Chapter 23 Psychological medicine

Introduction

Epidemiology (Box 23.1)

![]() Box 23.1

Box 23.1

The approximate prevalence of psychiatric disorders in different populations

| Approximate percentage | |

|---|---|

|

Community |

20 |

|

Neuroses |

16 |

|

Psychoses |

0.5 |

|

Alcohol misuse |

5 |

|

Drug misuse |

2 (an underestimate) |

|

(total in community 20% due to co-morbidity) |

|

|

Primary care |

25 |

|

General hospital outpatients |

30 |

|

General hospital inpatients |

40 |

The psychiatric history

As in any medical specialty, the history is essential in making a diagnosis. It is similar to that used in all specialties but tailored to help to make a psychiatric diagnosis, determine possible aetiology, and estimate prognosis. Data may be taken from several sources, including interviewing the patient, a friend or relative (usually with the patient’s permission), or the patient’s general practitioner. The patient interview also enables a doctor to establish a therapeutic relationship with the patient. Box 23.2 gives essential guidance on how to safely conduct such an interview, although it is unlikely that a patient will physically harm a healthcare professional. When interviewing a patient for the first time, follow the guidance outlined in Chapter 1 (see pp. 10–12).

![]() Box 23.2

Box 23.2

The essentials of a safe psychiatric interview

Beforehand: Ask someone of experience who knows the patient whether it is safe to interview the patient alone.

Beforehand: Ask someone of experience who knows the patient whether it is safe to interview the patient alone.

Access to others: If in doubt, interview in the view or hearing of others, or accompanied by another member of staff.

Access to others: If in doubt, interview in the view or hearing of others, or accompanied by another member of staff.

Setting: If safe; in a quiet room alone for confidentiality, not by the bed.

Setting: If safe; in a quiet room alone for confidentiality, not by the bed.

Seating: Place yourself between the door and the patient.

Seating: Place yourself between the door and the patient.

Alarm: If available, find out where the alarm is and how to use it.

Alarm: If available, find out where the alarm is and how to use it.

Components of the history are summarized in Table 23.1.

Table 23.1 Summary of the components of the psychiatric history

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

|

Reason for referral |

Why and how the patient came to the attention of the doctor |

|

Present illness |

How the illness progressed from the earliest time at which a change was noted until the patient came to the attention of the doctor |

|

Past psychiatric history |

Prior episodes of illness, where were they treated and how? Prior self-harm |

|

Past medical history |

Include emotional reactions to illness and procedures |

|

Family history |

History of psychiatric illnesses and relationships within the family |

|

Personal (biographical) history |

Childhood: Pregnancy and birth (complications, nature of delivery), early development and attainment of developmental milestones (e.g. learning to crawl, walk, talk). School history: age started and finished; truancy, bullying, reprimands; qualifications |

|

Adulthood: Employment (age of first, total number, reasons for leaving, problems at work), relationships (sexual orientation, age of first, total number, reasons for endings of relationships), children and dependants |

|

|

Reproductive history |

In women: include menstrual problems, pregnancies, terminations, miscarriages, contraception and the menopause |

|

Social history |

Current employment, benefits, housing, current stressors |

|

Personality |

This may help to determine prognosis. How do they normally cope with stress? Do they trust others and make friends easily? Irritable? Moody? A loner? This list is not exhaustive |

|

Drug history |

Prescribed and over-the-counter medication, units and type of alcohol/week, tobacco, caffeine and illicit drugs |

|

Forensic history |

Explain that you need to ask about this, since ill-health can sometimes lead to problems with the law. Note any violent or sexual offences. This is part of a risk assessment. Worst harm they have ever inflicted on someone else? Under what circumstances? Would they do the same again were the situation to recur? |

|

Systematic review |

Psychiatric illness is not exclusive of physical illness! The two may not only co-exist but may also have a common aetiology |

The mental state examination (MSE)

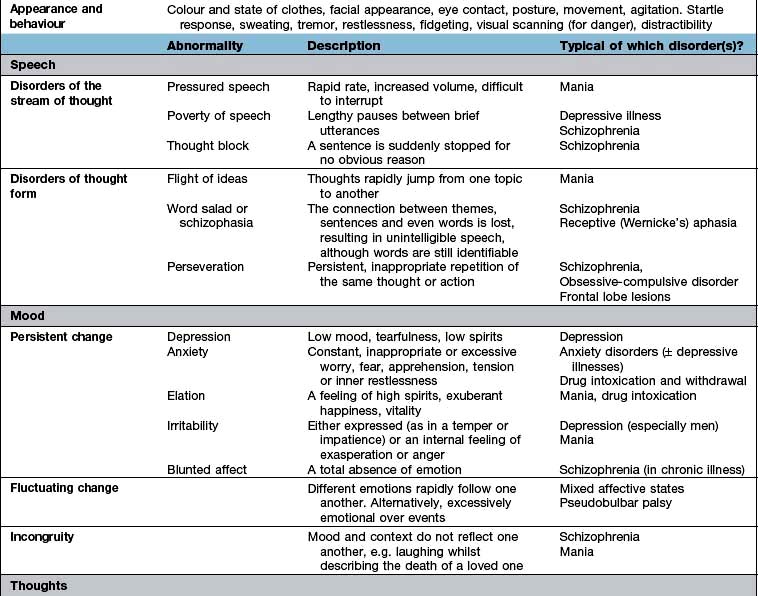

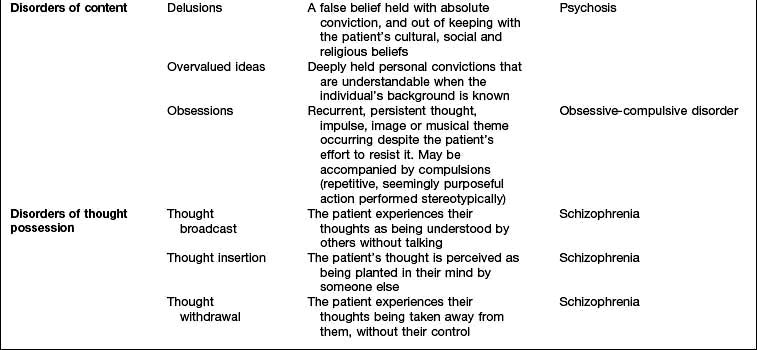

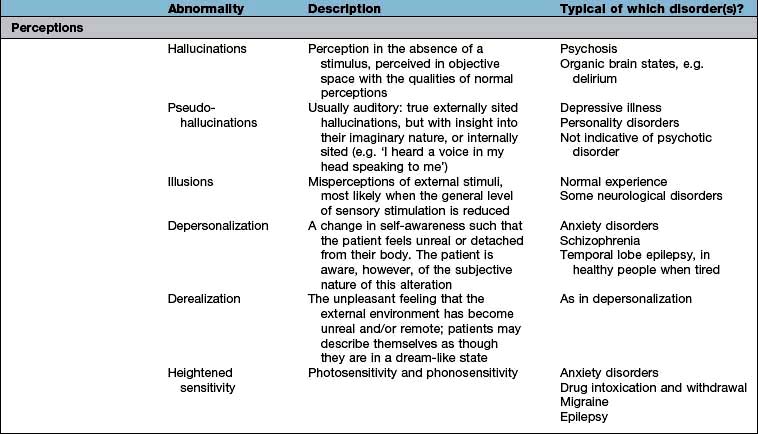

The history will already have assessed several aspects of the MSE, but the interviewer will need to expand several areas as well as test specific areas, such as cognition. The MSE is typically followed by a physical examination and is concluded with an assessment of insight, risk and a formulation that takes into account a differential diagnosis and aetiology. Each domain of the MSE is given below; abnormalities that might be detected and the disorders in which they are found are summarized in Table 23.2. The major subheadings are listed below.

