Chapter 4 Psychological Assessment and Intervention in Rehabilitation

Psychologists have historically played multiple vital roles in both the scientific and clinical components of the field of rehabilitation. More than 50 years ago, the specialty of rehabilitation psychology defined biopsychosocial parameters as critical parameters in the assessment and treatment of individuals with disability. This chapter is a brief explanation of the principles and practices of rehabilitation psychology. Please see the recent Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology134 for further information on these topics and for diagnosis-specific discussions.

Rehabilitation psychologists serve multiple clients including patients, family members, and staff. They also serve community entities such as schools, employers, and vocational rehabilitation agencies. This chapter provides an overview of common activities of rehabilitation psychologists and also addresses emerging topics, such as the burgeoning needs of returning military personnel and the new roles for rehabilitation psychologists.57 The reader is also directed to excellent chapters on rehabilitation psychology in the first three editions of this text, as a considerable amount of the material covered therein remains both accurate and relevant.

The most fundamental function of rehabilitation psychologists is the assessment and treatment of emotional, cognitive, and psychological disorders—whether congenital or acquired. Rehabilitation psychologists evaluate changes in neuropsychological functions that accompany brain injury or dysfunction, and advise on the implications of these for rehabilitation therapies and postdischarge life. This includes suggesting behavioral management strategies for problems such as pain and insomnia; counseling on issues related to sexuality and disability; aiding in transition from institution to community (including return to school or work)136,137; assisting in answering questions of capacity or guardianship needs; and advocating for reduction of environmental and societal barriers to independent functioning of persons with disabilities.

Rehabilitation psychologists can work with the patient and treating team and/or family groups. Although treatment teams are now found in other areas of medicine (e.g., primary care100 and psychiatry277), no other health care endeavor brings together such a diverse collection of specialists, and perhaps no other specialty has played as many unique roles on the rehabilitation team as the psychologist.55

As Diller99 wrote, “The key to rehabilitation is the interdisciplinary team.” Diller noted even back in 1990 that fiscal pressures were working to undercut the existence of interdisciplinary teams, but they have persisted. Rehabilitation teams, however, have evolved, and their composition can differ depending on the particular rehabilitation setting. As Scherer et al.330 noted, regardless of setting or area of specialization, the rehabilitation psychologist is consistently involved in interdisciplinary teamwork.

Rehabilitation psychologists can assist other staff in interpreting, understanding, and dealing with “problem behaviors” (e.g., low motivation, denial, irritability) exhibited by patients, friends, and family members.64 They can educate the treating team about the contribution of both stable personality traits and the more transient emotional responses to disability and hospitalization, to patient (and family) behavior. Rehabilitation psychologists also participate in rehabilitation research, as investigators in the Model Systems for spinal cord injury (SCI), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and burn care, for example. Rehabilitation psychologists can also use their training in group dynamics to assist in conflict resolution among team members, patient, staff, and family.62

To promote patients’ progress toward functional goals, such as resuming school and obtaining employment, rehabilitation psychologists collaborate with community agencies such as schools and vocational rehabilitation services. For example, evaluations by pediatric rehabilitation psychologists can form the basis for accommodations offered in school settings to children with congenital or acquired disabilities. Adults benefit from assessment services by rehabilitation psychologists, because these can be used to determine eligibility for services and to inform decisions regarding the nature of services that can be provided by state vocational rehabilitation agencies. Armed with knowledge of the Americans with Disabilities Act8 and related legislation, rehabilitation psychologists can be a resource for patients and community agencies regarding rights and responsibilities related to accommodations in facilities and employment settings.

Assessment

Drawing on expertise in functional neuroanatomy, psychometric theory, psychopathology, psychosocial models of illness and disability, and psychological and neuropsychological assessment and treatment applications,284 rehabilitation psychologists can provide essential assessment services in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Recognizing the multiple determinants of patient outcomes, rehabilitation psychologists take a multifactorial, multidimensional approach to assessment of cognitive functions, emotional state, behavior, personality, family dynamics, and the environment to which the patient will ultimately return.400 These assessments have many goals (Box 4-1).

BOX 4-1 Partial List of Goals of Rehabilitation Psychologists’ Assessments

Clinical Interviews and Behavioral Observations

Rehabilitation psychologists provide assessment services across the continuum of rehabilitation settings. Although the nature of the assessment varies with the referral question(s), two commonalities apply to virtually all of these assessments. First, a comprehensive clinical interview with the patient and other informants is done whenever possible. This interview covers developmental history, medical history, prior psychiatric and psychological treatment, behavioral health issues (e.g., substance abuse), educational and vocational achievements, psychosocial factors (e.g., information about family of origin, current family system, and other potential social supports), and historical style of coping with stress (see Chapter 3 in Strauss et al.353 and Part II in Frank et al.134). The focus is on the effects of psychological factors and cognitive abilities on daily functional abilities.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Overview

Neuropsychological assessment has become increasingly important in inpatient settings since the expansion of brain injury rehabilitation programs in the 1980s.84,309 Patients with brain injury or other neurologic conditions (e.g., stroke, multiple sclerosis) now comprise a large segment of the rehabilitation population, as do older adults with nonneurologic impairments who also show cognitive effects of normal aging that should be considered in rehabilitation planning.219 Inpatient screening by the rehabilitation psychologist is a standard and important component of the care of these individuals, consistent with best practices guidelines advanced by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs378 and endorsed by the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.3 Outpatient assessments of neuropsychological functioning are also critical for continuing treatment planning, making educational/vocational recommendations, and tracking outcome.336

Inpatient Neuropsychological Assessment

Early rehabilitation neuropsychology assessments can take different forms, depending on the patient’s mental status. For patients at a low level of consciousness, initial (and serial) assessment with brief screening measures (e.g., Coma/Near Coma scale,300 Orientation Log180) can identify subtle changes in cognitive functioning that are not apparent from casual observation. Such early information regarding recovery of orientation can also help predict functional outcomes at discharge.412

For individuals at Rancho Los Amigos Scale VI and above, neuropsychological testing early in acute rehabilitation provides a baseline against which changes in functioning over time can be documented. Testing during this phase also provides an early indication of patients’ potential for improvement over time. Early cognitive screening can predict later need for supervision162 and functional outcomes.98,337 It should also be noted that performance on neuropsychological testing after the resolution of posttraumatic amnesia has been associated with return to productivity (employment or attending school) at 1-year postinjury.32,73,178,320 Neuropsychological assessment results during this period more directly predict functional outcomes among individuals with TBI than does injury severity.51,271 Information from baseline testing can also be incorporated into education for family members to help them understand the sources of certain troubling behaviors (e.g., neglect, impulsivity), and to begin to envision the range of possible outcomes and start to cope with potential long-term sequelae.

Neuropsychological testing of the fully oriented patient can be a vital component of rehabilitation planning and treatment. The resulting data document cognitive strengths and weaknesses that enable the rehabilitation psychologist to suggest useful strategies for promoting learning and fostering participation in rehabilitation, and to call attention to potential barriers to progress.344 Neuropsychological assessments involve the evaluation of fundamental skills (e.g., attention, information encoding), which underlie more complex behaviors that are the goals of other therapies (e.g., learning to use adaptive equipment). Armed with a map of the patient’s “cognitive landscape,” the rehabilitation psychologist can work with the team to develop intervention strategies for maximizing the patient’s success in acquiring the skills that are the goals of therapy.

