Chapter 3 Psychogenic Neurologic Deficits

The Neurologists’ Role

Within the framework of this potential oversimplification, neurologists reliably diagnose psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) (see Chapter 10), diplopia and other visual problems (see Chapter 12), and tremors and other movement disorders (see Chapter 18). In addition, they acknowledge the psychogenic aspects of headache (see Chapter 9), pain (see Chapter 14), sexual dysfunction (see Chapter 16), posttraumatic headaches and whiplash injuries (see Chapter 22), and many other neurologic disorders.

Patients often have mixtures of neurologic and psychogenic deficits, disproportionately severe posttraumatic disabilities, and minor neurologic illnesses that preoccupy them. As long as serious, progressive physical illness has been excluded, physicians can consider some symptoms to be chronic illnesses. For example, chronic low back pain can be treated as a “pain syndrome” with empiric combinations of antidepressant medications, analgesics, rehabilitation, and psychotherapy, without expecting either to cure the pain or determine its exact cause (see Chapter 14).

Psychogenic Signs

What general clues prompt a neurologist to suspect a psychogenic disturbance? When a deficit violates the laws of neuroanatomy, neurologists almost always deduce that it has a psychogenic origin. For example, if temperature sensation is preserved but pain perception is “lost,” the deficit is nonanatomic and therefore likely to be psychogenic. Likewise, tunnel vision, which clearly violates these laws, is a classic psychogenic disturbance (see Fig. 12-8). The caveat is that migraine sufferers sometimes experience tunnel vision as an aura (see Chapter 9).

Motor Signs

Deficits that are intermittent also suggest a psychogenic origin. For example, a “give-way” effort, in which the patient offers a brief (several seconds) exertion before returning to an apparent paretic position, indicates an intermittent condition that is probably psychogenic. Similarly, the face–hand test, in which the patient momentarily exerts sufficient strength to deflect her falling hand from hitting her own face (Fig. 3-1), also indicates a psychogenic paresis.

FIGURE 3-1 In the face–hand test, a young woman with psychogenic right hemiparesis inadvertently demonstrates her preserved strength by deflecting her falling “paretic” arm from striking her face as the examiner drops it.

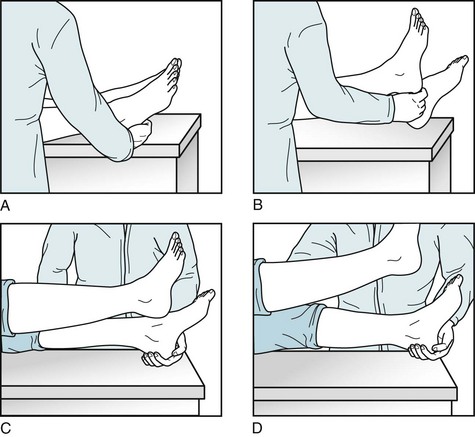

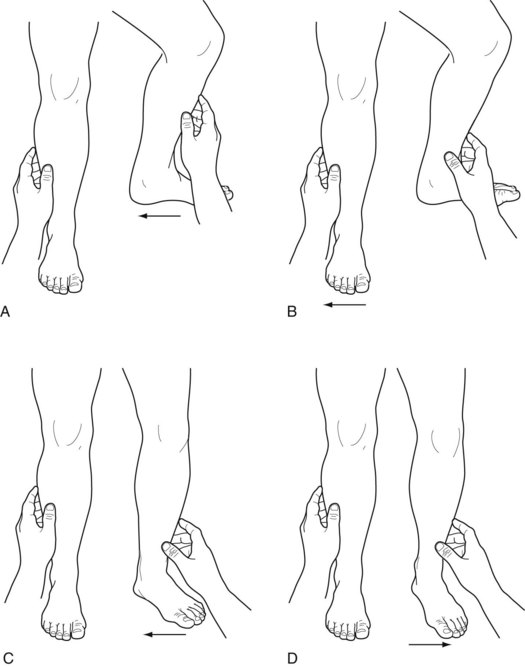

Another indication of unilateral psychogenic leg weakness is Hoover sign (Fig. 3-2). Normally, when someone attempts to raise a genuinely paretic leg, the other leg presses down. The examiner can feel the downward force at the patient’s normal heel and can use the straightened leg, as a lever, to raise the entire leg and lower body. In contrast, Hoover sign consists of the patient unconsciously pressing down with a “paretic” leg when attempting to raise the unaffected leg and failing to press down with the unaffected leg when attempting to raise the “paretic” leg.

