels of validation as a means of demonstrating warmth, genuineness, empathy, and acceptance and reiterate how important it is for therapists to reflect back to the patient that their feelings, thoughts, and actions make sense in the context of their current experience. The therapist articulates an expectation that the treatment collaboration will be effective in an attempt to convey hope and confidence in their ability to work together.59

We can guide our clients in identifying a new normal for themselves, all the while allowing them and their support system to grieve the loss of the old normal. As the Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer described in her book Mindfulness, “if we are offered a new use for a door or a new view of old age [or disability], we can erase the old mindsets without difficulty.”60 We can offer our clients a new view of themselves by showing them what they are capable of as they rebuild their lives. We can also help them acknowledge what is present in this moment and what the reality of the situation is. This does not have to be a problem to be suffered over but is a situation to be dealt with carefully and fully in the present moment. A woman who has lived with multiple sclerosis for over 30 years described how the relief of suffering does not require restoring physical function to some perceived level of normality. “Suffering is relieved to the extent that patients can learn to integrate bodily disorder and physical incapacity into their lives, to accommodate to a different way of being” (p. 591).61 According to research by De Souza and Frank,61 their subjects with chronic back pain expressed regret at the loss of capabilities and distress at the functional consequences of those losses. They found that facilitating “adjustment” to “loss” was more helpful than implying the potential for a life free of pain as a result of therapeutic interventions.

Without any need to apologize for their loss, just simply being with them in the moment in a nonjudgmental way and allowing them to grieve can be a powerful tool for healing. Acknowledging the loss and the suffering may help clients move forward with their lives in a new way. “Acceptance [of what is] doesn’t, by any stretch of the imagination, mean passive resignation. Quite the opposite. It takes a huge amount of fortitude and motivation to accept what is—especially when we don’t like it—and then work wisely and effectively as best we possibly can with the circumstances we find ourselves in and with the resources at our disposal, both inner and outer, to mitigate, heal, redirect, and change what can be changed.”62

Practice: mindful planning and visualization of future

Find a time when you are alone; you need only a few minutes every day for this practice.

Find a time when you are alone; you need only a few minutes every day for this practice.

Allow this time to be specifically for future planning and visualization, not worrying.

Allow this time to be specifically for future planning and visualization, not worrying.

If you find yourself worrying about the future at other times during the day, acknowledge that there will be a specific time devoted to planning and visualizing. Worrying throughout the day will bring a great deal of mental anguish during times when you need to focus attention on an important task or rehabilitation intervention.

If you find yourself worrying about the future at other times during the day, acknowledge that there will be a specific time devoted to planning and visualizing. Worrying throughout the day will bring a great deal of mental anguish during times when you need to focus attention on an important task or rehabilitation intervention.

Use a journal to record thoughts and ideas on paper so that the thoughts do not have to stay in the mind and be rehearsed. Write down concerns as well as plans.

Use a journal to record thoughts and ideas on paper so that the thoughts do not have to stay in the mind and be rehearsed. Write down concerns as well as plans.

Try to let go of planning during daily activities and tasks until the next scheduled Mindful Planning Session, or, if necessary, allow this moment to be the next planning session but be sure to stop whatever else you are doing and be fully present in the planning process.

Try to let go of planning during daily activities and tasks until the next scheduled Mindful Planning Session, or, if necessary, allow this moment to be the next planning session but be sure to stop whatever else you are doing and be fully present in the planning process.

Societal and cultural influences

Culture, subcultures, and the culture and beliefs of the given family are all aspects of the client that the therapist must be aware of.22,52,63–69 This concept gets into the beliefs about the world and maybe a belief about the cause of the disability or at least how the client is viewing the disability. Asking “why do you think this happened to you?” can lead to an enlightening experience. “Causes” may range from “God is punishing me” to “I deserved it” to “life is against me.”

From an early age, people in our society are exposed to misconceptions regarding the disabled person.70–73 If in the therapeutic environment, however, the client and family have their misconceptions challenged constantly, they may start reformulating their concept of the role of the disabled person. As this process progresses, therapists and other staff can help make the expectations of the disabled person more realistic. Therapists can schedule their clients at times when they will be exposed to people making realistic adjustments to disabilities. Use of individuals who have been successfully rehabilitated as staff members (role models) can help to dispel the misconception that people with disabilities are not employable.74–76

This process of adaptation to a new disability can be considered as a cultural change from a majority status (able bodied) to a minority status (disabled). Part of the adaptation process can be considered as an acculturation process, and the therapist can help facilitate this process.16,72,77,78

The cultural background of the individual also contributes to the perception of disability and to the acceptance of the disabled person. Trombly79 states that perception and expression of pain, physical attractiveness, valuing of body parts, and acceptability of types of disabilities can be culturally influenced. One’s ethnic background can also affect intensity of feelings toward specific handicaps, trust of staff,79 and acceptance of therapeutic modalities.80–84

Gaining trust is one of the crucial links in any meaningful therapeutic situation.58,85,86 Trust will create an environment that facilitates communication, productive learning, and exchange of information.75,86 Trust is important in all cultures and will be fostered by the therapist who is sensitive to the needs of the client. This sensitivity is necessary with every client but will be manifested in many different ways, depending on the background and needs of the individual in therapy. A client of one culture may feel that looking another person in the eyes is offensive, whereas in another culture refusal to look into someone’s eyes is a sign of weakness or lack of honesty (shifty eyed).87 Thus although it is impossible to know every culture or subculture with which the therapist may come into contact, the therapist must attempt to be sensitive to the background of the client. Even if the therapist knows the cultural norms, not every person follows the cultural patterns, and thus every client needs to be treated as an individual in the therapeutic relationship. It should be the therapist’s job to be sensitive to the subtle nonverbal and verbal cues that indicate the level of trust in the relationship. The therapist will obtain this information by being open to the client, not open to a textbook. The client is the owner of this information and will share it with everyone he or she trusts.

