26 Psychological Symptoms

As I stand in the night the fear approaches

I stand strong and face it with all I have

I stand my ground and face whatever it comes at me with

It reaches to the darkest part of my soul

It flows through me and never seems to go away

For the hopes of the end and of something better

I stand strong for the things that help me fight it

In the end it does not end but I still stand strong

Into the night I stand bold till the end

But then there is another journey ahead

I will face sadness, humiliation, opinion, pain, disgrace, and choice as they tear me apart.

The medicine from friendship, family, love, and life experiences heal me.

—Derick Mount, whose osteosarcoma was diagnosed at age 12. (12/3/1986–8/17/2005)

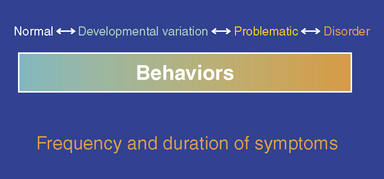

Symptoms such as anxiety and depressed mood are evaluated on a continuum (Fig. 26-1). In general, increasing frequency of a symptom, lasting longer than two continuous weeks, and the presence of significant impairment in functioning or the expressed desire for death should alert clinicians to pursue an in-depth mental health assessment to explore the need for specific psychological intervention. Such assessments must take into account the cultural background of the family, because psychological symptoms may be either minimized or emphasized in certain cultural contexts.1

Anxiety in Pediatric Patients

Anxiety is thought to be problematic when its intensity and duration begin to affect functioning and quality of life, especially in the context of childhood cancer or other life-threatening illness. It can develop as a primary disorder, as a psychological reaction to illness, as a secondary disorder, or may be comorbid with other psychiatric disorders such as depression (Table 26-1). Anxiety may be acute or chronic. It is important to identify any underlying treatable medical etiologies for new onset anxiety (Box 26-1). For example, akathesia, a common side effect of medications, may be misdiagnosed as anxiety.

| Diagnosis | Key symptoms and/or considerations |

|---|---|

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Excessive worry with associated restlessness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, sleep disturbance |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Obsessive preoccupation or fears about physical illness |

| Acute Stress/ post-traumatic stress disorder | Numbness, intrusiveness and hyperarousal; diagnosis depends on duration greater than one month; can occur as a reaction to hearing diagnosis, aspects of medical treatment, or memories of treatment; common in chronic physical illness |

| Separation anxiety disorder | Inappropriate and/or excessive worry about separation from home and/or the family; common in children younger than age 6, resurgence around age 12 |

| Phobias | Specific fear of blood and/or needle, claustrophobia, agoraphobia, white coat syndrome; may lead to difficulty with MRI scans, confinement in isolation, treatment compliance, etc. |

| Panic disorder | Severe palpitations, diaphoresis, and nausea; feeling of impending doom; resulting panic attacks lasting at least several minutes |

| Anxiety disorder caused by general medical condition | Should be considered if history is not consistent with symptoms of primary anxiety disorder/is resistant to treatment; more likely if physical symptoms such as shortness of breath, tachycardia, or tremor are pronounced |

| Substance-induced anxiety disorder | May result from direct effect of substance or withdrawal; particular awareness to medication history, start of new medication, change in dosage |

Adapted and reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR).

BOX 26-1 Possible Medical Conditions Precipitating Anxiety in Medically lll Patients

Adapted and reprinted with permission from the Clinical Manual of Pediatric Psychosomatic Medicine.

2006 American Psychiatric Association.

Anxiety disorders are common in the general population in the United States, with the prevalence of any lifetime anxiety disorder estimated to be 28.8%, with 11 years as the median age of onset.2 Age of onset varies for particular anxiety disorders, with a median onset at 7 years for separation anxiety and phobia disorders, at 13 years for social phobias, and at 19 to 31 years for other disorders. Anxiety is common in children, with a lifetime prevalence of any anxiety disorder at 15% to 20%.3 In children with chronic illness, an estimated 20% to 35 % have an anxiety disorder. In a study assessing anxiety in pediatric oncology patients, 14.3% of 63 children met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder.4 The prevalence of anxiety in other disorders, such as asthma, ranges from 9%5 to 37%,6 while in diabetes anxiety symptoms range from 0.8%7 to almost 20%. One study found anxiety symptoms persisting 10 years after diagnosis of diabetes.8 High rates of anxiety, up to 63%, have been reported in children with epilepsy.9 Clearly, age at onset, sample selection, method and timing of ascertainment of anxiety disorders need to be considered when interpreting the literature on anxiety disorders in chronically ill children.