FIGURE 3-2 A neurologist demonstrates Hoover sign in a 23-year-old man who has a psychogenic left hemiparesis. A, She asks him to raise his left leg as she holds her hand under his right heel. B, Revealing his lack of effort, the patient exerts so little downward force with his right leg that she easily raises it. C, When she asks him to raise his right leg while cupping his left heel, the patient reveals his intact strength as he unconsciously forces his left “paretic” leg downward. D, As if to carry the example to the extreme, the patient forces his left leg downward with enough force to allow her to use his left leg as a lever to raise his lower torso.

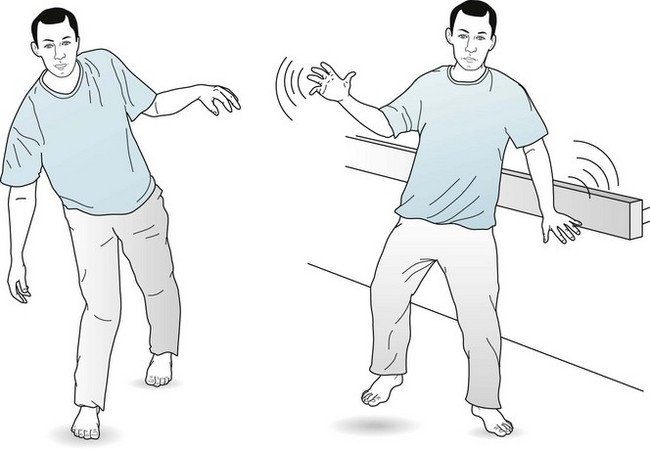

A similar test involves abduction (separating) of the legs. Normally, when asked to abduct one leg, a person reflexively and forcefully abducts both of them. Someone with genuine hemiparesis will abduct the normal leg, but will be unable to abduct the paretic one. In contrast, someone with psychogenic weakness will reflexively abduct the “paretic” leg when abducting the normal leg (abductor sign) (Fig. 3-3).

FIGURE 3-3 Upper series: Left hemiparesis from a stroke with the examiner’s hands pushing the legs together, i.e., adducting them. A, When asked to abduct the left leg, that leg’s weakness cannot resist a physician’s pressure, which moves the leg toward the midline (adducts it). At the same time, the normal right leg reflexively abducts. B, When asked to abduct the normal right leg, it abducts forcefully. The paretic left leg cannot resist the examiner’s pressure, and the examiner pushes the leg inward. Lower series: Psychogenic left hemiparesis. C, When asked to abduct both legs, the left leg fails to resist the examiner’s hand pushing it inward (adducting it). In addition, because of the patient’s failure to abduct the right leg, the examiner’s hand also presses it inward. D, When asked to abduct the normal right leg, the patient complies and abducts it forcefully; however, the left leg, which has psychogenic weakness, reflexively resists the physician’s inward pressure and abducts – the abductor sign.

Gait Impairment

Many psychogenic gait impairments closely mimic neurologic disturbances, such as tremors in the legs, ataxia, or weakness of one or both legs. The most readily identifiable psychogenic gait impairment is astasia-abasia (lack of station, lack of base). In this disturbance, patients stagger, balance momentarily, and appear to be in great danger of falling; however, catching themselves at “the last moment” by grabbing hold of railings, furniture, and even the examiner, they never actually injure themselves (Fig. 3-4).

FIGURE 3-4 A young man demonstrates astasia-abasia by seeming to fall when walking, but catching himself by balancing carefully. He even staggers the width of the room to grasp the rail. He sometimes clutches physicians and pulls them toward himself and then drags them toward the ground. While dramatizing his purported impairment, he actually displays good strength, balance, and coordination.

Another blatant psychogenic gait impairment occurs when patients drag a “weak” leg as though it were a completely lifeless object. In contrast, patients with a true hemiparetic gait swing their paretic leg outward with a circular motion, i.e., “circumduct” their leg (see Fig. 2-4).

Sensory Deficits

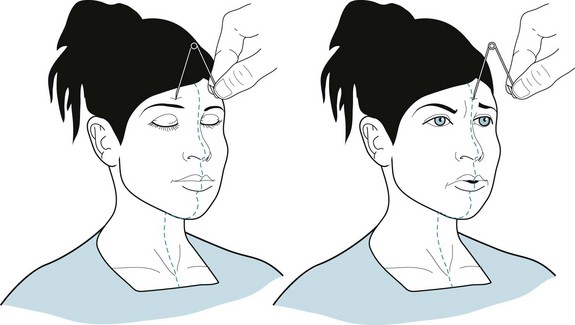

Although the sensory examination is the least reliable portion of the neurologic examination, several sensory abnormalities indicate a psychogenic deficit. For example, loss of sensation to pinprick* that stops abruptly at the middle of the face and body constitutes the classic splitting the midline. This finding suggests a psychogenic loss because the sensory nerve fibers of the skin normally spread across the midline (Fig. 3-5). Likewise, because vibrations naturally spread across bony structures, loss of vibration sensation over half of the forehead, jaw, sternum, or spine strongly suggests a psychogenic disturbance.