In inpatient settings, rehabilitation psychologists identify neurobehavioral problems (e.g., depression, irritability, fatigue, restlessness) that are frequently reported after brain injury.327 These difficulties can impede participation and gains in rehabilitation,294 and they also have long-term functional implications.48 Depression can result from neurologic changes,123 adjustment-related issues,317 and/or premorbid personality and psychiatric difficulties.294 Depression can significantly limit a patient’s ability to learn new skills in rehabilitation.294 Those experiencing significant depression often evidence greater functional limitations than cognitive test scores alone would predict. When such a discrepancy is uncovered, rehabilitation psychologists can highlight the interplay between psychological issues and functional performance, and assist the team in developing behavioral strategies to minimize this impediment to progress.

For individuals nearing discharge from acute rehabilitation, neuropsychological testing can inform recommendations about important postdischarge issues and complex activities such as the ability to live independently,358 to return to work or school,38 and to resume driving.229

Many patients for whom brain-related insults are not the primary admission diagnosis might also benefit from neuropsychological testing. For example, approximately half of individuals with SCI have evidence of TBI,87 a comorbidity that is seen as a particularly challenging one in rehabilitation,310 and one associated with more limited functional gains during rehabilitation224 and increased costs.39 Because their TBI-related impairments are typically more subtle than those of individuals with a primary TBI diagnosis, neuropsychological testing of individuals with SCI can be more sensitive to their cognitive impairments than are broader screening measures such as the FIM.39

Elderly patients admitted for nonneurologic problems can also benefit from inpatient neuropsychological testing. Research indicates that cognitive deficits occur with equal frequency among elderly individuals admitted for rehabilitation after lower limb fractures and those being treated for stroke.237 Neuropsychological testing of these individuals can raise awareness of subtle cognitive difficulties that might affect participation in rehabilitation. In addition, dementia appears to be more common in geriatric rehabilitation populations than in elderly individuals living in the community, but it often remains undetected in rehabilitation settings.218 Neuropsychological screening is recommended for uncovering cognitive deficits and for identifying priorities for intervention during rehabilitation and in the context of discharge planning.219 Assessment of cognitive functioning has also been shown to predict outcomes in elderly individuals admitted to rehabilitation for such conditions as hip fractures.170

Outpatient Neuropsychological Assessment

Even when assessments have been completed in the inpatient setting, outpatient neuropsychological testing is often a valuable component of follow-up care for rehabilitation populations with neurologic conditions.269 Although inpatient assessments provide valuable baseline data, numerous factors can affect recovery over time,396 and declines in cognitive functioning might even occur in a small portion of individuals. In these situations, follow-up outpatient neuropsychological testing can signal the need for further medical workup. In addition, when compared with inpatient testing results, outpatient neuropsychological assessments allow determination of changes in functioning over time. These are important data, given the observed variability in patients’ recovery patterns.257

Neuropsychological testing can be particularly valuable in deciding whether outpatient rehabilitation services are likely to be helpful for individuals who first present to physiatry clinics later in their recovery. The testing data can aid in decision making about interventions for cognitive deficits, such as the use of neuropharmacologic treatments.416 As with inpatient evaluations, the rehabilitation psychologist strives to differentiate the relative contributions of neurobehavioral, psychological, and cognitive issues to daily functioning, because this can have direct implications for treatment planning. For example, if poor daily memory functioning is due to emotional distress, psychotherapy for adjustment issues or psychopharmacologic treatment, or both, would be indicated rather than training in compensatory strategies.

Outpatient neuropsychological assessments also play an important role in educating the patient and family about ongoing cognitive and neurobehavioral consequences of the injury or insult, and promoting advocacy for the patient and family. While teaching the patient and family members about the patient’s condition is a primary goal in the inpatient setting and can have positive benefits on patient outcomes,285 families and patients rarely retain all information provided to them. A follow-up consultation after the patient has had real-life experiences of success and failure provides an opportunity for the rehabilitation psychologist to draw connections among the patient’s medical condition, neuropsychological functioning, and daily difficulties. The implications of neuropsychological test performance for daily functioning are discussed. This discussion also takes into account changes secondary to recovery of functioning and development of new compensatory strategies, as well as changes in situational factors. Assessment findings form the basis for specific recommendations regarding adaptation tactics that can be used in patients’ daily lives (e.g., memory notebooks), and for guidance regarding how to achieve or adjust as necessary long-term goals such as returning to work, school, or independent living.292

For many individuals with persistent cognitive limitations, outpatient neuropsychological testing provides a basis for addressing issues related to disability. In addition to being associated with concurrent levels of productivity,11 outpatient testing at 5 months postinjury predicts return to productivity at 1 year postinjury.158 While many individuals resume working or attending school, accommodations or assistance might be needed, and test results can help clarify just what special provisions are needed. Not only can neuropsychological testing document cognitive strengths and weaknesses for determinations of eligibility for state services (e.g., vocational rehabilitation), but it can also help guide the nature of the services that are provided. As detailed in subsequent sections, neuropsychological testing can drive recommendations regarding accommodations in the educational realm. For those individuals unable to work because of their neurologic condition, neuropsychological testing is often relied on in determinations of disability by government as well as private organizations.356

Domains Assessed

Primary domains assessed in neuropsychological evaluations include intelligence, academic ability, memory, attention, processing speed, language, visual-spatial skills, executive abilities, sensory-motor functions, behavioral functions, and emotional status.217 Box 4-2 shows selected neuropsychological measures grouped by primary cognitive domain. (Virtually all neuropsychological tests are multifactorial, so the groupings in Box 4-2 are based on the presumed major cognitive skill required by the test.) While a deficit in any area can have a significant impact on functional outcomes for a given patient, large-scale studies suggest that memory, attention, and executive functioning have particular relevance for rehabilitation populations, including individuals with TBI.151

BOX 4-2 Sample Neuropsychological Tests by Primary Cognitive Domain

Intellectual Functioning/Academic Abilities

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales (WAIS-III/WAIS-IV)386,390

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI)387

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale364

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition316

Shipley Institute of Living Scale, Revised411

Learning and Memory

Auditory Consonant Trigram Test260,287

Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test331

California Verbal Learning Test–Second Edition91

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised44

Benton Visual Retention Test24

Language Skills

Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination, Third Edition150

Multilingual Aphasia Examination25

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Third Edition108

Visual-Spatial Skills

Judgment of Line Orientation26

Hooper Visual Organization Test176

Executive Functions

Raven’s Progressive Matrices301

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test154

Memory impairments are prevalent after acquired neurologic injuries such as TBI244 and stroke,12 and can be significantly disruptive to the rehabilitation process. Memory problems can interfere with a patients’ ability to learn and retain new skills and/or develop compensatory strategies taught by rehabilitation providers. Memory problems can significantly hamper the achievement of important functional outcomes and productivity.32,156

Attention is a multifaceted construct that underlies all other cognitive skills and is especially important for intact memory functioning, because information that is not attended to cannot be recalled at a later time. Components of attention include focused attention, sustained attention, selective attention, alternating attention, and divided attention.344 In addition to memory problems, attention deficits are among the most commonly reported difficulties in persons with TBI208 and in those with a history of stroke.215 Deficits in attention are also associated with relatively poorer long-term functional outcomes, including diminished likelihood of returning to work and independent living.47