Trust is often established in the therapeutic relationship through physical activities. The act of asking a client to transfer from the chair to the bed can either build trust or destroy the potential relationship. If the client trusts the therapist just enough to follow instructions to transfer but then falls in the process, it may take quite some time to reestablish the same level of trust, assuming that it can ever be reestablished. This trusting relationship is so complex and involves such a variety of levels that the therapist should be as aware of attending to the client’s security in the relationship as to the physical safety of the client in the clinic.58,85 If the client believes that the therapist is not trustworthy in the relationship, then it may follow that the therapist is not to be trusted when it comes to physical manipulation of a disabled body. If the client does not know how to use the damaged physical body and thus cannot trust the body, then lacking trust in the therapist will only compound the stress of the situation.58,85,88 Chapter 8 provides more information on the neurological components of this interaction during the intervention process.

The client’s culture may be alien to the therapist, even though both the clinician and client may be from the same geographical region. A client’s problems of poverty, unemployment, and a lack of educational opportunities76,86,89,90 can all result in the therapist and client feeling that therapy will be unsuccessful, even before the first session has begun. Such preconceived concepts held by both parties may not be warranted and must be examined. These preconceived concepts can be more reflective of failure of rehabilitation than any physical limitation of the client.

Cultural and religious values may also result in the client feeling that he or she must pay for past sins by being disabled and that the disability will be overcome after atonement for these sins. Such a client may not be inclined to participate in or enjoy therapy. The successful therapist does not assault the client’s basic cultural or religious values but may recognize them in the therapy sessions. If the therapist feels that the culturally defined problems are impeding the therapeutic process, the therapist may offer the client opportunities to reexamine these cultural “truths” in a nonjudgmental way and may help the client redefine the way the physical limitations and therapy are seen.91 Religious counseling could be recommended by the therapist, and follow-up support in the clinic may be given to the client to view therapy not as undoing what “God has done” but as a way of proving religious strength. Reworking a person’s cultural and religious (cognitive) structure is a sensitive area, and it should be handled with care and respect and with the use of other professionals (social workers and religious and psychological counselors) as appropriate.

The hospital staff can be encouraged to establish groups in which commonly held values of clients can be examined and possibly challenged.16,91–97 Such groups can lead the client to a better understanding of priorities and may help the person see the relevance of therapy and the need to continue the adjustment process. This can also prepare the client to better accept the need for support groups after discharge. The therapist may be able to use information from such group sessions to adjust the way therapy sessions are presented and structured to make therapy more relevant to the client’s values and needs. Value groups or exercises98 can be another means used by the therapist for evaluation and understanding of the client.

Beliefs and values of cultures and families can play a profound role in the course of treatment. Such things as physical difficulties, which can be seen, are usually better accepted than problems that cannot be seen, such as brain damage that changed an individual’s cognitive abilities or personality.99 A person with a back injury may be seen as lazy, whereas a person with a double amputation will be perceived as needing help. At the same time, in some cultures a person who has lost a body part may be seen as “not all there” and should be avoided socially. Therefore being attuned to the culture and beliefs of the client is imperative in therapy. The reader is encouraged to refer to texts on cultural issues in health care such as Culture in Clinical Care by Bonder, Martin, and Miracle100; Cultural Competence in Health Care: A Practical Guide by Rundle, Carvalho, and Robinson101; and Caring for Patients from Different Cultures by Galanti102 for more detailed discussions on how culture and beliefs affect health care.

Establishment of self-worth and accurate body image

Self-worth is composed of many aspects, such as body image, sexuality, and the ability to help others and to affect the environment. The body image of a client is a composite of past and present experiences and of the individual’s perception of those experiences. Because body image is based on experience, it is a constantly changing concept. An adult’s body image is substantially different from the body image of a child and will no doubt change again as the aging process continues. A newly disabled person is suddenly exposed to a radically new body, and it is that individual’s job to assess the body’s capabilities and develop a new body image. Because the therapist is at least partially responsible for creating the environmental experiences from which the client learns about this new body, the therapist must be aware of the concept. In the case of an acute injury, the client has a new body from which to learn. The therapist can promote positive feelings as the therapist instructs the client how to use this new body and to accept its changes.1,16,20,27,103,104

The loss of use of body parts can cause a person to perceive the body as an “enemy” that needs to be forced to work or to compensate for its disability. In all cases the body is the reason for the disability and the cause of all problems. The need for appliances and adaptive equipment can create a sense of alienation and lack of perceived “lovability” resulting from the “hardness of the hardware.” People tend to avoid hugging someone who is in a wheelchair or who has braces around the body because of the physical barrier and because of the person’s perceived fragility; a person with physical limitations is certainly not perceived as soft and cuddly.20,27,52,102,103 Both the perception that these individuals are not lovable and their labored movements can sap the energy of the disabled and discourage social interaction or life participation. To accept the appliances and the dysfunctional body in a way that also allows the disabled person to feel loved is surely a major challenge.

In the case of a person who will be disabled for the long term, such as the person with cerebral palsy or Parkinson disease, the therapist is attempting to teach the client how to change the previously accepted body image to one that would allow and encourage more normal function. In short, the therapist has two roles. One role is to help lessen the disabled body image. The second is to teach a functional disabled body image to a newly disabled person. The techniques may be the same, but in both cases the client will have to undergo a great amount of change. The person with a neurological disorder or neurologically based disability may assume that he or she will not be capable of accomplishing many things with his or her life. The therapist is in a unique position to encourage development of and maximize the client’s level of functional ability. The individual may then expect more of himself or herself. The newly disabled person must change the expectations; however, he or she has little concept of what is realistic to expect of this new body. At this point, role models can be used to help shape the client’s expectations. If the client is unable to adjust to the new body and change the body image and self-expectations, life may be impoverished for that individual. Pedretti105 states that the client with low self-esteem often devalues his or her whole life in all respects, not just in the area of physical dysfunction.1,16,20,27,103,104

One way the client can start exploring this new body is by exploring its sensations and performance. Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn developed a guided “body scan” meditation that can help individuals learn how to become more connected and in tune with the sensations of the body.62 This kind of practice is about learning to pay attention to the body in a new way and can be very helpful in developing an accurate body image and improve self-awareness. The client with a spinal cord injury may also use the sensation of touch to “map out” the body to see how it reacts.106 They may ask themselves the following questions: Is there a way to get the legs to move using reflexes? Can positioning the legs in a certain way aid in rolling the wheelchair or make spasms decrease? What, if anything, stimulates an erection or lubrication? Such exploration will start the client on the road to an informed evaluation of his or her abilities.