FIGURE 3-5 A young woman with psychogenic right hemisensory loss appears not to feel a pinprick until the pin, which is used only for illustrative purposes, reaches the midline of her forehead, face, neck, or sternum (i.e., she splits the midline). When the pin is moved across the midline, she appears to feel a sharp stick.

A similar abnormality is loss of sensation of the entire face but not of the scalp. This pattern is inconsistent with the anatomic distribution of the trigeminal nerve, which innervates the face and scalp anterior to the vertex but not the angle of the jaw (see Fig. 4-11).

A psychogenic sensory loss, as already mentioned, can be a discrepancy between pain and temperature sensations, which are normally carried together by the peripheral nerves and then the lateral spinothalamic tracts. Discrepancy between pain and position sensations in the fingers, in contrast, is indicative of syringomyelia (see Fig. 2-18). In this condition the central fibers of the spinal cord, which carry pain sensation, are ripped apart by the expanding central canal.

Finally, because sensory loss impairs function, patients with genuine sensory loss in their feet or hands cannot perform many tasks if their eyes are closed. Also, those with true sensory loss in both feet – from severe peripheral neuropathy or injury of the spinal cord posterior columns, usually from vitamin B12 deficiency, tabes dorsalis, or MS – tend to fall when standing erect with their eyes shut. In other words, they have Romberg sign (see Chapter 2). By contrast, patients with psychogenic sensory loss can still generally button their shirts, walk short distances, and stand with their feet together with their eyes closed.

Special Senses

When cases of blindness, tunnel vision, diplopia, or other disorders of vision violate the laws of neuroanatomy, which are firmly based on the laws of optics, neurologists diagnose them as psychogenic. Neurologists and ophthalmologists can readily separate psychogenic and neurologic visual disorders (see Chapter 12).

A patient with psychogenic deafness usually responds to unexpected noises or words. Unilateral hearing loss in the ear ipsilateral to a hemiparesis is highly suggestive of a psychogenic etiology because extensive auditory tract synapses in the pons ensure that some tracts reach the upper brainstem and cerebrum despite central nervous system lesions (see Fig. 4-16). If doubts about hearing loss remain, neurologists often request audiometry, brainstem auditory-evoked responses, and other technical procedures.

Patients can genuinely lose the sense of smell (anosmia) from head injury (see Chapter 22), neurodegenerative disorders, or advanced age; however, these patients can usually still perceive noxious volatile chemicals, such as ammonia or alcohol, which irritate the nasal mucosa endings of the trigeminal nerve rather than the olfactory nerve. This distinction is usually unknown to individuals with psychogenic anosmia, who typically claim inability to smell any substance.

Other Conditions

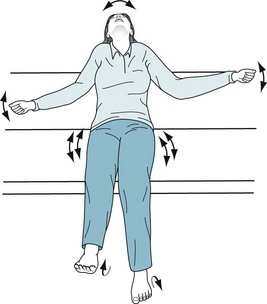

A distinct but common psychogenic disturbance, the hyperventilation syndrome, occurs in people with an underlying anxiety disorder, including panic disorder. It leads to lightheadedness and paresthesias around the mouth, fingers, and toes, and, in severe cases, to carpopedal spasm (Fig. 3-6). Although the disorder seems distinctive, physicians should be cautious before diagnosing it because partial complex seizures and transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) produce similar symptoms.

Potential Pitfalls

Although the neurologic examination itself seems rational and reliable, some findings are potentially misleading. For example, many anxious or “ticklish” individuals, with or without psychogenic hemiparesis, have brisk deep tendon reflexes and extensor plantar reflexes. Another potentially misleading finding is a right hemiparesis unaccompanied by aphasia. In actuality, a stroke might cause this situation if the patient were left-handed, or if the stroke were small and located in the internal capsule or upper brainstem (i.e., a subcortical region). With a suspected psychogenic left hemiparesis, physicians must assure themselves that the problem does not actually represent left-sided inattention or neglect (see Chapter 8).