Executive functioning is a complex cognitive domain encompassing multiple skills that pervade all aspects of daily life. Neural systems engaged in executive functioning involve interconnections of diverse neuroanatomic regions,139 but the frontal lobes are viewed as especially vital. Executive functioning deficits include difficulties with problem solving, reasoning, planning, response inhibition, judgment, and use of feedback to modify one’s performance, as well as behavioral deficits such as problems with self-awareness and poor motivation. Neuropsychological tests typically focus on evaluating cognitive manifestations of executive dysfunction. Behavioral evaluation of executive functioning relies to a great extent on observations in natural settings, but some behaviors might emerge during testing. Several questionnaires are specifically designed to detect these behavioral issues, such as the Frontal Systems Behavior Sale (FrSBe).152 Deficits in executive functioning predict important outcomes such as poor quality of life174 and functional outcomes.215

Test Considerations

Fixed Versus Flexible Batteries

Rehabilitation psychologists must balance the relative costs and benefits of fixed versus flexible assessment batteries in neuropsychological assessments. With fixed batteries, such as the expanded Halstead-Reitan battery,166 the same set of tests is administered to all patients, regardless of the referral questions, and the normative data for all tests are based on a single population. Because all tests are co-normed, proponents of this approach assert that this allows for more confidence in drawing conclusions about an individual’s strengths and weaknesses, based on variability in performances across tests. Because a wide range of domains is evaluated, the rehabilitation psychologist might also identify strengths and weaknesses that were not anticipated on the basis of the referral questions or other information such as lesion locus.191

Another variant of the fixed testing approach involves the use of a test battery that is population specific15 and is developed by the rehabilitation psychologist for use with a particular patient cohort (e.g., individuals with a particular diagnosis such as multiple sclerosis).23 With this type of fixed battery, rehabilitation psychologists can amass their own clinically based normative data sets against which new patients can be compared. This approach also promotes research opportunities, because psychological and neuropsychological factors that influence participation in rehabilitation and outcomes after discharge can be identified and evaluated.

As a result, the generally preferred alternative is a flexible testing approach, one in which a core set of measures is supplemented with additional tests that are selected depending on the referral question.255 As the evaluation unfolds, measures can be added or subtracted according to early findings, as strengths and weaknesses become apparent. The examiner might elect to probe certain areas in more detail to clarify their therapeutic import. At the core of this approach is the notion that flexible batteries allow for personalization of an assessment based on patient needs.15 Flexible batteries seem more responsive to the constraints of inpatient rehabilitation settings and are the preferred approach of most neuropsychologists, regardless of work setting.297

Modifying Tests for Special Populations

In rehabilitation settings, perhaps more than in any other, psychologists must be aware of factors that can produce “construct-irrelevant variance”252 in the assessment of persons with disabilities. These influences can cause spurious elevations or depressions in test scores and result in misleading inferences about the patient’s abilities and deficits. Given that most neuropsychological measures were developed for assessment of physically healthy people, the norms might not apply to those with certain disabilities. Scores on most neuropsychological tests can also be skewed by such influences as pain, fatigue, visual difficulties, and motor impairments, problems that are quite common among rehabilitation populations. These effects should be eliminated, or at least minimized, so as not to obscure assessment of the neuropsychological phenomena of interest.

A related sort of distortion can occur with instruments intended to assess personality or emotional status, because phenomena that constitute “symptoms” for nondisabled individuals might not carry the same (or any) psychologically relevant diagnostic meaning for those having disabilities. For example, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2 (MMPI-2) contains items dealing with bowel function, sensory changes, and other physical phenomena that are typical consequences of SCI. Persons with SCI (or TBI, stroke, or multiple sclerosis, among others) who answer these questions honestly can produce profiles suggesting psychological pathology where there is none.140,253,359 Related measures such as the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) are subject to similar skewing.401

Although standardized testing is the foundation on which contemporary psychological assessment is built, there is considerable support in statements of professional organizations, test publishers, and experienced clinicians for “reasonable accommodations” in testing persons with disabilities.65 The elderly, who are a rapidly expanding segment of the population, can also require special adaptations in assessment.66 For example, the most recent edition of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-N)390 addresses these issues in a section on “suitability and fairness.” The “fairness” issue in particular is a long overdue concept in psychology.128,144 While devoting most attention to modifications for persons with hearing impairment, the WAIS-IV manual warns evaluators against “attribut(ing) low performance on a cognitive test to low intellectual ability when, in fact, it may be related to physical, language, or sensory difficulties.”390 Alterations or accommodations in the testing procedures should be recorded and taken into account in interpreting the test data. While it is recognized that “some modifications invalidate the use of norms, such testing of limits often provides very valuable qualitative and quantitative information.”390

What else can the psychologist do in such situations to ensure fair, accurate, and informative assessment? One method involves “pruning” of those items on measures designed to assess personality or emotional state that are perceived to be irrelevant to the constructs being assessed. Gass141 identified 14 potentially confounding items that, once the presence of brain injury has been established, can be removed and the protocol rescored to yield a “purified” profile. Gass140 also identified 21 “stroke symptoms” that can be handled in the same manner. Woessner and Caplan401,402 used expert consensus to determine that 14 and 19 items, respectively, from the SCL-90-R concerned phenomena that were part of the “natural history” of TBI or stroke. They argued that scores indicating pathology in physically healthy people could hold very different diagnostic significance for persons with acute or chronic medical conditions. Failure to attend to possible scale distortions could lead to misinterpretation, erroneous diagnosis, and subsequent misguided treatment.

Some authors49,106 have argued against this method, maintaining that important information might be lost if items are deleted from standard measures, or that the psychometric properties of the instrument could be significantly altered. These authors based their position on studies of individuals in litigation, however, where validity is a pervasive concern. Stein et al.351 offer a nuanced discussion of the pros and cons of retaining or eliminating “somatic items” in assessment of stroke survivors, pointing out that while these might represent a clinical problem, their mere presence offers no clue to etiology and, therefore, to treatment. The rehabilitation psychologist must analyze these symptoms in light of all available information to determine whether a psychologically treatable problem exists.

In the case of neuropsychological measures, greater ingenuity (and caution) is required to ensure that valid information is obtained from test administration. Although one naturally wants to know the impact of the disabling condition on the individual’s functioning, one does not want to consume time and energy simply to confirm the obvious. It is poor practice to administer a 60-item test of visual processing only to discover that the patient saw only part of the stimulus display because of a neurologically based deficit in attention to and awareness of one side of space (unilateral neglect). Possible strategies range from simply allowing extra time for those with psychomotor slowing or impaired manual dexterity, to actually modifying test materials themselves. Berninger et al.28 adapted certain subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised for use with persons with speech or motor disabilities. They created multiple-choice alternatives for verbal measures (allowing participants to point to their chosen answer), enlarged visual stimuli, and used materials adapted with Velcro to reduce the impact of motor impairment when manual manipulation is required. Caplan60 created a “midline” version of the Raven Coloured Progressive Matrices, a multiple-choice, “fill-in-the-blank” test of visual analysis and reasoning. Response alternatives are arrayed in a single column instead of rows, eliminating the lateral scanning component that limits the performance of patients with unilateral neglect. Patients with neglect performed significantly better on “midline” items than the standard ones, while those without neglect performed equally well on both types of item.