Post-traumatic stress has emerged as a possible model for understanding cancer-related distress across family members during the illness and beyond.10 Pediatric medical traumatic stress is a set of psychological and physiological responses of children and their families to pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences. Traumatic stress responses include symptoms of arousal, re-experiencing, and avoidance or a constellation of these symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or acute stress disorder.11 Traumatic stress responses are more related to one’s subjective experience of the medical event than its objective severity and are seen in children as well as in parents across the course of treatment and into survivorship.12 Anticipatory anxiety can develop initially or during the course of treatment and clinicians need to monitor vigilantly for increased irritability, resistance, and outright refusal to cooperate with procedures. Many clinicians have found providing anticipatory guidance about normative psychological symptoms, including anxiety and worry about tests, procedures, and hospitalizations, to children and their parents is helpful in decreasing the stress of uncertainty.

Evaluation of anxiety in a pediatric setting

Assessment by a palliative care team member for anxiety begins with a careful medical history including the current subjective symptoms to rule out possible medical conditions precipitating anxiety, such as the use of drugs or alcohol (see Box 26-1). It is critical to evaluate for pain because pain can affect mood and anxiety (see Chapter 22). It is also imperative to ask if the child has a history of anxiety disorders, current or previous use of prescribed medications, or a family history of psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety or mood disorders. It is important to learn about previous anxiety and coping around the initial diagnosis; anxiety surrounding hospitalizations; fear of needles and/or procedures; anticipatory anxiety; or the physical effects of illness. Be specific as to whether there are rooms, people, sights, times during the day, days of the week, sounds or smells that the child finds aversive in order to better understand how to modify these factors. The clinician should be alert to previous difficulties with separation from home and/or other familiar settings or people. Worries about death or dying need to be explicitly questioned, using developmentally appropriate language. Assessment of sources of anxiety such as academic and social impact and financial burden of illness may add important information.

A thorough assessment for an anxiety disorder includes a review of:

Depression in Pediatric Patients

Depression describes transient sad feelings in combination with a sustained low mood leading to impairment in overall functioning and may present with both psychological and physical symptoms. In general, the most prominent symptoms of depression are sadness, dysphoria, and anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure). Depression may exist as a primary disorder, as a psychological reaction to illness, as a secondary disorder to an organic etiology, or may be comorbid with other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety (Table 26-2). Even if patients do not meet diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder, they should still receive appropriate clinical follow-up and continued monitoring.

TABLE 26-2 Depressive Disorders Seen in Medically Ill Children

| Diagnosis | Key symptoms and/or considerations |

|---|---|

| Major depressive episode | Primary mood disorder most often associated with previous psychiatric history. Must exhibit at least 5 symptoms for at least 2 weeks of: persistent depressed mood, anhedonia, irritability, change of weight, change of appetite, sleep disturbance, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness and/or guilt, diminished ability to concentrate, recurrent thoughts of death. |

| Dysthymia | Chronically depressed or irritable mood for at least 1 year that is less disabling than MDD. At least 2 symptoms of: sleep disturbance, fatigue, diminished ability to concentrate, feelings of hopelessness. |

| Adjustment disorder (that is, the adjustment to diagnosis, course, and treatment of illness) | Depressed mood in reaction to medical illness; the most common mood disorder in cancer patients. Symptoms of depression do not meet criteria for major depression but are associated with mildly impaired functioning or shorter duration. |

| Mood disorder caused by general medical condition | Depressed mood, elevated mood, or irritability caused by underlying medical condition; may be one of first symptoms of medical illness. Relationship to significant physical examination and study findings; particular attention to any central nervous system (CNS) lesions in frontal, limbic, and temporal lobes as possible cause. |

| Substance-induced mood disorder | Depression induced by medication, drugs, or alcohol. Usually resolves within 2 weeks of abstinence. Important to note the course of depression in initiation and/or dosage of a medicine (for example, high-dose α interferon). |