They also may misdiagnose disorders as psychogenic when a patient has no accompanying objective physical abnormalities. This determination might be faulty in illnesses where objective signs are often transient or subtle, such as MS, partial complex seizures, and small strokes. If given an incomplete history, neurologists may not appreciate certain disorders, such as transient hemiparesis induced by migraines, postictal paresis, or TIAs, or transient mental status aberrations induced by alcohol, medications, or seizures (see Box 9-3).

Possibly the single most common error is failure to recognize MS because its early signs tend to be evanescent, exclusively sensory, or so disparate as to appear to violate several laws of neuroanatomy. Neurologists can usually make the correct diagnosis early and reliably – even in ambiguous cases – with MRIs, visual-evoked response testing, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis (see Chapter 15). On the other hand, trivial sensory or motor symptoms accompanied by normal variations in these highly sensitive tests may lead to false-positive diagnoses of MS.

Neurologists are also prone to err in diagnosing involuntary movement disorders as psychogenic. These disorders, in fact, often have some stigmata of psychogenic illness (see Chapter 2). For example, they can appear bizarre, precipitated or exacerbated by anxiety, or apparently relieved by tricks, such as when walking backwards alleviates a dystonic gait. Also, barbiturate infusions usually temporarily reduce or even abolish involuntary movements. Because laboratory tests are not available for many disorders – chorea, tics, tremors, and focal dystonia – the diagnosis rests on the neurologist’s clinical evaluation. As a general rule, physicians should assume, at least initially, that movement disorders are not psychogenic (see Chapter 18).

Physicians often misdiagnose epilepsy and PNES in both directions (see Chapter 10). In general, episodes of PNES are clonic and unaccompanied by incontinence, tongue biting, or loss of body tone (Fig. 3-7). Furthermore, while exceptions occur, patients tend to regain awareness and have no retrograde amnesia immediately after the movements cease. On the other hand, both frontal lobe seizures and mixtures of epileptic and psychogenic seizures notoriously mimic purely psychogenic ones. EEG-video monitoring during and between episodes is the standard diagnostic test.

FIGURE 3-7 This young woman with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures is screaming during an entire 30-second episode. Several features reveal its nonneurologic nature. In addition to verbalizing throughout the episode rather than only at its onset (as in an epileptic cry), she maintains her body tone, which is required to keep her sitting upright. She has alternating flailing limb movements rather than organized bilateral clonic jerks. She has subtle but suggestive pelvic thrusting.

Baker GA, Hanley JR, Jackson HF, et al. Detecting the faking of amnesia: Performance differences between simulators and patients with memory impairments. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1993;15:668–684.

Eisendrath SJ, McNiel DE. Factitious disorders in civil litigation: Twenty cases illustrating the spectrum of abnormal illness-affirming behavior. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30:391–399.

Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The Spectrum of Factitious Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

Hayes MW, Graham S, Heldorf P, et al. A video review of the diagnosis of psychogenic gait. Move Disord. 1999;14:914–921.

Hurst LC. What was wrong with Anna O? J R Soc Med. 1982;75:129–131.

Hurwitz TA, Prichard JW. Conversion disorder and fMRI. Neurology. 2006;67:1914–1915.

Kanaan RA, Wessely SC. Factitious disorders in neurology: An analysis of reported cases. Psychosomatics. 2010;51:47–51.

Kanaan RA, Armstrong D, Barnes P, et al. In the psychiatrist’s chair: How neurologists understand conversion disorder. Brain. 2009;132:2889–2896.

Letonoff EJ, Williams TR, Sidhu KS. Hysterical paralysis: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. Spine. 2002;27:E441–E445.

Mace CJ, Trimble MR. Ten-year prognosis of conversion disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:282–288.

Richtsmeier AJ. Pitfalls in diagnosis of unexplained symptoms. Psychosomatics. 1984;25:253–255.

Roach ES, Langley RL. Episodic neurological dysfunction due to mass hysteria. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1269–1272.

Roelofs K, Spinhoven P, Sandijck P, et al. The impact of early trauma and recent life-events on symptom severity in patients with conversion disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:508–514.

Sonoo M. Abductor sign: a reliable new sign to detect unilateral non-organic paresis of the lower limb. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:121–125.

Stone J, Carson A. Movement disorders: Psychogenic movement disorders: What do neurologists do? Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:415–416.

Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, et al. La belle indifference in conversion symptoms and hysteria: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:204–209.

Stone J, Warlow C, Sharpe M. The symptom of functional weakness: A controlled study of 107 patients. Brain. 2010;133:1537–1551.

Teasell RW, Shapiro AP. Misdiagnosis of conversion disorders. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:236–240.

Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74:223–228.