Thoughts

In addition to those abnormalities looked at under ‘speech’ (see above), abnormalities of thought content and thought possession are discussed here. Delusions (Table 23.2) can be further categorized as primary or secondary. Depending on whether they arise de novo or in the context of other abnormalities in mental state.

Cognitive state

Testing can be divided into tests of diffuse and focal brain functions.

Diffuse functions

Orientation in time, place and person. Consciousness can be defined as the awareness of the self and the environment. Clouding of consciousness is more accurately a fluctuating level of awareness and is commonly seen in delirium.

Orientation in time, place and person. Consciousness can be defined as the awareness of the self and the environment. Clouding of consciousness is more accurately a fluctuating level of awareness and is commonly seen in delirium.

Attention is tested by saying the months or days backwards.

Attention is tested by saying the months or days backwards.

Verbal memory. Ask the patient to repeat a name and address with 10 or so items, noting how many times it takes to recall it 100% accurately (normal is 1 or 2) (immediate recall or registration).

Verbal memory. Ask the patient to repeat a name and address with 10 or so items, noting how many times it takes to recall it 100% accurately (normal is 1 or 2) (immediate recall or registration).

Long-term memory. Ask the patient to recall the news of that morning or recently. If they are not interested in the news, find out their interests and ask relevant questions (about their football team or favourite soap opera). Amnesia is literally an absence of memory and dysmnesia indicates a dysfunctioning memory.

Long-term memory. Ask the patient to recall the news of that morning or recently. If they are not interested in the news, find out their interests and ask relevant questions (about their football team or favourite soap opera). Amnesia is literally an absence of memory and dysmnesia indicates a dysfunctioning memory.

Risk

Risk can be broken down into two parts: the risk that the patient poses to themselves and that which they pose to others (Table 23.3). You will have already made an appraisal of risk in your initial preparations for seeing the patient (Box 23.2) and in checking ‘forensic history’ (Table 23.1). It may be necessary to obtain additional information from family, friends or professionals who know the patient – this may save time and prove invaluable.

| Risk to self | Risk to others | |

|---|---|---|

|

Active |

Acts of self-harm or suicide attempts |

Aggression towards others – this may be actual violence or threatening behaviour |

|

Look for prior history of self-harm and what may have precipitated or prevented it |

A past history of aggression is a good predictor of its recurrence. Look at the severity and quality of and remorse for prior violent acts as well as identifiable precipitants that might be avoided in the future (e.g. alcohol) |

|

|

Passive |

Self-neglect |

Neglect of others – always find out whether children or other dependants are at home |

|

Manipulation by others |

Severe behavioural disturbance

Patients who are aggressive or violent cause understandable apprehension in all staff, and are most commonly seen in the accident and emergency department. Information from anyone accompanying the patient, including police or carers, can help considerably. Box 23.3 gives the main causes of disturbed behaviour.

Defence mechanisms

Although not strictly part of the mental state examination, it is useful to be able to identify psychological defences in ourselves and our patients. Defence mechanisms are mental processes that are usually unconscious. Some of the most commonly used defence mechanisms are described in Table 23.4 and are useful in understanding many aspects of behaviour.

| Defence mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

|

Repression |

Exclusion from awareness of memories, emotions and/or impulses that would cause anxiety or distress if allowed to enter consciousness |

|

Denial |

Similar to repression and occurs when patients behave as though unaware of something that they might be expected to know, e.g. a patient who, despite being told that a close relative has died, continues to behave as though the relative were still alive |

|

Displacement |

Transferring of emotion from a situation or object with which it is properly associated to another that gives less distress |

|

Identification |

Unconscious process of taking on some of the characteristics or behaviours of another person, often to reduce the pain of separation or loss |

|

Projection |

Attribution to another person of thoughts or feelings that are in fact one’s own |

|

Regression |

Adoption of primitive patterns of behaviour appropriate to an earlier stage of development. It can be seen in ill people who become child-like and highly dependent |

|

Sublimation |

Unconscious diversion of unacceptable behaviours into acceptable ones |

Classification of psychiatric disorders

Psychiatric classifications have traditionally divided up disorders into neuroses and psychoses.

Neuroses are illnesses in which symptoms vary only in severity from normal experiences, such as depressive illness.

Neuroses are illnesses in which symptoms vary only in severity from normal experiences, such as depressive illness.

Psychoses are illnesses in which symptoms are qualitatively different from normal experience, with little insight into their nature, such as schizophrenia.

Psychoses are illnesses in which symptoms are qualitatively different from normal experience, with little insight into their nature, such as schizophrenia.

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders published by the World Health Organization has largely abandoned the traditional division between neurosis and psychosis, although the terms are still used. The disorders are now arranged in groups according to major common themes (e.g. mood disorders and delusional disorders). A classification of psychiatric disorders derived from ICD-10 is shown in Table 23.5, and this is the classification mainly used in this chapter (ICD-11 will be available in 2014).

Table 23.5 International classification of psychiatric disorders (ICD-10)

FURTHER READING

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. Text Revision (DSM-5). Washington, DC: APA; 2013.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Causes of a psychiatric disorder

Predisposing factors often stem from early life and include genetic, pregnancy and delivery, previous emotional traumas and personality factors.

Predisposing factors often stem from early life and include genetic, pregnancy and delivery, previous emotional traumas and personality factors.

Precipitating (triggering) factors may be physical, psychological or social in nature. Whether they produce a disorder depends on their nature, severity and the presence of predisposing factors. For instance a death of a close, rather than distant, family member is more likely to precipitate a pathological grief reaction in someone who has not come to terms with a previous bereavement.

Precipitating (triggering) factors may be physical, psychological or social in nature. Whether they produce a disorder depends on their nature, severity and the presence of predisposing factors. For instance a death of a close, rather than distant, family member is more likely to precipitate a pathological grief reaction in someone who has not come to terms with a previous bereavement.

Perpetuating (maintaining) factors prolong the course of a disorder after it has occurred. Again they may be physical, psychological or social, and several are often active and interacting at the same time. For example, high levels of criticism at home combined with taking cannabis, as relief from the criticism, may help to maintain schizophrenia.

Perpetuating (maintaining) factors prolong the course of a disorder after it has occurred. Again they may be physical, psychological or social, and several are often active and interacting at the same time. For example, high levels of criticism at home combined with taking cannabis, as relief from the criticism, may help to maintain schizophrenia.

Psychiatric aspects of physical disease

Psychological distress and disorders can precipitate physical diseases (e.g. the cardiac risk associated with depressive disorders or hypokalaemia causing arrhythmias in anorexia nervosa).

Psychological distress and disorders can precipitate physical diseases (e.g. the cardiac risk associated with depressive disorders or hypokalaemia causing arrhythmias in anorexia nervosa).

Physical diseases and their treatments can cause psychological symptoms or ill-health (Table 23.6).

Physical diseases and their treatments can cause psychological symptoms or ill-health (Table 23.6).

Both the psychological and physical symptoms are caused by a common disease process (e.g. Huntington’s chorea).

Both the psychological and physical symptoms are caused by a common disease process (e.g. Huntington’s chorea).

Physical and psychological symptoms and disorders may be independently co-morbid, particularly in the elderly.

Physical and psychological symptoms and disorders may be independently co-morbid, particularly in the elderly.