The therapist’s role is to maximize the client’s perceptions of realistic body functioning. Exercises can be developed that encourage exploration of the body by the individual and, if appropriate, the significant partner. Functioning and building an appropriate body image will be more difficult if intimate knowledge of the new body is not as complete as before injury.9 The successes the client experiences in the clinical setting coupled with the client’s familiarity with his or her new body will result in a more accurate body image and will contribute to the client’s feelings of self-worth.

The last aspect of self-worth is often overlooked in the health fields. This aspect is the need that people have to help others.107 People often discover that they are valuable through the act of giving. Seeing others enjoy and benefit from the individual’s presence or offering increases self-worth. Situations in which others can appreciate the client’s worth may be needed. Unless the client can contribute to others, the client is in a relatively dependent role, with everyone else giving to him or her without the opportunity of giving back. Achieving independence and then reaching out to others, with therapeutic assistance if necessary, facilitates the individual’s more rapid reintegration into society. The therapist should take every opportunity to allow the client to express self-worth to others through helping.

The ability to expand one’s definition of oneself is a key factor in adjusting to a disability. Expanding the definition of oneself in terms of all the roles and responsibilities one has can help the individual comprehend the enormity of who he or she is. The individual may begin to understand how he or she is so much greater than just the job he or she once performed and so much greater than the role he or she once played. This practice can cultivate understanding of how complex our species is and how much we have to offer the world, differently abled or not (see journal activity, Box 6-1).

Sense of control

As Drs. Roizen, and Oz stated in their book You: The Owner’s Manual, we can control our health destiny.108 Although we can’t always control what happens to us (no matter how fit we are), there are some things we can control: our attitude, our determination, and our willingness to take our own health into our own hands.108

Dr. Jill Bolte-Taylor says this eloquently in a passage from her book:

“I’ve often wondered, if it’s a choice, then why would anyone choose anything other than happiness? I can only speculate, but my guess is that many of us don’t exercise our ability to choose. Before my stroke, I thought I was a product of my brain and had no idea that I had some say about how I responded to the emotions surging through me. On an intellectual level, I realized that I could monitor and shift my cognitive thoughts, but it never dawned on me that I had some say in how I perceived my emotions. . . . What an enormous difference this awareness has made in how I live my life.”109

As Dr. Bolte-Taylor describes, all of us have the choice to be in relation to the present moment fully, or we can allow our thoughts and emotions to “take us for a ride” as though we were on automatic pilot.109 If we allow our minds and emotions to take over our experience of the present moment, we can easily be dragged along into rehashing our past events that led up to the disability, which can create more suffering and emotional anguish. We also may be rehearsing what our lives will be like without allowing the dust to settle, without waiting until we have a clearer picture of what implications the disability may have for us. An unacknowledged rehashing and rehearsing can create an incredible sense of lack of control over one’s life, thereby increasing anxiety and depression. Approximately 70% of our thoughts in any particular waking state can be considered to be daydreams, and they can often be unconstructive.110 In an experience sampling method, Klinger and his colleagues found that “active, focused problem-solving thought”111 made up only 6% of the waking state. According to Baruss, “it would make more sense to say that our subjective life consists of irrational thinking with occasional patches of reason”110 while we are participating in our daily activities. Especially when one is participating in menial, basic self-care activities, our mind is often in another place. If an individual is frequently disconnected from the present moment, tending to ruminate over the past or future events, he or she may experience significant negative effects from this distraction. Rumination, absorption in the past, rehashing, or fantasies and anxieties about the future can pull one away from what is taking place in the present moment. Awareness or attention can be divided, such as when people occupy themselves with multiple tasks at one time or preoccupy themselves with concerns that detract from the quality of engagement with what is focally present, and this can increase anxiety and depression.112

According to Drs. Oz and Roizen,108 these emotions can cause high blood pressure, as well as disrupting the body’s normal repair mechanism, and also constrict our blood vessels, making it even harder for enough blood to work its way through the body. They go on to say that learning relaxation techniques such as yoga and meditation can help us handle these damaging feelings in a healthier way. We know now that these mind states affect our bodies profoundly—for example, a feeling of helplessness appears to weaken the immune system.108 If we can teach our clients to be mindful of and pay attention to their “mind states”—also known as “thoughts”—at any given moment during therapeutic intervention, we may be able to encourage a greater sense of control and facilitate greater mental and emotional adjustment to the individual’s disability. According to a 2008 article by Ludwig and Kabat-Zinn in JAMA, “the goal of mindfulness is to maintain awareness moment by moment, disengaging oneself from strong attachment to beliefs, thoughts, or emotions, thereby developing a greater sense of emotional balance and well-being.”113 Anat Baniel, in her book Move into Life, describes how research shows that the moment we bring attention and awareness to our movements moment by moment, the brain resumes growing new connections and creating new pathways and possibilities for us.114

According to a research study by Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn115 of the Stress Reduction Program at the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society, the practice of mindfulness meditation used by chronic pain patients over a 10-week period showed a 65% reduction on a pain rating index. Large and significant reductions in mood disturbance and psychiatric symptoms accompanied these changes and were stable on follow-up. Another study looked at brain imaging and immune function after an 8-week training program in mindfulness meditation.116 The study demonstrated that this short program in mindfulness meditation produced demonstrable effects on brain and immune function. The results of a clinical intervention study by Brown and Ryan112 showed that higher levels of mindfulness were related to lower levels of both mood disturbance and stress before and after the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) intervention. Increases in mindfulness over the course of the intervention predicted decreases in these two indicators of psychological disturbance. Evidence has indicated that those faced with a life-threatening illness often reconsider the ways in which they have been living their lives, and many choose to refocus their priorities on existential issues such as personal growth and mindful living.117