| Primary or secondary mania | Manic symptoms as a primary disorder, secondary to medical condition, induced by medication (such as corticosteroids) or toxicity. Symptoms include abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, rapid speech. Patients with brain atrophy or sleep deprivation are more prone. |

| Behavioral considerations | Regression: When stress of illness leads to behavioral regression and manifests as clinginess, social withdrawal, tearfulness, depressed mood. Very common in children and adolescents. Generally resolves after illness and/or hospitalization. |

| Bereavement | Fleeting thoughts of sadness or suicide that are part of normal mourning process. Complicated bereavement, prolonged and more persistent symptoms of mourning, needs to be distinguished from depression. |

Adapted and reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR).

The lifetime prevalence of a major depressive disorder in the general population in the United States is 16.6%. Approximately 2% of school age children and 4% to 8% of adolescents meet criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) with gender differences becoming more apparent with age (females greater than males).2 A meta-analysis estimates a 9% prevalence of depression in chronically ill children and some studies show a lower-than-normal rate of depression in pediatric cancer.13 Generally, studies using clinical interview methodologies, rather than self report, tend to report higher levels of depression. Some large samples have shown no difference in the prevalence of depression in children with other conditions such as asthma,6 while others14 found that 16.3% of youths with asthma compared with 8.6% of youths without asthma met DSM-IV criteria for one or more anxiety or depressive disorders. The prevalence of depression in youth with diabetes is believed to be two to three times greater than in those without diabetes.15 A study8 found that in the 10 years of post-diabetes diagnosis, 27% of the children and adolescents developed depression. Children with complex partial seizures and absence epilepsy are five times more likely to have a mood or anxiety disorder than healthy children.9 Depression, although common, is often unrecognized and untreated in children and adolescents with epilepsy.16 These data taken across chronic illnesses suggest that screening at regular intervals for depression and anxiety should be considered in chronically ill children, but rates may vary with the particular disease group.

At terminal stages of an illness, clinicians can help the child and family work through feelings of loss and should recognize symptoms of depression as part of the grieving process. Whenever possible, it is important to find ways to help children communicate their worries to family or the clinical team, so that the diagnosis of depression or anxiety can be properly made or ruled out. For example, emotional withdrawal should not be confused with depression. Emotional distancing provides the opportunity to conserve energy to focus on a few significant relationships rather than dealing with multiple painful separations.17 In addition, chronic and severe pain is exhausting, and once under control, the child’s distress may improve. Therefore, it is essential that the palliative care team assess for the role that pain and withdrawal might have in depressive symptoms. Yet, as psychiatric symptoms can be reactive to the stresses and disruptions being experienced, a good history that includes knowledge of these conditions can help the palliative care team anticipate problems and provide them with the time to engage additional resources as needed.

One of the most frequent reasons for a psychiatric consult in a pediatric hospital setting is depression, especially within one year of a cancer diagnosis. Pediatric oncologists in the United States commonly prescribe antidepressants. A survey of 40 pediatric oncologists found that half had prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)18 while a review of a children’s hospital reported that 10% of pediatric oncology patients received an antidepressant medication within one year of diagnosis.19 On admission to the NIH Clinical Center, 14% of pediatric oncology patients had been prescribed a psychotropic medication.20 These clinicians appear to be responding to significant distress associated with medical illness and its treatments.

Evaluation of depression in a pediatric setting

Assessment for depression in a child begins with a careful medical history including the current subjective symptoms to rule out possible medical conditions precipitating depression, such as use of drugs or alcohol (Box 26-2; see also Box 26-1). It is critical to evaluate for pain, as significant pain can affect mood and anxiety (see Chapter 22). It is also imperative to ask if the child has a history of mood disorders, previous suicide attempts, current or previous use of prescribed medications, or a family history of psychiatric disorders, especially suicidal behavior. It is useful to elicit a history of prior losses, including serious illness and/or death of family members, parental divorce, loss of pet, disappointments in school or social relationships, and how the child has, until this point, coped with his or her illness.

BOX 26-2 Additional Considerations for Medical Conditions Precipitating Depression in Medically lll Patients

Adapted and reprinted with permission from Abraham J, Gulley JL, Allegra CJ, editors: The Bethesda Handbook of Clinical Oncology, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2005.