Table 23.6 Psychiatric conditions sometimes caused by physical diseases

| Psychiatric disorders/symptom | Physical disease |

|---|---|

|

Depressive illness |

Hypothyroidism |

|

Cushing’s syndrome |

|

|

Steroid treatment |

|

|

Brain tumour |

|

|

Anxiety disorder |

Thyrotoxicosis |

|

Hypoglycaemia (transient) |

|

|

Phaeochromocytoma |

|

|

Complex partial seizures (transient) |

|

|

Alcohol withdrawal |

|

|

Irritability |

Post-concussion syndrome |

|

Frontal lobe syndrome |

|

|

Hypoglycaemia (transient) |

|

|

Memory problem |

Brain tumour |

|

Hypothyroidism |

|

|

Altered behaviour |

Acute drug intoxication |

|

Postictal state |

|

|

Acute delirium |

|

|

Dementia |

|

|

Brain tumour |

Factors that increase the risk of a psychiatric disorder in someone with a physical disease are shown in Table 23.7.

Table 23.7 Factors increasing the risk of psychiatric disorders in the general hospital

|

Patient factors |

Setting

Physical conditions

Treatment

Differences in treatment

Uncertainty regarding the physical diagnosis or prognosis, with its attendant tendency to imagine the worst, is often a triggering or maintaining factor, particularly in an adjustment or mood disorder. Good two-way communication between doctor and patient, with time taken to listen to the patient’s concerns, is often the most effective ‘antidepressant’ available.

Uncertainty regarding the physical diagnosis or prognosis, with its attendant tendency to imagine the worst, is often a triggering or maintaining factor, particularly in an adjustment or mood disorder. Good two-way communication between doctor and patient, with time taken to listen to the patient’s concerns, is often the most effective ‘antidepressant’ available.

The history may reveal the role of a physical disease or treatment exacerbating the psychiatric condition, which should then be addressed (Table 23.6). For example, the dopamine agonist bromocriptine can precipitate a psychosis.

The history may reveal the role of a physical disease or treatment exacerbating the psychiatric condition, which should then be addressed (Table 23.6). For example, the dopamine agonist bromocriptine can precipitate a psychosis.

When prescribing psychotropic drugs, the dose should be reduced in disorders affecting pharmacokinetics, e.g. fluoxetine in renal or hepatic failure.

When prescribing psychotropic drugs, the dose should be reduced in disorders affecting pharmacokinetics, e.g. fluoxetine in renal or hepatic failure.

Drug interactions should be of particular concern, e.g. lithium and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Drug interactions should be of particular concern, e.g. lithium and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Sometimes a physical treatment may be planned that may exacerbate the psychiatric condition. An example would be high-dose steroids as part of chemotherapy in a patient with leukaemia and depressive illness.

Sometimes a physical treatment may be planned that may exacerbate the psychiatric condition. An example would be high-dose steroids as part of chemotherapy in a patient with leukaemia and depressive illness.

Always remember the risk of suicide in an inpatient with a mood disorder and take steps to reduce that risk; for example, moving the patient to a room on the ground floor and/or having a registered mental health nurse attend the patient while at risk.

Always remember the risk of suicide in an inpatient with a mood disorder and take steps to reduce that risk; for example, moving the patient to a room on the ground floor and/or having a registered mental health nurse attend the patient while at risk.

Functional or psychosomatic disorders

So-called functional (in contrast to ‘organic’) disorders are illnesses in which there is no obvious pathology or anatomical change in an organ and there is a presumed dysfunction of an organ or system. Examples are given in Table 23.8. The psychiatric classification of these disorders would be somatoform disorders, but they do not fit easily within either medical or psychiatric classification systems, since they occupy the borderland between them. This classification also implies a dualistic ‘mind or body’ dichotomy, which is not supported by neuroscience. Since current classifications still support this outmoded understanding, this chapter will address these conditions in this way.

Because epidemiological studies suggest that having one of these syndromes significantly increases the risk of having another, some doctors believe that these syndromes represent different manifestations of a single ‘functional syndrome’, indicating a global somatization process. Functional disorders also have a significant association with depressive and anxiety disorders. Against this view is the evidence that the majority of primary care people with most of these disorders do not have either a mood or other functional disorder. It also seems that it requires a major stress or the development of a co-morbid psychiatric disorder in order for such sufferers to see their doctor, which might explain why doctors are so impressed with the associations with both stress and psychiatric disorders. Doctors have historically tended to diagnose ‘stress’ or ‘psychosomatic disorders’ in people with symptoms that they cannot explain. History is full of such disorders being reclassified as research clarifies the pathology. An example is writer’s cramp (p. 1122) which most neurologists now agree is a dystonia rather than a neurosis.

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)

Clinical features

Aetiology

Functional disorders often have some aetiological factors in common with each other (Table 23.9), as well as more specific aetiologies. For instance, CFS can be triggered by certain infections, such as infectious mononucleosis and viral hepatitis. About 10% of patients who have infectious mononucleosis have CFS 6 months after the onset of infection, yet there is no evidence of persistent infection in these patients. Those fatigue states which clearly do follow on a viral infection can also be classified as post-viral fatigue syndromes.

Table 23.9 Aetiological factors commonly seen in ‘functional’ disorders

|

Predisposing |

Precipitating (triggering)

Perpetuating (maintaining)

Inactivity with consequent physiological adaptation (CFS and ‘fibromyalgia’)

Avoidant behaviours – multiple chemical sensitivities (MCS), CFS

Maladaptive illness beliefs (that maintain maladaptive behaviours) (CFS, MCS)

Excessive dietary restrictions (‘food allergies’)

Management

The general principles of the management of functional disorders are given in Box 23.4. Specific management of CFS should include a mutually agreed and supervised programme of gradually increasing activity. However, only a quarter of patients recover after treatment. It is sometimes difficult to persuade a patient to accept what are inappropriately perceived as ‘psychological therapies’ for such a physically manifested condition. Antidepressants do not work in the absence of a mood disorder or insomnia.

![]() Box 23.4

Box 23.4

Management of functional somatic syndromes

Stopping drugs (e.g. caffeine causing insomnia, analgesics causing dependence)

Stopping drugs (e.g. caffeine causing insomnia, analgesics causing dependence)

Prognosis

FURTHER READING

White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet 2011; 377:823–836.

White PD. Chronic fatigue syndrome: Is it one discrete syndrome or many? Implications for the “one vs. many” functional somatic syndromes debate. J Psychosom Res 2010; 68:455–459.

Fibromyalgia (chronic widespread pain, CWP)

This controversial condition of unknown aetiology overlaps with chronic fatigue syndrome, with both conditions causing fatigue and sleep disturbance (see p. 1162). Diffuse muscle and joint pains are more constant and severe in CWP, although the ‘tender points’, previously thought to be pathognomonic, are now known to be of no diagnostic importance (see p. 509.) Different specialists have different views.

CWP occurs most commonly in women aged 40–65 years, with a prevalence in the community of between 1% and 11%. There are associations with depressive and anxiety disorders, other functional disorders, physical deconditioning and a possibly characteristic sleep disturbance (Table 23.9). Functional brain scans suggest that patients actually perceive greater pain, supporting the idea of abnormal sensory processing, and this may be in part related to abnormalities in the regulation of central opioidergic mechanisms.

Other chronic pain syndromes

The main sites of chronic pain syndromes are the head, face, neck, lower back, abdomen, genitalia or all over (CWP, fibromyalgia). ‘Functional’ low back pain is the commonest ‘physical’ reason for being off sick long term in the UK (p. 503). Quite often, a minor abnormality will be found on investigation (such as mild cervical spondylosis on the neck X-ray), but this will not be severe enough to explain the severity of the pain and resultant disability. These pains are often unremitting and respond poorly to analgesics. Sleep disturbance is almost universal and co-morbid psychiatric disorders are commonly found.