These findings suggest that meditation may change brain function and immune function in positive ways. “Meditation” as it is taught in this 8-week program is simply an awareness and attention training: a way of learning how to pay attention in the present moment to our thoughts and emotions and coming to understand how our thoughts and emotions affect our bodies. It may sound simple but actually can be incredibly challenging. However, an instant stress reliever can be bringing awareness to the breath. Deep breathing can act as a mini-meditation and from a longevity standpoint is an important stress reliever.108 Shifting to slower breathing in times of tension can help calm us and allow us to perform, whether mentally or physically, at higher levels.108

Another study, focused on Coping Effectiveness Training (CET), consisted of weekly 60-minute psychoeducational group intervention sessions focused into six topic areas and was adapted from the protocol Coping Effectively with Spinal Cord Injury.118 The treatment protocol was structured to provide education and skill building in areas of awareness of reactions to stress; situation appraisal; coping strategy choice; interaction among thoughts, emotions, and behaviors; relaxation; problem solving; communication; and social support.119 There was a significantly positive correlation between the learned coping strategies and the disabled individual’s ability to adjust in a healthy way.

Hope and spiritual aspects to adjustment

Through great suffering there is incredible potential for us to transcend the mental and emotional limits of the physical body. As clinical professionals we need to be aware of this capability. As described by Dr. E. Cassel in the New England Journal of Medicine, “Transcendence is probably the most powerful way in which one is restored to wholeness after an injury of personhood. When experienced, transcendence locates a person in a far larger landscape. The sufferer is not isolated by pain but is brought closer to a transpersonal source of meaning and to the human community that shares those meanings. Such an experience need not involve religion in any formal sense; however, in its transpersonal dimension, it is deeply spiritual.”120 Parker Palmer, a writer and teacher, describes it this way: “Treacherous terrain, bad weather, taking a fall, getting lost—challenges of that sort, largely beyond our control, can strip the ego of the illusion that it is in charge and make space for true self to emerge.”121 Eckhart Tolle describes the ego as complete identification with form—physical form, thought form, emotional form.122 The more we are identified with the physical realm, the more we will suffer when our attachment to stuff or “form” becomes torn.

“For all of us, our willingness to explore our fears, to live inside helplessness, confusion, and uncertainty, is a powerful ally. Acknowledging our repeated exposure to human suffering—our own and others’—and the seductive draw of numbness and melancholy that provides temporary escape is necessary if we are to be renewed.”32 Dr. Santorelli goes on to say that “there is no way out of one’s inner life, so one had better get into it.”32 “On the inward and downward spiritual journey, the only way out is in and through.”121

Practice: the willingness to embrace what is

1. Become aware of the moments when “resistance to what is” is noticed. This may manifest itself as anxiety, sadness, fear, depression, anger.

2. As soon as anger arises (for example), notice how it manifests itself physically in the body. It may be tension in the muscles, a quickened or palpitating heartbeat, or sweating.

3. Note what the sensation feels like in the body without trying to make the moment different than it is. Acknowledge whatever is present in the moment.

4. Note that we are not the anger, we are the awareness of it.

5. Note what the awareness does. Journal any thoughts or feelings about the practice.

Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn, in his book Coming to Our Senses, states, “It seems as if awareness itself, holding the sensations without judging them or reacting to them, is healing our view of the body and allowing it to come to terms, at least to some degree, with conditions as they are in the present moment in ways that no longer overwhelmingly erode our quality of life, even in the face of pain or disease.”62

“Mystery surrounds every deep experience of the human heart: the deeper we go into the heart’s darkness or its light, the closer we get to the ultimate mystery of God [the Universe].”121

Religious and spiritual beliefs can be assistive in the process of adjusting to a disability. Johnstone, Glass, and Oliver highlight that religion and spirituality are important coping strategies for persons with disabilities.67 According to Dr. Jill Bolte-Taylor in her book My Stroke of Insight: A Brain Scientist’s Personal Journey, “Enlightenment is not a process of learning but a process of unlearning.”109 Western society rewards the skills of the “doing” left brain much more than the “being” right brain, which can significantly hinder our process of spiritual growth. The focus of our lives becomes more about obtaining positions, roles, and “stuff.” We begin to identify ourselves with all of this when in reality the positions, roles, and stuff can be taken from us at any moment. “When we are obsessed with . . . productivity, with efficiency of time and motion, with projecting reasonable goals and making a beeline toward them, it seems unlikely that our work will ever bear fruit, unlikely that we will ever know the fullness of spring in our lives.”121

There is a much deeper definition of ourselves that goes beyond all of the material possessions and the roles that we may ever play. According to Eckhart Tolle,122 when forms that we identify with, that give us a sense of self—such as our physical bodies—collapse or are taken away, it can lead to a collapse of the ego, because ego is identification with “form.” When there is nothing to identify with anymore, who are we? When forms around us die, or death approaches, Spirit is released from its imprisonment in matter. We can finally understand that our essential identity is formless, spiritual.122 Cultivating greater understanding of these concepts and delving more into the spirit can provide a great deal of relief for all of us who are suffering.

It is the belief in life as part of the eternal stream of time, that each of us came from somewhere and is destined to somewhere, that without such belief there could be no prayer, no meditation, no peace, and no happiness.”123

Spirituality is something that provides hope, connection with others, and reason or meaning of existence for many (if not most) people. It is amazing that the medical community has been slow to accept the power of spirituality because this is an area that gives meaning to so many peoples’ lives. Spirituality has been linked to health perception, a sense of connection with others, and well-being.66,67,124–130

Anything that helps the client put the disability into perspective and helps the client move on with life in a healthy way is good. The Western medical system was based on diagnosis of pathology and how best to cure disease, but there has been a slow but fruitful shift toward a more holistic view of the healing process and prevention. The National Institutes of Health now has a National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (http://nccam.nih.gov). Almost every major hospital and university in the country now has an integrative health center (e.g., http://stanfordhospital.org/clinicsmedServices/clinics/complementaryMedicine and www.osher.hms.harvard.edu). Although this small but steady shift in the focus of medicine has gained momentum, one of the dangers of the medical system is still the entrapment in pathology to the point where the client may not see anything but his or her pathology. Spirituality can help the client and the family to see that there is more to life than pathology, stimulate interaction with others, put the functional limitations in perspective, give meaning to life (and the disability), and give the person hope and a sense of well-being.* This is what we all want for the client and the family. Refer to Chapters 1, 5, and 39 for additional content.