Assessment and Management of Suicide in Children and Adolescents

Completed suicide is rare in children. The prevalence is unknown in children with chronic illness because few healthcare professionals assess for suicide risk in pediatric patients presenting with medical complaints.21 Suicide risk increases with age in the general population. Increased rates of suicidal ideation are found in pediatric epilepsy,9 adult survivors of childhood cancer,22 and in adults with medical diagnoses that are also common in childhood such as asthma23 and pulmonary disease.24 Previous studies indicate that chronic physical illness is a risk factor for suicide in adults25,26 and adolescents27 with variability by particular underlying medical diagnoses. There are no pediatric suicide-screening tools that have been validated on a general medical population. Therefore, assessing risk specific to suicide is critical. To provide a comprehensive evaluation, clinicians should inquire about suicidal ideation and history of previous suicide attempts and/or ideation, along with the stated intent and belief of lethality of attempt of suicide with or without a plan. Other risk factors include comorbid psychiatric disorders; symptoms of helplessness, hopelessness, impulsivity; social isolation; uncontrolled pain; advanced disease; male gender; history of abuse or violence; and family history of suicidal behavior or psychopathology.28

Ongoing assessment of suicide risk begins with the first report of suicidal ideation including passive thoughts such as being tired of fighting, or feeling it would be OK not to wake up from sleep. Other specific times for assessment should occur with any change in mental status, during worsening of illness-related symptoms and pain, and at times of management transition such as a change of healthcare provider. Immediate interventions should include environmental restrictions particularly removal of any firearms from the home, appropriate support, observation, and monitoring at home or in the hospital if actively suicidal, with available care providers to be contacted in an emergency. Passive suicidal thoughts should be taken seriously for the distress and possible depression they indicate but may not always require immediate one-to-one monitoring. Specific mental health consultation is essential to further assess suicidal comments even in the medically ill. Treatment must simultaneously address underlying psychopathology, disease-related factors, and pain, and may include psychopharmacology and/or psychotherapy.29

Interventions for anxiety and depression

One of the challenges in evaluating anxiety or depression in children is the differentiation of symptoms that are secondary to the cancer or treatment. Somatic symptoms of depression, such as difficulty sleeping or fatigue, are also common symptoms of both depression and cancer. It is also important to differentiate symptoms that might be interpreted as depression as they may be more accurately an expression of grief. Such symptoms, regardless of whether they are normal rather than pathological require intervention. Therapeutic interventions are designed to reduce distress and to help the child integrate the facets of his or her illness and life into expression.30 For some, talk therapy can provide a vehicle for communication of profound grief. For others, different forms of self-expression are equally powerful and effective including behavioral and cognitive techniques, play, bibliotherapy, storytelling, writing, art, music, and animal-assisted therapy. Most often, a combination of approaches is used.

Behavioral and cognitive behavioral approaches for reducing procedural distress are well established.31 These should be tailored developmentally and include distraction, guided imagery, hypnosis, and relaxation.32 Parents and staff members can be trained in the use of these approaches. Other treatments for anxiety and depression include cognitive behavioral therapy and family therapy to reduce anxiety and provide patients and families with adaptive strategies.

Effective treatment of a depressive disorder is best accomplished in collaboration with a mental health professional. Clinical social workers, psychologists, and/or child psychiatrists familiar with children with serious illness should be consulted in this process. There are few reports of interventions for depression that are specific and exclusive to pediatric cancer or other life-threatening illnesses. Fortunately, literature in this area is growing and the results of more general literatures are relevant. For example, individual psychotherapy for depression, especially cognitive behavioral therapy, is effective for youth in general, both alone and in combination with medication.33 There is less empirically driven data to support other interventions known to be effective in caring for psychological distress in end-of-life care.