Aetiology

The perception of pain involves sensory (nociceptive), emotional and cognitive processing in the brain. Functional brain scans suggest that the brain responds abnormally to pain in these conditions, with increased activation in response to chronic pain. This could be related to conditioned behavioural and physiological responses to the initial acute pain. The brain may then adapt to the prolonged stimulus of the pain by changing its central processing. The prefrontal cortex, thalamus and cingulate gyrus seem to be particularly affected and some of these areas are involved in the emotional appreciation of pain in general. Thus, it is possible to start to understand how beliefs, emotions and behaviours might influence the perception of chronic pain (Table 23.9).

Management

Management involves the same principles as used in other functional syndromes (Box 23.4). Since analgesics are rarely effective, and can cause long-term harm, patients should be encouraged to gradually reduce their use. It is often helpful to involve the patient’s immediate family or partner, to ensure that the partner is also supported and not unconsciously discouraging progress.

Specific drug treatments are few:

Nerve blocks are not usually effective.

Nerve blocks are not usually effective.

Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, gabapentin and pregabalin may be given a therapeutic trial if the pain is thought to be neuropathic (see p. 1124).

Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine, gabapentin and pregabalin may be given a therapeutic trial if the pain is thought to be neuropathic (see p. 1124).

Tricyclic antidepressants: The antidepressant dosulepin is an effective treatment in half of the patients who have atypical facial pain, and this effect seems to be independent of dosulepin’s effect on mood. Another tricyclic antidepressant, amitriptyline, is helpful in tension headaches, which might be related to its independent analgesic effect. Amitriptyline has the added bonus of increasing slow wave sleep, which may be why it is more effective than NSAIDs in chronic widespread pain.

Tricyclic antidepressants: The antidepressant dosulepin is an effective treatment in half of the patients who have atypical facial pain, and this effect seems to be independent of dosulepin’s effect on mood. Another tricyclic antidepressant, amitriptyline, is helpful in tension headaches, which might be related to its independent analgesic effect. Amitriptyline has the added bonus of increasing slow wave sleep, which may be why it is more effective than NSAIDs in chronic widespread pain.

Tricyclic antidepressants that affect both serotonin and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) reuptake (e.g. p. 1172) seem to be more effective than more selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, e.g. in neuropathic pain. There is some evidence that tricyclics are generally superior to SSRIs in chronic pain syndromes.

Irritable bowel syndrome

This is one of the commonest functional syndromes, affecting some 10–30% of the population worldwide. The clinical features and management of the syndrome and the related functional bowel disorders are described in more detail in chapter 6. Although the majority of sufferers with the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) do not have a psychiatric disorder, depressive illness should be excluded in people with constipation and a poor appetite. Anxiety disorders should be excluded in people with nausea and diarrhoea. Persistent abdominal pain or a feeling of emptiness may occasionally be the presenting symptom of a severe depressive illness, particularly in the elderly, with a nihilistic delusion that the body is empty or dead inside (see p. 1168).

Management

This is dealt with in more detail in Box 23.4. Seeing a physician who provides specific education that particularly addresses individual illness beliefs and concerns can provide lasting benefit. Psychological therapies that help the more severely affected include:

If indicated, the choice of antidepressant should be determined by the effects of these drugs on bowel transit times, with tricyclic antidepressants normally slowing and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (p. 1172) normally speeding up transit times.

Multiple chemical sensitivity, Candida hypersensitivity, and food allergies

Type 1 hypersensitivities to foods such as nuts certainly exist, although they are fortunately uncommon (approximately 3/1000) (see pp. 68, 69). Direct specific food intolerances also occur (e.g. chocolate with migraine, caffeine with IBS).

Aetiology

Surveys of patients diagnosed with MCS or food allergies have shown high rates of current and previous mood and anxiety disorders (Table 23.9). Eating disorders (p. 1188) should be excluded in people with food intolerances. Some patients taking very low carbohydrate diets as putative treatments may develop reactive hypoglycaemia after a high carbohydrate meal, which they then interpret as a food allergy.

Management

The general principles in Box 23.4 apply. If one assumes a phobic or conditioned response is responsible, graded exposure (systematic desensitization) to the conditioned stimulus may be worthwhile. Preliminary studies do suggest that this approach may successfully treat such intolerances, in the context of cognitive behaviour therapy.

Premenstrual syndrome

Physical symptoms include headache, fatigue, breast tenderness, abdominal distension and fluid retention.

Physical symptoms include headache, fatigue, breast tenderness, abdominal distension and fluid retention.

Psychological symptoms can include irritability, emotional lability or low mood, and tension.

Psychological symptoms can include irritability, emotional lability or low mood, and tension.

The cause of the premenstrual syndrome remains unclear, although exacerbating factors include some of those outlined in Table 23.9. Research suggests that abnormalities of reproductive hormone receptors may play a role.

Management

The general principles in Box 23.4 apply. Treatments with vitamin B6 (p. 210), diuretics, progesterone, oral contraceptives, oil of evening primrose and oestrogen implants or patches (balanced by cyclical norethisterone) remain empirical. Psychotherapies aimed at enhancing the patient’s coping skills can reduce disability. Two trials suggest that graded exercise therapy improves symptoms. Several studies have demonstrated that SSRIs (p. 1172) are effective treatments for the premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

The menopause

The clinical features and management of the menopause are described on page 973. A prospective study has shown that there is no increased incidence of depressive disorders at this time. Such a significant bodily change, sometimes occurring at the same time as children leaving home, is naturally accompanied by an emotional adjustment that does not normally amount to a pathological state.

Somatoform disorders

As explained in the section on functional disorders (p. 1162), the classification of somatoform disorders is unsatisfactory because of the uncertain nature and aetiology of these disorders. However, there are certain disorders, beyond those described in ‘functional disorders’, that present frequently and coherently enough to be usefully recognized.

Somatization disorder

The aetiology is unknown, but both mood and personality disorders are often also present. It is often associated with dependence upon or misuse of prescribed medication, usually sedatives and analgesics. There is often a history of significant childhood traumas, or chronic ill-health in the child or parent, which may play an aetiological role or help to explain difficult therapeutic relationships (Table 23.9). The condition is probably the somatic presentation of psychological distress, although iatrogenic damage (from postoperative and drug-related problems) soon complicates the clinical picture. The course of the disorder is chronic and disabling, with long-standing family, marital and/or occupational problems.

Management of somatoform disorders

The principles outlined in Box 23.4 apply to these disorders. Since they have a poor prognosis, the aim is to minimize disability. Furthermore, it is vital that all members of staff and close family members adopt the same approach to the patient’s problems. The patients often consciously or unconsciously split both medical staff and family members into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ (or caring and uncaring) people, as a way of projecting their distress.

Dissociative/conversion disorders

Clinical features

The various symptoms are usually divided into dissociative and conversion categories (Table 23.10). Dissociative disorders have the following three characteristics that are necessary in order to make the diagnosis:

| Dissociative (mental) | Conversion (physical) |

|---|---|

Other characteristics include:

Symptoms and signs often reflect a patient’s ideas about illness.

Symptoms and signs often reflect a patient’s ideas about illness.

There is usually abnormal illness behaviour, with exaggeration of disability.

There is usually abnormal illness behaviour, with exaggeration of disability.

There may have been significant childhood traumas.

There may have been significant childhood traumas.

Primary gain is the immediate relief from the emotional conflict.

Primary gain is the immediate relief from the emotional conflict.

Secondary gain refers to the social advantage gained by the patient by being ill and disabled (sympathy of family and friends, being off work, disability pension).