Adjustment using the stage concept

Each person has his or her own coping style, and each should be allowed to be unique. Kerr133 describes five possible stages of adjustment:

Shock: “This really isn’t happening to me.”

Expectancy for recovery: “I will be well soon.”

Defense: “I will live with this obstacle and beat it.” (healthy attitude) “I am adjusted, but you fail to see it.” (neurotic attitude)

Adjustment: “It is part of me now, but it is not necessarily a bad thing.”

In light of current research, it is important for the therapist to realize that these are not lockstep stages and are to be thought of as concepts to help with the understanding of common reactions of all individuals.134,135 Some individuals may settle in one stage for quite some time or may even skip stages altogether, whereas others may move through the stages quickly. This is an incredibly individual process.

Mourning

During the stage of mourning the individual feels that all is lost, that he or she will never achieve anything in life. Suicide is often considered. The individual may feel that characteristics of the personality (such as courage or will) have also been lost and must be mourned as well. Thus, motivation to continue therapy or the will to improve may be impeded. The prospect of total recovery may no longer be held, but at the same time there appears to be no other acceptable alternative. This feeling of despair may be expressed as hostility, and as a result therapists may view the individual as a “problem patient.” It is possible for a client to remain at this stage with feelings of inadequacy, dependence, and hostility. However, it is also possible for therapeutic intervention to facilitate movement to the next stage by creating situations in which the client may feel that “normal” aspirations and goals can be achieved. In this circumstance, normal would not include such “low-level” activities as dressing or walking; these are all activities that were taken for granted before the injury. Normal, though, would include performing the job the client was trained to do. Such activities would also include playing with or caring for a child or family. This would be seen as self-actualization by Maslow.136

Adjustment

In the final stage, adjustment, the person sees the disability as neither an asset nor a liability but as an aspect of the person, much like a large nose or big feet. He or she is accepting what is, not resisting what is. Functional limitation or inability to participate in any life activity is not something to be overcome, apologized for, or defended. Kerr133 refers to two aspects or goals of this stage. The first goal is for the person to feel at peace with his or her god or greater power: the client does not feel that he or she is being punished or tested. The second goal is for the client to feel that he or she is an adequate person, not a second-class citizen. Kerr137 believes that “It is essential that the paths to those more ‘abstract goals’ be structured if the person is to make a genuine adjustment.” She also believes that it is the health care professional’s job to offer that structure.

Acceptance or adjustment is at least as hard to achieve and maintain in life for the disabled person as happiness and harmony are for all people.138 Adjustment connotes putting the disability into perspective, seeing it as one of the many characteristics of that person. It does not mean negating the existence of or focusing on the condition. Successful adjustment may be defined as a continuing process in which the person adapts to the environment in a satisfying and efficient manner. This is true for all human beings, able-bodied or disabled. There are always obstacles to overcome in attempting the goal of a happy and successful life.16,92,138,139

White140 stated that without some participation, there can be no affecting the environment and thus no sense of self-satisfaction. Fine141 and King142 point out that without satisfaction from affecting the environment, reinforcement is insufficient to carry on the behavior, and the behavior will be extinguished. Thus satisfaction and performance must be linked. If the patient has not adjusted to his or her new body, however, little satisfaction can be gained from such everyday activities as walking, eating, or rolling over in bed.143 To define adjustment on a purely performance basis is to run the risk of creating a “mechanical person” who might be physically rehabilitated but, once discharged, may find that he or she lacks satisfaction, incentive, and purpose. The psychological state of adjustment is what makes self-satisfaction possible.

Body image

“Self-care is never a selfish act—it is simply good stewardship of the only gift I have, the gift I was put on this earth to offer to others. Anytime we can listen to true self and give it the care it requires, we do so not only for ourselves but for the many others whose lives we touch.”121

Body image is an all-encompassing concept that looks at how the person and to some extent the support systems view the person and roles that are expected to be assumed. Taleporos and McCabe20 found that clients had negative feelings about their bodies and general negative psychological experiences after injury. Even when clients do not have disfigurements that are readily observable, they often still report changes in body image and negative feelings of self-worth.

One of the issues that may arise relating to body image is sexuality. This concept may take many behavioral forms: flirting, harassment, questions about fertility, or questions regarding whether the client is capable of performing the sex act at all. Flirting may be a sign that clients have had assaults on their femininity or masculinity. By flirting, clients are often trying to determine whether they still are seen as a sensual being. In this case the therapist may need to set boundaries by saying that he or she is not allowed to date or flirt with clients. This is to make sure that the client does not think that it is something about the disability that is the “turnoff.” Sensitivity must be used because the client could think that “if a medical person finds me repulsive then no one will ever see me as attractive.” It is important for the therapist to try to ascertain the intent behind the behavior. Usually this can be accomplished by evaluating how he or she feels about the interaction. If the therapist feels unthreatened and does not feel demeaned when the client is flirting, he or she still needs to report this to the therapist of record. If the therapist feels defensive, demeaned, or very uncomfortable, then he or she may be experiencing harassment. It is never warranted or “part of the job” to be harassed, and the client’s behavior must be stopped immediately by alerting the client that the behavior is making the therapist feel uncomfortable and that it must stop now. Again, the therapist needs to go to the supervisor or team to mention this behavior. It can often be the case that other team members are experiencing the same behavior and it can be dealt with as a team. If the behavior is considered a chronic problem by the team, a treatment plan needs to be designed to stop the behavior. It is important to remember that sexual health should not be a neglected area of client treatment. It may take time for the appropriate questions to be asked by the client.28,144–148

