Chapter 29 Psychological and physical disorders of the menstrual cycle

PREMENSTRUAL SYNDROME

Premenstrual syndrome (premenstrual dysphoric disorder)

Diagnosis of PMS

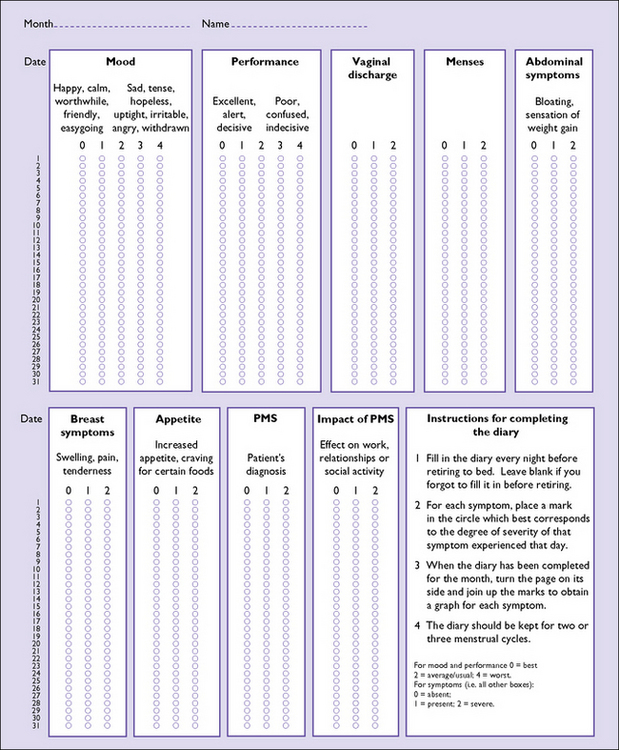

The diagnosis of PMS is made after evaluating the periodicity of the physical and mood symptoms, ascertaining that there is a symptom-free period after menstruation, and ensuring that the symptoms cannot be explained by some other illness. Other illnesses can be exacerbated during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, and this can lead to inaccuracies in the diagnosis. The suspected diagnosis should be confirmed by asking the woman to complete a daily record of symptoms over three menstrual cycles (Fig. 29.1). As well as establishing a firm diagnosis, the value of the daily record is that the woman develops an insight into her symptoms and is encouraged by the fact that the medical practitioner has an interest in her problems.

Aetiology of PMS

The aetiology of PMS is unknown (Box 29.1). It is reported to be more severe if the woman is under stress. There may be a genetic component, but the current theory is that PMS is multifactorial. One underlying abnormality may be a fluctuation in the levels of oestradiol in the luteal phase, which may cause the symptoms directly or by decreasing brain serotonin activity. A problem in accepting this theory is that no consistent fluctuations have been detected with daily monitoring. PMS does not occur if the ovaries are absent.

Box 29.1 PMS summary

| What is PMS? | Negative mood and physical symptoms commencing after ovulation and resolving during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. There must be at least 7 days free of symptoms each month and the symptoms must be of sufficient severity to affect the woman’s lifestyle |

| Aetiology | Unknown |

| Prevalence | All women have cyclical changes in symptoms; 5–15% of women in their 20s and 30s have moderate to severe symptoms |

| Diagnosis | By history and examination, daily diary, and excluding other causes for the symptoms |

| Symptoms |