Secondary gain refers to the social advantage gained by the patient by being ill and disabled (sympathy of family and friends, being off work, disability pension).

Physical disease is not uncommonly also present (e.g. pseudoseizures are more common in someone with epilepsy).

Physical disease is not uncommonly also present (e.g. pseudoseizures are more common in someone with epilepsy).

Aetiology

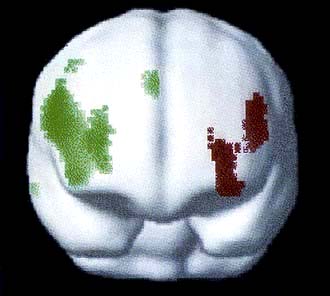

Functional brain scans differ between healthy controls feigning a motor abnormality and people with a similar conversion motor symptom, which suggests that dissociation involves different areas of the brain from simulation (Fig. 23.1). Functional brain scanning of a patient with conversion paralysis has shown that recalling a past trauma not only activated the emotional areas, such as the amygdala, but also reduced motor cortex activity. This would suggest that conversion involves a disinhibition of voluntary will at an unconscious level, so that the patient can no longer will something to happen.

Management

The treatment of dissociation is similar to the treatment of somatoform disorders in general, outlined above and in Box 23.4. The first task is to engage the patient and their family with an explanation of the illness that makes sense to them, is acceptable, and leads to the appropriate management. An invented example of a suitable explanation is given in Box 23.5. Such an explanation would be modified by mutual discussion until an agreed understanding was achieved, which would serve as a working model for the illness. Provision of a rehabilitation programme that addresses both the physical and psychological needs and problems of the patient would then be planned.

A graded and mutually agreed plan for a return to normal function can usually be led by the appropriate therapist (e.g. speech therapist for dysphonia, physiotherapist for paralysis).

A graded and mutually agreed plan for a return to normal function can usually be led by the appropriate therapist (e.g. speech therapist for dysphonia, physiotherapist for paralysis).

At the same time, a psychotherapeutic assessment should be made in order to determine the appropriate form of psychotherapy. For instance, couple therapy will address a significant relationship difficulty; individual psychotherapy could ease an unresolved conflict from childhood.

At the same time, a psychotherapeutic assessment should be made in order to determine the appropriate form of psychotherapy. For instance, couple therapy will address a significant relationship difficulty; individual psychotherapy could ease an unresolved conflict from childhood.

Prognosis

FURTHER READING

olde Hartman TC, Borghuis MS, Lucassen PL et al. Medically unexplained symptoms, somatisation disorder and hypochondriasis: course and prognosis. A systematic review. J Psychosom Res 2009; 66:363–377.

Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A et al. Systematic review of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms and “hysteria”. BMJ 2005; 331:989.

Sleep difficulties

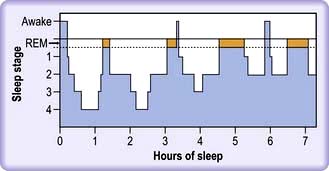

Sleep is divided into rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM sleep:

As drowsiness begins, the alpha rhythm on an EEG disappears and is replaced by deepening slow wave activity (non-REM).

As drowsiness begins, the alpha rhythm on an EEG disappears and is replaced by deepening slow wave activity (non-REM).

After 60–90 minutes, this slow wave pattern is replaced by low amplitude waves on which are superimposed rapid eye movements lasting a few minutes.

After 60–90 minutes, this slow wave pattern is replaced by low amplitude waves on which are superimposed rapid eye movements lasting a few minutes.

This cycle is repeated during the duration of sleep, with the REM periods becoming longer and the slow wave periods shorter and less deep (Fig. 23.2).

This cycle is repeated during the duration of sleep, with the REM periods becoming longer and the slow wave periods shorter and less deep (Fig. 23.2).

Primary sleep disorders include sleep apnoea (p. 818), narcolepsy which responds to tigotine, the restless legs syndrome (Ekbom’s) (see p. 616) and the related periodic leg movement disorder, in which the legs (and sometimes the arms) jerk while asleep.

Psychophysiological insomnia commonly occurs secondary to functional, mood and substance misuse disorders, and when under stress (Box 23.6). It can often be triggered by one of these factors, but then become a habit on its own, driven by anticipation of insomnia and day-time naps.

![]() Box 23.6

Box 23.6

Common causes of insomnia

Initial insomnia (trouble getting off to sleep) is common in mania, anxiety, depressive disorders and substance misuse.

Initial insomnia (trouble getting off to sleep) is common in mania, anxiety, depressive disorders and substance misuse.

Middle insomnia (waking up in the middle of the night) occurs with medical conditions such as sleep apnoea and prostatism.

Middle insomnia (waking up in the middle of the night) occurs with medical conditions such as sleep apnoea and prostatism.

Late insomnia (early morning waking) is caused by depressive illness and malnutrition (anorexia nervosa).

Late insomnia (early morning waking) is caused by depressive illness and malnutrition (anorexia nervosa).

Management of insomnia

Simple measures such as decreasing alcohol intake, having supper earlier, exercising daily, having a hot bath prior to going to bed and establishing a routine of going to bed at the same time should all be tried.

Simple measures such as decreasing alcohol intake, having supper earlier, exercising daily, having a hot bath prior to going to bed and establishing a routine of going to bed at the same time should all be tried.

Relaxation techniques and cognitive behaviour therapy have a role in those with intractable insomnia.

Relaxation techniques and cognitive behaviour therapy have a role in those with intractable insomnia.

Short half-life benzodiazepines can be useful for acute insomnia, but should not be used for more than 2 weeks continuously to avoid dependence.

Short half-life benzodiazepines can be useful for acute insomnia, but should not be used for more than 2 weeks continuously to avoid dependence.

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (zaleplon, zopiclone, zolpidem) act at the benzodiazepine receptors and occasional dependence has been reported.

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (zaleplon, zopiclone, zolpidem) act at the benzodiazepine receptors and occasional dependence has been reported.

Certain antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine and promethazine) and antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, trimipramine, trazodone, mirtazapine) are not addictive and can be used as hypnotics in low dose, with the added advantage of improving slow wave sleep. The commonest side-effects are morning sedation and weight gain.

Certain antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine and promethazine) and antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, trimipramine, trazodone, mirtazapine) are not addictive and can be used as hypnotics in low dose, with the added advantage of improving slow wave sleep. The commonest side-effects are morning sedation and weight gain.

Mood (affective) disorders

Classification

Bipolar affective disorder

Bipolar I disorder is defined as one or more manic or mixed (signs of mania and depression) episodes.

Bipolar I disorder is defined as one or more manic or mixed (signs of mania and depression) episodes.

Bipolar II is defined as a depressive episode with at least one episode of hypomania (this is shorter lived than mania and is not accompanied by psychotic symptoms). Hypomania is noticeably abnormal but does not result in functional impairment or hospitalization.

Bipolar II is defined as a depressive episode with at least one episode of hypomania (this is shorter lived than mania and is not accompanied by psychotic symptoms). Hypomania is noticeably abnormal but does not result in functional impairment or hospitalization.

Bipolar III disorder is less well established and describes depressive episodes, with hypomania occurring only when taking an antidepressant.

Bipolar III disorder is less well established and describes depressive episodes, with hypomania occurring only when taking an antidepressant.

About 10% of patients who have depressive illness are eventually found to have a bipolar illness.