Not all authors support this approach. Lee et al.214 cautioned that even minor deviations from standard procedures can produce “significant alterations” in performance. We view this as part of the challenge in practicing what is still the “art” of assessment, an endeavor with a substantial scientific base but one that does not mandate robotic behavior on the part of the examiner.

Test Interpretation

Population normative data provide a benchmark for the average level of ability on a certain task for a given population. Some data sets include corrections for factors that can affect test performance, such as gender, age, and education.166,220 The Heaton et al.166 database designates particular T-score ranges as “above average” (T = 55+), “average” (T = 45 to 54), or “below average” (T = 40 to 44), and these encompass roughly 85% of all scores. “Impaired” scores of increasing severity (e.g., “mild” or “moderate to severe”) are associated with progressively lower T-score ranges of 5 points, with the exception of “severe impairment” (T = 0 to 19). Increasing attention is also being paid to the influence of cultural factors,124,126 although the development of truly “culture-free” or “culture-fair” neuropsychological assessment tools is in its infancy. Although understanding an individual’s functioning compared with population norms can be a helpful starting point, it is also necessary to determine whether a decline from the “average level” reflects a loss of functioning for a particular individual. This requires a consideration of a patient’s likely premorbid abilities.

In the absence of premorbid neuropsychological data (i.e., from testing before insult), estimates of premorbid functioning allow for intraindividual comparisons by identifying a probable baseline against which current test scores can be compared. Techniques for inferring premorbid abilities include the following:

An understudied problem is the variability with which certain terms are used in describing test performance. While adherence to a system such as that of Heaton et al.166 described above ensures consistency in the use of “impairment descriptors,” the process of drawing intraindividual comparisons by using premorbid estimates can lead to meaningful differences across clinicians in the application of such terms as “moderately impaired,” “within expectation,” or “within normal limits.” One can argue that mixing within a single report of “normative descriptors” (e.g., “high average,” “borderline”), “impairment descriptors” (e.g., “mildly impaired,” “defective”), and “expectation descriptors” (e.g., “within expectation,” “below expectation”) is both semantically inconsistent and conceptually confusing.61,159 A “high average” score for an exceptionally well-educated individual might still reflect “mild impairment,” while a “borderline” score could still be “within expectation” for one with far less schooling. Clear communication between the rehabilitation psychologist and the consumers of neuropsychological assessments (e.g., patient, family members, physiatrists, and other health care providers) is required to ensure that test findings are explained in a manner that clarifies the conclusions regarding an individual patient’s relative strengths and deficits.

Factors Affecting Validity

Interpretation of serial neuropsychological assessments, conducted to monitor functioning over time or determine the efficacy of interventions, can be clouded by practice effects—that is, improvements in test scores resulting from familiarity with the test (or even with the process of testing) rather than real gains in cognitive functioning. Research has indicated that some tests are more susceptible to practice effects, such as those evaluating memory.242 Rehabilitation psychologists take several steps to minimize the impact of practice effects. First, comprehensive retesting evaluations are generally scheduled at sufficiently lengthy intervals (e.g., at least 6 months) to reduce the likelihood that patients can remember the test content. Alternative test forms with different test stimuli can also be used. This is especially important when the retest interval is brief. For example, comparable sets of words can be used for list-learning tasks (e.g., Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised).44 There is also growing documentation of the utility of statistical corrections, such as the Reliable Change Index181 and regression-based models360 to determine whether genuine and clinically relevant change has occurred on repeat testing.167

Although the importance of assessment of patient effort has been recognized for some time,282 there has been an avalanche of reports on “symptom validity” testing during the past decade, in large part because of the increased use of neuropsychological findings in forensic settings.37,212 Although poor patient effort has been estimated to occur in 15% to 30% of forensic evaluations, the likely frequency in clinical settings remains relatively low at 8%.260,313 Current standards of practice propose that assessment of symptom validity is a necessary part of all evaluations, although the procedures can vary in different settings.51 Several aspects of patients’ presentations can be examined for indications of poor or variable effort, including variability of performances across tests measuring similar abilities, and consistency between presenting medical factors (e.g., lesion locus) and test performance. One can ask whether the data exhibit “neuropsychological coherence.” Indices of effort are embedded in some tests that are often standard components of neuropsychological evaluations.254 Measures that rely on normative comparisons or use a forced choice paradigm have also been specifically developed as tests of “motivational impairment.”29,37,212

Psychological Assessment

Psychological Issues in Rehabilitation Settings

Depression and Anxiety

Depression and anxiety are commonly seen in rehabilitation and medical settings134 in degrees that exceed “normal” reactions to loss. Depression and anxiety are both painful and problematic, and they require identification and treatment. Estimates of the prevalence of these disorders vary widely because of differences in measurement tools and diagnostic criteria. Studies suggest that 10% to 60% of persons experience depression and 5% to 30% experience anxiety after a stroke.68,349 After an SCI, depression is observed in 11% to 40% and anxiety in 25% to 60% of patients.34,113,114,138,197 As many as one third of persons who have undergone lower limb amputations experience depression.323 Persons with TBI experience a range of psychiatric symptoms, with 30% to 80% having depression, anxiety, or behavioral problems.119,188 While further research is needed to understand why the estimates vary so greatly (and to refine our diagnostic criteria), the existing data confirm that depression and anxiety are prevalent in rehabilitation settings.

Personality Disorders and Personality Styles

Personality disorders are persistent patterns of behavior that produce impairment in occupational or social functioning. Persons with certain personality disorders can experience higher rates of injury through suicide attempts, assaults, and other violent incidents. Persons with preinjury obsessive-compulsive and antisocial personality disorders might be overrepresented among persons who experience TBI.171

Some maladaptive personality styles and traits, while not causing impairment in social or vocational functioning, might be disproportionately represented in certain rehabilitation groups. Persons with extroverted, risk-taking styles might become involved in accidents resulting in SCIs.314 Clinical interventions need to take these personality styles into consideration. For example, “action-oriented, risk-taking” individuals might learn better by doing than by discussing (perhaps an advantage in physical therapy), and might receive and accept advice better from their peers than from their doctors.314

Substance Abuse

Substance misuse is dramatically overrepresented among persons with traumatic injuries such as TBI and SCI.36 At the time of injury, one third to half of persons with TBI were found to be intoxicated.82 Marijuana (24%), cocaine (13%), and amphetamines (9%) are also often detected.35 Among persons who sustained SCIs, 29% to 40% were intoxicated at the time of the injury.168,216

Denial of Illness

Denial is commonly seen in rehabilitation settings,205 but denial is not a unitary phenomenon (see Caplan and Shechter63 for a discussion of various typologies). The word “denial” can describe a neurologically based symptom or a psychological coping process. In extreme cases, persons might deny the existence of the condition or, while acknowledging the condition, might deny or minimize the implications that it will have for their lives.

Psychological denial as a coping mechanism is commonly seen after a sudden and identity-threatening loss. Denial entered public awareness when Kübler-Ross210 described her work with terminal cancer patients. Over time, the stage theory of adjustment that she proposed, of which denial was one phase, has not been substantiated.113,133 The concept that denial, anger, and other emotional reactions are normal parts of the adjustment process, however, created a climate in which these reactions could more easily be discussed.