Bibliotherapy is an interactive therapeutic intervention that uses literature and storytelling as a means to reduce anxiety, gain insight into behavioral or psychological symptoms, enhance self-understanding, and promote coping skills and personal growth. Stories can shape one’s response to later events, make connections between seemingly random events, address unfair suffering, and provide meaning. After an assessment and the identification of clear therapy goals, the basic technique begins with a therapist choosing a story to read to a child that includes characters the child may relate to and whose struggles and triumphs the child can identify with. The therapist reads the story, followed by a discussion of the themes by the child and the therapist.34,35 The child may be asked to suggest additions or changes in the story, or he or she may share stories that are similar but have different outcomes. Together, the child and therapist might write a book or story that exemplifies the individual child’s struggles, strengths, and gives meaning to his or her life. By externalizing a problem and re-creating endings, children can begin to experience a sense of mastery over their circumstances. An example of a book that addresses cancer, hair loss, courage, and resiliency is Kathy’s Hats, by T. Krisher.

Bibliotherapy is effective in groups as well as in individual sessions. For children able to address end-of-life concerns, reading books, such as The Fall of Freddie the Leaf by L. Buscaglia, The Dream Tree by S. Cosgrove, or Waterbugs and Dragonflies by D. Stickney, allows group participants to talk about their personal thoughts about death, transitions, spiritual concerns, the afterlife, or even to make a book together that has a different ending.36 Viewing films can also be used to impart therapeutic messages and to help the child obtain greater insight into his or her own life circumstances.37,38 The goal of each of these techniques is to foster emotional expressiveness, which in turn, reduces psychic distress.

While most adults use words to express emotions as well as to address conflicts, play is the language and vehicle for a child’s expression and the mechanism for therapists to promote healing. There are a variety of play therapy approaches to reduce the anxiety and depression that critically ill children may experience at the end of life. To create a therapeutic relationship based on trust, safety, and acceptance, a non-directive or child-centered approach during the first few sessions with the child is useful.39 The therapist provides several games, objects, and therapeutic toys the child can choose from. These may be medical play materials such as oxygen masks, alcohol pads, syringes, blood pressure cuff, or stethoscope. Objects that the child can control and can be used to facilitate mastery include play dough, bubbles, finger paints, and sand. Creating an environment of safety and trust that fosters freedom and acceptance is particularly significant for children who often experience a loss of control, privacy, and freedom of choice.

Depending on the child’s health, more directive sessions are useful, particularly when a specific issue needs to be addressed quickly. Children should be told that sometimes he or she gets to choose the therapy activity, and sometimes the therapist will choose. Medical play can be valuable when the child is struggling with specific procedures that can be frightening such as the need for oxygen. Board games created to allow the child to share end-of-life worries, concerns, and fears in a non-threatening and fun way can also be informative and effective in identifying major stressors.40 Because an important goal is to create open communication and closeness between the child and parents, it may be useful to have the parents join the child in playing such games. For the child who may be too ill or weak to play, vicarious enjoyment and expression may be accomplished by playing for the child. Through a nod or by pointing a finger, the child can direct the therapist to roll a die, choose paint colors, or create images that express his or her inner emotional state.36

Writing is another useful medium for working with medically ill children. Anxiety about the unknown is common and therefore, at the end of each session, providing validation of one’s existence and a sense of continuity from one session to the next is useful. Completing a page of a personalized workbook for children living with a life-threatening illness41 or a list of feelings or statements written by both the therapist and child about what activities and feelings were evident that day, can be helpful. A narrative therapy approach of letter writing, postal or e-mail, between sessions can also be used to maintain open communication. A relatively new technique, computer-assisted art therapy,42 can enable online interactive communication between the child and the therapist in real time.

Children often fear that they will be forgotten after death. The workbook and letters written during sessions may be material that the children wish their parents to keep and cherish following their death. “My Mock Will,” a page in the workbook, This Is My World, has been especially instructive for parents who were not able to communicate with their child about his or her last wishes or who the child would like to have some of his or her most meaningful belongings. As death approaches, feelings of loneliness and the need for expression often intensify. Adolescents particularly appreciate the opportunity to use writing techniques to counteract their anxiety, sadness, and grief. This can take the form of a personal narrative, song, poem, or combination of all. Many find that addressing issues such as funeral arrangements, giving away belongings, and discussion of how they wish to be remembered43 less threatening through writing than verbal communication. Offering children the opportunity to use creative writing to document what they would want to happen after they are gone and to leave something of themselves behind can lessen anxiety as it affirms that an important part of their existence is still under their control.