Depressive disorders

Clinical features of depressive disorder

Whereas everyone will at some time or other feel ‘fed up’ or ‘down in the dumps’, it is when such symptoms become qualitatively different, pervasive or interfere with normal functioning that a depressive illness has occurred. Depressive disorder, clinical or ‘major’ depression, is characterized by disturbances of mood, speech, energy and ideas (Table 23.11). Patients often describe their symptoms in physical terms. Marked fatigue and headache are the two most common physical symptoms in depressive illness and may be the first symptoms to appear. Patients describe the world as looking grey, themselves as lacking a zest for living, being devoid of pleasure and interest in life (anhedonia). Anxiety and panic attacks are common; secondary obsessional and phobic symptoms may emerge. Symptoms should last for at least 2 weeks and should cause significant incapacity (e.g. trouble working or relating to others) in order to be dealt with as an illness.

| Characteristic | Clinical features |

|---|---|

|

Mood |

Depressed, miserable or irritable |

|

Talk |

Impoverished, slow, monotonous |

|

Energy |

Reduced, lethargic, lacking motivation |

|

Ideas |

Feelings of futility, guilt, self-reproach, unworthiness, hypochondriacal preoccupations, worrying, suicidal thoughts, delusions of guilt, nihilism and persecution |

|

Cognition |

Impaired learning, pseudodementia in elderly patients |

|

Physical |

Insomnia (especially early waking), poor appetite and weight loss, constipation, loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, bodily pains |

|

Behaviour |

Retardation or agitation, poverty of movement and expression |

|

Hallucinations |

Auditory – often hostile, critical |

In the more severe forms, diurnal variation in mood can occur, feeling worse in the morning, after waking in the early hours with apprehension. Suicidal ideas are more frequent, intrusive and prolonged. Delusions of guilt, persecution and bodily disease are not uncommon, along with second-person auditory hallucinations insulting the patient or suggesting suicide. In severe depressive illness, particularly in the elderly, concentration and memory can be so badly affected that the patient appears to have dementia (pseudodementia). Delusions of poverty and non-existence (nihilism) occur particularly in this age group. Suicide is a real risk, with the lifetime risk being approximately 5% in primary care patients, but 15% in those with depressive illness severe enough to warrant admission to hospital. People with bipolar disorder are also at greater risk of suicide. Screening questions for depressive illness are shown in Box 23.7.

![]() Box 23.7

Box 23.7

Screening questions for depressive illness

During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

During the last month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

During the last month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

During the last month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

If one or both of the answers is ‘yes’, assess further for depressive illness.

Epidemiology

Depressive illnesses are more common in the presence of:

physical diseases, particularly if chronic, stigmatizing or painful

physical diseases, particularly if chronic, stigmatizing or painful

excessive and chronic alcohol use (probably the most depressing drug humans use)

excessive and chronic alcohol use (probably the most depressing drug humans use)

social stresses, particularly loss events, such as separation, redundancy and bereavement

social stresses, particularly loss events, such as separation, redundancy and bereavement

interpersonal difficulties with those close to the patient, especially when socially humiliated

interpersonal difficulties with those close to the patient, especially when socially humiliated

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of depressive illness are shown in Table 23.12. Other psychiatric disorders are the most common misdiagnoses. Some 90% of patients presenting with a depressive illness while misusing alcohol will no longer be depressed 2 weeks after their last drink.

Table 23.12 Common differential diagnoses of depressive illness

|

Other psychiatric disorders |

Organic (secondary) affective illness

Investigations

They will often include measurement of free T4 and TSH (particularly in women), calcium, sodium, potassium, mean corpuscular volume, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, haemoglobin, white cell count, ESR or plasma viscosity

They will often include measurement of free T4 and TSH (particularly in women), calcium, sodium, potassium, mean corpuscular volume, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, haemoglobin, white cell count, ESR or plasma viscosity

Less commonly a chest X-ray, anti-nuclear antibody, morning and evening cortisols, electroencephalogram or a brain scan are indicated.

Less commonly a chest X-ray, anti-nuclear antibody, morning and evening cortisols, electroencephalogram or a brain scan are indicated.

The aetiology of unipolar depressive disorders

Biochemical changes

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Animal studies show it is reduced under stressful conditions.

Animal studies show it is reduced under stressful conditions.

Postmortem studies show reduced concentrations in suicide compared with non-suicide deaths.

Postmortem studies show reduced concentrations in suicide compared with non-suicide deaths.

Adult humans with untreated depressive illness have three times lower concentrations when compared with both healthy controls or those that have received antidepressant treatment.

Adult humans with untreated depressive illness have three times lower concentrations when compared with both healthy controls or those that have received antidepressant treatment.

An integrated model of aetiology

FURTHER READING

Belmaker RH, Agam G. Major depressive disorder. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:55–68.

Frye MA. Bipolar disorder – a focus on depression. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:51–59.

Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 2008; 455:894–902.

Moussavi S, Chatterii S, Verdes E et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007; 370:851–858.

Treatment of depressive illness

The patient needs to know the diagnosis to provide understanding and rationalization of the overwhelming distress inherent in depressive illness. Knowing that self-loathing, guilt and suicidal thoughts are caused by the illness may have an ‘antidepressant’ effect. The further treatment of depressive disorders involves physical, psychological and social interventions (Box 23.8).

![]() Box 23.8

Box 23.8

Management of depressive illness

Physical

Stop depressing drugs (alcohol, steroids)

Stop depressing drugs (alcohol, steroids)

Regular exercise (good for mild to moderate depression)

Regular exercise (good for mild to moderate depression)

Antidepressants (choice determined by side-effects, co-morbid illnesses and interactions)

Antidepressants (choice determined by side-effects, co-morbid illnesses and interactions)

Adjunctive drugs (e.g. lithium; if no response to two different antidepressants)

Adjunctive drugs (e.g. lithium; if no response to two different antidepressants)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (if life-threatening or non-responsive)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) (if life-threatening or non-responsive)

Drugs used in the treatment of clinical depression

As the neurobiology for depressive illness becomes clearer, so too are novel approaches to its treatment; some of the novel targets under active investigation are listed in Box 23.9.

![]() Box 23.9

Box 23.9

Potential targets for novel antidepressant agents

|

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) |

Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone |

General approach to drug treatment of depression

Recreational drugs such as alcohol should be stopped. Prescribed medicines suspected of exacerbating depression, such as corticosteroids, should be gradually stopped or reduced to a safe minimum.

Recreational drugs such as alcohol should be stopped. Prescribed medicines suspected of exacerbating depression, such as corticosteroids, should be gradually stopped or reduced to a safe minimum.

Treatment with antidepressants is more successful when accompanied by sufficient patient education and regular follow-up, particularly a week after starting treatment and throughout the following 6 weeks. Dysthymia responds less well to antidepressants than does a depressive episode.

Treatment with antidepressants is more successful when accompanied by sufficient patient education and regular follow-up, particularly a week after starting treatment and throughout the following 6 weeks. Dysthymia responds less well to antidepressants than does a depressive episode.

The commonest two pharmacological types of antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). All antidepressants have similar efficacy and speed of onset. Choice depends on their side-effects, which can be used to positive effect (sedating drugs given at night to enhance sleep), and their safety. A course of antidepressants should be given until 6 months after recovery from a first episode to prevent relapse. Stopping antidepressants immediately upon recovery leads to a 50% relapse rate within 6 months. The two greatest problems with these drugs are persuading the patient to take them and adherence, since 80% of the UK public wrongly believe that they are addictive.

The commonest two pharmacological types of antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). All antidepressants have similar efficacy and speed of onset. Choice depends on their side-effects, which can be used to positive effect (sedating drugs given at night to enhance sleep), and their safety. A course of antidepressants should be given until 6 months after recovery from a first episode to prevent relapse. Stopping antidepressants immediately upon recovery leads to a 50% relapse rate within 6 months. The two greatest problems with these drugs are persuading the patient to take them and adherence, since 80% of the UK public wrongly believe that they are addictive.