Questions about any physical performance are within the domain of therapy. If the client is asking for information regarding sex (e.g., positioning options) it is a subject that needs to be addressed in a respectful manner. If the questions are regarding fertility, capability, and the like, then these should be referred to an appropriate medical person. None of these questions should be discouraged or neglected, because this area is important for your clients’ motivation and sexual health.149,150 It is important for the therapist to know that in spinal cord injury, fertility will generally not be impaired for a woman, but issues of lubrication before sex should be addressed by the appropriate person. Men may have erection problems and ejaculation issues, but these too can be addressed by the appropriate person. It is now known that fertility in spinal cord–injured men may be possible and should not be ruled out.146,151–154

Awareness of sexual issues

Sexuality is usually one of the last areas to be assessed by clinical staff, but it is one area mentioned as having great importance to family members and the client.83,104,155,156 Sexuality involves more than just the sex act; it incorporates characteristics such as sexual attraction, sexual identification, sexual confidence, and sexual validation.104,155,156 It is a predictor of adjustment to disability, of success in vocational training, and of marital satisfaction when the woman is disabled.28,73,147,148,156–162

Sexuality (sensuality) is representative of how the person is dealing with his or her world. If the person feels inadequate as a sexual, sensual, and lovable human being, there is little chance that the person will also feel motivated to pursue other avenues of life.83,156,163 This area of function must be assessed with great sensitivity to the individual’s feelings.143,148,163–165

Development of sensuality (sexuality)

Even before birth, the sense of touch166 and the ability to distinguish pleasurable and unpleasurable tactile sensations begin to develop. Pleasurable feelings are comforting, and attempts are made to prolong them; for example, a baby cries when nursing is stopped. If satisfaction is not derived from this interaction on a regular basis, a feeling of anxiety may develop, the child may withdraw from interaction with others, and distrust may develop.166 If pleasure in interaction with others is obtained in the first 3 years, the ability to maintain the warmth of being close and being nourished is translated into trust (that all needs will be satisfied by the caretaker) and lovability (bonding). It is here that a sense of intimacy is initiated.106,167 By the age of 5 years, the ability to explore the world by using the hands and mouth, as well as other parts of the body, allows the individual to develop communication, self-gratification, and a feeling of competence.106,140,167

This feeling of competence is derived from the effective use of the body to meet its needs and to accomplish tasks. By the age of 8 years, body parts and body processes are usually named and the child perceives the body as good. At this time intimacy between the self and another person is further refined, as are roles. During puberty, body changes and sexual tension are heightened. Self-acceptance is based on the person’s perception of how effectively he or she has accomplished the previous tasks.106,167–169

Pediatric sensuality

The therapy session should also help the client develop a sense of personal ownership of the body.81,155,170 This aspect is often neglected when working with children.81,167 The therapist often does not ask permission to touch a client, thus suggesting that the client lacks the right to control being touched by others. The last thing the therapist would desire to communicate, especially to a child, is that any person has the right to handle and touch the client’s body. Child molestation with a disabled population is just beginning to be recognized as a problem in this country, with possibly one third of the female and male population being victimized.81 It is hard to think of a more likely victim than a person who has (unintentionally) been taught that he or she does not have the right to say “No” to being touched and who cannot physically resist unwanted advances and in some cases cannot even communicate that abuse has taken place. The effects of this can be seen in adults. When one client was asked why tone increased in her lower extremities when she was touched, her response was, “I was sexually abused by my father in the name of therapy, and therapy and sexual abuse are synonymous at this point.” No wonder she had not wanted to reenter therapy!

One way of helping clients “own” their respective bodies (besides asking permission to touch) is by naming body parts and body processes using correct terminology (as opposed to baby talk), thus making it possible for the client to communicate and relate appropriately.81,167,170,171 This can be accomplished as the need arises, or it can be encouraged through the use of anatomically correct puzzles or dolls during therapy sessions.

One goal of therapy may be to develop the concept that the body (in the case of persons with the congenital disabilities) or the “new body” (in the case of those with acquired disabilities) is acceptable and good,167–171 thus giving the client a more positive attitude toward his or her body and toward therapy. Pointing out a particularly positive aspect of the client’s body and mentioning this regularly can encourage this attitude. This feature could be the hair, the eyes, or a smile, but it should be an aspect of the client that can be seen and commented on by others as well. Commenting on how well the body feels when it is relaxed or how good the sun feels on the body helps the client recognize that the body can be a positive source of pleasure.

Another message that can negatively affect the client in later life is the concept that individuals with movement dysfunction are asexual and will never have sexual needs or partners.73,148,169–173 Although it may not be appropriate to deal directly with the concept in therapy with a child, the therapist might mention that he or she knows of a person with a functional problem such as the client’s movement limitations who is married or who has children. In this way the therapist communicates that there is a possibility that the “normal” sex roles of the child may be fulfilled in the future. Without this possibility being presented, the child may think that there is no chance that all the movies, books, and television programs that deal with normal adult interactions apply to individuals with functional limitations, a belief that leads to poor socialization and further alienation from participating in life.*

Adult sexuality

The client may feel that his or her sexual identity is threatened by a newly acquired disability and may try to assert sexuality through jokes, flirting, or even passes toward the therapist. In these cases it is important for the therapist to realize that what is often being looked for is the confirmation that the client is still a sexual and sensual human being; thus the therapist’s response is very important.106,170,171,173,174 If the therapist rejects or even ridicules the client, it may be a very long time before the client can even think of attempting such a confirmation of personal attractiveness. The client may feel that because the therapist rejects the client and the therapist is familiar with the disabled, there is little chance anyone who is not familiar with the disabled could accept the client as lovable.175 The therapist should not be surprised by such advances and should deal with the situation in a professional manner. The therapist should also realize that approximately 10% of the population is homosexual and be prepared for advances from clients of the same sex. The therapist needs to be as professional as possible in acknowledging this client as with any other. All of the therapist’s interactions should be directed toward creating an environment that will promote a stronger and more well-adjusted client.106,170,171,173