Art therapy is another creative technique to enable children to express their conscious and unconscious concerns and to externalize their fears and anxieties. The use of art media can be used as memory-making or legacy-building activities for the child to do alone or with family members. Treasure boxes, pillow cases, outlining and then painting of a parent and child’s hands touching, and family quilts, especially those that includes photographs, can also be a potent form of self-expression and healing. Photography can be used as a powerful avenue to reduce distress, increase a sense of control, and promote family interactions and communication. Following instructions pertaining to confidentiality, providing a child with a camera and asking him or her to take pictures that will show others what it is like to be sick can provide the family and providers insight into the child’s perspective. Self-portraits are perhaps the most powerful and valuable photos to work with therapeutically. Asking the child to choose where they would like their portrait taken or what they would like to be doing or wearing when their portrait is created allows others to bear witness to what is most important to that child. Using phototherapy techniques, children can connect the past with the present,44 critical steps in integrating their life experience.

The contact comfort of tactile stimulation and the gentle presence of the animal has both physical and psychosocial effects on children.45 Animal-assisted therapy tends to reduce heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration rate, inducing a physiologic relaxation response. Reduction in anxiety and improvement in confidence, self-image and self-esteem has been found.46 Children participating in animal-assisted therapy may also experience a significant reduction in pain, perhaps due to the release of endorphins that occurs during interaction with a friendly animal.47 Additionally, the animal provides a distraction from pain and the hospital experience as well as direct enjoyment. According to a review of articles addressing the healing power of the human-animal connection, the affection shared between the child and animal promotes healing, and provides motivation. Patients also enjoy having a sense of control and a sense of calm when they are able to help care for the animal.45

When anxiety or depression is so severe that the child cannot participate or make use of the psychotherapeutic techniques offered, pharmacologic interventions may need to be considered. Combining pharmacological and psychological interventions is often effective. Before prescribing anxiolytic or antidepressant agents, considerations include knowing the body weight, Tanner staging, and clinical status. Drug-drug interactions should also be factored into medication and dose selection. Benzodiazepines can cause sedation, confusion, and behavioral inhibition, especially in children. Antihistamines are not helpful for persistent anxiety and their anticholinergic properties can precipitate or worsen delirium (Table 26-3). For pharmacologic treatment of depression, both citalopram and fluvoxamine have been shown to be well tolerated in empirical trials in pediatric oncology patients.4,48 Case reports for use of tricyclic antidepressants,49,50 low-dose atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone)51 and low-dose stimulants52 in medically ill children are in the literature. Similarly, there is evidence for family interventions in childhood disorders, including depression.53 Many families may be reluctant to try psychotropic medications for a variety of cultural and personal beliefs. However, they are often more willing to consider them when it is explained, for example, how the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment may be due to a shared biologic mechanism of cytokine-induced mood changes.54,55

TABLE 26-3 Preparations and Dosages of Anxiolytics and Antidepressants in Children

| Formulation/tradename | Prescribing information ‡ (dose ranges) | Clinical information |

|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | Chronic use will lead to tolerance and dependence. | |

| Clonazepam/Klonopin |

* Has an FDA indication in children or adolescents.

‡ Prescribing information adapted from Johns Hopkins Hospital, Custer, Rau, and Lee (eds.). The Harriet Lane Handbook, 18th Edition, Mosby: An Imprint of Elsevier Science, 2008. mg, milligram; kg, kilogram; hr, hour; po, per os or by mouth; IV, intravenous; Max, maximum dose/day; GI, gastrointestinal.

The need for intervention may continue after the end of treatment or throughout critical periods of development in a child with a chronic illness. For adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families, participation in a combined cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and family therapy intervention reduced symptoms of traumatic stress in all members of the family.56,57 Resources for multiinterdisciplinary members of pediatric oncology teams to promote trauma informed practice are in the Medical Traumatic Stress Toolkit58 produced by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and available by download at: www.nctsnet.org/nccts/nav.do?pid=typ_mt_ptlkt.

Parents often question for years to come whether they made the right treatment decisions for their child, about their decision to pursue palliative or aggressive treatment, or even about having conceived or given birth to a child who developed a terminal illness.59 The need to review events over and over, until acceptance or peace comes is common. Some are able to eloquently express these deep emotions and find gratitude for the time they did have, albeit too brief, as the following poem illustrates:

If he had told me “that one day this soul may make my heart bleed,” I still would have chosen you…

Of course, even though I would have chosen you, I know it was God who chose me for you….