Drug choices in specific circumstances

Recurrent episodes: maintenance treatment with the antidepressant at the dose that obtained remission should be continued for at least 2 years. Maintenance treatment beyond this point should be re-evaluated, taking into account age, co-morbidities and risk factors.

Recurrent episodes: maintenance treatment with the antidepressant at the dose that obtained remission should be continued for at least 2 years. Maintenance treatment beyond this point should be re-evaluated, taking into account age, co-morbidities and risk factors.

Refractory depressive illness: whilst 50% may show response, as few as 30% of individuals (outpatients) get a complete remission with the first choice of antidepressant agent. Strategies available at this point are switching drug classes or augmentation with other agents. This should be overseen by a specialist.

Refractory depressive illness: whilst 50% may show response, as few as 30% of individuals (outpatients) get a complete remission with the first choice of antidepressant agent. Strategies available at this point are switching drug classes or augmentation with other agents. This should be overseen by a specialist.

Psychotic depression needs either a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic drug or electroconvulsive therapy.

Psychotic depression needs either a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic drug or electroconvulsive therapy.

Bipolar depressive illness: monotherapy with quetiapine has been proposed as the drug of choice. Other drugs include mood stabilizers or olanzapine, either alone or in combination with an antidepressant (see p. 1176).

Bipolar depressive illness: monotherapy with quetiapine has been proposed as the drug of choice. Other drugs include mood stabilizers or olanzapine, either alone or in combination with an antidepressant (see p. 1176).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

The most common side-effects of SSRIs resemble a ‘hangover’ and include nausea, vomiting, headache, diarrhoea and dry mouth. Insomnia and paradoxical agitation can occur when first starting the drugs. Adolescents, in particular, may develop suicidal thoughts with SSRIs; only fluoxetine is licensed in the UK for adolescents for this reason. Further studies suggest that this is a small risk, if present, and no study has shown a significant increased risk of suicide itself. One in five patients also has sexual side-effects, such as erectile dysfunction and loss of libido. Uncommon side-effects include restless legs syndrome (see p. 616) and hyponatraemia.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

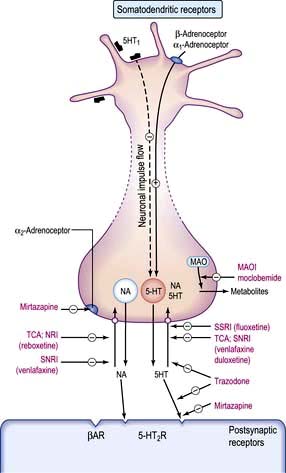

These drugs potentiate the action of the monoamines, noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and serotonin, by inhibiting their reuptake into nerve terminals (Fig. 23.3). Other tricyclics in common use include nortriptyline, doxepin and clomipramine. Dosulepin, imipramine and amitriptyline are the three most commonly used in the UK, but many related compounds have been introduced, some having fewer autonomic and cardiotoxic effects (e.g. lofepramine).

TCAs have a number of side-effects (Table 23.13). In long-term treatment or prophylaxis, weight gain is most troublesome. Because of their toxicity in overdose, it is wisest not to prescribe them to outpatients who have suicidal thoughts without monitoring or giving the drugs to a reliable family member to look after.

|

Antimuscarinic effects |

Convulsant activity |

|

Dry mouth |

Lowered seizure threshold |

|

Other effects |

|

|

Weight gain |

|

|

Cardiovascular |

|

|

QT prolongation |

|

|

Arrhythmias |

|

|

Postural hypotension |

|

Trazodone is different from other tricyclic antidepressants and acts by blockade of 5HT2 receptors.

SNRIs and NRIs

SNRIs: venlafaxine is a potent blocker of both serotonin and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) reuptake (SNRI). It has negligible affinity for other neurotransmitter receptor sites and so produces less sedation and fewer antimuscarinic effects. It can be given in slow-release form with the advantage of once-daily dosage. Nausea is the commonest side-effect and patients should be monitored for hypertension. It should not be prescribed in those with either uncontrolled hypertension or in those prone to cardiac arrhythmias; if an arrhythmia is suspected, it should be ruled out by ECG before starting treatment. Duloxetine works in a similar way to venlafaxine and has been found especially helpful with chronic pain.

SNRIs: venlafaxine is a potent blocker of both serotonin and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) reuptake (SNRI). It has negligible affinity for other neurotransmitter receptor sites and so produces less sedation and fewer antimuscarinic effects. It can be given in slow-release form with the advantage of once-daily dosage. Nausea is the commonest side-effect and patients should be monitored for hypertension. It should not be prescribed in those with either uncontrolled hypertension or in those prone to cardiac arrhythmias; if an arrhythmia is suspected, it should be ruled out by ECG before starting treatment. Duloxetine works in a similar way to venlafaxine and has been found especially helpful with chronic pain.

NSSA: mirtazapine is a 5HT2 and 5HT3 receptor antagonist and a potent α2-adrenergic blocker. The consequent effect is to increase both noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and selective serotonin transmission: an NSSA. It can be given at night to aid sleep and rarely causes sexual side-effects. Mirtazapine can be sedating in low dose and can cause weight gain. An uncommon adverse effect is agranulocytosis.

NSSA: mirtazapine is a 5HT2 and 5HT3 receptor antagonist and a potent α2-adrenergic blocker. The consequent effect is to increase both noradrenaline (norepinephrine) and selective serotonin transmission: an NSSA. It can be given at night to aid sleep and rarely causes sexual side-effects. Mirtazapine can be sedating in low dose and can cause weight gain. An uncommon adverse effect is agranulocytosis.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

These act by irreversibly inhibiting the intracellular enzymes monoamine oxidase A and B, leading to an increase of noradrenaline (norepinephrine), dopamine and 5HT in the brain (see Fig. 23.3). Because of their side-effects and restrictions while taking them, they are rarely used by non-psychiatrists. MAOIs also produce a dangerous hypertensive reaction with foods containing tyramine or dopamine and therefore a restricted diet is prescribed. Tyramine is present in cheese, pickled herrings, yeast extracts, certain red wines, and any food, such as game, that has undergone partial decomposition. Dopamine is present in broad beans. MAOIs interact with drugs such as pethidine and can also occasionally cause liver damage.

Antidepressant use in general medicine

Cardiac disease. In people with cardiac disease, SSRIs, lofepramine and trazodone are preferred over more quinidine-like compounds.

Cardiac disease. In people with cardiac disease, SSRIs, lofepramine and trazodone are preferred over more quinidine-like compounds.

Epilepsy. MAOIs and mirtazapine do not affect epileptic thresholds.

Epilepsy. MAOIs and mirtazapine do not affect epileptic thresholds.

Drug interactions. SSRIs are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, unlike venlafaxine, mirtazapine and reboxetine; the latter therefore have fewer drug interactions.

Drug interactions. SSRIs are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, unlike venlafaxine, mirtazapine and reboxetine; the latter therefore have fewer drug interactions.

Herbal medicine. Care should be taken not to prescribe antidepressants while a patient is taking the herbal antidepressant St John’s wort, which interacts with serotonergic drugs in particular.

Herbal medicine. Care should be taken not to prescribe antidepressants while a patient is taking the herbal antidepressant St John’s wort, which interacts with serotonergic drugs in particular.

Elderly. Doses of antidepressants should initially be halved in the elderly and in people with renal or hepatic failure.

Elderly. Doses of antidepressants should initially be halved in the elderly and in people with renal or hepatic failure.