The therapist’s response to sexual advances must be tempered with an understanding of the possible cause for the behavior. The client may be cognitively impaired and may not even be aware of the inappropriateness of some forms of sexual behavior, or the client may be trying to control others through acting-out behaviors. The client may have been sexually aggressive even before the injury. At no time should the therapist allow himself or herself to be sexually harassed. If the therapist feels harassed, the therapist must take control of the situation and find a way to stop the client’s behavior. This is usually achieved by confronting the issue. Not dealing with inappropriate behavior will allow it to continue and may be detrimental to the medical team and to the client’s normal participation in life.145,156,170,171

The therapist can assist the client in moving through the stages of self-awareness to appreciate that the client is still sensual, sexual, and huggable. This process can be done through everyday interaction; it may entail encouraging the family to embrace the client and may even call for the therapist to role model these behaviors at times.174 The therapist may provide reading materials to the client and family directly by reviewing and answering questions or indirectly by having such books as Reproductive Issues for Persons with Physical Disabilities,175 Sexuality and the Person with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Guide for Families,176 and Sexual Function in People with Disability and Chronic Illness177 available for their reading. In this way, the individual and significant others are made aware of possible options for the expression of intimacy and of the fact that this part of life is not over.

Because the therapist is in a situation of one-to-one treatment involving touching, moving, and handling the client’s body, he or she may frequently be the natural person from whom the individual may seek information. If this natural curiosity does not appear to be forthcoming, however, the therapist can give the client an opening. For example, during an evaluation of motor skills, the person may be asked if there are any problems in such areas as sexual positioning. The topic need not be pursued any further by the therapist, but when the client is ready to deal with the subject area, he or she will probably remember that the therapist brought it up and may be a person to approach when dealing with these issues.163,170,178

It is important for the therapist to be aware of some of the aspects of sexuality that may or may not affect the client as a result of trauma or disease. Fertility is seldom affected in women.179–183 Men, on the other hand, may experience dysfunction of the penis and testicles and/or fertility.55,69,184–186

Devices may be used and adapted to allow for sexual gratification of the client (masturbation) or significant others. Stimulant drugs such as sildenafil citrate (Viagra) or other aids may be used to enhance a person’s sex life. Sensation should be checked and sexual activities modified (or the client should be alerted to the problem) to avoid breakdowns or medical complications. Positioning modifications may be needed to allow for better energy conservation, joint protection, motor control, maintenance of muscle and skin integrity, and pleasure. Clients may have questions regarding modifications that may be needed for the use of birth control devices or contraindications regarding the use of such devices. Clients may also need equipment (e.g., vibrators) modified if hand function is involved. Complications that may affect function and mobility of the client may arise as a result of pregnancy. Delivery may present some unique situations that may also need to be addressed. After delivery the disabled parent may require modifications to the wheelchair, or consultations may be needed to achieve an optimal level of function in the parenting role. All of these possibilities point to the fact that sexual issues must be dealt with throughout the treatment of all individuals with disabilities, whether the functional limitations are progressive, stable, or correctable.175,179,187 The therapist may approach these needs or aspects of function while taking a client’s sexual history. Clients have repeatedly called for more attention to be paid to sexual concerns. This is not sex counseling or therapy, and the therapist should not try to deal with deep psychosexual issues. The therapist must be informed and needs to provide information that relates to the therapist’s areas of expertise, especially because other medical personnel may not have the knowledge to correctly analyze the components of some of these activities.45,55,69,175,182,183,188–190

Support system

Earlier literature hinted that partner relationships may be negatively affected by a member being disabled. Within the last few years this concept has been questioned in regard to some disabilities such as adult-onset spinal cord injuries,189 whereas pediatric spinal cord injury and other disabilities may result in relationship problems.191,192 It has been shown that adjustment and quality of life can be adversely affected by the physical environment being inadequate, thus making the person more dependent. The result of the dependence appears to be poor relationships.193–195 This can also be seen with the families in which a member has had a brain injury.196,197 In studies on muscular dystrophy it was found that physical dependence is not the only variable needing to be considered. Psychological issues need to be identified and considered as part of intervention.198,199 Recent literature has identified a number of elements that the client and the family may need help to work on, such as “to assist them to develop new views of vulnerability and strength, make changes in relationships, and facilitate philosophical, physical and spiritual growth.”198 Turner and Cox198 also felt that the medical staff could facilitate “recognizing the worth of each individual, helping them to envision a future that is full of promise and potential, actively involving each person in their own care trajectory, and celebrating changes to each person’s sense of self.”198 Man199 observed that each family copes differently in relation to a brain-injured family member and that the family’s structure should be explored to develop intervention guidelines. It has also been noted that health care professionals should view the situation from the family’s perspective to approach and support the family’s adaptation.200 This should be done to help the client and the family accept the disability but at the same time to help them keep the negative views of society in perspective.70 In general, it has also been found that family support is a significant factor in the client’s subjective functioning201,202 and that social engagement is productive.89,203 According to Franzén-Dahlin, Larson, and colleagues,204 enhancing psychological health and preventing medical problems in the caregiver are essential considerations to enable individuals with disabilities to continue to live at home. Their research found that evaluating the situation for spouses of stroke patients was an important component when planning for the future care of the patient.

It should always be noted by the medical establishment that having a disability is expensive in ways that we are often not aware of. There are the obvious medical costs of therapy, surgery, drugs, wheelchairs, or orthoses, but there are other costs such as the possibility of extra cost of transportation, catheters for urination, wheelchair maintenance, adaptive clothing, and the like that are continuing costs not covered by most insurance plans. These costs add up and contribute to the emotional costs and demands on the family. The significant others may feel the need to work more to have the money to cover such expenses, but then that person is not around to help out. This is but one of the many dilemmas that must be acknowledged for the support system of the disabled person. The family may be encouraged to contact such groups as the Family Caregiver Support Network (www.caregiversupportnetwork.org) to get information and assistance with such diverse topics as being a caregiver, legal and financial aid, and communications (this group tends to focus on the adult but still may be a wonderful aid). Such groups will give information to all who need it and help to empower the family. This takes the focus off of the medical condition and may help the family to gain a better, more balanced perspective on the condition.