Deficit denial, also known as anosognosia, is a pernicious, neurologically based kind of denial that presents significant barriers to rehabilitation.295 Affected individuals might not want to engage in therapies or use compensatory strategies to alleviate deficits that they do not believe they have. Challenges are also faced by family members who try to set limits to protect patients from harm and, in doing so, can be perceived by patients as controlling or overly anxious. In some instances, this symptom can be chronic and sabotage rehabilitation. A détente might be sought, however, in which the patient agrees to humor family and professionals by “going along with” the story that he or she has a deficit. Additional interventions are discussed below.

Measurement of Psychological Status

In inpatient settings, assessment of emotional state is typically accomplished through a clinical interview and perhaps brief inventories. Fatigue, pain, cognitive problems, and medications can all affect patients’ ability to participate in testing and the validity of the results.185 Current symptoms and behaviors are evaluated in a clinical interview, with consideration of the patient’s psychological and behavioral health history, psychosocial functioning, recent medical event, and medications. Short questionnaires can also be used. Questionnaires with a “yes-no” format are preferable for persons who have cognitive impairment. Interpretation of the findings relies significantly on clinical judgment, because the overlap between psychological and medical symptoms, as well as lifestyle changes inadvertently imposed by the medical event, can be mistakenly interpreted as signs of psychological distress. Serial assessments can help factor out acute influences that might affect diagnostic impressions. Some commonly administered measures of emotional status are listed in Box 4-3.

BOX 4-3 Measures of Emotional Status

In outpatient settings, patients might be more capable of completing lengthier measures assessing personality factors that affect response to treatment. Obtaining such measures is particularly important in cases involving litigation because the data can help clarify the effect of psychological factors on the patient’s symptom presentation. Several measures have been specifically developed for use in populations having medical disorders. These include the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory–III (Millon),259 which measures emotional as well as personality disorders, and the Millon Behavioral Medicine Diagnostic (MBMD).258 The MBMD provides information about health habits, coping styles, psychiatric conditions, stress moderators, and factors that can affect patients’ response to medical interventions. For assessment of general personality and psychopathology, the MMPI-253 and the Personality Assessment Inventory264 are widely used. Because these two inventories have not been validated on rehabilitation populations, the applicability of standard norms is unclear. As noted earlier, profiles from certain rehabilitation populations might inaccurately suggest psychopathology.

Assessment of chemical use history is important in rehabilitation settings, given the high incidence of substance abuse in persons who have sustained traumatic injuries and the destructive impact continued misuse can have on persons with disabilities.36 Brief screening questionnaires such as the CAGE (four items),118 the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C; three items), and variations of the Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) (e.g., Short MAST334) are valid for identifying alcohol use problems in medical settings.40,273 These tests are in the public domain and can be easily incorporated into health screening (Box 4-4). Some efforts have been made to validate these measures with special groups, such as geriatric populations.273 Rapid screening tests for abuse of other substances have not yet been validated with medical populations, although research points to the potential utility of a modified MAST (MAST/Alcohol-Drug393). Consequently the identification of drug abuse might require interviews with the patient and family, with an awareness that they might be reluctant to acknowledge abuse, given the potential legal implications.

BOX 4-4 Alcoholism Screening Questionnaires

Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (SMAST)334

CAGE118

Emotional/Psychological Variables and Rehabilitation Outcomes

A growing body of evidence supports the need to address psychological issues as part of the entire rehabilitation plan. Depression has been linked to higher mortality,187 slowed rehabilitation progress, less favorable functional outcome, and poorer psychosocial recovery.317,377 Anxiety can result in avoidance behaviors—that is, “being unavailable” for therapy. Persons experiencing life-threatening events are also at risk for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This disorder has been observed in 3% to 27% of persons after TBI173 and 7% to 17% of those with SCI.270,298 Preinjury alcohol abuse predicts poorer outcome in individuals sustaining traumatic injuries. It is associated with the development of emotional problems, difficulty integrating into vocational and social activities, a higher risk for reinjury,82,189 and the development of pressure ulcers.115 These findings show the importance of psychological assessment and subsequent psychological interventions in improving patients’ outcomes.

Intervention

Rehabilitation psychology interventions are framed within a biopsychosocial-environmental perspective and (with the exception of cognitive rehabilitation) use a coping model. This framework acknowledges that individuals’ experiences are shaped by their bodies, minds, relationships, and environments. It is a health-based model that harnesses and augments patients’ existing capacities to deal with the challenges they face. Informed by assessment findings and input from the rehabilitation team, psychologists foster a combination of realism, hope, and motivation; help the patient and family digest and accommodate to their changed circumstances; and facilitate reconnections to social and vocational roles. The goal is an adjustment process that leads patients and families to find meaning and satisfaction in their “new normal” lives.322

Foci of Psychological Interventions

Psychologists face particular challenges in rehabilitation settings, working with patients who might hold biases against psychology. Patients might be unaware of their problems or see them as merely temporary. They are typically unaware that their impairments and disabilities initiate a cascade of events that can significantly affect their relationships and social roles. A complex interplay of medical, psychological, social, legal, and environmental factors affects a person’s functioning and well-being, and a perspective that addresses only the psychosocial issues is inadequate.275,276 Interventions must be planned with the goal of enhancing functioning. Consequently it is important to consider how the person’s physical and psychosocial environment might facilitate or impede functioning, and to address as many of these factors as possible.

Inpatient Rehabilitation

Soon after a loss, patients and families are faced with a mixture of emotions. Seemingly contradictory feelings can coexist, and patients (and family members) can cycle rapidly from one to another. Many experience two sets of emotions: a reaction to the disabling event and a reaction to their perceived future. Sadness, anxiety, and relief at having survived coexist with determination and the hope (and expectation) that recovery to their preinjury state is possible. The pertinent psychological issues at this phase are maintenance of hope (without being deceptive); identifying, engaging, and supporting use of effective coping strategies; grappling with and planning for changed life circumstances; managing behavioral problems; and preventing and treating depression and anxiety. It is important to recognize that in the early phase, patients’ denial of long-term implications of their condition might help maintain hope and motivation for arduous therapies,205 and might be an efficient way to manage prognostic uncertainty. There is usually little to be gained by stark confrontation of “verbal denial” at this point, especially if the patient is not exhibiting “behavioral denial” by refusing treatment.

Contemporary inpatient rehabilitation emphasizes improving patients’ functional capacities to the point at which their physical needs can reasonably be met by family or other caregivers in a home setting. Current lengths of stay seem astonishingly short compared with those of even two decades ago. This brevity requires all team members to be focused in their goals, efficient in their activities, timely in communications, and adept at building confidence as well as skills in patients and families. In working with the inpatient rehabilitation team, the rehabilitation psychologist faces several tasks concerning emotional and behavioral domains (Box 4-5).