Pregnancy. Antidepressants should be avoided if possible in pregnancy and breast-feeding. If other treatments are ineffective, the risks of drug therapy should be balanced against taking no treatment, since depression can affect fetal progress and future mother-child bonding. Tricyclic antidepressants are generally believed to be safe in pregnancy, with no significant increase in congenital malformations in fetuses exposed to them. However, occasionally their antimuscarinic side-effects produce jitteriness, sucking problems and hyperexcitability in the newborn. Postpartum plasma levels of babies breast-fed by treated mothers are negligible. SSRIs do not seem to be teratogenic but manufacturers advise against their use in pregnancy until more data are available. Pulmonary hypertension in the newborn is a rare complication. MAOIs should be avoided during pregnancy because of the possibility of a hypertensive reaction in the mother.

Pregnancy. Antidepressants should be avoided if possible in pregnancy and breast-feeding. If other treatments are ineffective, the risks of drug therapy should be balanced against taking no treatment, since depression can affect fetal progress and future mother-child bonding. Tricyclic antidepressants are generally believed to be safe in pregnancy, with no significant increase in congenital malformations in fetuses exposed to them. However, occasionally their antimuscarinic side-effects produce jitteriness, sucking problems and hyperexcitability in the newborn. Postpartum plasma levels of babies breast-fed by treated mothers are negligible. SSRIs do not seem to be teratogenic but manufacturers advise against their use in pregnancy until more data are available. Pulmonary hypertension in the newborn is a rare complication. MAOIs should be avoided during pregnancy because of the possibility of a hypertensive reaction in the mother.

Uncommonly used treatments

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) shows moderate efficacy, but is uncommonly used. Psychosurgery is very occasionally considered in people with severe intractable depressive illness, when all other treatments have failed (see p. 1181). A third improve remarkably, while a further third improve somewhat.

Psychological treatments

Social treatments

Many people with clinical depression have associated social problems (Box 23.8). Assistance with social problems can make a significant contribution to clinical recovery. Other social interventions include the provision of group support, social clubs, occupational therapy and referral to a social worker. Educational programmes, self-help groups, and informed and supportive family members can help improve outcome.

Mania, hypomania and bipolar disorder

Mania and hypomania almost always occur as part of a bipolar disorder. The clinical features of mania include a marked elevation of mood, characterized by euphoria, over-activity and disinhibition (Table 23.14). Hypomania is the mild form of mania. Hypomania lasts a shorter time and is less severe, with no psychotic features and less disability. Hypomania can be distinguished from normal happiness by its persistence, non-reactivity (not provoked by good news and not affected by bad news) and social disability.

| Characteristic | Clinical feature |

|---|---|

|

Mood |

Elevated or irritable |

|

Talk |

Fast, pressurized, flight of ideas |

|

Energy |

Excessive |

|

Ideas |

Grandiose, self-confident, delusions of wealth, power, influence or of religious significance, sometimes persecutory |

|

Cognition |

Disturbance of registration of memories |

|

Physical |

Insomnia, mild to moderate weight loss, increased libido |

|

Behaviour |

Disinhibition, increased sexual activity, excessive drinking or spending |

|

Hallucinations |

Fleeting auditory |

Treatment

Acute mania or hypomania

This is summarized in Table 23.15.

Acute mania is treated with an atypical antipsychotic (neuroleptic), sodium valproate or lithium. The atypical antipsychotics aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone are particularly recommended, especially with behavioural disturbance. Doses are similar to those used in schizophrenia. The behavioural excitement and overactivity are usually reduced within days, but elation, grandiosity and associated delusions often take longer to respond.

Acute mania is treated with an atypical antipsychotic (neuroleptic), sodium valproate or lithium. The atypical antipsychotics aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone are particularly recommended, especially with behavioural disturbance. Doses are similar to those used in schizophrenia. The behavioural excitement and overactivity are usually reduced within days, but elation, grandiosity and associated delusions often take longer to respond.

Lithium may be used in instances where compliance is likely to be good; however, the screening necessary prior to its use (see below) may prohibit its use in these circumstances as a first-line agent.

Lithium may be used in instances where compliance is likely to be good; however, the screening necessary prior to its use (see below) may prohibit its use in these circumstances as a first-line agent.

Valproic acid is also helpful in hypomania or in rapidly cycling illnesses (see below).

Valproic acid is also helpful in hypomania or in rapidly cycling illnesses (see below).

Table 23.15 Treatment options for the management of acute mania or hypomania

| Choice of agent is determined largely by clinical judgement, contraindications and prior response | |

|---|---|

|

Stop antidepressant medication |

|

|

If the patient is NOT on antimanic medication, then start: |

If the patient is already ON antimanic medication: |

|

Antipsychotic, e.g. aripiprazole 15 mg daily |

If taking an antipsychotic: Check dose and compliance. Increase if possible or add valproate or lithium |

|

Or Valproate 750 mg daily |

If taking valproate: Check plasma levels and increase dose aiming for a serum concentration of 125 mg/L as tolerated and/or add an antipsychotic (this should be done if mania is severe) |

|

Or Lithium 0.4 mg daily to serum lithium of 0.4–1.0 mmol/L |

If taking lithium: Check plasma levels and increase the dose to gain a level of 1.0–1.2 mmol/L if necessary (Note: higher than usual reference range) or add an antipsychotic (this should be done if mania is severe) |

|

|

If taking carbamazepine: add an antipsychotic if appropriate |

|

If response is inadequate: |

|

|

A short-acting benzodiazepine may be added to assist with agitation in all patients |

|

Prevention in bipolar disorders

Lithium

Screening prior to starting lithium and at 6-monthly intervals thereafter includes:

Thyroid function (free T4, TSH and thyroid autoantibodies). Lithium interferes with thyroid function and can produce frank hypothyroidism. The presence of thyroid autoantibodies increases the risk.

Thyroid function (free T4, TSH and thyroid autoantibodies). Lithium interferes with thyroid function and can produce frank hypothyroidism. The presence of thyroid autoantibodies increases the risk.

Parathyroid function. Serum calcium and parathyroid hormone levels higher in 10% of patients.

Parathyroid function. Serum calcium and parathyroid hormone levels higher in 10% of patients.

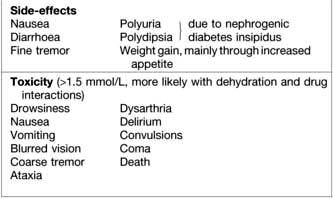

Renal function (serum urea and creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate and 24-hour urinary volume). Long-term treatment with lithium causes two renal problems: nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (DI) and reduced glomerular function (see p. 566). The best screen for DI is to ask the patient about polyuria and polydipsia.

Renal function (serum urea and creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate and 24-hour urinary volume). Long-term treatment with lithium causes two renal problems: nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (DI) and reduced glomerular function (see p. 566). The best screen for DI is to ask the patient about polyuria and polydipsia.

Toxicity. Patients should carry a lithium card with them at all times, be advised to avoid dehydration, and be warned of drug interactions, such as with NSAIDs and diuretics. As with all medications, it is vital to discuss side-effects and signs of toxicity (these are listed in Box. 23.10).

Other mood stabilizers

Both carbamazepine and valproate can be teratogenic (neural tube defects) and should be avoided in pregnancy. Other side-effects of these drugs are given in Chapter 22.

FURTHER READING

Benazzi F. Focus on bipolar disorder and mixed depression. Lancet 2007; 369:935–940.

Fountoulakis KN. Treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of available data and clinical perspectives. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2008; 11:999–1029.

McKnight RF et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 379:721–728.

The BALANCE Investigators. Lithium plus valproate combination versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar disorders (BALANCE). Lancet 2010; 375:365–375.