Loss and the family

In this chapter the client’s support system is referred to as the family. The family may be composed of spouses, parents, children, lovers (especially in gay and lesbian relationships), friends, employers, or interested others such as church groups, civic organizations, or individuals. The people in the support system may go through the same stages of reaction and adjustment to loss that the client does.1,9,141,205–207

Family needs

During this phase, the family network will be in a state of crisis.9 New roles will have to be assumed by the family members, and the “experts” will not even tell them for how long these roles must be endured. If children are involved, they will probably demand more attention to reassure themselves that they will remain loved. Depending on the child’s age, the child will have differing capabilities in understanding the loss (see the section on examination of loss). Each member of the family may react differently to bereavement, and each may be at a different stage of adjustment to the disability (see the section on adjustment). One member may be in shock and deny the disability, whereas another member may be in mourning and may verbalize a lack of hope. The family crisis that is caused by a severe injury cannot be overstated.98,206–209

Role changes in the family may be dramatic.64,74,92,210–212 Members who have never driven may need to learn that motor skill; one who has never balanced a checkbook may now be responsible for managing the family budget; and those who have never been assertive may have to deal forcefully with insurance companies and the medical establishment.9,57,173,213,214

The family may feel resentment toward the injured member. This attitude may seem justified to them because they see the person lying in bed all day while the family members must take over new responsibilities in addition to their old ones. In a study by Lobato, Kao, and Plante,215 Latino siblings of children with chronic disabilities were at risk for internalizing psychological problems. The medical staff may not always understand the stress that family members are under and may react to the resentment expressed either verbally or nonverbally with a protective stance toward the client. Siding with the “hurt” client may alienate the family from the medical staff and may also drive a permanent wedge between family members. This long-term situation may undermine the compliance of family members’ involvement in home programs and ultimately the successful outcome of long-term intervention.

Parental bonding and the disabled child

The parental bonding process is complicated and is still being studied.48 The process may start well before the child is even conceived. The parents often think about having a child and plan and fantasize about future interactions with the child; after conception the planning and fantasizing increase. During the pregnancy the mother and father accept the fetus as an individual, and after the birth of the child the attachment process is greatly intensified. The “sensitive period” is the first few minutes to hours after the birth. During this time the parents should have close physical contact with the child to strongly establish the attachment that will later grow deeper.216,217 There is an almost symbiotic relationship between mother and child at this time: infant and mother behaviors complement each other (e.g., nursing stimulates uterine contraction). It is important at this point for the child to respond to the parents in some way so that there is an interaction. In the early stages of bonding, seeing, touching, caring for, and interacting with the child allow for the bonding process. When this process is disturbed for any reason, such as congenital malformations or hospital procedures for high-risk infants, problems may occur later.

When the parents are told that their child is going to be malformed or disabled, it is a massive shock. The parents must start a process of grieving. The dream of a “normal” child must be given up, and the parents must go through the loss or “death” of the child they expected before they can accept the new child. Parents often feel guilty. Shellabarger and Thompson218 state that parents feel the deformed child was their failure.1 The disabled child will always have a strong impact on the family, sometimes a catastrophic one.1,8,9,218,219 A study by Ha, Hong, Seltzer, and Greenberg220 found that compared with parents of nondisabled children, parents of disabled children experienced significantly higher levels of negative affect, poorer psychological well-being, and significantly more somatic symptoms. Older parents were significantly less likely to experience the negative effect of having a disabled child than younger parents.

In a study by Arnaud, White-Koning, and colleagues221 greater severity of impairment was found to not always be associated with poorer quality of life; in the moods and emotions, self-perception, social acceptance, and school environment domains, less severely impaired children appeared to be more likely to have poor quality of life. Pain was associated with poor quality of life in the physical and psychological well-being and self-perception domains. Parents with higher levels of stress were more likely to report poor quality of life in all domains, which suggests that factors other than the severity of the child’s impairment may influence the way in which parents report quality of life.

Parents must be encouraged to express their emotions, and they must be taught how to deal with the issues at hand. Techniques for accomplishing these goals are discussed in later sections.48,217,219

The child dealing with loss

If a parent is injured, the young child may experience an overwhelming sense of loss. Child care may be a problem, especially if the primary caregiver is injured. The child will probably feel deserted by the injured parent and may demand the attention of the remaining parent. This will increase the strain on all family members.64

The hospital setting is threatening to all people, but children are especially susceptible to loss of autonomy, feelings of isolation, and loss of independence. Senesac (see Chapter 12) has stated that the severity of the disability is not as important a variable in the emotional development of the child as are the attitudes of parents and family.2,8 Parents must attempt to be aware of the child’s inability to understand the permanence (or transience) of the loss of function.8 They will also need to help the child feel secure by bringing in familiar and cherished objects. A schedule should be established and kept to promote consistency. Play and art should be encouraged, especially types that allow the child to vent feelings and deal with the new environment. Any procedures or therapies should be presented in a relaxed and playful way so that the child has time to think and to feel as comfortable as possible about the change. The parents may often need to be reminded to pay attention to the children in the family without disabilities during this acute stage.

The adolescent dealing with loss

The adolescent is subject to all of the feelings and fears that other clients express. Adolescents are in a struggle to achieve autonomy and independence, and they often are ambivalent about these feelings. When an adolescent is suddenly injured and has to cope with being disabled, it can be a massive assault on the individual’s development.139,222 According to research conducted by Kinavey,50 findings imply that youth born with spina bifida face biological, psychological, and social challenges that interfere with developmental tasks of adolescence, including identity formation. Therapists are urged to direct intervention toward humanizing and emancipating the physical and social environment for youth with physical disabilities to maximize developmental opportunities and potential while fostering positive identity.