BOX 4-5 Rehabilitation Psychologist’s Tasks in Regard to Emotional and Behavioral Domains

Facilitating Awareness and Acceptance of Change

Clarifying the patient’s understanding of the physical and cognitive changes that have occurred and their implications for daily functioning can open a window into the patient’s internal world. Understanding the patient’s beliefs, expectations, and experiences (the “insider perspective”91) helps the psychologist and team make sense of the patient’s reactions and aids in selecting interventions that will “ring true” for the patient. Learning the patient’s emotional history, including characteristic coping styles and strengths, can yield insight into the patient’s likely emotional course in rehabilitation. It should be noted that the extent of distress experienced after an illness or injury is frequently better explained by coping capabilities than by the injury itself.85 If there is a history of alcohol and drug misuse, targeted education and intervention might be needed, because substance abuse impedes rehabilitation recovery and restricts long-term outcome.36

The psychological status of patients in inpatient settings evolves, often (but not always) in concert with their physical and medical conditions. Like the rest of the team, the psychologist must work swiftly, serially assessing the patient’s psychological condition, digesting this information, advising the team regarding the most effective ways to communicate with the patient, and working with the patient and family members to conceptualize the disability as a challenge to be handled rather than being an unmanageable, devastating event. In the inpatient phase, patients often begin building connections between their epistemologic systems and the occurrence of the event. The frequent question “Why me?” is the beginning of the process of finding meaning in the event.88 Although expressions of anger toward “God” have been associated with poorer emotional adjustment283 and functional outcomes,125 some patients express acceptance based on a perception that their condition is an expression of “God’s will.” Those in whom this notion leads to passivity can be reminded, however, that “the Lord helps those who help themselves.”

Addressing Social and Environmental Factors

The patient’s “family” is an important target of intervention for inpatient rehabilitation. Like the patient, the family is also struggling to make sense of dramatically changed circumstances affecting family structure and processes.280 Family roles can shift, as others take over functions formerly fulfilled by the patient. Usually it is not known for some time whether these role shifts are temporary or permanent. Family pathology can surface when problems with communication, emotional support, and practical problem solving interfere with the family’s adaptation. Intervention is essential because the quality of family interactions with the patient makes a measurable difference in patient outcome. Stroke patients with families that are emotionally supportive and provide necessary practical help make better emotional and physical recoveries, regardless of the stroke severity285; this finding may apply to persons with other causes of disability as well.280

“Nontraditional” couples and families might face special challenges in medical rehabilitation. Research is largely lacking on specific challenges of persons with disabilities who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgendered (GLBT),81 and in regard to their sexual experiences and sexual expression.132 Rehabilitation professionals know little about the specific psychosocial challenges of persons who are GLBT (e.g., homophobia, use of specific recreational drugs, spiritual issues, and sexuality),172 and these issues are unlikely to be adequately addressed in medical rehabilitation programs. In the past, state laws added additional barriers, and therapists often found themselves choosing between adherence to state laws regarding sexual practices (e.g., prohibiting sodomy) and serving the needs of GLBT patients with disabilities.13 Patients who are in gay or lesbian relationships who have not “come out” can find it difficult to get support from their partners without compromising the privacy that they have protected. Partners also face new challenges, including those related to proxy decision making.

Crisis Intervention

“Normal” Crises

A psychoeducational model involves describing possibilities for patients and families without directly challenging their experience and beliefs. This approach has the potential to invite change while raising little resistance. Kreutzer and Taylor207 have developed a manualized program for patients and families after TBI. In this program a brain injury is presented as a problem that can be managed like any other. Patients and families help define the changes that have occurred from the brain injury, and then are encouraged and helped to find ways to address them. This model provides definition and boundaries to the impact of the injury, encourages people to recognize continuities in their lives, and suggests that satisfying experiences can still occur. For persons with stroke and their families, a one-session psychoeducational intervention discussing coping, burnout, social and recreational activities, and other practical ways to manage stress has been developed, and the initial research has shown it to be effective.281

Behavioral and Extraordinary Crises

Extreme crises also occur in rehabilitation practice. Patients and families can face decisions about terminating ventilators, dialysis, or other extraordinary care, resulting in the patient’s death.56 These situations typically spawn intense emotion in rehabilitation team members, who are torn by their own ethics, morals, and quality-of-life assessments. Team members often covertly vote on whether the patient and family are making the right decision, which can produce disruption in the team and send mixed messages to patients and families. In these situations, psychologists can identify and illuminate the factors pertinent to the decision and support the patient and family in their decision-making process, while simultaneously unifying the team and helping the team deal with its grief.

Preparing for Discharge

At the time of discharge, patients with TBI might still exhibit impaired self-awareness,294,296 and they might still be denying the duration of the change, its significance, or both. Intervention is needed if diminished awareness of one’s limitations jeopardizes safety or implementation of rehabilitation recommendations.

When considering the need for intervention, it is important to distinguish between verbal and behavioral denial. If patients act as if they have experienced a disabling event (e.g., participate in therapies, follow recommendations for assistance), it matters little how they describe their conditions. When denial carries over into their actions, however, refusing therapies (saying that nothing is wrong with them or that the problem will go away), this “behavioral denial” becomes problematic. In such cases, providing objective, structured feedback or having patients participate in ecologically valid tasks that elicit their deficits might increase self-awareness.70

Rehabilitation psychologists work with patients and family members as they cope with the ambivalence that can be triggered by discharge from the inpatient setting. Eager though they might be able to go home, the fact they are preparing for discharge with a disability communicates that their functional changes will not quickly resolve. It is often productive to encourage a focus on the near future, with the message that plans and decisions must be made on the basis of current functioning. Further recovery can be hoped for but not counted on. In this way the psychologist teaches the important distinction between “hope” and “expectation.”63 Apprehension regarding discharge is also eased by a reminder that improvement does not necessarily terminate when one leaves the hospital. Patients can be reassured that there comes a point when outpatient therapy or a home program can be as productive as inpatient treatment, and the psychological benefits of being in one’s familiar surroundings cannot be minimized.

Outpatient Rehabilitation

In leaving the inpatient setting, patients must be prepared for reentry into both their physical and psychosocial environments. The home that was previously so comfortable might now present multiple obstacles. Navigating “familiar” places (grocery stores, churches, etc.) is a new and often unpleasant experience, evoking frustration, anger, or avoidance. The psychosocial environmental reentry is no less challenging. People often ignore those with disabilities in an attempt to deal with their own anxiety.170 Others might react primarily to the disability,410 overgeneralizing its significance. Waiters might ask accompanying family members what “he” (i.e., the person in the wheelchair) would like to order. Children will learn to capitalize on their mother’s memory impairment or might hesitate to bring friends home, fearing unpredictable behavior from their brain-injured father.

Managing a disability and maintaining one’s place in society requires assertiveness, because passivity can lead to exclusion and isolation. Learning that it is all right—indeed necessary—to advocate for oneself from simple tasks (e.g., requesting assistance to reach groceries, explaining the need for accommodations when booking a hotel room) to the more complex (e.g., arranging for workplace accommodations, communicating one’s preferences in a sexual relationship).108 Personality styles tend to be consistent across the adult life span,78 and premorbidly shy persons with a disability might find it difficult to adjust their style of relating in society. However, assertiveness is a skill that can be learned.110

Psychosocial issues become increasingly prominent in the outpatient setting. As medical conditions stabilize, the physical and cognitive recovery curve flattens, and physical interventions diminish. The person takes on an increasingly challenging task of learning how to reenter, with changed abilities, the life they had built. In this context the rehabilitation psychologist deals with a mix of emotional, social, and existential issues. Over time, as denial diminishes, the patient’s increased awareness of change and loss can trigger bereavement, depression, anxiety, overcompensation, or other emotional or behavioral reactions. Cognitive changes might further complicate the process. Persons with disabilities must deal with resuming or retiring from family and occupational responsibilities. In most cases, income has shrunk, expenses have risen, and the amount of work to be done in a day (including processing paperwork related to insurance claims, Social Security Disability applications, attending therapies and doctors’ appointments) increases. It is a stressful time in which resources are strained, the patient and family are fatigued, and uncertainty is high. Patients and families often vacillate between hoping that their lives will return to normal and fearing that they will need to adapt to a “new normal.”