Summary

Anxiety and depression are common symptoms in the seriously medically ill child. This chapter has reviewed clinical presentations of anxiety and depression along with means for assessing and treating these symptoms. As the child’s well-being is intrinsically linked to parents’ overall coping and functioning,60 of great importance, regardless of the specific intervention used, is the establishment and maintenance of a developmentally appropriate and supportive therapeutic relationship that involves the family in a meaningful way. These children and their families are eager for help and support. By understanding their worries, concerns, and grief and by building on their strengths throughout the unpredictable course of the illness, tremendous growth, and resilience can shine through the pain of loss and grief.

1 Field M.J., Behrman R.E., editors. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families, Board on Health Sciences Policy (HSP). Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine (IOM), The National Academies Press, 2003.

2 Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., et al. Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593-602.

3 Beesdo K., Knappe S., Pine D.S. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;32:483-524.

4 Gothelf D., Rubinstein M., Shemesh E., et al. Pilot study: fluvoxamine treatment for depression and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1258-1262.

5 Richardson L.P., Lozano P., Russo J., et al. Asthma symptom burden: relationship to asthma severity and anxiety and depression symptoms. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1042-1051.

6 Ortega A.N., Huertas S.E., Canino G., et al. Childhood asthma, chronic illness, and psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(5):275-281.

7 Chavira D.A., Garland A.F., Daley S., et al. The impact of medical comorbidity on mental health and functional health outcomes among children with anxiety disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(5):394-402.

8 Kovacs M., Goldston D., Obrosky D.S., et al. Psychiatric disorders in youths with IDDM: rates and risk factors. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(1):36-44.

9 Caplan R., Siddarth P., Gurbani S., et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2005;46:720-730.

10 Kazak A., Simms S., Barakat L., et al. Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program (SCCIP): a cognitive-behavioral and family therapy intervention for adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families. Fam Process. 1999;38:175-191.

11 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

12 Stuber M.L., Shemesh E. Post-traumatic stress response to life-threatening illnesses in children and their parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin North Am. 2006;15:597-609.

13 Bennett D.S. Depression among children with chronic medical problems: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 1994;19:149-169.

14 Katon W., Lozano P., Russo J., et al. The prevalence of DSM-IV anxiety and depressive disorders in youth with asthma compared with controls. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:455-463.

15 Kokkonen J., Taabuka A., Kokkonen E.R. Diabetes in adolescence: the effect of family and psychologic factors on metabolic control. Nord J Psychiatry. 1997;51:165-172.

16 Plioplys S., Dunn D.W., Caplan R. 10-year research update review: psychiatric problems in children with epilepsy. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2007;46(11):1389-1402.

17 Kubler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

18 Kersun L.S., Kazak A.E. Prescribing practices of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) among pediatric oncologists: a single institution experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:339-342.

19 Portteus A., Ahamd N., Tobey D., et al. The prevalence and use of antidepressant medication in pediatric cancer patients. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16:467-473.

20 Pao M., Ballard E.D., Rosenstein D.L., et al. Psychotropic medication use in pediatric patients with cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:818-822.

21 Habis A., Tall L., Smith J., et al. Pediatric emergency physicians’ current practices and beliefs regarding mental health screening. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23(6):387-393.

22 Recklitis C.J., Lockwood R.A., Rothwell M.A., et al. Suicidal ideation and attempts in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3852-3857.

23 Goodwin R.D., Eaton W.W. Asthma, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts: findings from the Baltimore Catchment Area follow-up. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:717-722.

24 Goodwin R.D., Kroenke K., Hoven C.W., et al. Major depression, physical illness, and suicidal ideation in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:501-505.

25 Ratcliffe G.E., Enns M.W., Belik S.L., et al. Chronic pain conditions and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic perspective. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:204-210.

26 Hughes D., Kleespies P. Suicide in the medically ill. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(Suppl):48-59.

27 Blumenthal S.J. Youth suicide: risk factors, assessment, and treatment of adolescent and young adult suicidal patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1990;13:511-556.