Addressing Family and Caregiver Issues

Family structure and family roles (e.g., communication, emotional support, problem solving) are disrupted by disabling events.280 Caregivers can be at particular risk for distress, especially those caring for persons having problems with memory and comprehension that often follow brain injury or stroke.58 There is evidence, however, that caregiver resentment is diminished when problem behaviors are attributed to the illness rather than the person,395 as when the cause is seen as the “brain injury,” not the “difficult husband.” Factors such as family role, access to social support, and caregiver social problem-solving skills all modulate the emotional impact of caregiving.155

Patients’ recoveries are affected, in turn, by their families’ behaviors. For example, one study of stroke patients showed better functional and emotional recovery among patients whose families were emotionally supportive and provided appropriate levels of practical assistance.280

Scope of Care

Rehabilitation psychologists in outpatient practice are often called on to identify and treat a range of psychological issues. Cases that might initially be conceptualized as “adjustment disorders” (anxiety or depression after a loss) might over time become highly complex because of prior experiences and/or preexisting factors such as child sexual abuse,228 borderline personality disorder,153 antisocial or obsessive-compulsive personality disorders,171 and substance abuse. As noted above, PTSD related to the injury is not uncommon after TBI173 or SCI.270,298 A brain injury might also precipitate reemergence of previously resolved PTSD symptoms.302

Just as many former rehabilitation patients require lifetime medical monitoring, their chronic cognitive, psychosocial, vocational, and behavioral problems can merit psychological consultation, intervention, or both, at any point after discharge. For example, persons with TBI can have chronic cognitive problems,104 especially with processing speed, memory, and executive functioning. These cognitive deficits, coupled with difficulties adjusting to postinjury life, can cause lowered self-confidence, relationship failures, and problems managing negative affect.171 These individuals might benefit from rehabilitation psychology consultation as they grapple with changed psychosocial circumstances. Persons with other disabling conditions might also benefit from seeking consultation with psychologists as they encounter new life challenges.385

Intervention Modalities

Therapeutic intervention is a complex interchange between therapist and patient, in which the therapist simultaneously monitors and manages rapport, communication style, comprehension of material, and emotional tone. A particular clinical problem can manifest itself in the patient’s behaviors, thoughts, emotions, relationships, and social roles. A wide range of issues might need to be targeted by clinical treatment plans as a result.321 Although psychologists use theoretic approaches to structure their observations and guide their decision making, the selection of a specific intervention is based on the nature of the problems, the characteristics of the patient, and the training of the psychologist, as well as to some degree the psychologist’s personality. The immense variety of medical conditions, neurobehavioral disorders, social and familial circumstances, and other factors encountered in rehabilitation populations mandates a highly individualized and eclectic approach.

General Principles of Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is a method for assisting clients to understand their emotional and behavioral reactions, and create the potential to act from a position of choice, rather than from reflexive responding. The various types of interventions are useful for structuring the psychotherapist’s thinking, observations, and choice of how to respond. The intervention helps the psychotherapist organize a complex set of data in patterns, so that the therapist will know how to understand the material that the client is bringing, and how to formulate a response to move towards the treatment goals. The form of therapy is selected according to the clinical question and, whenever possible, the preferences of the patient. Psychologists also remain mindful that a key “active ingredient” in psychotherapy is the therapeutic alliance235; therapists who are perceived as likable, compassionate, and empathic tend to achieve good outcomes.

Like all areas of health care, psychology is moving toward data-driven treatments. Rehabilitation psychology faces several challenges in doing so: (1) measuring the relationship, (2) measuring the intervention, and (3) translating research to clinical practice. Measuring the relationship is critical, given that a consistently potent factor in psychotherapy is the alliance that exists between the patient and the therapist.235 As this is an interactional variable (i.e., it involves both the therapist and the patient), it is impossible to predict in advance whether a particular therapist will have a good working relationship with a particular patient. We also do not have tools to measure whether a “good-enough” working relationship exists between patient A and therapist B, nor do we know whether incremental benefit accrues from an “excellent” relationship as compared with a “good” relationship. With regards to measuring the intervention, some interventions (e.g., behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatments) suit themselves to manualized treatments, while others (e.g., existential) are much more fluid and harder to operationalize. Rehabilitation interventions might also need to be modified to suit the capacities and characteristics of the patients, and can depart from the form used in establishing efficacy. The final challenge is in translating research to clinical practice. Persons who have disabilities face a wider range of psychosocial issues, identity issues, and psychosocial challenges than the average person participating in a psychotherapy efficacy study, raising questions about the applicability of findings from these clinical trials to rehabilitation populations.357,366

Interventions Targeting Behaviors and Thoughts

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation is the provision of information to assist patients in understanding and managing their condition. It promotes coping by enhancing the patient’s knowledge and facilitating informed choices. By facilitating behavioral activation and self-efficacy, psychoeducation might also provide some inoculation against depression. Psychoeducation is often offered to individuals and their families in both inpatient and outpatient settings. This intervention can often also be delivered in a group format. Psychoeducation groups are not only efficient, but they also facilitate peer support. This support can potentially penetrate the sense of isolation that often accompanies a disabling event. It can also foster “social comparison,” which can enhance coping. Participants in groups can find the comments of others to be powerful because they have shared experiences, and might perceive other patients’ observations as more credible than those made by staff.10

Skills Training

Persons with disabilities face challenges in social relationships simply by the fact of having a disability,105 and poor social problem-solving skills can even put them at higher risk for complications such as pressure ulcers (if, for example, an unassertive individual hesitates to ask for assistance with weight shifts).112 Skills training involves demonstrating and practicing behaviors required for specific circumstances, and includes assertiveness training, role-playing, and relaxation training.148 While skills training often occurs in the context of individual therapy, group therapy can be an efficient way to teach and practice basic emotional management skills, such as relaxation procedures and cognitive methods to reduce distress. Members can learn from each other and benefit from healthy competition. Group therapy, however, is typically not suited to dealing with idiosyncratic or highly private issues.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing256 is a therapeutic technique designed to facilitate a person’s movement through ambivalence to therapeutic change. In motivational interviewing the psychologist guides the patient in identifying advantages and disadvantages of behavior change and uses this information to guide and motivate a series of changes. The technique creates a collaboration between therapist and patient, such that the latter identifies his or her own reasons for seeking change. Change is then a reflection of the patient’s desires, rather than a goal imposed by the therapist. Although this technique is primarily used in the treatment of addictions, it has also been applied more widely in rehabilitation settings and medical settings, such as in managing diabetes142 and chronic pain.143

Behavior Modification

Behavior modification is the systematic application of the learning principles of classical and operant conditioning122 to alter the frequency and intensity of behavior. Behavior modification has wide application in rehabilitation, including reducing symptoms of PTSD,30 reducing the impact of chronic pain,370 promoting participation in therapies, and enhancing adherence to rehabilitation recommendations.130

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

In cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), patients are taught to identify the impact of thoughts on emotions, and to modify thoughts to achieve relief from emotional distress.86 Introduced by Ellis116 and developed by Beck17 and others, CBT is based on well-replicated research showing that the emotions of individuals are driven more by how they perceive the event than by the event itself. It is also based on the recognition that persons who are depressed, anxious, angry, or hopeless often distort their thinking in ways that create or intensify the emotional upset. With this intervention, patients learn to identify exaggerated or frankly erroneous notions and to replace them with thoughts that are both more realistic and less upsetting. CBT is commonly used in the treatment of depressive disorders and chronic pain syndromes372; it is also being applied to enhance the adjustment of persons having disability within a framework that recognizes disability as a cultural identity.262

Interpersonal Psychotherapy

Built on the work of Sullivan,354 interpersonal psychotherapy391 views psychological problems not as private events but as manifestations of disturbances in social relationships. Consequently the resolution of the problem involves improving relationships and creating more resilient support systems. Given the effects that congenital and acquired disabilities can have on an individual’s family and social network, this therapy framework has many potential applications for rehabilitation populations.

Interventions Targeting Meaning

Psychodynamic

Psychodynamic therapy focuses on the impact that life events have on the way we experience current events, protect ourselves from anxiety, and interact with others. Psychodynamic therapy uncovers factors that help explain why persons might engage in self-defeating behaviors. This therapy is more likely to be used in outpatient settings. Psychodynamic work can help persons make sense of their experience, thus promoting opportunities for informed choices and better self-esteem.

Existential

Existential therapy emphasizes freedom, the option to choose, the courage to be, and the importance of meaning in life.137 Existential therapy creates possibilities for finding meaning in the midst of suffering. Victor Frankl’s work135 on people’s response to life in concentration camps is a poignant example of this approach. Existential therapy is germane to rehabilitation populations because it offers opportunities for freedom and well-being even in the midst of suffering.

Therapies Targeting the Context

Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Dialectical behavior therapy220 focuses on developing interpersonal and emotion regulation skills, while also enhancing distress tolerance and acceptance. Originally developed to aid persons who were suicidal, it has been applied successfully to persons with borderline personality disorders. The concepts, blending active problem-solving techniques with meditative acceptance, are applicable to many painful, chronic disorders.

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

Mindfulness is a way of approaching one’s experience that is based on Buddhist meditation. In mindfulness work, individuals suspend evaluation while becoming more acutely aware of their experience in the moment.190 This mindfulness philosophy has been blended with knowledge of cognitive techniques to create a therapy for the treatment of depression.333 With its intense present focus and suspension of judgment, this therapy can be helpful in opening new ways of seeing one’s experience and might be well suited to the challenges of rehabilitation. This technique would be challenging to implement, however, with persons having certain cognitive impairments.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Acceptance and commitment therapy is an offshoot from the “mindfulness” approach to psychotherapy.165 This therapy teaches a person to accept what cannot be changed, find meaning in it, and then commit oneself to a course of action. Homework exercises support the patient in building and sustaining new skills.

Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Practice

The effectiveness of psychological interventions with several rehabilitation populations has already been evaluated by the Cochrane Library. Conclusions tend to be suggestive rather than certain because the numbers of psychological intervention studies meeting inclusion criteria are small. Also, as noted previously, randomized clinical trials of psychosocial interventions have notable limitations. A body of evidence, however, is accumulating to support the effectiveness of psychological treatments in rehabilitation. Psychological interventions have been shown to be helpful in improving mood and preventing depression after stroke,160 in reducing the emotional distress of patients having incurable cancer,2 in reducing depression and promoting coping among persons having multiple sclerosis,363 in decreasing hypochondriacal symptoms,362 and in reducing anxiety and reducing the likelihood of developing PTSD among individuals with mild-moderate traumatic brain injuries.345

Cognitive Rehabilitation

History of Cognitive Rehabilitation

One could reasonably trace the origin of CR to the 1800s and Broca’s endeavors to improve language functioning of persons with aphasia. After an extended quiescent period, eminent figures such as Goldstein,149 Luria,223 Zangwill,413,414 and Wepman392 developed rehabilitation programs for injured soldiers, deriving tactics from their research findings and models of brain functioning. These programs included a focus on vocational restoration, the sort of “ecologic emphasis” valued by contemporary practitioners. All viewed detailed neuropsychological assessment as a necessary first step in clarifying the nature and extent of impairments to be addressed.31

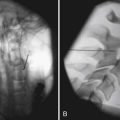

These midcentury efforts inspired little further development until the 1970s, when Ben-Yishay and colleagues27 at the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine, rowing against the prevailing tide of “therapeutic nihilism” (i.e., the view that higher cortical deficits were largely untreatable), devised interventions aimed at specific deficits such as unilateral neglect and constructional impairment. Their methods tended to be what Mateer and Raskin239 described as “direct interventions,” and Kennedy and Turkstra196 called the “train and hope” variety. They were based on the premise that repetitive drill on a discrete function (e.g., visual scanning in cases of neglect) would ameliorate the degree of deficit and also result in improvements in daily life functions dependent on that skill. Meier et al.247 described work based on this perspective, revealing that some success was achieved with this narrowly focused training. For example, patients with unilateral neglect who underwent visual scanning training showed improvements in reading, and those who received training in constructing block designs exhibited improvement in eating behavior (although the connection between the trained skill and the improved function was admittedly tenuous).

Also during the 1970s, Ben-Yishay developed many techniques for treatment of TBI-related deficits in his holistic day treatment program created for Israeli soldiers wounded during the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Developments in CR continued during the 1980s, and the use of computers assumed considerable importance. Clinicians incorporated games such as Pong in attempts to improve sustained attention, capitalizing on the precise control conferred over delivery of training activities and the computers’ capacity to keep track of patient performance.223

As more practitioners entered the CR field, the value of theory-based interventions came to be widely accepted. This development was supported by the emergence of “cognitive neuropsychology,” which featured exquisitely detailed case studies and frequent use of ad hoc testing methods to illuminate the nature of unusual deficits. Its practitioners typically based their work on current theories of neuropsychological functioning in domains such as attention, memory, and executive function. The work of Coltheart et al.76,77 provides a good overview of this perspective, and the case study of a deep dyslexic patient reported by dePartz94 offers a detailed illustration of the derivation of effective treatment strategies from a well-articulated theory of the deficit. Wilson’s volume397 consists of an accessible series of CR case reports, some of which are theoretically based.

A well-known conceptualization of approaches used in CR was offered by Cicerone et al.,72 wherein emphasis was placed on the functional orientation of several strategies, including strengthening or reestablishing previously learned patterns of behavior; establishing new patterns of cognitive activity through compensatory mechanisms (either via neurologic systems or external compensatory mechanisms); and promoting adaption to one’s cognitive disability to improve overall functioning and quality of life. By this definition, CR can target all three levels of functional compromise encompassed by the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Function.405

A detailed enumeration of the multiple potentially efficacious approaches used in CR was offered by Eskes and Barrett.117 They highlighted the following specific CR strategies: (1) retraining of the impaired function; (2) optimization of preserved functions; (3) compensation through substitution of intact skills; (4) utilization of environmental supports or devices to compensate for impaired functions; and (5) training via “vicariation approaches” (which try to recruit related intact brain regions to assume responsibility for functions previously carried out by damaged areas).

The Future of Cognitive Rehabilitation Interventions