28 Simon R.I., Hales R.E. The American psychiatric publishing textbook of suicide assessment and management. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 2006.

29 Berman A., Jobes D., Silverman M. Adolescent suicide: assessment and intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2006.

30 Sourkes B., Frankel L., Brown M., et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35:350-386.

31 Spirito A., Kazak A.E. Effective and emerging treatments in pediatric psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

32 Power S.W. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: procedure-related pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24:131-145.

33 TADS Team. The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1144.

34 Kreitler S., Oppenheim D., Segev-Shoham E. Fantasy, art therapies, humor and pets as psychosocial means of intervention. In: Kreitler S., editor. Psychosocial aspects of pediatric oncology. Bognor, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2004:351-388.

35 Rokke K. A place for children’s literature in dealing with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1993;10:57.

36 Brown C.D. Therapeutic play and creative arts. In: Armstrong-Daily A., editor. Hospice care for children. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009:305-338.

37 Kalm M.A. The healing movie book—precious images: the healing use of cinema in psychotherapy. Lulu Press, 2004.

38 Wolz B. E-motion picture magic: a movie lover’s guide to healing and transformation. Centennial, Colo: Glenbridge, 2005.

39 Landreth G.L. Innovatizons in play therapy: issues, process, and special populations. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2001.

40 Wiener L. Shop talk: a new therapeutic game for youth living with cancer and other life-threatening illnesses. Psychooncology. 2009;18(Suppl 2):S240-S241.

41 Wiener L. This is my world. Washington, DC: CWLA Press, 1998.

42 Malchiodi C.A. Art therapy and computer technology: a virtual studio of possibilities. London: Jessical Kingsley, 2000.

43 Wiener L., Ballard E., Brennan T., et al. How I wish to be remembered: the use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1309-1313.

44 Weiser J. Phototherapy techniques: using clients’ personal snapshots and family photos as counseling and therapy tools; in memory of Arnold Gassan photographer, poet and phototherapy pioneer—feature. 2009. findarticles.com. Available at: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2479/is_3_29/ai_80757504/ Accessed August 10

45 Halm M.A. The healing power of the human-animal connection. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17:373-376.

46 Willis D.A. Animal therapy. Rehabil Nurs. 1997;22:78-81.

47 Braun C., Stangler T., Narveson J., et al. Animal-assisted therapy as a pain relief intervention for children. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009;15:105-109.

48 DeJong M., Fombonne E. Citalopram to treat depression in pediatric oncology. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:371-437.

49 Maisami M., Sohmer B.H., Coyle J.T. Combined use of tricyclic antidepressants and neuroleptics in the management of terminally ill children: a report on three cases. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24:487-489.

50 Pfefferbaum-Levine B., Kumor K., Cangir A., et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for children with cancer. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;140:1074-1076.

51 Bealke J.M., Meighen K.G. Risperidone treatment of three seriously medically ill children with secondary mood disorders. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:254-258.

52 Walling V.R., Pfefferbaum B. The use of methylphenidate in a depressed adolescent with AIDS. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1990;11(4):195-197.

53 Diamond G., Josephson A. Family-based treatment research: a 10-year update. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:872-887.

54 Cleeland C.S., Bennett G.J., Dantzer R., et al. Are the symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment due to a shared biological mechanism? A cytokine-immunologic model of cancer symptoms. Cancer. 2003;97:2919-2925.

55 Miller A.H., Maletic V., Raison C.L. Inflammation and discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):732-741.

56 Kazak A.E., Alderfer M.A., Streisand R., et al. Treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families: a randomized clinical trial. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18:493-504.

57 Stuber M.L., Shemesh E. Post-traumatic stress response to life-threatening illnesses in children and their parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;15:597-609.

58 Stuber M.L., Schneider S., Kassam-Adams N., et al. The medical traumatic stress toolkit. CNS Spectr. 2006;11:137-142.

59 Worden J.W., Monahan J.R. Caring for Bereaved Parents. In: Arnstrong-Daily A., editor. Hospice care for children. ed 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001:137-156.

60 American Academy of Pediatrics. Family pediatrics: report of the Task Force on the Family. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1541-1571.